7

Saskatchewan’s Indigenous Resurgence and the Restoration of Indigenous Kinship and Caring

These ads are racist propaganda against the Métis and Indian people.

− Howard Adams, 19711

In response to Adopt Indian and Métis advertising, the Métis Foster Home Committee led by Howard Adams and Métis activists Phyllis Trochie, Nora Thibodeau, and Vicki Racette researched the creation of a Métis-controlled foster home program. In their letter to the Department of Social Welfare, the committee stated, “In this plan we are proposing a system of foster home care of our Métis children to be placed in Métis foster homes or in group foster homes under the control and management of Métis people.”2 The group had eleven reasons that the government-run system was detrimental to children, parents, and the Métis community. The objections centred on the lack of acceptance by white foster parents who raised the children and the larger white society in which the children were being raised. The final point stated, “We are opposed to a foster home scheme as a relocation or integration program.”3 The society proposed a transfer of the government-run child-caring institution, Kilburn Hall in Saskatoon, to Métis control through a board of Métis parents. They claimed that past experiences with the welfare department had proven that the government was unable to treat Métis people as equal and full citizens. Any new programs or policies without the input and consent of Indigenous peoples would continue to be administered in a repressive and discriminatory way.4 While the discourse of equal treatment and colour blindness permeated the department’s official pronouncements, Métis and Indian people drew upon their own collective experiences of discrimination to formulate their position on child welfare.

During the 1970s Métis and non-status people in Saskatchewan organized to resist the child welfare system. The provincial Métis Society submitted two proposals to provide an Indigenous alternative to caring for Métis children, while organizations formed in Regina and Saskatoon to develop local, community-based responses. In these actions and proposals the Métis identified the complex and historic issues that drove child neglect and removal in Saskatchewan and drew upon historic Métis collectivity support families and children in need. Recognizing the economic and social issues leading to child removal, Métis leadership offered culturally relevant solutions and attempted to mitigate the harms of child apprehension and family breakdown. The foster home proposals were part of the Métis larger self-determination and decolonization movement that recognized the centrality of family to the Métis community.

The Métis Society organized in the early 1930s as the “Halfbreeds of Saskatchewan” to fight for Métis land rights, changing their name to the Saskatchewan Métis Society in 1937 with the creation of a new constitution. The society went through a period of inactivity until the mid-1960s.5 The Métis Association of Saskatchewan, based in Prince Albert, organized in 1964 to represent northern Métis interests, while the Métis Society of Saskatchewan organized in 1965 in Regina to represent southern Métis interests. The two organizations combined in 1967 as the Saskatchewan Métis Society under the leadership of Joe Amyotte.6 In April 1969 Howard Adams replaced Amyotte as president. Influenced by the Black nationalist and decolonization movement while undertaking his PhD at Berkeley in the late 1960s, Adams called on the Métis to decolonize and avoid government funding of any sort, echoing the earlier perspective of northern Métis leader Malcolm Norris.7 The media viewed Adams as a militant and revolutionary, stoking white public fear of violence similar to the U.S. race riots taking place.8

Howard Adams (used with permission from the Gabriel Dumont Institute)

Adams was one of the first Métis intellectuals to write about imperialism, white supremacy, and colonization in Canada. Originally from St Louis, Saskatchewan, Adams sought the decolonization of Indigenous peoples in Saskatchewan after his experience of the civil rights movement while doing his PhD at Berkeley during the 1960s. Adams returned to Saskatchewan in 1966, seeking economic, social, and cultural autonomy for Métis people in Saskatchewan. During his presidency, the Métis Society began publishing New Breed magazine, the voice of the growing Métis nationalist movement in Canada. In 1975 he published Prison of Grass, asserting that Indigenous peoples and people of colour lived in a white racist society, and that racism is the product of economics.9 Indigenous peoples experienced the white supremacy of government, churches, schools, and courts, and in the larger nationalist culture. The “white ideal” was evident everywhere: in the books and movies, and on TV. Through day-to-day experiences of racialization and culturally replicated ideas of inferiority, Indian and Métis were taught to be inferior and seek acceptance in white society. In what Jim Pitsula has called “the rebirth of Métis nationalism,” Adams rejected integration and argued for a separate and decolonized Métis political existence.10

The Métis Society specifically targeted the Adopt Indian and Métis advertising that perpetuated white supremacy and Indigenous degradation. They argued, “These ads are racist propaganda against the Métis and Indian people.”11 The ads implied that Métis parents were unable to look after their children, and they degraded Indigenous children as inferior and unwanted, since “they are displayed as surplus and unwanted children.” To the Métis community, the entire premise of the ad campaign was objectionable because “it portrays our people and nation as being weak because we are portrayed as begging white people to take our children.” Métis people in Saskatchewan felt the ads used their children “to degrade and humiliate our people by playing on our children’s pathetic appearance to have white people care for and support our children.” The society claimed that AIM created the public impression that Métis children were “so unwanted and ugly that the government has to make great efforts to find some kind of home for them.” Further, it suggested that the children were so desperate for homes they would accept any white family who were sympathetic enough. Métis people said the ads were merely the reinvention of a paternalistic racism, reinforcing the negative stereotypes about Indian peoples. Finally, they promoted the idea that Métis parents did not want or love their children.12 They also demanded an end interprovincial and transnational adoption of Métis children into white homes in other provinces or the United States. Seeking control over child welfare was only one component in an overall “revival of Métis nationalism.”13 Métis people began to speak up and challenge the images governments generated for public consumption. Or, as Maria Campbell states of this period, “They started talking back.”14

In response to the letter received from the Métis Society, officials at the Department of Welfare called a meeting with Howard Adams and the Métis Foster Home Committee in Saskatoon. There the government minimized the concerns of the Métis people: “There seemed to be a good deal of confusion in the minds of the Métis people with regard to our Department’s requirements for foster parents. This was clarified very quickly and we indicated that we would be only too pleased to have their assistance in locating Métis foster homes.”15 Officials acknowledged that the strongest point of view presented by Adams was resistance to the images of children used in the Adopt Indian and Métis ads. They considered altering the name, Adopt Indian and Métis, to AIM, to appease the activists and dropping the reference to race, and giving the program a much broader focus. Officials admitted that the resistance engendered by the ads had seriously hampered their ability to work: “The situation is this: our Adopt Indian and Métis Centres in Regina and Saskatoon have been almost immobilized because we have not been able to recruit prospective adopting parents through the media because of the objections raised by the Métis Association.”16 This event marked the beginning of pollination between this group and the Native Women’s Association.

Adopt Indian and Métis publicity ended 1 December 1972 as the result of objections raised by the Métis Society and a commitment to change the focus to include all children. As a result there was a notable drop in inquiries.17 The “change in focus” entailed a name change, from Adopt Indian and Métis to Aim Centre, as well as a silencing on the racial nature of the majority of children the program served. The government responded to “concerns by some native groups … voiced because to these groups the program was seen as a negative reflection on native people.”18 However, internally, officials acknowledged that the majority of children were still of Indigenous origin, but also claimed they had additional “characteristics in addition to being a minority race that were inhibiting placement.” These characteristics included membership in family group, medical problems, physical handicaps, mental handicaps, slow development, age beyond infancy, and other factors that would give a more realistic picture of children’s needs.

While the racial focus of Adopt Indian and Métis was submerged, the centre took on a new role in the facilitation of out-of-province adoptions. Both in receiving inquiries and sending the profiles of difficult-to-adopt children to other agencies, a new international adoption paradigm was taking shape in the early 1970s. The government memo about the change in name also explained the new direction in adoption policy: “With increasing number of referrals coming from other provinces it has become desirable to channel these inquiries and responses through one source and Aim Centre, Regina is currently providing this co-ordinating service as well as referral through ARENA.”19 In 1971 the Adopt Indian and Métis began publishing a bulletin featuring pictures and write-ups on children available for adoption, distributing to provincial adoption authorities across country. Since then, the government began receiving home studies from Ontario, Montreal, Alberta, and Nova Scotia. That year, three infants were placed, one in Quebec, two in Ontario. The new role of the AIM centre was to facilitate transnational adoptions, in the first year placing three family groups of three children in Minnesota, New Jersey, and Colorado. One nine-year-old boy was placed in Colorado, and one four-year-old in Wyoming.20

Despite Indigenous objections, the government decided to increase advertising in 1972–3 and placed a heavy emphasis on its new name and the “change in focus.” On 16 March 1972 a memo sent to all staff indicated, “This is to confirm that effective immediately the Adopt Indian Métis program will be known simply as Aim…. In addition I wish to confirm that the Aim program will no longer pertain solely to Native children.”21 Social workers argued that Indigenous children’s race was merely one factor in a constellation that affected planning and placement possibilities. The Aim Centre merely applied the same principles in adoption service – direct and indirect marketing, specialized and streamlined processes – while denying that the intention was to gain support for the adoption of Native children. The department recognized that Native organizations were increasingly opposed to singling out Indian or Métis children for publicity. However, they rationalized that “while our change in focus will not change the facts of the situation and those facts being that a disproportionate percentage of new permanent wards each year are of Indian and Métis origin, it may be possible to meet some of the concerns of the Native people while at the same time reflecting more accurately the needs of the children.”22 While the Aim Centre claimed to be racially neutral, Indigenous people in Saskatchewan found little to differentiate it from Adopt Indian and Métis: it lacked input from Indigenous people and it continued to rely on the same logic that contributed to the breakdown of families and oppression of Indigenous peoples.

Nora Thibodeau Cummings (used with permission from the Gabriel Dumont Institute)

The Saskatchewan Native Women’s Movement (SNWM) came into existence on 6 December 1971, bringing together Indian and Métis women from across the province to politicize gender and race, and was open to any women of Native ancestry or married to a Native man. The movement advanced the interest of all Native women, whether status, non-status, or Métis. Together, they promoted their common interests through collective action, engaged in research to promote interest in Native women, lobbied government, co-operated with other organizations, and supported the treaty rights of Indian women and the civil and human rights of all Native women in the province.23 Their slogan was “The unity of all women of Native ancestry.”24

Nora Thibodeau (now Cummings) had first-hand experience of the “technologies of helping” provided by Saskatchewan social workers in this era. When interviewed about her life and the time she spent as president of the SNWM, she spoke of her own experiences and those of her sisters and aunts, who were continually under the surveillance of social workers and Catholic nuns. She recalled being a single Métis woman in the city with children and expecting another:

When I had my children, and I had my four children and I was pregnant with my fifth.… They decided that because my first husband and I separated, and they tried to take my children. “We will give you the oldest boy, and we will take the younger boy and the babies.” I said, “You will take nothing.” My exact words: “If you think I’m a bitch dog you got another thing coming. ’Cause you are not taking my babies.” And I remember he had his feet up and I took his feet, and I said, “Send a social worker to my house, I will hammer her. You are not taking my babies.” And they didn’t take my babies. ’Cause I stood up for me. And I know how they did it. It was Sister Obrien’s way of doing things. I had a half-sister who moved away to Edmonton and they tried to take her baby. And these things happened in the city and they happened on the reserve and they happened in our community.

They would walk into homes in the north. And my husband is from Buffalo Narrows. They just walked in and took the baby. And that’s how they’d do things. My aunt, when she was pregnant with her child. It was Bethany home at that time. That’s where mothers would go and that’s where they would take their babies. And there’s lots of untold stories that went on in our city, and I can speak of our city. I was more fortunate because I had my mom, my grandmother, my aunties. I was more fortunate. Other Métis didn’t have that support, and fell into that system, and lost their children.25

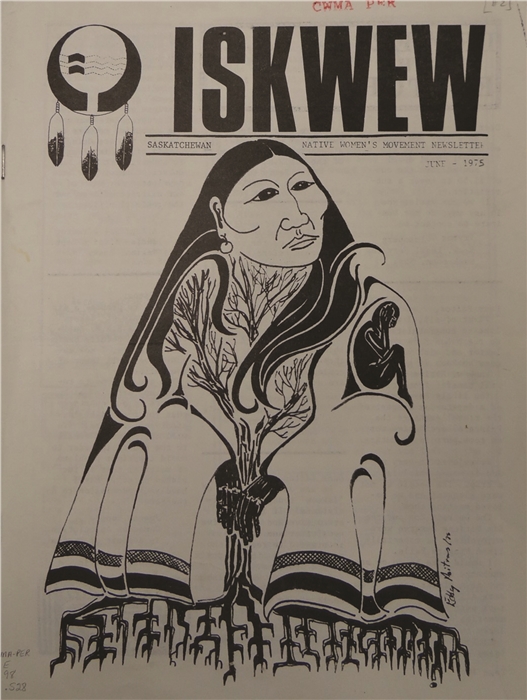

An outspoken advocate for Métis women, Métis families, and communities, Thibodeau played an important role in shaping the SNWM. The provincial organization was in Saskatoon and played a coordinating function, hosting the annual meeting, conducting board meetings, developing special projects, and publishing the monthly newsletter, Iskwew. The first provincial meeting was held in October 1972 in Regina and focused primarily on women’s leadership training. Women from Saskatoon, Buffalo Narrows, La Ronge, Prince Albert, Battleford, Yorkton, Cumberland House, Meadow Lake, Uranium City, and other outlying areas participated. The main function was based on four points: first, to organize at the local level and create unity among all Native people; second, to create social awareness among all Native women to better themselves through community action; third, to help develop programs and to support programs at the community level, such as recreation, day care, old age homes, halfway houses, equal employment, child welfare, foster homes, and education; and finally, to carry out research into Native women’s rights. Unlike other male-run organizations, SNWM organized both treaty and non-treaty women. While they acknowledged that previous organizations had failed, the women hoped to succeed through a better understanding of the historical and political background, along with knowledge of the changes within the Native family unit.

The SNWM looked at areas that male organizations neglected, such as day-care centres in Indigenous communities, on reserves, and in residential neighbourhoods, as well as assistance for mothers who were working, training, or ill. The women sought to establish a halfway home for Indigenous women leaving jail, along with other programs for cultural and economic regeneration of Indian and Métis women. Above all, they hoped to provide needed services from a Native perspective. Their two-year budget amounted to $287,200.26 The organization suffered from unstable funding, since it was viewed by funding agencies as replicating services provided by other Indigenous groups, such as the Métis Society and FSI. It was unable to obtain funding from Indian Affairs because its membership was open to non-status and Métis women.27

Iskwew monthly newsletter (File E.98 S28 ISKWEW - SASK Native Women’s Movement Newsletter - Regina, Sask. Canadian Women’s Movement Archives [CWMA], University of Ottawa)

Indigenous women’s knowledge and experiences informed their decisions on which areas to focus their political and organizing energies. Two themes figured large on the agenda of the SNMW: women’s ability to birth and rear their children and building up the Native family unit. In one meeting, women raised concerns about involuntary sterilizations of Native women in Saskatchewan and suggested speaking to the College of Physicians and Surgeons about the issue. They recognized that they needed to combat what they saw as genocide through forced sterilization and birth control.28 At the same meeting, they discussed their plans to speak out about Aim and work toward its eventual abolition by getting to the root of the social problems that caused Aim to be established. In their analysis of the community child-care needs, the Native women challenged the expectation that grandparents could carry the burden alone of caring for their grandchildren. Extended families had always cared for needy children, but the women realized that people no longer wanted to keep their grandchildren and nieces without financial support because it was increasingly difficult to afford to support additional children. The women believed that working together would enable both men and women to find creative solutions that were culturally and socially relevant to Indian and Métis people.

In an interview with Nora Cummings about the SNWM and the Aim program, she proudly stated, “The Aim ads – we changed it!” She became interested in the Aim after encountering a mother whose children had been advertised by the department for adoption.

I was involved. I was president of Native Women in 1973, and I went to pick up this lady; she was one of my girls I used to work with. I would take her to meetings. That was what we do, we’d work with the women. Her name was Lillian. I went to pick her up; she had this paper and she was crying and she held it. “Look at this: these are my children.” And I look at it and I asked, “What do you mean these are your children? Are you drinking? What do you mean they’re your children?” I turned my car off. And she cried and she told me her story. Her husband died. And she had a breakdown. She had these seven children. So she had a breakdown, and they walked in and took these kids. And they would never give them back to her. And they said they were adopted out; all these year she thought they were adopted out.29

The children were being advertised for adoption and in fact had not been placed for adoption as she had been told. Nora said,

I came back to my little office, I got on the phone and I phoned the women, and we got together with Minister Taylor. Alex Taylor was the Minister of Social Services…. We always made sure that we got involved. We had a meeting at the friendship centre off Second Avenue. We had over 200 people show up at that time the program changed from AIM: Adopt Indian Métis. We didn’t stop there. We did researching more and more, legal aid was just starting then. Judge Barry Singer. So we ended up getting transferred from the Battleford court. It was sad. It was. We got Minister Taylor to work with us. And we found all her children. And she got all her children back. But then she needed a lot of support, so we needed to do that. Last year, at the reconciliation [Truth and Reconciliation Commission meetings] I was one of the elders here at the Prairieland Exhibition, they had a teepee and they had a circle and I was one of the speakers. As I was sitting there someone grabbed me and hugged me and said I was her saviour. And I said, “It can’t be.” And she said, “It is.” And she hugged and hugged and cried and cried. And she told everybody, “This is my saviour: she got my children back.” And we changed that name [Aim] and she’s got grandchildren and great-grandchildren. We are always proud of that. We helped this one lady. And from then things started changing. We were able then to go into the system and build on that. We had women’s groups all across Saskatchewan, women’s centres. People had an opportunity to work with them.30

From late winter to early summer of 1973, the SNWM was engaged in an ongoing campaign to challenge the legitimacy of the Aim program. On 28 February 1973 the Saskatchewan Native Women’s Movement circulated petitions through the New Breed magazine, asking for support to end Aim in Saskatchewan and replace it with a Native Family Foster Home Program. They objected to the ads and the lack of voice in crafting policies for Indigenous children. The SNWM also submitted a brief to the Saskatchewan Human Rights Commission, seeking their support in challenging the policies that excluded Métis and First Nations families from fostering and adopting through the program. Evidence also suggests that the Saskatchewan Native Women’s Movement enlisted the assistance of the American Indian Movement. Department officials at the Aim Centre received a call from an individual claiming to represent the American Indian Movement. The memo stated,

In the telephone call he indicated that he was opposed to sending Native children for adoption out of the country, that the American Indian Movement was going to file an injunction against [ARENA] and they were prepared to file an injunction against Aim as well. No further details were available on these particular points, but the man indicated that he would be back in Regina in about a month’s time if the director of Aim wished to learn more about the matter. He indicated to the worker who took the call that he was serving Aim with notice of their intention. He indicated that they were backing the Saskatchewan Native Women’s Movement.31

The combined frontal assault on the Aim program forced the Department of Social Services to sit up and take notice. The SNWM effectively immobilized the Aim advertising campaign. By today’s standards, the department’s response was tentative and superficial, but realistically it was the first concession to an Indigenous group on input into child welfare policies. In a letter between directors discussing the escalating attacks, Aim Centre Director Gerald Joice stated, “Though the letter [from SNWM] obviously contains misinformation, such fallacies are irrelevant over the long run and we should be addressing ourselves to what seems to be a growing opposition to have the Aim program terminated.”32 He proposed two alternatives for the department: first, they could continue to run the program despite opposition and it would die for political reasons, or they could seize the moment to negotiate through the Saskatchewan Human Rights Commission to change the Aim program in exchange for support of the Native groups developing resources for the children. He suggested the department opt for the second. The Aim director felt that “if it could be possible to work co-operatively with the SNWM groups then a great deal more could be accomplished.”33 He suggested they discuss the SNWM’s objections and make concessions. First, they would be willing to drop the name “Aim.” Second, they were prepared to drop advertising of children aged six years or older, and finally, the department was willing to set up a publicity campaign directed specifically at developing Native homes though not to the exclusion of other homes. In return for these concessions, they asked that the Native Women’s Movement approve the program and support the department’s work whenever possible.34

The new focus on finding Native families acknowledged prior exclusion of Indian and Métis families because of racial and material considerations. Joice made a recommendation:

Basic to a concerted effort to locate homes among Native people is the establishment of a policy with regard to eligibility requirements. For instance it is a fact that Native families by comparison have less to offer materially in terms of educational opportunities, financial security and housing. In order to recruit successfully and develop resources in the Native community, it will be necessary to accept a good number of the Native homes who may be financially dependent on welfare, have only one parent and may be poorly housed compared with homes that might be available within the majority society where there are two parents, much better income and educational opportunities and generally better housing conditions. Unless the department is fully prepared to accept the different standards that will be found in the Native community, there is little or no point in initiating a recruitment campaign for that community.35

The preference for middle-class adoption homes, the goal since the beginning of the Adopt Indian and Métis program, had again hit a snag. While white middle-class families were now more than willing to embrace Indian and Métis children as kin, Indigenous people voiced their rejection of this violation of their own kinship systems. The heavy-handed attempt to exclude Indian and Métis people from participating in the program had been challenged when SNWM and the Métis Society utilized their political and social power to indigenize the policies at the Department of Welfare.

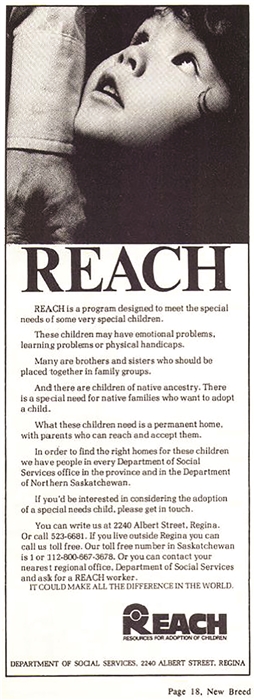

In the fall of 1973 the director of the Aim Centre, now known as Resources for the Adoption of Children (REACH), sent out a memo informing employees of the changes. The new attempt to include Indigenous families as foster and adoptive applicants, rather than as clients, working alongside Indigenous organizations and advertising in Indigenous publications, had never been previously considered. The new objective was to make the adoptive needs of Native wards known amongst parents and potential parents in the community through publicity in Native newspapers. The primarily non-Indigenous employees needed departmental preparation. The circular stated, “The department must be prepared to receive inquiries and process home studies from the Native community on a priority basis. The department must adopt the position that Native wards if at all possible should be placed in suitable homes of Native ancestries. This position requires that the Department give priority to Native inquiries in view of the large number of unplaced and unplanned for Native wards.”36

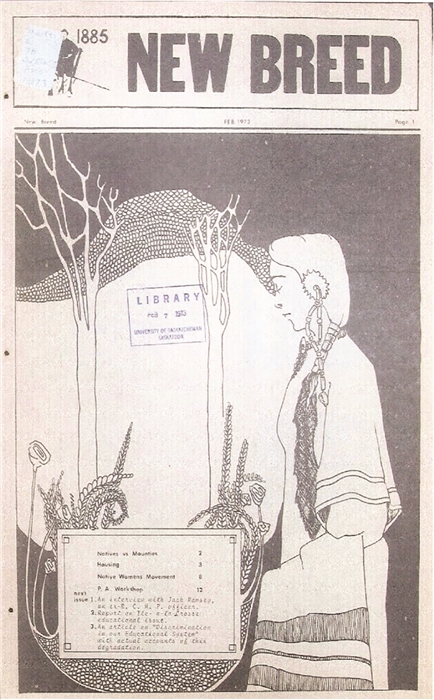

New Breed, February 1973 (The Virtual Museum of Métis History and Culture, http://www.metismuseum.ca/media/document.php/04207.1973%20(02)%20February.pdf)

Not only was the tentative step uncomfortable for the department; for the Métis editor of New Breed magazine, advertising Indigenous children for adoption pushed the boundaries of what Métis people felt were proper family-making techniques. In response, co-editor Linda Finlayson grudgingly agreed to publish ads that had been cleared through the Native Women’s Movement of Saskatchewan:37 “We object very seriously to the advertisement of Native children for adoption through the mass media as the indication is present that our children are being advertised as pets, however as much as our staff object to white families adopting Native children, we have no objection to making your program known to Native people in order that more Native adoption homes can be located and utilized.”38 The tension between the ideology of Indigenous pride and the reality of child welfare needs made running the ads an act of compromise between the government and Métis Society. This tension was apparent in the New Breed magazine where the REACH ads ran alongside an article on genocide, news from Indigenous communities in North America, and the report from the Committee on Indian Rights for Indian Women.39

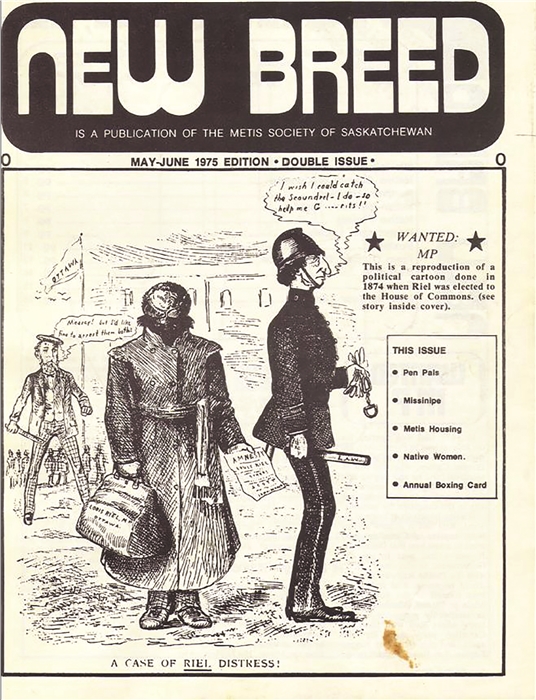

New Breed, May/June 1975 (The Virtual Museum of Métis History and Culture, http://www.metismuseum.ca/media/document.php/05114.1975%20(04)%20May%20June.pdf)

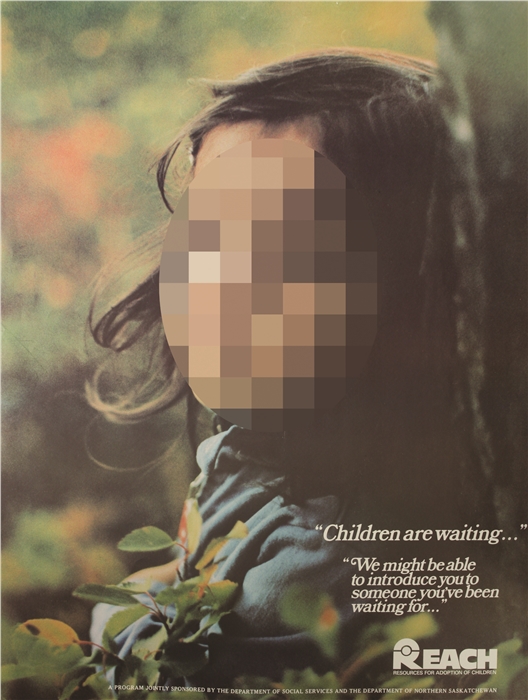

REACH advertisements and posters. Left: advertisement published in New Breed magazine, May/June 1975. Following pages: Provincial Archives of Saskatchewan, Poster Collection, VII.157 (“It doesn’t take much to make a child happy…”) and VII.156 (“Children are Waiting”), REACH programme, Departments of Social Services and Northern Saskatchewan, ca. 1975–76.

Victory for the SNWM in the battle over the representation of Native children in mass media gained the organization a foothold in negotiating with the department. The REACH advertisements portrayed Native families adopting Native children and attempted to represent First Nations and Métis families in a realistic manner that could generate the desired response, that of Native families “reaching” out to adopt a ward of the province. This first step, alongside the creation of day-care centres, women’s centres, publications, and community building was an important aspect of the history of transracial adoption in Saskatchewan. The national alarm over the “disproportionate number of Native children in the child welfare system” was not sounded until the early 1980s. Saskatchewan’s Native women saw this materializing, in their own lives and the lives of their family members since the inception of the Adopt Indian and Métis project in 1967, and organized to challenge it.

In addition to fighting back against oppressive adoption policies, the SNWM developed an extensive plan to open a Native-run foster home in 1973. Arguing that all should have a right to their cultural identity and heritage, they asserted that white middle-class homes “do not afford them the opportunity to grow in the understanding of the beauty of their heritage and the wisdom of their forefathers.”40 Children raised by white parents were caught between two cultures and ended up suffering from emotional and social problems. “In addition to being unable to function successfully in white society, these children are left without the ability to re-establish themselves in their rightful place in Native society.”41 They incorporated Native Homes for Native Children–Saskatoon Society to deal with placement of Native children in foster and adoptive homes. Through the collective efforts of the Natives Homes Society and Department of Social Services, the women envisioned jointly encouraging participation of Indigenous families in foster and adoption programs. The society would not take over control of child caring but would complement the services of the department, assessing needs of Native children, and recommending the most appropriate Native family to social workers. The women also proposed an Indigenous-operated receiving home for Native children, directed and administered by Indigenous people as interim accommodations for children pending placement. In the receiving home, Indigenous staff would assess children and provide counselling for children to assist in adjusting to moving from their family home.

The Native Society consisted of a board of directors, with fifteen people chosen from the community, some with membership in the SNWM and others in related professional fields. Overseen by a director, secretary accountant, staff of ten, and three field workers, the society was envisioned as community-based to provide culturally relevant services. Field workers with community awareness would encourage Native families to participate in the program. In developing the homes, the SNWM identified a need in the community and organized to provide a viable alternative to the government-run system that proved itself unsuitable for Indigenous families. The women recognized the importance of providing Indigenous services for children who were involuntarily caught in unfortunate situations. The first director, Myrna McCulloch, began to search for a suitable home shortly after formation. The society received a $4,000 starter grant, with funding to come from the provincial government. “We have found that the children going that route come out a really mixed-up bunch of individuals.”42

The SNWM also requested a greater role in recruiting Indigenous families as foster parents and a role in the operation of Social Services, calling for the hiring of Indigenous workers: “To date, over a dozen homes have been recruited, seven homes have been approved and three or four are in use. Their tenure for a three month period has been extended a month. The work of these individuals is improving as is their appreciation of the broader problems of placing native children. This is a benefit to the education of both our staff and the native community.”43 With the women’s success, the department proposed further meetings to determine appropriate involvement of Native organizations in its operation.

The collective effort of the SNWM on Indigenous involvement in child welfare led social welfare bureaucrats to seriously consider reforming their policies for the first time. Management agreed that they would have to “come to grips” with the “radical” question of Native staff. On 8 January 1975 in a meeting between Frank Dornstauder, Gerald Jacob, and SNMW representatives Rose Boyer and Vickie Wilson, they were advised that the provincial Métis Society had submitted a separate child-caring proposal, but this was seen to be problematic since they were unable to speak about Indian Children.44 SNWM said they were perfect candidates. REACH Director Gerald Jacob relayed to his boss, “I indicated in this meeting that there must be some budget approved in the coming fiscal year for hiring Native persons for adoption recruitment placements and that I would be discussing their request to become involved in a recruitment program.” Following the meeting with the Department of Social Services, the SNWM held a meeting 24 January 1975 at the Regina Friendship Centre regarding adoption and invited representatives from the Department to be present to answer questions from the grassroots members about adoption and about REACH.45

At the Annual SNWM Conference in 1974, the connections between child removal, self-determination, and the human rights of Indigenous peoples was made explicit. The diverse groups of Indigenous women, First Nations, Métis, and non-status from all across the province with all levels of education made a strong stand for the rights of Indigenous peoples. The women who attended made recommendations for improving the lives of Indigenous peoples in Saskatchewan, in particular, the lives of children. Their recommendation for child-care services for Native children in Saskatchewan called on the province to end the removal of children, a violation of the human rights of Indigenous peoples:

Whereas: the Provincial Department of Social Services Practises cultural genocide by purposely placing Native children in White Homes.

Whereas: Native children suffer cultural shock when placed in an alien white environment and experience further cultural shock when they return to the families in the case of foster care.

Whereas: Aim Centre is contravening no section of the Saskatchewan Bill of Rights and is therefore legally practicing cultural Genocide.

Whereas: The children affected by this bureaucracy have no right to prosecute.

We recommend:

1) That the principle of the right to self-determination be included in the amendments to the Saskatchewan Bill of Rights …

4) That a concerted effort be made by the Provincial Government to recognize and act on a basic principle of Human Rights stated in the United Nations International Covenant on the Economic, Social and Cultural Rights Article 1 Section 1. “All peoples have the right of self-determination by Virtue of that right to freely determine their political status, and freely pursue their economic, social and cultural development.”46

Indigenous women in Saskatchewan argued that the child welfare system violated their human rights and was a form of genocide. Indigenous child welfare did not become a national issue until scholars began to tabulate the numbers of children across Canada in the care of social service agencies.47 Combining the statistics from provincial agencies with those kept by the Indian Affairs Branch, a startling trend began to emerge. From 1973 to 1980, the numbers of Indigenous children coming into care escalated until, in Saskatchewan, Métis and Indian children hovered around 63 per cent of all child welfare cases.48 Indian Affairs kept careful track of the numbers of Indian children adopted, whether into white homes or Indian homes. Transracial adoption of Indigenous children took place in 91 per cent of cases in 1977, but went down to 80 per cent in 1981.49 Social scientist Patrick Johnston termed this process the “Sixties Scoop,” referring to the decade in which Indigenous children became the majority population of the child welfare system in British Columbia. The following chapter will address the way in which First Nations leadership in Saskatchewan responded to this information, drawing on cross-border affiliations and activating transnational Indigenous networks of activists who had worked to curb similar trends in the United States.