6

Child Welfare as System and Lived Experience

Consider a part Indian child if you are thinking of enlarging your family. The problems are very small and rewards are very great.1

− Adopt Indian and Métis advertisement, 1967

Termed the “Sixties Scoop,” the removal and subsequent adoption or fostering of Indigenous children in non-Indigenous homes came as a consequence of the increasing child welfare intervention into First Nations Métis families and communities. Métis people in Saskatchewan were targeted for social welfare experimentation in the late 1940s and 1950s under the CCF government of Tommy Douglas in the Green Lake Children’s Shelter, which was later used as a template for Indigenous child removal across Canada. By the 1960s what had been a localized experiment became province-wide. Former president of the Métis Nation–Saskatchewan and former foster child Robert Doucette experienced the child removal policies of the 1960s as a four-month-old infant. He recalled,

When they were taking me away in the car, my mushom [Cree/Métis word for grandfather] was swearing in four languages and throwing rocks at the car. And all through his life he would ask his daughters and his relations to find his little man, he just wanted to see him once. And it was the priest that took me, the priest told social services my mother wasn’t fit, she was too young. She was sixteen or seventeen, and they came and they took me, for no good reason. Because you know all about extended families in Aboriginal communities, it’s not just one person. But that didn’t happen in the sixties. They took all of us, well they took a lot of us. I was four months old when they took me. I was told I arrived in Duck Lake, I just had a diaper, some blanket and a bottle, I was just a big kid, a chubby little kid. Not much else.2

He is one of thousands of Indigenous children who shared the experience of growing up away from their relations, without any knowledge of who they were or where they came from. Robert said,

And that’s not to say that non-Aboriginal homes are not loving homes, or don’t teach really good values to kids. When you see what has happened to a lot of people what has happened because of residential schools and foster home, I think you can come to the conclusion that there has to be a better way of dealing with kids in the foster care system. There has to be.

Like why didn’t they, when my grandfather came asking for me, why didn’t they tell him where I was? What were they afraid of for God’s sake? My cousin was living next door to me on Third Street in East Flat [Prince Albert], the next house!

Why? Why? Why is there such resistance to having those kinship ties? And telling people, “You know what, Robert, you’re a foster kid and here’s where you’re from.” I think, even if you tell the kid it’s not a very good place, they’ll understand. Maybe not the younger kids. I think adults don’t give kids enough credit for capacity to understand…

What’s wrong with telling me that “Robert, you’re the eighth generation of the McKay clan from Buffalo Narrows. Here’s who your relations are.” I’d understand on the maybe woman’s side or the man’s side that they don’t want anyone to know. I understand that. I still think it’s important for families and individuals to know, to have the guaranteed right to know, where you’re from and when you want your file, there’s no bureaucracy no … and no legislations that says you can’t have that.3

Doucette grew up in the northern Prairie city of Prince Albert, formerly known as “The Gateway to the North,” fostered by the Doucettes. They were a respected, working-class French Catholic family who treated their foster children kindly. Nevertheless, Robert and his Métis family’s experiences having him removed as an infant and raised without any connection to his community or kin reflected the aggressive policies of integration that First Nations and Métis people encountered.

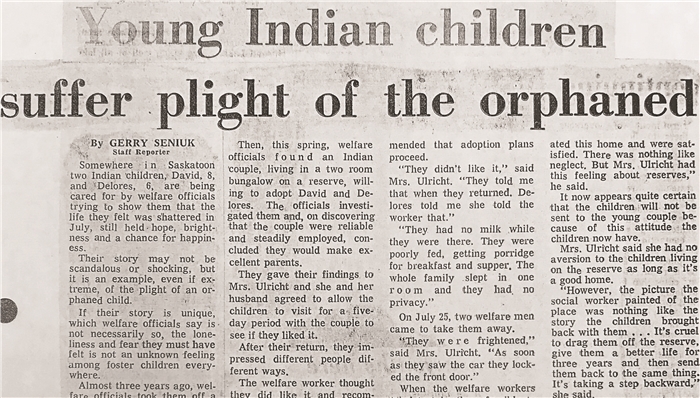

As increasing numbers of Indigenous children – First Nations, Métis, and non-status – entered the care of the Ministry of Social Welfare in the 1960s, policymakers and politicians faced a financial and human resource burden. The “over-representation” of Indigenous children in this period was a reflection of a complex mixture of paternalistic professionalism of social welfare experts, provincial child welfare legislation that unfairly targeted Indigenous families, jurisdictional disputes between federal and provincial governments, gendered discrimination in the Indian Act, poverty and discrimination, residential school impacts, and Indigenous dispossession. In 1969 Indian and Métis people made up a small proportion the overall provincial population (7.5 per cent) in child welfare, while 41.9 per cent of all children in foster homes were Indian or Métis.4 The lack of child welfare services on reserves meant that the provincial workers only apprehended children in cases of the most serious neglect if a child’s life was in danger. However, adoption was available both on and off reserves. Social workers recognized that Indigenous children who were apprehended and remained wards permanently would likely never return home to their original families or communities. Rather than have them facing a life in foster home limbo, social work professionals in Saskatchewan such as Alice Dales, Mildred Battel, then Frank Dornstauder saw the solution in securing white adoptive homes, professionally selected, screened, and most importantly, “normal,” to provide proper socialization for these kids.

The extension of provincial law onto reserves after Indian Act revisions in 1951 proceeded in unevenly and haphazardly, compounded by the conflicting objectives of the various levels of government. Indigenous peoples in Saskatchewan, subject to the contradictory legal regimes and hampered by racial and economic marginalization, continued to find methods to pursue ways of caring for needy children. Whether by activating kinship networks, leaving reserves in search of better opportunities, or relinquishing children for adoption in spite of the resistance of IAB officials, Indigenous women negotiated opportunities despite the very many challenges they faced. The CCF government in Saskatchewan attempted to bring Indian women and children into the orbit of social workers and child protection legislation.

In 1959 child welfare, protection, and unmarried parents services were extended to all Indian families living off reserves, even if they did not meet the residency requirements.5 In 1960 Saskatchewan had 107 Indian children in foster homes. The Indian Affairs Branch (IAB) explained the reason for the increase of over a hundred children since 1957 as “the result of increased services which child welfare agencies now provide Indian families.”6 It would appear that by increased services, the IAB meant apprehensions of children from families. In 1961 a new cost-sharing agreement was reached in Saskatchewan for children taken into care by the provincial Department of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation (DSWR). The branch accepted responsibility for children who were apprehended on reserve, while the province provided the funding for children who had been removed outside the reserve.7 Between 1960 and 1967 Indian and Métis children increasingly left the care of their mothers, becoming permanent wards in a provincial child welfare system ill equipped to provide homes for Indigenous children. The DSWR lamented the lack of willing white families to take Indian and Métis children: “Not only is it essential that homes be found for the Métis and Indian children, but the acceptance and attitude of the general public must change. It is hoped that the adoption of the non-white child will become just another adoption rather than a special placement.”8 In the fifteen years between 1952 and 1967, transracial adoption of Indian children became a logical solution that appeared to resolve the complex web of problems termed “child welfare” stemming from gendered elimination legislation, racialized poverty, jurisdictional issues, and the urbanization of Indigenous people.

The following sampling of cases demonstrates that, despite the policy and legislation governments passed to rehabilitate and integrate Indian and Métis people, some families used adoption to retain family connections, seek relief from child-caring responsibilities, or respond to opportunities for state-based support for caring work.9 Tensions between how Indigenous adoption would develop existed in a tenuous three-way competition between Indian Affairs officials in Ottawa and local IAB officials, provincial social workers, and Indian families. As a consequence, adoption and child welfare have remained contested. IAB attempted to exercise control over family-making by manipulating Indian status legislation, the provincial DSWR through adoption legislation and policy protocols, and Indigenous women and families through Indigenous adoption practices. Modern adoption practised by Saskatchewan’s adoption experts reflected the emerging North American model that promised predictable and safe kinship design, legality, and state-sanctioning, while reinforcing the patriarchal nuclear family model. Describing their approach, Mildred Battel stated, “Each child has to be medically examined and his background investigated and evaluated and personal qualities estimated before a home could be selected for him. Each home in turn had to be as thoroughly studied and evaluated as the child had been in order to ensure that the best possible home was selected for the child. A great deal of time and effort must be given by the social worker to the intricate process of the adjustment of the child and adopting parents.”10

Thus, as provincial law became activated on Indian reserves, social workers enforced adherence to professional adoption protocols in each case, evaluating the merits of private adoptions according to the standard procedures.

An early case of on-reserve Indigenous adoption took place before revisions to the Indian Act took effect in 1946 after an Indian husband returned home from serving in the military to find his wife had given birth to a baby girl. The Indian agent arranged for another family on the reserve to adopt the baby.11 The agent wrote to his superiors, “We have an illegitimate child case which requires adoption in order to settle domestic difficulties between H.W. and her husband who returned from overseas a little while ago.”12 The mother in this case likely did not desire the child relinquished for adoption, but experienced pressure from the Indian agent and her returned husband. This example highlights the role of Indian agents arranging for private adoption on reserves prior to 1951.

Following 1951 Indian women could relinquish children to provincial child welfare agencies if their situation became untenable. One example of a mother who relinquished the care of her two children demonstrates federal and provincial cooperation to make arrangements for the care of Indian children. In a letter from Mildred Battel to Miss Meade, the IAB social worker, on 10 February 1956, they discussed a mother who requested her two treaty Indian children from southeastern Saskatchewan be placed for adoption. The DSWR looked to Miss Meade to obtain the assistance of the IAB to contact the families of the mother and father, as well as find adoptive parents following the policy established by the IAB.13

Another adoption case file from 1954 illustrates women’s pursuit of adoption for their children. After giving birth, one unmarried mother insisted on adopting her baby out against the wishes of the department officials involved. Rejecting the construction that private adoptions were exclusively for middle-class, white women and girls, Mary (not her real name) left her Saskatchewan reserve to go to Winnipeg to have her child and receive adoptive services, much to the displeasure of the Indian agent and other bureaucrats in Saskatchewan. They wrote, “Mary refuses to go to [omitted] Manitoba to her father and also refuses to go to her reserve in SK. She wishes the boy adopted. As it now appears to be an Indian baby we feel it would be best to adopt it legally with a good Indian family on a SK reserve. The better types of families want legal papers…. We have no precedent for adopting a Treaty Indian from one province to another.”14

The bureaucrats discussing the actions of the young First Nations mother seemed particularly concerned that she chose to relinquish her parental rights completely, attempting to find ways to have her maintain ties to her child:

It would not be possible for us to have the baby adopted by Indians on a Saskatchewan Reserve, and moreover we are opposed to the fact of taking illegitimate babies from Indian girls and having them adopted, as we feel that the girls should be made to take responsibility for the matter. If the girl in question knows of a family on her reserve who would be willing to take the child, then we would make any necessary investigations, but we feel that she has responsibility to the child she has brought into the world, and that she be the one to find someone to take care of the child.15

In this case, it was advantageous for the IAB to encourage the maintenance of kinship relations between the child and his relations, rather than support the young woman’s choice of adoption. It served no financial or assimilatory purpose, since the department would be responsible for the maintenance; however, it did serve an ideological purpose. The young girl had transgressed a number of expected behaviours from becoming an unwed mother to exercising her ability to determine where her child would be cared for, without the paternalistic involvement of the department or the Indigenous involvement of kin. She was constructed by department officials as a newly emerging “Indian girl problem”:

The trend lately has been for Indian girls to have babies, then to disclaim all responsibility for them. In many cases they name a non-Indian putative father, a man whose whereabouts are unknown. By doing this they think the Province will take responsibility for the child then the girl herself will be free to follow her previous pattern of life. We, together with the provincial welfare authorities, are trying to do everything possible to fight this trend, for we feel that it is in the interest of the girls in question, to the Indians as a whole, for us to not take responsibility for the care of illegitimate children, except in extreme cases where it is not possible for the girl to get a home for her child, or that the child is suffering in any way from neglect.16

After discovering the child’s father belonged to an Indian band in Saskatchewan, the officials wrote the Children’s Aid Society in Manitoba, asking for a social worker to speak with the girl “in order to see if there is any possibility of having the child placed with relatives, or if the mother is willing to take some responsibility in the matter.”17 Unfortunately for the officials, the mother of the baby signed her consent forms for adoption while she had been in Winnipeg, releasing the child for adoption. On a positive note, the officials acknowledged that the baby was healthy and attractive.18 Despite misgivings, officials managed to locate a young couple on reserve who wanted to permanently adopt the baby in 1954.19

While department officials spent much time and effort to retrieve the baby who had been relinquished in Winnipeg, children of enfranchised Indian mothers were refused such consideration. One case in Saskatchewan illustrates the ambiguous place of orphaned children whose involuntarily enfranchised mother passed away. Despite a resolution passed by the Indian band council accepting the children as members, the superintendent responded to the band council’s decision presented by the Indian agent: “In reply I am returning the signed Resolution to you and as I am fully aware of the stand the department will take in this matter, that is they will be against the admission of these children because their mother married an outsider and the children are not considered as Indian under the interpretation of the Indian Act, I am not submitting this to Ottawa.”20 In spite of the resistance of the federal department, the children’s grandparents approached the Department of Social Welfare on 17 October 1955 to explore the possibility of adopting four of the five children, ranging in age from eight to fifteen. Three had been living with their maternal grandparents on the reserve, and two with relatives also on reserve. The mother of the children died in 1941, at the home of her parents. Following her death, their father had remarried and was no longer involved in raising his children. According to the social worker involved in the case, “The children are receiving good care in the respective homes and the younger ones at least would have no recollection of any other home. It would be desirable to give them security of adoption if it is possible.” The Indian agent, who was interviewed by the worker, stated he would be willing to recommend this adoption. The reply, however, was consistent with the department’s position that stipulated paternal responsibility and patriarchal lines of descent: “For your information I should point out that, generally speaking, I am not much in favour of the adoption by Indians of non-treaty children, as we run into many different kinds of difficulty with regard to education medical cost, etc., and in this particular case, it would appear to me that our department is expected to be saddled with the responsibility of three children while their father is alive and apparently able to re-marry and support a second family.”21

The Indian agent acknowledged the children’s relationship with their community and kin, but department policy was clear that no white people (their terminology) were to be admitted to the band membership. The Indian agent was chastised for his role in advocating the adoption of the children: “You are, surely, aware that it is the policy of this branch to not admit any person of white status to Indian membership and as adoption would not change the status of the children they could not be admitted to membership and should not be permitted to reside on reserve.”22 Fortunately, despite the intended policy to remove the children and relocate them to their father, they remained on the reserve among their kin.

In another case, a potential adoptive father wrote to his Indian agent to ask how he might legally adopt the baby who had been left with his family at two years old. He needed to locate the mother and obtain her permission to have the baby registered as part of the adoptive parent’s band. When the Indian agency wrote to the Department of Social Welfare in Saskatchewan on 23 February 1956, they needed much more information.23 Several steps had to be followed prior to obtaining a legal adoption. The social workers needed to determine if the band would accept the child, they needed to obtain consents signed by the mother, and before the finalization of the adoption, a home study needed to be undertaken: “It is necessary that we have a social history of the child in question, and also that we obtain signed consents to Adoption from the Mother of the child.”24 While the lengthy process required by the DSWR made legal adoption complicated, this example and others have indicated that First Nations peoples actively pursued adoption under provincial statues to establish family for their kin.

During the early 1960s a young unmarried mother sought out adoption, writing a letter to the superintendent of the Southern Saskatchewan Indian Agency. She had been attending school in a small Saskatchewan city and became pregnant. She wrote, “I would really appreciate if you could make arrangements to have my baby adopted out because I don’t feel I could support it or give it the care that it needs. As I was told you’re the one I’m supposed to see about it. I was trying to get somebody to keep her but I could not get anyone. As I want to work, I have a job until winter.”25 The young woman’s lack of kin relations, or inability for kin to assist, prevented her from finding anyone to care for her child. Unfortunately, due to her position as a Treaty Indian, she was not able to obtain services that other mothers might have had. The provincial Department of Social Services, the agency responsible for adoptions in Saskatchewan, did not provide Indigenous unmarried mothers the same support as white mothers.

The Department of Social Welfare explained, “The essence of our discussion with her is that in so far as Treaty Indians on reserves are concerned, we will only become involved with Juveniles and Private Adoptions. The exceptions to this are emergency protection situations. In the latter instances, requests for services must be channelled through your social workers or regional supervisor who in turn will contact Miss Battel.”26 The department was only willing to remove neglected children, or help with private adoptions if there was already someone wanting to adopt. At this point, the DSWR was not providing adoption to Indian children on reserve for lack of willing white families to adopt Indian children.

While these adoptions indicate some mothers relinquished children voluntarily, the vast majority of children came into the care of social services through protection legislation.27 When children were apprehended, most did not end up adopted, but rather entered the foster care system permanently.28 In 1980 Philip Hepworth acknowledged that the available data did not account for why Indigenous children were coming into care.29 It is still difficult to determine with complete accuracy because Saskatchewan’s provincial privacy legislation protects case files from researcher scrutiny. Though it was not acknowledged at the time, communities were reeling from three generations of children removed to attend residential schools, who returned to communities as young adults with unresolved grief and trauma. Only in recent years have the intergenerational effects of residential schools and the historic trauma of Indigenous peoples been recognized as affecting parenting skills.30 Many stories of the impact on individuals, families, and communities from survivor testimonies have come to light through the hearings of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission.31 Several of the cases observed through the federal IAB files indicate families experienced extremely high levels of substance abuse, poor housing, spousal violence, illness, accidental death, suicide, and child abandonment.

Parents, despite their poverty and difficulties in providing a safe environment for their children, attempted to raise children. One case file in the RG10 files graphically illustrates the multiple layers of trauma facing Indian families in the late 1960s. On a northern Saskatchewan reserve, impoverished families experiencing difficulties with substance misuse and interpersonal violence sought the care of child welfare authorities. A mother with three small children died as a result of head injuries sustained by spousal violence. The children’s father also had a severe drinking problem. His second wife also had a severe drinking problem, and their two children had been apprehended shortly after birth due to “failure to thrive.”32 The social worker looking after the case described the family home as a one-room 12’ x 12’ log shack consisting of one bed, a small table, two chairs, one small cupboard, a washstand, a wood heater, and a wood box. At the request of their grandmother, the two younger children from the father’s first marriage were placed in a foster home in Regina shortly after the mother’s death. Once there, the children’s Métis foster mother hoped to be able to adopt the two children. However, the children’s father still wanted to retain contact with his children. He wrote to the department requesting that his children be moved close to him so that he might be able to visit them more regularly: “Dear Sir, I am writing concerning my Children B. and K. I would like to have them back on the reserve or near this area where I can have easy access to visit them when I want to. Regina is such a long way to go and very expensive. I hope to get a house on the reserve where I can look after them. Thank you for your concern.”33 The children were eventually placed with a foster family on their reserve. Grandparents had provided child-caring in Plains First Nations, but family-based care networks were increasingly strained by poverty, addictions, and high mortality rates.34 Grandparents, overwhelmed by caring for children, often sought the assistance of IAB for foster homes.

In some cases, parents who initially requested the assistance of child welfare professionals lost control once their children entered the system. One mother, perhaps unaware that adoption entailed a complete severance of parental ties, sought to regain access to her child once she had become better equipped to care for her child. She wrote, “Dear Sir, I am writing to you about my child [name and birthdate omitted]. I would like to have him back, and I will look after him with my mother’s help. I am writing to you to help me get him back. Thank-you, [name omitted].”35 The Indian agent referred the mother to the provincial Department of Welfare, and it is unknown whether she was ever able to have her children returned. Another mother who had been unable to care for her children as the result of substance abuse, poverty, and homelessness still wrote multiple letters over several years to department officials, attempting to regain custody of her apprehended children. The widowed mother initially sought assistance with caring for her one-year-old child following her husband’s suicide on 1 February 1966. The reason given on her placement sheet was homelessness.36 In March 1966 she began writing to officials, looking to retrieve her daughter:

I sure would like to know what you are going to do with my little B. I sure like to have her back soon I sure miss her. I hope you guys won’t take her away from me. Maybe you are trying to give my little girl away. Hope not. This time I won’t want the welfare take her away. I took that baby in the [omitted] hospital that she was sick and not for my drinking. Why don’t they take [omitted] kid? That kid always goes to the hospital and she left her kids for a week or more. I know all about her instead of me they are lots of people from the reserve that’s …

And I want my B back. That’s my kid. I had the kid for myself and not for anybody. No not for the welfare either. So this I want to know. What are you going to do? I am staying here at F.S.’s place. [Unclear] So please let me know real soon. From Mrs C.M.37

This mother’s incomprehension at the lack of information and refusal to return her children is evident. She gave birth to another baby in August 1968, who was apprehended that November at the hospital, in response to severe neglect. That child was placed in a foster home, where a social worker reported in 1970, “She seemed happy there and was quite attached to Mrs F. There seemed to be a good and close relationship between the child and the foster parents.”38 The foster parents made inquiries to the Bureau of Indian Affairs social worker about adopting the little girl and were told about how to proceed.

This mother continued to pursue the return of her daughters. In 1973, after receiving another letter from the mother looking to have her children returned, social workers investigated the possibility of having the children returned. They reported, after visiting both the mother’s home and the foster home,

13 March 1973: This home is modern, clean and comfortable. V looks healthy contented and well cared for. Mrs F concerned that V not be moved to a different home.

28 March 1973: Saw natural parents. Their home is overcrowded, poorly maintained and in general disorder. Evidences of a drinking problem. One other girl in foster home, evidence of neglect of the rest of their children.

Recommendation: This is an excellent home and no attempt should be made to change the situation at present.

The case file description used by the social worker to contrast the two homes is overdetermined with class and race based value-judgments. The term “neglect” used by the social worker, together with the terms “overcrowded” and “general disorder” signalled this mother’s inability to provide an appropriate home to raise her children and ensured that she could never have her children returned.39 Both children remained in foster homes despite the protests of their mother. Social workers felt the children were well provided for in homes that met their white, middle-class standards. Adoption was pursued by the foster parents of the girls, and since this information is covered by privacy legislation, it is not known whether it was concluded; however since both cases end in 1973, they may have been adopted at this time.

Pregnancies of young Indigenous girls who attended residential schools also emerged in the files. It is not clear beyond this brief note in the Indian Affairs files what the circumstances of the pregnancy may have been. However, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission Final Report has identified that former students from Saskatchewan account for the highest number of claims in the Independent Assessment Claims for cases of physical and sexual abuse, at 24 per cent.40 Certainly Indigenous children were vulnerable to sexual abuse from school staff and other students, and pregnancies resulting from abuse were not unheard of.41 In this case, a young First Nations girl, in grade nine at an unnamed residential school gave birth to a baby while at home for the Christmas holidays. She had given the child up for adoption to another family on the reserve. Her Indian agent wrote, “Irene [not her real name] is 15 years old. I have a return ticket to school on Monday. The principal of the school is not being advised by us of the reasons for her absence. May the adoption be approved at an early date, as the arrangements made seem to be the most satisfactory to us. The [family] are a responsible couple but like all Indians here are on relief. To get the child clothed, I have issued an emergency clothing order and also relief order to foster parents.”42

The placement and adoption was referred to the Department of Social Welfare for its oversight. Because the province had certain legal procedures to follow, the adoption could not be completed immediately. “We will certainly visit the W——’s with regard to their wish to adopt this child, once you have obtained with them their marriage certificate, and once they have completed the attached medical examinations. We realize with the weather so severe they may not be able to complete the medicals soon. However we will be waiting to hear from you when they are completed.”43 The file does not indicate the outcome of this case.

Many factors must be taken into account when looking at the emergence of transracial adoption and the over-representation of Indigenous children. Settler colonial conditions in Saskatchewan rendered families vulnerable, without adequate access to resources for health, education, and healing, while racism acted as an ideological justification for marginalizing Indigenous peoples. Social workers increasingly targeted Indigenous families for child removal, as the case of Robert Doucette illustrates. Likewise, when families suffered from substance misuse related to trauma, poverty from lack of education, employment, and marginalization, without support, difficulties arose in providing for children. In some circumstances, mothers, grandmothers, and even children looked to the foster care system for assistance to cope with the difficult situations in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s on reserves and in cities in Saskatchewan. However, the system was not equipped or inclined to support Indigenous families in caring for children. One informant recalled his difficult childhood growing up with parents who had attended residential school. At age ten he left the reserve with his younger siblings to seek out foster care. His parents regularly left the children without food or warmth in the winter as they suffered from substance misuse. He remembered that he had hoped that the foster home system could provide him and his siblings with the necessities that his parents were unable to. His experience in a foster home did not turn out as he expected. Unprepared for life in in a non-Indigenous community and in a non-Indigenous home, he quickly asked to return home.44 These examples demonstrate the difficulties in making generalizations about Indigenous adoptions.45

Over the course of the 1960s, the extension of provincial adoption laws onto reserves with the application of Section 88 of the Indian Act contributed to a dramatic increase in transracial adoptions of Indian children out of Indian communities. This development necessitated a clarification in registration of adopted Indian children. Since adoption did not change status, Indian children adopted by non-Indians remained on band membership lists. Children’s names were placed under their birth parents’ with an entry that explained that the child had been legally adopted out of the band in a remarks column.46 In each case, a copy of the adoption order or other official document was attached to the membership list, giving the full details of the adoption and the child’s new name. Adoptive parents’ name did not appear on the membership return because information was always treated as confidential. Each child adopted out was entitled to share in all cash distributions made to the other band members.47 The registrar in Ottawa required all the official documents in its attempt to establish procedures that would enable it to meet legal obligations to register persons in accordance with the Indian Act and provide maximum protection of confidential information.48

Keeping track of the increasing numbers of transracial adoptions of Indian children required a process to ensure the IAB retained a record of children no longer on band lists but still eligible for band funds, treaty money, and entitlements. The privacy legislation around adoption made this extremely difficult. Since provincial legislation prohibited the Child Welfare Branch from releasing information on adoptions, IAB officials had to look to Indian parents for copies of adoption orders as confirmation of the adopted child’s eligibility for band registration. Policy directives going out to local superintendents requested that they report all adoptions: “It is requested that you report to Regional office on a confidential basis any information coming to your attention which indicates that a legal adoption involving Indians may have been granted. Regional office may request you … advise Indian parents that copies of their adoption order are needed if their child is to be included on band membership lists.”49 Children leaving bands and communities may not have been recorded on lists if their information was not gathered from parents. Some may not have been informed by foster and adoptive parents that they were entitled to band funds and treaty entitlements when they came of age.

For both federal and provincial agencies, adoption of Indigenous children with or without status provided a solution to the jurisdictional ambiguity between the Saskatchewan provincial and federal governments over responsibility for Indigenous residents, once the legal status of Indigenous adoptees was clarified. Adopted children retained their Indian status, although it was up to the adoptive parents to decide if they wanted to reveal it to their children. Based on the 1951 Indian Act status provisions and Indian affairs long-standing policy, children adopted by Indian people did not receive status through the adoption.50 The Indian Affairs Branch created the position of registrar, who maintained a list of all children, adopted on the confidential “A” band list. The registrar also tracked treaty money and band shares, which were maintained in a special savings account.51 Under the 1951 Indian Act, section 48 (16), legally adopted children were included in the definition of children eligible to inherit property of the intestate. After an amendment in 1956, children adopted through customary adoption could also inherit property of the intestate.52

Adoption as practised by the Department of Social Welfare in Saskatchewan varied, depending on the race and location of the people involved. The case studies reveal a complex interplay between the roles of the Indian Affairs Branch and the provincial Department of Social Welfare. Research of adoption and apprehension files revealed multiple variations of child placement pursued, making generalizations impossible. These cases indicate that the entry of provincial social workers onto Saskatchewan reserves in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s challenged the boundaries of their professional knowledge. Social workers privileged the privatized nuclear-family model situated within the privatized space of the middle-class home. That model reached its high-water mark in the 1960s and 1970s. As Philippe Aries has observed, “The concept of the family, the concept of class, and perhaps elsewhere the concept of race, appear as manifestations of the same intolerance of variety, the same insistence on uniformity.”53 Engineering adoptive kinship to mirror the North American idealized version of the “normal” nuclear family is most evident in the critical importance attached to the home, and the home study prior to the finalization of any professionally arranged adoption.54 The meaning and role of the family had been given enormous responsibility for determining the social behaviours of children – in particular, these nuclear families who were engaged in remaking Indigenous citizens into Canadians.

Social workers preferred permanent, legal adoption to what they considered insecure, temporary placements or other family arrangements that left children without permanent belonging, whereas caring for kin in some Indigenous societies could include a variety of arrangements, some of which could be permanent.55 For North Americans, adoption sought to replicate the nuclear family and provide assurances of permanency, primarily for the adoptive parents. According to Ellen Herman, “It was almost as safe, natural, and real as biological kinship. It might approximate normality through intelligent design.”56 With the increasing numbers of Indigenous children coming into provincial departments, remaking Indian and Métis children into acceptable family members became the new frontier in integration policy.

Adopting a Solution to the Indian Problem

In both Canada and the United States, transracial adoption of Indian children into white homes increased from the post-war period onward. In the United States, transracial adoption of Native American infants into white homes was stimulated in large part through the Indian Adoption Project (IAP) that ran from 1958 to 1967. The special adoption program, operated by the Child Welfare League of America (CWLA), with the financial assistance of the federal Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), sought to provide adoption placements for the Indian children who, according to Project Director Arnold Lyslo, were “‘the forgotten child,’ left unloved and uncared for on the reservation without a home or parents of his own.”57 The IAP began as a demonstration project to encourage white families to adopt Native American children by establishing an interstate adoption exchange between state and county welfare agencies and two eastern adoption agencies, the Louise Wise Services of New York City and the Children’s Bureau of Delaware. The project initially targeted the western states of Arizona, Montana, Nevada, North Dakota, South Dakota, and Wyoming in response to their large American Indian populations. It focused on Indian children of one-quarter or more degree of Indian blood, who were considered to be “adoptable,” emotionally and physically.58 The exchange program, removing Indian children from reservations and regions to faraway families in urban areas, was felt to be necessary recognition that the prejudice against minority children was always strongest closest to their home communities.59

The establishment of the IAP came about during the height of American “termination” policies in Indian Affairs. The cold war era fears of communism sparked a rethinking of the previous reforms undertaken during the 1930s by Commissioner Collier. Termed the Indian “new Deal,” the Bureau of Indian affairs had reversed its decades long policies of assimilation and provided support for Indian self-determination during the 1930s.60 After the Second World War, under Dillon S. Myer, formerly the director of the War Relocation Authority responsible for the removal and internment of Japanese-Americans, the policy of assimilation was restored. Ominously designated “termination,” the newest program renewed efforts to have Indian people leave reserves, phase out the Bureau of Indian Affairs, and have states provide all services to everyone as regular Americans.61 As had been previously done in Canada with the 1951 revisions to the Indian Act, the U.S. Congress passed Public Law (PL) 280 in 1953, giving states jurisdiction over civil and criminal matters on reserves, including family law.62 The BIA also introduced a “relocation” program to stimulate the movement of Indian from reserves into large urban areas. On what was known as the second “trail of tears,” Myers and the BIA relocated Indian people from segregated reserves into urban areas as another facet of the integration program that would see tribal people meld into just another minority in U.S. society. The goal of termination policies was to eliminate the barriers to accessing education and jobs, and eventually see Indian people cease to be a separate legal and cultural entity within American society.63

The Indian Adopt Project drew upon child-removal logic that had made boarding schools the solution to Indian education, despite the poor outcomes for children over the decades.64 The entrenched belief among the white public and policy-makers that the Indian family constituted a threat to the well-being of Indian children enabled white women reformers in the United States who used their privileged race and social position to act as teachers and moral reformers, softening the masculine operation of Indian Affairs. As Margaret Jacobs writes of the early twentieth-century progressives, “White women reformers often claimed that they could transform indigenous homes and thereby solve the so-called Indian or Aboriginal problem simply by teaching removed girls middle-class domestic skills.”65 Through removing children from parents and homes where tribal knowledge, kinship relationships, and collective memories were shared, new subjectivities and sensibilities could be cultivated that would align Indian children with surrounding settler communities. In the shift from the public maternalism of first-wave feminist reformers through federal boarding schools, to individualized private mothering in private homes, transracial adoption sought to inculcate the same social and cultural sensibilities with new methodologies that would enable white middle-class women to continue to provide a solution to the problem of Indian poverty.

Thus the Indian Adoption Project came at a time when American Indian policy shifted intensely towards terminating Indian tribal affiliations through urbanization and integration, and American culture strongly embraced privatized solutions to all manner of complex and troubling problems.66 Extending modern adoption to Indian children, the most intimate form of integration, required selling its possibilities to tribal councils and Indian mothers. Thus, prior to its establishment, Lyslo first canvassed several Indian reservations and four national organizations to gauge Indian attitudes toward adoption of children into non-Indian families and explain to them the need for the project. While some groups, such as the Shoshone, Navajo, Winnebago, and some of the Sioux, had occasionally allowed off-reserve adoption, the Apache and Mojave strongly asserted their desire to have children remain within their own communities.67 Lyslo was confident that once the superiority of such an approach had been demonstrated, with faith and goodwill, “those tribes now opposed to the adoption of Indian children by white families will acquiesce.”68 Although Lyslo had taken the time to consult with Indian leaders, their concerns were not taken seriously, nor was their desire to support tribal adoption considered.

The other prerequisite before transracial adoption could to reach its full potential was to fashion single Indian mothers into the unwed mothers of social case work, and children, as illegitimate children. Social workers needed to re-evaluate their approach to reservation women and children. This meant that Indian mothers would have to accept the casework services of social workers that pathologized Indian marriages and families, and sceptical social workers would have to envision Indian children as in need of adoption. While the BIA had employed social workers on Indian reservations, few had thought Indian mothers and children could benefit from adoption services, since few families considered Indian children as potential family members. Stella Hostbjor, a social worker with the BIA in the Sisseton Indian agency, published her experiences alongside Lyslo’s first account of the IAP in 1961 in Child Welfare. Culturally and socially, Indian unmarried mothers presented a series of issues that added complexity for social workers attempting to offer typical unmarried mothers services as they would for an unwed white mother.

The transition from the old kinship system to a nuclear family has meant less control over family relationships and a great increase in family breakdown. There are many stable marriages which may be legal or so-called “Indian custom.” However, there are also many casual and temporary relationships which do not offer satisfaction or security to the couple involved or the children born to them. The members of this group do differentiate between a legal marriage, a true Indian custom marriage, and a temporary relationship, and are critical of the last. However their disapproval is not consistent enough or strong enough to be much of an influence. Since the state does not recognize the common law marriages all children born as a result of those temporary relationships or Indian custom are considered illegitimate.69

While the unmarried Indian mother was certainly influenced by her culture, and the social position she occupied as a result of her race and poverty, Hostbjor nonetheless felt that “we see her needs as being basically the same as those of other unmarried mothers, but her personality, experiences and cultural patterns, do create differences.”70 One primary difference between the white and the Indian unwed mother was the cultural perception of illegitimacy. Rather than a profound family crisis, as in white middle-class families, Indian families and communities were “very permissive and accepting. 71 There was little evidence of families rejecting children born out of wedlock. Unlike in white families, children were fully accepted, and “we never hear a disparaging tone or term used in speaking of the child, and we seldom hear anyone speak of him with pity because he is a fatherless child.”72 Motherhood without marriage was not seen to be a handicap for either the mother or the child.

The positive gloss placed on profoundly complex cultural and social issues continued unabated in Child Welfare League publications. Agencies responded to the opportunities presented to assist Indian children since, as May J. Davis, the supervisor from the Children’s Bureau of Delaware wrote, “All Americans feel a certain sense of guilt about our treatment of the Indian and so we were glad of the chance to do something concrete to offset out nebulous sense of shame.”73 White families interested in adoption were assured that the children placed with them had been faced with a life of degrading poverty with little hope for future happiness. Davis, after a tour of two reservations, offered her perspective on the advantages of adoption for these children:

Since most children placed for adoption were born out of wedlock, perhaps it is also true that my knowledge is gathered from families with a degree of social pathology. Within these limits I have formed a few rather clear impressions of the Indian on the reservation. I have the sense that for many Indians living on a reservation, there is a dead-end quality and humdrumness to their existence which transcends any ability or wish to accomplish or achieve. The soporific quality of life on a reservation must have some bearing on the fact that, among the families of our children, heavy drinking seems to be the rule rather than the exception.74

The IAP successfully aligned the interests of middle-class families, state social service-providers, and the federal government through professional adoption technologies undermining tribal governments and family ties, and negating the possibility to identify actual economic and social needs of Indian people.

While the CWLA, through the IAP, stressed the importance of high social work standards and application of proper legal adoption channels in transracial adoptions, these standards were not applied in many instances of Indian transracial adoptions. Evidence emerged that Indian mothers and children had become profoundly vulnerable to the heavy-handed tactics of social workers. Similarly to the situation in Canada, the passage of the 1953 law making reservations subject to state civil and criminal law brought a dramatic increase in Indian children into the cases of child welfare agencies. By 1968 one tribe had all its children living in home care.75 Poverty, racial and gendered characterizations of Indian unfitness, and the intergenerational effects of colonial trauma rendered Indian families and children vulnerable to the social welfare interventions to rescue children from the dire futures workers believed awaited Indian children if left on reservations.

By 1967, 395 Native American children in twenty-six states and one territory, by fifty agencies throughout the United States had been adopted through the IAP. The majority of children came from South Dakota (104) and Arizona (112), with the rest fairly evenly split among the other fourteen states.76 By the end of the project, Lyslo proudly stated, “One can no longer say that the Indian child is the ‘forgotten child,’ as was indicated when the Project began in 1958.”77 Stimulation of adoptions brought about by favourable national media representations encouraged 5,000 prospective parents to enquire about adopting an Indian child. Positive “sentiment for our first Americans” in Eastern U.S. communities, according to Lyslo, brought about by the adoption exchange, “caused social agencies in the child’s home states to take a ‘new look’ at the Indian child’s adoptability with the result that many more Indian children are being placed for adoption in their own state.”78 The appeal of the Indian adopted child had reached such a level in South Dakota that the BIA social worker stated, “Here in South Dakota these activities have expanded to such an extent that we really no longer consider the Indian infant a hard-to-place child.”79

By 1967 the success, according to American policy-makers and adoption advocates, of the IAP was clear. It had not only stimulated transracial adoptions of Indian children in faraway regions, it also led to interest in Indian adoption in local states and communities. From 1967 onward, the CWLA developed a transnational exchange. The Adoption Resource Network of America (ARENA) included not only Native American children but also Black, mixed-race, and family groups, and connected children to adoptive families in both Canada the United States. Using the same logic as the IAP, social work professionals believed that greater geographical distance between children and racially intolerant communities would “help overcome the uneven availability of homeless children and suitable adoptive families that now exist throughout the country.”80 Professionals working in transracial and transnational adoptions in the United States and Canada believed that the creation of an international exchange was a necessity for children handicapped by race, family situation, or physical and mental disability. For Indian and Métis children from Canada, it was hoped ARENA would “by-pass the regional prejudices that prevent many homeless children from being adopted.”81

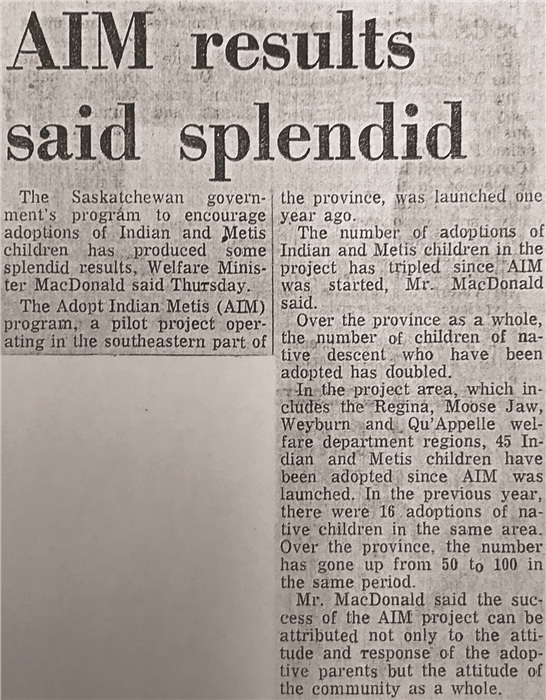

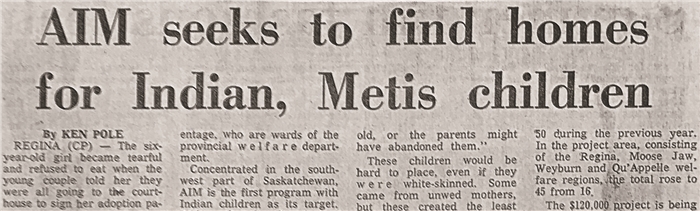

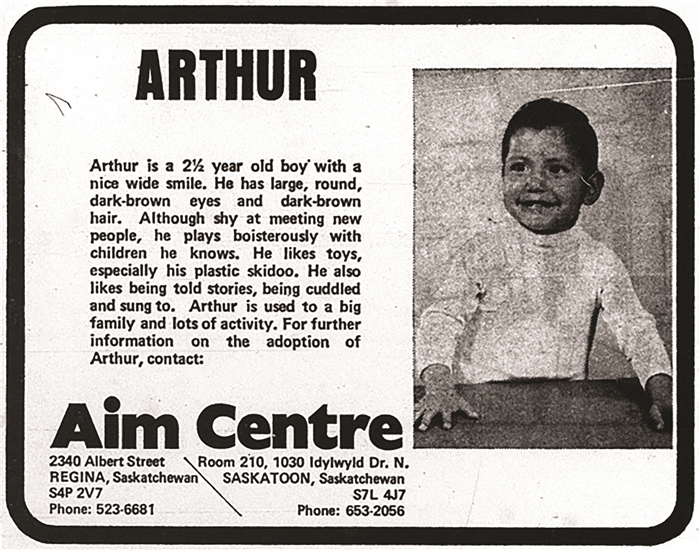

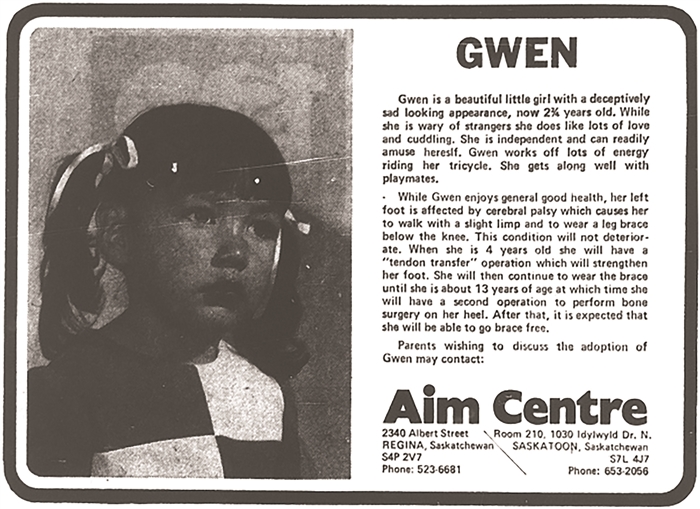

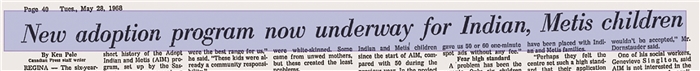

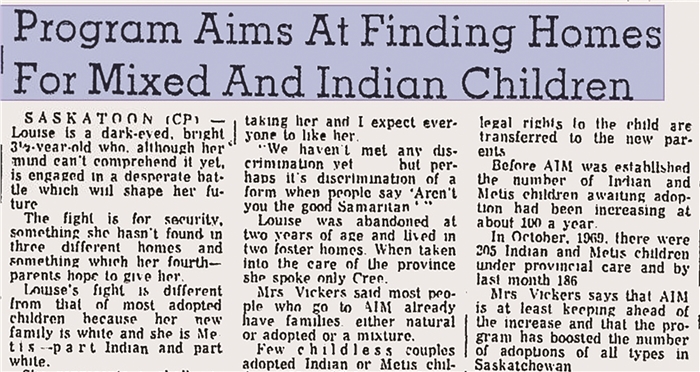

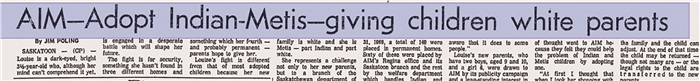

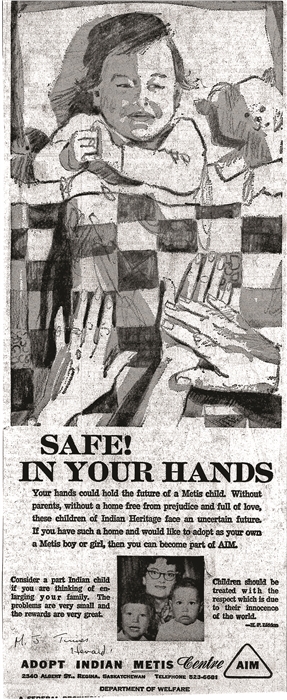

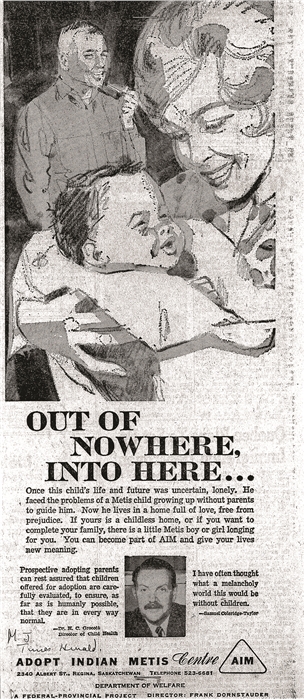

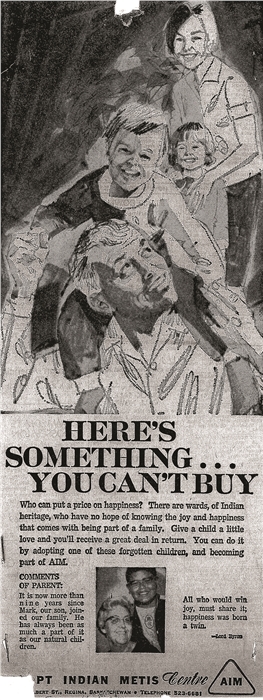

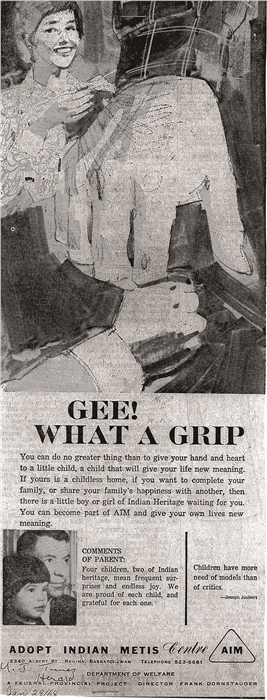

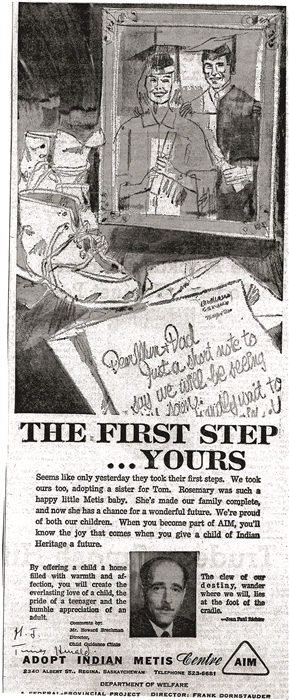

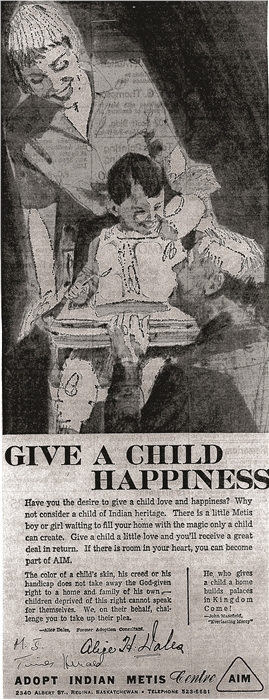

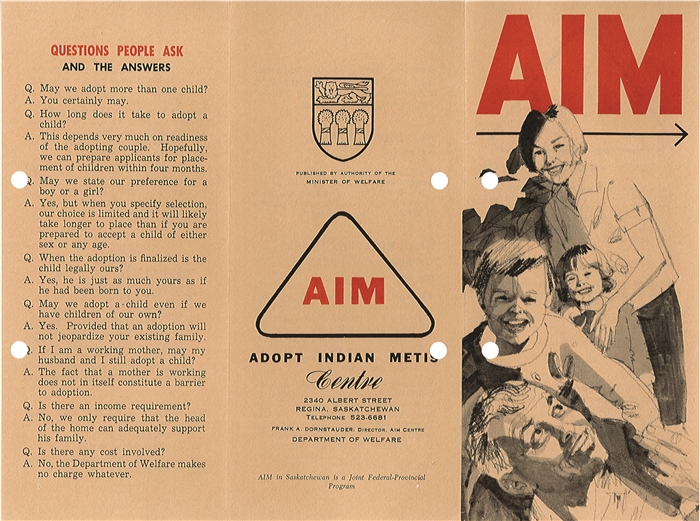

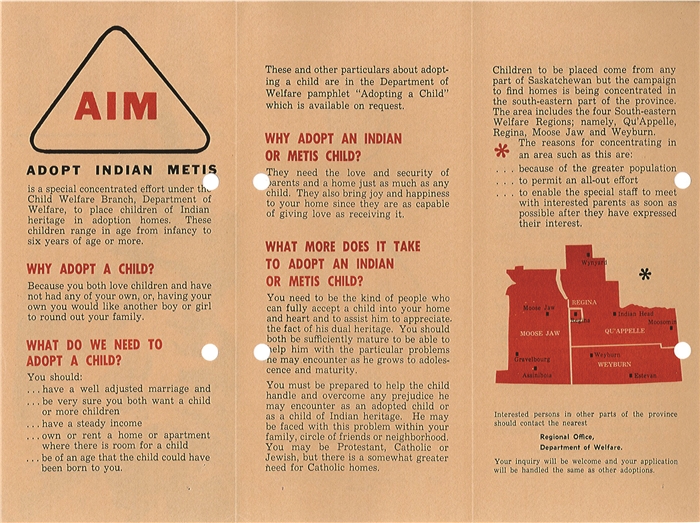

The creation of the Adopt Indian and Métis program in April 1967 in Saskatchewan shared many of the same goals of the Indian Adoption Project. Adopt Indian and Métis sought to secure the permanency of adoption for Indian and Métis children relinquished or removed from reserves and reduce pressure on foster homes by enlisting “normal” Saskatchewan families to adopt Indian and Métis children. The impetus behind the development of a public relations campaign to reconfigure Indigenous children as potential family members was the increasing numbers of Indigenous children being taken into care by the Department of Social Services, for neglect or relinquishment by biological family members.82 Indigenous integration through the provincial child welfare system was failing to live up to its promise, hampered by the unwillingness of the non-Indigenous public to assume its role as potential foster parents or adopters. Selling the idea that the public could provide a solution to the “racial problem” paradoxically relied on denying the relevance of race of Indian children and reassuring non-Indigenous potential parents that the children were in every way the same as non-Indigenous children.

The Adopt Indian and Métis program brought the needs of Indigenous children to the attention of the viewing public in Saskatchewan, erasing their ties to their Indigenous heritage, and offering the public the opportunity to imagine themselves as parents forging a new colour-blind society. The social construction of childhood as a central responsibility of the state and middle-class population first became widespread in the early nineteenth century with the child rescue movement in Britain. The Adopt Indian and Métis program shared a common language and goal with the nineteenth-century child rescue movement in the creation of specific kinds of subjects and bodies to be fundamental in the making of the body politic.83 The “child as future citizen” was the core tenet of child rescue discourse. In the nineteenth century, children were transformed from private parental property to future citizens, and hence the responsibility of the nation.84

Through the use of books, periodicals, melodrama, and children’s literature, the public became aware of its responsibility to assist in rearing poor children and youth. Like the Adopt Indian and Métis ads, often parents were absent from the stories. The primary objective of the publications was first to identify the problem to the public, then attract the financial support of the public for the orphan rescue institutions. As Shurlee Swain points out, “The neglected child, however romanticized, had to be made real if they were going to attract financial support.”85 From its beginnings, child rescue discourse lacked any call for social justice or a roadmap for eliminating the causes of poverty and neglect of children. Like the Adopt Indian and Métis ads, early child rescue literature erased children from their families and histories. According to Swain, “Through the publications, children were constituted as victims, not of an unjust society but of the failing of their parents or other caregivers, often articulated in the old evangelical discourses of morality and sin.”86 The images and discourses of victimized children moved working- and middle-class families to support children’s homes and eventually transracial adoption programs such as Adopt Indian and Métis.

Ross Thatcher and Métis children at Green Lake, 1966 (R-B7227 SAB)

With the election of Liberal leader Ross Thatcher in 1964, the CCF twenty-year rule came to an end. Declaring the province “open for business,” Thatcher gave high priority to resolving “the Indian problem.”87 The expression of this Euro-Canadian intellectual construction has shifted, depending on time and place, but in mid-1960s Saskatchewan the “Indian problem” signified the extreme poverty and growing welfare dependence of Indian and Métis people. In April 1965 the Liberal government created the Indian and Métis Branch in the Department of Natural Resources, the only one of its kind in Canada. The branch was intended to “accelerate the process by which these people become an integral part of Canadian society.” The primary purpose of the department was to find employment for Indian and Métis people.88 In 1967, 89.1 per cent of residents living on reserves in southern Saskatchewan derived their income from welfare, compared with a 4.5 per cent rate for the non-Indian population of the same area.89 Thatcher differed from the previous CCF social democratic government he had replaced; he believed in an individualist strategy, helping individual Indians and Métis take their place in the work world through individual job placements.

In crafting Indian and Métis policies, Thatcher was deliberately indifferent to the legal and cultural differences between Indian and Métis people. Not surprisingly, both Indian and Métis political organizations objected to the direction he took. Thatcher’s emphasis on individual job placements came out of his right-of-centre political philosophy, his opposition to welfare programs, and his desire to see measurable results. According to historian Jim Pitsula, “His vision of the future was that Indians would be economically integrated and culturally assimilated into the dominant society.”90 Thus he shared a common outlook with the federal IAB in bypassing problematic legal and cultural issues and ensuring that individuals assumed their economic and social responsibilities.

From the perspective of the newly elected government, the state of child welfare services for Indian and Métis children appeared troubling and destined to escalate. In a confidential planning document, the Department of Social Welfare outlined the trajectory of child welfare responsibilities if the province continued its course of providing services to Indian and Métis children without the assistance of the federal government or working-class and middle-class Saskatchewan families. While Indian and Métis people made up a small percentage of the overall provincial population (7.5 per cent) in child welfare, 41.9 per cent of all children in 1969 in foster homes were Indian or Métis, and “additionally, an increasing number of Indian unmarried mothers avail themselves of provincial adoption services and leave their children.”91 Lack of child welfare services on reserves meant that the province apprehended children only in cases of the most serious neglect if a child’s life was in danger, and the only other service available was adoption on and off reserves. In most cases, unmarried mothers were told to return to their reserves.92 Planners suggested the need to negotiate for immediate extensions of provincial child care services to reserves or to call for changes to child welfare legislation so that IAB staff could legally take action in neglect cases. The piloting of the Adopt Indian and Métis program in 1967 called for little financial investment and did not require extensive negotiation between federal and provincial counterparts or a radically new approach to resolving underlying economic and social factors contributing to increasing numbers of Indigenous children coming into provincial care. In keeping with the individualist ethos of the Thatcher government, individual children adopted by individual families provided an important method by which to reduce the financial responsibility of the government and provide the nurturing and permanence that was idealized by social work professionals as in the “best interest of the child.”

The first step in creating the Adopt Indian and Métis project was surveying the Indian and Métis children who were permanent wards. In April 1966 adoption consultant Alice Dales, who had been responsible for the Green Lake experiment, conducted a region-by-region survey. She reviewed 373 files to determine which Indian and Métis children were legally free for adoption.93 The stated purpose of the project was to determine if a special approach to the problem of Indian and Métis over-representation would increase adoptions, so fewer children would remain in foster homes. Through the creation of a specialized advertising campaign and immediate follow-up by a unit of workers, Frank Dornstauder, the project architect, hoped the program would encourage white families to adopt Indian children. This plan fundamentally altered the understanding of racial boundaries that the federal government had assiduously erected over the past century in western Canada through its Indian and Métis policies of segregation.

Dornstauder claimed to be inspired by the Montreal Open Door Society, which he was familiarized with while studying for his master’s degree in social work at McGill. The society had been created in 1959 by three families to assist adoption professionals who sought to raise the prominence of interracial adoption of part-Black children through education and support.94 Dornstauder acknowledged that Saskatchewan differed profoundly from Montreal – first, that racial attitudes in Saskatchewan toward Indian and Métis were “more negative than in Montreal,” and second, that the vast rural landscape required an approach that was different from Montreal’s. The project was limited initially to a small geographical area, and after measuring the results, the study would allow administrators to see if the ad campaign could be effective throughout Saskatchewan. Not only would children benefit from the permanency of an adoptive family, there were also pragmatic reasons to explore adoption. As Dornstauder mused, “If it is successful, it will also be a major saving in maintenance costs for children.”95

The federal Ministry of Health and Welfare approved the Adopt Indian and Métis pilot budget for 1967–8, providing funds to run the program for two years. Dornstauder hoped that by demonstrating the universal appeal of children and targeting one specific geographical area with “consistent, continuous, specific publicity,” people would ultimately see the appeal of including Indigenous children as “family.”96 His hope was that “AIM will try to provide the spark and the initiative so that people will investigate the possibility.”97 The southeastern portion of the province targeted by the AIM campaign coincidentally also had the highest concentration of Indian reserves, and although not mentioned by officials, the greatest Indigenous poverty. It consistently ranked last in the Hawthorn Report’s survey of socio-economic conditions across Canada. The per capita income of residents in 1966 was $55 per year, significantly less than the highest paid reserve, Skidegate in British Columbia, at $1252. James Smith Band, one of Saskatchewan’s richest agricultural areas, had an average per capita income of $126. The survey also noted that all households were receiving welfare; at Piapot that number was 86.5 per cent.98

Television was an ideal medium to spread the message through the rural province to a diverse swath of the viewing population. In the televised advertisements for the Adopt Indian and Métis project, playful and innocent First Nations and Métis children appeared detached from their history, communities, and indigeneity. By doing so, the advertising company that created the ads enabled white families to imagine the children as family members and perceive themselves as providing a solution to the poverty and marginalization of Indigenous peoples.99 Ads for the Adopt Indian and Métis project depicted Indigenous children as “normal” everyday children that communicated the colour-blind nature of the project. One thirty-three-second Adopt Indian and Métis commercial showed white parents, and the occasional Indigenous parent, providing care to First Nations and Métis youngsters. Children appeared playing catch, going fishing, practising piano, drinking milk, going to school, being comforted when upset, and being tucked into bed by loving parents. Indigenous children, all between the ages of five and ten, engaged in very typical actions that any Canadian child might. In one scene, a young boy about aged ten appeared to be a fishing companion to a single older man. These children, not infants, represented Indigenous transracial adoption as an opportunity for citizens, moved by the ads, to adopt. The commercial, until then accompanied only by a song, instructed viewers that they could “give a new life to a child in your home. Contact AIM.”100

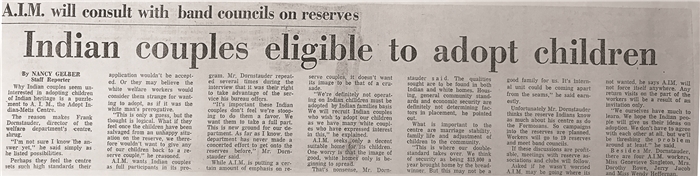

Advertisements ran in the small local community papers as well as in the Regina Leader Post. Newspaper articles provided responses to legal questions that adoptive parents might have about adoption of status Indian children. For example, the article with the title “Homes Sought for 160 Indian and Métis Children: Adopted Children Retain Status” ran 22 July 1967.101 In it Dornstauder outlined how adoptions of Indians would work, explaining, “Until an adopted Indian child reaches the age of 21, laws pertaining to Indians pertain to him. If adopted by non-Indians, he is removed from the natural parents’ band number and registered in a special index for that band. If adopted by Indians, he is registered under their band number.”102 According to Dornstauder, adoptive parents were told by the agency arranging the adoption whether the child was Indian or Métis but were not given the name of the band or band number. It was up to the parents whether they informed their child of his or her Indian status. At that time, the greatest numbers of children available for adoption were Catholic Métis children. The article explained how the children came to be wards of the state – first through illegitimacy, and second through neglect.103

With the completion of the pilot project in late 1969, the department gained new understanding of the power of the media to influence Euro-Canadian Saskatchewan families’ perception of Indigenous children. From the Adopt Indian and Métis project, families took at face value ads’ messages that Indian children were not different from any other child. To quote the government, “Advertising does pay.” It was proven that the definition of the adoptable child went beyond the “blue ribbon baby,” or the white infant in perfect health. Likewise, the streamlined process utilized by Adopt Indian and Métis expanded to all other areas of adoption. In 1970 the Department of Social Welfare introduced the AIM program, broadening the focus to all children who needed plans.104 The AIM program supposedly no longer represented racial designation of Adopt Indian and Métis, and Indian and Métis children became homogenized under the label “hard to place children,” with the promise that adoption “gives the less-than-perfect children the hope of a home and family.”105 The new approach sought to overcome the traditional barriers to adoption that included hereditary risks, health, education, welfare problems, age, sex, race, and membership in a family group. No longer would children be labelled “hard to place,” but rather defined by their greater level of service needs, and the focus shifted from special children to special services.106 Adoption made financial sense, and it was seen as preferable to multiple foster home placements in the lives of children. In the new policy manual, the author rationalized the expansion of the Adopt Indian and Métis program: “One child placed for adoption represents a savings of $1,000 per year minimum. Over a twenty-year period or the duration of wardship it represents a savings of $20,000. If this program placed 10 children for adoption that normally would not be placed, the program would pay for itself. The Adopt Indian Métis program as it is presently constituted places an average of 70 children per year.”107 The Adopt Indian and Métis program provided a complete solution for children and the government, so it would seem.

The imagery of the commercials and messages provided by newspaper articles had a two-fold impact on Saskatchewan residents. On one hand, it stimulated interest in transracial adoption, as planned. During the first year in operation, 16 children were placed through the Adopt Indian and Métis project, and by 1970 the number had risen to 50. However, 137 Indian and Métis adoptions had taken place throughout Saskatchewan outside of the specialized project. Between April 1967, the year AIM’s pilot began, and 19 January 1970, 160 Indigenous children were placed in adoptive homes. With the expansion of the program and office in Saskatoon, adoptive placements of First Nations and Métis children increased. By 1970 there was a balance between children available for adoption and willing homes (see tables 6.4 and 6.5). Officials judged AIM a success in raising awareness of the need for homes by non-Indigenous people, yet recognized that only 5 per cent of homes were Indian or Métis and consistently lamented that they did not recruit more Indigenous peoples. While these numbers represent a large increase, in reality, of those coming into care, only 3.5–4.5 per cent of children were adopted, with the rest remaining in foster care, only rarely returning home.108 Given that the primary reason Indigenous children came into care was poor housing, it was unlikely they would ever return home, for lack of family resources.

Table 6.1. Indian Adoptions in Canada, 1963–75

| Year | Adoptions by Indians | % | Adoptions by non-Indians | % | Number of adoptions | Status Indian population | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1963 | 94 | 168 | 204,677 | ||||

| 1964–5 | 44 | 32.1 | 93 | 67.9 | 137 | ||

| 1965–6 | 43 | 25.9 | 123 | 74.1 | 166 | ||

| 1966–7 | 87 | 48.3 | 93 | 51.7 | 180 | ||

| 1967–8 | 54 | 35.5 | 98 | 64.5 | 152 | ||

| 1968–9 | 57 | 22.9 | 201 | 77.1 | 258 | ||

| 1969–70 | 70 | 31.1 | 155 | 68.9 | 225 | ||

| 1970–1 | 36 | 15.0 | 205 | 85.0 | 241 | 244,113 | |

| 1971–2 | 53 | 15.8 | 282 | 84.2 | 335 | ||

| 1972–3 | 41 | 12.7 | 281 | 87.3 | 322 | ||

| 1973–4 | 75 | 20.0 | 300 | 80.0 | 375 | ||

| 1974–5 | 101 | 27.8 | 262 | 72.2 | 363 |

Source: Figures from annual reports of the Department of Citizenship and Immigration 1963–74; Hepworth, Foster Care and Adoption in Canada.

Table 6.2. 10 Years of Provincial Services to Status Indians in Canada

| Year | No. children in care | No. adoptions | Expenses ($000s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1970 | 5,395 | 241 | 10,042 |

| 1971 | 5,531 | 335 | 10,458 |

| 1972 | 4,467 | 322 | 11,494 |

| 1973 | 4,422 | 375 | 12,351 |

| 1974 | 5,270 | 363 | 14,091 |

| 1975 | 5,390 | 406 | 16,076 |

| 1976 | 5,952 | 581 | 19,806 |

| 1977 | 5,336 | 441 | 20,992 |

| 1978 | 5,659 | 519 | 24,773 |

| 1979–80 | 5,426 | 568 | 25,626 |

Source: Canada, Annual Report of the Department of Indian and Northern Affairs Canada, 1980–1981, “Child Welfare Services, 21,” https://www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/discover/aboriginal-heritage/first-nations/indian-affairs-annual-reports/Pages/item.aspx?IdNumber=38290.

Table 6.3. Statistics on Admission of Children into Care, Saskatchewan, 1973–4

| Apprehension | Relinquished | % apprehensions | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Indian children | 519 | 33 | 94.0 |

| Métis children | 557 | 46 | 92.4 |

| Non-Indigenous children | 712 | 297 | 70.5 |

Table 6.4. AIM Adoption Placements (under 10 years), 1967–70

| Year | Girls adopted | Boys adopted | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1966–7 | 16 | ||

| 1967–8 | 27 | 19 | 46 |

| 1968–9 | 36 | 28 | 64 |

| 1969–70 | 33 | 17 | 50 |

Table 6.5. Provincial Adoption Placements, Saskatchewan

| Year | All adoptions | Indian Métis adoptions | Indigenous adoption as % of total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1966–7 | 501 | 50 | 10.0 |

| 1967–8 | 556 | 96 | 17.2 |

| 1968–9 | 636 | 137 | 21.6 |

Sources: The numbers in tables 6.3, 6.4, and 6.5 are taken from G. Joice, chief, Special Services, to regional directors and adoption supervisors, re: Committee on Adoption Criteria Discussion Paper, 3 June 1974, file I-49, Coll. R-935, Adopt Indian and Métis program, Saskatchewan Department of Social Services, SAB.

Métis children, like Robert Doucette, who were apprehended or relinquished during this period were prevented from having contact with their families and their communities, or having any knowledge of their cultural background. The rich heritage of Métis histories, kinship ties, and land-based identities were either invisible to white experts or deemed insignificant in light of the benefits children would derive from gaining an economically secure nuclear family. Neither Robert nor his grandfather accepted the logic of child welfare or the efforts to erase the kinship connection. Robert reconnected with his family and Métis identity, but the loss of his early years was still a source of pain and disconnection:

My grandfather was one of the founders of Buffalo Narrows, was a justice of the peace for twenty years, had a huge library in the middle of the northern Saskatchewan bush. In the forties and fifties he represented people in court. I didn’t know that growing up. As a matter of fact, doing research, I come across pictures of him every now and then, and I usually shed a tear when I see pictures of him. One day I was in the archives, and I found a picture of him with a caption that that reads, “Happy Métis grandfather with his 13 grandchildren.” Except one. I started bawling, and the archives came there, and asked, “Are you OK?” I said, “Yeah! It’s kind of a sad crying and happy crying, because I finally got to see who my grandfather was. A picture of him.” And there were all my uncles and aunties, just little kids. And you so know when you find pictures like that it’s kind of sad because I never met the guy.109

In the period between 1952 and 1973, the province of Saskatchewan began to integrate Indian and Métis families into emerging child welfare programs. Provincially delivered child welfare services were tasked with socializing families and children to voluntarily accept the roles and responsibilities of citizenship by adjusting personal outlooks and attitudes to embrace Euro-Canadian gender roles, educational aspirations, and employment patterns. It was believed that this outcome could best be achieved through professionally managed transracial adoptions. Realistically, these services never achieved the outcomes promised. Child welfare for Indigenous children operated primarily as child removals in extreme cases of neglect, with increasing numbers of transracial adoptions. Federal and provincial law came into conflict over women’s reproductive choices, with women often losing their children to the provincial welfare department. Gendered and racialized laws intersected, severing familial and tribal ties for involuntarily enfranchised women and children, as social workers became responsible for enforcing the logic of elimination on behalf of the federal government. The extension of provincial child welfare legislation to Indian people meant primarily that Indian parents came under a legal regime that criminalized their many perceived deficits. For both Indian and Métis people in Saskatchewan, the long history of military, economic, and social suppression was ignored, leaving traumatized families to struggle to maintain their integrity and raise their children. For some, adoption and fostering offered the opportunity to stabilize personal situations that included abuse, violence, homelessness, abandonment, and poverty.

The system rarely looked sympathetically upon struggling Indian and Métis families and compared them unfavourably with more stable state-selected families. The Adopt Indian and Métis project shared many characteristics with early nineteenth-century child rescue movements in Britain and North America. The imagery of the vulnerable child in need of rescue through permanent adoption homes appealed to many families in Saskatchewan who had a genuine interest in providing loving homes to children who needed them. The commercials and radio and newspaper ads constructed children as “normal, healthy, and mostly happy children except for the fact they did not have parents and distinguishable from other children only by the fact they were of Indian or part-Indian ancestry.”110 In reality, many of the children did have parents, and their ethnicity as Indian or part Indian mattered a great deal more than the advertising indicated. As was increasingly apparent, the department acknowledged that many Indian and Métis children in care “were found to have a medical, mental, genetic or social problems other than that associated with age or racial origin.”111 The troubling pasts of the children were not erased with a change in birth certificate and removal from their birth homes. Social welfare experts hoped that adoptive parents could “disassociate the handicap from their child’s racial identity and assist the child and community in differentiating between the racial identity and the handicap.”112 The promise of Euro-Canadian methods of child welfare service, and adoption in particular, proved elusive and demanded increasing investment and perhaps a change in focus. The Métis Society and the SNWM rejected the tropes used in the commercials and demanded a say in the creation of policies for Indian and Métis children. Claims made by newspapers and commercials whitewashing the experiences of poverty, racism, and neglect of Indian and Métis people demanded a response.

The programs and policies administered by the Department of Social Services operated under the paternalistic Euro-Canadian belief that the child welfare bureaucracy and family courts alone could interpret the “best interests of the [Indigenous] child.” As Indigenous families struggled to meet the needs of children, and Métis people organized to stem the increasing removal of children from homes and communities, provincial social workers and bureaucrats remained unwilling to divert from the path that was becoming increasingly entrenched.

Early newspaper ads and posters for Adopt Indian and Métis (from Department of Social Services Collection, file I-49, Coll. R-935, Adopt Indian and Métis program, 1967−73, Saskatchewan Department of Social Welfare, SAB)