5

Post-War Liberal Citizenship and the Colonization of Indigenous Kinship

Rational-secular social scientific solutions to the “Indian problem” proposed interventions to adjust the perceived problematic subjectivity of “the Indian.” As Hugh Shewell has pointed out, social scientists in anthropology, sociology, and psychology turned increasing attention to the studying the acculturation, or lack thereof, of Indigenous peoples.1 Anthropologists increasingly shifted attention from salvage ethnographies to cultural anthropology and community studies to determine various levels of conservatism and acculturation, and the processes by which individuals and groups retained or discarded Indigenous traditions.2 As racial theories of difference fell out of favour, support for alternative approaches to Indigenous assimilation and integration gained traction following the publication of Dr Moore’s malnutrition study in 1948 in the Canadian Medical Association Journal. After conducting research on Indian people during the Second World War, he found that what had been formerly understood as racial characteristics, such as “shiftlessness” and “indolence,” could be the result of chronic fatigue stemming from malnutrition.3 This shift away from racial explanations stimulated further study in the search for an alternate explanation for Indian people’s lack of interest in assimilation.

In the 1940s attention turned to the earliest socialization of Indigenous children in their families as the possible origin of psychological difference of tribal peoples. Dr Bartlett, a physician from Favourable Lake, Ontario, in a letter to the Indian Affairs Branch, suggested early socialization might provide an alternative explanation for Indigenous people’s lack of interest in assimilation, different from the findings of the malnutrition survey. Bartlett echoed missionaries from an earlier era who saw lax parenting as the sources of Indigenous resistance to Euro-Canadian assimilation attempts.4 Bartlett contrasted the absence of corporal discipline of children to an unstated, but assumed, strict disciplinary regime of white parents and concluded that this was the origin of what Bartlett and presumably others perceived to be a lack of responsibility. He claimed that, as adults, Indigenous peoples retained these

childhood patterns, and I suggest that they have persisted into adulthood because at no period in his life was he taught to disregard them and adopt adult thinking and discipline.

In support of this we have the observation that Indians who have been brought up in a better environment, e.g.: a good school under a good teacher, who tried to do more than teach reading and writing, usually show more initiative, and usually have more sense of responsibility towards other people than do Indians raised entirely in native ways.5

Perhaps there is no apparent connection to Dr Bartlett’s prescriptive letter and the subsequent Indigenous child removal policies that began in earnest in the 1960s, but it nonetheless suggests a long-held belief of the detrimental effect of the Indigenous family on children, and more importantly, on Indigenous assimilation.

Taking this approach to the next logical step, Marcel Rioux, a cultural anthropologist at the National Museum in Ottawa, studied social customs of the Iroquois at the Six Nations Reserve near Brantford. For his research on family life and social development, he composed an extensive and invasive questionnaire on child-rearing practices. Anthropologists with new academic interest in the intimate lives of Indian families had no misgivings about asking highly personal questions, such as “Question 14. Does the couple continue to have intercourse?” listed under the heading “Prenatal Period,” and “Question 47. Is there much attention shown to the baby?” followed by “Question 48. How is he nursed? Breast or bottle fed?”6 While the results of these questions remain unknown, it reveals greater intrusion into the lives of Indigenous peoples, thought to be powerless subjects trapped in government-controlled laboratories, in the paternalistic search for the elusive answer to the problem of assimilation.

The subjects of this particular study, the Mohawk of Brantford, strenuously objected to having researchers pry into their intimate lives. Mrs Farmer, a representative of the Local Council of Women in Brantford, wrote a letter of protest to Ross Macdonald, Speaker of the House of Commons, stating their displeasure. In a rare and candid response, the government stated that this study would help to uncover and eradicate “sources of maladjustments.” A full investigation of “intimate” behaviour was necessary in order to arrive at a “full understanding” of a given society. In a conclusion that must have given the Mohawk women even further cause for concern, the government suggested that the study had been modelled after a Peabody Museum Study of the Navaho, and that as a result of this study, the Navaho “will in the near future be completely integrated into the active life of the county with their complete consent and satisfaction.”7 In short, the government felt that researchers needed to pry into areas of family life deemed private by Indigenous people. This biopolitical intrusion into the intimate family setting to secure Indigenous integration reflected a newly emerging settler-colonial logic that linked social scientific knowledge of the Indigenous family life to state efforts of elimination.

Several factors led to a revision of Indian legislation in the immediate post-war period. The Special Joint Committee of the Senate and the House of Commons to Consider and Examine the Indian Act (SJCSHC) sat from 1946 to 1948. For the first time since Confederation, Indigenous leaders from across Canada were invited to present their views on the policies of the department and conditions on reserves.8 The joint committee considered a wide range of areas, including provisions for Indian status, band membership, schooling, taxation, land rights, treaties, and governance on reserves, including band membership and provision of child welfare services. In part, the hearings came in recognition of Indigenous demands for increased self-determination and legal recognition. Decades of Indigenous political organizing for improved recognition of Indigenous rights and unprecedented service in the armed forces during the Second World War created a politicized pan-Indian awareness of the infringement of Indigenous, treaty, and human rights. Likewise, non-Indigenous Canadians had become acutely aware and discomfited by the injustices of the Indian Act system.

The other impetus for reform came from the government belief that the changes would lead Indigenous peoples to embrace modern industrial society and provide the necessary preparation for the voluntary adoption of future Canadian citizenship. From the outset, the objective was elimination of the Indian people, or, as Duncan Campbell Scott put it bluntly in 1920, “to continue until there is not a single Indian in Canada that has not been absorbed into the body politic, and there is no Indian question, and no Indian Department.”9 A modernized policy of “integration” enabled Indian people to retain aspects of their culture, while the Indian Act provided the legislative framework to assist Indigenous peoples to embrace the liberal political and social values presumably held by mainstream non-Native Canadians. As historian John Leslie has pointed out, the immediate post-war period is one of historical importance to the study of Canadian Indian policy, as it provides a historical bridge between the earlier protectionist era and the new integrationist era.10

The joint submission of the Canadian Welfare Council (CWC) and the Canadian Association of Social Workers (CASW) to the committee identified the critical role that could be played by social work professionals with their expertise in working with immigrants and families in crisis. The CWC and CASW mapped out a new role for social welfare experts and the helping services of professional social scientists in solving the Indian problem. The submission stated, “In our judgment, the only defensible goal for a national program must be the full assimilation of Indians into Canadian life, which involves not only their admission to full citizenship, but the right and opportunity for them to participate freely with other citizens in all community affairs.”11 The definition of integration and assimilation for these social welfare experts meant that Indians would no longer be relegated to receiving second-rate services from voluntary organizations and Indian agents. Instead, they would be joining the rest of Canada as fellow citizens in embracing the therapeutic ministrations of professionals, whether they be social workers, doctors, or educators.

In documenting the vast discrepancy between white and Indian communities in social indicators like tuberculosis, infant mortality, educational levels, and housing, the CWC and CASW attributed them to the state of dependence Indian people had been forced to endure as a result of their protected status. They supported full citizenship rights for Indian people since they had demonstrated their willingness to participate in the two world wars.12 While offering commentary on aspects of Indian policy such as social conditions, education and health, and acknowledging the interrelationship between all three of these areas, social work professionals believed that social issues were most pressing and the area where the CASW and CWC could offer support. The problems identified as stemming from a lack of properly administered services included prostitution, venereal disease and unwed pregnancy, juvenile delinquency, the prevalence of Indigenous adoption, and the legal barriers the Indian Act erected between Indian mothers and their children with non-Indian fathers. The brief concluded, “Owing to the fact that the wards of the Dominion Government are not eligible for benefits under provincial legislation, Indian children who are neglected lack the protection afforded under social legislation available to children in white communities.”13

Social workers sought to bring enlightened adoption practice to Indian children to provide them with what was believed to be the protection of years of accumulated professional expertise. Likewise, the submission pointed out the injustice of separating women and children from Indian families (through status legislation) as fundamentally problematic and abnormal.

The submission argued for the coordination of federal and provincial relations and the development social services on reserves. Critical of the outdated residential school system that perpetuated the breakdown of families, professional social workers attempted to modernize Indian policy to bring new knowledge and methodologies of family services to bear in Indian communities. Like orphanages, which had been abandoned in white society, it was felt that residential schools could not socialize children properly for the modern Canadian nation state. The joint submission recognized “that no institution is an adequate substitute for normal family life. We believe that foster home service should be developed within the Indian setting.”14 “Normal family life” – the idealized family life with a two-parent nuclear family – was profoundly racialized and gendered and did not reflect the realities or aspirations of Indigenous peoples. It was widely recognized that the schools were responsible for more than educating children and were used largely for orphaned and neglected children. The submission further recommended ending residential schools and bringing Indigenous peoples under the purview of provincial welfare agencies.15 According to Children’s Aid Societies and the Department of Child Welfare, Indian children could obtain “proper nurture” (Euro-Canadian) in a family-based setting like other neglected and dependent future citizens.

Based on the recommendation of the CWC and CASW and others, the revised Indian Act recommitted policy for the eventual integration of Indian people. However, Indian people would now play a role in helping themselves advance. The revised Indian Act brought Indian people across Canada under the scope of the provincial laws, via section 88, paving the way for provinces to provide educational, health, and welfare services.16 With this, the newly understood “Indian problem” was no longer viewed through racial theories of physiological difference or social evolution. In the post-war period, psychological explanations for difference arose. An Indian Affairs circular asked,

What is this so-called “Indian problem”? In essence it is this: The Indian is too often considered an outsider in our society. His reserve is palisaded with psychological barriers which have prevented close social and economic contact between Indian and non-Indian. It is the policy of the government to help the Indian, caught in an age of transition, to adapt himself to a larger and more complex society, to be able to earn a living within that society if he wishes to do so. But there are many factors which inhibit the Indian in his adaptation to a mid-twentieth century technological world. Most are but dimly understood.17

Indian Affairs effectively recast the barriers faced by Indian people, from external barriers such as the legislation preventing Indians from leaving the reserve or from non-Indians coming onto the reserve, into a collective psychological inferiority complex. The role of social welfare experts would be to help break down the internal “psychological barriers” and to bring to light the “dimly understood” factors that prevented Indian people from embracing the allegedly superior modern world.

The Indian Act, 1951, in addition to allowing provincial laws to be applicable on reserves, also expanded the enfranchisement section and altered the section on Indian status. Indian women who married out and their children were further disadvantaged. However, women obtained the right to vote in band elections for the first time. Section 11, devoted to stipulating who could claim Indian status in Canada for the purpose of the Indian Act, placed much greater emphasis on the male line of descent and the legitimacy of children. Because of the ambiguity around the Frances T—— case cited in chapter 2, the section detailing children’s status clarified that adopted children could not claim Indian status.18 The 1869 Indian Act amplified gender discrimination to determine who could claim Indian status and political rights. However, the 1951 revisions further stipulated that women who “married out” were now automatically deprived of Indian status and band rights from the date of their marriage. Children were also enfranchised along with their mother and no longer entitled to live on a reserve, and property that women may have owned was sold by the superintendent, and they were given the proceeds.19 Previously, women who married a non-Indian had ceased to be Indian but were able to retain their treaty annuities and community membership. Likewise, illegitimate children were placed in a precarious position, unable to claim Indian status from their mothers.

Child welfare experts quickly understood the implications of these changes when reviewing the proposed legislative changes. In March 1951 Reg Davis, executive director of the Canadian Welfare Council, pointed out, “While Indians now must conform to all laws of general application from time to time in force in any province, he should also have the rights of any provincial citizen regarding will, maintenance of children etc.”20 The key difference between federal legislation and provincial child welfare legislation lay in the legal relationship between mothers and illegitimate children:

The same point arises in regard to illegitimate children (s.11 9e). An unmarried mother is the legal guardian of her child, and yet this act would have the effect of depriving the child of that guardianship if his father is not an Indian, and preventing the child from being brought up on the reserve by his mother. This guardianship is recognized in regard to inheritance (s.48) (13) but it is much more important that the child should have the care of his mother than any money she may leave. The mother should be allowed to give that care on the reserve, if that seems desirable to her.21

The director also had noticed that there had been no clear policy regarding the extension of social welfare services on reserves. Davis replied that there were reports from provincial child welfare workers of the practice of removing illegitimate children from mothers by officials employed by Indian Affairs. In addition, adoption of these children who lacked Indian status could not take place since the legislation stipulated that only legitimate children were accorded Indian status. He further elaborated on his original letter:

We have been informed by child welfare workers that there is often real difficulty in arranging for a child whose mother is Indian and whose father is white to be brought up by his mother on reserve. There seems to be a tendency on the part of officials to think that it is preferable for him to be removed from his mother…, The proposed Bill makes it socially difficult for the mother to act as a guardian of the child, although legally she has that right. The child, who is technically not an Indian would be on the reserve only on sufferance and not by right.22

As Davis could see, the legal and social limbo of Indian children of unwed mothers made it impossible for them to be adopted into Indian families, and they were unlikely to be adopted into white families as a result of the racial attitudes toward Indigenous people in Canada. This passage also implies that children of unwed mothers were routinely removed by “officials.” The legislation consequently further marginalized Indigenous mothers and children.23

Also, while enabling the extension of provincial law on reserves, the bill failed to secure a role for Indigenous communities to participate in developing culturally relevant services – which Davis pointed out should be the goal of any progressive change in the law: “We should also like to see welfare services combined with health as among the items for which bands may take some responsibility…. We assume that Indians like other people learn to take responsibility by having it given to them, and if the financial assistance were accompanied by education, individual counselling, as it is available in some of the provinces, we predict that the Indians would need less and less supervision in such matters.”24

The revised Indian Act was passed on 17 May 1951 without the suggested changes.

Without clear direction on child welfare and with no resolution of the impact of gendered discrimination, social welfare developed slowly and unevenly. As Jessa Chupik-Hall has concluded, child welfare services to Indian people evolved into a “patchwork” of residential schools as child welfare institutions, foster homes on reserves, community development, and removal of women and children.25 In English-speaking Canada, the movement away from institutional methods of providing for the indigent and abandoned children – or in the case of Indigenous populations, residential schooling – came about as a result of new methodologies and ideologies of children and family life. Social workers sought to wrest adoption away from Children’s Aid Societies, Indian agents, doctors, and lawyers through offering a rigorous scientific approach over sentimental, customary, or dangerous “black-market” adoptions. In the case of Canadian First Nations, Indigenous adoption, where families were involved in choosing the adoptive kin, and bands had the authority to either approve or deny adoptions based on cultural and material considerations, no longer took place once provincial adoption laws became applicable on reserves.26 Unintentionally, Indigenous adoption and child caring practices were colonized in the effort to provide equal services and uniformity.

The 1951 Indian Act Revisions and the Rise of “Jurisdictional Disputes”

The 1951 revisions to the Indian Act, through the inclusion of Indian people under provincial legislation, provided the opportunity for the provincial Department of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation to simultaneously address the perceived Indian and Métis problems. While the Métis did not come under federal jurisdiction, Indian people’s separate legal status added additional complexity to an already highly complex undertaking. The revisions to the Indian Act brought Indian people under provincial child welfare laws for protection, adoption, and juvenile delinquent legislation; however, it was unclear how this would proceed. The CCF, via the Department of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation (DSWR), viewed the Indian and Métis “problem” as stemming from a similar origin: a lack of integration into provincial health, educational, and social standards. Recalling the interprovincial meeting of the ministers of welfare from the western provinces, Minister John Sturdy saw the Métis problem as an overall Indigenous problem. He explained,

Many Métis follow the cultural and economic pattern of the Indians, and that of the Métis problem and that of the Indian is related, together with the effect each group had on the other made it imperative that the living standards and cultural level of these minority groups as a whole should be brought up to a more acceptable level. It is an accepted fact that these groups fall short of the economic and cultural level of the white population and accordingly the groups had a higher incidence of illiteracy, destitution, illegitimacy, and other social problems.27

The conference recommended approaching Métis and Indian rehabilitation together, with assistance from the federal government. “An overall welfare approach to the Dominion would be better if the broad aspects for health and welfare on Dominion-Provincial relations could be arranged, rather than on an individual approach for a Métis problem only. Métis problem alone, or Indian and Métis problem? It appeared that the opinion of the meeting was both.”28 The problems of Métis and Indian people in the province were constructed as primarily social maladjustment to the familial model of the nuclear family, and the inability to integrate into the modernizing economy and society in the west. Consequently, the solution was seen as needing a coordinated welfare response.

Correspondence between the federal and provincial governments on the future direction in provision of welfare services took place shortly after the new Indian Act took effect. Minster of the Department of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation (DSWR) John Sturdy met with Federal Minister Paul Martin (Sr) of Health and Welfare and Minister of Citizenship and Immigration Walter Harris in April 1952, to discuss Indian and Métis issues. Minister Sturdy pointed out that Indigenous cultural and living standards were below those of the rest of the provincial population. Isolation of reserves and jurisdictional disputes prevented the provincial government from providing welfare services for Indian peoples, and he sought federal assistance in a combined approach to the Métis and Indian problems in the province.29 While the province was eager to come to an agreement with the federal government, it quickly found resistance to its approach from federal circles. In areas where social workers could best apply their expertise, such as providing professional adoption services and rehabilitation for unwed mothers, provincial legislation and techniques conflicted with the Indian Act. In addition, the federal government refused to supply the necessary financial commitment to implementing a full-scale welfare response or take on responsibility for the Métis.

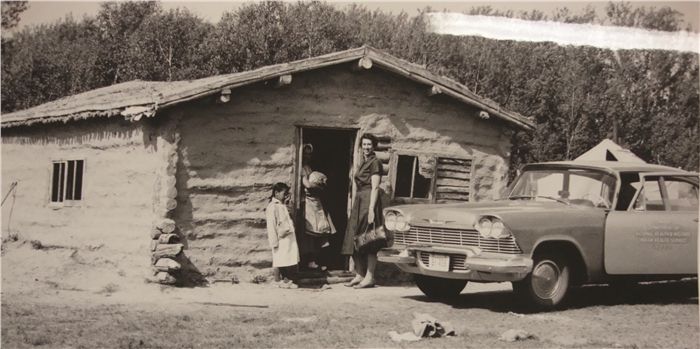

Above and opposite, provincial public health nurses visiting Moosomin Reserve, 1958 (used with permission of the Provincial Archives of Saskatchewan)

Following the meeting, Sturdy wrote to the minister outlining the most pressing issues for the provincial government concerning child welfare, especially in adoption services, protection of children, and services to unmarried mothers. The province’s social welfare policies and procedures clashed with Indian Affairs’ logic of elimination. He explained how the experiences of social workers in Saskatchewan removing non-Indian children from reserves presented “a very difficult situation because these children have been accustomed to the ways of the reserve and the Indians and they do not readily adjust, therefore to other standards.”30 White foster and adoptive homes would not accept the children removed from reserves, and children of Indian unmarried mothers, who had been relinquished for adoption, could not be placed with reserve Indian families as the result of status provisions. Mothers who chose to remain on reserves with children had to be able to prove that the father of the child was a status Indian. Sturdy pointed out, “She is legally Indian, the child is not, and thus not legally entitled to live with the mother. In order for the child to live with the mother on reserves, it had to be determined whether the father was Indian.”31

There was also confusion about whether adopted children obtained the same status as their adoptive parents. The province required clarification regarding section 2 (b), in which a legally adopted child could be registered in an Indian band, which was seen to contradict section 12, which stated that persons of less than one-quarter Indian blood were not entitled to be registered. As a result of the new wording, social workers were hesitant to enter into adoption contracts with Indian parents if the child was illegitimate and the father possibly non-Indian. The author stated, “Our experience has been that the Indian Affairs Branch takes steps to remove the child before the legal adoption may be completed.” The unclear legal status of the illegitimate Indian children then presented problems and questions about whether children could be adopted by Indian relatives. Even if adoption was secured, sometimes it was later discovered that the child did not have Indian status. Sturdy recalled times when recommendations for adoption had been made by a local Indian agent to approve an adoption, after which it was overruled by a higher authority.32 The entire premise of legal adoption as providing a forever family for children and securing legal and cultural kinship was undermined by the patriarchal definition of Indian status.

The province asked for a conference to establish the new direction and begin planning “to give Indians the opportunity to reach adequate living standards.” Sturdy suggested that the governments jointly commence research and planning in economics, health education, and welfare, and also include Métis peoples who were often intermarried with First Nations, with input from a committee of church, federal, provincial, and municipal representatives. The federal government opposed his suggestion. Writing in reply, W.E. Harris, Minister of Citizenship and Immigration, the federal department responsible for the Indian Affairs Branch, abruptly dismissed the concerns of the province for formulating a policy for the extension of provincial services on reserves for Indian people.33 Whereas the province was looking to the federal government for financial assistance for the extension of programs and services to Indian people, the federal government felt that it was “undesirable for the Indian Affairs Branch to duplicate existing provincial services set up to deal with child welfare in areas contiguous to Indian reserves, and we shall be pleased to facilitate the extension of these services to include Indians on reserves in respect to child welfare generally in accordance with provincial law.”34 The lack of financial commitment to extending services or planning for coordination left the extension in a state later described as “unsatisfactory to appalling.”35

While the IAB did not offer to assist with financing Indian welfare services, it did lend its assistance through hiring a social worker for consultation. In an apparent demonstration of modernization and harmonization with the provincial social welfare approach, the Indian Affairs Branch indicated that it had hired a fully qualified social worker with headquarters in Regina, who “will be pleased to co-operate in every way in matters concerning social welfare.”36 However, the single social worker for the entire province was a token gesture at best, and the lack of desire for a clearly outlined plan revealed the federal government’s desire to offload its financial responsibilities to the provinces and disinterest in resolving legal inconsistencies.

Harris went further, disregarding Sturdy’s examples of child removal, and maintained that the new Indian Act made provincial laws apply on reserves, regardless of the different legal regime or impact on women and children. In the matters of child welfare, Harris felt that the new clause in the Indian Act clarified previous ambiguities in federal-provincial responsibilities. Section 88 of the Indian Act – Legal Rights stipulated that all Indians were subject to provincial laws. According to Harris, this section covered the position of Indian children regarding provincial laws governing adoptions, neglect, and delinquency. Generally, in the absence of any provision in these respects under the Indian Act, provincial law applied equally to legally Indian children resident on or off reserves. It followed, therefore, that the adoption of Indian children by Indians or non-Indians, whether resident on or off a reserve, must be in accordance with provincial law. Similarly, provincial laws that governed the protection of children, child neglect, and delinquency applied to all Indian children in Saskatchewan. Harris maintained that rather than muddying the waters, the new act clarified the definition of an Indian and provided for the appointment of a registrar to deal with status and membership problems. If child welfare officials had questions regarding Indian status, the province was counselled to direct all inquiries toward the registrar.

Harris explained the IAB position on legal adoption for Sturdy. Adoption did not bestow a change in status for either Indians or non-Indians, thereby simplifying adoptions for Indian children by non-Indian people and reducing the incidence of adoption of non-Indian children by Indian parents or relatives. The now explicit policy of the government on adoption was that adoption of children did not affect Indian legal status. Section 2(B) of the Indian Act clarified a legally adopted Indian child and therefore did not apply to any children who were not legally Indian. For example, if a non-Indian child were to be adopted by Indian parents, it would not affect status; the child would remain a non-Indian. If an Indian child were adopted, the child would retain Indian status.

In recognizing the difficulty in finding satisfactory adoption placements for Indian children, the Branch provided its version of a sliding scale of preferred adoption and foster homes for Indian children, revealing clearly its goal of fewer First Nations people on reserves. It was the responsibility of the Indian Affairs Branch social worker to compile a list of potential adoptive and foster homes classified according to the needs of Indian children. It read:

1) Enfranchised Indian families resident off reserves who would be prepared to accept children of Indian status.

2) Indian families who have not been enfranchised off reserve and who would be prepared to accept children of Indian status.

3) Suitable Indian families on the various reserves prepared to accept Indian children for either adoption or foster home care. Children placed in such homes on reserves would, of course, have to be of Indian status.

4) Foster homes other than Indian who would be prepared to accept children of Indian status but who by accident of birth have non-Indian physical characteristics.37

Not only did this list reflect the branch’s racial outlook in stark terms, it was also completely unrealistic in expecting off-reserve enfranchised families to provide the majority of homes for Indian children. The enfranchisement rates had been dismally low, with few families choosing to sever their Indian connections. The homes of enfranchised Indian families and off-reserve families were the top placement choices for Indian children, followed by on-reserve families, only after which non-Indian homes were sought. In addition, the branch embraced aspects of the provincial extension of services to Indian people on and off reserve without agreeing to any aspect of financial responsibility. In particular, it refused to contemplate addressing the issues of Indian and Métis people simultaneously since they had no legal obligation to the Métis.

Following the disappointing and unhelpful branch clarification of Indian policy, representatives of the Indian Affairs Branch and the Department of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation (DSWR) met on 23–4 October 1952 in Regina to further discuss the difficulties encountered by department staff surrounding federal policy of absorbing Indians into the mainstream.38 The Indian Affairs Branch representatives included Colonel H.M. Jones, superintendent of Welfare Services; J.P.B. Ostrander, regional supervisor; and the IAB social worker. For the province of Saskatchewan, Miss V.M. Parr, Director Child Welfare; Mr. A.V. Shivon, Director of Rehabilitation; Miss M.E. Battel, Assistant Director of Child Welfare; and Mr. J.S. White, Deputy Minister represented the DSWR. IAB officials informed provincial social welfare representatives that the goal of Indian policy was that Indian people “should contribute to the economy of Canada, and while accepting the obligations of citizenship, should also benefit from Social Welfare programs provided for the rest of the population.”39 This pronouncement of the new relationship with provincial officials would have met a warm reception in Saskatchewan since the CCF government shared the desire to have Indian people integrated through social welfare and education.

The legal and historical barriers to a smooth transition from federal to provincial control of Indian integration were not easily overcome. The central place of adoption in the provincial social welfare strategy for Indian children is indicated by its location as the first item on the agenda for the interdepartmental meeting. Since adoptions were under provincial jurisdiction and no longer undertaken through the federal IAB Indian agents or band councils, as they had been prior to the 1951 revisions, the province needed to determine how to plan for Indian children placed for adoption. Provincial social workers were faced with the illogic that enabled Indian parents to adopt a non-Indian child, but adoption did not enable the child to assume the same status as the parents. Therefore, a non-Indian child legally adopted by Indian parents would not be registered with the band and not permitted to reside with the family on the reserve.40 The central tenet of “modern adoption” was that the adopted child would, in every aspect, assume the same rights and privileges as the naturally born child. Thus, adoption among Indian people became a method of ensuring the gradual elimination of Indian status, and not the reverse. The conclusion was that “no adoption application would be proceeded with or considered until it was cleared by the Branch.”41 While the social welfare principle that “the best interests of the child” applied to the vast majority of children, for Indian children, financial considerations outweighed the social, moral, and ethical considerations. The policy stipulated that “a child who is adjudged a non-Indian should be removed from the reserve because of trespass.”42 In the case of Indian children, policy matters of adoption and child welfare boiled down to the principle “in the best interests of the Indian Affairs Branch.”

At the meeting, federal and provincial officials also established when and for whom the DSWR provided services. In keeping with the newly developing policy of reducing reserve populations and encouraging urbanization, the federal officials proposed an arrangement whereby Indians who had left reserves would become the responsibility of the provincial welfare department after a one-year residence in a municipality. Welfare director for the IAB, Colonel Jones, stated, “This is in line with the Federal government’s policy of making it possible for Indians to leave the reserves and become part of the economic stream of Canada.”43 Through the meeting it was mentioned that municipalities would not necessarily embrace the added financial responsibility for providing health and welfare needs. In addition, it appeared that the IAB was instituting a heavy-handed approach to residents of Indian reserves who had lost status, in all likelihood women and children. Officials said, “A very difficult problem may be encountered due to protests lodged by Indians concerning the status of certain persons presently living on Indian reserves. As a result of these protests some of these persons may be found to be non-Indians and therefore trespassers, for who provision may have to be made for residence and livelihood outside the boundaries of the reserve. These families, unless having made capital improvements, would have nothing to take with them and are likely to become public charges once they are removed from the reserves.”44

While not stated explicitly, these individuals could be women and children who lost status through marriage but had returned to the reserve, Metis families who had married into First Nations communities, and other non-status folks who were related to First Nations families. The kinship bonds that connected these families were fractured through this heavy-handed legislation, and their removal proved especially devastating in these years following. Through the meeting, it was resolved that after one year the province would assume financial responsibility for Indians living off reserve, and the IAB would continue to provide support until that point.

Provincial officials in the DSWR remained troubled by the newly developing policy of the IAB, particularly the impact it would have on the numbers of children who would be separated from their mothers, and unresolved adoption issues. Not surprisingly, Saskatchewan’s social welfare technocrats observed, “There appears to be considerable differences in the philosophy and intent between the provincial and federal legislation, creating as a result many of our residual problems.”45 The Indian problem, as understood by the province, stemmed partially from the boundaries established through legal Indian status, but they believed the cultural differences could be addressed through government rehabilitation policies. “Integration” seemed both the method and the logical solution to the Indian problem. As the DSWR had ascertained with the Métis population within its boundaries, Indian people needed adjustment to the modern economic and social reality. Boundaries formerly erected needed dismantling, since “the cultural, economic, and social pattern of this group was obviously a factor in their present circumstance with little opportunity to integrate themselves as ordinary citizens or the ability to accept responsibilities of citizenship.”46 Recognizing the national scope of their issue, the CCF agreed to approach the federal government with the plan to hold a federal-provincial conference on Indians and their future status as citizens. Rather than adopting a province-by-province approach, as the federal government appeared to want, Saskatchewan sought a national conversation with all the provinces to clarify their future roles in Indian integration.

The origin of “jurisdictional disputes” in child welfare arose from conflicting objectives expressed through law and policy. Following the departmental discussion, DSWR Deputy Minister J.S. White penned a letter to Colonel Jones to express provincial dismay at the “opposite views of our respective offices.”47 The province, in order to establish a partnership with the IAB to integrate Indian people socially and economically into the Saskatchewan economy, felt hampered by the legal barriers erected through IAB, whose only intention was to eliminate Indian status. The newest agents enlisted to bring about Indian assimilation, social welfare experts, brought their professional expertise to the project, soon to discover it was not necessarily welcomed. The sheer insanity of the IAB policy toward unwed Indian mothers, their children, and adoption complications particularly vexed social welfare experts in Saskatchewan. White reiterated his dismay at the Indian status provisions in legislation outlined in earlier correspondence: “The foregoing clearly sets out the legal situation but disregards entirely the social implications of a non-Indian child being adopted by Indian parents and not being allowed to live with them on reserve. Similarly, your position that a child born out of wedlock takes its status from its father is contrary to provincial practice, policy and legislation.”48 In its desire to alleviate the social distance between Indian people and the rest of the provincial population, the province hoped to look at the social factors contributing to the Indian problem, whereas the government of Canada viewed only the legal aspects. Deputy Minister White again requested that a committee be formed to organize the terms of reference for a federal-provincial conference in the hopes of developing a comprehensive analysis of the Indian population in the province and the country as a whole. Deputy Minister White stated, “The idea was to compile information on all people of Indian ancestry in the province in order to formulate a systematic and planned attack on Native problems.”49 CCF’s love of social engineering and planning was resisted by IAB, which refused to consider Métis and non-status issues together with Indian issues. A conference was contemplated again in 1957, when Conservative Prime Minister John Diefenbaker from Saskatchewan took office, but it did not occur. First Nations people in Saskatchewan were left with a confusing and conflicted system.50 Ontario became the only province in Canada to sign an agreement with the IAB to extend all child protective services on reserves in 1965.51

The Indian Affairs Branch hired its first social worker in 1949. Previously, the IAB superintendents in each province had been responsible for the welfare needs of status Indian people. The social work manual laid out the purpose and policy to be followed by Indian Affairs social workers, careful to first inform them that there were some essential differences between Indian Affairs social work and typical case work in a provincial welfare department. To begin with, “the role of the social worker is similar to that of a rural case worker in the Provincial social welfare departments in that she carries a general case load and does not specialize in any case category of social welfare.”52 The branch social workers would offer advice to agents on how to deal with specific problems, reporting and recommending action on certain welfare conditions. Social workers were also encouraged to supervise and establish Homemakers clubs on reserves, stimulate group activities, and develop leadership on the reserves.53 Realistically, “the geographic location of Indian reserves and the scattered Indian population make it financially impractical to staff the Branch with a sufficient number of social workers to allow for this type of concentrated case work, and consequently it is necessary for the social workers to operate as part of a team.”54 Areas where it was suggested that social workers might offer assistance were in aspects of child welfare such as neglect, desertion, adoption, and foster home placement, as well as immorality and illegitimacy.

In the area of child welfare, the IAB informed workers that all provincial child protection legislation was applicable on reserves, and apprehensions might be authorized by courts for neglect. In the event of a child’s apprehension, a transfer of guardianship was needed to make the child a ward of the provincial director of child welfare. In this respect, social workers were encouraged to help provincial agencies locate acceptable Indian foster or adoption homes for children when needed. In the case of foster home placements, the Indian Affairs Branch took financial responsibility for Indian children taken into non-ward care by a child welfare agency but warned social workers that such action should be limited as far as possible to emergency and short-term placements, primarily in urban areas.55 Workers were encouraged to explore the possibility and availability of placements with relatives prior to and for the duration of alternative foster home care. Relatives should be assisted financially with the child’s maintenance only if their circumstances were such that without assistance they would be unable to care for the child.56 The manual stated, “In promoting the foster care programme the social worker should stress the idea of ‘service’ rather than financial remuneration for work done.”57

Regarding adoption, social workers learned that that legal adoption fell under the scope of provincial legislation and included Indians within the adoption programs. Their role was to help provincial social workers by selecting suitable Indian homes. There again, IAB logic differed from child welfare practice, since the selection of appropriate adoptive parents was based on the need to assimilate and integrate Indians. The manual stated, “The success of any child welfare programme is largely dependent on the number and variety of permanent and temporary homes for placement and the need for Indian homes is increasing in proportion to the advancing civilization, the importance of finding homes is an important part of the social workers job.”58 Homes selected using the sliding scale of legal and geographical considerations mentioned above primarily reflected the goals of legal and social elimination, rather than the best interests of the child, family, and community.

The investigation of Indian status of illegitimate children also fell under the purview of social work responsibility. The manual stipulated that prior to band registration, an investigation was required for all illegitimate births, and sworn statements of paternity needed to be obtained from both parents, if possible, in order to be submitted to the registrar for status ruling. Until a definite ruling had been made on the status of the illegitimate child of an Indian woman, the IAB was willing to accept any financial responsibility. However, should the child be ruled non-Indian, it was then determined that the responsible government was required to reimburse IAB to the extent of the financial outlay on behalf of the child.59

After hiring social worker Monica Meade for the Saskatchewan Region, Jones explained the rationale of the IAB. As a social work professional, Meade might have been alarmed at the callous attitude toward women and children in branch policies. He cautioned her that “in the field of child welfare, the Indian Affairs Branch is not always in accordance with the philosophy with which you will be familiar as a result of your expertise in the CAS. Two points: the status of illegitimate children, and adoption and foster home placements. Both of which can be quite frustrating to a social worker unless you have an appreciation for the reason for the stand taken by the IAB.”60 First, the letter contrasted the approach of the provinces on the status of illegitimate children:

Provincial legislation for protection of unmarried mothers and illegitimate children affords the mother all legal rights to her illegitimate child and traces all the child’s legal rights through the mother. The rights of the putative father are limited to financing the support of the child and the mother’s medical costs during pregnancy. An example of the inherited legal rights of the illegitimate child is that of residence, the child’s being traced through the mother, not the putative father. The determination of status in the case of the illegitimate Indian children runs contrary to this accepted child welfare philosophy. In theory no person is entitled to be registered a member of an Indian band with full Indian status unless both natural parents are Indian within the meaning of the Indian Act. In cases where one parent only has Indian status the child is considered “a breed” [crossed out and replaced with “non-Indian”] and not entitled to Indian status. This regulation was created to assure the progressive assimilation of people of only part Indian racial origins in to the non-Indian, or white community and thereby check the regressive trend of the assimilation of such people into the more backward Indian communities. In theory this regulation is sound. It protects the purity of the race (which is the desire of many Indians themselves, particularly in certain areas) it protects the Indian bands financially restricting shareholders in Indian monetary and land rights to the full blooded Indian for whom it was intended and who, in fact are the only legal heirs. And it prevents the development of a race of people who in them would become less Indian than “white” in racial origins, yet would be laying claim to rights and privilege designed for the civilization of a backwards group of people.61

Under the guise of protecting the “purity of the race,” women and children bore the brunt of the IAB’s gendered definitions of Indian status, and provincial welfare departments and their foster and adoptive programs provided a handy, although unwilling, source of support for children being removed.62 White women who married Indian men assumed Indian status, and their children were deemed Indian despite their technically mixed-racial status. The letter continued,

Unfortunately this regulation frequently results in the unnatural situation of an Indian mother having a non-Indian child who is neither entitled to the same rights and privileges as the mother, nor permitted permanent residence on the reserve, but is in trespass and must eventually be prepared to go out on his own and settle elsewhere. Consequently, unwanted children with Indian appearance but non-Indian status present a difficult problem in placement. By reason of their appearance they would be more accepted in an Indian than non-Indian home, but as non-Indians they cannot be placed on reserves. Consequently, they frequently become the problem foster home cases well known to the CAS. The procedure for establishing the status of an illegitimate child is outlined in a department letter that will be on file in your office.63

The letter clearly states that women did not have a right to their children, since children could be removed from their care if found to be non-Indian. Women had the option to leave reserves with children, have them taken from them, or voluntarily relinquish them to social workers. Either way, race and gender converged so that women and children faced a greater likelihood of removal and relocation.

In addition, Miss Meade was informed that in adoption and foster home placements, contrary to professional experience and accepted practice, unmarried Indian women were not generally encouraged to relinquish their illegitimate children for adoption. Jones explained the reason was not that the IAB was unsympathetic to the child welfare philosophy that a child’s future is more secure if raised in a home with two parents, but “simply the facts and figures of supply and demand.”64 Unlike in white communities, where there was an excess of potential adopting parents over and above children for adoption, the contrary was true in Indian communities, where it was felt that the demand for children was low, since “most Indian families have as many or more children as they can cope with, but the potential supply of adoptable children is extremely high owing to the prevalence of illegitimacy.” Consequently, unless Miss Meade felt that the unwanted child would be neglected if left with its mother, or a family was known to exist who wanted such a child for adoption, a mother had to plan to keep her baby.65

Social workers, psychologists, and the state promoted a new role for families in the post–Second World War period. As Mona Gleason has argued, the idealized nuclear family envisioned by experts was no longer bound by outside forces such as the church, law, and economic necessity, but existed primarily to meet the psychological and emotional needs of the members. She quotes from a popular Canadian psychologist, Dr Samuel Laycock, who explained the shifting function of the modern family and the increased demand on parents. He explained this as a “shift in function” from a collaborative productive purpose, “making things,” to the “insistent and urgent” building of personality.66 Experts on family life concluded that in the normal family, not merely in the ideal family, the primary function would be the giving and receiving of love.67 Gendered discourses supported the so-called traditional roles of men and women, with women instructed to be good wives and mothers who remained in the home, and men to be gentle leaders.68 The exacting middle-class standards of psychologists and social workers made it profoundly difficult for groups such as immigrants and Native families living in poverty to live up to such ideals.69 Those who were unable to conform to the race-based, class-based expectation could expect scrutiny of social workers and other helping professionals in assisting with their role. With the rise of psychology, early environmental exposure and experiences determined personality more so than heredity. As Gleason has concluded of the beliefs in the power of the family in the post-war period, “Strong cooperative industrious families meant a strong, cooperative industrious country.”70

The entrenched belief that the solution to the Indian problem lay in removing children from the influence of their parents and reconfiguring kinship relations became reinvigorated with the specialized language of the expert. With introduction of the new Indian Act in 1951, two important developments have had long-lasting effects on the way Indigenous women and children relate to the state. First, the intensification of involuntary enfranchisement policies aimed at Indian women and children eliminated the ability of Indian people to adopt children who had lost status and raise them on a reserve. This development placed women and children in precarious social and economic situations.71 While Indigenous adoption had been utilized for generations to care for children in need of security, the legal apparatus of the Indian Act had ensured that only those legally designated as Indians could be adopted. Second, the introduction of section 88, which enabled provincial laws to be applied to Indian people and on Indian reserves, brought federal patrilineal Indian status provisions into conflict with provincial laws enabling the rights of the illegitimate child to flow from the mother. The continued ambiguity and confusion have led to “jurisdictional issues,” which in turn have led directly to the dismal state of child welfare in Canada. In addition, as social workers took over the role of mediating adoptions, professional methodologies utilizing home studies, ensuring legal marriages and medical certificates, replaced Indigenous criteria. After 1951 integration through transracial adoption and fostering became the vanguard of the new criteria for citizenship.