Chapter 11

Time

Expanding upon his experiences visiting the Ohioan mounds, Newman disconnected presence from “space and its manipulations.” The sensation of presence, he insisted, “is the sensation of time—and all other multiple feelings vanish like the outside landscape. . . . Only time can be felt in private. Space is a common property. Only time is personal, a private experience. That’s what makes it so personal, so important. Each person must feel it for himself. . . . The concern with space bores me. I insist on my experiences of sensations in time—not the sense of time but the physical sensation of time.”1 In a draft for the same statement, Newman wrote, “The greatest, most profound feelings of the human spirit never arise inside a frame of space. They always arise around the concept of time.”2

What did Newman mean by physical sensations of time? There is no way to know for certain, but in another compelling correspondence, Heidegger also argued in his magnum opus that the meaning of Being was time. Presence does not simply signal spatial here-ness (e.g., “I was present at the meeting”); it is also a state of Being in the chronological present. As Heidegger put it, we gain our “understanding of being from ‘time.’ . . . Beings are grasped in their being as ‘presence’; that is to say, they are understood with regard to a definite mode of time, the present.”3 Presence, then, is as much a question of time as bearing and self-awareness; inasmuch as Newman saw time as private, so did Heidegger. Having claimed the meaning of Da-sein to be one’s own,4 Heidegger also qualifies time as individual and private, not as public or objective. Half an hour, he writes, “is not thirty minutes, but a duration which does not have any ‘length’ in the sense of a quantitative stretch. . . . An ‘objectively’ long path can be shorter than an ‘objectively’ much shorter path which is perhaps an ‘onerous one’ and strikes us as infinitely long.”5 As already indicated, Heidegger’s interest in boredom also underscores how connected to physical sensations our descriptors of time actually are (the way the German word for boredom, Langeweile, literally means “long while”). What is “decisive about reckoning with time,” Heidegger concludes, is not “the quantification of time, but must be more primordially conceived in terms of the temporality of Da-sein reckoning with time. ‘Public time’ turns out to be the time ‘in which’ innerwordly things at hand and objectively present are encountered. This requires that we call these things unlike Da-sein within-time.”6 Da-sein, then, exists within time differently than what is not Da-sein; Da-sein experiences time independently of quantifiable constraints.

Unlike animals or inanimate objects, human beings exist in the present, with the past, and in anticipation of the future. As Newman would say, these experiences are personal and private, betraying Being’s inextricable connection to time. In German, moreover, references to time are profoundly physical in nature, establishing another potential link with Newman’s avowed interest in physical sensations of time. Future (Zukunft), as Steiner explains, means “that which comes toward one.” Anticipating the future, Da-sein is constantly “ahead of itself.” Present (Gegenwart) Heidegger “hyphenates as Gegen-wart and interprets as meaning a ‘waiting-towards’ or ‘waiting-against,’ with ‘against’ signifying . . . ‘in the neighborhood of,’ ‘in proximity to.’ ‘Present-ness’ is ‘a way of being-alongside.’”7 This terminology—again—is emblematic of how time may be described, metaphorically, by physical experiences. The past is behind you; the future ahead of you; and the present is where you are located at this moment.8 Da-sein, Heidegger writes, “exists, so to speak, ‘forward’ and leaves everything that has been ‘behind.’”9 Even our everyday expressions reveal how readily we conceptualize time and space as if they were interchangeable: remembering is “looking backward,” anticipating is “looking forward,” and when we are told to “look here,” we pay attention to what is being expressed now. We also speak of a “near future” or a “distant past.” When asked how far Boston is from New York, we can answer “three and a half hours” just as easily as “approximately two hundred miles.”10 It has been found, moreover, that the degree of precision with which languages express space and time is internally consistent (i.e., languages that tend to be precise or imprecise with one are the same with the other).11 And many of the linguistic prepositions and descriptors we employ to designate space are readily applicable to time. In English, for instance, we have such expressions as the following: he came “on time,” “around midnight,” “at the top of the hour,” “in July,” “in the middle of the week,” “under an hour,” “over the allotted time,” “within a minute,” “inside of a minute,” and so forth. We can “have our down time” or “take time off,” and be “ahead,” “behind schedule,” or even “in the nick of time.” Not surprisingly, the biologist John O’Keefe speculates that temporal prepositions “are similar to (diachronically borrowed from?) their homophonic spatial counterparts.”12

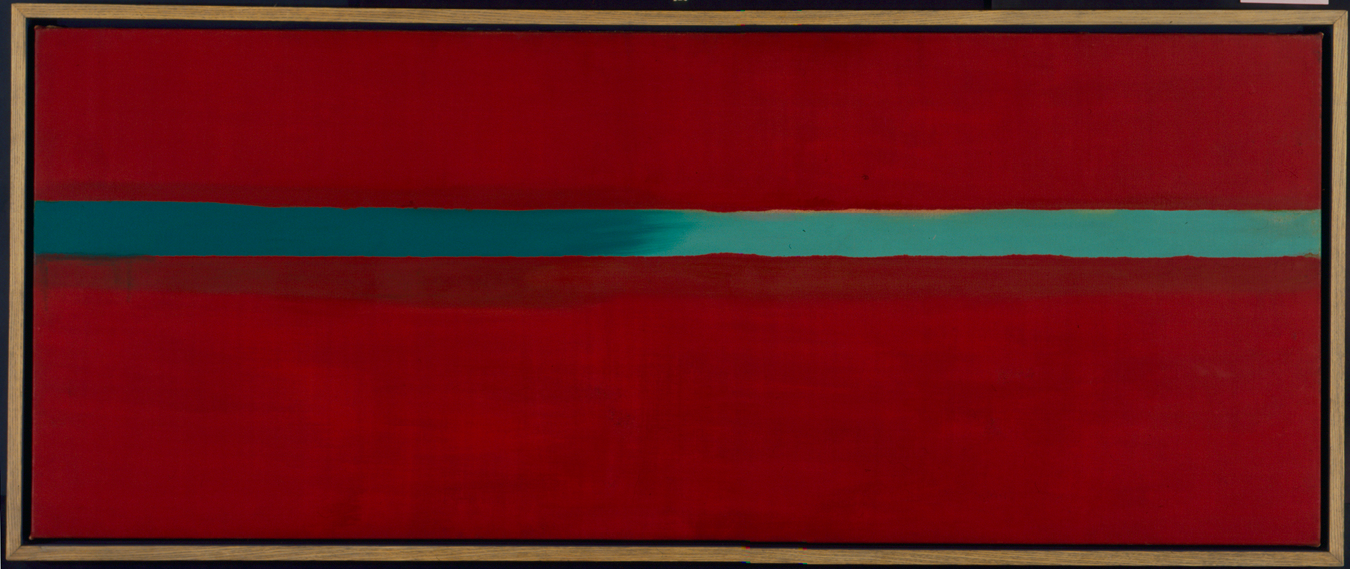

Accordingly, if Newman utilized the expanses of his canvases to evoke, not just space (the “hereness” versus “thereness” of experience), but also the idea of time (the ways in which past and future encroach upon us), then the space/time parallel squares with Heidegger’s view that Da-sein is both temporal and spatial.13 The two concepts are inextricable; the “being-there of our own Dasein,” Heidegger explains, “is what is precisely and only in its temporally particular ‘there,’ its being ‘there’ for a while.”14 Revealingly, Heidegger refers to time as a horizon, a suggestive metaphor, not simply because of its spatial character, but also because this trope is echoed in Newman’s statement: “For me space is where I can feel all four horizons, not just the horizon in front of me and in back of me.”15 The feeling of space created by his paintings, he added, should make a spectator feel “full and alive in a spatial dome of 180 degrees going in all four directions.”16 Newman even titled one of his works Horizon Light (figure 11.1). Whether he employed “horizon” to refer to time is impossible to say, but if he were thinking along Heideggerian lines, he would have appreciated the philosopher’s view that the “perspective in which Dasein constantly moves . . . proceeds to distribute itself into present, having-been, and future. These three perspectives are not lined up alongside one another, but originarily simply united in the horizon of time as such.”17 “The temporality of Dasein,” Brock explains, “with its relations to future, past, and present . . . opens up the ‘horizon’ for the question about ‘Being.’”18

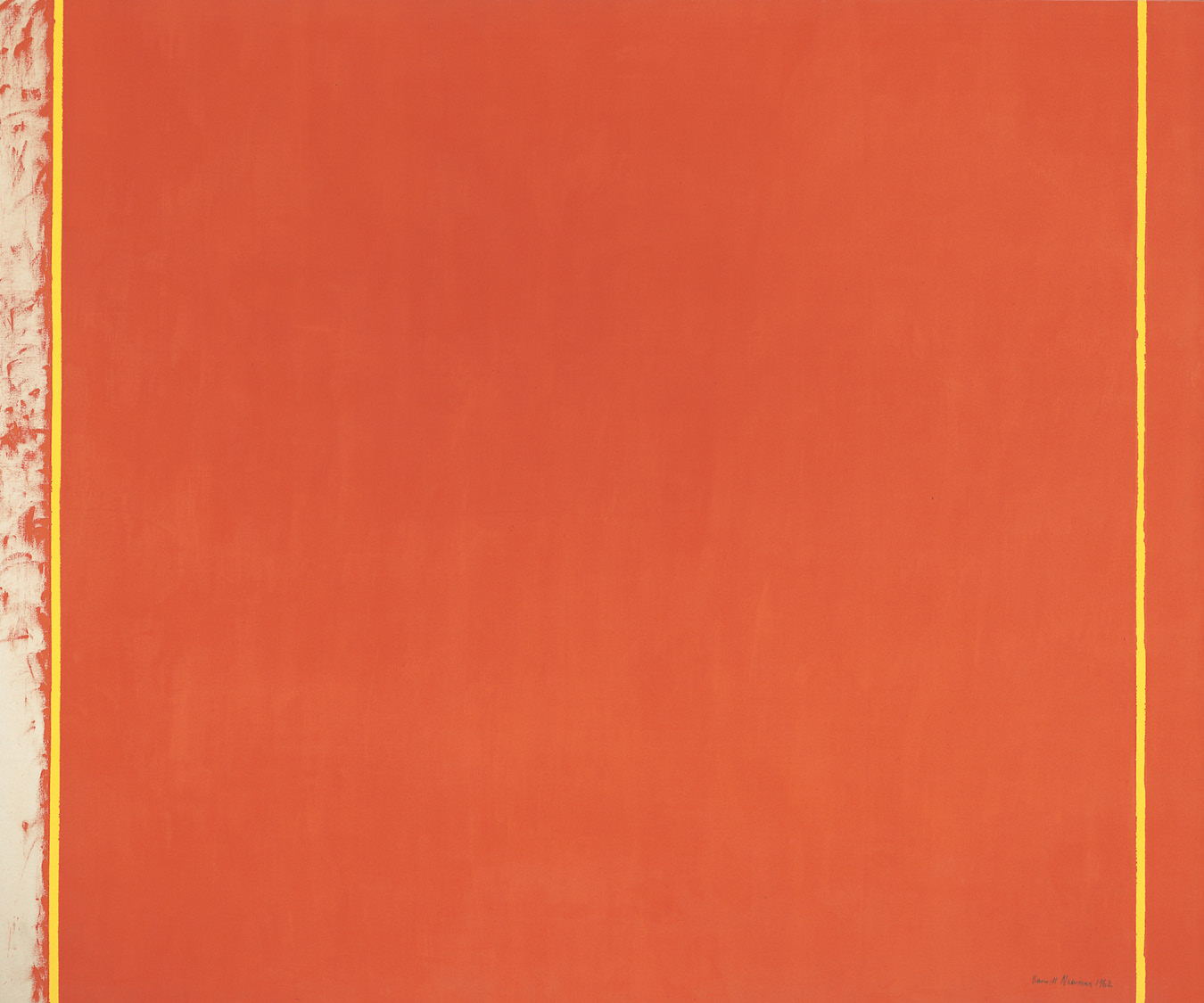

Figure 11.1. Barnett Newman, Horizon Light (1949), oil on canvas, 30.5 3 72.5 inches. Sheldon Memorial Art Gallery, University of Nebraska at Lincoln. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Thomas Sills © 2012 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

It was speculated in a previous section that multiple zips in Newman’s paintings represent the relationship between discrete individual human presences (recall that Newman hoped his art would remind his spectators of their own “totality” and “separateness” as well as their “connection to others” who “are also separate”). But given Newman’s intent to devise visual analogs for physical sensations of time, the zips might also represent the same individual presence at different moments in time. One says “at different moments,” but this designation is still too literal. More Heideggerian would be to understand multiple zips as evoking the way memory throws us back toward our past, or how anticipation projects us toward the future. Bois has already described the effect of lateral expansion created by Newman’s canvases and the need for spectators to rely on their peripheral vision to experience the artist’s work.19 Compellingly, Peter De Bolla also wrote of the zips animating “the canvas, introduc[ing] time to the look, and help[ing] temporalize the experience of viewing.” “In effect,” De Bolla, writes, “the zips keep time.”20 In parallel, one may propose that, standing, say, at the center of a painting punctuated by stripes on the left and right, we might tend—given that, in the West, we have a propensity to read a painting from left to right—to see the stripes to our left as “behind” and those to our right as “ahead.” This reinforces Bois’s suggestion that, when perusing a Newman, our gaze is not just frontal, but lateral, that we peruse not just the stripes, but scan the entire canvas.21 If we construe time as Heidegger does, in terms of a horizon, then “behind” will mean “past” and “ahead” will mean “future.” And the ways in which we reflect on our past and our future, in many ways, will also determine how we are, our state of Being, in the present.

As already noted above, Heidegger describes the spatiality of Da-sein as having “directionality,”22 just as, for William James, our experience of time is analogous to standing on a ship with a bow and a stern, “a rearward- and forward-looking end.”23 Could this be what Newman meant when he spoke of physical sensations of time? Of course, there is no way to know, but since Newman was no less concerned with the self, with human presence, and with the quandary of existence, then it is significant to mention Heidegger’s view that broaching the question of Being opens Da-sein “to unasked possibilities, futures, and at the same time binds it back to its past beginning, so sharpening it and giving it weight in its present. In this questioning our being-there [Da-sein] is summoned to its history in the full sense of the word.”24

But time is a tricky dimension. Even if it bestows meaning to our existence, we have difficulty accurately gauging its passage. Even professional athletes and professors, who engage in the same activity week after week, need to be reminded of how much time is left on the shot clock, or must glance at their watches to know when the bell will ring. “We experience time,” Stefan Klein writes, “exclusively against the backdrop of events.”25 Accordingly, one might construe the beams along a Newman canvas as designating important moments in the stream of time, their select placement at specific points eliciting different responses depending on the spectator’s perspective. Importantly, Mark Johnson and George Lakoff have identified the various ways verbal expressions betray our relationship with time,26 some of which may be directly relevant to interpreting Newman. In what they call the time-as-moving-object metaphor, observers feel as though they stand immobile in the present with the past moving behind and the future approaching ahead of them, a concept exemplified in expressions such as “time flies when you’re having fun,” “he finally put this experience behind him,” or “I don’t know where the time has gone.” But it is also possible to conceive of time-as-stationary, with the observer moving through its continuum, exemplified in expressions such as “we just passed the deadline,” “we’re halfway through the holidays,” or “we’re coming to the end of game.” These distinctions are based on our own physical experience: we can describe a room from a stationary position (a “gaze tour”) or as if we were literally moving through it (a “walking tour”).27 To this classification, Lera Boroditsky contributes the distinction between time-as-procession and time-as-landscape, which works in concert with Lakoff and Johnson’s categories.28 In the idea of time-as-procession, the evaluation is egocentric insofar as observers use themselves as the main, stationary reference point by which time figuratively passes. In the time-as-landscape metaphor, by contrast, the reference points are established by time itself, in whose dimension we are continuously moving. Although we often use both modes to refer to time, the two are actually incongruent. We can say “I am getting used to this as time goes by” (time-as-moving-object) or “we’ll cross that bridge when we get to it” (time-as-landscape), but we cannot say “we’ll cross that bridge as time goes by.” These modes of conceptualizing time are mutually exclusive, most likely because they hinge on completely different physical experiences to communicate their point.

Newman, arguably, availed himself of both alternatives, though, given their incongruence, not in the same paintings. Smaller pieces with symmetrical compositions, Onement I (figure 2.1), for instance, will encourage the spectator to stand relatively motionless at their very center. The viewer will tend to take him- or herself as a frame of reference, mirrored by the frame of reference provided by the painting: the left of the painting is also to our left. The viewer-centered frame of reference thus coincides with the object-centered frame of reference, in which case, the central stripe, consistent with the time-as-moving-object metaphor, will stand for the present, with the left and right halves of the painting as the past and future, respectively. That time can be mapped onto space in this way should hardly be surprising; Bernard Comrie posits that such a diagrammatic representation also underpins—conceptually—the employment of past and future tenses in language, thus drawing yet another connection between language and space.29 On this account, canvases such as Onement or Be, by virtue of the beam’s central placement, and their strict adherence to bilateral symmetry, compel us to focus on the center as a visual analog for the “now,” a scenario consistent with the time-as-moving-object or time-as-procession metaphor.

In real-life situations, however, the temporal present is a difficult sensation to appreciate. If asked to concentrate exclusively on the “now,” our minds will soon wander, remembering something yesterday or planning for something tomorrow.30 Newman provided analogs for such experiences as well. Larger paintings with multiple stripes, Vir Heroicus Sublimis (figure 6.7) for instance, encourage the spectator to stand at different points before the picture surface, not simply because the scale of the piece challenges any attempt to grasp it in its entirety,31 but also because the center, normally the ideal position from which to peruse a work of art, is bereft of any incident. Confronted with this void, the spectator will tend to wander, most likely stopping longer before each of the beams than before empty space, injecting discrepancies between our individual, viewer-centered frame of reference and the intrinsic, object-centered frame of reference of the canvas (just as we have trouble fixating our attention on the temporal present and are irresistibly drawn to remember the past or anticipate the future). The spectator’s need to move, then, could be interpreted as an analog to the difficulty we experience living in the moment, concentrating on the now—a scenario more consistent with the time-as-landscape than the time-as-moving-object metaphor.

It needs mentioning, equally, that, even if Newman left the center of a composition bare, prompting observers to attend to the stripes at either side, that same center will still exert a certain pull, if only because the idea of “the present,” even if it cannot hold our attention consistently, supplies the only point around which “the past” and “the future” can be apprehended. “No language,” Steven Pinker writes, “has a tense that refers to the entirety of time other than the ‘now.’” This means that the now “intrudes between the past and the future with no detour around it, ineluctably dividing time into two noncontiguous regions.”32 This is not to suggest, of course, that arbitrary events cannot be inserted into the stream of time. In the West, the birth of Christ marks the time before and after the “Common Era,” and, in our own individual lives, special occasions establish chronological frames of references: births, graduations, weddings, retirements, and so forth. And since we construe remembering as a sending, and anticipation as a projection, a canvas with two beams at the left and right of an empty center could thus correspond to a sentence such as “between recruitment and retirement I plan to do the following,” when persons, still employed, are looking back to their date of hire and forward to their farewell party. But even in such cases, past or future, though they function as quasi-autonomous reference points, are always triangulated against a perpetual present: just as “left” and “right” would be meaningless without a concept of “center,” “before” and “after” are no less so without the “now.” Analogously, if an empty central area invites us to peruse any stripes Newman placed at its periphery, we will retain cognizance of the intrinsic center of the canvas no less than of our relationship to the beams distant from us at any given moment. Those on the left will be read as belonging to the past, those on the right to the future, and our moving along (or even scanning) the painting laterally as somehow equivalent to moving through the stream of time, with the middlemost void as a recalcitrant but conceptual demarcation point around which no deviation is possible.

Though reflected in our figures of speech, the sense of moving through time as through a landscape violates an undeniable aspect of our experience: namely, that time is irreversibly uni-directional. The illusory sense of motion supplied by memory and anticipation, however, brings us back, conveniently, to Heidegger, a philosopher whose concept of time is closely anchored to that of history. If Da-sein’s ability to speak allows it to question its own existence, that same ability permits Da-sein to understand its relationship to time and “live with its past.” Through culture, human beings inherit customs and traditions; by means of language, they record their history and ponder its significance; in thinking, they plan for and anticipate upcoming events. By establishing a relationship with time, Da-sein, unlike everything else in the world, becomes historical, and recognizes how time bestows meaning upon Being. “Having time,” therefore, does not mean having the time to go to work and run errands; it means that living within this dimension offers opportunities. Whether completely open, or established in advance by destiny, the meaning of Being resides in our future. Just as Newman was reluctant to explain his art independently of an individual spectator’s act of looking, and himself required long periods of contemplation in order to determine the emotional resonance of specific works, Heidegger refrained from defining the specific meaning conferred by time. That meaning resides in the unwritten potential we have yet to fulfill in the future; it is incumbent upon us to fulfill this potential in a manner that is genuine and authentic, not one imposed upon us by others. This is the responsibility that the future, by still lying ahead of us, asks us to assume.

Not surprisingly, Heidegger saw authentic existence in terms of “anticipatory resoluteness.”33 Anticipatory resoluteness is “the being toward one’s ownmost, eminent potentiality-of-being.”34 In other words, we must resolve to maintain our autonomy, face the terror of existence, and fulfill the potential afforded by future possibilities. The “letting-come-toward-itself that perdures the eminent possibility,” according to Heidegger, “is the primordial phenomenon of the future.”35 Anticipation, he continues, makes Da-sein futural in an authentic way, allowing Da-sein to come toward itself and be futural in its Being.36 As Heidegger employs space metaphorically, his terminology—referring to time as a horizon, or to Da-sein as coming toward itself—could easily have been construed by Newman as “physical representations of time,” albeit in an existential rather than exclusively chronological sense: any beams located to the spectator’s right might thus signify a future self, an unfulfilled potential coming toward us as a definite possibility. The prospect of seeing time as an existential dimension also reinforces Newman’s insistence that time is an individual rather than collective property. Since time is an immaterial dimension, we have no choice but to describe its passage by resorting to spatial metaphors. Heidegger concurred: when time is described as “long” or “short,” or as a line between two points, these terms are extrapolated “from the representation of three–dimensional space.”37 But precisely because this method of reckoning with time is metaphorical, it is potentially deceptive, particularly as Heidegger, somewhat predictably, sees time within an authentic/inauthentic framework. Only authentic time—which encourages us to ponder the full relations between past, present, and future, and opens us toward our possibilities—has true dimensionality. Authentic time is “the mutual reaching out and opening up of future, past, and present.” Dimensionality, Heidegger writes, “belongs to true time and to it alone.”38 Only true time, for Heidegger, is “three-dimensional.”39

Not comprised of quantitative increments (days, months, years), “true” time is an existential dimension that unfurls when we accept the responsibilities we inherit from the past and assume a resolute stance toward our potentiality-for-being in the future. It is in this sense that authentic time is three-dimensional. Inauthentic time, however (i.e., the time that is frittered away doing everyday chores), is uni-dimensional and unsusceptible to ignite deeper understanding. Did this idea motivate Newman to evoke “physical sensations of time,” to make spectators feel inside “a spatial dome going in all four directions,” or “alive in the sensation of complete space?” Even if this question cannot be answered with certainty, these declarations accord with Heidegger’s view that a linear progression from point to point evokes a false, uni-directional sense of time, while a broader, more open dimensionality evokes authentic time’s multi-perspective of past, present, and future. In fact, while discussing Aristotle’s concept of time, Heidegger used an image very similar to Newman’s dome-like vaults: “everything that is, is in time; but everything that exists is also inside the revolving vault of heaven, which is the outermost limit of all being. Time and the outermost heavenly sphere are identical.”40

Along these lines, analogies between space and time encourage parallel analogies between the employment of time and the employment of space. Expressions such as “losing time,” “quality time,” or “time is money,” reflect how readily we think of time as a resource, as something capable of being spent, wasted, or even lost. And since time is exploitable no less than natural resources, Heidegger hoped to counter this tendency by re-conceptualizing several Greek terms. By translating chreon as “usage” rather than “necessity,” a fundamental aspect of its meaning comes into view: not usage in the conventional sense of employment and manipulation, but in the more profound sense of enjoyment—being “pleased with something and so to have it in use.”41 Just as we must heed nature to preserve it, we must also heed time to enjoy what it offers, not turn it into standing reserve by forcing ourselves to be as efficient as possible. Availing ourselves of time permits us to ask important questions, not to rush about madly from activity to activity. “Used” in this way, time gives meaning to Being, mainly because Heidegger employs the term “use” to signify letting “something present come to presence as such . . . to brook, to use . . . to hand something over to its own essence.”42 If we “use” time authentically, we allow the truth of time to become manifest, reinforcing Heidegger’s connection between presence and truth. Presence is also related to time (and, possibly, to Newman’s “physical sensations of time”) because usage delivers what is present “to its lingering.”43 Human beings, as well as all that exists, exist only for a while, and it is usage in the Heideggerian sense that establishes the borders of this “while,” permitting beings to come into presence and then fade into obscurity when their allotted time expires.44 As existence comes into presence within the dimension of time, this time, perforce, is limited. Time allows us to exist and come into Being only within strictly defined boundaries; the “while” into which we have been delivered, Heidegger writes, “bounds and confines what is present.” “That which lingers awhile in presence . . . comes to presence within bounds.”45

Could this correspond to Newman’s worldview as well? Since the differentiation between the stripes and their backgrounds denotes the human presence’s totality and separateness—its “coming to presence within bounds” in Heideggerian parlance—then the human presence’s physical boundaries—given Newman’s insistence on physical sensations of time—also denote our coming into presence within the dimension of time. If our physical extension is limited by the literal boundaries of our own bodies (e.g., we exist “inside” not “outside” our bodies), our existence is also limited by our chronological lifespan (another physical boundary, as it were). All of this may or may not account for Newman’s cryptic statement about physical sensations of time, but if this ambition went hand in hand with his desire to trigger spectators’ awareness of their own presence, then it stands to reason that presence and time are related—that a sense of one’s own presence also entails an awareness of where one is now, at this present moment, as well as how this moment is affected by remembering the past and anticipating the future. Hence, although Da-sein is aware of its own spatial/existential location in the world, that awareness is inextricable from its awareness of being released, not only into a “there,” but also within a “while,” which, like the “there,” also has boundaries that are coexistent with our physical existence (our time) on earth. In view of the ease with which we construct equivalences between space and time, it is hardly surprising that Heidegger spoke of “temporal space,”46 an image no less physical than the expression “time horizon.” And though there is no guarantee that Newman was thinking along parallel lines, his “physical sensations of time” dovetail nicely with Heidegger’s “temporal space.”

For Heidegger, time is the very first dimension, without which human beings, by virtue of existing “in” it, could not even experience space. Steven Pinker came at the issue another way, conceding that, however horrendous a prospect, one can imagine oneself blind and paralyzed, deprived of space; yet to imagine oneself existing outside of time, frozen as it were, is inconceivable.47 A stone, Heidegger would add, exists in space, but, having no cognizance of time, a stone exists in space without experiencing it. Animals do experience time, but, having no sense of a historical past and potential future, they do so to a far poorer extent than human beings. By dint of having language and being historical, human beings experience time in its full dimensionality, allowing them to have a sense of place and a full appreciation of their position in the world. “For true time itself,” Heidegger writes, “is the prespatial region which first gives any possible ‘where.’”48 Having a sense of place thus presupposes an awareness of time. When Newman described feeling his own presence in Ohio, that kind of experience is only accessible to a historical being—a being like Da-sein.

Our sense of presence and place, however, induces an additional form of awareness: inasmuch as being “here” makes us cognizant of not being anywhere else, an awareness of the full dimensionality of past, present, and future underscores the brevity of time. If “usage” means allowing what is present to come into presence, usage also establishes the “boundaries of the while to whatever lingers awhile in presence.”49 In other words, by virtue of coming into presence, whatever is present is confined to the chronological while into which it is allowed to linger. By marking the beginning and end of our existence, birth and death thus demarcate the limits of “our” individual time—an additional way of interpreting what Newman may have meant by physical sensations of time. And when the artist ascribed, instructively, the title The Moment (figure 2.5) to one of his paintings, it was, ostensibly, because the spatial sensations sparked by the painting suggested, at least to him, a physical “equivalent” to a transient but distinct “instant” in time (no differently than the way time lines also demarcate chronological distinctions by means of spatial columns or stratifications). In its intensity, the yellow band stands out dramatically against the darker, more gestural areas surrounding it—again evoking something coming into presence within bounds. The clarity with which the yellow area is defined and segregated also suggests that the moment is of special import. Against the vertical strokes behind it, the beam almost looks as if it were expanding laterally, exacerbating its intensity. As was already mentioned, Newman once related that, during the creative act, he felt “present at a moment which is very real [italics mine].”50 It is the “reality” of this “moment” that the stark color contrasts and spatial differentiations convey: the moment is short-lasting yet intense; it has a beginning and an end, like any physical entity.

To counter the average experience of time, Heidegger also used the idea of an intense “Moment” to articulate authentic temporality: “Resolute, Da-sein has brought itself back out of falling prey in order to be all the more authentically ‘There’ for the disclosed situation in the ‘Moment.’”51 By contrast, the inauthentic experience of time is a “pure succession of nows, without beginning and without end, in which the ecstatic character of primordial temporality is leveled down.”52 When ensnared in the they, we live in a dull and mundane manner, without moments of great intensity, during which time seems infinite but homogeneous. The they understands time as an endless continuum, a continuum where, in the end, time is always available to take care of everyday responsibilities. The infinity particular to inauthentic time, Heidegger interjects, reveals the “negative character of temporality.”53 The authentic concept of time, on the other hand, induces cognizance of the mortality (and eventual impossibility) of Da-sein: that, at some point, all of our possibilities will be closed off—permanently.54 Although time goes on, primordial time is finite.55 The distinction is critical because, adopting an inauthentic understanding of time, we will attend exclusively to everyday activities, forcing Da-sein into a state of dispersion.56 “Tangled up in itself, the dispersed not-staying turns into the inability to stay at all. . . . In this inability Da-sein is everywhere and nowhere.”57 The Heideggerian Moment is precisely the opposite; dispersion is nullified, resolution is found, and Da-sein is brought back to itself: “‘In the Moment’ nothing can happen.”58 “Just as the person who exists inauthentically constantly loses time and never ‘has’ any, it is the distinction of the temporality of authentic existence that in resoluteness it never loses time and ‘always has time.’ For the temporality of resoluteness has, in regard to its present, the nature of the Moment.”59

Understanding time inauthentically, we are dispersed; we rush about madly; we never have time to take care of everyday duties; we are also beguiled into thinking that, in the future, time will always be available. Understanding time authentically, we accept the end of our existence, a realization that brings us back to ourselves from countless distractions, and allots us the time necessary to reflect meaningfully on our situation in the “Moment.” This reading dovetails nicely with aforementioned interpretations of the symmetrical Moment (figure 2.5) versus the asymmetrical L’Errance (figure 7.1). When we come into presence, we recognize authentic time and the strict bounds into which our existence has been delivered: at this moment, the time we have, however limited, becomes all the more real and meaningful. We are wrested from entangled dispersion and are brought back to ourselves (Heidegger) or we are given a sense of place, and understand our individuality and our separateness (Newman). This is what, conceivably, Newman and Heidegger both meant by the “Moment.” Just as Heidegger stressed Da-sein’s coming back to itself, Newman insisted that his paintings were executed “in utmost solitude,” and should be examined “in relation to the true nature and degree of how much solitude.”60 From this perspective, Newman’s concerns with presence, place, and with physical sensations of time are intimately related. It is the stillness of a “Moment” à la Heidegger that Newman, arguably, sought to convey in his canvases, with vertical zips arresting our natural proclivity to read a painting from left to right, compelling us to ponder, for a short stretch of time, the separateness of our own Da-sein, a “Moment” when, as the philosopher would put it, “nothing happens,” or, more accurately, when nothing distracts us from the reality of our existential predicament.61

In a way, when “nothing happens,” everything important happens. In a “Moment” when no mundane activity or rushing about occurs, as in L’Errance, Da-sein becomes present in the chronological as well as existential sense. Of course, we also acquire a sense of place or become resolved while exercising our language faculty: when we employ those performatives previously discussed. In nominating, promising, or commanding, we affirm our Da-sein and our place in the world. Instructively, Bernard Comrie observed that situations rarely “coincide exactly with the present moment . . . [or] occupy, literally or in terms of our conception of the situation, a single point in time which is exactly commensurate with the present moment.” Yet, among examples of such situations, Comrie includes performative sentences: promises or acts of naming. Although these acts are not exactly synchronous, “since it takes a certain period of time to utter even the shortest sentence, they can be conceptualized as momentaneous, especially in so far as the time occupied by the report is exactly the same as the time occupied by the act, i.e. at each point in the utterance of the sentence there is coincidence between the present moment with regard to the utterance.”62 This account provides a framework wherein Newman’s and Heidegger’s Moment takes concrete form: something “happens” at the very moment we name, promise, or command because the resolution, authority, and standing of our Da-sein is directly implicated.

Heidegger’s insistence—that, during the Moment, the “authentic, historical constancy of the self”63 comes forth—also recalls Newman’s—that the “self, terrible and constant,” was, for him, the subject matter of painting. Newman may have been insinuating that the “self” he was evoking in his paintings was cognizant, resolute, and unified in the face of mortality. In parallel, cognitive psychologists argue that, when the mind conceptualizes an entity in a location, it tends “to ignore the internal geometry of the object and treat it as a dimensionless point or featureless blob.”64 This may account for the strict simplicity and indivisibility of Newman’s beams. Internal features and detail are downplayed, but the stark verticality recalls a marker or flagpole: a demarcation, a border, or a claim of property. As such, these poles communicate a sense of permanence and resilience in the face of whatever surrounds them—quite unlike the sensation of dispersion Heidegger associates with inauthenticity. Not surprisingly, the philosopher refers to everyday, factual life as “ruinant experience,” a term extrapolated from ruin or ruinous, which he also describes as “non-presence,”65 the diametrical opposite of “authenticity.” Again, Newman’s statement about man being sublime only insofar as he is aware comes to mind, as well as his view that the modern artist succeeded in setting “down the ordered truth that is the expression of his attitude towards the mystery of life and death.”66

Death, of course, is central to any authentic understanding of time, precisely because accepting our finitude compels us to confront that most momentous and unavoidable of events. If art is made in extreme solitude for Newman, death, for Heidegger, is that one aspect of existence we experience alone, that we cannot give over to others, and that we encounter in complete isolation. Death is also something we face either authentically or inauthentically. We may delude ourselves into thinking that death can always be deferred and therefore of no concern to us “now.” Or we can grasp how finitude accentuates the intensity of Da-sein and accept the certainty of our no longer Being. When faced with the inevitability of mortality, with the inescapable prospect of finitude, we are wrested away from the inauthenticity of public time—from thinking of time as infinitely extendable—and achieve genuine understanding.

As already intimated, authentic understanding reveals time as future possibility. For Heidegger, inauthenticity belongs to actuality, authenticity to possibility.67 Though he recognizes both modes as inescapable (we could no more envision the possible without understanding the actual, than the actual without envisioning the possible), there is no question that, between both, Heidegger prioritizes the possible. And because the meaning of existence remains a cardinal question of his philosophy, that meaning is primarily understood in terms of humanity’s potential. Analogously, we might read the minimal austerity of Newman’s beams as intimating that, even if Da-sein may appear as it is, undisclosed and transparent in its truth, it can never appear as all that it is.68 As bare and exposed as they are, Newman’s beams underscore how, in its present state, Da-sein is always incomplete—in a state of “lack” or “absence.” The flip side, ironically enough, is that, however laconic and recalcitrant, or ostensibly bereft of meaning, the zip is meant to embody an excess or overabundance of meaning: namely, all of the future possibilities a Da-sein may project and yet realize in the future. Until its death, after all, Da-sein remains what Heidegger likes to call a “not-yet,” something that has not realized all of its potential. Da-sein, in effect, must interpret itself and, in the process, transcend, even overreach, its ontic limitations.69 Since Da-sein always exceeds its own factual existence, its meaning is its own possibility, a possibility to which it must lay claim. That is why the philosopher prioritizes the possible over the actual, and views a confrontation with death—its imposition of a limit to existence—as a fostering of authenticity.

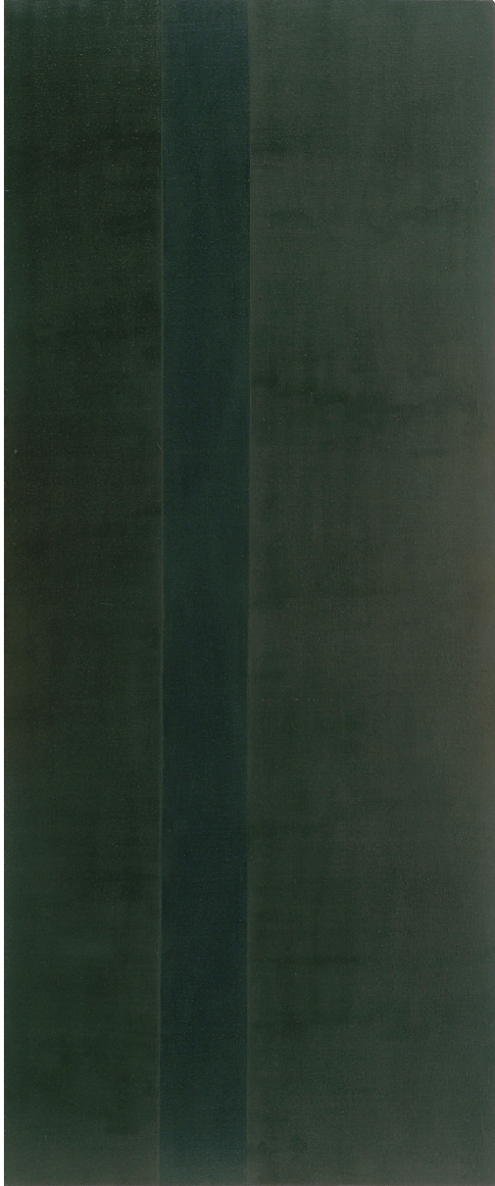

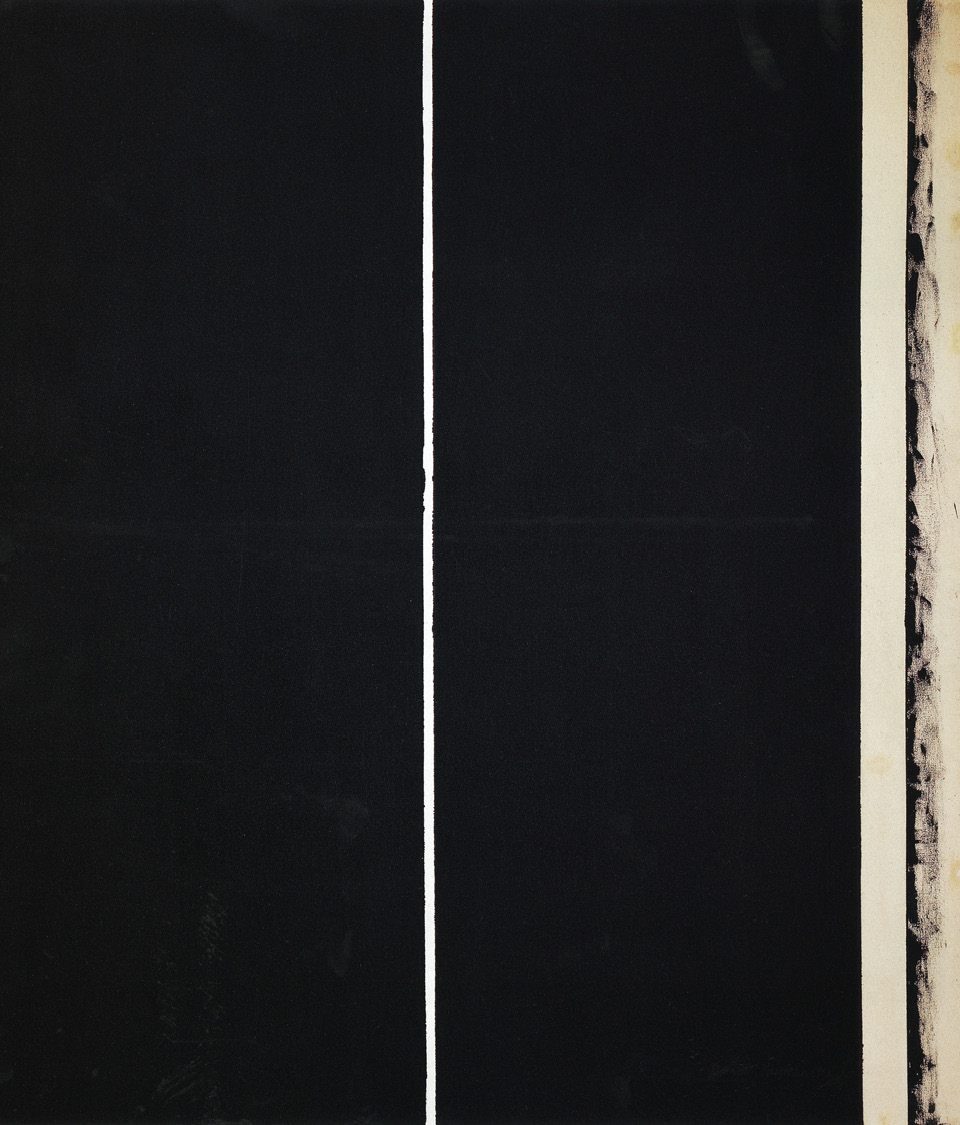

Death was no less crucial a concept to Newman. Abraham (figure 11.2) is not an exclusive reference to the Old Testament patriarch, but also, and more specifically, to Newman’s father, who bore the same name and whose death the painting is commemorating.70 If the intensity of the beam against its surrounding field in Moment or Be may supply an analog to the intensity of Da-sein, the close value contrasts in Abraham suggest the imminence of death, the eventual extinguishing of life, the gradual reclaiming of Da-sein by the void (Newman once referred to the “hard, black chaos that is death”71). It may be worth mentioning, if only parenthetically, that any belief in an afterlife would not mitigate the eclipsing of Da-sein at the moment of death. Da-sein, after all, means “Being” (Sein) that is “here” (Da). Even if there were life in the hereafter, the Being of Da-sein may still exist somewhere, but it would not be “here,” and thus no longer a Da-sein. From this perspective, the closeness in value between the black fields in Abraham is not necessarily a denial of an afterlife (although there is no reason to assume that Newman endorsed it either) as much as a recognition that death signifies the extinguishing of Da-sein.72

Figure 11.2. Barnett Newman, Abraham (1949), oil and magna on canvas, 82.75 3 34.5 inches. The Museum of Modern Art, New York, Philip Johnson Fund © 2012 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

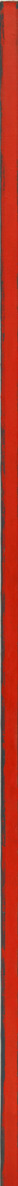

Similarly, given Heidegger’s referencing of human possibility in terms of expanses of open space, then the large dimensions of many a Newman canvas could be construed as analogs of our own potential, while narrower paintings such as Outcry (figure 11.3) or The Wild (figure 11.4) would represent the opposite: extreme anxiety, or analogs to situations where one feels one’s possibilities are severely constricted.73 Allegedly, Outcry was Newman’s response to suffering a heart attack, a work possibly reflecting the artist’s confrontation with death and distress over the curtailment of his potential. The narrowness of the canvas restricts the human presence almost to the very edge of its own physical, bodily contours, curtailing the spiritual openness, the spatiality of involvement uniquely characteristic of Da-sein. The unusual gestural quality of the piece also induces a degree of visual tension with the frame, as if the human presence fights or rebels against its constriction, against being forced to relinquish its as-of-yet unfulfilled potential—but in vain. With death, of course, all our possibilities vanish, and Da-sein returns to a literal spatiality no different than that of any piece of equipment. The Wild is more difficult to interpret. But if we return to the questions broached in the section on technology—namely, to the way the earth is threatened by exploitation—then the thin red stripe might evoke the wildness of nature. According to Hess, the title refers to the wildness of birds, of which Newman, an amateur ornithologist and avid bird watcher, was extremely fond.74 In the condition of wildness, birds are free, a condition for which the artist also struggles. The narrow configuration of The Wild suggests that, as in Outcry, what is strictly contained within the narrow edges is “enframed,” under stress, perhaps misused by human beings to its and their own detriment—facing annihilation, just like a person facing mortality. But, interestingly enough, Heidegger proclaimed that, under these severe conditions, “Wildness becomes the absolute itself and holds as the ‘fullness’ of being.”75 The Wild is also higher (95.75 as opposed to 82 inches) and markedly narrower (1 5/8 as opposed to 6 inches) than Outcry, a difference that, on the one hand, exacerbates its constriction, but, on the other, invites viewers, as Michael Schreyach has argued, to extend their perception “vertically into the space above and below the customary focal point of foveal vision.”76 Thus, despite their strong similarities, The Wild makes a markedly different impression than Outcry, as if the extreme lateral containment imposed by the frame is somehow successfully overcome by sensations of upward and downward expansion, a sensation accentuated by the bright redness of the zip in The Wild. Again, one is reminded, not only of Heidegger’s view that wildness holds the fullness of Being, but also that freedom cannot be attained nor constraints overcome, unless limitations are readily accepted.

Figure 11.3. Barnett Newman, Outcry (1958), oil on canvas, 82 3 6 inches. Mr. and Mrs. S. I. New-house, New York © 2012 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Figure 11.4. Barnett Newman, The Wild (1950), oil on canvas, 95.75 3 1 5/8 inches. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of the Kulicke family © 2012 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

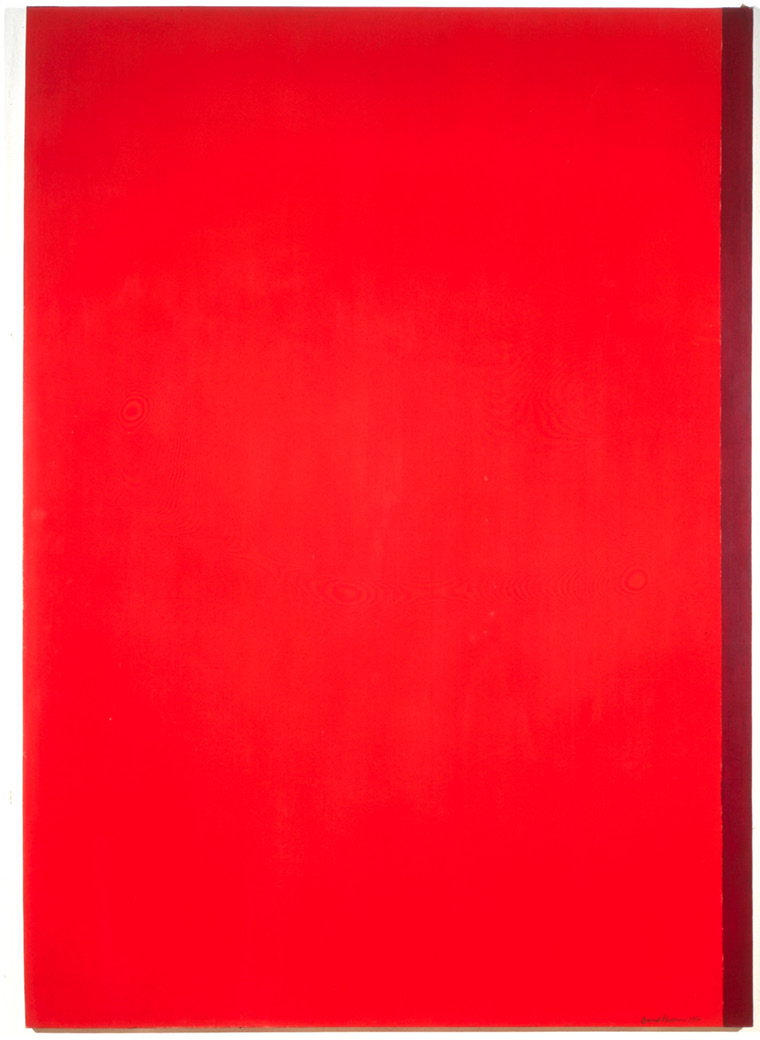

At a minimum, these differences also serve as a reminder of the singularity of Newman’s individual paintings. Just as feelings of freedom can emerge in physically narrow paintings, feelings of constriction may emerge in physically expansive ones. Roelof Louw observes, for example, that whereas our primary experience when perusing Eve (figure 11.5) is governed by the “the enveloping presence of the cadmium orange expanse. . . . The band on the right edge of the painting, by deflecting one’s attention away from the centre of the painting, also emphasizes the lateral expansion of the area, and stresses the edge as terminating one side of the painting.”77 This may explain Newman’s rejection of frames, on account, in his own words, of their “restricting content.”78 It seems that, seeking to generate sensations of freedom or containment from his work, Newman hoped these effects should result from elements integral to the paintings, elements he had created and placed himself, not ones extrinsic to the piece, or contingent upon another’s person’s decisions. Regardless, capping the lateral expansion of a painting by “termination” points (a stripe or the edge of the canvas) might therefore signify the absence of possibilities: mortality, perhaps, or any form of limitation. The effect is remarkably different than in, say, The Third (figure 11.6). The first beam, in bright yellow, a possible reference to an awakening state of presence, emerges from an irregular, chaotic area at the extreme left, a suggestion not so much of physical birth but of existential awareness. The second beam, no less bright, but now closer to the right edge, seems more delicate due to its frayed lines, the red having bled into the yellow area. The sense of presence is still active, but somehow more fragile and brittle, less self-assured, owing, conceivably, to the looming termination of the canvas nearby, a hint at mortality or the imminent absence of possibilities. Again, we might be confronting two human presences, or the same presence at different moments in time: at the left, when all its possibilities are “ahead” of it, and, at the right, when all of its possibilities are “behind” it. That might account for the first and second elements referenced in the title The Third. The last third, so to say, is the large expanse located at the center: the realm of possibility itself. Newman might be saying that we come into presence, not when we are born, but when we become fully aware (did he not identify the creation of Onement I as the “beginning” of his “present life”?79); invariably, we will confront the end of our existence, and our presence will return to nothingness. The fundamental question remains: What do we do with the time that has been allotted to us in between? How shall we seize the possibilities that are available? If we compare the wide area in between the bands in The Third to that of Tertia, a nearly identical composition, but far narrower, and with the right beam flush with the edge, the dramatically different effect becomes all the clearer. The possibilities are there, though more limited, and remain—where else?—in that space and within that time—between self-awareness and death—where the meaning of our existence, our potential, is to be determined.

Figure 11.5. Barnett Newman, Eve (1950), oil on canvas, 94 3 67.75 inches. Tate Gallery, London © 2012 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Figure 11.6. Barnett Newman, The Third (1962), oil on canvas, 101 1/4 3 120 3/8 inches. Walker Art Center, Minneapolis. Gift of Judy and Kenneth Dayton © 2012 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

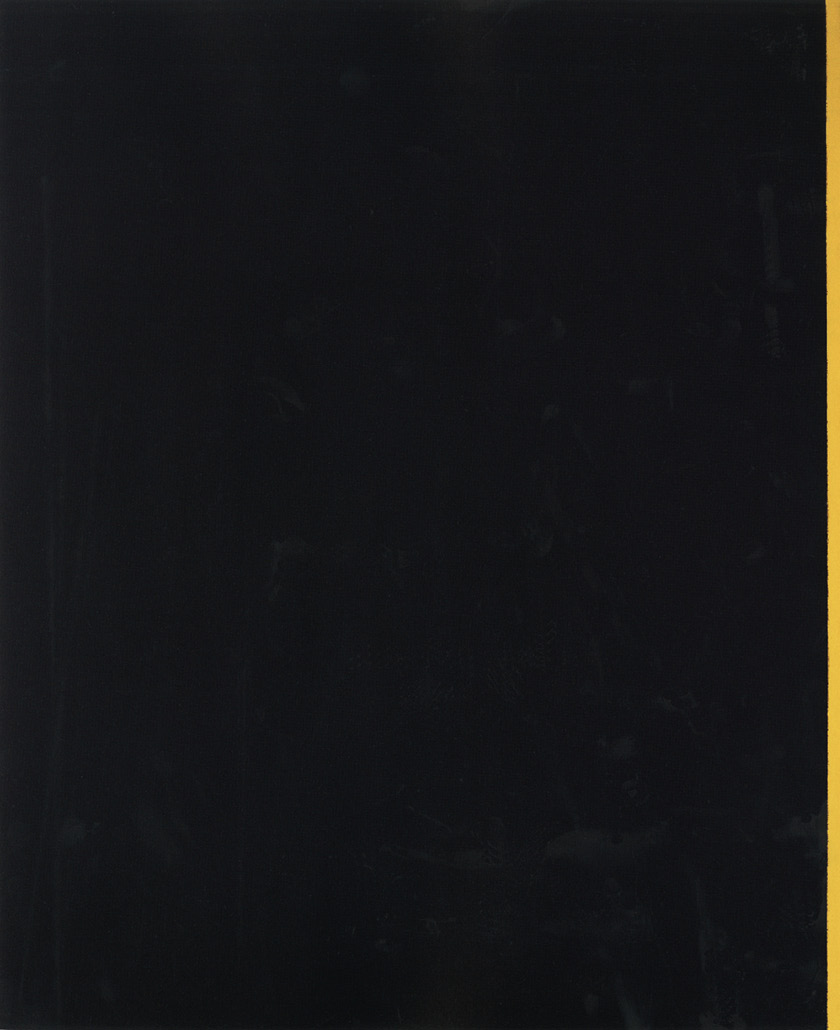

Intriguingly, Newman composed another work by recombining some of the same formal elements as in The Third, but in a radically different way. The Three is also painted on bare canvas, but exclusively in black (figure 11.7). If this color scheme were not enough to darken the overall tenor of the piece, the elements are introduced in reverse order. The first beam, unlike that in The Third, does not make its appearance until the approximate center of the painting, perhaps insinuating that the spark of self-awareness manifested itself only midway through the time-increment the work is meant to represent. In addition, the gestural traces of scumbling found at the extreme left of The Third, evoking the chaos from which the first beam emerged, is now found at the extreme right, at the “end” rather than at the “starting” point of the canvas. Coupled with the darker coloration, the overall impression induced is therefore more despondent. If The Third foregrounds the countless possibilities that life offers in that “space” between self-awareness and death, The Three evokes a late awakening, so late, perhaps, that the benefits normally accruing from an early heightened state of consciousness never came to pass. The rapid strokes at the “termination” of the canvas point to a sense of agitation, even despair, as if the possibilities that life put within one’s grasp were not fully realized. The effect is not only different from The Third but also different from Yellow Edge (figure 11.8), a remarkably minimalist piece, where Newman only animates a monochromatically black canvas with a yellow zip flush with the right edge of the painting. Placing the brightest portion of the work at the extreme right—at its “termination” rather than “starting” point—arguably compensates for the foreboding, ominous sensation induced by the dark coloration, and the disorienting imbalance induced by the radically asymmetrical composition. At least it allows the work to end, so to speak, on a positive note.

Figure 11.7. Barnett Newman, The Three (1962), oil on exposed canvas, 76.25 3 72 inches. Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Bagley Wright, Seattle © 2012 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Figure 11.8. Barnett Newman, Yellow Edge (1968), acrylic on canvas, 93.75 3 76 inches. National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa. Gift of Annalee Newman © 2012 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Accordingly, by manipulating placement and color, Newman sought to imbue a relatively limited visual vocabulary, the zips and the spaces that form between them, with a wide range of emotive associations. In a previous section, for example, it was proposed that Concord (figure 6.1) connotes the solidarity of two Da-seins forced to confront the vicissitudes of life in tandem; Shimmer Bright of 1968 (figure 11.9), arguably, conveys a similar meaning, but with a different set of connotations. As in Concord, and rarely for Newman, two beams betray the same color—bright blue, in this case—indicating the camaraderie between both human presences. But unlike Concord, where both zips are located dead-center (implying, metaphorically, that they face a common trial at the midway point of their lives), the zips in Shimmer Bright are located toward the extreme left of the canvas, as if they had far more “time” ahead of them. No less significant, the vast expanse of space to their right bears no evidence of the agitation caused by the gestural activity in Concord or The Three. What shimmers bright, as the title insinuates, is a future of immense and infinite possibility, as when we say, “These two have a bright future ahead of them.”

Figure 11.9. Barnett Newman, Shimmer Bright (1968), oil on canvas, 72 3 84 inches. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Gift of Annalee Newman © 2012 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

In these ways, Newman’s cryptic statements about “physical sensations of time,” or about time felt only “in private,” become more intelligible. Along these lines, Louw’s view is remarkably suggestive: that, in Newman’s pieces, each division “arrests attention” while, as a whole, paintings give the impression of being complete segments belonging “to a temporal continuum.”80 One might add that Newman’s physical sensations of time stand, metaphorically, for the way space can be used to evoke the presence, freedom, and potential of Da-sein, or, conversely, the lack of it. If vast, Newman’s canvases evoke the idea of possibility, that a human being is a not-yet, with all of its potential waiting to be realized. If narrow, the physical limits of the canvas evoke the constraints on our existence, the closing off of our possibilities (the making of a “not-yet” into a “never”). Additionally, Newman can expand narrow canvases by extending our vision vertically, or alter the spectator’s lateral vision by leaving the edges clear, or by providing the spectator with “termination” points, creating different visual sensations that, when metaphorically projected, stand for different existential situations. In Heideggerian terms, although Da-sein lies within bounds—physical, social, and chronological—Da-sein also has, at least within its lifespan, an infinity of choices. This does not mean that everything is open to it (the pedestrian cliché that everything is possible), only the view that, at all times, as long as Da-sein exists, possibilities exist. Only in death do possibilities vanish.

That such experiences are private is, in many ways, self-evident. No one can experience our past or our own potential. 81 But, on another level, if our cognizance of death triggers a recognition of authentic time as finite, and if death, as Heidegger stressed, is that supreme example of an experience that is uniquely and exclusively one’s own (i.e., that cannot be given over), then only authentic time can be felt privately. In fact, authentic time is the opposite of what Heidegger called “public time.” The latter is the dimension to which we are consigned as beings-in-the-world, the realm in which we encounter “things at hand and objectively present.”82 From this perspective, Newman’s emphasis on the privacy of time aligns perfectly with Heidegger’s. As an event that cannot be bypassed, death—the cognizance of which triggers an understanding of authentic time—is the most individualizing experience. Death, the philosopher writes, “does not just ‘belong’ in an undifferentiated way to one’s own Da-sein, but it lays claim on it as something individual. . . . [D]eath understood in anticipation individualizes Da-sein down to itself. This individualizing is a way in which the ‘there’ is disclosed for existence.”83 Facing mortality thus individualizes Da-sein, wrests its truth from the clutches of the they, gives Da-sein the freedom to confront its own impermanence, and sparks a more authentic understanding of time. In this sense, speaking of time as both physical and private is perfectly legitimate.

In view of the relationship Heidegger draws between death and authentic time, it is equally instructive to consider how time plays a role in the narratives to which Newman’s titles refer. Even if Abraham (figure 11.2) alluded to Newman’s own father, it is unlikely that a spectator would fail to associate the work with the Old Testament figure.84 Newman may have considered the odd symmetry between a son (himself) dreading the death of his father (Abraham) and a father (the biblical Abraham) dreading the death of a son (Isaac). Newman could also have compared the way his own life changed since the time of his father’s death with the Jewish patriarch’s own agony when anticipating the imminent death of his son at his own hands. In each case, the interested parties need to face their future with resolve and fortitude. In Prometheus, time is also integral to the narrative: the moment of extreme suffering when the hero’s liver will be devoured, and the anticipation of the gruesome moment’s repetition on a daily basis. Even at the core of the story of Achilles is the relation between death and time: the hero must chose between a short yet glorious life and a long yet uneventful one. His existence will hinge on choosing one of two possibilities: being inauthentic, undistinguished, common, or resolving to confront death with authenticity, steadfastness, and sublimity.

Whether these ideas indeed correspond to Newman’s stated intentions about inducing physical sensations of time must remain an open question, particularly in view of the difficulty of divining meaning directly from the visual appearance of his paintings. Sharpening the connections between Newman’s and Heidegger’s ideas on mortality might also rest, ironically, on the way humanity can resist the oppressiveness of death. If the meaning of Being lies in possibility, then death—a state of non-Being and the extinguishing of Da-sein—means the absolute elimination of all possibilities. This, as indicated above, may explain the darkness of Newman’s Abraham, as well as the closeness in value between its two fields. But referring to the end of Da-sein by the term “extinguishing” also segues naturally to its antithesis: namely, illumination. Newman frequently made references to light in his titles (e.g., Shining Forth [figure 12.6], Anna’s Light, Profile of Light, Shimmer Bright, Primordial Light) and one may suspect that illumination was his way of evoking the opposite of mortality and the extinguishing of presence conveyed in Abraham (think of the expressions we employ to suggest happiness: “her face just lit up,” or “he beamed as he heard the news”). Interestingly enough, Heidegger also referred to presence as illumination.85 And when he construed the awakening of Da-sein to the reality of Being, to its own self, or to its potentiality, he described this unveiling in terms of a metaphorical emanation of light. Of course, Heidegger’s references to “unveiling” or “illumination” should be taken figuratively, which explains, along similar lines, why he also used illumination in a metaphorical sense to suggest aletheia. The presence of all that is present to us, for Heidegger, is a form of illumination, by virtue of which beings shine forth in “radiance” or “self-disclosure.”86

As things enter into unconcealment, Being itself, though hidden, is revealed and declares itself in this clearing.87 In other words, since Being is not a being, it cannot manifest itself directly; Being is apprehended only in the light beings emanate. Intriguingly, while discussing the works of his friend and fellow Abstract Expressionist painter Adolph Gottlieb, Newman also referenced illumination by quoting a philosopher especially esteemed by Heidegger: Heraclitus. “It is gratuitous,” Newman wrote, “to put into a sentence the stirring that takes place in these pictures. But no one has a better right than the ancient Greek philosopher Heraclitus.

The perfect soul is a dry light

Which flies out of the body as

Lightning breaks from a cloud.”88

Yet one could make a legitimate case that Newman had his own work in mind, rather than Gottlieb’s. Heraclitus’s image of lightning breaking from a cloud, after all, sounds remarkably close to Newman’s description of his own work: in fact, when asked about the potential meaning of the stripes or “zips,” he replied, “I thought of them as streaks of light.”89

Newman’s citation of Heraclitus90 echoes Heidegger’s interest in the very same image: “It remains to ask whether in our relation to the truth of Being the glance of Being, and this means lightning (Heraclitus, fr. 64) strikes; or whether in our knowledge of the past only the faintest glimmers of a storm long flown cast a pale semblance of light.”91 The standard translation of Heraclitus Fragment 64 reads, “The thunder-bolt (i.e. Fire) steers the universe.”92 But given his own proclivity toward idiosyncratic interpretations, Heidegger retranslates the fragment to read, “But lightning steers (in presencing) the totality (of what is present).” Once the fragment is retranslated, Heidegger offers the following interpretation: “Lightning abruptly lays before us in an instant everything presencing in the light of its presencing. The lightning named here steers. It brings all things forward to their designated, essential place.”93 Elsewhere, Heidegger again stressed the importance of this image: “The question ‘What calls us to think?’ strikes us directly, like a lightning bolt.”94

The link Heidegger establishes between illumination and presence can even be extended to our discussion of time. Using Newman’s experience in Ohio, we surmised that humanity’s difference from nature sparked its sense of presence and place. As humanity stands apart from a world that is different, it comes to ponder its own history, the way its existence is restricted by chronological as well as other physical constraints, an awareness that also makes it uniquely “present” in a chronological as well as spatial way: “being present” means both “being here” or “existing in the now.” It is this aspect of standing out that Heidegger identifies in Heraclitus and then expresses, metaphorically, by means of illumination. The lighting, Heidegger confesses, “is no mere brightening and lightening. Because presencing means to come enduringly forward from concealment to unconcealment, the revealing-concealing lighting is concerned with the presencing of what is present.”95 As Being comes into presence, he adds, it “enters into its own emitting of light.”96 On this basis, if death extinguishes Da-sein into a state of non-presence, illumination brings Da-sein into the full light of presence as a manifestation of Being.

Turning to Newman with these ideas in mind, one may propose that, if the beams indeed stand for streaks of light, then another layer of complexity animates the artist’s version of the time-as-space metaphor. As already insinuated, we tend to read time sequentially as a path moving from left to right. Still, several beams in Newman’s early drawings and paintings, such as The Beginning (figure 2.4) and The Word I (figure 10.1), narrow toward the bottom, a solution the artist eventually abandoned, perhaps because of its perspectival associations. Yet connecting the beam with light (or lightning strikes) inevitably introduces another space-as-time metaphor: namely, that we will think of the beam as moving “downward.” If so, that occurrence, however brisk, also unfolds in time, as it does for any object rapidly falling under gravity. Intriguingly, although we tend to associate left with “past” and right with “future” in conformity with our writing system, the Chinese often speak of the past as “up” and the future as “down” in conformity with theirs.97 And given the uni-directionality of gravity, most objects fall more easily and with greater velocity than they rise. Accordingly, we assume that objects moving downward do so with greater momentum than those moving upward or even laterally, a visual effect upon which Newman relied while narrowing the beam in The Beginning.

One might even say the same of Newman’s zips in general—even if they do not narrow toward the bottom—especially if we are meant, as the artist intimated, to construe them as streaks of light (although The Wild, assuming Hess is right in stating that Newman associated it with the wildness of birds, would actually provide an exception, since it suggests upward ascension). Either way, the very term Newman preferred to designate the beams, “zip,”98 connotes this faster velocity. Unfortunately, the word is somewhat inelegant, accounting for its infrequent use in these pages. Even so, Newman’s choice reinforces the analogy being proposed here—as Steven Pinker put it, “Long words may be used for things that are big and coarse, staccato words for things that are sharp and quick.”99 In which case, Newman sought to trigger two separate sensations of time from the majority of his canvases: a slower lateral motion and a faster downward thrust (analogous, say, to a person ambulating slowly while an object falls directly before them). As the directions are different, so are the velocities. Yet, unlike the time-as-procession versus time-as-landscape metaphors, these two sensations are actually compatible. Though we cannot say, “We’ll cross that bridge as time goes by,” we can say, “I was walking down the street when, suddenly, it hit me.” Newman could easily have capitalized on these associations in order to differentiate two different temporal and existential situations. The leisurely pace of lateral motion evokes moving through a medium that offers a certain degree of resistance, and is thus appropriate to the slower tempo of remembering or anticipating. It is also consonant with Heidegger’s view of public time as the dimension in which we move on account of being thrown-in-the-world. The rapid descent, lightning-strike of the zip, conversely, recalls those sentences of Heidegger’s such as “Lighting is the . . . bestowal of presencing” or “the temporality of resoluteness has, in regard to its present, the nature of the Moment.” In this way, Newman could be creating different visual analogs of temporal experiences that tally with Heidegger’s descriptions of authentic versus inauthentic time. In one case, we move through a continuum, a sequence of ordinary “nows,” in conformity with social convention; in another, we are struck by a flash of inspiration, time becomes private, and we are brought back to ourselves.

In order to push these observations further, it is constructive to return, albeit briefly, to transitional pieces such as The Beginning (figure 2.4) and Moment (figure 2.5), both of whose compositions clearly lay the ground for, but cannot be completely assimilated with, Onement. It has long been acknowledged in the literature that, despite many key similarities with such transitional works, Onement I (figure 2.1) signals the dividing line Newman himself drew between his formative and mature style. One reason may be that the backgrounds around the zips in The Beginning and Moment still reveal a degree of gestural activity, a formal solution often in evidence in the artist’s drawings, but one the artist largely relinquished in his painterly production. Although the zips betray remarkable variety, in terms of color, width, brightness, and edge, the backgrounds, in general, tend to be homogeneous and uniform. This may seem like a trivial point. But in view of the different visual sensations of time his mature work is attempting to elicit—a slow, lateral pace versus a quick, downward thrust—it may have held a portentous meaning for the artist. The strokes at either side of the beam in Moment, for example, suggest that the background (the void) is active or in motion. If, during his mature phase, Newman decided to limit such color modulations in his backgrounds, the reason, arguably, was because he sought to reserve any evocation of activity or agency exclusively for the beams. In other words, he wanted Da-sein to have direction, and the void to be directionless.

If the zips in his abstractions portend a rapid moment of unusual intensity, Newman also came to realize that a greater degree of lighting displayed in the stripes heightens the level of that intensity. With its darkness and close-valued contrasts, Abraham (figure 11.2) stands for the heaviness, the non-presence of death; a painting such as Be (figure 2.10), for the lightness and luminescence of existence as it emphatically stands out against all that is.100 It is here, perhaps, that the relevance of Heidegger’s metaphorical way of reading Heraclitus emerges in sharpest relief. Heidegger believes human beings “are not only lighted by a light—even if a supersensible one—so that they can never hide themselves from it in darkness; they are luminous in their essence. They are alight; they are appropriated into the event of lighting, and therefore never concealed.”101 Lighting, therefore, is not simply “enlightenment,” or the lighting of what, on occasion, remains in darkness. Lighting is what occurs when the immateriality of Being is manifest in a being such as Da-sein. This is perhaps how all of the elements discussed in previous sections converge. Newman’s beams stand for a Da-sein emerging from its environment, feeling its own presence and acquiring a sense of its existential place in the world by differentiating itself from what is not Da-sein. The intensity of the value contrasts in the paintings measures this difference: the degree to which Da-sein is both physical and metaphysical, denoting how the light of Being manifests itself, however mysteriously, in the “there” of a human being. In the context of a physical canvas, moreover, the beams, surrounded by spaces that appear either to expand or contract, may also denote our place within the stream of time: whether authentic possibilities stand before us or not.

As already mentioned, Heidegger also conflated the manifestation of Being with illumination through the image of a horizon. In parallel with Newman’s title, Horizon Light (figure 11.1), Heidegger proposes that the “understanding of being already moves in a horizon that is everywhere illuminated, giving luminous brightness [italics in original].”102 Illumination, thus, is the effect of a primordial and authentic understanding of Being and time. Inasmuch as a horizon extends in physical space, Newman’s horizon may represent his own idea of time extending toward the future (as exemplified, say, in the everyday expression “time-line”); yet, given Newman’s reference to the privacy with which time is experienced, his image was unlikely to evoke the regularity and consistency of what Heidegger disparages as “public time.” Instead, Newman may have been invoking, especially if he used the trope of illumination figuratively, the idea of the possibilities time affords. On this account, the light set off by the horizontal beam is not a given, but represents the extent to which our possibilities are bestowed upon us provisionally, conditional upon our profound questioning of the meaning of our existence.

Grasping these possibilities, however, lies beyond the senses; they also elude detached, deductive reasoning. It may be compared, rather, to what Newman described as the “ecstasy man feels whenever face to face with deep insight,”103 and also reminiscent of Heidegger’s own concept of ek-istenz, which is also extrapolated from the idea of ecstasy, the idea of standing outside of, and going beyond, the self. According to Heidegger, the ecstasy of recognizing one’s own Being reflects Da-sein’s exclusive ability to stand apart from, and contemplate, its own self, explaining the inclusion of the hyphen in the term “ek-istenz.” To stand outside, and extend beyond, ourselves is crucial to authentic temporality: we “retrieve” our past and “project” ourselves into the future. In view of Heidegger’s views on art, it would stand to reason if art and poetry would encourage the very form of ecstatic illumination of which he speaks. “Through a merry gaiety,” the philosopher writes, the poet “illuminates the heart of men, so that they may open their hearts to what is genuine in their fields, towns, and houses. Through a grand gaiety, he first lets the dark depth gape open in its illumination. What would depth be without lighting?”104

Notes

1. SWI, 175.

2. Barnett Newman, draft of the Statement “Ohio, 1949,” Barnett Newman Foundation Archives.

3. BT, 22.

4. BT, 40.

5. BT, 98.

6. BT, 378.

7. Steiner, Martin Heidegger, 110.

8. An exception to this general rule, though no less a physical way of representing time, is typical of an Amerindian group called the Aymara. They consider the past to be forward and the future to lie in back, because, unlike the past, the future is unknown and cannot be seen. See Stefan Klein, The Secret Pulse of Time: Making Sense of Life’s Scarcest Commodity (New York: Marlowe, 2007), xvii.

9. BT, 342.

10. The idea of literally moving from one location to another also gives us a way to express the metaphorical idea of moving from one state to another: “I moved from point A to point B” underpins the concept of “things moved from bad to worse.”

11. See Bernard Comrie, Tense (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1985).

12. John O’Keefe, “The Spatial Prepositions in English, Vector Grammar, and the Cognitive Map Theory,” in Paul Bloom, Mary A. Peterson, Lynn Nadel, and Merrill F. Garett (eds.), Language and Space (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1996), 302.

13. BT, 335.

14. Martin Heidegger, Ontology—The Hermeneutics of Facticity, trans. John van Buren (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1999), 24.

15. SWI, 249.

16. SWI, 250.

17. FCM, 145.

18. Brock, Martin Heidegger: Existence and Being, 20. “The unity of the horizontal schemata of the future, having-been, and present,” Heidegger proclaimed, “is grounded in the ecstatic unity of temporality. The horizon of the whole of temporality determines whereupon the being factically existing is essentially disclosed” (BT, 334).

19. Yve-Alain Bois, “Newman’s Laterality,” in Reconsidering Barnett Newman, 34.

20. See Peter De Bolla, “Serenity: Barnett Newman’s Vir Heroicus Sublimis,” 41.

21. Yve-Alain Bois, “Newman’s Laterality,” in Reconsidering Barnett Newman, 44.

22. BT, 100.

23. William James, The Principles of Psychology (New York: Dover, 1950), 21.

24. IM, 44.

25. Stefan Klein, The Secret Pulse of Time, 55.

26. George Lakoff and Mark Johnson, Metaphors We Live By (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1980), 41ff.

27. See Barbara Tversky, “Spatial Perspective in Description,” in Paul Bloom, Mary A. Peterson, Lynn Nadel, and Merrill F. Garett (eds.), Language and Space, 469.

28. Lera Boroditsky, “Metaphoric Structuring: Understanding Time through Spatial Metaphors,” Cognition 75 (2000):1–28.

29. See Bernard Comrie, “Time and Language,” in Tense, 2.

30. Stefan Klein, The Secret Pulse of Time, 89.

31. In “Silent Visions: Lyotard on the Sublime,” Art & Design 10 (January/February 1995): 73, Renée van de Vall speaks of “the impossibility of an overview” in Vir Heroicus Sublimis.

32. Pinker, The Stuff of Thought, 195.

33. BT, 299.

34. BT, 299.

35. BT, 299.

36. BT, 299.

37. On Time and Being, 14.

38. On Time and Being, 14.

39. On Time and Being, 15. The complete citation is as follows: As a result, dimensionality “consists in a reaching out that opens up, in which futural approaching brings about what has been, what has been brings about futural approaching, and the reciprocal relation of both brings about the opening up of openness. Thought in terms of this threefold giving, true time proves to be three-dimensional.”

40. The Basic Problems of Phenomenology, trans. Albert Hofstadter (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1988), 234.

41. EGT, 53.

42. EGT, 53.

43. EGT, 53.

44. Pattison, The Later Heidegger, 144.

45. EGT, 53.

46. Martin Heidegger, “Remembrance of the Poet,” in Brock, Martin Heidegger: Existence and Being, 251.

47. The Stuff of Thought, 188.

48. On Time and Being, 16.

49. EGT, 54.

50. Barnett Newman interviewed by Karlis Osis, 1963, transcript, page 20, Barnett Newman Foundation Archives.

51. BT, 301–2.

52. BT, 302.

53. The Basic Problems of Phenomenology, 273.

54. BT, 303.

55. BT, 304.

56. BT, 310.

57. BT, 319.

58. BT, 311.

59. BT, 377.

60. SWI, 261.

61. “Da-sein can ‘suffer’ dully from everydayness, sink into its dullness, and evade it by looking for new ways in which its dispersion in its affairs may be further dispersed. But existence can also master the everyday in the Moment, often only ‘for the moment,’ but it can never extinguish it” (BT, 339). Since the meaning of Being is time, then the authenticity of Da-sein is thus predicated upon loosening the demands and concepts of time that are imposed upon Dasein from the they: “access to genuine temporality demands a reevaluation of the banal construct of past-present-future whereby we, almost invariably without giving it much thought, imagine and conduct our daily lives” (Steiner, Martin Heidegger, 109).

62. Comrie, Tense, 37.

63. BT, 377.

64. Pinker, The Stuff of Thought, 48.

65. Safranski, Martin Heidegger: Between Good and Evil, 115, 116.

66. SWI, 140. What is the difference in Newman’s work between the vertical versus the horizontal stripes? Perhaps the horizontal recalls a historical or chronological movement from past to present to future: we look ahead of ourselves, or we retrace the steps of our lives in a sequential, chronological way. The vertical, on the other hand, suggests an arrest in time, a motionlessness where one takes stock in the intensity of the moment. When one is overwhelmed, or even gripped, by the concerns of life, life becomes a question of anticipation, in which the intensity of the moment gets lost. We must bring life back to itself: a moment of heightened unrest. For Heidegger, similarly, the question of being is inseparable from the issue of temporality, and the meaning of being is time; there is no ideal of permanency; in its passing and in its happening, but time, itself, provides no precise meaning. Newman, similarly, also gives us no answers. As Safranski put it, “We are caring and providing creatures because we expressly experience a time horizon ahead. Caring is nothing other than lived temporality” (Martin Heidegger: Between Good and Evil, 157). For Heidegger (cited in Steiner, Martin Heidegger, 84), “Not until we understand being-in-the world as an essential structure of Dasein can we have any insight into Dasein’s existential spatiality.” We do not live “in time”; we “live time.”

67. Gelven, A Commentary, 75.

68. See Jeff Malpas, Heidegger’s Typology: Being, Place, World (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2006), 245.

69. Richardson, Heidegger: Through Phenomenology to Thought, 47, 166.

70. Hess, Barnett Newman (1969), 55. For an extensive discussion of Abraham, see Bois, “Abraham,” October 108 (Spring 2004): 5–27.

71. SWI, 108.

72. If, as Heidegger claims, “the essence of man is founded in the fact that he is that being to whom Being itself reveals itself, then the essential trans-mittal and the essence of ‘sending’ is the unveiling of Being” (P, 55). It is in man that this sending takes place, that this unveiling of truth, the luminous radiance of Being, is manifest. But this luminous radiance is synonymous with freedom and awareness, not with literal birth and death. One may be alive yet completely oblivious to the truth of Being. “For the Greeks,” the philosopher maintains, “death is not a ‘biological’ process, any more than birth is. Birth and death take their essence from the realm of disclosiveness and concealment” (P, 60). Newman also did not construe birth as a “biological process”; otherwise, he would not have referred to the creation of Onement I as the “beginning of my present life” (SWI, 255). But although awareness and the unveiling of truth do not coincide with one’s biological birth, there can be no denial that, at the point of death, that same awareness and unveiling, that same truth and radiance, is concealed. Though birth is not necessarily the emergence of presence, death is the opposite. “There prevails,” Heidegger adds, “a concealing appearing in the essence of death” (P, 76).

73. In this particular case, Stephen Polcari’s reading of The Wild and Outcry coincides with my own when he writes that “the central image and plane contrasting with the hard, clear edges of the canvas’s shape . . . [can be construed] as a metaphor for the shattering of the life journey.” See Stephen Polcari, Abstract Expressionism and the Modern Experience (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1991), 207.