Question 2

Does the suspect have especially rapid

growth as it knocks off the competition?

![]()

If a plant spreads more rapidly than other nearby plants, it may well make its neighbors vanish. The methods to achieve such momentum vary from weed to weed, and demonstrate the remarkable versatility and survival skills that can make weeds a mighty and speedy foe.

Weeds show up more quickly on the buffet line created by disturbed soil. With cruder appetites, weeds push ahead of nearby plants to consume the least appetizing nutrients and satisfy themselves with the water and air in harder to access places. Those conditions prevail in compacted soil left behind after construction.

Weeds benefit when their gourmet competitors turn up their metaphorical noses at paltry available soil conditions, especially in pioneer or tough conditions. Weeds, now replenished by sustenance from the meager fare that slower growing cultivars avoided, hurry on to consume the delicacies in the prime, fertile soil. If the cultivars had not begun to dwindle as their prior all-too-limited gourmet diet diminished their population, the cultivars might have survived to enjoy the choicer, richer soils. But the cultivars arrive too late and too ill prepared—perhaps oxygen-deprived, drought-stricken, drowned, or malnourished.

The now well-developed fast-paced weeds use their advantage to race to the prime spaces before the cultivars can. They mark their territory with “keep out” chemicals, shade, soil occupation, or other brutish tactics. Weeds, referred to as “wildly successful plants”, by Lawrence J. Crockett in a book by that title, often succeed better than other plants. Their unfussy predilections and aggressive arsenal help the weeds hustle towards abundant hyper-vitality. Weeds need to speed with greed, since few invite them to the party.

Some weeds seem to grow, even after pulling, the moment you turn your back on them.

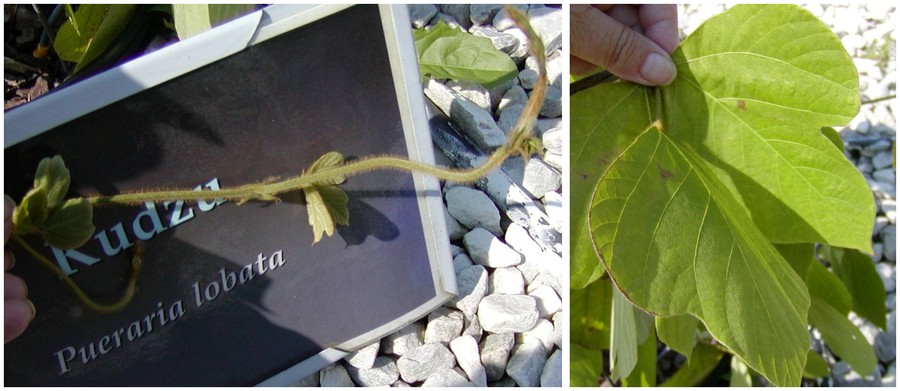

Some claim, hyperbolically, that you can actually watch Kudzu grow. Kudzu, Pueraria lobata, now invades many Southern highways and byways, clambers up telephone poles, and power lines, blankets areas like a carpet, stabilizes hillsides, and excludes most other vegetation.

Some call it “the vine that ate the south” since it can grow 1’ a day to spread 100’ in a season. Massive taproots up to 10’ deep can weigh up to 100 lbs. Trailing vines root at their nodes, and rhizomes form new vines. Its butterfly-shaped blossoms, cross pollinated by bees, ripen into long edible peapods. From fallen or critter-eaten ripe pods, the protected seeds can emerge to germinate and expand its population.

Kudzu was originally imported from Asia for: the beauty of its reddish-purple, fragrant flowers; the fast growth that makes it ideal for adding shade in warm climates like the south; and the tasty, nutritious edibility of its peapods for both farm animals and people. It became useful for soil improvement since, like most Pea family members, it fixes nitrogen into a form that the soil and other plants can absorb, as its root nodules attract beneficial nitrogen-converting bacteria. It forms ample sugars through photosynthesis from its generous sized leaf surfaces, which also shade out competitors. All of these factors fuel rapid growth of nitrogen-fixing roots and enables roots to penetrate even hardpan and made Kudzu a prime choice for soil improvement. In the 1930s local governments and railroad barons planted it to control erosion in impoverished, compacted soil caused by newly built roadways and railways. By the 1940s governments paid farmers to use it to control erosion in poor farmland. Kudzu feasted and flourished on these skimpy rations, then enriched the soil as it grew large and healthy. Then it kept on going. By 1953, governments no longer recommended it as a cover crop. The plants had already achieved critical mass and now continue to burgeon, unaware of governmental decrees.

Kudzu flourishes in hard packed red clay with low calcium and phosphorus. It tolerates airless, poorly-drained wastelands, road salt and chemical debris that daunt most cultivars. Low nitrogen levels signal it to act. Since it requires a warm humid growth period, it has generally avoided the northern cooler states and grown instead in what Scarlet O’Hara lovingly called the red clay of Georgia (which also forms and hardens to an almost impermeable crust in many other places in the south). With global warming and Kudzu’s own inevitable genetic adjustments to its environment, this is beginning to change. Kudzu keeps creeping north.

Left: Kudzu’s hairy vines have vigorous growth nodes Right: Kudzu’s broad leaves create fast shade