Figure 1.1. Nouveau plan de Paris avec toutes les lignes du Métropolitain et du Nord-Sud. A. Taride, Paris, 1915 (detail). Bibliothèque Nationale de France (code: GE D-7164).

The wide-eyed child in love with maps and plans

Finds the world equal to his appetite.

How grand the universe by light of lamps,

How petty in memory’s clear sight.

—Charles Baudelaire, “Voyaging”1

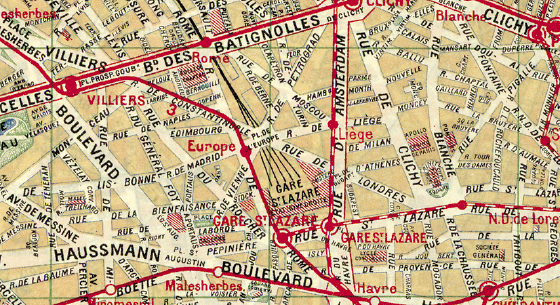

In a celebrated passage from a short article published in 1929, Walter Benjamin imagines the difficulties a tourist in Paris might encounter when looking for points of reference on a blustery and rainy day. The tourist attempts to read a map of the city posted at a windy corner before it is torn or blown away. Finally managing to read it, the tourist, he adds, learns “what a city a map can be. And what a city is.” Thus we can imagine Benjamin, his hand clinging to a Taride map, going about the Quartier de l’Europe near the Gare Saint-Lazare. And we can recall what is unique (and, at the same time, utterly banal) for those who at least once in their lives try to find their way in an unknown city: it is in these very places, by virtue of the map representing the Parisian quarter, that they find their bearings. “Near the great square in front of the Gare Saint-Lazare half of France and half of Europe surround the viewer. Names like Havre, Anjou, Provence, Rouen (for Rome?), London, Amsterdam, run through the gray streets as iridescent ribbons through gray silk. That’s the so-called Europe Quarter. Thus, bit by bit, you can traverse the streets on the map.”2 Yet we cannot tell what Benjamin’s imaginary tourist was really looking at when he was penning these lines, whether it was the map or the street. In question are two simultaneous ways of learning that take place on the terrain itself, that of reading the map and that of reading the city.

A play of reflections and mirrors: the map is a reflection of Paris. With their own eyes tourists can follow the streets on the map that sparkle like silken ribbons in a mirror. But the city is also a reflection, the reflection of greater territories, of France and Europe, to which it refers in the scatter of streets near the Gare Saint-Lazare. Around the station we take a few steps to go from Liège to Milan, then to Athens and London, and we do an about-face to go to Budapest, Vienna, Edinburgh, Lisbon, Madrid, and Naples. Leaving Edinburgh, Lisbon, Madrid, and Naples aside, the Paris that can be mapped in turn becomes a map. Can’t we really say that that Taride map is a map of a map, and the reflection of a reflection? And why wouldn’t the map of the Europe Quarter help in situating me in Europe? Something imaginary circulates in the space of the city (figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1. Nouveau plan de Paris avec toutes les lignes du Métropolitain et du Nord-Sud. A. Taride, Paris, 1915 (detail). Bibliothèque Nationale de France (code: GE D-7164).

However, the street names, and in this instance geographic names, are what drive the imagination, the element allowing passage from one place to another and, at the same time, access to the entire city, its plan, and all of Europe. Benjamin writes: “Entire districts reveal their secrets in the names of their streets.”3 But in Paris, this magical power of street names causing tourists to go from one reflection to another transforms the place into the reflection of another place, and more generally, the city into the mirror of other cities, of a country, and of an entire continent. Noting an Illustrated Guide to Paris, Benjamin remarks, “The passage is a city, a world in miniature.”4 More precisely, by virtue of the geographic names of streets, the city soon becomes a vast map, a reservoir of signs for countless travels and new fictions. And the maps that represent it are maps of this map.

Certain maps also pose logical questions, or else they are fictions that pose philosophical problems. In his novella titled “The Zahir,” Borges relates the story of this painter from the Sind who had drawn in a little cell “a species of an infinite tiger”: “This tiger was composed of many tigers in a vertiginous fashion; it was traversed, striped by tigers, it contained the seas and the Himalayas and armies that resembled tigers.”5 The first thing this painter wanted to do, Borges added, “had been to draw a world map.” Whence a first question: Can a map contain itself?

This question refers to a philosophical tradition that Borges knows well. Its origin is found in a lecture given by the American philosopher Josiah Royce in which the final analysis leads to the notion of the perfect map, in other words to the exactitude of representation in the context of a reflection on systems of self-representation.6 Royce imagines the possibility of drawing a perfectly exact map of England on a part of the very soil of England. If this map is exact, it follows that it must represent in itself another map that represents it in representing England, and in turn this other map contains another, that represents the two preceding maps, and so on up to infinity. Borges thus translates Royce’s remark: “Let’s imagine that a portion of England has been perfectly flattened, and that on it a cartographer draws a map of England. The work is perfect; there is not a detail of English soil, however reduced it might be, that fails to be recorded on the map; everything can be found therein. In this case, the map has to contain a map of the map, which must contain a map of the map of the map, and so on until infinity.”7

Borges applies this philosophico-cartographic hypothesis in relation to other works of literature and painting: the Ramayana, the Thousand and One Nights, Hamlet, Don Quixote, Las Meniñas. In each instance it is matter of imagining a vertiginous experience—that of the infinite—through the intermediary of figurative or narrative means, of a mise-en-abyme, that can also be called a fiction within a fiction, a picture within a picture, a book within a book, a map within a map. What matters with the map of England drawn on the soil of England or with the map of the Empire is space within space, or rather, infinitely, space within space within space, and so on.

I will not dwell further on the logical dimension of the problem of the existence of this paradoxical space that contains and represents itself.8 In a certain way Bertrand Russell solved the problem with his theory of types that Borges quotes elsewhere.9 Royce’s maps are illustrations of the notion of “reflexive class” (classes that contain themselves). Should this kind of paradox be avoided, according to Russell, the self-referential usage of language must be avoided and the levels of enunciation in discourse carefully distinguished. In other words, the map of England and England belong to two different types of reality between which an equivalence—but not an equality—can be grasped.

It might be worth pausing on the consequence that Borges draws from the matter: space that is opened by the map in the map is that of fiction, or better, a space in which the distinctions between reality and fiction are blurred. “Why,” he asks, “are we upset if the map is included in the map and the thousand and one nights in the book of A Thousand and One Nights? I think I’ve found the cause: such inversions suggest that if the characters in a fiction can be readers or spectators, then we, their readers or their spectators, can be fictive characters.”10

If in effect the map and the territory merge, who is going to tell me where I am, where I live? On what territory? Or on what map that represents it? Then who tells me that what I consider to be real territory in all truth is not a map? A representation? Who finally tells me that I am not in the middle of an infinite series of maps fitting into each other, much like two mirrors facing each other yield an infinite series of reflections? What I call real is perhaps nothing other than the map in which I happen to be at this moment. Perhaps, moreover, I am merely an object on a preceding map, just as I would be, unbeknownst to myself, a character whose story is being told at the moment I am living the story, but in a story told by another. At the spot where the map covers the territory (and a fortiori if it covers the entire territory), neither the real nor the image remains, no longer is there a distinction between reality and fiction: everything has become either fiction or reality. This space is indeed utopian, nowhere at all.

Yet surely these logically impossible, paradoxical, and infinite utopian spaces have existed concretely. In this case the logical contradiction is not a practical insufficiency. These maps that are territories that are maps can be traveled just as well in gardens and parks as at the edge of cities. For eons these spaces that are at once maps in themselves have been conceived, projected, and even realized. Projects of this kind have existed since the Serapeum of Hadrian’s Villa at Tivoli, as Jean-Claude Grenier has shown, “put forward as if it were a veritable monumental map of Egypt” to the geographic gardens established in Paris up to the beginning of the twentieth century.11

Even in Europe today people can visit the Swissminiatur at Melide near Lugano, Holland in miniature in the Madurodam Park, Italia in miniatura in Rimini, Catalunya en miniature near Barcelona, Portugal dos Pequenitos in Coimbra, France miniature located in Élancourt near Paris, but also discover Alsace in the Parc des miniatures in Plombières-les-bains, the Val de Loire in Amboise inside the Parc des Mini-Châteaux, or even the landscapes of Saxon Switzerland in the Miniaturpark die kleine Sächsische Schweiz near Dresden. And there is also a Miniatürk near Istanbul, a miniature park of Silesian monuments near Wrocław in Poland, and no less a Russie miniature in Saint Petersburg. For a long time Europe has been visualized in Brussels in the Mini-Europe park situated near the Atomium. Whoever wants to see the world will go to the Beijing World Park or, not far away, near Shenzen, to the Windows of the World, or even to the Tobu World Square in the Tochigi Prefecture in Japan, but also to the Minimundus of Klagenfurt in Austria, even to the Swiat Marzen located in the province of Malopolska in Poland (where too Poland can be visited in miniature). Eleven countries are represented in the World Showcase at the Epcot Park in the heart of Orlando’s Walt Disney World. Moreover, a few of these parks, like France miniature or Italia in miniatura, draw attention to the cartographic form of their plan. The analogical and mimetic drive seems to have been pushed to its limit. France miniature resembles France, or rather a map of France (figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2. La France miniature. Google Earth.

Those who visit the park walk about in a map that, when all is said and done, is also a territory. They visit a map and they visit the territory that it represents. They discover a touristic geography in the walkways of the park that are structured around the major rivers (Loire, Rhône, Garonne, Seine), architectural schemes and exemplary technical achievements (the Eiffel Tower, the Versailles Castle, the Stade de France, the Garabit Viaduct, etc., among a total of 116), and large regional sections (the North and the Île-de-France, the East, Southwest, Center, West and Southwest). Yet must these disproportionate maps—whose projects endlessly follow one after another—also be considered vertiginous objects resembling the figure of an infinite tiger? To be sure, the existence of these spaces comprises a kind of counterhistory of cartography that continues to move alongside the scientific history of cartography. But what kind of epistemology and ontology would be needed to account for these spaces that are at once realized fictionalizations and fictional realizations? It goes without saying that in view of such “limit objects” the simple opposition between reality and fiction is inadequate, and as a result there needs to be recognized, at the very core of seemingly time-tested realities, the presence of zones of fiction. In the same way fiction will need to be seen as a dimension of our reality.

As Christina Ljungberg writes, “In fiction, maps have often been used as statements and as assertions of authenticity.”12 Maps (whether topographic or geographic) fill this function of authentification because, providing a reference to the work of fiction, they tie the work to a “reality” designated as foreign to the text; they anchor the fiction in a spatial and temporal reality to what elsewhere readers feel they can gain access. What fiction describes or reports having taken place took place because it is there, right where it is shown and designated by the map. It is as if Aristotle’s assertion had to be verified: every being is somewhere (Physics, IV, 1), and to exist is to have a place. When the map shows the place told in the story it becomes in a certain way the very proof of the story.

Maps, however, not only attest to existence. They are also the operators of reading and understanding. We know well the famous formula that Flemish cartographer Abraham Ortelius set on the frontispiece of his Parergon: “Geography is the eye of history.” Since the beginning of modernity, it is a commonplace in geography: to read histories, be they legendary, civil, or religious, a map is needed to visualize the places where these histories took place. Allowing the reader to see the places, the map also makes the action easier to follow and understand. Thus,

in reading about Saint Paul’s travels from the city of Jerusalem to Rome, should the reader be informed by means of the map in what place in the world Jerusalem is situated, and how the islands of Cyprus, Rhodes and Malta follow; that in sailing to the aforesaid Islands and in their presence, he finally arrived in Rome: not only will he better understand the voyage stated above, but also retain it in memory for a longer time and will be enabled to relate it in words more graciously, to explicate it, to have it understood by others.13

When placed before the eyes of the reader consulting the folio that Ortelius published in 1579, the map of Saint Paul’s voyages thus acquires a kind of visual evidence. It would also be the case for the ancient history of Italy, Greece, Egypt, and Palestine, for the life of Abraham, for the peregrinations of Ulysses and Aeneas, for the adventures of the Argonauts, for the conquests of Alexander the Great, all of whose maps Ortelius progressively assembles in the Parergon.

The service that cartography renders to reading also holds for literature. It is impossible to count the number of maps drawn and printed to accompany the reading of novels. Thus for example, as Roger Chartier has noted, the editions of the Orlando furioso published by Valgrisi in 1556 and 1573 contain several geographic maps allowing readers to follow the travels of certain characters.14 In the same way, inaugurating a long tradition, Spanish geographer Tomas Lopez proposed a “Map of a Part of the Kingdom of Spain Containing the Lands Traveled by Don Quixote” for the edition of the Real Academia Española of 1780. Therein are drawn the itineraries of three “sorties” and then pinpointed thirty-five “adventures” on the part of the Hidalgo. A second map, titled “A Geographical Map of the Voyages of Don Quixote and the Sites of His Adventures,” appears in the edition of 1797–1798. The insertion of maps into the narration lays stress on the latter’s plausible character. As Chartier emphasizes, “The presence … of maps that draw the imaginary wanderings of a fictional character into territories known to the reader enhances the reality effects of the writing.”15

But if the presence of maps in literary (but also cinematographic) fiction fosters the attribution of a reality to the imaginary worlds their authors conceived, it nonetheless remains to be seen how this attribution of reality is made. In other words, how does cartography make possible this passage from fiction to reality? For the sake of argument we can distinguish two configurations in which cartography intervenes in a differentiated fashion:

1. On the one hand, there are maps representing invented places, places explicitly posited as fictive. Such is the case, from Lord of the Rings to Game of Thrones, in so-called fantasy literature whose developments are constructed around a detailed mapping of imaginary territories (Middle Earth, Westeros). Yet beyond this specific genre, many writers can be considered creators of territories. Thus, even if their topographies and their forms derive from real places, the maps of Faulkner’s Yoknapatawpha, of Thomas Hardy’s Wessex, of Juan Benet’s Région, or of Michel Butor’s Bleston represent spaces their authors have invented.

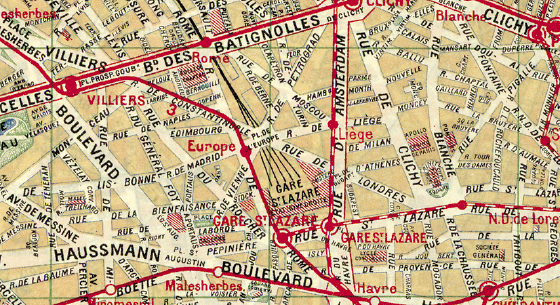

But what do these maps really display? What, it might be asked, is the referential value of these maps that represent fictive places? In this respect the map of the Island of Utopia found in the eponymous work of Thomas More (1516 and 1518) is paradigmatic of this operation that consists in representing nonexistent places as if they were real. From this perspective we can look at the later—and in fact quite mysterious—map drawn by Abraham Ortelius (circa 1595), ordered by one of his friends, Mattheus Wacker in Wackenfels (figure 1.3).

Figure 1.3. Abraham Ortelius, Utopia Typus, ex Narratione Raphaelis Hythlodæi, Descriptione D. Thomas Mori. Antwerp, 1595–1596.

It matters little if this map corresponds to a desire on the part of Ortelius, who in fact did not include it in his Parergon. In my view it is more important to dwell on the type of paradox contained in this map, a paradox that at once constitutes and reveals the inner tension that, I believe, runs through most maps that designate invented or fictive places. The island represented by this map does not exist. It is a nonplace or perhaps a place-off, yet still within the map it is depicted as a geographic reality analogous to other territories, to other islands that can be found in Ortelius’s Theatrum orbis terrarum. In other words, by dint of the map the Island of Utopia acquires a sort of effective territorial reality: yes, Utopia exists, but only on its map. Utopia does have a place, but this place is the map that represents it. Here Michel Foucault’s famous expression is applicable: the map of Utopia is a heterotopia, a sort of “counteremplacement” inside of which Utopia acquires a reality that can be grasped—that is, a reality that can be thought.16 Nonetheless the reading of the toponyms on Ortelius’s map adds a supplementary dimension to this heterotopical affirmation: the cities are named “Horsdumonde,” “Nulleville,” “Keinstadt,” the rivers are designated as “Nullipiscius,” “Senzzaqua,” “Sanspoisson,” and so on, as if it were a question not only of displaying a nonexistent reality but furthermore a reality that in itself is contradictory, a reality without being of its own because it denies itself. Put otherwise, the map shows not only a reality that is not but also a reality that cannot be. Such is the thought that the map, a cartographic heterotopia, inspires: a condition of nonbeing, the reality of a nonexistent reality, of a nonplace that is in itself contradictory but nonetheless can be thought because it is represented, drawn in the map itself, which at once displays it while demonstrating its impossibility. But what does it mean to consider the map of a reality that does not exist? Simply, it is tantamount to affirming the reality of fiction and to positing fiction as a dimension of reality.

What is the ontological tenor of these places invented by literature (and no less, by philosophy, painting, and cinema) and, at the same time, represented in geographic maps? German philosopher Hermann Schmitz used the notion of “semi-thing” or “half-thing” (Halbding) to designate these real entities that are not things (because they lack substantiality, duration, material density, morphological permanence, etc.), but that act on us as if they were things, generating sensations, feelings, pain, and so on, or generally bodily affects.17 I propose that we export the notion and apply our question to it: the fictive places that we see nowhere other than on the maps that represent them—that we follow so closely, that we trust so faithfully that our imagination gets carried away in the course of reading—become “half-places.”

2. In literature there is a second category of maps in which the “reality effect” seems even more accentuated, namely, those that represent existing places, but inside of which original fictional worlds unfold. Thus, in preparing the fourth edition of The Life and Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe (1719), Daniel Defoe uses as the frontispiece of the work a world map on which he draws the route and the place of the unfortunate hero’s shipwreck. In the same way, Jules Verne inserts in Around the World in 80 Days (1873) a world map that allows the reader to follow Phileas Fogg’s adventures. In another of Verne’s novels, Aventures de trois Russes et de trois Anglais dans l’Afrique Centrale (1872) (Meridiana: The Adventures of Three Englishmen and Three Russians in South Africa), a map juxtaposes the itinerary of the expeditions Verne describes and the one made in the same places by David Livingstone. If, generally, the literature of voyage and adventure accords an important place to cartography, then the same holds for the whodunit or mystery novel that makes abundant use of maps at the very moment, for the first time in 1868, when Émile Gaboriau, the inventor of the genre, drew a map of the crime scenes in Monsieur Lecoq.18

How can we evaluate the way cartographic representation situates real places in these works of fiction?

Nonetheless, the map is what makes possible this inscription of true urban reality into the territories of fiction. Cartography—that is, the possibility of relating the fictive universe to a real space via localization—allows the inverse, yet in the same way, of adding to real space the dimensions of fiction. The map operates transitions, passages, between the real and fiction.

By way of the map readers learn that an atmosphere of fiction floats like a cloud over the cities, and that fiction is written into the intersections where they can hope to see the characters of the novel whose steps they follow reappear and the fiction reflected in the shop fronts or street names. Basically, readers launch themselves in pursuit of a text that is distributed in space and materialized in buildings, streets, public places, but also in names. A real city is transformed into a space of fiction by virtue of the intrinsic power of displacement that the map transforms into a large-scale treasure hunt. Walter Benjamin compares Paris to the great reading room of a library through which flows the Seine: “With Notre-Dame we think of Victor Hugo’s novel. The Eiffel Tower—Cocteau’s The Wedding Party on the Eiffel Tower. … The Opera: with Leroux’s famous whodunit ‘The Phantom of the Opera’ we find ourselves in the lower depths of the edifice and, too, of literature.”20 The map reveals an imaginary, a floating, secondary, often invisible geography. Cartography awakens the immediate fictions that are asleep on the sidewalks and at the doorsteps of houses. If there is a dream in the living body of cities, cartography is what indicates the way to enter and how to find one’s bearings.

Thus the operations of the map move simultaneously in two opposite but complementary directions: by means of localization the map makes it possible to anchor fiction in the real, but in the same way it makes possible the introduction of a fictionalizing dimension in the real. It is not only fiction that is bound to a spatial reality, but also geographic space itself that is opened from the inside onto the possibility of fiction, as if fiction were one of its dimensions and yet again one of its still-unexplored resources. The maps that transcribe the multiple trajectories, indeed the errant travels of fictional characters are at the same time operators that transform real space into a space of possible fictions.

If space plays a decisive role in the development of fiction, then cartography occupies a strategic place. Maps have at least four functions in the general economy of a work, and especially in the process of writing and in the construction of the narration: (1) the map can function as an element setting the fiction into motion; (2) it allows a frame to be drawn around the plot, or it can place the intrigue within the perimeters of a theatrical stage; (3) it can become a rule or a principle for the ordering of narrative sequences; (4) finally, cartography constitutes a recourse or even a resource allowing the writer to be free of the linearity of a story or, in any case, to call the linearity into question.

On one of these occasions, I made the map of an island; it was elaborately and (I thought) beautifully coloured; the shape of it took my fancy beyond expression; it contained harbours that pleased me like sonnets; and with the unconsciousness of the predestined, I ticketed my performance ‘Treasure Island.’ … Somewhat in this way, as I paused upon my map of ‘Treasure Island,’ the future characters of the book began to appear there visibly among imaginary woods; and their brown faces and bright weapons peeped out upon me from unexpected quarters, as they passed to and fro, fighting and hunting treasure, on these few square inches of a flat projection.21

In this case, the map is not only a reader’s guide but also, containing a kind of creative power, it becomes an element that gets the story moving—in other words, it serves as a stimulus to the imagination of the writer who contemplates it. Here the image is not a simple illustration of the tale, but of its generative components.

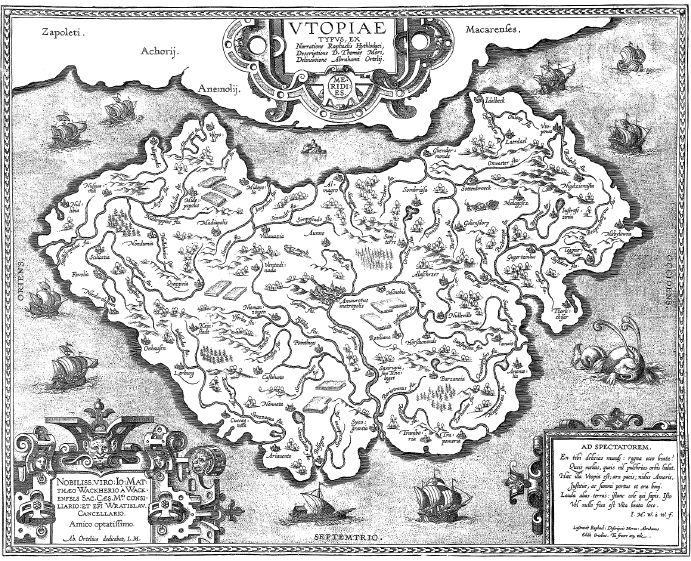

For Émile Zola, in constructing the Rougon-Macquart series, what Stevenson presents as a fortuitous discovery becomes a methodical practice. His Carnets d’enquête: Une ethnographie inédite de la France (Notebooks of Inquiry: An Unedited Ethnography of France) reveal that Zola habitually drew sketches of the terrain in which he tried to characterize an architectural motif or an urban place, the characterizations reflected in his works.22 In the same way, genetic analysis of the writings has often emphasized the role that visual—and notably spatial—images play in the development of Zola’s novels.23 Thus, in L’Ébauche de Germinal Olivier Lumbroso underscores the latent presence of geometric figures, of the square and the crossing of diagonals, in the structuring of the narrative topology. But Zola also draws a map of the region of Marchiennes (figure 1.4) that serves in a way as an experimental space in which he can put the story to work.

Figure 1.4. Émile Zola, manuscript draft of Germinal. Bibliothèque Nationale de France, folio 109 (call number: NAF 10308)

The map and the geometric figures, much like the sketches in the Carnets d’enquête (that furthermore interact with one another), belong to the narration’s generative schemata. As Lumbroso has noted, they are a “springboard for the imagination: at once a miniature stage, a chessboard, a territory or a theater of operations, progressively inhabited and changed by the characters, by the scenarios and the values that the novelist invents in the course of preparatory work. The drawing becomes animated, and this animation comprises a fundamental process of the creation, indeed an initial drafting of the writing of the novel.”24

2. The preparatory dossiers of the Rougon-Macquart contain many manuscript maps that allow Zola to establish the general geographic frame in which the plots of the novels will develop—for example, the map of the region of Plassans at the beginning of the detailed view of La Fortune des Rougon (1871), the map of Paradou in La Faute de l’abbé Mouret (1875), the summary map of Alsace in La Débâcle (1892), and so on. They allow the writer (the first reader of the work?) “to visualize and to get to know,” as Stevenson noted, “his countryside, whether real or imaginary, like his hand.”25

Yet, as Lumbroso notes, the novelistic maps chart a space that above all must respond to the inner strictures of the fiction. Thus, in La Fortune des Rougon Zola does not hesitate to create a route to Vidaubon and Aups that does not exist in reality.26 In the same way, in the map of Alsace positions and distances are slightly altered to correspond to Zola’s narrative intentions.27 In Germinal, Zola inscribes the real geography of the region around Marchiennes (the city, the mineshaft) inside a social and symbolic geography (the miners and the placeholders, with the director between them). Put otherwise, if maps allow the author of the novel to construct and visualize space, they correspond more to narrative topologies than, in a strict sense, to topographic representations.

3. It is in this sense that maps can be considered with respect to the role they play in the organization of the story, in the structuring of the plot. The case of Joyce’s Ulysses is exemplary. In no other novel is the role of topography and cartography as implicated in the conception and organization of the work. Joyce makes use of a map when he writes Ulysses—perhaps the Ordnance Survey Map of Dublin—and he uses it to construct the story.28 “Joyce wrote the ‘Wandering Rocks,’” writes Frank Budgen, “with a map of Dublin before him on which were traced in red ink the paths of the Earl of Dudley and Father Conmee. He calculated to a minute the time necessary for his characters to cover a given distance of the city.”29 In this example (but many others can be found) the action of the novel is not only deployed in but also according to the space of the map. There is a certain interaction between the spatial distribution of the places on the map and the succession of episodes that structure the story. The progression of the narration melds with the sum of the travels on the part of the characters between the places represented on the map, according to the paths drawn on it and the space of their measured time. The reader witnesses a double operation, at once one of a “spatialization of writing” and, as in Joyce, that of a “staging of the plot in space.” The map is the site of this double operation.

4. But in certain cases cartography can become a mechanism of conflict, even of shattering, of the typical organization of narration. It is the principle (or secret model) of a spatialized writing, or in any case of a fiction that attempts to free the story of a linear temporality for the sake of what might be called a “dissemination” of meaning and of a multiplication of narrative units. The cartographic paradigm, and this whether a map is actually drawn or not, makes possible the simultaneity of several narrative trajectories, the dispersion and dislocation of the point of view, or the parallel montage of several stories—in other words, a spatialization of the story or at the least a spatial ordering of its components. When Thomas Mann described to Theodor Adorno the “principle of montage” that he used in his Doctor Faustus, on his own account he adopts a method analogous to that which had generally been used in literature written between the First and Second World Wars, in, for example, Döblin or Dos Passos.30

The analysis that Walter Benjamin proposes for Döblin’s Berlin Alexanderplatz might be extended to certain forms of cartography: “The stylistic principle of this book is montage. In this piece of writing there is a cavalcade of petty-bourgeois writings, scandalous stories, news items of accidents, sensational events of 1928, popular songs, short announcements. The montage shatters the ‘novel’ both from its structural and stylistic points of view, thus creating new epic possibilities, notably in the formal design.”31 The map can be considered a writing mechanism of the same genre, allowing the novels to assemble, collate, bring forward, and set back stories and images of every kind. The map does not moreover lead inevitably to the dispersion and dislocation of the various meanings but rather to the consciousness of their complex tessellation within a work constructed spatially.

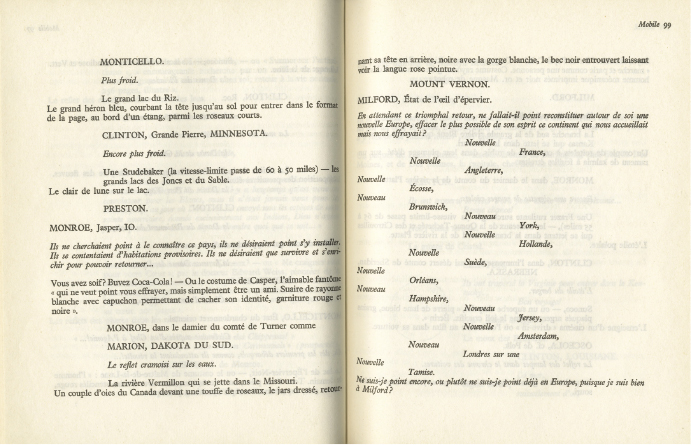

Therein cartography bears a form of literary rationality that can be called a mode of thinking with space and a thinking of writing with montage. In Mobile (1962) Michel Butor, like Georges Perec in La vie mode d’emploi (1978), made it manifest: the map and the atlas are modalities or possibilities of writing and of creation (figure 1.5).

Figure 1.5. Michel Butor, Mobile (Paris: Éditions Gallimard, 1962)

The writer becomes a cartographer, both of which are taken up with the description and creation of a space that is fundamentally a space made of words and lines. Which Georges Perec underscores: “Space thus begins, only with words, signs traced on the white page. To describe space: to name it, to draw it, much as the artists of the portolan charts that saturated the coastlines with the names of ports, the names of capes, the names of creeks until a continuous ribbon of text separates the land from the sea.”32

At the beginning of his “Berlin Chronicle,” having imagined the possibility of a “biocartography” or a biographical cartography, Walter Benjamin writes:

For a long time, for years I confess, I have been caressing the idea of graphically organizing on a map the space of life—bios. First off, I was vaguely dreaming of a Pharus plan but today I would be more inclined to return, if there existed one for inner cities, to the état-major map. … I imagined a system of conventional signs and on the grey background of these maps there would be visible in every color the lodging of my friends, men and women, of the meeting places of diverse collectives …, the hotel rooms and the whorehouses in which I stayed overnight, the decisive benches of the Tiergarten, the paths to the school and the tombs I saw being filled, the places where cafés held a place of honor whose names today have disappeared and that had always been on my lips, the tennis courts where today are empty rowhouses and rooms decorated with gilt and stucco, where the fears that came with dancing lessons were almost the equal of gymnasiums, if all that could be distinctly drawn.33

Extending Benjamin’s intuition, we can wonder what a cartographic writing would be, or a cartographic moment of writing, indeed a carto-graphy. In other words, what does cartography teach and bring to writing? We can also ask if cartography itself, insofar as it would be conceived not only as a means of representing the territories to which it refers, but also as a form or mechanism of writing, has the power to shape information, ideas, and values. It is this organizational and configurative power of cartography that needs to be studied. As we have seen with Zola, when the map is deployed in the novel it becomes a formal operator that allows the articulation of a real topography with a sum of fictional intentions. It can surely present a documentary aspect that embellishes the construction of the novel, but in itself it is subordinate to the project of the novel. In the literary story, the map carries meaning only consequently as a blueprint of a space-for-the-story: it represents the space-of-the-story. But to say that the map represents the space of a narrative topology makes it possible to indicate the veritable stake of its presence in the novel: the question is not that of the opposition between the “real” and “fiction,” but rather that of the project of the fiction itself and of the graphic means it mobilizes so as to be shown and developed. In other words, where cartography is in question, the configuration of a space of reference pertaining to the unfolding of the narrative scheme is the very crux of the fiction.

Translated by Tom Conley