Four

WHAT’S IN IT?

1899–1901

And yet while we eat

We cannot help asking, “What’s in it?”

In 1899 U.S. senator William Mason of Illinois asked for and received permission from Secretary Wilson for Wiley to serve as scientific adviser for a new series of hearings on the country’s tainted food and drink supply. Mason, a Republican from Chicago described by newspapers as “a champion of liberty,” had a reputation as a progressive legislator and a reform-minded opponent of machine politics.

The Mason hearings began that very spring, with meetings scheduled not only for Washington but also for New York and Chicago. They would continue for nearly a year, encompassing fifty different sessions and almost two hundred witnesses. The Chemistry Division would be nearly overwhelmed by the need to analyze hundreds of additional samples of food and drink. State public health officials lined up to testify, from Indiana’s Hurty, caught up in his state’s milk scandal, to the chief chemist from Connecticut, whose laboratory had discovered that spice processors in that state were burning old rope and using the ash as filler in ground spices such as ginger. Businessmen also testified, the honest ones decrying unfair competition from fraudsters. Representatives from the cream of tartar industry warned that baking powders were tainted with aluminum. Representatives from the dairy industry testified that makers of oleomargarine (by which they meant meatpackers) were still consistently mislabeling their product as butter.

Without federal help, dairy states had little recourse; the state of New Hampshire had tried requiring that all margarine be dyed pink, but the U.S. Supreme Court had struck down that legislation in 1890, declaring it an illegal tax. Dairymen complained at the Mason hearings that margarine makers were nothing but cheats and liars. The meatpackers, in turn, accused the dairy industry of being stuck in the primitive past. Anyone, they insisted, could tell the difference between old-fashioned, often rancid butter and ever-fresh oleomargarine, which was “a product of the advanced age.”

At Mason’s request, the Chemistry Division’s Willard Bigelow had looked again at dishonesty in the wine industry, finding the usual preservatives, such as salicylic acid, swirling through many bottles. He’d also found many bottles that were labeled as wine but were merely factory-produced ethanol colored with coal-tar dyes and flavored with fruit peels. One wine dealer, when visited by Bigelow posing as a shop owner, had asked “what distinguished label” his visitor desired. He’d taken Bigelow’s list and then, while the chemist watched, filled everything from the same cask, simply pasting labels on the different bottles to identify them as claret, Burgundy, or Bordeaux.

For almost every food product, the Chemistry Division could point to a trick involved in its manufacture. Doctors continued to worry over continued reports of “grocer’s itch,” a side effect of the deceptive practice of grinding up insects and passing the result off as brown sugar. Sometimes live lice survived the process. Beer, which most consumers imagined to be derived from malted barley and hops, was often made from a cheaper ferment of rice or even corn grits. So-called aged whiskey often was still routinely rectified alcohol, diluted and colored brown. As Wiley had found twenty years earlier at Purdue, corn syrup was widely used as the basis for fake versions of honey and maple syrup.

Many manufacturers argued that they had to fake products to stay competitive. Detroit canner Walter Williams, of Williams Brothers, described the making of his Highland Strawberry Preserves. The jam was, he said, 45 percent sugar, 35 percent corn syrup, 15 percent apple juice made from discarded apple skins, some scraps of apple skin and cores, and usually one or two pieces of strawberry. The strawberries cost him, he added. Many comparably priced preserves were just glucose, apple juice, red dye, and timothy seed added to simulate strawberry seeds. “If we could sell pure goods, I would be pleased,” Williams insisted. “I believe they should be labeled, showing their ingredients and showing the quality of the goods.” But as there was no law setting such standards and as he had to compete with less scrupulous canners, there was no way for him to stay in business unless he cut costs to match.

Wiley testified that about 5 percent of all foods were routinely adulterated, with the number being much higher—up to 90 percent—in categories such as coffee, spices, and “food products made for selling to the poor.” This proved to be a little too sedate a summary for some of the tabloid journals; reporters exaggerated his testimony, stating that Wiley believed 90 percent of all food and beverage products to be adulterated. The careless reporting dismayed Wiley, his boss Wilson, and even the president—especially after alarmed American trade representatives wrote from Europe that grocers there were talking about boycotting U.S. food entirely. Wilson had to send clarifications and copies of Wiley’s actual testimony to the State Department in order to reassure importers of American food and drink.

In other testimony, Wiley concentrated on preservatives and dyes. For example, he cited the practice of improving the color of canned peas by spiking them with copper sulfate and zinc salts. In small doses, these metals might pose little risk, he said, but no one really knew what those safe doses were. As he had earlier, he also warned of a possible cumulative dose: Who could ensure that a steady diet of the stuff, over months or even years, wouldn’t lead to heavy metal poisoning? Another witness, chemical physiologist Russell Chittenden of Yale University, echoed that point even more strongly, warning that most people eating canned vegetables would eventually be harmed by repeated exposure to metals. He urged that copper, in particular, be banned as an additive from American food products as soon as possible.

Wiley again emphasized that the biggest worry was for vulnerable populations: young children, people with chronic health problems, and the elderly. Those with a healthy stomach, as he put it, were unlikely to be harmed by an occasional exposure to copper or zinc. The problem was that no one was sure who would be harmed: “Many people they do hurt and the least possible amount upsets the digestion.”

Unlike Chittenden, Wiley did not urge an immediate ban. Rather, Wiley told the assembled senators that such regulations needed to be grounded in good science. He urged that the government invest in studying the health effects of such additives. If risks were clearly and methodically identified, then those compounds should be removed from all food and drink. And, somewhat wearily, he once again recommended that manufacturers be required to tell consumers, on labels, what was being mixed into their products. “Were it as harmless as distilled water,” he said, “there would be no excuse of its addition to food without notification to the consumer.”

State food chemists also expressed dismay over the new additives. A. S. Mitchell, food chemist for the state of Wisconsin, brought to the hearings samples of three of the most popular new preservatives: Rosaline Berliner, Freezine, and Preservaline, the formaldehyde-rich culprit in the Indiana milk poisonings. He pointed out that none of them had been safety-tested; that all of them had been found in samples of commercially sold ice cream, cottage cheese, beef, chicken, pork, and shellfish; and, finally, that none of those foodstuffs bore a label listing ingredients.

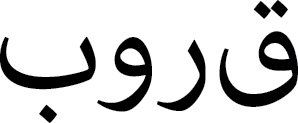

With the Rosaline Berliner, Mitchell highlighted what he saw as the alarming increase in the use of its active ingredient—sodium borate, or borax. A naturally occurring mineral salt, it had been used in various forms of manufacturing for centuries. The name came from the old Arabic word būraq (

), which meant white. First discovered in the dry lake beds of Tibet, the powder, which easily dissolved in water and could be used to enhance enamel glazing, had been traded along the Silk Road as early as the eighth century CE. But its modern use had been driven by discovery of vast deposits of borax in California and by the aggressive marketing of the Pacific Coast Borax Company. A Wisconsin-born miner named Francis Marion Smith, with a natural flair for marketing his product, had founded the company. Smith, known to consumers as the “Borax King,” had purchased the rights to a rich vein of borax in the Mojave region, known as the “Twenty Mule Team Mine” for the long wagon trains used to haul out the mineral deposits. On the advice of his manager, he developed a cleaning formula promoted as “Twenty Mule Team Borax” for its powerful action and then went on to market his product for that and many other uses, including as a handy preservative.

), which meant white. First discovered in the dry lake beds of Tibet, the powder, which easily dissolved in water and could be used to enhance enamel glazing, had been traded along the Silk Road as early as the eighth century CE. But its modern use had been driven by discovery of vast deposits of borax in California and by the aggressive marketing of the Pacific Coast Borax Company. A Wisconsin-born miner named Francis Marion Smith, with a natural flair for marketing his product, had founded the company. Smith, known to consumers as the “Borax King,” had purchased the rights to a rich vein of borax in the Mojave region, known as the “Twenty Mule Team Mine” for the long wagon trains used to haul out the mineral deposits. On the advice of his manager, he developed a cleaning formula promoted as “Twenty Mule Team Borax” for its powerful action and then went on to market his product for that and many other uses, including as a handy preservative.

Borax was already known at that point as both a cheap and versatile preservative. It slowed fungal growth and it appeared to inhibit bacteria as well. Long before Smith’s industrious marketing, food manufacturers had been gradually taking up its use. Meat producers had started using it in the mid-1870s, after British importers had complained that American bacon and ham tasted too salty. The dairy industry had followed by using borax as a butter preservative, again avoiding a salty taste. During the Mason hearings, one dairy spokesman suggested that the British had, in fact, come to prefer the slightly metallic taste of borax in butter. The meatpackers used borax to preserve everything from canned meat to oleomargarine. In a rare moment of agreement, they joined with dairy representatives in attacking complaints like Mitchell’s, pointing out that refrigeration options were extremely limited when sending products overseas. One could do only so much by packing with ice; it served no one to sell slimy meat and rancid butter abroad. The meatpackers also moved to quell the suggestion that borax might not be a healthy additive. They hired toxicologist Walter Haines, from the University of Chicago, to assure the Senate that borax was safe. Haines didn’t exactly stick to script. He said that he’d seen no convincing evidence that borax was harming people but refused unambiguous endorsement. For the moment, Haines explained, illnesses caused by decaying foods, the dreaded “ptomaines,” seemed to him to be a far worse option.

Such scientific caution failed to satisfy preservative makers, whose position was made clear by Albert Heller of Chicago, manufacturer of the formaldehyde-infused Freezine. Yes, Heller said, Freezine was now used in everything from cream puffs to canned corned beef. But American consumers were lucky to find it there. By preventing decay, it reduced the number of illnesses caused by the ptomaines. For all he knew, it reduced other terrible diseases like cholera as well. The American public should embrace chemical preservatives, he argued, and smart consumers already did. “I wish to say that every one of us eats embalmed meat and we know it and we like it,” Heller said.

In the early spring of 1900, after reviewing the hearing testimony, Senator Mason delivered a fiery speech on the Senate floor. “This is the only civilized country in the world that does not protect the consumer of food products against the adulterations of manufacturers,” he charged. The country’s food was full of aluminum, “sulfuric acid, copper salts, zinc and other poisonous substances.” And if it wasn’t contaminated with toxic substances, it was faked, disguised, or otherwise adulterated. He’d had enough and he hoped the American people and his fellow legislators felt the same, Mason said. He was proud to introduce legislation that would require safety testing of additives and substitutes and prohibit those found dangerous. Further, his pure-food bill would require accurate labeling of all ingredients. If it passed, companies that failed to comply, he added, would be fined or even taken to court. He was proud to announce that comparable legislation was being introduced in the House.

The whole parade of food and drink manufacturers—dairy, meat, eggs, flour, baking soda, beer, wine, whiskey—not to mention the chemical companies, immediately lined up against the legislation. Despite his strong language in support of the Senate bill, Mason warned Wiley privately to expect its failure. The sponsor of the House version of the bill, Congressman Marriott Brosius from Pennsylvania, was equally pessimistic. His assessment, as he also told Wiley, was that the most positive result was likely to be simply keeping the issue “before the public eye.”

Within weeks, both bills were shut down in committee by legislators friendly to the different manufacturing interests. It was frustrating, Wiley wrote to Mason, because he did think public support was turning their way. He’d collected dozens of newspaper clippings about the Mason hearings and every single one of them had applauded the action of the committee.

Many people also had written directly to Wiley requesting copies of committee testimony, issues of Bulletin 13, and even a tongue-in-cheek piece of doggerel that Wiley had written for a Pure Food Congress and impulsively decided to read aloud as part of his testimony. The verses, also published in New York’s Pharmaceutical Era Weekly, concluded pointedly:

The banquet how fine, don’t begin it

Till you think of the past and the future and sigh,

“How I wonder, I wonder, what’s in it.”

That same spring of 1900, in late May, Wiley proposed marriage to Anna Kelton. Her written answer—though not an immediate refusal—was less welcoming than he’d hoped it would be. “What worries me most of all is that I am not happier,” she wrote to him. “I had always pictured to myself that love would be consuming and overwhelming in its joy and I am on the verge of tears. What is the matter with me do you think?” She was painfully aware of the great age difference, of her mother’s staunch disapproval, and most of all of her own ambition to be independent and self-sustaining. “Browning’s line about ‘the best is yet to be’ comes into my mind but still this hobgoblin thought keeps popping up and it is that I am sacrificing my ideals, however childish they may be.”

Late that month, she called it off. “I am only full of reproaches for myself and for my weakness and lack of womanliness in not knowing my own mind and for letting you even this week harbor any hope of my sharing your future life,” she wrote. “But oh please believe it is that same honesty in me that before you admired which now makes me tell you this before it is too late.” She said she lacked that “sacred, sweet, overpowering feeling” that should accompany real love. “And so goodbye,” she concluded. “Goodbye with respect and the sincerest regards, I am always yours, Anna.”

Wiley couldn’t bring himself to accept that as a final answer. A brief separation was pending—he’d been appointed to represent the Agriculture Department that summer in Paris, at the Exposition Universelle de 1900, and to organize an exhibit there showcasing the excellence of American wines and beers. With some difficulty, he persuaded her to wait until he returned from France, suggesting she take some time to think things over before definitively telling him no. They held on to that fragile truce until he sailed in mid-July. But he was still shipboard in the middle of the Atlantic when Anna Kelton requested and received a transfer from the Agriculture Department to the Library of Congress. “When I left for Paris I had a perfect understanding with her but I had not been here long before I received a very sensible letter from her saying that she had concluded that our agreement had better be terminated,” he wrote to a friend. “At the same time I gathered from what she wrote that she had been influenced in this by her family.” They thought, he knew, that it was wrong for a man of his age to court a woman in her twenties. But “I have yet to learn that loving a pretty girl in a proper way and being loved by her in return has anything blameworthy in it.”

To Anna he wrote a tender good-bye letter. “You say, ‘Why don’t you make me love you?’ Love, dear heart, does not come by making nor does it go by unmaking. . . . I want you to know, dear heart, how much zest you have brought into my life.” She did not reply. But still he could not bring himself to remove her photo from the inside cover of his pocket watch.

Secretary Wilson wrote to Wiley in Paris to celebrate the good reception that he and his exhibit on alcoholic beverages had received, “which pleases me very much.” Wilson also added a note of reassurance regarding job stability. The next presidential election was coming up in November. “The campaign has not yet opened up but the indications are quite good regarding Mr. McKinley’s re-election.”

McKinley had been forced to select a new running mate, as his popular vice president, Garret Hobart, had died in November of 1898. After much political wrangling, the party had chosen the progressive New York governor Theodore Roosevelt to take his place. McKinley’s closest advisers were unenthusiastic: Roosevelt had not backed McKinley’s nomination in 1894 and Roosevelt had an un-McKinley-like reputation as a reformer. But that turned out to be a major campaign advantage.

The Democrats had once again named William Jennings Bryan, who had lost to McKinley four years earlier, as their candidate. As the campaign began, Bryan fiercely attacked McKinley as a corporate insider, a president beholden to banks and railroads. As he was close to those industries, McKinley decided to keep a low profile. The president gave only one speech during the campaign. The energetic Roosevelt, by contrast, gave more than 673 speeches, in 567 cities and towns, in 24 states. On November 3, Election Day, McKinley and Roosevelt won by a wide margin. Wilson’s job was secure for another four years and—as the secretary had predicted—so were both his chief chemist’s job and his food safety crusade.

In 1901, shortly after McKinley’s inauguration, Anheuser-Busch of St. Louis and Pabst Brewing Company of Milwaukee wrote to Wiley asking for analyses of their new “temperance beverages.” These bottled malt brews, with little alcohol content, were a relatively new take on the concept of “small beer,” which had been around in one form or another at least since medieval times, when it was often served to children. The big American brewers, producers of higher-alcohol beers and ales, began making temperance beverages to sell to nondrinkers and former drinkers and to curry favor from increasingly prominent anti-alcohol activists.

The Woman’s Christian Temperance Union had been organized in the early 1870s with the stated goal of “achieving a sober and pure world.” It was far from the first American temperance organization, but along with the Anti-Saloon League, organized in 1893, the WCTU had become one of the most strident and effective forces opposed to alcohol consumption. With its slogan, “Agitate. Educate. Legislate,” the WCTU linked this cause to another growing social movement, that of women’s suffrage. Frances Willard, WCTU leader, saw suffrage as a key to power. She argued that if women had the vote, they could better protect their communities from drunkenness and other vices. By 1901 the organization boasted more than 150,000 members nationwide. Its activism—and growing popularity—was making American brewers and other alcohol producers increasingly nervous.

So the brewing companies had double hopes for their temperance beverages: new markets plus the alleviation of hostilities. Wisconsin-based Pabst had two years earlier gotten the Chemistry Division to analyze its Malt Mead, seeking a stamp of approval to help market it. The lab had confirmed that the drink contained less than 2 percent alcohol. Now the company wanted Wiley’s support for another new low-alcohol beverage called Nutria. Pabst intended to sell it in Indian Territory (in the eastern half of what is now Oklahoma), where tribes including the Cherokee and Muscogee had been resettled after they were forced from ancestral lands in the Southeast. Pabst’s complaint was that the Department of Indian Affairs, which prohibited the sale of any alcoholic beverages in Indian Territory, had analyzed Nutria and declared it an intoxicating drink. It was shoddy chemistry, the company complained. Could Wiley’s more able crew set things right? The Chemistry Division’s analysis confirmed Pabst’s position and Nutria went on sale in Indian Territory.

Anheuser-Busch, meanwhile, had created a drink called American Hop Ale, essentially a beer-flavored soft drink, and wanted Wiley and Bigelow to analyze it so that the company could use the official Chemistry Division findings as part of its marketing campaign. The chemists complied, and Wiley wrote to the company to inform it that the division had detected traces of alcohol in the product. This, the brewery responded, was merely a preservative. “This is our secret,” a reply from Anheuser-Busch explained, but surely it didn’t alter the basic nature of the beverage? “Could not a small percentage of alcohol be added to the soft stuff to make it keep?” It could, the Chemistry Division allowed, and shortly later the company launched a new near-beer campaign.

In May 1901 the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo opened. This latest world’s fair, with its dazzle of electric lighting powered by nearby Niagara Falls, sprawled across 350 acres and celebrated the new century under the slogan “Commercial well-being and good understanding among the American Republics.” As part of the U.S. government’s contribution, the Agriculture Department presented exhibits featuring innovations ranging from new crops to modern farm machinery. Wiley’s scientific division, now renamed the Bureau of Chemistry, participated with three displays, two of which—one highlighting the sugar beet industry, the other celebrating experimental use of plant products in road building—fit the fair’s theme and a third, organized by Willard Bigelow, on “Pure and Adulterated Foods,” that defiantly did not.

Bigelow’s exhibit was made eye-catching by some brightly dyed flags, which were labeled as exemplifying the coal-tar agents used to color food and drink. It also featured a display of faked products, ranging from vinegar to whiskey, highlighting a newly developed technique of adding soap to rectified alcohol to simulate the way aged bourbons would bead and cling on glass. But perhaps the most pointed section dealt with the rising tide of new industrial preservatives. On these shelves were not only food samples but also glass jars and beakers containing preservatives extracted from everyday foods. The exhibit divided preservatives into “undoubtedly injurious, such as formaldehyde, salicylic acid, and sulfites” and possibly injurious, such as borax and benzoic acid.

“It is claimed by those interested in their use that the amount of preservatives added to foods is so small as to be unimportant.” But in this time of no food safety regulation, “small” was left entirely to the discretion of the manufacturer. Some foods were basically soaked in the new compounds. Or as Bigelow put it: “The amount added sometimes greatly exceeds that which is believed to be necessary by those who favor the use of chemical preservatives.”

The popular exposition ran for seven months and attracted eight million visitors, including President McKinley, who arrived in early September to make a speech against American isolationism. On the afternoon of September 6, he stood at the head of a receiving line in the exposition’s grand Temple of Music, cheerfully shaking hands with enthusiastic citizens. Reporter John D. Wells of the Buffalo Morning News, assigned to cover the event, stood taking notes, carefully describing each encounter. He would later recount that when one smiling young man got up to the president, he raised his right hand, which held a pistol wrapped in a handkerchief. Leon Czolgosz fired the pistol twice. The first bullet grazed McKinley’s chest. The second ripped through his stomach and sent him stumbling backward. The assassin was jumped by both police and attendees and transported to the local jail; the gravely injured president was rushed by ambulance to the local hospital.

Still, doctors reassured Vice President Roosevelt and cabinet members who had rushed to Buffalo to be by McKinley’s side that the wounds were not fatal. The president was expected to recover. Roosevelt departed for a working vacation in Vermont, where he was scheduled to address the state’s Fish and Game League. But the local Buffalo doctors, refusing to use newfangled X-ray machines, had not successfully removed all the debris left by the fragmenting bullet or fully sterilized the internal injuries. The wounds became infected, gangrene set in, and on September 14, nine days after the shooting, McKinley died.

Roosevelt rushed back—cobbling together a trip by horse, car, and train—to take the oath of office. He received a less-than-enthusiastic welcome from reform-wary leaders of his party. “I told William McKinley it was a mistake to nominate that wild man at Philadelphia,” said Senator Mark Hanna of Ohio. “Now look, that damned cowboy is president of the United States.”

Czolgosz, a former steelworker and a self-proclaimed anarchist, was rapidly charged, tried, and convicted. He received the death sentence, at the unanimous recommendation of the jury, and died in the electric chair at Auburn (New York) Prison on October 29, just forty-five days after the shooting.

In the weeks after McKinley’s death, Roosevelt sought at first to reassure the country: “In this hour of deep and terrible bereavement, I wish to state that I shall continue unbroken the policy of President McKinley for the peace, prosperity, and the honor of the country.”

But the new president was biding his time. In February 1902, Roosevelt’s administration filed an antitrust suit against a giant holding company created by a consortium that included such Gilded Age titans as J. P. Morgan, Cornelius Vanderbilt, and the Rockefellers. The Wall Street Journal angrily called it the greatest shock to the stock market since McKinley’s assassination. By contrast, Harvey Wiley was pleased to see the president show his more volatile, reformist side and hoped to see pure food and drink become one of Roosevelt’s causes. Unfortunately Wiley had stumbled already, and stumbled badly, in the opinion of the new chief executive.

Since his adventure in Cuba, Roosevelt had become a booster of the newly independent island country. With the support of Elihu Root, the secretary of war, the president proposed an agreement that would, among other things, foster economic growth by reducing the American tariff on Cuban-grown sugar. In January 1902 the House Committee on Ways and Means began hearings on the issue. Wiley, long considered an expert on the growing and processing of sugars, was called to testify.

Wiley feared that if the tariff on Cuban sugar was lowered, powerful American companies would see an opportunity for easy profit, buy up the imports, and resell them to American consumers at higher prices. The losers, he suspected, would be American farmers, undercut by the Cuban competition. He didn’t want to say all of this, however, in a public hearing. He knew it wouldn’t sit well with Roosevelt, but he wasn’t willing to testify contrary to what he believed. So Wiley asked Secretary Wilson to get the congressional summons withdrawn. “‘If I go up there I shall tell what I believe to be the truth and thus get in trouble,’” wrote Wiley, quoting himself in his conversation with the secretary.

Unfortunately for Wiley and his future relations with Roosevelt, Wilson shared the chemist’s reservations about Cuban sugar and wanted those doubts to be aired in testimony before Congress. Wilson also knew he’d damage his own standing with the president if he delivered the testimony himself. As a member of the cabinet, he said, he dared not say what he thought. Wiley could. The chief chemist agreed, reluctantly, to be a witness and, characteristically, he spoke his mind. “I consider it a very unwise piece of legislation and one which will damage, to a very serious extent, our domestic sugar industry,” Wiley testified. “Do you contemplate remaining in the Agricultural Department?” a legislator asked as other committee members burst out laughing.

The president was not amused. He summoned Wilson to demand that the chemist be fired on the spot. Wilson, realizing the extent of the damage he’d done to his subordinate, told the president that the chemist had been following departmental orders. It would be wrong to fire Wiley for doing what he was told, said the secretary. Grudgingly, Roosevelt agreed. He sent Wilson back with a message for the chief chemist: “I will let you off this time but don’t do it again.” Later that year, Roosevelt successfully negotiated a treaty that included a 20 percent tariff reduction on Cuban sugar. “I ran afoul of his good will in the first months of his administration,” Wiley later wrote ruefully. “I fear that this man with whom I had many contacts after he became president never had a very good opinion of me.”