4

Miss Hebrew National Salami

The Movement to the Suburbs and the Decline of the Deli

In a classic Mad magazine cartoon from the 1960s, a family goes out to eat for the first time at an unbearably crowded, extremely chaotic Chinese restaurant. The meal is a nightmare: they can’t get a table, their uncle can’t decide what to order, the waiter ignores them, they stay so long that the table is removed, and then they tip the wrong amount. They are in a surrealistic environment, in which everything and everybody seems to conspire against them. Yet the very next Sunday night they find themselves once again standing in line at a chop suey joint. While the family is not explicitly marked as Jewish, the cartoon is filled with in-jokes for a Jewish readership; in the background, signs read, “Egg Foo Yong with Gefilte Fish” and “Chow Main Best! Liver Worst.”1 Jews were indeed developing a particularly intense relationship to Chinese food. The local Chinese restaurant became the neighborhood hangout on Sunday night, and going out for Chinese became a Jewish ritual in its own right.

Before long, it was the non-Jewish, ethnic restaurant rather than the delicatessen that served as a more popular gathering place for Jewish New Yorkers. But Jews still repaired to the delicatessen when they wanted to reconnect to their heritage. In the mid-1950s, the shortened form deli first came into widespread use. Joseph A. Weingarten noted in his 1954 dictionary of American slang that although he had never seen the word deli in print, it was common for people to say, “I’m having deli tonight” or “Mom, let’s have deli.” (He speculated that perhaps the word should be spelled “dely” or “delly” instead.)2

Beyond the attraction of Jewish New Yorkers to other ethnic cuisines, especially Chinese food, there were a host of other factors that led to the decline of the deli. While half of America’s Jews still lived in New York City, rising crime rates along with the rapid construction of new highways and middle-income housing developments impelled many to move to the suburbs of western Long Island, southern Westchester, southeastern Connecticut, and northern New Jersey.3 The Jewish movement to the suburbs, in which Jews were often in the minority, obviated the deli’s role as a neighborhood gathering place. As Jews desired to be viewed on an equal footing with other Americans, they downplayed their ethnicity and culture in favor of Jewish religion. Indeed, Jews began to define their identity in opposition to the foods that had sustained their parents in Brooklyn and the Bronx and to develop a more sophisticated, more multicultural, and more gourmet palate.

When the Brooklyn Dodgers, a team especially beloved by ethnic minorities because of its perennial “underdog” status to the New York Yankees, abruptly decamped to Los Angeles, Jews were among those who felt the most betrayed. As the sportscaster Howard Cosell put it, on a trip back to his old neighborhood in Brooklyn, it was a particular shock to see that Radin’s Delicatessen, located for decades near Ebbets Field (where the Dodgers had played) had closed. Radin’s was, he recalled ruefully, “the ‘Stage Delicatessen’ of Brooklyn, the eatery for ballplayers. Hot dogs (crisp, all-beef ones) were always ready on the grill. The hot pastrami was unfailingly lean. You never had to ask, the tongue would be cut from the center. . . . Franklin Avenue without Radin’s had to be like a man without a country.”4

In 1960, there were still more than five dozen kosher delis in Brooklyn, with names like Schneier’s or Schnipper’s5—the kinds of names that the deli owners’ sons had already changed when they graduated law or business school. But rising crime rates often made running a deli untenable.6 In a particularly disturbing incident, a partly crippled deli owner on the Lower East Side killed two would-be teenage robbers with a carving knife when they invaded his cash register.7 Paul Goldberg’s father showed more restraint; when he caught someone trying to reach over the counter to grab a salami, he simply whacked him on the hand with the flat side of a knife. A Jewish lawyer recalled that it was the robbery of a deli in his neighborhood in East New York that was the last straw; his family no longer felt safe in the city.8

Some delis followed Jews to the suburbs; for example, when the Glen Oaks shopping center in eastern Queens was completed in 1950, Grodsky’s Delicatessen could be found sandwiched among May’s Department Store, F. W. Woolworth’s, Dan’s Supreme Super Market, and a slew of smaller stores.9 Nevertheless, the historian Edward Shapiro has noted that in a typical postwar suburb, the local stores did not sell Jewish newspapers, there were no kosher butchers, synagogues were few and far between, and, last but not least, “corned beef sandwiches were not readily available.”10 The few delis that sprang up in suburban shopping malls still served as gathering places for segments of the Jewish population, but the community itself was weakened by dispersion and by the diminution of close ethnic ties. While Jews still sought to maintain a distinct ethnic identity, they did so in the context of a society that valued sameness and unity.

Other delis closed because the owners did not want their children to have to work the long hours that running a restaurant entailed. As the historian Karen Brodkin Sacks has noted, Jews “became white” by taking advantage of the G.I. Bill and federal home-loan guarantees—these programs enabled returning servicemen to go to college and to buy a house. This helped Jews to move squarely into the middle class and become professionals. Given their greater economic opportunities in American society, many children of deli owners viewed the prospect of taking over the family deli with distaste, if not outright disgust. In the Yiddish-English song “Sixteen Tons,” based on Tennessee Ernie Ford’s coal miner’s lament of the same title, the comedian Mickey Katz changed the shoveling of coal to the piling up of deli meats: “You load sixteen tons of hot salami / Corned beef, rolled beef, and hot pastrami.” He contracts a hernia from the physical strain of shlepping these meats, along with cake, beef intestines, and bagels.11

Interior of Zarkower’s Kosher Delicatessen in White Plains, New York, in 1962 (Collection of Ted Merwin)

The choreographer Jerome Robbins, whose father owned a kosher delicatessen on the same block as their apartment on East Ninety-Seventh Street, had no interest in going into the family business. As his biographer, Greg Lawrence, put it, “by the time Jerome was born, the inherited dream of success had magnified beyond anything that his lower middle-class father might have imagined.” Along with so many fellow Jews, he “would embrace the idea of putting as much social distance as possible between himself and his origins.”12

Susan Thaler, whose father owned Schlachter’s Kosher Delicatessen on 176th Street and Walton Avenue in the Bronx, was mortified by her father’s line of work. “Why couldn’t he take weekends off instead of a school day so we could do things together like a family?” she asked plaintively in an essay in the New York Times. “Why couldn’t he learn to speak English without an accent? Why couldn’t he sell the store and get a real job in an office where he could wear a suit and tie and carry a briefcase? Why couldn’t he be witty and tall and dapper like Mr. Anderson on ‘Father Knows Best’?” Only later in life, when she had a child of her own, did she belatedly conclude that her father was “blessed” rather than cursed by his humble occupation.13

Other daughters of deli owners bedecked themselves in expensive clothes and jewelry in an attempt to conceal their humble origins, of which they had a lifelong sense of shame. As the humorist Harry Gersh conceded, they were simply absorbing the sensibility of their time; it was demeaning to admit that your father worked behind the counter of a store. “A delicatessen store man is different from a candy store man or a merchant, but not much,” Gersh pointed out. “A little of the spice of the pastrami, a little of the fat he didn’t trim off the corned beef enters his soul.”14 Deli owners were stereotyped as low class; on the jacket of Jackie Mason’s 1962 debut album, I’m the Greatest Comedian in the World, Only Nobody Knows it Yet!, the comedian’s heavy Yiddish accent is described as “midway between that of a Bronx taxi driver and a Lower East Side delicatessen proprietor.”15

The Supermarket Delicatessen Counter

With the rise of atomic power and the coming of other scientific breakthroughs during the postwar era, frozen food was widely viewed as more modern and exciting than fresh food. Technology seemed to promise a future in which every food was appetizing, nutritious, and safe to eat. According to the historian Rachel Bowlby, every product was seen to be merely “awaiting its ideal package, to beautify it and to guarantee its cleanliness.”16 Many Jews “enjoyed kosher frankfurters, bagels, or a good piece of herring,” the historian Alan Kraut notes, “but they preferred their consumables spotless and packaged for easy storage.”17 Using technology such as vacuum-packing and freeze-drying—originally developed in order to send food to the troops overseas—frozen food was placed in a waterproof plastic or foil pouch, known as a “hotback,” that could be dropped in boiling water to reheat. “With our quarter-pound hotbacks of corned beef or pastrami that go into boiling water, you can have a hot pastrami on rye in a remote areas of Kansas,” Jack Chase, a sales manager for Hebrew National, boasted to the New York Times.18 When the sales staff of Zion Kosher went to call on supermarkets, they were armed with a laminated green card that showed photographs of their packaged products—everything from kosher frankfurters to liverwurst, kishka (stuffed derma), salami, and bologna.19

Ironically, these modern technologies were modern analogues of the smoking, salting, drying, and spicing that ancient peoples had used to preserve meat, fish, vegetables, and other foods.20 By freezing pastrami (which is already twice preserved, given that it is made from brisket that is cured and then smoked), Hebrew National was preserving it yet again, but for modern mass consumption. By 1947, the company was selling cans of stuffed cabbage, meatballs in gravy, spaghetti sauce and meatballs, rice with braised beef, corned beef hash, and potato pancakes. These products, all of which cost less than a dollar a pound, could be found at more than three hundred stores in the New York area.21

The packaging of Jewish food was, however, nothing new. Since the turn of the twentieth century, matzoh, gefilte fish, and other staples of Jewish holiday fare had been available in boxes, jars, and other containers. As the historian Jenna Weissman Joselit has found, Yiddish newspapers had advertised such products as Uneeda Biscuits, Quaker Oats, and Proctor and Gamble’s cooking fat Crisco (the availability of which, its makers proclaimed, represented the culmination of four thousand years of Jews waiting for a non-meat-based cooking fat that could be used for the frying of dairy products). In the 1920s, Joselit notes, “white bread, mayonnaise, and satiny-smooth Spry gradually assumed pride of place within the kosher kitchen, transforming it from an island of culinary superstition to a common meeting ground for tuna fish sandwiches and oatmeal cookies.”22 National consumer products were marketed to a Jewish population that prided itself, as the historian Andrew Heinze has found, on its ability to consume the same products as other Americans.23 The problem for delicatessens was that supermarkets sold many of the same items that they carried. By 1957, 83 percent of supermarkets sold cooked meats and potato salad, 67 percent sold coleslaw, and 61 percent sold baked beans. And almost two-thirds of these supermarkets prepared these items in the store itself rather than depending on any outside vendors.24

As a result, from 1929 to 1954, the number of delicatessens (of all types, not just Jewish ones) dropped nationwide by more than a quarter from around 11,000 to only 8,000. By contrast, the number of supermarkets, or “combination markets,” rose sharply from 115,000 to 188,000. By 1960, supermarkets sold 70 percent of the nation’s groceries.25 Waldbaum’s, founded by the Polish Jewish immigrant Ira Waldbaum, catered to a customer base of middle-class Jews. The business journalist Leonard Lewis compared Waldbaum to Moses; Waldbaum led Jews on their exodus from Brooklyn to the Long Island suburbs. By doing so, Lewis noted, Waldbaum’s became the “unofficial supplier to the children of this new promised land.”26

The historian Mark Zanger has noted that ethnic foods tend to become “softer and whiter” in the process of assimilating to mainstream American foodways.27 The flabby, bland, light-colored cold cuts sold in supermarket packages bore little resemblance to the chewy, spicy, dark-red slices of meat found in a traditional deli. While the average per capita consumption of meat in New York was more than three pounds a week in the 1950s, the trend was away from the type of meat traditionally served in a deli. According to Jerry Freirich, the owner of a kosher-meat-processing company, New Yorkers had become partial to lean meat that was not too spicy or salty, as compared to the South, where, he said, fattier, spicier, and saltier meats were still preferred.28

As the historian Marilyn Halter has noted, it was initially assumed by marketers that ethnic shoppers “would seek out local immigrant businesses involved in small-scale food production and retailing rather than consuming the products of corporate giants.”29 But for the most part, Americans of all stripes, including relatively new immigrants, eagerly embraced “ethnic” products sold by large food corporations. This made it difficult for mom-and-pop delis to compete. Sam Novick, a longtime salesman for a number of kosher meat companies, including Public National Kosher, City Kosher (founded by his father), and Hebrew National, put it bluntly: “The supermarket was part and parcel of the ruination of the neighborhood deli.”30

On the other hand, some supermarkets saw delis as a threat and sought to block them from renting space in a shopping center in which the supermarket was an anchor tenant. This attitude reflected long-standing tensions between small retail stores and supermarkets; the attorney Manny Halper recalled that as a child in the Bronx, he once heard his rabbi give a sermon exhorting housewives not to buy meat from the supermarkets but to patronize their local butchers instead. Halper started writing leases in New York in 1960, enabling retail stores, including scores of Jewish delis, to move from city streets to suburban shopping centers. But he insisted that he never prepared a lease for a supermarket on Long Island without including a clause permitting a Jewish deli in the same shopping center. “The deli never posed any kind of threat,” he said, “particularly a kosher deli, which sold different kinds of merchandise than the supermarket did.”31

Whether the precipitous decline in Jewish deli owners’ business could be attributed to the rise of the supermarket or not, it caused rage among them. In New York, their antagonism toward supermarkets allegedly grew so intense that they committed antitrust violations. If a kosher meat company agreed not to sell to local supermarkets such as Dilbert’s, Kubrick’s, Royal Farms, and Dan’s Supreme, then the Jewish delis in that neighborhood would purportedly band together and buy all their meat exclusively from that company. Companies that sought to sell to the supermarkets anyway, the government claimed, were threatened with violence. Fred Molod, a deli owner’s son who had become a lawyer for the Brooklyn branch of the Delicatessen Dealer’s Association, defended the delis. Molod brought a large map of Brooklyn into the courtroom, pushing colored pins into the map to mark the locations of the delis. He then put the deli owners on the stand to testify that there had been no unlawful cooperation. The government backed down from most of its allegations.

Here She Is . . . Miss Hebrew National Salami

With the decline of the deli and the mainstreaming of Jews into society, the kosher meat companies also realized that they needed a new marketing strategy. By such publicity stunts as sending salami-scented ads through the mails and anointing a “Miss Hebrew National Salami” and a “Miss Hebrew National Frankfurter” (the latter on the occasion of the company’s billionth hot dog sold), Hebrew National used sexual associations and offbeat humor to market its products beyond the Jewish community.

Sex in American advertising was, of course, nothing new; the historian Tom Reichert has found that it dates back to the 1850s, when drawings of nudes were first used to sell tobacco.32 But, with the advent of Playboy in 1953 and the many men’s magazines that followed in its wake, sexual images became more prominent and accepted in American culture. Sausages, because of their phallic shape, especially lent themselves to titillating advertising. While Jeanne Williams, a.k.a. “Miss Hebrew National Frankfurter of 1952,” simply cradled a long hot dog above her ample cleavage and was surrounded by pendulous hot dogs in the background, Zion’s “Queen of National Hot Dog Week of 1955,” Geene Courtney, wore frankfurters, sausages, and kielbasa as a crown on her head, as a belt around her waist, as a scarf-like chain thrown over her left shoulder, and as bracelets around her wrists, as if in some kind of sexual bondage.33 (As the activist Carol Adams has argued, meat has long been—and continues to be—advertised in our culture in ways that degrade women and that mirror pornography. According to Adams, “viewing other beings as consumable is a central aspect of our culture.”34)

Nevertheless, Hebrew National, in an ironic counterpoint to playing up the sexual undertones of its products, also emphasized the associations with purity, healthfulness, and cleanliness that many Americans associated with the word kosher. The company used the Good Housekeeping seal in its print advertising, along with a picture of a ribbon showing that the company had been commended by the consumer service bureau of Parents magazine. One ad campaign on New York City subways depicted a young boy balancing a Hebrew National salami on his head; the ad copy claimed that the food could be part of a healthy diet.35

Painted highway billboards, many located on commuter routes throughout the metropolitan area, focused on the company’s new use of a distinctive blue-and-yellow string to connect its sausages and frankfurters to one another. Ads on subways and buses, in addition to in delicatessens and supermarkets themselves, hawked the kosher meats. Newspaper ads ran not just in New York but in cities such as Providence, Pittsburgh, Hartford, Cleveland, and Washington, DC.

The company also sponsored 80 percent of the radio and television coverage of the 1953 and 1954 elections on the major radio networks—ABC, CBS, NBC, and WOR; it used the slogan “Make Election Night Party Night” to encourage listeners to organize gatherings and serve the company’s products. By promoting an association between Jewish food and voting, the company allied itself with ideals of patriotism and democracy. This fit with prevailing ideas about the role of consumption as a mark of good citizenship. According to the historian Lizabeth Cohen, “the new postwar era of mass consumption deemed that the good purchaser devoted to ‘more, newer, better’ was the good citizen,” that one “simultaneously fulfilled personal desire and civic obligation by consuming.”36

Hebrew National also produced as part of its marketing strategy a plethora of advertising items that reflected the ongoing acculturation process of the second and third generations of American Jews. These ranged from books of score sheets for gin rummy and canasta (popular card games that Jews played both at home and when they vacationed in the Catskills and in Miami Beach) to little, white, plastic trash bags with its logo and the slogan “Bag it and help keep our highways clean.” These give-aways implicitly recognized that Jews wanted to maintain their connection to their heritage and participate in the life of society on an equal basis with other Americans.37

Hebrew National was also a major sponsor of the many popular radio and late-night television programs on CBS hosted by Arthur Godfrey. Both Godfrey and the comic Steve Allen gave out free Hebrew National salamis to their studio audiences; free provisions were also distributed at telethons, benefit performances at Madison Square Garden, and other large-scale charity events. Meanwhile, parents were targeted through a campaign in which consumers were asked to send in examples of situations that their children tended to avoid (such as the dentist’s office, barber shop, music lessons, or bathtub) but for which a Hebrew National hot dog might serve as an effective bribe.38

In a radio spot on the most popular Jewish station in New York, WEVD (named for Eugene V. Debs, the socialist leader), a jaunty jingle by the Pincus Sisters announced that “for that old fashioned flavor that all the folks favor, try Hebrew National meats.” Customers who sought authentic Jewish food for their parties, late-night dinners, and other social occasions were urged to “be rational” and “serve meats made by Hebrew National.”39 One advertising campaign solicited sandwich “recipes” from Jewish New Yorkers who were then featured in its advertising along with their creations. Another campaign focused on the supposed favorite sandwiches of celebrities such as the actress Molly Picon and the comedian Morey Amsterdam. Not to be outdone, Zion Kosher sponsored a “name that cantor” contest on radio station WEVD; identifying a cantor from his singing alone would win prizes in delicatessen products.

The clever mass marketing of Jewish foods also embraced the rye bread used to make delicatessen sandwiches. Henry S. Levy & Sons was a kosher bakery on Thames Street in Brooklyn that had long supplied kosher delicatessens; in an ad in the early 1930s in the Mogen Dovid Delicatessen Magazine, it trumpeted its fifty years in the business contributing to “firm, even, tender sandwiches that look better and taste better” and advertised twenty-four-hour deliveries to all parts of the city.40 But by the 1960s, with sales falling precipitously, the company experimented with packaged rye, pumpernickel, and raisin breads in an effort to broaden its customer base, especially among non-Jews—a strategy that apparently alienated many of the bakery’s Orthodox customers. Howard Zieff at the Doyle Dane Bernbach advertising firm developed a series of ads featuring non-Jewish models, including an American Indian chief, an altar boy, a Japanese man, and an African American boy, eating deli sandwiches on rye with the tag line, written by Judy Protas, “You Don’t Have to Be Jewish to Love Levy’s Real Jewish Rye.”41 The African American activist Malcolm X liked the one with the African American boy so much that he had his own picture taken standing next to it.

Ordinary New Yorkers with their sandwich creations depicted in a 1950s Hebrew National promotional booklet (Collection of Ted Merwin)

As Zieff later wrote, “We wanted normal-looking people, not blond, perfectly proportioned models. I saw the [American] Indian on the street; he was an engineer for the New York Central. The Chinese guy worked in a restaurant near my Midtown Manhattan office. And the kid we found in Harlem. They all had great faces, interesting faces, expressive faces.” What he sought, he said, were “faces that gathered you up.”42 In the same way, Jewish food was starting to “gather up” a non-Jewish clientele, thus expanding the popularity of Jewish culture in America in ways that would only accelerate in the coming decades.

Jews Redefining Themselves as a Religious Group

From the 1956 release of Cecil B. DeMille’s The Ten Commandments to the rise of evangelical preachers such as Billy Graham, religion was resurgent in many Americans’ lives during the postwar era. The economic prosperity that fueled the rise of the suburbs, the growing focus on family life in the generation of the baby boomers, and the ascendancy of a militant anticommunism—all of these seemed to require legitimation in religious terms. At the same time, fear about the instability of life in an age of hydrogen bombs also led many Americans, including Jews, to seek comfort from religion. Best-selling books by religious leaders from Rabbi Joshua Liebman (Peace of Mind) to Norman Vincent Peale (The Power of Positive Thinking) capitalized on the need for reassurance that many Americans felt. Liebman’s book in particular, according to the historian Jonathan Sarna, “heralded Judaism’s emergence as an intellectual, cultural, and theological force within postwar American society.”43 But as Judaism took on a kind of high-mindedness and serious of purpose, Jews began to define themselves less as an ethnic group and more as a religious one, as a “faith” that was the equal of Protestantism and Catholicism.

One sees this shift in the Academy Award–winning 1947 film Gentleman’s Agreement, in which Gregory Peck plays a journalist who pretends to be Jewish in order to write a magazine article on anti-Semitism; he adopts none of the cultural or ethnic aspects of Judaism but simply announces that he is Jewish by religion.44 The rise of religion preempted Jewish ethnicity by substituting the social life of the synagogue for that of the delicatessen. True, as the sociologist Will Herberg noted, this newfound religiosity was often void of true meaning; it was a “religiousness without religion, a religiousness with almost any kind of content or none, a way of sociability or ‘belonging’ rather than a way of reorienting life to God.”45 But it sped the acculturation of Jews into American society by putting Judaism on an equal footing with other religious groups. This was summed up in the title of Herberg’s influential book Protestant–Catholic–Jew, in which he argued that Jews had become part of Christian America by emphasizing the religious rather than cultural aspects of their identity.

In order to find a specifically Jewish means of fitting into a society that placed a premium on morality and public religious behavior, Jews built palatial suburban synagogues as fortresses against assimilation. (Some people jokingly referred to this as an “edifice complex.”) While relatively few members—including, surveys showed, the congregational lay leaders—were interested in attending services more than a few times a year, the synagogue could generally muster a good turnout with a Saturday-night cultural program or Sunday-morning bagel brunch.

Even as Jews downplayed their ethnicity, then, Jewish food remained a central component of postwar Jewish identity. In Treasury of Jewish Humor, published in the early 1950s, the folklorist Nathan Ausubel used the term “Culinary Judaism” to refer to a food-based Jewish identity and detailed the lengths to which Jews went to devour their favorite dishes, including delicatessen meats.46 As the sociologist Seymour Leventman put it, a “gastronomic syndrome” could be diagnosed among Jews, one that “lingers on in the passion for bagels and lox, knishes, blintzes, rye bread, kosher or kosher-style delicatessen, and good food in general.”47

In order to survive the transformed gastronomic landscape in which the relatively few Jewish delicatessens that opened in the suburbs found themselves, they needed to appeal to non-Jews as well as Jews. But they also did not want to alienate their base of Jewish customers by serving food that was so nonkosher that it would offend them. It was this balancing act, the historian Ruth Glazer (who later became Ruth Gay, when she married the historian Peter Gay) recalled, that her father engaged in when he opened an “unreconstructed” delicatessen at the end of a subway line in Queens. A kosher delicatessen sporting a sign with Hebrew letters, he was informed, would turn these non-Jews against him from the beginning. And most of the Jews no longer kept kosher or wanted to be seen eating in a kosher establishment.

So he opened a “kosher-style” delicatessen, in which traditional Jewish foods were served but the meat was not kosher. Jewish women felt free to come in to ask for advice on how to prepare Jewish food, while increasing numbers of non-Jews, who originally viewed the deli as a “curiosity,” submitted to the entreaties of Jewish friends to come in and order pastrami, a word that they often mispronounced in amusing ways. Nevertheless, according to Glazer, the store became for Jews and non-Jews alike a “symbol of traditional Jewish living,” despite its departures from fidelity to Jewish dietary law.48 If the fare at Glazer’s father’s delicatessen created such harmony between the Jews and non-Jews of the town, the New Haven attorney Samuel Persky joked, perhaps anti-Semitism could be combated if, rather than “distributing educational pamphlets dedicated to the truth about the Jew, we can so manage it that every rock and rill in this land of liberty be permeated by the gracious aroma of hot corned beef and pastrami.”49

The Rise of Ethnic Food

With the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, the rise of the civil rights movement, and the involvement of the country in Vietnam, the carefree ethos of the early 1960s began to dissipate. The burgeoning interest in multiculturalism, however, meant that ethnic food rose in popularity; the food historian Warren Belasco has insightfully compared the rise of ethnic food with the popularity of oak furniture—both spoke to consumers’ desire for the sense of security that they identified with traditional ways of life.50 Belasco attributes the interest in ethnic food to a host of factors, including the spread of foods from one ethnic group to another (for example, “in-migrating blacks [who] sampled out-migrating kosher foods”), the growth of tourism, and the presentation of ethnic foods in the mass media—especially in relation to ethnic movie and television stars.51

Indeed, people in the 1960s counterculture who resisted the “cultural imperialism” that was destroying local foodways around the globe and replacing them with standardized American foods founded a “countercuisine” based largely on ethnic foods. As Belasco puts it, while the first generation had made food from scratch, the second generation sought “old-style sauces to put on American meats and vegetables,” and the third generation purchased “fully processed convenience foods with an Old World aura that could be supplied with a few spices and a picturesque aura.”52 Many ethnic foods were produced by large corporations, including the Pizza Hut chain and R. J. Reynolds’ Chun King line of Oriental food; Chun King trumpeted a “new mood in food” as the impetus for the spread of Chinese food throughout the land.53

Delicatessen foods were no exception to the commodification of ethnic foods; in 1968, Hebrew National was sold to Riviana Foods, which was itself acquired by Colgate-Palmolive, a soap and toothpaste company.54 (The Pines family bought it back in 1980; by 1986, the company was producing half a million frankfurters a day in its plant in Maspeth, Queens.)55 Savvy young entrepreneurs who founded smaller ethnic-food companies could make a quick profit by selling out to bigger companies.56 Jewish foods, like other ethnic foods, were commodified and torn from their original social context. The pastry-wrapped “deli sandwiches” sold under the Campbell’s Pepperidge Farm and Nestlé’s Stouffer’s brands had as much relationship to a real New York delicatessen sandwich as frozen burritos did to authentic Mexican cuisine.

But it was Chinese food that most captivated American Jews. According to the blogger Peter Cherches, Chinese food was a “birthright” for Brooklyn Jews of his generation; he recalls being “weaned on chicken chow mein.”57 And if a rabbi needed to find ten Jews for a minyan (prayer quorum), what better place to look than in the local Chinese restaurant? In an updating of the phenomenon of “cross-over eating” found by Donna Gabaccia at the turn of the twentieth century, one ethnic group began to define itself through the consumption of another ethnic group’s food.58 The critic Neil Postman recalled that the shopping district in Flatbush, where he grew up during the Depression, boasted appetizing stores, two kosher delicatessens, three candy stores, and a “very popular” Chinese restaurant. On Friday nights, he and his older siblings had a ritual of bringing a dollar to the Chinese restaurant to buy three dinners for thirty cents each, which included egg drop soup, an egg roll, and chow mein.59

Many theories have been propounded to explain the intense Jewish fondness for Chinese food. Gaye Tuchman and Harry Gene Levine, the authors of a landmark study on the subject of New York Jews eating Chinese food, noted that Chinese food was appealing to Jews who, while not keeping strictly kosher (or keeping kosher at home but not away from home), avoided the overt consumption of pork and shellfish. Tuchman and Levine dubbed it “safe treyf”—food that was so thoroughly diced and chopped that it was not recognizable as nonkosher. Chinese food thus, according to Tuchman and Levine, became a “flexible open-ended symbol, a kind of blank screen on which [Jews] projected a series of themes relating to their identity as modern Jews and as New Yorkers”60—one that replaced the equally blank screen or palimpsest of the pastrami sandwich. Through the consumption of Chinese food, Tuchman and Levine suggest, Jews were able to perceive themselves as more sophisticated and urbane, despite the fact that the food was inexpensive and relatively simple. As the British social anthropologist Allison James notes, in writing of magazines and television programs about foreign cuisines, such cultural products paved the way to a “culinary, expatriate, cosmopolitanism.”61

Others have speculated that Jews felt an affinity to the Chinese, since both were ethnic outsiders in Christian America. The Chinese are often called the “Jews of the East,” and in America they became even more marginalized. Tuchman and Levine note that eating in Chinese restaurants “did not raise the issue of Jews’ marginal position in a Christian society” because the Chinese were even more marginal than the Jews were.62 Indeed, Jewish patrons could feel superior to the Chinese. They could even insult the waiter, turning the tables on the treatment they received in Jewish delicatessens.

As Philip Roth put it in his 1967 novel Portnoy’s Complaint, “Yes, the only people in the world whom it seems to me the Jews are not afraid of are the Chinese. Because, one, the way they speak English makes my father sound like Lord Chesterfield; two, the insides of their heads are just so much fried rice anyway; and three, to them we are not Jews but white—and maybe even Anglo-Saxon.” The idea that Jews could be actually taken for Protestants by the Chinese was especially appealing: “Imagine! No wonder the waiters can’t intimidate us. To them, we’re just some big-nosed variety of WASP!”63 Both the Jews and the Chinese operated on a different calendar than Christians did; this was why the biggest night of the year for Jews to eat out in Chinese restaurants was Christmas Eve, a night when most other restaurants were closed. But in addition to serving as this once-a-year gathering place, the Chinese restaurant to some extent also displaced the deli as the weekly Sunday-evening gathering spot for Jewish families.

Of course, Jews still knew, as much as they tried to pretend otherwise, that they were eating forbidden foods. As the old Yiddish saying goes, Az men est chazzer, zol rinnen iber der bord—“If you’re going to eat pork, you might as well eat it until it runs over your beard.” In other words, if you are going to sin, you should enjoy it! Guilt, according to a Canadian rabbi, is a “terrific condiment.”64 On the other hand, as the food scholar Miryam Rotkovitz has noted, the very fact that Chinese food was taboo made the experience of eating in a Chinese restaurant more exciting; it “contributed to the exoticism of the experience.”65

The craze among Jews for Chinese food led to the first cookbook of kosher Chinese food, written by Ruth and Bob Grossman; it presented whimsical recipes that mingled Jewish and Chinese ingredients, such as Foh Nee Shrimp Puffs, which were fried balls of gefilte fish served with hot mustard and plum sauce.66 Furthermore, the opening of kosher Chinese restaurants made it possible for observant Jews—many of whom had grown up in nonkosher households in which Chinese food was a staple and only later embraced Orthodox Judaism—to enjoy Chinese food as much as their less religious coreligionists did.

The marriage of delicatessen and Chinese food had been solemnized on the Lower East Side at Schmulka Bernstein’s (later Bernstein on Essex), a kosher delicatessen that was opened in 1932 by Sol Bernstein, who adopted his father’s name—his father was a butcher and meat manufacturer—as the name of the restaurant. Starting with a small seven-table establishment on Rivington Street between Essex and Ludlow, he moved to 110 Rivington Street, with a factory in the same building, the factory entrance being on Essex Street. The deli expanded in the 1950s by breaking through the wall and taking over the factory space, pushing the factory out to Utica Avenue in Brooklyn.

Bernstein’s daughter, Eleanor, was brought up in an apartment over the store. “My mother never forgave my father for going into the deli business,” she recalled. “When they got married, he was planning to be a doctor, but once he got to medical school, the cadavers upset him. But he joked that he was still an M.D.—a meat dealer!” The deli became known for its specially spiced Romanian pastrami, which other delis tried to copy. It also smoked a lot of geese for the winter holidays; smoked goose was popular among Germans for Christmas and had thus become a favored Chanukah dish for German Jews. In 1960, Eleanor’s father realized that Jews liked Chinese food, and he called an agency that sent him a Chinese chef one day a week. “The Chinese chef came in like a doctor with a little case,” she said. “He wanted to use his own knives, but the rabbi told him that everything had to be kosher; he gave the chef a lesson about all the special rules. My father took the chef to the restaurant supply stores on the Bowery and bought him whatever he needed.” As demand grew, the restaurant hired more Chinese chefs, until the fateful day when, as Eleanor put it, “a war broke out in the kitchen between the Shanghai and the Cantonese, and my father had to fire everyone—-which wasn’t easy, because they were in a union—and start over.” Over time, the restaurant grew to the point that there were 52 people working in the kitchen and a total of 220 in the store.67

The delicatessen had two different menus—one for the traditional Jewish offerings and one for the Chinese ones. A sample Chinese menu from Bernstein’s on Essex St. from the early 1960s (“Where West Meets East for a Chinese Feast and Kashruth Is Guaranteed”) trumpets the fact that “for the first time,” the “Orthodox Jew or Jewess can taste the food specialties of the Orient,” advising patrons to begin with soup before proceeding to appetizers—egg rolls, spare ribs, or “sweet and pungent” veal—and then on to the main course and dessert. The menu also suggests that each party order a variety of dishes to share, a practice that became so popular that later generations would take it for granted.68

Bernstein hired Chinese waiters and gave them tasseled skullcaps to wear, so they looked like Chinese Jews. He sent his chefs to famous Chinese restaurants such as Pearl’s to try their dishes and adapt them to a kosher menu. Although Bernstein would never eat in a nonkosher restaurant, he would occasionally accompany his staff on these spying missions; he would order one of the restaurant’s signature dishes and poke through the food with his chopsticks until he figured out the ingredients so that he could create a kosher version. Even in the Chinese menu at Bernstein’s, the dishes frequently melded Chinese food—or at least the Americanized versions of Chinese food—with eastern European Jewish food. Among the specialties of the house were salami fried rice, egg foo yung with chicken livers, and Stuffed Chicken Bernstein—a half chicken stuffed with bamboo shoots, water chestnuts, and pastrami. Israeli beers and wines were on the drinks menu, along with German beers and domestic kosher wines.

Jews and Italian Food

Italian cuisine was also extremely popular in Jewish communities. Jews and Italians, who often looked similar, both arrived on these shores in large numbers in the last two decades of the nineteenth century. The Jewish section of the Lower East Side was right next to Chinatown, but it was also adjacent to the immigrant Italian section, known as Little Italy, which had a large Sicilian and Neapolitan population. Italians and Jews went to school together, played on teams together, and occasionally ate in each other’s apartments, as in the chapter in Henry Roth’s classic Lower East Side Jewish immigrant novel Call It Sleep, in which the main character, David Schearl, is served crabs by his new Italian friend, Leo. David is afraid to eat the unfamiliar, clearly nonkosher delicacy, but Leo, sucking on a claw, boasts, “We c’n eat anyt’ing we wants,” adding, “Anyt’ing that’s good.”69 At the turn of the century, according to Philip Taylor, “a Jewish boy . . . could easily recognize an Italian district into which he had strayed, by the sight of certain sausages and cheeses in shops.”70

Italians in Red Hook and Canarsie were not far from the Jewish neighborhoods in Brownsville, Bensonhurst, and Brighton Beach. Jews and Italians were known for getting into conflict over religion, with frequent street fights between the children of the two groups. But by the 1950s, Daniel Rogov recalls, the Italian kids would tag along when the Jewish kids went on quests to eat a hot dog in each of the six delicatessens in the Brooklyn Heights area; if they got into a fight, it was “more like playing stickball” than actually fighting, in the days before gang wars with tire chains.71

Both Jews and Italians loved to eat, and both groups were enraptured by, and obsessed with, the sheer quantity of food that was available in America—the meat, the fish, the coffee, the rich desserts. They also both enjoyed a highly theatrical approach to dining. Mamma Leone’s, the Italian restaurant in the theater district, had extravagant decor, nude statues, singing waiters, and huge quantities of highly Americanized Italian food including spaghetti and meatballs, veal Sorrentina, clams casino, and shrimp scampi. Jewish and Italian families both prized dinnertime as the most important daily occasion.

The historian John Mariani could be writing equally about Jews in noting that in Italian households “the dinner table, not the living room, was the center of political and social discourse that raged on for hours and into the night, until one or another family member collapsed on the couch.”72 Rabbi Eric Cytryn recalled that while there was a kosher deli right around the corner from his house in Westbury, Long Island, his family usually gravitated to a local Italian restaurant instead, even though since they kept kosher, they could not eat any of the meat or shellfish on the menu.73

Beginning in the 1970s, Italian restaurants became increasingly fashionable in New York. Mimi Sheraton, the New York Times restaurant critic who happened to be Jewish, relentlessly championed restaurants such as Il Nido and Il Monello that served upscale Northern Italian cuisine, which was a far cry from the pasta and red-sauce-based Southern Italian cuisine that was familiar to most Americans. Even the typical neighborhood Italian restaurant with the red checkered tablecloth and bottle of olive oil on the table was getting rid of its pizza oven and expanding its veal and chicken offerings.74 Sheraton interviewed the comedian Alan King at Il Nido; he talked about growing up in a kosher home but later developing a taste for many different kinds of food, from Italian to Japanese.75

By the 1980s, fashion industry executives, or “fashionistas,” many of whom were Jewish, patronized Tuscan restaurants, where they shook hands on deals to import high-end Italian silk garments and leather shoes made by Prada, Ferragamo, Versace, and other companies. One Italian restaurant in particular, Da Silvano, was a hangout of the crowd from Vogue magazine, where the nation’s fashion styles were set.76 By comparison, Jewish delis never developed into “white tablecloth”–type restaurants where important business deals would be struck. But despite the attraction of other ethnic cuisines, many Jews often felt themselves irresistibly pulled back to a deli. The Jewish sculptor Louise Nevelson, for example, favored Italian food (particularly lobster, veal, or angel’s hair pasta with pesto sauce), although she also often sought out Mexican, Indian, and Japanese restaurants. But when she felt sad, she headed straight for a deli, where she enjoyed “mounds of sour pickles, pickled green tomatoes, rye bread and even pastrami if it’s good and spicy.”77

Multiculturalism and the Deli

With the 1976 publication of Irving Howe’s World of Our Fathers, the first comprehensive history of immigrant Jewish life in New York, Jewish tourism to the Lower East Side boomed with suburban Jews trying to recapture their roots. This nostalgia- and heritage-based tourism was part of a larger multicultural movement within society that also boosted the popularity of the television miniseries Roots (about African American history). World of Our Fathers was published at the same time as the bicentennial of the United States, as the whole country was celebrating its past.

That past, for many Jews, led back to the Lower East Side. As Ari Goldman of the New York Times noted in 1978, the immigrant ghetto “has always been famous for its Sundays. The wares from the shops on Orchard Street spill out onto the sidewalks, the delicatessens on Essex Street can’t make the pastrami sandwiches fast enough, and the smell of pickle brine is heavy in the air.”78

New York Jews’ “tourism” to the Lower East Side dates back to the 1920s, when the children of Jewish immigrants who had grown up in the neighborhood first turned the ghetto into a place of pilgrimage, converting, in the words of Jenna Weissman Joselit, a “slum” into a “shrine.”79 In 1954, the nineteen-year-old Polish Jewish immigrant Abe Lebewohl had gotten his first job working as a soda jerk in a Coney Island delicatessen. Eager to learn the business, he volunteered to spend his lunch breaks working behind the counter. Before long, he became a counterman. He then saved up enough money to buy a ten-seat luncheonette on East Tenth Street, which, by dint of years of labor and more than one major expansion, eventually blossomed into the Second Avenue Deli, the landmark delicatessen on the Lower East Side, complete with a room that paid tribute to Molly Picon (the beloved Yiddish actress) and a “Walk of Fame” outside in which Yiddish actors had stars imprinted on the sidewalk.

But the Lower East Side faded as a part of Jewish life as new immigrants, especially Puerto Ricans and Asians, moved in and the city redeveloped the district with high-rise buildings. By the 1970s, it was the grandchildren of Jewish immigrants who began this process anew, rediscovering the Lower East Side as a source for nostalgia. Especially on Sunday afternoons, Hasia Diner has written, Jews made the stores and restaurants of the Lower East Side into pilgrimage sites, places to take their children and to recapture their childhoods.80 The humorist Calvin Trillin confessed in 1973 that he often repaired on Sundays to Katz’s, where the countermen “always maintain rigid queue discipline while hand-slicing a high quality pastrami on rye.” He described the forbidding sandwich makers as appearing practically to “loom over the crowd—casually piling on corned beef, keeping a strict eye on the line in front of them, and passing the time by arguing with each other in Yiddish.”81

For the Second Avenue Deli’s twentieth-anniversary celebration in 1974, the restaurant rolled back its prices to what they had been when it first opened. Customers flocked in for the fifty-cent corned beef sandwiches, thirty-cent bowls of matzoh ball soup, and nickel cups of coffee. Lebewohl kept coming up with new ways to get publicity. In 1975, with the city on the verge of bankruptcy, Lebewohl gave all the proceeds from two days of salami sales to the municipal coffers. And he ignored the late-1970s gasoline shortages by hiring a horse and buggy—covered with signs promoting the delicatessen—to make deliveries.82

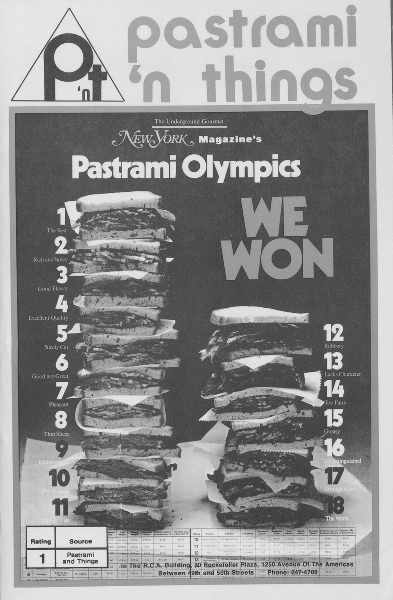

The less that Jews and non-Jews consumed pastrami sandwiches on a regular basis, the more that delicatessen food became special—it was transformed back into a “delicacy” in Jewish culture. Which pastrami sandwich was the “best” became a topic of heated debate; in 1974, New York magazine held a Pastrami Olympics in which the height of each sandwich was carefully measured, along with the weight of the bread, weight of the meat, and cost of the meat per pound; the winning deli was Pastrami ’n Things in Manhattan. And the New York Times restaurant critic Mimi Sheraton bought 104 corned beef and pastrami sandwiches in 1979 to discover her own favorite, in both taste and construction (she dubbed Pastrami King in Queens, the Carnegie Deli, and Bernstein on Essex the best of the lot; Katz’s was at the bottom of the list).83 But these competitions underscored the fact that pastrami had come full circle; it had become, as originally both in eastern Europe and on the Lower East Side, a special-occasion food—to be savored as an occasional treat rather than as a regular part of one’s diet.

Cover of Pastrami ’n Things menu, showing New York magazine poster of the 1973 Pastrami Olympics (Collection of Ted Merwin; rights courtesy of New York magazine)

Nevertheless, the delicatessen sandwich remained an all-purpose, universally recognizable symbol of the city, as shown in a 1970 magazine advertisement for Coca-Cola in which a smiling cab driver leans out the window of his yellow cab, holding an overstuffed corned beef sandwich along with his bottle of soda. The tagline, “It’s the real thing. Coke,” in the context of the ad implies that the corned beef sandwich is “the real thing” as well—that it is an authentic symbol of New York.84

Samurai Deli

In John Belushi’s classic 1976 “Samurai Deli” skit on Saturday Night Live, Belushi plays a delicatessen counterman as a Samurai sword-wielding lunatic. A customer, played by the Jewish comedy writer Buck Henry, is concerned that the corned beef sandwich that he has ordered will give him heartburn and high cholesterol, but the owner, who speaks only Japanese, is a purist; he threatens to commit hara-kiri when the customer asks him to trim off the fat.85 The customer withdraws his request, but when he asks the counterman to break a twenty-dollar bill, the counterman does so with his sword, demolishing the counter in the process.

The stereotypes of the deli are neatly inverted in this parody. The deli is no longer viewed as a haven; the deli owner, rather than being kindly and talkative, is homicidal and inarticulate. (He speaks no English, like the immigrant delicatessen owners who spoke only Yiddish a century before.) The deli is a place of violence and fear, and the food that it serves is so unhealthy as to be downright poisonous. It is difficult to see which is more dangerous, the food itself or the lunatic who serves it. Alan Zweibel, who wrote the skit, told me that his idea was to invert the idea of the friendly local delicatessen, turning the act of ordering food there into a terrifying experience.86

The episode, which was one of many Samurai spoofs that Belushi and Henry did, spoke to the mushrooming anxiety about health and fitness that characterized the 1970s; it also ran just as reports of mercury contamination in supermarket products caused widespread alarm about the nation’s food supply. A skepticism about the efficacy of modern medicine, along with a developing focus on self-improvement and self-fulfillment, left many people feeling more responsible for maintaining their own bodies. As Peter N. Carroll has written, the spread of terrifying new viruses and bacterial infections in the 1970s led to what he calls a “thorough reevaluation of the relationship of the human body to the natural environment.”87

A huge diet and fitness industry developed, centered around providing health clubs, exercise equipment, nutritional supplements, and low-calorie foods. By the 1980s, according to the sociologist Barry Glassner, the fit body held a “signal position in contemporary American culture—as locus for billions of dollars of commercial exchange and a site for moral action.”88 As Jews, including the Orthodox, jumped on the health and fitness bandwagon, they looked to develop healthier, more gourmet versions of traditional Jewish dishes.

In line with Americans’ newfound “duty” to their own bodies, an estimated one hundred million of them were dieting. Companies began marketing low-fat, low-cholesterol, and low-sodium foods; by the middle of the decade, these “diet foods” were a $700 million business, compared to a $250 million business in the late 1950s. While “reducing salons” first became popular in the 1950s, they had been marketed primarily to women. The new emphasis on fitness extended to men as well. It was recommended that both men and women “exercise in qualitatively the same ways (with the same movements, using the same equipment or games) and in the same quantities, they should eat the same healthful foods, and subscribe to the same values, such as naturalness, self-control, and longevity.”89 Athletic equipment was a $2-billion-a-year industry, while Jim Fixx’s The Complete Book of Running was a runaway best-seller.

In such a climate, delicatessen foods were considered the opposite of what both men and women needed to eat in order to preserve their health. Six of the ten leading causes of death—including heart disease, cancer, obesity, and stroke—were linked to diet.90 For those who were on a salt-restricted diet, the Consumers Union recommended, foods to be avoided included smoked or prepared meats such as bacon, bologna, corned beef, ham, liverwurst, luncheon meats, pastrami, pepperoni, and smoked tongue.91 For those who insisted on continuing to eat deli meats, experts recommended switching to pastrami, salami, and bologna made from turkey. Putting delicatessens in the same category as fast-food eateries, the food columnist Barbara Gibbons called on both kinds of restaurants to “shape up!” reporting that the “disenchanted are staying away in droves after a decade of bad-mouthing from nutritionists, consumerists and food critics.”92

Robert Atkins, who first introduced his high-protein, high-cholesterol, low-carbohydrate diet in 1972, bucked the trend by proclaiming that fatty foods were good for you. Atkins was in many ways simply adapting Dr. Irwin Stillman’s high-protein diet from the late 1960s, which Stillman touted both in a best-selling book and on late-night television. But Atkins lauded Jewish deli food in particular, explaining that his diet permitted not just lox and eggs but “cold cuts galore—brisket, tongue, corned beef, pastrami, turkey.” He warned that dieters “avoid the coleslaw; it’s made with sugar,” but he invited them to “make free with those crisp, fragrant new dill pickles.”93

Beef consumption, which had increased every year until 1975, suddenly took a nosedive, as men between the ages of nineteen and fifty cut their intake of beef, including deli meats, by a third. Francis Moore Lappe’s best-selling book Diet for a Small Planet, published in 1971, argued that by feeding grain to animals, whose meat contains far fewer nutrients than the feed does, the United States wasted tremendous natural resources and perpetuated world hunger. Nor was this wholesale destruction limited to this country’s borders; the cutting down of the rain forests in Brazil was blamed on the need to graze cattle to satisfy the fast-food market in America. And cows were also blamed for producing so much methane gas, mostly from belching and farting during rumination, that the greenhouse effect was dramatically intensified.94

Some people argued that at least the deli food sold in supermarkets was healthier than that traditionally purveyed by delis. For example, while delis sold frankfurters with natural casings (made from sheep intestines), the supermarkets offered the healthier, skinless variety. “You got a snap from a deli hot dog that you couldn’t get from a skinless one,” Skip Pines of Hebrew National admitted, even as he banked on the supermarkets for his company’s future. Pines himself stayed healthy through portion control; he ate a single hot dog every day for lunch and then snacked in the late afternoon on a slice of salami, which he tested for the three essential qualities of “flavor, grind, and nuance.”95

In addition to marketing their deli products on the basis of health, supermarkets also continued to advertise them on the basis of quality, convenience, and price. In the late 1970s, a newspaper ad by the Stop & Shop Supermarket in the local newspaper in Norwalk, Connecticut, urged consumers to “set aside a special ‘get out of the kitchen night’” on a weekly basis. “Everything we make in our kitchens is just as good as the best New York Deli, but a lot less expensive.” The ad suggested a Reuben sandwich with corned beef, coleslaw, and pumpernickel with Russian dressing or a jumbo club sandwich of roast turkey breast, baked ham, and Swiss cheese on rye—with the meat sliced “fresh to order” by its “deli people.”96

As the twentieth century wore on, humor about the unhealthiness of Jewish deli food took on a sharper, more satiric edge. In Leonard Bernstein’s short story “Death by Pastrami,” a funeral salesman named Fleishman markets his services to deli patrons just after they polish off six-inch-high sandwiches; he bribes the waiters to tell him who ordered pastrami. But as more salesmen discover the scheme, the people eating in the delis begin to feel too self-conscious to eat in the restaurants, and his business takes a nosedive.97

Finally, concerns about the deleterious effects of Jewish food on the body animate a Seinfeld episode in which George’s father, played by the comedian Jerry Stiller (who earned an Emmy Award for his performance in the episode), panics that he has poisoned the members of a singles group by serving them spoiled kreplach, which triggers traumatic memories of his serving contaminated meat to his platoon during the Korean War.98 The stereotype of delicatessen food as unhealthy, which had dogged it as far back as the immigrant period, now dominated most Jews’ perceptions of this type of food.

“Comin’ through the Rye”: Delis in Popular Music

By creating Jewish parodies of popular songs, Jews fantasized that the whole world had become Jewish. The masters of this form of comedy, both of whom referred almost obsessively to deli food in their work, were Mickey Katz and Allan Sherman.

Katz began his career as a clarinetist in Cleveland but soon found work with the Spike Jones orchestra, which was known for its send-ups of popular songs. Katz first invented a klezmer-inspired, Yiddish version of “Home on the Range,” which he followed with “The Yiddish Mule Train,” “Kiss of Meyer,” and “Duvid Crocket,” all of which sold tens of thousands of copies. Much of his success came from the quality of his orchestra, which included Mannie Klein (later replaced by Ziggy Elman) on trumpet, Si Zentner on trombone, and Sam Weiss on the drums.

Jewish food was a constant theme of Katz’s Rabelaisian humor. Josh Kun has noted that Katz’s parodies are invariably based on the “‘substratum laughter’ produced by food—gribbenes, matzoh, schmaltz, pickles, kishka, bagels, latkes—and its digestive impact on those who consume it.”99 What could Jewish humor be based on, at a time when many Jews were not well versed in their own tradition? Even if they no longer spoke Yiddish and had never learned much Hebrew, they could speak deli—the universal language of American Jewishness. Kun views Katz as resisting Jewish assimilation by insisting on the Jew as outsider, as on the cover of one of his albums, Borscht Jester, in which the musician is shown in cap and bells, holding a salami.

Katz seemed unable to resist incorporating references to Jewish food in almost every song, no matter how incongruous the reference. In his recordings and performances, including a short-lived 1951 Broadway show called Borscht Capades, Katz performed songs such as “Halvah Hilarities,” “Matzoh Ball Jamboree,” “Farfel Follies,” and “Chopped Liver” (based on “Moon River”). In his version of the end of Al Jolson’s “Toot, Toot, Tootsie,” he substituted “I’ll send you some pickles and rye” for Jolson’s famous extended warble “Goodby-y-ye.” Katz combined klezmer with swing, calypso, polka, mambo, opera, and rock music. Katz’s music provided what must have felt like an easy fix, a quick detour into memory lane before getting back on the road to success in American society.

Katz’s successor in the business of Jewish song parodies, the aforementioned Allan Sherman, was born Allan Copelon in Chicago in 1924, the son of the racing-car driver and automobile-garage owner Percy Copelon and his wife, a flapper named Rose Sherman. Sherman’s parents divorced when he was six years old; he lived with his mother and eventually adopted her maiden name. Expelled from the University of Illinois for breaking into a sorority (for the purpose, he said, of using the phonograph player), Sherman ended up performing song parodies at a bar in Chicago, before finding work in New York writing jokes for various radio and stage comedians, including Jackie Gleason and Jack E. Leonard. In the early days of television, he was also a writer for variety shows such as Cavalcade of Stars and Broadway Open House.

Sherman’s first album, My Son, the Folksinger, took the nation by storm; it became the fastest-selling album in recording history, eventually selling more than a million copies. When this short, obese man with heavy glasses with a raspy voice took American folk or Broadway songs and set them to lyrics about deli food, he showed that Jews still maintained an ethnic consciousness even while Jewish culture appeared to be increasingly subsumed under the overarching Judeo-Christian ethos. In his song “Shticks of One Kind and Half a Dozen of the Other,” on his 1962 album My Son, the Celebrity, he sang, “Do not make a stingy sandwich / Pile the cold cuts high / Customers should see salami / Coming through the rye.” The salami (read: Jewishness) erupted through the rye (read: American society), bringing Jewish culture to the fore.

By changing “Moon River” (from the film Breakfast at Tiffany’s) to “Chopped Liver,” “With a Little Bit of Luck” (from the Broadway musical My Fair Lady) to “With a Little Bit of Lox,” and “Water Boy” (a southern African American song) to “Seltzer Boy,” Sherman exploited not just the humorous associations of delicatessen foods but the sense that Jews were transforming American culture in their own image. According to Sherman’s biographer, Mark Cohen, while Sherman’s delicatessen-themed musical The Golden Touch never made it to Broadway, its “suspicion of success, encouragement to remain true to oneself, and proud assurance that chopped liver and other homely hallmarks of Jewish life were worth keeping . . . remained the themes of Sherman’s life.”100

While the author Ken Kalfus has suggested that Sherman made Jewish humor “mainstream,” he also notes that Sherman emphasized Jewish particularity. In Kalfus’s words, it “expressed Jews’ apartness from American culture, at a time when the culture itself was about to go counter.” Kalfus writes perceptively about the emphasis placed at the time on the “lovability of the loser,” cataloguing such bumblers and bunglers—both real and fictional—as the 1962 Mets (40 wins, 120 losses), Alfred E. Neuman, Charlie Brown, and Jerry Lewis.101 In any event, Sherman turned Jewish food into comic gold in a way that transcended its Yiddish origins and made it accessible and humorous to both Jewish and non-Jewish Americans. As the critic Gerald Nachman has pointed out, Sherman “resisted being branded a ‘Jewish’ performer, as his repertoire played to everyone. . . . His lyrics spread a generous helping of chopped liver over a slice of American cheese. The playful lyrics were a kick, but they also made fun of Jewish (and, by extension, all) middle-class American life in the early 1960s.”102

Love, Sex with the Shiksa, and the Jewish Delicatessen

Another “danger,” that of intermarriage with non-Jews, loomed ominously over the delicatessen. Eating nonkosher delicatessen food had long symbolized having the “forbidden pleasure” of sexual relations with non-Jewish partners. In the 1940s, the novelist Isaac Rosenfeld had famously observed the riveted passersby who watched beef fry (a kosher imitation of bacon) falling off the slicing machine of a window of a Lower East Side delicatessen. Rosenfeld wrote that a crowd, “several rows deep,” constantly gathered to watch this spectacle—“oblivious of the burden of parcels, of errands and of business; no comments are made, they stand in silence, not to interfere with another’s contemplation, as they follow the course of the slices, from the blade to the box.”103

Rosenfeld viewed the trance that the people fell into not in religious terms but in sexual ones; he suggested that the beef fry is an “optical pun” on the concept of treyf and that Jews unconsciously associated eating treyf with sex with non-Jews—unlawful carnal knowledge, indeed! Rosenfeld insisted that anti-Semitism sprang from a misconception among non-Jews that Jews were “lecherous” and enjoyed “greater freedom from restraint.” As Eve Jochnowitz interprets him, Rosenfeld “traces all of sexual pathology to the laws of kashrut,” suggesting that “all anti-Semitism is rooted in gentile myths, all provoked by Jewish food, about Jewish superior sexuality.”104

By the late 1980s, the Jewish-Christian intermarriage rate had skyrocketed from almost nothing at the beginning of the century to about 50 percent, as Jews increasingly sought non-Jewish partners and non-Jews felt more comfortable marrying Jews.105 The trope of the Jewish man and the shiksa (a derogatory Yiddish term for a non-Jewish woman) had become especially familiar in popular culture, especially in the films of Woody Allen. Jewish delis often served as backdrops for relations between Jewish men and their non-Jewish girlfriends, as in Annie Hall, when the main character, Alvy Singer, takes his tall, midwestern girlfriend to the Carnegie Deli as a prelude to their having sex for the first time; she mistakenly orders a pastrami sandwich on white bread with mayonnaise (echoing a scene in the Broadway musical Skyscraper in which Julie Harris commits a similar faux pas in the Gaiety Delicatessen),106 and he grimaces, as if remembering Milton Berle’s classic joke that “every time someone goes into a delicatessen and orders a pastrami on white bread with mayo, somewhere a Jew dies.”

Food and sex are frequently linked in Allen’s films; as Allen’s character in Love and Death quips when his lover invites him to her bedroom, “I’ll bring the sauce.” Or as Allen noted in a parodic New Yorker essay, on food in the world of philosophy, “As we know, for centuries Rome regarded the Open Hot Turkey Sandwich as the height of licentiousness; many sandwiches were forced to stay closed and only opened after the Reformation.” (Indeed, the seventeenth-century philosopher Baruch Spinoza “dined sparingly because he believed that God existed in everything and it’s intimidating to wolf down a knish if you think you’re ladling mustard onto the First Cause of All Things.”)107

But why has Alvy taken Annie to a deli in the first place, if not to shore up his own vulnerable ego? The delicatessen is the one place that is comfortable and familiar for the demasculinized Jewish man and where he can thus feel superior to her and her anti-Semitic family. His refraining from coaching her on what to order, and his thus allowing her to make a fool of herself in front of him, elevates him in his own eyes. It allows him to make love to her from a position of strength rather than of weakness and inferiority.108 The historian Henry Bial views this scene from the dual perspectives of the Jews and non-Jews in the film audience, noting that the non-Jews “learn what it means to act Jewish as the film progresses. . . . Alvy’s rolling eyes and horrified expression are an in-joke to some of his viewers and a ‘teachable moment’ to the rest.”109

This dynamic is neatly reversed in the Katz’s Deli scene in Rob Reiner’s 1989 film When Harry Met Sally—a takeoff of the Woody Allen genre and of Annie Hall in particular—in which the non-Jewish woman, Sally, played by Meg Ryan, shows the egotistical Jewish man, Harry, played by Billy Crystal, that he is less masculine than he thinks he is because he cannot tell whether she is having an orgasm (and, in a sense, that she doesn’t need him at all in order to have it). While the fake orgasm is not related specifically to the food that she is eating (she is eating a turkey sandwich, from which she carefully removes one slice of meat after another before consuming it), it is uniquely appropriate in the deli context—one has the sense that the humor would evaporate if it were shot in a Chinese restaurant with tinkling music in the background. The scene makes hay from the associations that Jewish food has with sex, with vulgarity, with unbridled bodily urges, with the lack of civility and restraint.

After all, the deli—with its casual vibe, lack of tablecloths, and raucous atmosphere—was a place where Jews had celebrated freedom from table manners, from the need to speak softly, and from the oppressive kinds of control over their own physical bodies that they needed to assert in the wider society in order to prevent being viewed as vulgar, uncivilized, and uncouth.110 In the context of the Lower East Side, where Jews had historically lived in overcrowded tenements that afforded little privacy, “private” sexual behavior was often much more “public” than most would have preferred, and the deli was an extension of this private space into the public realm.

Meg Ryan and Billy Crystal in the “orgasm” scene in Katz’s Delicatessen from the 1989 Rob Reiner film When Harry Met Sally (Licensed by Warner Bros Entertainment, Inc. All rights reserved.)

Yet, despite Sally’s explosive, seemingly definitive usurpation of the space, a Jewish woman defiantly has the last word: the well-dressed, elderly customer at the next table (played by the director’s mother, Estelle Reiner) declares in a perfect deadpan, “I’ll have what she’s having.”111 And Jewish women do indeed reclaim the space in the 2007 documentary Making Trouble, in which four female stand-up comics—Judy Gold, Jackie Hoffman, Cory Kahaney, and Jessica Kirson—eat lunch at Katz’s while paying tribute to three generations of female Jewish entertainers in American history, such as Fanny Brice, Sophie Tucker, Joan Rivers, and Gilda Radner.112 But non-Jewish women again take center stage in a flash-mob video from November 2013, in which twenty female customers at Katz’s simultaneously reenact the scene from the Reiner film.113

Broadway Danny Rose, Allen’s black-and-white 1984 film about a hard-luck theatrical agent, opens with a scene of a group of aging Jewish comics—Corbett Monica, Sandy Baron, Jackie Gayle, and Will Jordan—sitting at a table in the Carnegie Deli, swapping anecdotes about their life on the road. They then reminisce about Danny Rose, the agent, played by Allen. Rose has been reduced to representing such clients as a blind xylophone player, a one-armed juggler, a couple who “fold” balloon animals, and a skating penguin dressed as a rabbi.114 The film highlights the waning of secular Jewish culture, using the deli as a symbol of that decline. According to the film scholar Jeffrey Rubin-Dorsky, “what Allen locates in the Jewish world of the Catskills” and, by extension, the Carnegie Deli, “and what Danny Rose recreates with his ragtag band of odd ‘acts,’ is the sense of unforced community that existed among a people gathered together to share a culture that would inevitably disappear in the process of Americanization.” Rubin-Dorsky is struck by Allen’s finding a “nurturing spiritual connection to the Jewish past” through the reiteration of the link between Jewish comedy and Jewish food.115

Jewish masculinity is even more explicitly connected to deli sandwiches in “The Larry David Sandwich,” an episode of Curb Your Enthusiasm in which the main character, Larry David, who grew up in Brooklyn but now lives in Hollywood, decides for once to pray at a synagogue for Rosh Hashanah but finds out that the tickets are sold out and that he will have pay a scalper to gain admittance. His attendance at the service proves to be disastrous and results in his being ejected, along with his non-Jewish wife, Cheryl. Larry seems not to care; he realizes that he prefers to spend his time at his favorite Jewish deli, Leo’s, where he has finally achieved the signal honor of having a sandwich named after him.

Ed O’Ross and Larry David in “The Larry David Sandwich” from season 5 (airdate 9/25/2005) of Curb Your Enthusiasm (Courtesy of HBO / John P. Johnson)

The problem for Larry is that “his” special sandwich is not a traditional meat sandwich but one of sable and whitefish. In being a kind of inauthentic deli sandwich, it thus subtly undermines Larry’s claim to true celebrity, as well as his masculinity, as symbolized by the lack of red meat in his sandwich. The latter point is underlined by the fact that Larry is also afraid to shake hands with the deli owner, Leo, because Leo’s handshake is crushing.

Larry’s attempts to trade sandwiches with Ted Danson, whose namesake is a roast beef, coleslaw, and Russian dressing combo, are fruitless. Larry argues, naively, that Danson should not care what the ingredients of his own sandwich are since Danson doesn’t frequent the deli as much as Larry does or bring his father to eat there; Danson, after all, is not Jewish. But Danson refuses the trade—the fish sandwich sounds terrible and is much too ethnically Jewish, and, in any case, Danson knows a good deli sandwich as well as Larry does. Nevertheless, even as deli food became more mainstream, as Curb showed, it also maintained a strong connection to secular Jewish identity, as one of the few remaining links that Jews like Larry had to their Jewish heritage.116

The episode presents the deli as a more viable Jewish space than the synagogue, where the worshipers are shown as bored and impatient. By contrast, the deli is a shown as a place of fun, fellowship, and humor where commercialism can be openly celebrated in its connection to popular culture. While the same characters, including the deli owner, are also shown at the synagogue, the conversations among them revolve around the deli sandwiches, not the lofty spiritual matters that one might expect them to be discussing on the Jewish New Year.

For these characters to have sandwiches named after them makes them feel that they have achieved true recognition; having other people eating “their” sandwich causes tremendous pride and pleasure. To get “up on the board” in a synagogue might mean having your name on a plaque on the wall; this honor is acquired simply by giving money. But to be “up on the board” at the deli is a sign of real fame.

The Yuppies Rule: The Rise of Gourmet Kosher Food

Beginning in the 1980s, Modern Orthodox Judaism, which promoted the idea that Jews could participate equally in American society and yet still maintain fidelity to religious law, gained strength. While Hasidic Jews had colonized neighborhoods in Brooklyn beginning in the interwar period and had seen their numbers climb dramatically in the years after the Holocaust, it was Modern Orthodox Jews who experienced the most dramatic rise in both visibility and influence.

One leading Orthodox rabbi, Walter S. Wurzburger, was quoted in a front-page article in the New York Times noting that the “vigor as well as the image” of Orthodox Judaism had been “completely revitalized.” Indeed, he crowed, “Gone are the predictions of the inevitable demise of what was widely dismissed as an obsolete movement that could not cope with the challenges of an ‘open’ society.”117

The resurgence of Orthodox Judaism spelled trouble for the typical kosher delicatessen. Many modern Orthodox Jews lacked nostalgia for the forms of Jewish culture that had been so important to their second-generation parents. Unless a delicatessen were glatt kosher, meaning that it adhered to the most rigid standards (including closing on the Sabbath and the Jewish holidays), they would generally avoid eating in it. Even to be seen walking into a non-glatt kosher delicatessen exposed one to the risk of ostracism from the community, under the assumption that observers might be misled into eating there themselves.

Delicatessen food was widely perceived as low class. Bryan Miller, restaurant critic for the New York Times, noting the expansion of kosher dining options in the city, observed that Jews appeared eager to shed what he called the “gastronomic barbells” of delicatessen food. The hearty food served in delicatessens represented, he averred, the weight of the immigrant Jewish heritage, which Jews self-consciously cast off in the act of adapting their heritage to meet the needs of upward social and economic mobility.118

The more “yuppified” that Orthodox Jews became, the more that they tended to disdain the deli. Some restaurants combined deli favorites with other types of food; for example, Jacob’s Ladder in Cedarhurst, Long Island, served not just kosher matzoh ball soup, chopped liver, cold cuts, and potted brisket of beef but also hamburgers, barbequed chicken wings, spareribs, and chicken fricassee. But others avoided deli food entirely and sold more cosmopolitan, gourmet fare. On the Upper West Side, Orthodox Jews flocked to Benjamin of Tudela (named after a globe-trotting medieval Spanish rabbi) for its kosher steaks, chops, duck, chicken, and fish. The restaurant’s brick walls, charcoal-gray rugs, and bouquets of wildflowers all bespoke an affluent clientele.