3

Rehabilitating the “Subnormal [Métis] Family” in Saskatchewan

“At the zone of contact the scene is confused and turbulent.”

− 1954 Report, Native Welfare Policy, Department of Natural Resources1

Between 1944, when the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF) came to power, and 1962, the Social Democratic CCF government in Saskatchewan undertook a shift in Métis policy from one that was premised on racial difference to that of colour-blind integration. The competing logics at work in this undertaking came about initially in response to settlers’ demands for removal of Indigenous presence in their midst, followed by the application of CCF’s distinctive ethos of rationalizing and individualizing Indigenous peoples. CCF policies of integration not only secured lands and resources from Indigenous peoples, but also attempted to alter subjectivities by rehabilitating the hearts and minds of Métis peoples to embrace the Canadian way of upward mobility, nuclear families, and urbanization. By analysing Premier Tommy Douglas’s Métis removal and relocation policies, one can witness a sequence of overlapping and conflicting logics at work indicating a paradigm shift underway soon after the war in Canada. This era is a critical chapter in the history of social work, when Canadian society moved from embracing the promises of eugenics to rehabilitation. The introduction of the Métis colony scheme reflected a logic rooted in the biological/racialized nineteenth and early twentieth century, which then shifted toward a new and insidious form of welfare colonialism. Like other well-intentioned schemes to improve the human condition, these policies ended up inflicting more harm than good on the communities they sought to help.2 The modernist effort to socially engineer Métis peoples to embrace the values of middle-class Canadians was tainted by conflicting settler-colonial objectives that racialized Métis peoples and recast their political efforts to secure a land base as a welfare problem in need of a welfare solution.

The unique historical context in post–Second World War Saskatchewan provides historical context for an essential aspect of the origins of Indigenous transracial adoption. In June 1944 T.C. Douglas and the CCF came to power in the provincial election, winning forty-seven out of fifty-three ridings and making it the first social democratic party to be elected in North America. From the outset, the impoverished Métis and Indian communities in Saskatchewan were an area of personal concern for the premier. Bolstered by its overwhelming majority, Douglas’s CCF undertook sweeping reforms in child welfare legislation and Métis rehabilitation. From 1944 onward, the party grappled with developing a Métis and Indian policy that would fit with its social democratic ethos of “humanity first.” The philosophy was an all-encompassing ethos that sought to integrate all Saskatchewan citizens into society by equalizing access to education, health, and welfare. However, this policy was at odds with fulfilling the ongoing imperatives of a white settler-colonial hinterland.3 These conflicting objectives affected the direction undertaken and certainly the outcomes of Native policies, particularly in child welfare. This chapter explores the little-known history of the CCF Métis rehabilitation policy in Saskatchewan. It argues that the focus of rehabilitation gradually shifted from rehabilitating Métis families and male heads of households to rehabilitating women and children. Through child welfare legislation and the provision of child welfare services such as fostering and transracial adoption, Saskatchewan’s child welfare system incorporated the Métis children of its failed rehabilitation attempts. The process has obscured the impact of racialized poverty and loss of land. Instead, the CCF strove to demonstrate an image of cultural superiority and benevolent generosity.

Métis people in Saskatchewan did not disappear after 1885. Instead, during the critical years from 1900 to 1950 the contemporary political and national identity was formed.4 Métis communities continued to exist in both the northern and southern portion of the province. For Métis, the years after 1885 were difficult and formative. Like the Métis in Manitoba and Alberta, poverty, lack of economic opportunities, aggressive pursuit of Métis lands by rural municipalities, and poor crop years meant that Métis who did obtain lands in exchange for scrip ended up landless. In Saskatchewan, many Métis moved to the edges of Crown lands, forming communities that were known as road allowance communities.5 Physically and metaphorically on the margins of Prairie society, the Métis road allowance communities reflected Métis kinship patterns and enabled a form of political and cultural autonomy. Métis men worked as seasonal labourers for local farmers, clearing roots, picking rocks, and helping at harvest time.6 Since they did not own their property, they did not pay taxes and, as a result, were prohibited from sending children to local schools or accessing adequate medical care. Despite the marginalization, Métis men’s labour provided an essential component of the rural economy prior to large-scale mechanization after the Second World War. With lands cleared and with mechanization underway, Euro-Canadian farmers deemed Métis labour unnecessary and increasingly perceived the Métis road allowance communities as “embarrassments” and demanded their removal.

The virulent racism directed toward the Métis had existed in unvarnished form since 1885.7 In this period, Maria Campbell and Howard Adams have poignantly recounted the dehumanizing racism directed at Métis in Saskatchewan.8 White residents feared the Métis posed a health threat to white communities in close proximity to Métis road allowance communities. Writing to the provincial government in 1943, concerned citizen Antoinette Draftenza felt that the government should intervene, at least for the sake of the children. She believed that “the children are intelligent and could be taught to become respected citizens.”9 She likened the Métis to biohazard: “If we know that animals are roaming at large spreading dangerous diseases, every effort would be made to check them, yet our Métis come into our business offices and stores, mop our counters with their trachoma and otherwise infected rags and handle foods which other unsuspecting people must touch or purchase. They eat out of garbage cans; not from choice but because they are hungry. What a pity any Canadian child should have to grow up to an existence like that.”10

She proposed the government provide health care and education to the children. Draftenza saw the potential for education and health care to instruct the Métis in embracing Euro-Canadian standards of living through which Métis bodies could be reformed and made healthy prior to integration. Through proper education, the children “would also be inspired with a desire to improve their standards of living, and their parents through them. This in turn would give them confidence in their ability to make good and work shoulder to shoulder with the rest of us.”11 Draftenza saw the Métis, educated and healthy, as sharing in the future prosperity of the province.

Increasingly white citizens of Saskatchewan placed the responsibility for Métis rehabilitation on the provincial government. Prior to integrating Métis people into the social fabric of the province, white residents agreed that the Métis “standards of living” had to be improved. The strong tone and language of this letter reflects a simultaneous revulsion and fear of contamination, as well as a desire for the uplift and integration of Métis children. It was believed that education would prepare children for their role as future citizens and enable them to educate their parents about the Euro-Canadian ideals of cleanliness and proper living.

Community leaders among the Métis organized politically to address their position in rural society. The Métis Society was established in 1938 to address outstanding Métis land claims. Locals spread throughout the province to represent them. When it reported on the Métis Society in 1939, the Leader Post attributed Métis poverty to the early turn of the century when Métis had obtained scrip instead of treaties for their Indigenous title.12 The Métis Society argued, “Scrip issued at a time when land had so little value, and for the most part, as soon as this scrip was issued, it was bought up by rapacious speculators at prices that often amounted to little more than a few cents per acre.”13 Métis leaders acknowledged the precarious position of Métis in the province and sought to secure a land base similar to what had been obtained by the Alberta Métis for future generations. The society wrote to Métis politician and activist Joe Dion of Bonnyville, Alberta, and invited him to their convention in Saskatoon on 25–7 June 1940. Dion was a founding member, organizer, and president of the Métis Association of Alberta from 1932 to 1940. During this time the Métis successfully lobbied the Alberta government for an inquiry into the Métis lands issue in Alberta. The Ewing Commission was struck in 1936 and recommended the establishment of Métis colonies where they could become re-established on tracts of land held in common.14

To address the concerns of the Métis for land and livelihood, the Saskatchewan Liberal Party established the Métis settlement of Green Lake in 1940. The government Local Improvement District (LID), which administered areas without municipalities, operated the settlement.15 Green Lake’s remote location and proximity to the forest fringe enabled residents to combine agriculture with hunting, trapping, fishing, and animal husbandry.16 Initially, 100–150 Métis families had resided there, but the arrival of white settlers had left the Métis destitute. With the establishment of the colony, white settlers were bought out, and six townships were set aside for the exclusive use of the Métis. Families obtained forty-acre plots with ninety-nine-year leases that had title held by the Crown. Schools were established by Catholic sisters after a lay teacher could not be secured. Reporting on Green Lake, Commissioner G. Matte indicated that “this condition existed at Green Lake, but we were able to arrange with a certain RC [Roman Catholic] sisterhood to provide not only schooling but nursing and hygienic facilities as well, as the health condition of these people was very poor.”17 In addition, other community buildings were constructed, including a central farm, cannery, flourmill, and new homes. In 1941 Commissioner Matte was optimistic when he said, “This project is still in its infancy, but the co-operation given by the Métis people themselves augers [sic] well for success.”18 Provision for Métis education and health by the nuns meant government expenditures were minimal.

At the CCF Party Convention in 1944, the beginnings of a Métis policy took shape on two issues of concern for local white populations: the need for health care and for education of Métis peoples in Saskatchewan. Since municipalities were responsible for providing financial support for health care for those too poor to afford insurance, those municipalities with large Métis populations struggled. The CCF resolved to seek out an alternative arrangement where the province provided heath care for the Métis.19 First Nations people in the province had federally provided health and education and a constitutionally protected land base. Indigent Métis residents became the responsibility for rural municipalities, who issued relief and hospital cards.

Unsatisfied with long-range efforts to reform the Métis, municipalities with road allowance communities put political pressure on the government to remove and relocate the Métis. Local residents no longer had any need for Métis labour.20 In the late 1940s a growing chorus of citizen groups vocally demanded that the province assume responsibility for the care of the Métis.21 Another resolution passed by the Saskatchewan Rural Municipality (SARM) representatives requested that the government locate Métis in districts where they could become self-supporting from their own efforts and become responsible citizens. SARM delegates argued that the Métis should be a responsibility of the whole province, not a burden on a few municipalities. The resolution suggested that they could be self-sufficient if located in surroundings “natural to them,” or away from productive, agricultural lands coveted by white settlers.

Encouraged by the success of the formation of the Union of Saskatchewan Indians by Douglas and the CCF in 1945, the government hoped to replicate its success with the Métis. A conference was held 30 July 1946 in Regina to seek the input of provincial Métis groups on the future direction of Métis policy. Forty-two Métis representatives attended from across the province. Premier Douglas and Minister of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation O.W. Valleau were present on behalf of the government, as well as Department of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation (DSWR) bureaucrats J.S. White and K.F. Forster. The meeting was chaired by Morris Schumiatcher, who was also legal counsel for the Executive Council and a “trouble-shooter concerning Indian and Métis affairs.”22 Premier Douglas had requested that representatives of all Métis people gather in Regina to bring these issues to government attention. Chairman Morris C. Shumiatcher referred to Douglas’s success in bringing the Indian people together under the single voice of the Union of Saskatchewan Indians. He began, “Now the problems of the Métis are every bit as great as those of the Indians, if anything they are greater. You have all the white man’s problems and some of the Indian’s problems as well, so that together that makes a very formidable set of obstacles which must be overcome in order to bring to you a reasonably good share of the good things in life.”23 The policy of the government was to assist marginalized groups to obtain health, welfare, and education. The chairman explained that the government felt itself responsible to ensure that each segment of society had the same access to the “good things in life.” As well, it was hoped to create a single voice, as had been done for the Indian people, for all Métis in the province.

The negotiation between the political representatives of the Métis and the government took place through the Department of Social Welfare: “Our Department of Social Welfare hopes to be able to meet and consult with you, that together we may work out some method of assisting you with your problems. We do not believe in simple handouts, and we know that you do not believe in handouts of charity.”24 Prior to the meeting, the government had determined that the solution to Métis needs would be channelled through the Department of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation. While the stated intention was to assist in forming a Métis political organization, it was more likely that the department would introduce a policy for rehabilitating individual Métis rather than address political grievances. During the conference, those gathered heard the Métis policy take shape from Premier Douglas and Minister O.W. Valleau, the minister of social welfare.

The pressing issues for the meeting included the creation of a new Métis organization, welfare, education, health and veterans affairs. Addressing the crowd, Douglas stated, “We feel that the time has come now when we ought to face up to the whole problem of the Métis people, because of the fact the Métis people will affect other groups of people in the Province, and in particular communities where the Métis people live. Now that attitude of the government I can put in a very few simple words…. What we feel is that any group of people in our province, given an opportunity, given a proper chance, can do for themselves if only they are given a chance. In other words, our idea is not so much to help a group of people as to help them to help themselves.”25

This statement illustrates significant conflict about the government’s purpose and goals for the Métis. Nevertheless, the intended approach emphasized that the Métis would be integrated as individuals, not as a collective.

Many of the Métis from the agricultural communities came with suggestions for settlement and housing assistance from the government. Those in the northern areas sought to obtain reassurances that their communities would not be disturbed. While the intention was for the government to hear Métis input, Minister of Social Welfare Valleau indicated his lack of enthusiasm for a collective approach to resolving land issues: “I am not at all sure myself that the idea of group settlements is the wisest thing. You see you people are not a definite race apart. The ultimate solution will be absorption into the general population. I don’t think there is any doubt about that.”26 The government was unwilling to purchase land for the Métis. They aimed to assist with uplift, albeit ambiguously: “With your help we can give you people a certain pride in yourselves, and you can’t have that pride in yourselves until you are really proud of yourselves.”27 There was much disagreement throughout the conference amongst the Métis about the future of the provincial organization; however, many agreed about the need for secure land. Their historic experience of dislocation proved the value of a secure land base. The meeting ended without a clear articulation of the issues or their solutions.

The ongoing and conflicted public outcry for government intervention stimulated an interprovincial meeting to find a solution. Chaired by J.H. Sturdy, Saskatchewan’s minister of health and welfare (who had replaced Valleau after the election in 1948), the government hosted an interprovincial conference to seek out possible solutions to the Métis situation. Inviting other welfare directors from Prairie provinces, Sturdy outlined his view of the problem, saying that the Métis fell “short of the economic and cultural level of the white population” and accordingly had “a higher incidence of illiteracy, destitution, illegitimacy and other social problems.”28 He believed that their living standards and “cultural level” needed to be improved. He believed that they misused family allowances and public assistance by not purchasing the proper foods and essentials and condemned Métis parents for failing to seek regular employment. He recognized that the growth of mechanical farming had eliminated much of the need for farm labour, and that many of the communities were isolated from employment opportunities. Finally, Minister Sturdy lamented that, despite the assistance being given to the Métis, the situation was worsening.29

The conference recommended approaching Métis and Indian rehabilitation with the assistance of the federal government.30 Difficulties faced by Indigenous residents of the province were seen primarily as lack of adjustment to the Euro-Canadian nuclear family model and the inability to integrate into the modernizing economy and society in the West.31 Not surprisingly, the solution was increasing social welfare interventions. While the long-term plan to address the growing social distance between white and Indigenous communities in the province was a comprehensive, federally supported Indian and Métis welfare response, the provincial government moved forward with its program of rehabilitation and relocation.

The term rehabilitation was increasingly employed by CCF officials to describe the process by which the Métis people would embrace the value system of the surrounding Euro-Canadian settler communities and cease to require government assistance and support. After the Second World War there was renewed interest in resource development and government intervention, particularly in the north, which led to fundamental changes to the Indigenous fur and fishing economy. This tension led to what one observer termed a confused and turbulent contact zone. The primary outcome was family breakdown and intergenerational conflict.32 In the south, poverty and loss of land had pushed the Métis into a tenuous existence dependent on seasonal employment and government relief. From the point of view of government officials, the high birth rate exacerbated these problems. “It would appear that this process of change is giving rise to a problem from the point of view of the government in that budgetary appropriations on behalf of these people have increased in recent years.”33 Government rehabilitation policy, established in the early years of the CCF government, strove toward “the gradual integration under which the Métis ultimately are encouraged to develop into a mature, independent and self-sufficient group of people able to conduct their own enterprises and to solve their particular problems without excessive reference to government or other agencies.”34 Rehabilitation sought to educate Métis families to adopt the work ethic, dress, language, land tenure, aspirations, family structure, and political outlook of the majority Anglo-Canadian Saskatchewan residents. The virulent racism that flourished among the settler population in the post-war period was left unaddressed and unacknowledged.35

Tenets of the Social Gospel and moral purity were deeply embedded within the social and political identity of Tommy Douglas and the CCF party. During the CCF years in power, the state shaped the subjectivities of provincial citizens through the aegis of reform efforts in education and modernization of social welfare programs.36 While, unlike Indian wards of the federal government, the Métis did not experience a distinctive legal regime dictating their relationship to the state, integration came through the legal and political structure of the province.37 As Joan Sangster points out, “Even if ‘race’ as a legal category was not articulated in Canadian statues, racist ideology and operations resonated through the articulation of the law.”38 That Métis children went from being a fraction of the child welfare cases to the predominant number over the two decades under discussion illustrates how welfare legislation was articulated in the lives of Métis women and children.

Many of Tommy Douglas’s accomplishments as premier of Saskatchewan and an MP in Parliament have been well documented. In fact, Canadians voted Douglas the greatest Canadian of all time, over Terry Fox, Pierre Trudeau, and Frederick Banting in a 2004 CBC poll.39 However, there is a dearth of information in standard biographies on relations with First Nations and Métis peoples. The traditional historical accounts of the CCF and biographies of Douglas lack meaningful analysis of his view on Native issues. With the exception of Laurie Barron’s Walking in Indian Moccasins, a book devoted explicitly to these policies, biographers have focused their discussion of Indian Affairs and Métis issue to a few paragraphs, with special mention of Douglas being made honorary chief, We-a-ga-sha, in 1945.40

Several historic events shaped Douglas’s intellectual, spiritual, and political development.41 The widespread and indiscriminate devastation of the Depression on the Prairies played a critical role in his reformist outlook. According to biographers McLeod and McLeod, “The spectre of poverty, in the city and in the countryside, challenged the youthful pastor to rededicate himself to the social gospel.”42 Douglas followed a route similar route to that of J.S. Woodsworth, his intellectual and political mentor, mixing ministry with sociological inquiry, eventually abandoning both for provincial and national politics.43

Another impact of the Depression on Douglas was his advocacy of eugenic solutions, most notably in his MA thesis.44 Biographers have explained this anomaly as further evidence of Douglas’s faith in the role of the expert and as part of a misdirected but not uncommon belief in the pseudo-scientific promise of eugenics in the interwar period.45 When Nazi Germany began to sterilize its opponents, many on the Left grew disillusioned with eugenics. Douglas came to realize that the Nuremburg Race Laws of 1935 led to the slaughter of millions in Eastern Europe, and he dropped his support for eugenics. As evidence of his disavowal of eugenic solutions, while premier, Douglas soundly rejected any attempt to initiate eugenics as part of the public health-care system.46 Unlike Alberta and British Columbia, Saskatchewan did not politically or legally develop sterilization laws targeting specific populations.47 Douglas and the CCF embraced a social rather than biological solution to criminality and illegitimacy, out of their left-of-centre belief in government involvement in the conduct and reform of society.48

Tommy Douglas (R-A57294)

Even though Douglas’s master’s thesis in sociology from McMaster University, “The Problems of the Subnormal Family,” did propose eugenic solutions, it was interested primarily in sociological interventions.49 The disorderly “subnormal families,” according to Douglas, had a detrimental impact on the local community and society in general.

While the families that Douglas studied were non-Indigenous, his overall recommendations to rehabilitate the “subnormal” class bore a striking resemblance to early CCF Métis policy. Because of the apparent danger of “subnormals” to the surrounding community and their ongoing need for financial support, Douglas argued that this class should legitimately be subject to the intervention and regulation of the state. For Douglas and other social reformers, first, in order to be disciplined, the “subnormals” would have to be represented. This legitimized the invasive surveys and intellectual queries into the private lives of citizens.50 Through his voyeuristic enumeration of the impoverished residents in Weyburn, Saskatchewan, Douglas shared an outlook similar to that of other middle-class reformer men who ventured into the working-class areas and homes in the name of scholarship or social intervention. In later years, many dispossessed and impoverished Métis people fit the criteria Douglas utilized to categorize those who were “subnormal.” Surveys were conducted among the Métis to obtain demographic and personal information.

According to Douglas, “The subnormal family presents the most appalling of all family problems.”51 In addition to containing members who appeared mentally deficient, families were seen as falling below accepted moral standards, “subject to social disease, and finally so improvident as to be a public charge.”52 Douglas proposed a new solution for the social worker, legislator, and educator “to a problem long neglected, too long placed in the category of unmentionables.”53 Douglas’s concerns hinged on the unbridled sexuality and perceived irresponsible reproduction of the women, the evidence of which was their large families. “Surely the policy of allowing the subnormal family to bring into the world large numbers of individuals to fill our jails and mental institutions, and to live upon charity, is one of consummate folly,”54 Douglas lamented. Not only was the impact felt in the economic cost to society, but also in the contamination of the surrounding “normal” community. Having the “subnormal” live amongst the normal led to three interrelated social outcomes with which Douglas was concerned. First was the danger of sexual and medical contamination.55 Second, there was a degeneration of academic standards in the classrooms, where he feared that “a large number of subnormal children in the community cannot but have a detrimental effect on the mental standards and intellectual attainments of the community.”56 Finally, there were the moral effects of the female “sexual delinquents” who were responsible for lowering the moral standards of those they contacted. Unlike the “normal” young women, these women lacked a sense of shame for unwed pregnancies, clear evidence according to the thinking of the time that they were mentally defective. “At the same time some of these girls become illegal mothers and much of the stigma has been removed.”57 The high economic needs of the “subnormal family” increased the taxes for the whole community through expenses of medical bills, dental bills, charity, and education. With their children cared for in orphanages or on relief, Douglas stated, “Instead of having the upkeep of 12 women, the city now has the cost of 175 individuals on its hands.”58 Douglas focused his attention on women’s reproductive abilities and their moral guidance/instruction within their families. On both counts, he judged the women harshly and deficiently, while he demonstrated they were a clear threat to provincial society.

The environment was implicated in the moral state of the families. However, Douglas was at a loss on whether it was the cause or the effect. Moral and physical qualities intertwined in the “filth, squalor and unwholesome conditions.” For example, “Case no. 1 where two entire families are living in a three room shack. Privacy is of course impossible, and despite the fact that the children are normal, there are unmistakable signs of moral degeneration, because of the home influence.”59 The subnormal social environment encouraged the lack of adherence to decent moral codes accepted in the larger society as the families in general “seem to have no feeling of shame.” He was especially critical of unwed mothers, since “the girls who have given birth to illegitimate offspring have in the main refused to part with them, and seem to feel no compunction about the censure of society.”60 Among middle- and working-class families, intense shame at illegitimate offspring reflected the “proper” moral sensibilities. Unwed mothers in working- and middle-class families in this period often gave birth in maternity homes and relinquished children for adoption to avoid the stigma of being a “fallen woman.”61 According to Douglas, maintaining the shame of unwed pregnancy was an essential component of regulating women’s sexuality and an aspect of moral citizenship.

Douglas’s final chapter spelled out his formula to address the problem of the subnormal family. He posited a new role for the state assisted by the churches: rehabilitation. Families deemed by officials to be subnormal would be compelled to embrace the values of the majority society through law, education, and moral reform. He argued, “Since the state has the problem of legislating in the best interests of society, and since we have seen that the subnormal family is an ever increasing menace physically, mentally and morally, to say nothing of a constantly rising expense, it is surely the duty of the state to meet this problem.”62 Douglas proposed the improvement of marriage laws, articulated a policy of segregation for those deemed “subnormal,” and proposed the sterilization of the unfit while providing increased knowledge of birth control.

Douglas was interested primarily in social segregation: relocating the “subnormal” class where the physical, mental, and moral effects listed would no longer contaminate the normal community. He claimed, “There can be little doubt that this group exercise an influence that is detrimental and which could be best removed by segregating them.”63 Men who were able to work but lacked initiative should be placed on state farms or colonies where competent supervisors could make decisions for them. Similarly, Douglas recommended, “With proper supervision the women could become better housewives and better managers of family finance.” In addition, separate schools with specialized curriculums should be developed that would isolate students from contaminating other children, while teaching them useful skills.64

This treatise on the potential for the state to rehabilitate the “subnormal” contains substantial interest in moral and gender rehabilitation. Unlike earlier periods, when the state looked to churches and private charities to effect the work of moral regeneration, Douglas envisioned, then enacted, a colony regime directed by social welfare experts to assimilate Métis peoples. In interviews in the late forties he still utilized terms like subnormal to describe impoverished, under-educated groups of Saskatchewan residents. It was hoped that Métis subjectivities – that is the living standards, family structure, hygiene practices, kinship patterns, and educational and economic aspirations – would be refashioned to facilitate absorption into the surrounding settler communities by embracing the moral standards of Euro-Canadians.65 Utilizing the early colony schemes and rehabilitation policies, the state attempted to bring about the moral regulation of Métis families in reproduction and proper gender roles.66 According to Mariana Valverde, “Moral regulation was an important aspect to ruling, helping to constitute class, gender, sexual and race relations by interpreting both social action and individual identity as fundamentally ethical.”67 Tommy Douglas, as progressive reformer, embraced the opportunity to employ his rehabilitation strategy once he became premier and was supported by rural municipalities who sought government solutions to their economic burdens. This approach overlooked such complexities as the long-standing issues of land loss, race, and the complicity of the surrounding white communities in the economic marginalization of Métis families.

The CCF began relocating Métis road allowance families as early as 1947.68 Green Lake, the previous Patterson government experiment, became the destination of several relocated Métis families from communities around the province.69 Henry Pelletier was married and working at the time of the relocation and recalled the promise of forty acres, assistance in setting up farms, and relief to live on until they were able to clear the land. Henry recalled that as the family and community waited for the train to arrive, they looked back to see their homes on fire.70

Other Métis experienced having homes burnt and the disappointment when they arrived at the new community. Métis leaders Jim Sinclair and Jim Durocher saw relocations as a way to rid white communities of the embarrassing reminder of their intolerance:

Again to help us, but really to clear the land of our people. Try to shift us where no one was and they had the old Green Lake project, of which they shipped our people in trains, not in trains, in boxcars in 1947. I think in ’46 and ’47. They moved all our little belongings into the boxcars. I remember that as a boy and one of the things that really bothered me and it still bothers me today, our people lived in tar paper shacks, you know and very little shelter, and as these people left their community with all their stuff piled on their wagons and chairs and the little bit they had, the houses were purposely set on fire as they were leaving, as if to say it to them, these people “Don’t ever come back here again.” And that was done at Crescent Lake, that was done in Lestock, and it was done in other communities. And as I, as I met with other half-breeds a few years later they had the same experiences. So again, it was, you know, people speak about the Holocaust for the Jews. Well, it was much the same for us in terms of trying to drive us from one place to another. And it was difficult for us, and it wasn’t very long ’till most of those people just made their way back to Regina. And then we set up a tent city, then we start moving into the nuisance grounds around Regina where all the half-breeds lived, and then we had tent cities, and then people would come in there with their cars and trucks at night and run over people’s tents, you know, drive people out.71

Jim Sinclair felt the reason the government moved the Métis was that they were a political embarrassment: “I don’t think it was the farmers so much. I think it was just the embarrassment to the government of Saskatchewan at that time and of course their philosophy of hoping to find us a better life, which never really was the issue. It was to get rid of us and put us in the North. Whether we survived or not, they didn’t care.”72 They attempted to hide the shame of Métis poverty and marginalization by relocation to the north. “Just hide us wherever they could and hide their shame for the way they were treating the half-breeds and to keep our rights, sort of under the rug and to hope that we would never organize. And I think the worse they treated us the more we became aware of what was happening, and the more we became aware of what had to be done to move ourselves into a position to be part of Canada.”73 The relocation and rehabilitation of Métis road allowance communities after 1947 was one facet of the early CCF Métis policy.

Oral histories collected by the Gabriel Dumont Institute from Métis elders provide a narrative of the interconnection between relocation policies and the Green Lake children’s shelter. Green Lake resident Peter Bishop was a child during the 1940s. He recalled the Green Lake shelter and the arrivals from the Métis resettlement program:

They had a couple of shelters there for mostly Métis kids from southern Saskatchewan. They were shipped there and they were looked after by the government. They had set up those houses. In fact there’s one building that’s still standing up there. That’s the old Alec Bishop Childcare Centre. That’s one of the shelters. And they had shipped a bunch of Métis, I think it was the late 1940s early ’50s from all over southern Saskatchewan. Yeah. These are the road allowance people that Nora’s talking about. Glen Mary and Duck Lake? Glen Mary, yes. And Kinistino. Baljennie – all those places. That’s where these people came from. Okay? They arrived in the spring and they stored most of the furniture in the church. It was an only church by where we lived. My Dad gave them permission. And they lived in tents because right away, soon as they moved to Green Lake, they had to walk to the bush to cut logs so they could build their own homes for the winter, before the winter set in. And it was the local people that helped them, because they didn’t know how. My dad was one of them. And what was sad, particularly sad about the children that came with them, they’d never gone to school. They weren’t allowed. See a lot of the road allowance people lived close to Indian reserves. The Indians wouldn’t allow them in their schools, so they never went to school.74

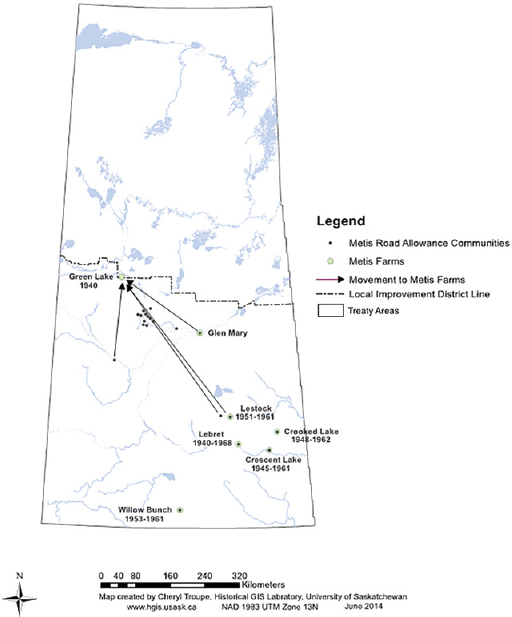

Métis Road Allowance Communities, Saskatchewan, ca. 1940

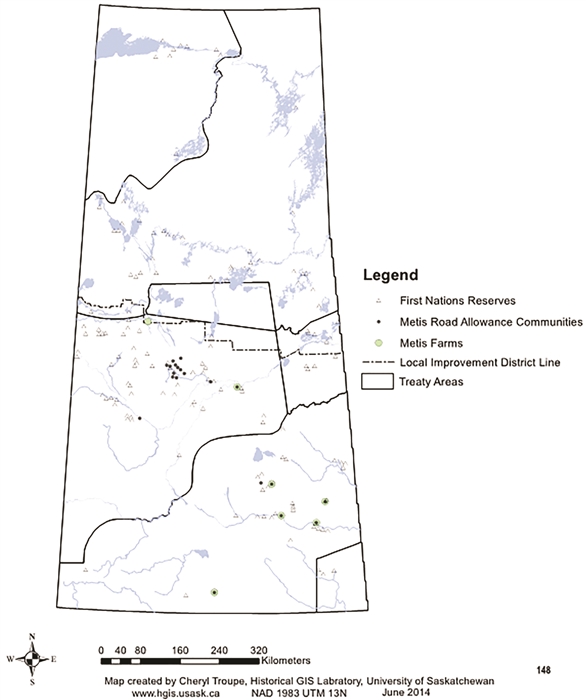

Métis Road Allowance Communities and First Nations Reserves, Saskatchewan, ca. 1940

Another former resident of the Lestock road allowance, Isadore Pelletier, a Métis elder who experienced relocation as a child, shared his memories of being moved from Lestock to Green Lake. He and his family lived on a road allowance community called the Chicago line, ten miles from Lestock. The men worked for farmers during summer months. They picked roots, helped with threshing, and chopped bush. Isadore recalled, “My dad would always make enough for 10 bags of flour. We’d be all right. Make it through the winter, we’d hunt deer and trap mink and muskrats, eat turnips and potatoes from the garden. My job was to start the fire, then go out to feed and water the horses.”75 The seasonal wage labour that was supplemented with hunting and trapping provided the family with an adequate living.

During the relocation, the family arrived in Meadow Lake, then Green Lake, where Isadore recalled the family received a cool welcome. The new arrivals placed additional strain on dwindling resources and job opportunities in Green Lake. Isadore felt, “They [Green Lake residents] resented us. Children had problems in the school. And it seemed even there, it was ‘just like we always were.’”76 Gradually the relocated Métis began to leave, since it appeared that there was not enough to make a living there. He remembered feeling bad for his community: “We made it back but all the way back, we were harassed.”77 It was the recommendation of a local Métis leader in Lebret, L—— who was working for the CCF government that led the local Métis to embrace the relocation to Green Lake as a new opportunity for future prosperity. He recalled the reasons the community were given: “We were living in squalor, children not going to school. Those were some of the reasons they gave.” Upon returning to Lestock, the family found that there was nothing left and went to Regina. Isadore remembered fondly, “It was such a tight community. We had self-government. That was what we had, and it was good.”78

Premier Douglas, who certainly intellectually and politically supported if not initiated the relocation and segregation of the Métis, faced criticism for the outcome of the relocations from opposition MLAs. Defensive of the government’s Métis policy, Douglas replied to the opposition criticism from Vic DeShaye, Liberal MLA for the Melville riding:

For some time the DSW has been working on a program for re-establishing the Métis on a self-supporting basis and has been doing so in cooperation with the several municipalities where they are located. However, in view of your comments in the legislature on Thurs March 2, I would take it that you are opposed to moving these people from the road allowances and re-establishing them in areas where they can become self-supporting citizens. It is difficult for me to see how you can oppose that action of the government in moving these people when you are speaking in the legislature then write to me privately to ask what we are going to go about moving them. It is about time you made up your mind whether you are anxious to have these people rehabilitated or whether you are merely concerned with making political capital out of the situation.

I don’t think that municipalities will take very kindly to the fact that the first time any constructive steps were taken to re-establish the Métis you did everything possible to have this action by the government misrepresented and misunderstood. I shall make it my business at my earliest opportunity to acquaint the municipalities in question with the stand which you have taken in the legislature as opposed to the concern which your letter shows for the difficult position in which the municipalities find themselves in connection with the Métis problem.79

In response, DeShaye reiterated the point that the relocation policy challenged the CCF image of a humane and just political alternative in its treatment of the Métis people. He replied, “If you will read the transcript of my speech you will see that what I criticized was not the movement of the Métis to Green Lake, but the failure to provide an adequate program and accommodation for them at Green Lake. The delegation that saw me said that they had to move away from Green Lake because they and their families had only tents to live in, and no accommodation was being made available for them for winter. Then when some returned to find their homes burnt they became a greater responsibility than before.”80

The attempt to craft a Métis policy based on relocation and rehabilitation left the Métis further impoverished and at the mercy of municipalities. The financial commitment required to adequately re-establish and rehabilitate Métis at the Green Lake Métis colony was never in place, and Douglas’s vision of the relocations and rehabilitation merely removed road allowance families and cast them adrift in the province.81 In addition to Green Lake, the CCF government operated experimental farm colonies at Lebret and Willow Bunch, and smaller colonies at Crescent Lake, Baljennie, Crooked Lake, Duck Lake, and Glen Mary (see map and appendix).82

The implementation and outcomes of the relocation and rehabilitation policies at Green Lake and elsewhere received mixed reviews. In 1953 D.F. Symington, a Saskatchewan conservation officer, amateur ethnographer, and author, extoled the benefits of the CCF policy of relocation and rehabilitation. His “Métis Rehabilitation” in Canadian Geographer offered readers visual contrasts between the old and the new policies. He emphasized that rehabilitation held great promise for the Métis, whom he termed “a group that can be considered the west’s forgotten minority.”83 Like others, he believed that the 850 Métis in Green Lake were in the midst of an economic and social revolution from extremely primitive to modern living. Until the government intervened, the Métis had “been gypsy-like, untrained and unwilling to work, despised by and despising the prosperous white man.”84 He stated, “Rehabilitation must take into consideration the traits and peculiarities of the Métis as a cultural group and as individuals, such as the Métis tendency to stress the value of personal enjoyment on a day to day basis, material possessions to be valued as they add to the enjoyment, discarded as they become a burden.”85 The goal of rehabilitation was to raise the standard of living in community. “In other words he had to make them wish to work.”86 Unlike the white settlers, who needed to work in order to eat, the Indigenous people “have never needed to work in order to exist, and had no such incentive.”87 Eliminating the seasonal cycles of living off the land ensured that by necessity the Métis would embrace subsistence agriculture, wage labour, or both.

According to this early publication, the relocated Métis from the southern road allowance communities brought a twofold benefit to the Green Lake community: they brought “new blood into the Green Lake settlement, where for two centuries the dozen major families had been intermarrying,”88 and the relocated Métis had depended on social aid, living in shacks on road allowances, and by contrast in Green Lake, they had been given lumber by the government. For those who remained to build, “There are now none without board floors and roofs, and the unutterable filth of a decade ago has been replaced by something approaching cleanliness.”89 The writer failed to mention the large percentage of families who chose to leave rather than remain in Green Lake. The rehabilitation envisaged through farming plots would bring the Métis what had eluded them as seasonal trappers and hunters: a notion of private property and elimination of mobility. Symington claimed that, in “tying themselves to plots of land, they are beginning to look on their plots as their own.”90 Finally, rehabilitation included the education of Métis children. The next phase in the rehabilitation of the Métis would focus on Métis women in order to inculcate proper notions of morality by rehabilitating Métis views of illegitimacy. Symington observed, “Most of them remain amoral, and illegitimacy occasions no stigma.”91 Like the “subnormals” of Douglas’s master’s thesis, according to Symington the Métis lacked the sentiment of shame attached to unwed motherhood.

In response to fallout from the failed CCF Métis policy, a new partnership was struck. In 1955 the Local Improvement District, the government branch responsible for the administration of the Green Lake Settlement, and the Department of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation began to work together to solve the “Métis problem” in Green Lake. Together, government bureaucrats began to develop a new direction in Métis policy, bringing the expertise of social workers and social welfare professionals into Métis policies in a new fashion. Like elsewhere in Canada, a “welfare economy” was beginning to emerge, as the expansion of settlement and fishing and game restrictions reduced subsistence hunting and gathering, and growing industrial activities gave preference to white male labourers over Indigenous.92 Despite officials’ belief that their involvement would be temporary, the welfare state expanded exponentially after 1950, as did Indigenous poverty.93