1

According to the Customer’s Desire

The First Delicatessens in Eastern Europe and the United States

An illustrated advertising postcard from a Belgian butcher and food shop from the mid-nineteenth century is decorated with colorfully plumed birds, clusters of grapes, and an iron cooking pot on the bottom. A petite oval at the top, as if a window into an upper-class home, shows a nattily dressed gentleman sitting at a table with knife and fork in hand, preparing to dig into a feast of fancy foodstuffs. The caption, in French, lists all the meats, cheeses, pâtés, and other items that are available for purchase from the shop, which promises that everything will be prepared “according to the customer’s desire.”1

Perhaps it should not surprise that the pastrami sandwich became an object of such potent and piquant obsession in Jewish culture, given that the very word delicatessen derives originally from the Latin word delicatus, meaning “dainty, tender, charming, enticing, alluring, and voluptuous.” Indeed, the Romans often used the word to refer to sexual attractiveness, as in the expression puer delicatus, the “delicious” boy, who was the recipient of an older man’s erotic attentions. It entered medieval French as delicat, meaning “fine,” and by the Renaissance morphed into delicatesse, signifying a fine food or delicacy. It was picked up as delicatezza in Italian and Delikatesse in German, both also denoting an unusual and highly prized food. It entered English only in the late 1880s, with the influx of Germans into the United States, and then only in the plural form, delicatessen.

Advertising card for a Belgian gourmet store from the mid-nineteenth century (Collection of Ted Merwin)

The origin of the delicatessen as a food store derives from the democratization of gourmet eating in Europe. This occurred at some times through political upheavals such as the French Revolution, after which many chefs found themselves out of work, and at other times as a result of papal decrees. Pope Gregory XIII, who was invested in 1572, inveighed against the bishops and cardinals of his day for eating sybaritically despite their purported devotion to austerity and self-abnegation, and he mandated that they could employ no more than one chef apiece.2 Unemployed chefs opened Italian specialty food shops called salumerie in which cured and smoked meats were sold to members of the haute bourgeoisie who, unable to afford their own chef, still desired to eat like a king—or a pope. Among the specialties of these stores were cured meats, which were especially popular in Italy. According to the Harleian Miscellany of 1590 (first collated and edited in the mid-eighteenth century by Samuel Johnson), “the first mess [course] or antepast, as they call it, that is brought to the table, is some fine meat to urge them to have an appetite.”3

Delicatessens competed to provide the most unusual foodstuffs from around the globe. Their ostentatious, symmetrical window displays, which typically featured the head of a wild boar (the origin of the name for Boar’s Head, an American company that was founded in 1905) were likened, by the Norwegian composer Edvard Grieg, to a symphony.4 The most opulent German delicatessen of all, Dallmayr, which opened in Munich during the late seventeenth century (and is still in existence), made daily deliveries to Prince Luitpold of Bavaria. By the late nineteenth century, when the newly unified country flexed its imperialist muscles, delicatessens were also known as Colonialwaren, since most of their products were brought back from German colonies abroad. Dallmayr, for example, introduced the German public to bananas, which it imported from the Canary Islands.

France was not far behind in the realm of imported delicacies. After the French Revolution, the Israeli food and wine expert Daniel Rogov estimated, seventy royal chefs were guillotined, eight hundred opened restaurants, and no fewer than sixteen hundred opened gourmet food shops called charcuteries, which specialized in cured and smoked meats.5 In addition, many of the workers in fine luxury goods transformed themselves into purveyors of fine food and drink. According to a French scholar, Charles Germain de Saint Aubin, writing in 1795, most of the haberdashers, embroiderers, jewelers, goldsmiths, and other high-end artisans in Paris opened food stores, bars, and restaurants; he notes that they had “crowded into the center of Paris to such an extent that it [was] not unusual to find a whole street occupied by nothing but their shops.”6

By eating spiced and pickled meats, along with other gourmet foods, the Parisian bourgeoisie were able to show off their rising economic and social status, just as second-generation Jews were to do in New York a century and a half later by patronizing the delicatessens in the theater district, as we will see. Long before the birth of the overstuffed delicatessen sandwich, these meats had begun to symbolize the achievement of economic and social aspirations, of rising to an elevated status in society.

Pickled Meat in the European Jewish Diet

Cured meats and sausages entered the Jewish diet during the tenth and eleventh centuries, when Jews were living in the Alsace-Lorraine region of France. When they moved eastward in large numbers in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries at the invitation of the Polish kings, they brought along what the Yiddish writer Abba Kanter called “this-worldly articles such as Dutch herring, smoked and canned fish, . . . and German sausage.”7 Pastrami, as mentioned earlier, was a Romanian specialty; it originated in Turkey and then came to Romania through Turkish conquests of southeastern Europe, in the area of Bessarabia and Moldavia. The name seems to derive from similar words in Romanian, Russian, Turkish, and Armenian—pastram, pastromá, pastirma, and basturma, words that mean “pressed.”8 Indeed, meat was preserved by squeezing out the juices, then air-drying it for up to a month. Turkish horsemen in Central Asia also preserved meat by inserting it in the sides of their saddles, where their legs would press against it as they rode; the meat was tenderized in the animal’s sweat.

The eighteenth-century French gourmet Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin—who famously said, “Tell me what you eat and I will tell you who you are,” frequently paraphrased as “You are what you eat”—quoted a Croat captain to the effect that when his people are “in the field and feel hungry, we shoot down the first animal that comes our way, cut off a good hunk of flesh, salt it a little (for we always carry a supply of salt in our sabretache) and put it under the saddle, next to the horse’s back; then we gallop for a while, after which,” he demonstrated, “moving his jaws like a man tearing meat apart with his teeth, ‘gnian gnian, we feed like princes.’”9 The etymologist David L. Gold discovered a longer form of the word, pastramagiu, in both Turkish and Romanian, that referred to the person who both made and purveyed the salty, smoky, reddish meat. Interestingly, the ethics of the pastramagiu were suspect; it was a term also used to refer metaphorically, according to a Romanian dictionary, to a “bum, loafer, scalliwag, vagabond; rascal, rogue, or scamp.”10

Given widespread and grinding poverty, meat consumption of all kinds among eastern European Jews was extremely low; historians have speculated that the average consumption of meat per household among the Jews of Poland was about a pound a week during most of the nineteenth century, with poor families eating almost none.11 As Hasia Diner (the Hungering for America author) has noted, beef was especially expensive because of a hefty sales tax. This tax had been originally instituted by Jews themselves in order to provide funds for communal life but then taken over in many areas by the government. The despised tax, called the korobka, thrust most meat out of reach of the poor.12

In “Tevye Strikes It Rich,” the Yiddish writer Sholem Aleichem describes what happens after Tevye the Dairyman (later the hero of the pathbreaking 1964 Broadway Jewish musical Fiddler on the Roof, by Jerry Bock, Sheldon Harnick, and Joseph Stein) gives two rich Russian Jewish ladies a lift home on his wagon. The family sets out an immense banquet to celebrate their safe return. Tevye is wide-eyed, realizing that he could feed his family for a week with the crumbs that fell off the table. He is finally invited to join the feast, which includes food that he “never dreamed existed,” including “fish, and cold cuts, and roasts, and fowl, and more gizzards and chicken livers than you could count.”13

Smoked and pickled meats remained rare delicacies for most eastern European Jews well into the twentieth century. They were viewed as a special treat, as one notes in the exuberant klezmer tune “Rumenye, Rumenye” (Romania, Romania). Aaron Lebedeff, who wrote and performed the song, was the most celebrated Yiddish vaudeville star in New York in the 1920s. He punctuated his rendition with popping noises to imitate the sound of uncorking bottles for his favorite meal back in the Old Country, which comprised “a mameligele, a pastromele, a karnatsele—un a gleyzele vayn” (a little polenta, a little pastrami, a little sausage—and a small glass of wine). As the sound of the clarinet goes into ecstatic whoops, the singer recalls the pleasure of eating just a tiny bit of each of his favorite foods.14 Similarly, the painter Mayer Kirshenblatt, who grew up in the Polish shtetl of Opatow in the 1920s, noshed on corned beef only when his uncle brought it back to his own shtetl, Drildz, from business trips to a larger town, Radom.15

For wealthier Jews, pickled beef was a part of their regular diet. Hans Ullman, who grew up in northern Germany in the early years of the twentieth century, recalled the double-walled wooden shed that stood on his family’s farm and that was used to cure meats. Sawdust filled the space between the inner and outer walls of the building. In the winter, the shed was filled with ice from the mill pond, and the ice was covered with more sawdust. Beef was placed in earthenware pots, which were filled with brine and then submerged in the sawdust. After the beef was cured, it was immersed in a series of baths of fresh water to remove as much salt as possible. It was then minced by a servant girl who used a hand-cranked machine that turned the beef into meat loaf or patties.16

Geese and poultry were more available than beef, given the relative lack of grazing land in eastern Europe that was available to Jews, who were barred by the czar from owning land. In Yekheskl Kotik’s memoirs of a privileged late nineteenth-century upbringing in the eastern European town of Kamenits, the author recalled his Aunt Yokheved slaughtering up to thirty geese at once. She cured the geese in a barrel for a month and then served pickled goose meat and cracklings to everyone in her extended family.17

In eastern Europe, Jews were much more likely to own drinking places than delicatessens; indeed, according to the historian Glenn Dynner, the vast majority of taverns in Poland were leased by Jews from the nobility.18 As the memoirist Aharon Rosenbaum recalled of his hometown of Rzeszow, Poland, “There were a lot of taverns in Rzeszow. . . . Given the opportunity, men would sit down and discuss politics or municipal affairs. The best known tavern with the best mead belonged to Yekhiel Tenenbaum whose wife Khana would serve her tasty kigels [kugels, in Lithuanian Yiddish] and cholent [a hearty stew usually served on the Sabbath] to the guests.”19

While few in number, delicatessens did exist in eastern Europe. Memorial Books (Yizkor Buchs in Yiddish)—collections of records and memoirs of eastern European Jews compiled by Holocaust survivors in the 1940s after their towns had been destroyed by the Nazis—often mention delicatessens, where prepared or imported (typically canned) foods were sold. But they make little distinction between them and ordinary grocery stores, such as in an 1891 business directory from Nowy Sacz, Poland, that lists no fewer than thirteen grocery/delicatessen dealers.20 Similarly, a description of the shops next to the market square in the Ukrainian town of Gorodenka reads, “Some stores sold leather and boots, and only a few grocery stores like those of Yankel Haber and Shlomo Shtreyt met the ordinary needs of the citizens of the city. They sold a greater and colorful selection of supplies; some even sold delicatessen.”21 But what was meant by “delicatessen” is not clear.

A memoir of Jewish life in Mlawa, Poland, offers a tantalizing clue. It notes that a particular store “also served as a delicatessen. One could eat a piece of herring and polish it off with a slice of sponge cake, drink a glass of tea or a glass of soda with syrup which was measured out in small wine glasses made of white metal. . . . The Gentiles drank beer and brandy there and gorged themselves on derma and cabbage.”22 And in the town of Kelem, Lithuania, the businessman Yerachmiel Imber owned two different stores, a grocery store and a delicatessen, the latter called Vitmin. This was, in the words of the Mlawa memoirist, “a new and different type of shop in such a small town like Kelem. In it one could buy such things as candies in all varieties, tropical fruits, and other imported and fine delicacies.” In neither of these establishments, it seems, was meat on the menu.23

The Delicatessen Migrates to the New World

When did delicatessens first come to the United States? Even before the Revolutionary War, Thomas Jefferson, who was known for his epicurean tastes, lauded the gourmet food stores that he patronized in Philadelphia.24 But the first real influx of what were actually called “delicatessens” began with the successive waves of central European immigration in the mid-nineteenth century; indeed, Germans and other central Europeans became the largest ethnic group in New York. The first delicatessen owners in New York were from Germany and the neighboring Alsace-Lorraine region of France.

Among the most successful delicatessen owners was H. W. Borchardt, who had opened an iconic food store in Berlin in 1853. In the German capital, Borchardt purportedly served customers from as far away as Asia; he claimed that the sultan of Turkey employed him to cater meetings with foreign princes. Upon his arrival in New York, he opened a store on Grand Street on New York’s Lower East Side. His shelves brimmed with cooked meats, hard cheeses, fancy canned foods, imported teas, olive oil, and other high-end groceries. According to the writer Edwin Brooks, “Everything capable of making a mouth water was there—and at prices prohibitive to the average person’s pocketbook.”25

The very first use of the word delicatessen in the New York Times occurred in 1875 in the context of an amusing lawsuit. A dyer, August Rath, had fallen in love with the daughter of a German delicatessen owner named Caesar Wall. “August dyed for a living in Jersey,” the journalist quipped, “while Caesar ministered to the living in the form of sausages, sauerkraut and other delicatessen.” On a shopping trip to the store, August met Caesar’s virginal daughter, with whom he promptly fell in love, especially after being given her delicate lace jacket for cleaning. Before the nuptials were solemnized, August was invited to become a partner in the business. But when the daughter began to bestow her attentions on another man, August wrathfully withdrew both his funds and his affections.26

German delicatessen stores in New York did a brisk business, especially at Christmas time, by purveying dozens of kinds of sausages, smoked goose breast, apricot jam, honey cake, and plum duff. For an authentically German Christmas, the New York Tribune reported in 1900, a visit to a German delicatessen was essential since “it takes the German many years to become so thoroughly Americanized that he does not want the regulation German Christmas table luxuries, and these constitute the Christmas stock of the delicatessen dealer.”27

Patronizing these small, mostly family-owned German delicatessens, the New York Times journalist L. H. Robins recalled, was an exotic pleasure; indeed, “to visit them and breathe their unfamiliar good odors had the tang of an adventure in foreign parts. New Yorkers used to do it just for the thrill.” The recipes were “handed down in the old country from generation to generation of hausfrau.”28 The German section of the Lower East Side was called Kleindeutchland (Little Germany); if one went down there at daybreak, the New York Herald noted, “before it is fairly light, you will see the worthy burghers astir, opening the windows of the small delicatessen stores.”29

According to the etymologist Edward Eggleston, writing in 1894, the term delicatessen store was still used exclusively in New York, demonstrating that the English tongue, as spoken in America, had borrowed relatively few words from German at that point.30 But by the 1920s, the critic H. L. Mencken already observed the “profound effect” of the German migration on American culture, as shown by the nationwide adoption of many German words for food and drink.31 Furthermore, the delicatessen trade, like many other occupations, had a colorful, exuberant lingo of its own. The etymologist H. T. Webster reflected in 1933 that “delicatessen men,” like shoemakers and undertakers, had an occupational vocabulary that was “as little understood by outsiders as if it were Choctaw.”32

Not all delicatessens were German ones, however. In 1885, the Brooklyn Daily Eagle complained that a neighborhood food store on Mott Street in Manhattan’s Chinatown was making “no attempt to sell foods made or grown in this country, there being sold what the Germans would call a ‘delicatessen.’”33 A Chinese journalist, Wong Chin Foo, took exception to this idea that the Chinese delicatessen was in any sense inferior to a German one; he extolled the store’s “perfumed ducks, pickled oysters and beautifully roasted and powdered pigs, with pink ears and red nostrils.” Foo opined, moreover, that the Chinese delicatessen, of which there was but one for the city’s ten thousand Chinese residents, was far superior to its numerous “Caucasian” counterparts, in that the latter “always sells stale meat and rotten cheese,” while the former was known for its freshly killed pigs, chickens, and ducks. Foo insisted that while the European-style delicatessen required an initial outlay of hundreds of dollars and brought in little, the Chinese delicatessen cost a mere twenty dollars to purchase the meats and yielded “big profits.” And, he observed, an “ordinary hallway” could accommodate a good-sized Chinese delicatessen store.34

Whatever the delicatessen’s country of origin, its fare was widely perceived as exotic. A journalist for the New York Tribune who toured the food shops of the Lower East Side in 1897 found a “profusion of uncommon, foreign-looking eatables” sold in delicatessens, including smoked beef, smoked jowls, fresh ham, meat jelly, liver pudding, Russian caviar, and pumpernickel bread. These shops, the observer noted, had “gradually come to take the place of the English bakeshops,” adding that they would “roast any desired article for their patrons, from a small bird to a boar’s head elaborately decorated.” The writer singled out the kosher delicatessen shops on the Lower East Side, in which he discovered smoked goose meat of various kinds, along with potato, beet, cabbage, parsnip, and herring salads in stone crocks. The kosher delicatessen is a “source of much comfort to those who live ‘by the family,’” he explained, “and whose time is too valuable to devote to cooking.”35

Food experts picked up on the parade of ethnic edibles that were making an entree into New York. As the historian Donna Gabaccia has noted, “cross-over” eating was common in New York and other cities in the late nineteenth century, as ethnic groups avidly enjoyed each other’s cuisine.36 This tradition, as Gabaccia has found, went back to the colonial era, when the English, Spanish, Dutch, and Native Americans occasionally sampled each other’s foods.37 But by the turn of the twentieth century, according to the journalist George Walsh, a proliferation of “queer foreign foods” had surfaced in American cities to sate the appetites of recent immigrants. Walsh reflected that “the early tastes which we cultivate are hard to eradicate, and the foreigner turns to the food of his fatherland with great relish, even though coarse and unsavory compared with the food of his adopted land.”38

Walsh made no mention of Jewish delicatessens, but he limned the French, German, and Italian delicatessen shops that he discovered in New York, Philadelphia, and Chicago—stores that, he observed, had begun to attract “Americans” as well as immigrants.39 In the growing number and variety of these stores, Walsh espied blood sausage from Italy, pigs’ knuckles from France, air-dried beef from Spain, tree and sea mushrooms from Japan, dried chickens and ducks from China, cabbages from Scandinavia, tamales from Mexico, and cinnamon and clove cakes from Palestine. While he considered none of these items to be particularly appetizing, Walsh was impressed by the growing diversity of the urban food scene, in which, he conceded, “all of these odd dishes of the foreigners in our midst tend to broaden our own national bill of fare.”40

Nor was Walsh alone in omitting Jewish delicatessens from a round-up of local food stores. Forrest Chrissey, the author of a book on American food published in 1917, also overlooked them in his chapter on “tempting table delicacies” purveyed in delicatessen stores of various nations. Chrissey catalogued Hanover tea sausage from England, candied cherries and goose liver sausage from France, guava jelly from the West Indies, pimento peppers from Spain, vermicelli from Italy, birds’ nest soup from China, and even canned kangaroo tail from Australia—but no corned beef or pastrami.41

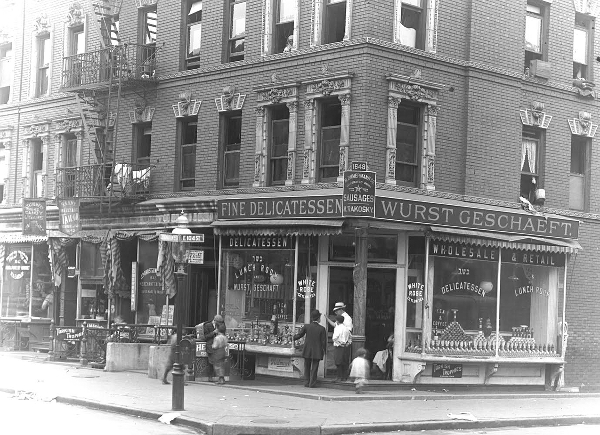

Indeed, there were relatively few kosher delicatessens in New York during the period of mass migration from eastern Europe—this despite the fact that Jewish immigrants owned a variety of mom-and-pop food businesses such as grocery stores and butcher shops. In 1899, an oft-cited survey of the Tenth Ward of the Lower East Side (which, with more than seventy-five thousand people crammed into a mere 109 acres was the most densely populated place on earth) found only ten delicatessens and ten wurst (sausage) stores—the latter likely overlapped with delicatessens to some extent in terms of their wares.42 Indeed, delicatessen stores were themselves known as wurst gesheftn—sausage stores. By contrast, there were 131 kosher butcher—schlacht, in Yiddish—shops, suggesting that most Jewish families preferred to cook their meat at home. Indeed, in the entire immigrant ghetto, there were more than a thousand kosher butcher shops, selling an impressive total of six hundred thousand pounds of kosher beef a week.43

The Jewish delicatessen was an outgrowth of these kosher butcher shops. Some kosher butchers had started selling prepared foods, displaying pickled meats and frankfurters on hooks, along with shelves of beans, ketchup, crackers, and soup.44 From the outset, the delicatessen stores tended to be long and narrow, with a counter running down one side. From this, kosher delicatessens developed, in which meats could be sliced hot, with hot dogs and potato knishes cooked on a grill in the window.

Katz’s, which opened in 1888, was perhaps the first “true” Jewish delicatessen in New York. Originally opened under the name Iceland’s Delicatessen in 1888 by two brothers of Reuven Iceland, an important Yiddish poet, the store quickly thrived. In 1903, after the Iceland Brothers were joined by Willy Katz, the store was renamed Iceland and Katz. In 1910, Willy Katz and his brother, Benny, bought out the Icelands. Redubbed Katz’s, the deli then moved across to the west side of Ludlow Street. It was soon joined by other delicatessens, both on the Lower East Side and throughout the city.

Patricia Volk, the author of the lyrical memoir Stuffed, a chronicle of her family’s life in the restaurant business, claims that her paternal grandfather, Sussman Volk, a miller from Vilna, introduced pastrami to America. Having failed to make it as a tinker, Volk left the cookware business in 1887 and opened a butcher shop on Delancey Street. A friend asked Volk to store a suitcase in his basement while he returned home to Romania for a visit. In return, he gave Volk his pastrami recipe, which Volk used to such success that he had to open a delicatessen to meet the demand.45 While Volk’s story is apocryphal, the author Marcus Ravage has corroborated it to the extent that at the turn of the twentieth century, Romanian delicatessen stores appeared with their “goose-pastrama and kegs of ripe olives and tubs of salted vine-leaves.”46

Employees of Katz’s Delicatessen standing outside the store on Houston Street in the 1930s (Courtesy of Malene Katz Padover and Marvin Padover)

Some housewives pickled and smoked their own meat at home. But the process was so complex and time-consuming that few chose to do so. The first American Jewish cookbook, published in 1871 by Esther Levy and directed mostly to upper-class German Jewish women who had servants, contains directions for doing both. To cure a piece of kosher meat, Levy explains, first “make a pickle of salt, strong enough for an egg to swim on top of the water; add some salt-petre, a little bay salt, and coarse brown sugar.”47 After boiling all of these ingredients together and skimming off the fat, the meat is pressed down in a tub for a week or two. Smoking the meat presented particular challenges for the home cook; after the meat has been pickled for exactly sixteen days, Levy directs, either “send it out to be smoked” or, if the cook insists on doing it herself, “place it over a barrel, containing a pan of ignited sawdust, for some hours every day, until nicely browned.”48

Poverty and Pickled Meat

For Jewish immigrants, the family budget dictated how much meat could be consumed. When kosher beef prices suddenly spiked from twelve to eighteen cents a pound in 1902, enraged Jewish women led a three-week boycott that began by picketing the downtown slaughterhouses. Protests erupted in Brooklyn, Harlem, Newark, Boston, and Philadelphia. Some of these were directed against delicatessens on Rivington and Orchard Streets, where rioters grabbed meat and poured kerosene on it. A few weeks later, after Orthodox rabbis also endorsed the boycott, the prices reverted to previous levels. But, as the historian Paula Hyman has written, the episode demonstrated the power that women had when they banded together; it became a model for later activism by both Jewish and non-Jewish women.49

On the whole, Jewish immigrants did eat better in America than they had done in eastern Europe. But many were still desperately poor and had few funds either for food or for the ice that was needed to keep it from spoiling.50 For example, hunger was a constant companion for the future boxing promoter Sammy Aaronson, who lived on the Lower East Side until the age of ten, when his family moved to Brownsville. “Eating was always a struggle,” Aaronson recalled in his memoir. “We lived on pumpernickel, herring, bologna ends and potatoes.” His mother sent him to a Hester Street delicatessen, where he purchased a “steering wheel”–sized pumpernickel bread for a dime. The Aaronson family enjoyed hot food on Friday night, when they enjoyed a thin meat soup from the butcher’s leftovers and bones. On Saturday nights, they scored the ends of salami, bologna, or garlic wurst or even some higher-quality meat if it were “late enough at night when the guy wanted to clean out his shelves.”51

As the historian Moses Rischin noted, immigrants were obliged to “husband” their energy, time, and money in order to eat meat for their Sabbath dinner on Friday nights.52 This often meant eating quite meager meals during the week. Those who spent their hard-earned funds on delicatessen food were castigated by social workers who tried to educate them about the importance of thrift.53 Sara Smolinsky, the protagonist of Anzia Yezierska’s autobiographical novel Bread Givers, was starving from working in a sweatshop, to the extent that, she says, “Whenever I passed a restaurant or a delicatessen store, I couldn’t tear my eyes away from the food in the window. Something wild in me wanted to break through the glass, snatch some of that sausage and corned-beef, and gorge myself just once.”54

Jewish parents’ attitudes toward food were often conditioned by their own childhood memories of want in eastern Europe. When they could, Jewish mothers routinely overfed their children, especially their sons. Indeed, providing one’s children with excessive amounts of food became ingrained in American Jewish culture. “In the swelling and thickening of a boy’s body was the poor family’s earliest success,” noted the critic Alfred Kazin. “‘Fix yourself!’ a mother cried indignantly to the child on the stoop. ‘Fix yourself!’ The word for a fat boy was solid.”55 The boy’s heft concretized the sturdiness of the Jewish family’s position in society—it demonstrated the “solidity” of their grasp of an American identity.56

Eating Out in New York

Despite the poverty of immigrants, they did enjoy eating food away from home. While delicatessens were not yet a prominent part of the urban landscape, other kinds of eateries and places of leisure were woven into the fabric of life in the city. New Yorkers went out to a staggering variety of places, including, according to the historian David Nasaw, “restaurants, lecture halls, and lodges; beer halls, bawdy houses, brothels and dance halls; billiard rooms, picnic groves and pleasure gardens located just outside the city; and thousands of concert saloons and cheap variety theaters.”57 Rather than enabling immigrants to “escape” reality, the scholar Sabine Haenni has suggested, eating out and other leisure activities furnished a useful take on reality, one that enabled immigrants to “negotiate the massive upheavals, dislocations, and disruptions attending urban immigrant modernity.”58

Buying and consuming delicatessen food was thus part and parcel of becoming American—and even, for some, of learning English. The writer Maurice Hindus, who arrived from Belarus in 1905, when he was a young teenager, learned English by taking sandwich orders from the girls who worked in a garment factory and fulfilling them at a local delicatessen. After struggling for a week, Hindus’s facility with English rapidly improved, to the extent that the well-meaning boy would “only rarely get them so badly mixed that the girl who ordered a frankfurter without mustard received a corned-beef sandwich with mustard.”59

Food also played an essential role in mitigating feelings of homesickness; as the historian Susan J. Matt has noted, “urban ethnic enclaves offered immigrants the cushion of the familiar, for the numerous grocery stores, bakeries and restaurants provided the opportunity to purchase a taste of home.”60 Matt quotes the Romanian-born author Marcus Ravage, who moved from New York to Missouri, where he “suffered unendurably from hunger” because “everything tasted flat.” He lamented that he “missed the pickles and fragrant soups and the highly seasoned fried things and the rich pastries made with sweet cheese that [he] had been brought up on.”61

There were a plethora of opportunities to eat out in New York, including inexpensive restaurants (such as the “penny” restaurants in Brooklyn, which actually sold meals for a nickel), pushcarts (which carried bagels, pickles, and other familiar eastern European Jewish items), and outdoor food stalls. Most popular of all was the candy store, with its all-important soda fountain. “Subsisting on a scatter of pennies,” the historian Irving Howe recalled, “the candy store came to serve as an informal social center in the immigrant streets.” The delicatessen, “while important,” Howe concluded, “seldom served as the center for either adolescents or grownups as the candy store did.”62

The candy store was the social center of the neighborhood. “To the boy home from work in the office or factory, and to the school boy, with nothing to do in the evening, the candy store serves as a club-house, where he can meet old friends and make new ones,” the sociologist Benjamin Reich observed in 1899. Many of these stores had back rooms that were advertised as ice-cream parlors but that also served as venues for club meetings and performances by teenager amateur comedians testing out their vaudeville routines.63

The Tenth Ward boasted more than fifty confectionary shops at the turn of the twentieth century—fully five times the number of kosher delicatessens. The playwright Bella Spewack, who moved four times during a tumultuous childhood on the Lower East Side, did not mention eating in delicatessens in her memoir, Streets, but did recall with great fondness the candy store on the corner of Lewis and Stanton Streets, where her mother bought her hot chocolate on cold winter nights.64 And while the delicatessen and candy store may have seemed quite different from each other, a bizarre combination of the two occurred at Luna Park, the Coney Island amusement park, where two German sisters named Bauer opened a “candy delicatessen” that sold marzipan versions of delicatessen products, including frankfurters, sausages, and sauerkraut.

Candy stores, the historian Jillian Gould has pointed out, were “not merely about a commodity. Rather, they were as much about the pivotal role they played within the community. . . . What happened around the store crystallized what was happening in the neighborhood at large.”65 Immigrant Jews flocked to candy stores for seltzer or soda water, known colloquially as “two cents plain.” Gould dubbed the candy store the “local communications center,” where tenement dwellers could use the telephone (at a time when few families had their own) or converse with the other denizens of the neighborhood.

Also important were coffeehouses; by 1905, according to Howe, there were “several score of these cafes, or, as they were sometimes called, coffee-and-cake parlors, on the East Side.”66 As in fin de siècle Vienna, where it was proverbial that Der Jud gehört ins Kaffeehaus (the Jew belongs in the coffee house), Jewish New Yorkers found the cafe to be a congenial haunt. For a dime, plus a nickel tip, one could order a glass of tea and a slice of cake, in an atmosphere filled with Yiddish and Hebrew writers, actors, scholars, and artists. In David Freedman’s comic 1925 novel Mendel Marantz, a successful Jewish immigrant purchases a whole tenement building on the Lower East Side, where he establishes a combination delicatessen and coffeehouse. The crowd of nouveau riches manufacturers and businessmen relax at tables with samovars; they play cards or chess, while “munching tongue and bologna sandwiches and drinking bottles of celery-tonic.”67

Fried-fish stalls, similar to those in London (which had been opened by Sephardic Jews—from the Iberian Peninsula—who appear to have invented “fish and chips”),68 also made their appearance in New York in the “tenement house districts” such as the Lower East Side. Such stands sold cooked fish, eels, oysters, or crab for a few pennies. Most immigrant Jews, of course, would have eschewed the shellfish. “Like the delicatessen store,” the New York Times observed, “these fried fish shops are a boon to the woman who doesn’t want to cook, or who for some reason or other cannot do so at a particular time.” There were only a few seats in the store, so it was assumed that the customer would take the food away. “A specially cooked order that may be taken hot to the tenement a few doors away costs a little more than cold cuts,” the Times reported, pointing out that what a restaurant would sell for a quarter retailed for no more than ten or fifteen cents at a fish stand. On the other hand, the newspaper conceded, bread was not included.69

During the 1880s, some soda fountains, which were also commonly found in drug stores, had begun to serve sandwiches and evolve into what were called luncheonettes. Luncheonettes were found not just on the street but also in department stores, dime stores (such as Woolworth’s), and railroad depots. In the first two decades of the twentieth century, luncheonettes—where customers generally sat at a counter—then evolved into lunchrooms, where table service was added. The historians John A. Jakle and Keith A. Sculle have suggested that lunchrooms were “the kind of business that many immigrant families could aspire to early in the twentieth century.”70 But they still remained tied to their origins as candy stores. For example, Schrafft’s, which began in Boston in 1898, was a candy manufacturer that opened soda fountains as outlets for its products. In 1915, it had a dozen stores in the New York area; two decades later, it boasted three dozen stores, dispersed along the Atlantic seaboard.

In competing with all these other options for dining out, relatively pricey delicatessen food was at a disadvantage, even in the Jewish community. The immigrant Jewish woman’s kitchen was her castle. Tenement apartments on the Lower East Side were structured with the kitchen literally at the center.71 It was the accepted role of a wife and mother to cook for her family, not to purchase prepared food. To take out food was a tacit admission of inferior cooking skills. It was also difficult for many Jewish women to trust that prepared food was prepared under kosher auspices. This was a reasonable fear, given repeated scandals, as we shall see, related to the manufacture of kosher food.72

Nevertheless, immigrant Jews were under pressure to change what they cooked at home to more Americanized fare. Cooking instructors in the settlement houses, where the immigrants were taught the English language and instructed in American customs, emphasized the importance of relinquishing spicy, dark, odoriferous ethnic foods in favor of bland, white, odorless American ones. Garlic, which was often used in Jewish cooking, came in for particular censure; there were long-standing prejudices, dating back to the Middle Ages, against Jews as being stinky because of the garlic that they consumed.73

Gleaming white kitchens in the settlement houses, as well as the starched white aprons in which the eager pupils were clad, reinforced the whiteness and blandness of the foods that they prepared. As the historian Sara Evans has noted, home economists working in the settlement houses extolled the virtues of “white sauce,” which she suggests, “found an analog in the concept of the American melting pot, which dissolved the pungent spiciness of diverse American cultures.”74

These attitudes against the foods of immigrant cultures made delicatessen meats a hard sell. Because the kosher delicatessen was not yet an entrenched part of immigrant life on the Lower East Side, and because the family had little capital to invest, the parents of one young Jewish immigrant, Samuel Chotzinoff, struggled to establish their delicatessen in business. The Mandlebaum Sausage Factory on Houston Street installed them in business, and a soda manufacturer lent them a soda fountain. A relative hand-lettered the curving words “Kosher Delicatessen” on the plate-glass window in the front, while an impromptu window display was concocted of salamis hung by cords from the ceiling, pieces of uncooked corned beef and pastrami, and a basket of artificial flowers. A back room behind the store was equipped with a tin clothes boiler to cook the meats. When Chotzinoff lifted the boiler’s lid, he remembered, “the fatty, bubbling water spilled over on the floor, and the delicious aggressive aroma of superheated pickled beef would mingle with and soon overpower the prevailing insistent, native, musty, dank smell of perspiring, decaying paint and plaster.”75

Everyone in the family, including the children, worked in the store. When Samuel was authorized by his parents to wait on customers, he became adept at using the slicer so that he could give “paper-thin” slices of meat to the customers and much-thicker slices for himself. But after nine months of ups and downs, including a major setback in the form of a robbery and a subsequent shake-down for protection money, the family was forced to close the store.

The delicatessen business was so competitive and the profit margin so slim that many delicatessen owners shared the fate of the Chotzinoffs. A perusal of business directories from the period shows many delicatessens going in and out of business in less than a year, as in Moishe Nadir’s short story “Ruined by Success,” in which a Jewish immigrant who opens a delicatessen store receives no customers, despite a floral wreath that he places in the window to wish himself abundant patronage.76 “For Sale—Cheap,” ran a typical classified advertisement in 1888 in the New York Herald. “A fine delicatessen and kosher wurst store, with horse and wagon and outdoor trade.”77

Rise of the Kosher Sausage Companies

Isaac Gellis had manufactured sausages in Berlin, where he won a contract with the Union army to supply beef to the troops. He arrived in New York in 1870, more than a decade before the massive exodus of Jews from eastern Europe, and opened a sausage factory on Essex Street. His secret was to use bull meat, not cow or steer as other kosher meat purveyors did. If smaller pieces of meat broke off from the large meats being smoked, he would sell these at retail. Gellis later boasted in his advertisements that he had helped Jewish immigrants to adjust to life in America by providing “good, real, kosher meat products.”78 Gellis was the only major manufacturer in New York—there were midwestern companies such as Vienna Beef, Sinai Kosher, and Oscherwitz that had started in the late nineteenth century—until Hebrew National began to capture an increasing share of the market for processed kosher meat.

Hebrew National was founded in 1905 by a Russian immigrant named Theodore Krainin, who had arrived in New York in the 1880s. Isadore Pinckowitz (later known as Isadore Pines), a meat peddler, bought the company in 1928 and began manufacturing hot dogs and sausages on the sixth floor of his tenement house at 155 East Broadway. The company soon opened its own retail stores. When Motl, the hero of Sholem Aleichem’s picaresque Yiddish novel Motl Peyse dem Khazns (Motl Peyse, the Cantor’s Son), immigrates with his family to America, he describes how his brother, Elye, gets a job selling “haht dawgz” for the “Hibru Neshnel Delikatesn,” which “has stores all over town. If you’re hungry, you step into one and order a haht dawg with mustard or horseradish.”79

A corner kosher delicatessen in 1911 in East Harlem, on Lexington Avenue and East 104th Street (Courtesy of Brian Merlis / Brooklynpix.com)

Hebrew National’s main competitor, Zion Kosher, emerged in the years after the First World War when the entrepreneur Max Anderson, who was peddling meat, pickles, and sauerkraut to delicatessen stores, decided to open up his own meat factory. He and his partner, Leo Tarlow, launched a company called Always Tasty (after the first initials of their last names) that manufactured nonkosher meat. They eventually decided to go into the kosher meat business, first by renting space in an old seltzer factory and then opening their own factory in the Hunts Point section of the East Bronx.

Hebrew National and Zion Kosher jostled for market share with a growing number of smaller kosher provisions companies. Indeed, by the 1930s there were more than a dozen different, independently operated kosher sausage companies located on the Lower East Side, near the slaughterhouses where they purchased their meat, including Schmulka Bernstein’s, Jacob Branfman, Barnet Brodie, Hod Carmel, European Kosher, Gittlin’s Kosher Provisions, Isaac Gellis, Hygrade, National Kosher, Remach Kosher Meat Products, Mt. Sinai Kosher Provision Supply, Ukor, and 999 Real Kosher Sausage. The delicatessen industry grew fast in order to meet ever-increasing demand for its products. Each company advertised itself as offering the highest quality and most sanitary meats under the strictest rabbinical supervision. As a Yiddish-language ad for Barnet Brodie put it, the company’s products were “made from the best meats,” were “under the supervision of the rabbis of Greater New York,” and were, last but not least, “famous for their taste and quality.”80

A Store Becomes a Restaurant

At the turn of the twentieth century, some delicatessen stores installed tables, either inside or out on the sidewalk. For example, the delicatessen store owned by Chotzinoff’s family had only three tables. At the grand opening, the relatives who were occupying the tables started to get up to let some of the bona fide customers sit down; Chotzinoff’s father waved them back down again, under the logic that the more crowded the store seemed, the better it would be for business. Meanwhile, the delicatessen counter did a booming business.

Was a delicatessen with tables a store or a restaurant? This was a question that even the courts had a difficult time answering. In a case before the New York Supreme Court in 1910, a delicatessen owner on the Lower East Side sued a fellow business owner who opened a restaurant next door to her store; the new neighbor argued that because his establishment had tables, it was a bona fide restaurant, not a delicatessen. The judge decided that a delicatessen could indeed have tables; he pointed out that delicatessens could come in all types, comparing them, “in their infinite variety,” to Cleopatra!81

This issue bedeviled even the kosher delicatessens that spread outside the city; the owners of one in Scranton, Pennsylvania, in 1914 were sued by their landlord for conducting a restaurant, in violation of the terms of their lease, because they occasionally permitted customers to sit at the family table at the rear of the store. The judge decided that their establishment could not be considered a restaurant; he found that the “agreement between the parties with respect to conducting a kosher restaurant is not violated by the selling of dried fish, frankfurters, or other articles usually kept in a delicatessen store, even though such articles are eaten upon the premises by the purchasers.” He compared the situation to one in which customers purchase cold snacks in a country store and consume them in the building, cracker-barrel style.82

With or without tables, delicatessens became targets of a nationwide campaign to enforce Sunday closing laws. According to the historian Batya Miller, the last two decades of the nineteenth century witnessed the rise of evangelical and social-reform-minded Protestants, who deemed it their religious obligation to force others to observe the Sabbath.83 This was supported by the U.S. Supreme Court, which in 1885 ruled that a Chinese laundryman in San Francisco could be compelled to close his shop on Sundays, under the rationale that the government has a right “to protect all persons from the physical and moral debasement which comes from uninterrupted labor.”84

These laws, which date back to the early seventeenth century in Virginia, required that businesses be closed on Sundays in observance of the Christian Sabbath. (They were called “blue laws” since they were written on blue paper in New Haven during the colonial era.) They posed a significant problem for many Jewish business owners throughout the country; if they were closed on Saturday in observance of their own Sabbath, then closing on Sunday deprived them of essential weekend business. Even if they were not formally prosecuted, Jewish storekeepers were often the victims of police extortion if they refused to obey the Sunday closing law.85

More than 150 owners banded together in 1895 into a formal association of delicatessen dealers to prevail upon the city to allow them to remain open on Sundays. Police Commissioner Theodore Roosevelt informed them that they could sell their products until ten o’clock in the morning—when church services typically began—and could fill deliveries throughout the day if they had been received before that hour. This pleased most of the butchers and grocers, who were happy to have the day off; they argued that anyone who needed provisions for the day could purchase them before ten o’clock. But the delicatessen dealers, especially those who owned smaller neighborhood stores, explained that they needed to stay open all day on Sunday in order to serve their less affluent customers who did not own refrigerators.86

Few delicatessen owners were pacified by Roosevelt’s making an exception for delicatessens that had tables in their establishments. But they got a sympathetic hearing from Excise Commissioner Julius Harburger, who fulminated against the Sunday law, informing the delicatessen owners at a public meeting in July 1895 that their stores “are a necessity to the people; they are part of the people; they are the existence of the people.”87 His rhetoric became even more overheated in a speech a month later to his constituents, declaring that “under monarchical forms of government, under despotic powers, the people are not hampered, molested, or coerced, as we are under the restrictive policy of the Sunday law,” which, he said, led to “the discomfort of three-quarters of our city’s population, and the loss of millions of dollars.”88

Sunday closing laws nevertheless continued in effect, with protests continuing for years. In 1899, the editor of the New York Times sympathized with the delicatessen owners, and he penned a series of ringing editorials in their defense. The first noted that Sunday was the biggest day of the week for the delicatessen trade. “Everyone who lives in New York knows that it is the custom of some nine-tenths of the householders of New York, not alone of German birth, to give their servants Sunday evening off, and on that day to skirmish, as it were, for their evening meal.”89

After lambasting the statute that prevented the consumption of delicatessen food on Sundays in the metropolis. the editor spoke up for the “scores, if not hundreds of thousands,” of New Yorkers who purchase food from delicatessens on Sundays. Nor, he pointed out, can city dwellers necessarily buy the food ahead of time, since “Sunday is their visiting day. If unexpected visitors arrive and there is ‘nothing in the house,’ the dispatch of a messenger to the dealer in cooked food is the natural and ready recourse of the host and hostess.”90 An advice columnist declared that a housewife would be appropriately frugal if she would “fit up her reserve shelf against the coming of the unexpected guest, and so forestall the hurried trip to the delicatessen store, which is such a drain on both time and pocketbook.”91

The government also recognized that exceptions needed to be made. A bizarre compromise was worked out February 1899 in which the delicatessens could remain open on Sundays if, like caterers, they sold only complete meals, rather than uncooked food or individual items. Thus, delicatessens would refuse to sell a package of meat by itself, but if a loaf of bread were added to the order, then the sale could take place.92 Furthermore, if customers desired to carry out the food, then they were obliged to pretend that the delicatessen was delivering it to them, agreeing to act as the agent of the store in bringing it home! After considerable wrangling over the next several months, the courts finally relented, permitting delicatessens to purvey cooked food on Sundays. Two hundred euphoric delicatessen owners celebrated their victory in a park in Upper Manhattan.93

Interior of Youngerman’s Delicatessen on Marcy Avenue in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, in 1918 (Courtesy of Brian Merlis / Brooklynpix.com)

Nonetheless, the delicatessen raids resumed in 1913 under the direction of Rhinelander Waldo, Tammany’s corrupt police commissioner. These were more successful, since the delicatessen dealers were induced to participate by being made “delicatessen deputies,” which enabled them to spy on their competitors and have them served with summonses. Again, only “prepared” food could be sold; it was left up to the policeman on the scene—who was often obliged to rely more on his taste buds than on the statute books—to decide what constituted this type of edible. But rather than having to close all day on Sunday, delicatessens were permitted to remain open before 10 a.m. and from 4 p.m. to 7:30 p.m., in order to capture the lucrative Sunday-evening dinner trade.

The tide was turning in terms of American eating patterns. The home-cooked Sunday dinner, a staple of American life, especially for rural, churchgoing families, had largely been transformed, in the urban setting, into a take-out delicatessen meal. In 1920, an anonymous social critic in Life magazine satirically compared a typical 1890s Sunday-school picnic to one of his own day; he contrasted the earnest “packing of the [homemade] chicken sandwiches and the frosted cake” in the earlier period to his own generation’s lackadaisical, last-minute visit to the delicatessen.94

Cleanliness, Sin, and the Kosher Delicatessen

Some Jews, however, resisted the incursion of delicatessen food into their diet. While elderly immigrants, by contrast, “frowned on delicatessen and clung to their accustomed boiled and sweet-and-sour meats,” according to Samuel Chotzinoff, the younger generation “took to delicatessen for its spiciness, preferring it to the bland, boiled meats their mothers served at home.”95 Eating delicatessen food could be, for these younger Jews, a rebellious act. The critic Alfred Kazin noted that the pungency of delicatessen sausages carried, for him, an erotic charge. “Wurst carried associations with the forbidden, the adulterated, the excessive, with spices that teased and maddened the senses to demand more, still more.” Only on Saturday nights, when the holy Sabbath gave way to the profane weekday, could this food “be eaten with a good conscience.” Indeed, this was food that was “bought on the sly” and was “supposed to be bad for us”—associated with the fact that it was “made in dark cellars,” far from the light of day.96

While the spiciness of delicatessen meats may have been a boon to some customers, spices had been, since the mid-nineteenth century, the object of opprobrium in American culture. Progressive reformers had found that spices were frequently used to disguise the fact that food was spoiled or tainted. Furthermore, there were long-standing associations between the eating of spicy foods and excessive drinking. John Harvey Kellogg, founder of Kellogg’s cereal company, and his wife, the temperance advocate Ella Eaton Kellogg, insisted that the ingestion of spices and condiments led inexorably to a craving for alcohol. The association stemmed, perhaps, from the practice of placing bowls of spices on the counters of saloons; patrons chewed them to mask the smell of alcohol on their breath.

As Ella Kellogg opined in her popular cookbook Science in the Kitchen, “True condiments such as pepper, pepper sauce, ginger, spice, mustard, cinnamon, cloves, etc. are all strong irritants” that are “unquestionably a strong auxiliary to the formation of the habit of using intoxicating drinks.”97 Following the theories of an influential Presbyterian minister, Sylvester Graham (the inventor of Graham Crackers), the Kelloggs also feared that eating both meat and spicy food with any regularity would lead to sexual fantasies and masturbation; John Kellogg developed Corn Flakes in order, he declared, to promote sexual abstinence.98

Delicatessen owners throughout the country were thus obliged, from time to time, to confront the widespread perception that their fare was both unhealthy and unclean. The social worker Lillian Wald, who founded the Henry Street Settlement House, instructed immigrant Jewish mothers to refrain from serving smoked and salted meat to their children and to feed them fresh fruits and vegetables instead. A dietician who visited a kosher delicatessen in an unnamed western city in 1928 was shocked by the gluttony that she observed, noting that one obese female customer would “make a good addition to the growing army of Jewish diabetics,” and she fantasized about pulling the woman’s son out of the delicatessen and into a healthier, more rural place—where he could be furnished with less salty, sugary, and fatty victuals.99

While the cleanliness of the deli was also highly suspect, these concerns could be allayed, delicatessen owners were told, if they dressed in the proper clothes. In the pages of the Mogen Dovid Delicatessen Magazine, the main trade journal for the delicatessen owners in New York, store owners were reminded that anyone handling or serving food was compelled, by municipal legislation, to wear white. An organization called the Sanitation League informed the dealers, quoting a former city health commissioner who had been elected to the U.S. Senate, Royal S. Copeland, that “the man who is slovenly and who makes a poor appearance because of improper uniform or clothing, is sluggish and inefficient mentally and physically.” According to Copeland, “if you compel workers to wear clean ‘spic and span’ uniforms or outer garments, you improve their morale as well as their disappearance [sic]. . . . It is thus of real importance to all distributors of food or drink to ‘trade up’ in the matter of the appearance of their men.”100

Kosher meat companies and delicatessens competed to offer the products that were seen as the cleanest and healthiest. In a Yiddish advertisement in the Mogen Dovid Delicatessen Magazine in August 1931, Barnet Brodie trumpeted its “modern, sanitary factory” that produced corned beef, tongue, pastrami, salami, bologna, and frankfurters that were not just “famous for their taste and quality” but that were supervised by the rabbinical authorities in the city.101 Krainin, the founder of Hebrew National, lamented in an article in a popular magazine, the Jewish Forum, that no rabbi had seen fit to explain to the general public that the kosher laws prohibited the consumption of meat from unhealthy or diseased animals; Krainin defined this as the essence of the kosher system.102 Indeed, the Chelsea Delicatessen, located on Ninth Avenue between Twenty-Second and Twenty-Third Streets, advertised itself as providing “Cleanliness, Quality and Service Above All” in the furnishing of “sandwiches and salads of all cuts and preparations”—cleanliness came first, and everything else followed in its train.103

Balancing out the reputedly unhealthy qualities of delicatessen food, along with its fattiness and saltiness, was the drink of choice that accompanied it. Dr. Brown’s Cel-Ray Tonic was first distributed (according to company lore) in 1869 by a doctor who gave out spoonfuls to children on the Lower East Side to help alleviate their digestive problems. The bright-green soda was sold only in delicatessens until the 1980s, when it became available in supermarkets. (The name was changed to “soda” in the 1920s when the government, which was cracking down on the sale of patent medicines, objected to the use of the word “tonic.”) In addition to the use of celery in treating physical ailments, it was also widely employed to reduce anxiety. A Victorian “guide to life,” published in 1888, recommends that all people who are “engaged in labor weakening to the nerves should use celery daily in the season, and onions in its stead when not in season.”104 The food writer Leah Koenig has pointed out that carbonated beverages, in general, reminded customers of the hot-spring health spas that used mineral water to relieve both physical and psychological distress.105

Popular culture also depicted delicatessen food as unhealthy. A mean-spirited 1920s vaudeville monologue, “In the Delicatessen Shop,” features a delicatessen owner with a very heavy, mock-Yiddish accent who tries to cater to her customers’ needs while attempting to control a brood of children who are playing games with the food, as well as putting both the cat and the baby inside the counter. “Mine gracious! Izzy! Such a poy!” she finally bursts out. “Coome vrum dot counter behind. Vhen papa come he should spunish you vit a stick. How you oxpect your mamma to zell to de gustomers vhen dey seen you rolling dem epple pies on de floor around?”106

This was a routine almost certainly written for non-Jewish entertainers known as “Hebrew” comics who traded on anti-Semitic attitudes.107 The food sold in the delicatessen is portrayed as not fit for human consumption, just as Jews were typically portrayed as unsuitable for participation—unkosher, one might say—in American society. The Jewish deli owner is a laughing stock, her products—and her very personhood—irrevocably tainted. As the historian Matthew Frye Jacobson has noted, Jews were disparaged as racial outsiders who had the potential to pollute the racial stock of America.108

These stereotypes made Jews themselves unpalatable to “native” Americans; one commentator at Harvard University in the early 1920s justified strict quotas on Jewish admissions by calling Jews an “unassimilable race, as dangerous to a college as indigestible food to man.”109

Fraud in the Kosher Delicatessen Industry

Beyond the kosher delicatessen industry’s doubtful reputation for the healthfulness and purity of its products, it was also tainted by large-scale scandals that erupted around the selling of nonkosher meat as kosher. Since kosher meat was more difficult to obtain and always commanded a higher price than nonkosher (treyf, in Yiddish) meat, meat companies and delis often misled their customers by switching the two. At a time when kosher meat was in tremendous demand—in 1917, the national consumption of kosher meat reached 156 million pounds—there was big money in this kind of scam. Individual rabbis gave their hecksher or stamp of approval to the process under their supervision. Yet in 1925, a study by the state found that fully 40 percent of meat sold as kosher in New York City was actually treyf.110

It is little wonder, though, because until 1916, when the Union of Orthodox Rabbis forbade the practice, it was not uncommon for both kosher and nonkosher meat to be manufactured in different parts of the same factory. But when companies decided to produce only kosher meat, they often cut corners regarding the supervision of the process. Such was the case with Sunshine Provision Company, which switched in 1922 from the production of nonkosher meat to kosher meat but was found using hog casings for its “kosher” sausages; fully 95 percent of the meat that the company was selling as kosher was actually treyf.111

The most egregious case of fraud occurred in 1933, when the owners of one of the most prominent kosher meat companies, Jacob Branfman and Son, were indicted for selling nonkosher meat, which was delivered to the factory late at night, after the kosher supervisor (the mashgiach) had gone home. An undercover investigator testified that he had observed through binoculars as a worker draped oilcloth over the Branfman name on one of the company’s trucks while barrels of nonkosher brisket were being loaded into it. A police raid found two and a half tons of nonkosher meat sitting in the factory.112 When the case came to court, the judge ruled that “to expose for sale” means “to have in stock,” even if the product is not displayed.113 The conviction meant that not only did delicatessens have to discard all the meat they had purchased from Branfman, but rabbis instructed thousands of customers to throw out all the cooking vessels, dishes, and silverware that had come in contact with the offending products.

Delicatessen owners also often tried to trick their customers by passing off nonkosher meat as kosher; they thus saved the hefty price difference between the two types of meat. Some played on the similarity in Hebrew between the words for “kosher” and “meat”—the two words vary only by their initial letter (and even those initial letters look very similar). Rather than offering “kosher meat,” then, some delicatessen owners fooled customers by putting “meat meat” in their windows; they knew that few customers would notice the subtle difference, and they could deny that they had offered kosher meat for sale in the first place. The editor of the Mogen Dovid Delicatessen Magazine defended the practice, arguing that if stores use Hebrew lettering or put a Star of David in their window or print advertising, it is simply because they “mean to advise that Yiddish may be spoken in their places, that a Jewish atmosphere prevails, etc.” To require that Hebrew lettering must not be used in a deceptive manner, he argued disingenuously, suggests that Jews are unfamiliar with their own language.114

A revised law then required meat dealers to label their products “kosher” or “on-kosher” with four-inch signs and to display additional signs in their windows making clear which type of meat was offered for sale. These laws complemented the existing consumer-protection statutes, first passed in 1915 and upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court ten years later, that stated that it was illegal for a food dealer to represent goods as kosher when they were not.115 As an English-language editorial in the Yiddishes Tageblatt demanded in 1922, as yet another bill was proposed to regulate the advertising and selling of kosher meat, “butchers, provision and delicatessen dealers who display the word ‘kosher’ must live up to that sign.”116

Some delicatessen owners kept up the battle; they argued that the word kosher was difficult to define and can admit of a range of meanings, beyond only the strict Orthodox interpretation. For example, many delicatessens remained open on the Jewish Sabbath, in violation of Jewish law. Even if the meat itself were strictly kosher, selling it on the Sabbath rendered it impure in the minds of traditional Jews. When the state decided to continue to rely on the guidance of Orthodox rabbis and laymen to define “kosher,” more than four hundred kosher delicatessen owners joined in a protest meeting in Brownsville. The owners complained that the new regulations were reminiscent of the despised Russian korobka, and they accused the legislature of kowtowing to a small segment of the Jewish community at the expense of the majority of Jews in the city.

Samuel Caesar, the president of the kosher delicatessen owners’ association, reminded the union men at the rally that most of them were members of the Workmen’s Circle, a fervently socialist Jewish organization. How, Caesar thundered, could the owners permit a “small group of rabbis the right to force Orthodox Judaism” on them? In defining the kosher delicatessen owners as secular Jews battling against the forces of religious Orthodoxy, Caesar insisted on the delicatessen as a place where different understandings of Jewishness could coexist.117

This redefinition of the delicatessen in secular terms foreshadowed the development of the delicatessen into a kind of “secular synagogue” for second-generation Jews—one in which the delicatessen transcended its immigrant Jewish origins. As we have seen, the delicatessen, which had been largely unknown in eastern Europe, was also not particularly entrenched in Lower East Side immigrant Jewish life. At the same time, Jews were themselves marginalized by other Americans. In the next chapter, we will see how Jews began to conquer their pervasive sense of inferiority by turning Jewish delicatessen food from a low-class, suspect item into a high-class one of glitz and glamor.

As the delicatessen continued to gain traction in the culture of New York, different orientations toward Jewish religion and culture would produce not just different kinds of kosher delicatessens but a “kosher-style” type of delicatessen as well that reflected the desire of many Jews to create a new balance between their Jewish and American identities, one in which the nature of Jewish food itself would be redefined to serve the purpose of acculturation into American society.