Some staggering statistics on weed seeds

• Hedge mustard, Sisymbrium altissimum, over 500,000*,

• Black nightshade, Solanum nigrum, can produce 180,000 seeds*,

• Common purslane, Portulaca oleracea, 195,000*,

• Redroot pigweed, Amaranthus retroflexus, 200,000*,

• Tumble Pigweed, Amaranthus albus, 180,000* seeds in a single season.

*From the book Weeds, by W.D. Muenscher

Fresh new seeds from vigorous weeds arrive all season long ready to germinate, even without soil disruption.

Some weeds have exploding seedheads that speed their spread

Exploding ripe Mustard seedheads produce one of the most impressive quantities of seeds. Another Mustard, Hairy bittercress, Cardamine hirsuta, has skinny seedpods that peel back when touched to reveal the rows of seeds waiting within. Try it yourself. You can watch them pop as if animated. No need to wonder how Bittercress or other “mustard seeds” take over garden beds with such alacrity. This accounts for the mythical repute of the power of the mustard seed. Religionists contend that if we but have the faith of a tiny mustard seed, our faith will grow and spread with vigor.

Above: Exploding seedpods of Hairy bittercress

Left: Bittercress flowers cluster as seedpods (skinny tubes) emerge and as a pollinator visits Right: Bittercress in a rapidly reproducing colony

It’s not just the Mustards that can explode to expel seeds. Redstem filaree, Erodium cicutarium hides in plain sight as it mimics its botanical family members, the hardy Geraniums, Geraniaceae. Its ability to blend in with cultivars and the explosion of its seeds are just a few of the reasons this beauty multiplies so rapidly.

Some weed seedcases have tails to help them penetrate the soil.

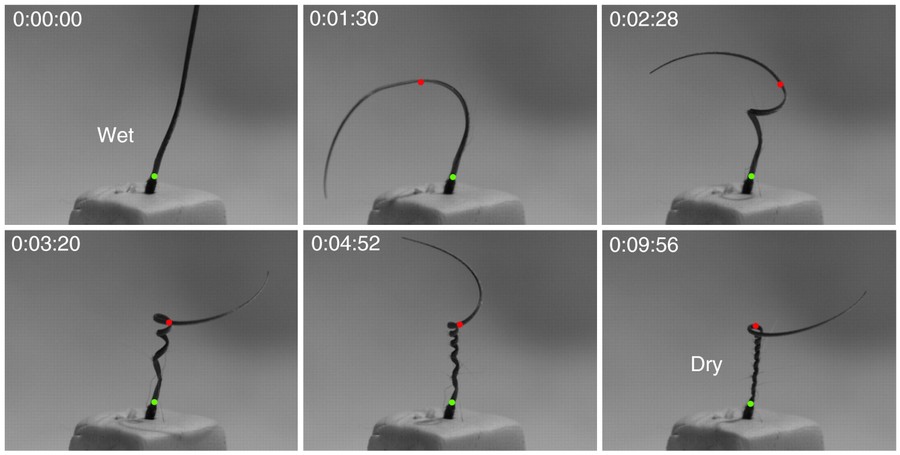

Remarkably, when the seeds of Redstem filaree, Erodium cicutarium alight, tails on seedcases spiral when dry, unwind when damp, and so on until it corkscrews itself into the soil, the way Wild oats, Avena fatua, do. This behavior of Wild oat seeds gave rise to the expression “sowing his wild oats”. The Journal of Experimental Biology’s power point presentation (below) demonstrates beautifully the way Redstem filaree penetrates the soil. It sure screws up the crops as its seeds screw into the ground and take hold. It takes as little as 3 weeks for Redstem filaree to reduce crop yields of Wheat, Canola, Dry beans, Potatoes, and Peas by 20% to as much as 92%! During droughts, which it tolerates, it overruns crops that can’t tolerate drought. It develops too fast to give control methods a large enough window of time for effective application. Filaree also hides in plain sight as it looks like cultivated hardy Geraniums and certain wildflowers, but with proportionally smaller flowers.

Left: Redstem filaree seedpods prior to eruption Right: Wild spread of Redstem filaree after eruption

Above: The mechanics of explosive dispersal and self-burial in the seeds of the Filaree, Erodium cicutarium (Geraniaceae) from the journal’s website at http://jeb.biologists.org; Journal of Experimental Biology February 2011 vol. 214 no. 4 521-529

Other weeds re-seed repeatedly in rapid cycles

Common groundsel, Senecio vulgaris forms “Puffballs”, fluffy seedheads, concurrently with flowers. Its seedheads can emerge from flowers in just 24 hours. It normally develops 3-4 generations in one season, at a swift rate of maturity, often just 5 weeks from germination to seed formation. But it speeds that up to adjust to competitive pressures in well-weeded sites where it forms even quicker-growing generations of dwarf offspring that precociously develop to seed even earlier. If grazed, Common groundsel overcompensates and promptly forms new foliage and seeds. In temperate climates like California it can bloom year round and produce even more generations, yet it can flower even when temperatures drop below freezing. Each plant can produce up to a million plus offspring in a season. Seeds become sticky when wet which helps them hitchhike on passersby. Seedcases topped with hooked parachutes float. Hard seedcases survive in water and benefit from animal digestion. It outcrosses to produce prodigious populations of ever-evolving and changing seeds over a long season. Its remarkable genetic plasticity enables it to adapt to resist most herbicides. It also self-pollinates to keep up the pace. Its common name comes from the Anglo-Saxon “groundeswelge” meaning “ground-swallower”, and the name proclaims its fame.

Left: Common groundsel seeds & flowers simultaneously Right: spreads quickly in a neglected spot

Perennial sowthistle, Sonchus arvensis, matures so fast that within a single spring and summer multiple generations can re-generate to overwhelm the succession of awakening perennials.

Left: Perennial sowthistle has tiny quickly formed flowers… Right: and large quickly formed seedheads

It produces and spreads up to 13,000 lightweight seeds per plant by its second year. After pollinators fertilize any of its up to 60 nectar-filled flowerheads, each of which has 150-240 florets, florets form hard, lightweight seedcases that remain viable for up to 6 years. Seedcases of Perennial sowthistle are topped by parachutes with hooked cells on their tips to help them fly, hitch rides, and spread.

The fluffy seedheads of some weeds disperse their seeds in light breezes

Like the fluffy puffballs on Perennial Sowthistles, Sonchus arvensis, Dandelions, Taraxacum officinale, or Common groundsel, Senecio vulgaris, some seedcases have special parachute-like structures tipped with hooked cells to help carry them aloft and then to stick where they land. Puffballs delighted us as children, as we made a wish and blew upon them. Several commercials on TV feature this act as a symbol of romance and free-spirited fun, since so many of us enjoyed this pastime. Even some “screen saver” programs feature the ripe seedhead of a Dandelion as a thing of beauty that tempts the viewer to puff on it. Little did we imagine the distress it might cause our neighbors, as we released future generations of Dandelions everywhere.

Left: Dandelion seedhead with hard cases plus parachutes atop receptacle which resembles a dimpled golf ball Right: Fireweed also has fluffy puffball seedheads and golf ball like empty receptacles atop spent bracts

Several other Composite, Asteraceae, family weedy flowers, have this same fluffy puffball seedhead, such as 6-7 foot tall Fireweed, Erechites hieracifolia, (above) and Meadow salsify, Tragopogon pratensis (below). The flowers on Fireweed resemble a larger version of the flowers on Groundsel, while the flowers on Salsify resemble a profusion of Dandelion flowerheads. Every parachute with its attached seed represents the output of each of the multiplicity of florets within each flowerhead. Microscopic study of the parachutes (“pappus”) reveals barbs or hooks at the tips of these parachutes which also helps these seeds hitch rides on pasersby. Remarkably, microscopes also reveal multiple tubes that comprise each pappus. These retain water and thereby provide seeds with their own water supply to help them germinate wherever they land.

Left: Salsify seedhead Right: Field of Salsify with puffball seedheads and empty receptacles

The special coating on many weed seedcases makes them durable and helps with rapid spread.

In Composite family flowers, like Sowthistles, Dandelions, Fireweed, and Salsify hard outer seedcases, called “achenes”, attach to the receptacle in the center of the flowerhead to be released when ready. Short brownish achenes below the longer parachute tops of the Dandelion are clearly visible above. This hard outer coat protects the seeds within. The achene helps the whole unit to survive until conditions are just right for the seeds to emerge after a restful slumber in the soil seed-bank.

Hooks

Seedcases of some weeds hitch rides on the fur of migrating animals or in shoe and tire treads. Adaptations on seedcases do not include an outstretched thumb or lanky leg (like Claudette Colbert’s), but rather more subtle, effective structures. Devil’s beggarticks, Bidens frondosa, another Composite family member, has seedcases with hooks and, to me, these seedcases resemble devil’s heads with horns.

“It is as if you had unconsciously made your way through the ranks of some countless but invisible Lilliputian army which in their anger had discharged all their arrows and darts at you, though none of them reached higher than your legs.”—Thoreau describing Bidens frondosa in October in his Journal

Left: Devil’s beggarticks seeds stuck to sweatpants Right: Devil’s beggarticks flowers developing into seedheads

Sticking seedcases help other weeds to spread quickly.

Burs of Common burdock, Arctium minus, that had ridden home in the fur of his dog, inspired the Swiss engineer George de Mestral to study them under the microscope. The curved, spiny, tiny, multiplicity of hooks on Burdock burs and their tenacity in staying stuck inspired him to invent Velcro. Some still call it the Velcro plant.