2

From a Sandwich to a National Institution

Delicatessens in the Jazz Age and the Interwar Era

In the Marx Brothers’ first Broadway show, I’ll Say She Is!, which catapulted the vaudeville performers to stage (and later film) stardom, the delicatessen played a starring role. The 1924 revue was about a bored rich girl who promises her hand in marriage to the suitor who gives her the greatest excitement. The climax featured Groucho as a famous French hero. Playing Napoleon to Lotta Miles’s Josephine, Napoleon was surprisingly, anachronistically, and quite bizarrely fixated on Jewish delicatessen foods:

Napoleon: Get me a bologna sandwich. Never mind the bologna. Never mind the bread. Just bring the check. Get me a wine brick.

Josephine: Oh! It’s you. I thought you were at the Front.

Napoleon: I was, but nobody answered the bell, so I came around here.

Josephine: Well, what are you looking for?

Napoleon: My sword—I lost my sword.

Josephine: There it is, dear, just where you left it.

Napoleon: How stupid of you. Why didn’t you tell me? Look at that point. I wish you wouldn’t open sardines with my sword. I am beginning to smell like a delicatessen. My infantry is beginning to smell like the Cavalry.1

What makes this skit deliciously ironic is its presentation of a “Jewish” Napoleon. After all, it was the great French leader who helped to emancipate the Jews, offering them French citizenship in return for their promise to keep their religion to themselves. This enabled the rapid assimilation of most of the Jews of France and also served as a model for other European governments in their approach to the “Jewish Question”—the problem of how to integrate Jews into European civil society. In return, Napoleon became a staple of Jewish folklore.2

By contrast to this victorious bigwig, the demasculinized Groucho Marx version of Napoleon can’t keep track of his sword, and he doesn’t seem to know where he is going. Even when he finds his sword, he discovers that his presumably unfaithful lover has been using it, quite promiscuously, as a can opener. He’s “hot” for Josephine, but his body smells like a delicatessen. He is sinking inexorably back to his “Jewish” roots, which put him at odds with his role as a French hero and lover. The call of the delicatessen is ultimately too strong; after this repartee, he gestures to the band leader to strike up the famous French song “The Mayonnaise”—a joke, of course, on the French national anthem, “La Marseillaise.”

The call of the delicatessen likewise reverberated stentoriously for the children of Jewish immigrants who acculturated into American society during the Jazz Age and for whom the Jewish eatery and its fare became symbols of success. Rising prosperity after the First World War led to the pell-mell exodus of Jews from the Lower East Side. Newer Jewish neighborhoods sprang up in Harlem, the Bronx, and Brooklyn—neighborhoods in which the delicatessen became a crucial gathering space for a generation of lower-middle-class Jews who were eager to participate in American society while still maintaining loyalty to their ethnic roots.

Even as the membership of the Ku Klux Klan peaked, Henry Ford fulminated against Jewish “control” of American banking and entertainment, and stringent new immigration restrictions were passed that essentially ended the influx of eastern European Jews, second-generation Jews found a congenial gathering place in the delicatessen, a place where they could feel, in Deborah Dash Moore’s influential phrase, “at home in America,”3 and where they could congratulate themselves on having transcended their immigrant origins. The ability to consume meat was, as we saw for the bourgeoisie in late eighteenth-century Paris, a visible index of upward mobility. The sandwich-making business, in particular, appeared to be a quick route to riches. “There are sandwich impresarios in every city in the country,” the drama critic George Jean Nathan asserted, “who—up to a few years ago poor little delicatessen dealers—now wear dinner jackets every evening and own Packard Sixes.”4

The serving of “overstuffed” sandwiches in theater-district delicatessens presaged the contemporary hot-dog-eating contests sponsored annually by Nathan’s on the Fourth of July, which, like the Thanksgiving feast, are a celebration of American bounty and excess.5 The anthropologist Robert Abrahams has suggested that American holidays are typically marked by taking ordinary things and “stylizing them, blowing them up, distending, or miniaturizing them”—he lists the “lowly firecracker, the balloon, the wrapped present, the cornucopia, the piñata, the stuffed turkey, and Santa’s stuffed bag.” The overstuffed delicatessen sandwich could certainly be added to that catalogue of cartoonish items that burst their boundaries, release repressed energies, and create a carnival atmosphere of raucous celebration.6

The exaltation felt by second-generation Jews that they had finally “arrived” in America was spurred by the very atmosphere of the nonkosher, theater-district delicatessens, which were imbued with the glitz and glamor of celebrity—as shown in everything from the showbiz pictures on the walls to the sandwiches that were named after the theater and film stars of the day. Allan Sherman and Bud Burtson’s unproduced 1947 musical The Golden Touch satirizes the stardust atmosphere of these delis; it revolves around a nonkosher delicatessen in the theater district called Cheesecake Sam’s that caters to “upscale” customers such as “the most important shipping clerks and celebrated soda jerks! A boulevardier from Avenue A! The distingue of Rockaway! A furrier from Astoria.”7

The Stage Delicatessen, which opened in 1935, was thus aptly named; it was the Jewish customers who used it as a platform to display, through conspicuous consumption of large quantities of pickled meat, their own growing visibility in American society; the Stage Delicatessen’s unofficial slogan was “Where Celebrities Go to Look at People.”8 Its clientele imbibed the show-business atmosphere like slabs of brisket soaking up barrels of brine on their way to becoming corned beef and pastrami. As the vaudevillian Joe Smith joked in one of his routines, “Max’s Stage Delicatessen,” the food was “so high-class that if you get an ulcer from eating here, it’ll have on a tuxedo.”9

At these vibrant, humming eateries, ordinary New Yorkers hobnobbed with the rich and famous. Harpo Marx described the lively crowd at Lindy’s and Reuben’s as a mix of the down on their luck with the very successful—“cardplayers, horseplayers, bookies, song-pluggers, agents, actors out of work and actors playing the Palace, Al Jolson with his mob of fans, and Arnold Rothstein with his mob of runners and flunkies. The cheesecake was ambrosia. The talk was old, familiar music.”10 Second-generation Jews dined amid that lively “music” in order to have some of the stardust rub off on themselves.

It may seem odd that the humble sandwich epitomized life in New York during the opulent, ostentatious Jazz Age. But sandwiches were all the rage. The drama critic George Jean Nathan reported in 1926 on the “sandwich wave” that had “latterly engulfed the Republic.” He found 5,215 stores in New York City alone that specialized in sandwiches, which he discovered had become “one of the leading industries of the country, taking precedence over soda-water, candy, chewing gum, and the Saturday Evening Post.” Furthermore, the sandwich appealed, in one form or another, to everybody, in every social class and occupation in society, including, Nathan noted, to “the shopgirl and the lady of fashion, the day-laborer and the Brillat-Savarin.” As a result, Nathan found no less than 946 different kinds of sandwiches, made from ingredients ranging from snails to spaghetti.11

Cover of Reuben’s menu with caricatures of stage and film stars—note the slogan in the lower lefthand corner. (Collection of Ted Merwin)

The menus in the theater-district delicatessens were typically very long, with hundreds of items available every night. As Jim Heiman pointed out in his history of twentieth-century American menu design, “being handed an oversized bill of fare became an event in itself, subtly suggesting a restaurant’s importance by the seemingly endless choices offered to a customer.”12 It made the customer feel important too, to know that his or her options were so vast; the composer Oscar Levant once jokingly asked a waiter at Lindy’s if he could take a delicatessen menu home, in order to give him something to read.13

During the 1920s, which the novelist and historian Jerome Charyn calls the “delicatessen decade,”14 Jewish eateries participated in this culture of conspicuous consumption. “If you take a glance into the plate-glass window,” noted the humorist Montague Glass of a delicatessen in downtown Manhattan, “you will see such a display of food, tastefully decorated with strips of varicolored paper,15 as Rabelais might have catalogued for one of Gargantua’s heartier meals.” The turkeys, he added, are “interspersed with spiced beef, smoked tongue, plump kippered white fish, and festoons of frankfurters.” Glass compared the decor to that of an old-fashioned Pullman railroad car, which employed such expensive materials as inlaid mother of pearl, stained glass, satinwood, and mahogany.16

Some delicatessen exteriors were even more attention grabbing and ostentatious. Arnold Manoff, a worker for the Federal Writers’ Project who interviewed Arnold Reuben in 1938, compared the interior of Reuben’s with the opulent lounge of the Radio City Musical Hall, noting that as the pedestrian strolls up Fifty-Eighth Street toward Fifth Avenue,

suddenly the wall of brick to your left is ended and the periphery of your eye catches a huge pane of glass curtained in cream folds and shrubberied formally at the bottom. A red blazing neon sprawls over the window REUBENS. Typical. This is REUBENS! Who is Reuben that his name should stand alone without a word of explanation, without even a first name, without a Company or Inc after it? What the hell! You don’t mind GENERAL MOTORS; Money! Power! Industry. Well, all right, REUBEN. Twenty Five feet long, five feet high on 58th Street, Right next to the Savoy Plaza, the Sherry Natherland [sic]. Nearby Central Park, the old Plaza, Fifth Ave. Nearby Park Ave. A ritzy restaurant, if you judge by what you can’t see from the outside.17

The immense neon sign connoted brashness and brazenness, opulence and ostentation; it joined in the nightly visual symphony of the lights of the skyscrapers of Manhattan. The delicatessen’s location among the iconic hotels that surround Central Park also places it in the most august company imaginable—old-money, Protestant New York society. To the writer, there was evidently something incongruous about such an obviously Jewish name being so prominently emblazoned on the midtown Manhattan scene, at a time when Jews were still viewed by many as grasping, ill-mannered interlopers in American society. Yet the sign still suggested that a Jew and his restaurant had, however improbably, reached the pinnacle of American society.

During the Jazz Age, Broadway was itself at its zenith. The number of new shows more than doubled from 126 in 1927 to 264 in 1928—the all-time peak.18 Theater tickets were relatively inexpensive; many New Yorkers attended theater on a weekly basis, and they also patronized the palatial movie theaters that were also located near Times Square.

No ethnic group was more involved and invested in popular culture than were the Jews, who provided the lion’s share of the creative talent, financial backing, and real estate for the entertainment business.19 And no New York eateries were more emblematic of show-business culture than were the theater-district delicatessens, which transformed the ordinary sandwich into a fancy meal. According to Rian James, who penned a popular dining guide to New York in 1930, Reuben “raised the in-elegant dime sandwich to a wholly elegant dollar status!” James noted that in Reuben’s, you can “see all Broadway parade before you.”20

After his performances at the Winter Garden Theater, the famous Jewish singer Al Jolson, the most popular Jewish entertainer of his day (best known for his 1927 film The Jazz Singer), would invite the entire audience to accompany him to Lindy’s for a pastrami sandwich. The bootlegger Arnold Rothstein, infamous for fixing the 1919 World Series, did all his business at delicatessen tables at Lindy’s, where he was such a fixture that when he was gunned down outside the restaurant in 1928, many people thought that he had been an owner of the restaurant. By controlling the city’s underworld from his table at Lindy’s, the historian Michael Alexander has noted, Rothstein demonstrated that a Jew could be influential and admired, despite being a criminal, while remaining squarely within his own ethnic milieu.21

The owners of these delicatessens were colorful and obsessed with public attention. By promoting the image of their restaurants as filled with stars of every description and a general air of comic mayhem, they seemed to have themselves missed their calling to be on the stage. Arnold Reuben, for example, was described as having an “aggressive, brusque appearance” with a twitching face, from which “words roll out of his mouth in a spitting, swishing thick torrent. . . . Intonations mixed Yiddish, Broadway wise guy, clipped executive style, and big-man, really boy-at-heart, petulant, lisping, ain’t-I-charming manner.”22

Max Asnas, who opened the Stage Delicatessen in 1937 after a stint as a counterman at the Gaiety, was a short, rotund man with a waddling gait and deep voice overlaid with a thick Yiddish accent. The “sage of the Stage” was known for his quick comebacks. When the comic Jack E. Leonard accused one of the waiters of spilling mustard on his expensive coat, Asnas retorted, “You think this is cheap mustard?” An elderly female patron who asked if the establishment was kosher was told that it was so nonkosher that even when Asnas bought kosher meats, he sold them as nonkosher. “And where did you get the accent?” she pursued. “This I got from the customers,” he rejoined.23

Asnas, who spent much of his time at the racetrack, was, despite his diminutive height, larger than life. The former Hollywood press agent Leon Gutterman called Asnas a “philosopher, philanthropist, comedian, gag expert, show business critic, psychologist, psychoanalyst, and ‘pastrami pundit’ all in one man.”24 Everybody who was anybody, it seemed, knew him. In “When Mighty Maxie Makes with the Delicatessen,” a song written by the Broadway composer Martin Kalmanoff, Asnas is proclaimed the “toast of the town,” and the Stage, it is noted, is where “you’ll find debutantes with poodles eatin’ hot goulash and noodles” and where the “corned beef and pastrami can keep them all fressin’ [gobbling] till it’s time to close down.”25

The length of a delicatessen menu was matched by the extravagance of the dishes. A sample menu from Reuben’s Delicatessen from the 1920s begins with a selection of oysters, clams, and other shellfish, then proceeds to a section on hors d’oeuvres that features beluga caviar and pâté de foie gras. After a “Steaks and Chops” section that lists pork chops along with lamb chops and chateaubriand, the menu offers various kinds of ham and rarebit. Even a humble Jewish favorite such as matzoh brei (a matzoh and scrambled egg combination, traditionally eaten during the week of Passover, when the consumption of leavened bread is forbidden) was gussied up as Matzoth Pancakes with Jelly a la Reuben, while chopped liver was reinvented as Chopped Chicken Livers with Truffles and Mushrooms. In addition, more than two dozen “named” sandwiches are also listed on the menu, each costing about a dollar. Beginning with the Al Jolson Tartar Sandwich, which paid tribute to the greatest Jewish star of the era, the menu includes sandwiches named after the playwright Sammy Shipman, the silent film star Lina Basquette, and the orchestra leader Paul Whiteman.

Reuben claimed that when he created a sandwich, he tried “to make it fit the character and temperament of the celebrity” after whom the sandwich was named. The custom began, he said, when a showgirl named Annette Seelos, who had just been hired for a small part in a Charlie Chaplin film being filmed in New York, came into his “shtoonky delicatessen store” on Broadway and Seventy-Third Street and asked him for a free sandwich; he obliged by putting Virginia ham, roast turkey, Swiss cheese, and coleslaw on rye bread. But although she wanted to have the sandwich named after her, he decided to name it after himself.26

It was Reuben’s exuberant, enticing ambience that made it into a key place for Jews to show off their rising economic and social position in America. An ad for Reuben’s in a program of the Ziegfeld Follies from the early 1930s urges theater patrons to dine at the restaurant after the show, since “no evening’s entertainment is complete without a visit to Reuben’s—where delectable food is served in charming atmosphere—where persons who have ‘arrived’ foregather to meet their friends.” The ad suggests that the restaurant is extremely high class and caters to an affluent customer base; it contains silhouettes of upper-class men in top hats and wealthy women in fashionable mink coats.27

This was the mirror that the delicatessen reflected to its largely lower-middle-class Jewish customers; it showed them not as they were but as they desperately, urgently desired to be. The window of the nonkosher delicatessen store provided a glimpse into an intensely Jewish space, but one that held the promise of magical, almost mystical, transformation. It reassured Jews that they had begun to “make it” in America.

Using the slogan “where a sandwich grew into an institution” (later replaced, by the early 1930s, by the even more exalted “from a sandwich to a national institution”), Reuben’s thus walked a thin line between proclaiming the overt Jewishness of its milieu and projecting an enticing image of acculturation. By claiming that it had become “institutionalized” in American life, the delicatessen implicitly suggested that Jews themselves were beginning to join the framework of American society, to become part of the very structure of American life by downplaying their religion in favor of a more secular way of being Jewish.

Perhaps the most showbiz-style delicatessen of them all was Lindy’s, which was opened on August 20, 1921, by the German immigrant Leo Lindemann and his wife, Clara, who had met when he worked as a busboy in her father’s restaurant, the Palace Cafe at Broadway and Forty-Seventh Street. Lindemann and his wife attended the opening night of Broadway shows, and the stars reciprocated by patronizing his restaurant. By the end of the decade, the enterprising deli owner opened a second location across the street and two blocks uptown. (By the late 1930s, he expanded the second restaurant to serve 344 people, with tables turning over ten times a day.) The delicatessen also captured a lot of business during the dinner break between the two parts of Eugene O’Neill’s Strange Interlude at the nearby John Golden Theatre. Lindy’s was famous for making sandwiches with entire loaves of rye bread sliced lengthwise and for serving huge slices of strawberry-topped cheesecake.

Lindy’s was immortalized in a series of interwar short stories by the journalist Damon Runyon, later adapted into the 1950 Broadway musical Guys and Dolls, in which a delicatessen called Mindy’s was the gathering spot for a collection of colorful gangsters. Runyon’s genius was to realize that the theater-district delicatessens were places where lower-middle-class Jewish men went to feel more successful, masculine, and American. (Runyon rarely strayed from this milieu in his work, once noting, “As I see it, there are two kinds of people in this world; people who love delis, and people you shouldn’t associate with.”)28 Take, for example, the opening of “Butch Minds the Baby,” about a gangster’s comical struggles in looking after an infant: “One evening along about seven o’clock, I am sitting in Mindy’s restaurant putting on the gefilte fish.”29

Putting on the gefilte fish? Where, in heaven’s name, was he putting it? Actually, the expression “putting on the gefilte fish” is a play on the expression “puttin’ on the ritz,” meaning to assume upper-class airs. Irving Berlin’s famous song “Puttin’ on the Ritz” asks, “Have you seen the well-to-do / Up and down Park Avenue / On that famous thoroughfare / With their noses in the air.”30 But it is also a play on an earlier expression, “puttin’ on the dog,” which refers to the practice of cradling a poodle or other small dog on one’s lap as an emblem of a luxurious lifestyle free from physical exertion; many prosperous Victorian women, including Queen Victoria herself, had their portraits done with dogs on their laps. The expression was current in America during the Victorian period; Lyman Bagg, who graduated from Yale in 1869, used the expression in describing how students showed off at his alma mater: “To put on the dog, is to make a flashy display, to cut a swell.”31 The elevation of gefilte fish helped Jews to enter the American mainstream, to swim with the changing tides of American social and economic life.

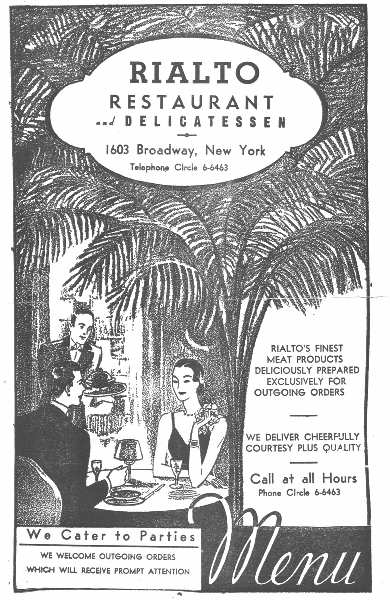

In line with the desire of Jews to become more American, delicatessens often promoted an image of upscale dining that was quite incongruous with their actual fare. The cover of a blue-and-white 1945 menu from the Rialto Restaurant and Delicatessen displays a pen-and-ink drawing of an elegantly dressed couple being served by a tuxedo-clad waiter holding a covered chafing dish; the man and woman sit under an immense fern as they drink their cocktails and gaze at each other in the light of a small, shade-covered lamp on their table. However, the Rialto’s offerings were considerably less lofty than such an image of fine dining might suggest; the menu items ranged from tongue and cheese sandwiches to pastrami omelets. It seems unlikely that any of this food was served from chafing dishes! The exterior of the menu represented how Jews wanted to be seen on the outside; the interior revealed how they actually felt and operated on the inside, still tied tightly to their ethnic origins.

This contradictory self-image may have led, in some ways, to the growth of Jewish popular culture. The burgeoning Jewish audience, as well as the many Jewish members of the entertainment industry, led to an increasing number of plays and films that centered on New York Jewish life and that showed the travails—both external and internal—that Jews faced in becoming American.32 Because it was almost de rigueur for comedy sketches and scenes that centered on Jewish life to take place in delicatessens, the Jewish eating establishment often became the place for the working out of these conflicts.

For example, Kosher Kitty Kelly, a 1925 Broadway musical that was turned into a silent film in 1926, showed the Jewish eatery as a place for different ethnic groups to come together. The Yiddish-accented deli owner Moses Ginsburg is friendly but disreputable; he secretly peddles alcohol in milk bottles. Ginsburg’s “stricktly” kosher delicatessen store has a diverse customer base that includes African Americans, Greeks, a Swede (who turns out, unluckily for Ginsburg, to be a Prohibition agent), and a Chinese laundryman. Ginsburg also tries to serve the Jewish community by playing matchmaker; he attempts to get a Jewish girl named Rosie Feinbaum to give up her Irish beau, Pat O’Reilly, for a Jewish doctor named Morris Rosen. Unfortunately, Morris already has a girlfriend, Kitty Kelly, the Irish girl of the title.

Despite the characters’ camaraderie, almost all of them are so intensely xenophobic that they believe that foreigners should be either kept out of the country or killed. Rosie fantasizes about marrying Pat in order to “get into a different atmosphere, away from [her] own people,” where she could bleach her hair blond and stop being identifiably Jewish. Morris’s mother, Sarah, goes to a meeting to find out how New York can be purged of “foreigners”—when she gets there, she is shocked to learn that they want to get rid of all immigrants, including the Jews! Meanwhile, the Chinese laundryman, Lee, whom the other characters call “the Chink,” attends a gathering of the tongs, the Chinese gangs that aim to “kill all foreign devils” and take over the drug trade in the city. Everyone seems to get along fine only as long as they’re all buying food—and drink—in the delicatessen, the all-purpose symbol of racial and ethnic harmony.33

Jews and Irish also encounter one another in the 1926 silent film comedy Private Izzy Murphy, which marked the debut of the director Lloyd Bacon. George Jessel plays an enterprising Jewish delicatessen owner who opens two stores, one in a Jewish neighborhood and one in an Irish section. In order to impress his Irish girlfriend, Eileen, with his bravado, Goldberg enlists in the army disguised as an Irishman. When his all-Irish regiment wins a big battle, the Jewish doughboy shares in the victory. The word “private” in the title is a pun; Izzy hides his true identity until he can demolish the stereotype that attaches to it, the stereotype of the Jew who is accomplished in business but not on the battlefield.34 Both films, like the long-running film series The Cohens and the Kellys and the film Clancy’s Kosher Wedding, capitalized on the popularity of Anne Nichols’s Abie’s Irish Rose, a record-breaking Broadway play that combined the ethnic humor of stereotypical Jewish and Irish characters.35

But Jewish delicatessen food did not automatically help to build bridges to non-Jews. In an early short talkie, The Delicatessen Kid, produced in 1929, the comic Benny Rubin plays the starstruck son of a delicatessen owner (Otto Lederer) who imitates the different singing and dancing styles of the various (non-Jewish) entertainers who patronize the store, who are modeled on such luminaries as Eddie Leonard, Bill “Bojangles” Robinson, and Pat Rooney. Much of the humor comes from the fact that these non-Jewish customers do not seem as appreciative of Jewish food as the father would like; one refuses to buy pickles along with his sandwiches, while another—the Bojangles character—asks in vain for pork chops.36

The Jewish Delicatessen Waiter

Even as delicatessens became both setting and theme for popular culture, they took on a highly theatrical vibe of their own. Beyond the celebrity atmosphere, one of the most entertaining aspects of the Jewish delicatessen was provided by the stereotypically snooty Jewish waiters, many of whom were former actors from the Yiddish or vaudeville stage. Jewish delicatessen waiters were frequently bossy and obnoxious to the customers; they told them where to sit, what to order, and how to behave. They acted, in other words, more like the famously snooty waiters in high-class Parisian restaurants than the servers that one would expect in a New York sandwich shop.

The short-tempered, sarcastic delicatessen waiter was always ready with a cynical remark that cut the customer down to size like an expert tailor taking a swipe at a garment. He expressed the resentment, always bubbling above the surface like the froth on a glass of seltzer, that the Jewish laborer felt for those who were starting to put on airs. The waiter was also left behind in a backbreaking occupation, serving his social betters with food that symbolized upward mobility.37 As Diane Kassner, the bewigged and heavily-made-up waitress who worked for decades at the Second Avenue Deli, intoned with a mixture of stoicism and regret as she dumped matzoh ball soup from a tin cup into a customer’s bowl, “You’ll be the richer; I’ll be the pourer.”38

Many waiters labored for decades in the same restaurant; it was not uncommon for the waiters at Ratner’s (which was a well-known dairy restaurant) to work into their eighties or nineties. It is no wonder that the waiters at Lindy’s joked about writing a book about their experience, under the title “I’ve Waited Long Enough.”39 The Jewish waiter was, in Alan Richman’s words, “as much as an American original as the workingmen who drove herds of cattle, laid railroad tracks, built skyscrapers.” The only difference, he conceded, was that the waiter “just moved a lot slower.”40

Why did customers want to be insulted or treated jocularly when they ate in Jewish delicatessens? Most Jews were probably able to discriminate between what was truly nasty or inattentive treatment and what was essentially an appeal to a common “language” or way of interacting, in which raised voices and sarcasm were a shared inheritance from Yiddish immigrant culture. Who else could talk to you so obnoxiously other than a close friend or family member? “A waiter in Lindy’s,” it was said, “is not only your servant. He’s also your relative.”41 The waiter was a kind of surrogate uncle or grandfather for the duration of the meal; he paradoxically made you feel at home by treating you with undisguised contempt.

Furthermore, the hostile-seeming server was nothing new in American culture. An anonymous New York waitress, quoted in 1916, was asked about the effect of the work on her physical and emotional state. “Sore feet and a devilish mean disposition,” she responded.42 In the early years of the twentieth century, when women were first being hired in significant numbers as waitresses (until then, the idea of having women serve male customers carried awkward sexual connotations), the stereotype of the ill-mannered “hasher” developed. “Almost everyone agreed that the ‘hasher’ (girl who waited table) of a generation ago was an untidy, uneven-tempered, unpredictable creature,” noted one observer during the Depression. “She didn’t have charm.” But by the 1930s, an important change had occurred, in that “pulchritude and personality are just as necessary to the food-dispenser as pork chops and pastrami.”43

Many non-Jews also enjoyed being ribbed by the waiters, despite the disparity between the way in which they were treated in non-Jewish restaurants and the delicatessen waiters’ brusqueness. The sociologist Harry G. Levine recalled that his Irish and Scotch-Irish mother, who hailed from Hibbing, Minnesota, after she saw a Broadway show made a beeline for the Stage or Lindy’s, where she could look forward to an equally diverting performance from a different breed of entertainers, the “bossy, know-it-all waiters,” whom Levine said were no less salient in his memory than “the Formica tables, the walls lined with pictures of celebrities [he’d] never heard of, the glass cases filled with enormous cheesecakes, and the multimeat sandwiches named after comedians.”44

The Jazzy “Delicatessen Wife”

Outside the theater district, the appeal of the delicatessen spread rapidly, as take-out food suddenly jumped in popularity. While the immigrant Jewish wife was expected to cook for her family, the second-generation Jewish wife began to pay others to cook for her and her family. A Yiddish song recorded in the late 1920s by Pesach Burstein, “Git Mir Di Meidlach Fun Amol” (Give Me the Girls from Yesteryear), lamented that modern Jewish women danced to jazz music, smoked cigarettes, and fed their men with gassy food from the corner delicatessen. If only, the singer fantasized, he could find one of the virtuous old-time girls—non-Jewish girls, it seems—with blond hair, beautiful braids, and the inclination to prepare home-cooked meals for her beau.45

Even after marriage, it seemed, Jewish women continued to take food out from the local delicatessen. As the homemaker Ethel Somers complained in 1927, “In this age of delicatessen lure, simple home dinners are becoming all too uncommon. . . . They are commonly shunned.”46 Sometimes it fell to the husbands to do the delicatessen shopping, perhaps because their wives were out of the house. “Already some of the young men who married last June are dropping in at the delicatessen about dinner time to get a few sandwiches,” a humor column in Life magazine noted sarcastically in 1929.47

At a time of expanding freedoms for women, many conservative commentators viewed delis as enabling women to evade their household responsibilities. What would women do if they no longer had to spend the afternoon shopping and cooking for dinner? Either they could keep working after marriage, or they could use their afternoons for leisure pursuits such as playing cards, going to film and theater matinees, clothes shopping, reading novels, and attending meetings and classes. As a Brooklyn Jewish mother in Daniel Fuchs’s proletarian novel Homage to Blenholt noted sarcastically, “all the young ladies, they don’t cook like the older generation. Lunch they eat in the delicatessen stores with the baby carriages outside, and in the night when the husbands come home from work, they throw together pastrami, cole slaw, potato salad, and finished, supper.”48

These New York housewives were, to some extent, following in the footsteps of the feminist and social reformer Jane Addams, who founded Hull House in Chicago, a settlement house with a heavily Jewish clientele. As early as 1904, Addams had advocated the ordering of all food from take-out stores in order to release women from “domestic servitude.” As Everybody’s Magazine reported, “She would have your meals delivered at the house-door, just as the returned washing is. Your beefsteak would be ‘done’ as your linen is. Cooking is drudgery and should be ‘done’ on the outside. . . . [She] [f]ound great bake, soup, meat, delicatessen shops.”49

Women could join the workforce and still, through taking out food, have dinner on the table when their husbands walked in the door. This, according to the journalist L. H. Robins, helped to create the “beehive” nature of the New York economy, which generated greater wealth than any other city on earth. But it was not just that the wives were earning money that made the husbands tolerant of all the take-out dinners they ate from the delicatessen. Robins insisted that most husbands would rather keep their wives from toil, thus preserving their beauty, than sit down to a home-cooked repast at the end of each day.50

The effect of delicatessen food on customers’ marriages was a matter of heated debate. One deli owner reported in 1925 that his interaction with his customers gave him intimate knowledge of what was going on in their homes; he boasted that he was a greater expert in marital relationships than were Brigham Young, King Solomon, and the local family court judge put together! The secret of a good marriage, he disclosed, was to live near a delicatessen, speculating that if the range were stolen from some of his customers’ kitchens, it would take a month before they would notice the theft.51

Others, by contrast, viewed the delicatessen as destroying marriages and disrupting family life. At an annual convention in Baltimore of the General Federation of Women’s Clubs, its president, Mrs. John D. Sherman, claimed that the “delicatessen wife,” a term that she evidently coined, gave her husband grounds for divorce. She linked the buying of prepared food to participation in other “jazzy” activities, coupled with an alarming tendency to shirk the housework.52 As Agnes V. Mahoney of the Industrial Survey and Research Bureau put it, it was precisely the reliance of many wives on the corner delicatessen and its “ready-cooked tin-can food” that had increased the incidence of broken homes.53

Florence Guy Seabury’s satirical essay “The Delicatessen Husband” took up the situation of a man who “lives from can to mouth.”54 Since his wife works long hours as a chemist, he is delegated to do the household shopping. But he feels emasculated by the shopping experience, viewing delicatessens in particular as home wreckers and “emblems of a declining civilization.” In short, he concludes, they are “generations removed from his ideals.”55 Nevertheless, by the turn of the twenty-first century, Seabury predicted, everything from clothing to newborn babies would arrive wrapped up in neat delicatessen-type packages. Seabury suggested that the proliferation of delicatessens represented a degree of progress since while a delicatessen husband might be “cursed with the task of bringing into his walled apartment his share of the canned tongue and chicken wings,” he at least did not have to slaughter the animal himself or split the wood to make the fire for his own dinner and coffee.56

Delicatessen stores were also viewed as the unfortunate byproducts of powerful new technologies that were rapidly reshaping American culture. One prominent critic, Silas Bent, assailed the toll on the mind and body that the “mechanized” way of living was beginning to take. Bent viewed the speed with which food could be produced and circulated as symbolic of the drastic changes in modern life. In a chapter titled “From Barbecue to Delicatessen Dinner,” Bent traced these developments from primitive man’s way of eating to the modern methods by which foodstuffs were circulated around the globe. The almost instant availability of an astonishing variety of food, Bent believed, caused a host of both physical and emotional problems. “The machine,” Bent lamented, “is sending more and more of us out of the home into restaurants, cafeterias, clubs and hotels; it is making us soft and dyspeptic, hurried and worried.”57

Those men who brought delicatessen food home without first requesting permission of the lady of the house risked becoming the target of considerable wrath. In Arthur Kober’s short story “You Can’t Beat Friedkin’s Meats,” published in 1938 in the New Yorker, Mrs. Gross is enraged when her husband brings home a large paper bag of cold cuts from the local kosher delicatessen for their Saturday lunch. “Mine cooking is no good, ha?” she explodes, before rushing out to throw the food in the face of the hapless delicatessen owner.58 Similarly, in Jo Sinclair’s major work of postwar fiction, Wasteland, a Jewish mother is horribly insulted when her grownup son purchases corned-beef sandwiches for his Friday-night repast rather than eat her cooking.59

Yet, by the interwar era, the delicatessen had become the quintessential urban store, preserving denizens from having to cook for themselves whenever they found it impractical or inconvenient to do so. By 1921, according to an advertising-industry trade publication, there were already 319 delicatessens in the Bronx, even though Jewish migration to the neighborhood had not yet reached its peak.60 The humorist Montague Glass jokingly suggested that a “booster” sign be erected at the entrance to the city reading, “New York: Gateway to Westchester County,” with the “information” that “New York City Contains 9,622,849 Delicatessen Stores (Estimated) and Over 38,658,031 Miles of Electric Railroad.”61

Nor was the popularity of delicatessens limited to New York. As one journalist in Baltimore put it, a “studio apartment, with a cocktail shaker and a dinner furnished by the nearest delicatessen store, usually represents the sum total of standardized living among thousands of city dwellers in these modern times.”62 Tracing the history of the delicatessen store from its modest beginnings as a purveyor of “Swiss cheese and pickled lambs’ tongues” to its gussied-up modern incarnation with its menu of “broiled guinea hen and mushrooms under glass to alligator pear salad and petit fours,” she found that the delicatessen had come a long way in the sophistication of its fare and the elegance of its window displays. Indeed, she noted, delicatessen stores in America were judged superior to their European counterparts, given the greater variety of foods available in this country—“tomatoes, peaches, alligator pears and pineapples are rare and expensive luxuries abroad, while they are plentiful and comparatively cheap here.”63

Just as before the First World War, Sunday night remained the delicatessen’s busiest time of the week. Calling the delicatessen the “urbanite’s pantry-keeper,” Robins dubbed those delicatessens that were open on Sundays “oases in a desert of locked-up plenty.” The delicatessen was, he noted, nothing short of a “life saver” for those who were entertaining unexpected guests, for families whose cook had walked out, for travelers who came back from vacation to an empty larder, for people who decided on the spur of the moment to have a picnic, for those who had planned to go the beach but whose plans were foiled by rain—actually “for almost any kind of New Yorker there is.”64

Heyday of the Kosher Delicatessen

Meat was a mainstay of the Jewish diet throughout the Depression. According to Louisa Gertner, writing in the Yiddish Daily Forward in 1937, even in the summertime New Yorkers ate “more meat than [the population of] entire nations.”65 Much of this meat was sold in delicatessens. In S. J. Wilson’s 1964 novel Hurray for Me, set in the early 1930s, a Jewish mother confesses to her family that she has not had time to make dinner. One of her sons suggests delicatessen “for a change.” The mother scoffs at the suggestion, noting sarcastically that he eats deli every day for lunch. The son asks how she knows. Her tart reply: “Because I ate deli five times a week when I went to high school . . . and your father did, and so did everyone else. What else is there to eat when you go to school?”66

The number of kosher delicatessens alone was staggering. According to a list compiled in 1931 by Thomas Dwyer, commissioner of public markets, there were 1,550 kosher delicatessens in New York City, in addition to 6,500 kosher butchers, 1,000 kosher slaughterhouses for poultry, 575 kosher meat restaurants, and 150 dairy restaurants. All in all, he stated, there were more than 10,000 kosher food dealers in the city.67 Two years later, Koenigsberg used the list as the basis for a plan submitted to Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia for the hiring of seventy inspectors to enforce the kosher laws.

Furthermore, according to a study conducted by Samuel Popkin for the Mogen Dovid Delicatessen Magazine, there were more than twenty-three hundred delicatessens—both Jewish and non-Jewish—in New York in the 1930s, representing almost a quarter of all those in the United States at the time.68 Popkin found that the total volume of sales in the delicatessen industry had reached $40 million. But he asserted that only the last eight months of each year were profitable for the delicatessen business, at least in the Northeast, since in these seasons there is a tendency for people to eat outdoors; “many people go to nearby parks and beaches and in all cases the most convenient and relatively appetizing lunch is delicatessen.” Indeed, the best season for delicatessen food is summer, when “jaded appetites demand some spicy food,” pointing them straightaway to the local delicatessen.69

In upscale neighborhoods, such as the Upper West Side (where, by the mid-1920s, more than half of the Jewish heads of household were garment manufacturers), ethnic Jewish businesses of all types helped prosperous Jews to resist lingering feelings of vulnerability in American society and to maintain a powerful sense of ethnic solidarity. As David Ward and Oliver Zunz have noted of second-generation Jews, “The physical attributes of the upper-class neighborhood they fashioned catered to their sense of urbanity and style, while its ethnicity, visible in the solid synagogues, kosher butcher shops, bookstores, delicatessens and bakeries, nourished a sense of cohesion despite their minority status.”70 The Jewish labor leader David Dubinsky had only to be glimpsed on one of his frequent jaunts to a kosher delicatessen in order to seem genuinely like one of the union rank-and-file.71

Jewish delicatessens, Daniel Rogov has noted, tended to be located in older buildings and to have worn furnishings, tarnished silver, chipped plates, an antique cash register (and an even more antique person sitting behind it), and an overall down-at-the-heels atmosphere. As he put it, “Some maintain the mood, if not the actuality, of sawdust on the floors and nearly all feature large plate glass windows with no trace of draperies.”72 In Brooklyn, many of the delicatessens were constructed by Murray Hager, who was a well-known builder. The salamis hung in an arc in the window, the neon signs flashed the name of the deli and the company that supplied the meat (e.g., Hebrew National, Zion Kosher, 999), and there were towers of canned beans. They had light oak chairs with pink vinyl seats, wood-grain Formica on the tables, and a decoration over the entrance to the kitchen that typically featured plastic flowers overflowing from a plastic flower pot. As the restaurant designer Pat Kuleto recalled in 1990, “Until recently, there was no such thing as deli design. They were always started on a budget, so you’d simply buy the cheapest restaurant equipment. Then you’d put a few sandwich signs up on the wall, a few pictures of the owner, a couple of notices from the government and a few posters supplied maybe by the RC Cola Company or something. You’d turn the lights up real bright, hang a bunch of sausages around. . . . And that was it—they called it a deli.”73

The main feature was, of course, the delicatessen counter, with the row of meats on display and hand-lettered signs on the walls advertising the prices. As the historian Ruth Glazer pointed out in the 1940s, delicatessens would “hide demurely behind window displays of dummy beer cans. But for those who have eyes to see there are steaming frankfurters and knishes on the grill and untold delights behind the clouded glass and shredded colored cellophane.”74 Some delicatessens were larger and more elaborately decorated than others. The larger, more famous kosher delicatessens—Grabstein’s, George and Sid’s, and the Hy Tulip—were in Brooklyn, with smaller, storefront-type delicatessens more typical of the Bronx.

Paradoxically, the number of kosher delicatessens grew even as fewer Jews kept kosher. An especially large decline of kosher observance, that of close to 30 percent, occurred between 1914 and 1924, as the second generation came to the fore. Ironically, this was at a time when almost half of the entire city’s meat supply was slaughtered according to the kosher regulations, as government reports from 1920 show.75 A survey done in 1937, after the publication of The Royal Table, the first popular guide in English to the Jewish dietary laws, found that the proportion of Jews keeping kosher had decreased even further than in preceding decades. It concluded that no more than 15 percent of the Jews in the United States kept strictly kosher, while 20 percent observed the kosher laws inconsistently and the other 65 percent—most of whom belonged to the Conservative or Reform branches of Judaism—scarcely bothered to keep kosher at all.76 As a review of the guide put it, the American Jew has “seen the tempo and flow of America’s modern industrial life break down the rigid barriers between Jews and Gentiles [and] kick his cumbersome dietary rituals into a cocked hat. To keep up the pace, it is easier to go Reformed with its worship of Judaism adapted to eight-cylinder cars, subways and cafeterias.”77

Nevertheless, the kosher delicatessen remained essential for those Jews who did continue to keep kosher, who still identified “kosher” with authentically Jewish, or who had more observant relatives with whom they dined on a regular basis. An investigator for a study of New York foodways by the Works Progress Administration concluded that the success of Rosenblum’s Delicatessen on Manhattan’s Upper West Side was based largely on its reputation as a place where religious laws were followed to the letter. He reported that the elder Rosenblum, who wore a skullcap and beard, ran the cash register but seemed present “more for decorative than business purposes, giving the place an air of religious orthodoxy.” This was important, given that his two sons did not appear to be religiously observant.78

However, while some delicatessens stopped selling kosher meat, others became kosher for the first time in the 1930s. Herb Rosenberg, whose father owned a deli in Brooklyn, recalled that as more Jews moved to Coney Island, the demand for kosher delicatessen products increased significantly. Not all the clientele kept kosher, and many were not Jewish. For example, the black actor Lou Gosset was a regular at the deli; his grandmother cleaned houses in the neighborhood to support her extended family. But in order to compete with the six other Jewish delicatessens on the twenty-three-block stretch of Mermaid Avenue where Herb’s father’s store was located, his father decided to make his store kosher. Pressure from religious authorities was also a factor; Herb remembers the local rabbi, who was preparing the boy for his bar mitzvah, trying to convince his father both to close on Saturdays (which they did not end up doing) and to sell only kosher meats.79

Some Jews strove mightily to convince their coreligionists to maintain the dietary laws. “Borrowing heavily from anthropology to zoology,” the historian Jenna Weissman Joselit has noted, “its defenders alternately sanitized, domesticated, aestheticized, commodified, and otherwise reinterpreted the practice of keeping kosher.”80 But they had little effect on the majority of their fellow Jews, for whom living in America largely meant eating what other Americans ate. Many Jews developed a workable compromise; they kept kosher at home but relaxed their standards when they ate out, thus making a distinction between their private and public lives. Indeed, Mordechai Kaplan, a Conservative rabbi who founded the Reconstructionist Movement, sanctioned the practice of keeping kosher at home but eating out in nonkosher restaurants as a way of balancing Jewish particularity with the need to live in the larger society.81

The kosher delicatessen thus symbolized ethnic community and continuity. According to Deborah Dash Moore, second-generation Jews “continued to endow the urban environment with ethnic attributes” such as food stores and restaurants.82 While she does not write about delicatessens in particular, Moore notes that “even middle-class neighborhoods would transmit a Jewish tinge to secular activities pursued within their boundaries.”83 It is little wonder that, according to the historian Elliot Willensky, garlic was the “common gastronomic denominator” for most of the ethnic cuisines of Brooklyn and was the basic ingredient in the food used in the kosher delicatessens, which advertised their presence all the way down the street. Even the sidewalks, he said, had a “translucence that could be attributed only to regular—if unintentional—saturation with well-rendered chicken fat.”84

Pulling Together through the Depression

Many who worked in the delicatessen industry characterize it as a mishpoche, using the Yiddish word for “family.” As one storekeeper, Isidore P. Salupsky, told his fellow delicatessen owners in 1932 in the pages of the Mogen Dovid Delicatessen Magazine, “With the present unemployment and bad times in general, some of our stores are hardly able to exist, many of the stores can hardly pay their bills; some of them are hardly making a living.” The owners needed to band together, Salupsky implored, rather than undercutting each other with their prices.85

Among the hard-and-fast rules given to delicatessen owners in the pages of the Mogen Dovid were to avoid “knocking” a competitor’s products, to maintain a neat appearance, to beware of becoming “too familiar” with the customer, to avoid displaying any “excitement,” to refrain from shouting at the clerk or sweeping the floor when customers were present, to open the store on time in the morning, and to make periodic changes in the window displays.86 It was essential, deli owners realized, to distinguish their products from ordinary groceries. Only if delicatessen meats could continue to be viewed as delicacies would the industry have a future, given the higher prices of prepared meats. An industry expert, writing in the pages of another trade publication, called Voice of the Delicatessen Industry, noted that these products were a “necessary luxury” for consumers and insisted that delicatessen “must not follow in the footsteps of groceries with their emphasis on volume and lower prices.” The loyal customer, he explained, “looks upon delicatessen as choice food, as special relishes, and does not mind if he has to pay a bit more.”87

Nevertheless, the work was backbreaking. Eighteen-hour days were routine, with unceasing physical labor. Herbert Krupp, who supplied kosher delicatessens in New Jersey, recalled having to reach into barrels of meat so cold that his hands almost froze, grabbing the fifteen- to twenty-pound slippery pieces of corned beef by a nub or flap of fat, called the deckle, and schlepping them into the store, where he flung them onto the scale to be weighed. (Owners were always suspicious that the meat had been “pumped,” or filled with water to increase the weight.) Delicatessen owners who cured their own meat had to rotate the huge pieces of meat through basement barrels filled with brine and spices. Only after several days of curing could the meat finally be cut into manageable sections, cooked, and prepared for slicing.

In the wake of Prohibition, one almost guaranteed money maker was alcohol, so many delicatessens started selling beer. The future delicatessen owner Phil Levenson recalls standing on a Coca-Cola box as a young teenager selling hot dogs and beers for a nickel apiece in his father’s deli in the Bronx. The hothouse (flower) workers in the Bronx Park neighborhood were so thirsty after work, he said, that he once sold two half barrels of beer from a four-foot bar in just a couple of hours.88

Delicatessen owners often enlisted their children to help in the store. The parents of Murray Lefkowitz, a powerful union organizer who represented deli employees, met because the older Lefkowitz mistook his future wife for her sister, whom he had recommended for a job in a meat-processing plant scrubbing dirt off beef tongues. Another job that was often given to children was to produce what was variously called a “poke,” “toot,” or “toodle,” a small piece of wax paper twisted into a cone, filled with mustard, and crimped on the bottom. As Ruth Glazer noted, “As soon as the youngsters of the family are old enough to hold two ‘toots’ of mustard in one hand and a ladle of mustard in the other, they are pressed into service.”89

Irving Goldfried’s father had sold shoes in Poland before coming to the United States before the First World War. A friend recommended the deli business because the food sold fast: “You order your merchandise before the weekend, and already on Monday you have your money.” So in 1932, he bought a sixty-seat delicatessen (including an apartment in the back of the store) on Saratoga and Livonia Avenues in Brooklyn for $5,000. The waiters were college students from the neighborhood who needed money for tuition; the family worked behind the counter while Irving’s wife did the cooking. A hot dog, an order of french fries, and a soda each cost a nickel, and customers drifted in on their way to the bus stop or public school nearby. The elder Goldfried did not drive, so he walked a mile to the factory to pick up ten or twelve briskets in a baby carriage. Irving learned to work long hours as well, peeling potatoes in the backyard while listening to swing-band music on the Victrola.90

Exterior of Gottlieb’s Delicatessen on Myrtle Avenue on the Brooklyn-Queens border in 1950s (Collection of Ted Merwin)

Grandparents, aunts, uncles, and cousins also got into the act. Marty Grabstein, whose parents owned the popular Grabstein’s Delicatessen in Brooklyn, told me that it was really his grandmother who ran the place. He recalled her as a tiny woman wielding a carving knife. She would bang on the table and shout, “Morris, it’s getting busy!” when she felt that her son wasn’t moving fast enough to seat the long lines of customers.91 It made sense to hire—or simply rely on—family members, since finding good employees was often a struggle. Levenson quipped that his chef was “whoever walked in the door and stayed sober for two weeks.” Family members were always assured of a free meal, known as putting the bill “on the cuff.”92

Fred Molod’s father sold his delicatessen on the Lower East Side and moved to the Bay Parkway section of Brooklyn, where he bought another delicatessen in partnership with his father-in-law, who had been a presser in a garment factory. Molod recalls that since they lived across the street from the store, his father did not even own a suit. “The only time that we closed early was at eight p.m. on Friday night,” noted Molod. “We broke the fast of Yom Kippur by going back to the store and reopening for business.”93

The Delicatessen as a “Secular Synagogue”

The critic Alfred Kazin, who grew up in the Brownsville section of Brooklyn, famously described going to a kosher deli as a quintessential secular Jewish ritual. As he memorably recalled,

But our greatest delight in all seasons was “delicatessen”—hot spiced corned beef, pastrami, rolled beef, hard salami, soft salami, chicken salami, bologna, frankfurter “specials,” and the thinner, wrinkled hot dogs always taken with mustard and relish and sauerkraut. . . . At Saturday twilight, as soon as the delicatessen store reopened after the Sabbath rest, we raced into it panting for the hot dogs sizzling on the gas plate just inside the window. The look of that blackened empty gas plate had driven us wild all through the wearisome Sabbath day. And now, as the electric sign blazed up again, lighting up the words JEWISH NATIONAL DELICATESSEN, it was as if we had entered into our rightful heritage.94

Before he had even taken a bite, the illumination of the sign closed a powerful emotional and spiritual circuit for Kazin, connecting him with his tradition. Where (and, we could add, with whom) Kazin ate affected him profoundly. There was also something almost sacred about the neon delicatessen sign itself. The mystical glowing letters, connected by the tubes carrying the phantasmically colored gas, held a kind of kabbalistic fascination for Kazin and his peers. Just as medieval rabbis called the letters of the Torah “black fire written on white fire,”95 the shining letters of the sign hung in the air with the dazzling radiance of supernal energy.

The delicatessen became the seat of many of Kazin’s deepest and most important memories. As the scholar Naomi Seidman has insightfully pointed out, Kazin’s innovative form of storytelling is “not a map of the neighborhood, although the streets and landmarks and borders are duly and precisely recorded, but rather a map of a consciousness. . . . We are, Kazin seems to say, not so much what we eat but where we first ate, and slept, and walked; geography, in other words, is destiny.”96

Nostalgia for the delicatessen became, in the decades after the Second World War, an essential feature of secular Jewish life for the second generation of American Jews, who grew up at a time when a third of the population of Brooklyn was Jewish and almost one-half of the overall Jewish population of New York lived in that borough. The delicatessen was where this secular Jewish identity, in large measure, took root; it was where the Jewish community came together and nurtured its relationship to Jewish heritage.

Like the lighted delicatessen sign, the illuminated movie screen also held great fascination for secular Jews in the outer boroughs. Going to a Saturday movie matinee, at a time when talking movies (“talkies”) were still a relative novelty, was a cherished ritual for many Jewish children; there was seldom any contest between spending the Sabbath in the synagogue and spending it in the cinema. As Kazin noted, comparing the two, “Right hand and left hand: two doorways to the East. But the first led to music I heard in the dark, to inwardness; the other to ambiguity. That poor worn synagogue could never in my affections compete with that movie house, whose very lounge looked and smelled to me like an Oriental temple. It had Persian rugs, and was marvelously half-lit at all hours of the day.”97 And just as one could scarcely attend a Broadway show without also eating in a deli, a trip to the cinema typically involved a delicatessen lunch.

Delicatessens were often located near the movie theaters; for example, the RKO Movie Theatre in Ridgewood, Queens (on the border of Bushwick, Brooklyn), was across the street from Gottlieb’s, a kosher delicatessen that stayed open late to serve the crowd streaming out of the cinema. Similarly, the Ambassador Theatre in Brooklyn was next door to Goldfried’s; when the movie operators were hungry, they lowered a bucket from four floors up, and sandwiches were sent up on a rope and pulley.

Another movie theater, called People’s Cinema (formerly, The Bluebird), was located diagonally across the street; a former patron of the People’s recalled that kids would come in on Saturday afternoons with salami sandwiches, bottles of Pepsi, and cake and watch cartoons, westerns, and the installments in the “Little Tough Guys” or “East Side Kids” series about lower-class children and their adventures in the New York slums.98 Barbara Solomon’s father, who owned a deli in Sheepshead Bay, got four free movie passes a week because her father advertised the local movie houses by putting posters in the window. (Her father also provided the sandwiches for her dates.)99

Louis Menashe, a Sephardic Jew who learned to love Ashkenazic cooking, spent Saturday afternoons with friends at a movie theater on Broadway in Williamsburg, and then the group repaired to Pastrami King on Roebling Avenue and South Second Street, a block from his home. The hand-sliced pastrami was smoked with cedar (not the usual hickory) and flavored with fresh garlic (rather than the typical garlic salt). As Menashe recalled, “Press, the harried waiter, would ignore us kids—our tips weren’t so good—but the long hungry wait was worth it.”100 Some customers sneaked deli sandwiches into the movie theater itself. While waiting on a long line to get into Gone with the Wind in 1939, a group of young people “got hungry”: “so we bought hot pastrami sandwiches and pickles to take inside. The entire movie house stank of deli. An usher came up and said you can’t do that, but what could we do? We ate it anyway.”101

On summer weekends, beachgoers would stop at a deli to buy sandwiches for their picnic baskets. Paul Goldberg worked in his father’s delicatessen in the Flatbush section of Brooklyn. He remembers that customers would come in carrying beach chairs and hampers. “We hoped that the food wouldn’t turn green before they ate it,” he admitted. When the beachgoing traffic dropped off, Goldberg’s father hired a teenager to take sandwich orders from women waiting for their hair to dry in the local beauty parlor.102

Sunday night, in particular, was “delicatessen night” for many secular Jewish families, when extended families gathered for dinner in a kosher deli—or took food home. On the white dining-room tablecloth in the Bronx apartment in which the author Kate Simon grew up, she recalled, “appeared the traditional Sunday night company meal: slices of salami and corned beef, a mound of rye bread, pickles sliced lengthwise, and the mild mustard the delicatessen dripped into slender paper cones from a huge bottle. . . . The drinks were celery tonic or cream soda, nectars we were allowed only on state occasions, in small glasses.”103

Nevertheless, the relationship that the kosher delicatessen had with Jewish religion was a complicated one, and one that bespoke the myriad ways in which American Jews attempted to balance their Jewish and American identities. Many of these establishments were open on the Sabbath and Jewish holidays, despite the prohibition in Jewish law against handling money or doing business on such occasions. This reflected a schizophrenic attitude toward religious observance, in which it became comfortable for Jews to observe the Sabbath selectively, picking and choosing the rules that they wished to follow.104 Delicatessens did the same; Poliakoff’s, an upscale kosher eatery that included deli sandwiches on its menu, and Lou G. Siegel’s, a landmark kosher deli in Manhattan’s theater district, transgressed Jewish law by opening for business on Friday nights but requested, by putting notices on their menus, that patrons refrain from smoking (also forbidden by religious law on the Sabbath).

The historian Jeffrey Gurock recalls that when he was growing up in the East Bronx, his parents, who belonged to an Orthodox synagogue, would take their sons to kosher delis whenever the family chose to eat out. “However,” Gurock notes, “unlike their more scrupulous synagogue friends, my folks gave no thought as to whether the delis that we more generally frequented were open on Saturday. Nor did they ever peek into the back room to see if there was a mashgiach [kosher supervisor] on the premises.” As long as the Hebrew phrase basar kasher (kosher meat) was displayed in the window along with the logo for Hebrew National, his family felt comfortable eating in the restaurant.105

For some Jews, eating in a delicatessen became almost a religion unto itself. The sociologist Harry Levine noted that his father, Sid, a self-described “gastronomic Jew” who grew up in a family of poor socialist Jews in Harlem, “worshiped only at delicatessens,” where his “most sacred objects” included stuffed cabbage, chopped liver, salami, frankfurter, tongue, corned beef, and hot pastrami. Levine heard his father call himself a “gastronomical” Jew so frequently that the boy thought that it was a denomination of Judaism.106 Susan Stamberg, a host of National Public Radio’s All Things Considered, remembered, “Growing up in Manhattan in the 1950s, I thought the whole world was Jewish,” particularly when her father took her and her siblings to the Lower East Side every weekend for knishes at Schmulka Bernstein’s or Yonah Schimmel’s. “We were ethnic Jews more than observant ones,” she concluded.107

For some Jews, perhaps even nonkosher delis were too religious for comfort. In Jay Cantor’s 2003 novel Great Neck, a Jewish survivor of the Holocaust, Richard Hartman, patronizes an empty German delicatessen named Kuck’s (in Great Neck), where he takes out a roast beef sandwich with mayonnaise every night. “I’m not a Jew of faith, he thought, on the way back to his room, as he imagined the suburban householders who crowded Squire’s Jewish delicatessen were, or rather my faith is culture, like (he liked to think) Freud’s faith, or Kafka’s or Proust’s or Walter Benjamin’s, all the old Talmudic fervor now focused on secular texts.”108

During the interwar era, then, the delicatessen consolidated its hold on Jewish life—and on the overall culture of New York, at a time when gender roles were in flux and take-out food was starting to become popular. The nonkosher delicatessens in the theater district, which had been spawned as a way for Jews to eat mostly traditional food but to free themselves from the stringency of the kosher dietary laws, used their showbiz atmosphere to flatter Jews’ sense of their growing importance in American society and to provide a secular avenue to Judaism. In the following decade, at a time when many small businesses were closing because of the ravages of the Great Depression, the outer-borough kosher delicatessens also continued to thrive and even to multiply. But even as the delicatessen became the Jewish hangout par excellence, it quickly lost its hold on Jewish life with the coming of another world war, which led to meat rationing and exposed Jews to other types of food, both at home and abroad. The delicatessen—and Jewish Life—would never be the same.