GEORGE RICHARDSON’S CAREER AND THE LITERATURE OF ECONOMICS

INTRODUCTION

George Richardson’s academic career is full of the kinds of achievements of which most academics can merely dream. His entry in International Who’s Who reveals that, after teaching economics as a fellow of St John’s College, Oxford, from 1951, he was promoted in 1969 to University Reader in Economics, a post he held until 1973. Between 1974 and 1988 he was Chief Executive of Oxford University Press and from 1989 until his retirement he was Warden of Keble College, Oxford. His expertise as an industrial economist was recognised in his appointments as a member of the Monopolies Commission and as a Member of the Economic Development Committee for the Electrical Engineering Industry. He was also a member of the Royal Commission on Environmental Pollution (1973–4). His citation record, discussed later in this paper, shows his work to have been used by scholars in many countries and many disciplines. Yet, despite this, the impact of his work has been far smaller than he might justifiably have expected and, indeed, he records his disappointment in his introduction to the second edition of Information and Investment (1990: xvii). Interest in his work is growing, but his contributions remain unused by most economists and unknown to their students. This chapter is an attempt to clarify and explain the place of Richardson’s writings within the literature of economics. It has something of a reflexive dimension, for George Richardson’s contributions to economics are helpful for making sense of coordination problems and processes in the market for scholarly ideas.

The chapter extends some of the ideas that I first outlined over a decade ago in a paper on the behaviour of economists (Earl 1983a). In that paper I considered the roles that career aspirations and academic search processes play in shaping the kinds of works that economists prefer to produce and whether particular contributions to economics are accorded high status or are marginalised. Richardson’s contributions were grouped with those of P. W. S. Andrews, Jack Downie and Edith Penrose as being of a modern-day Marshallian variety, whose neglect by the mainstream of the economics profession is on a par with that accorded to the Carnegie–Mellon behaviouralists Richard Cyert, James March and Herbert Simon. In recent years key contributions from all of these deviant scholars (with the exception of Downie) have been reprinted in new editions. This must be very gratifying for those deviants such as Richardson who, unlike Andrews and Downie, have lived long enough to see a belated growth of interest in their work. Even so, the fates of their contributions continue to call into question the dynamic efficiency of markets for economic ideas, challenging the sanguine views of Stigler (1982).

The rest of the chapter is divided into five main sections, followed by a brief conclusion and a lengthy appendix listing citations of Richardson’s work in scholarly journals. In the first section I provide an account of Richardson’s path into economics and his method of operating as a scholar; this turns out to be significant in terms of shaping his outputs and their marketability. Second, I examine the research co-ordination problem: the need for scholars to ensure that they are not engaged in mere reinvention or simultaneous invention of ideas. Third, I present citations evidence of the patchy impact of Richardson’s work. Fourth, I examine critically Loasby’s (1989) claims about the role of unfortunate timing in the initial reception of Information and Investment. Finally, I consider the role of networks as key determinants of the fates of contributions to knowledge.

RICHARDSON’S PATH TO ECONOMICS

Richardson’s early career is both intriguing and paradoxical in relation to his contribution to economics. Since he was born in 1924, his university education was affected by the Second World War, as were his initial periods of employment. During the 1940s he completed a pair of two-year degrees, following each with periods of government service. His education could very easily have led him to become a physical scientist rather than an economist, for in 1942 he commenced studies at Aberdeen University and read mathematics and physics. This left him far better equipped in mathematical terms than most of his fellow economics students when he took up a scholarship to Oxford in 1947 and switched from science to Philosophy, Politics and Economics (PPE). At Oxford, his economics papers were in Economic Organisation, Economic Principles, Economic Theory and Statistics. Though the Oxford BPhil in PPE had been newly established in 1946, Oxford teaching was for the most part conservative rather than contemporary in its coverage (Young and Lee 1993: 167). However, this was the period in which Hicks was very much in the ascendant at Oxford, and in 1952 Hicks was ranked ahead of both Robbins and Harrod for the Drummond Chair of Political Economy. By that time Hicks had became Richardson’s mentor.

It was Richardson’s mathematical training that led to his links with Hicks. His regular tutor in economics was Neville Ward-Perkins, an economic historian who had been taught by Andrews. When Richardson came to take the theory paper, Ward-Perkins initially arranged for him to be tutored by Frank Burchardt. However, after Richardson showed off his mathematical skills in presenting a paper on Keynes’s theory of employment, Burchardt asked Hicks to tutor Richardson instead. This rather immature display of mathematical prowess is recalled by Richardson with some shame – one of his classmates remarking on leaving the seminar that if this was economics, then he wanted none of it – but he notes that without it he would not have become an economist. The irony, of course, is that much of what he was subsequently to write points away from analysing economic problems with the aid of mathematics and leads instead to a recognition of the need to become familiar with institutional details of devices that firms use to assist co-ordination.

Richardson’s publications nevertheless have a distinctly Hicksian look to them: despite the paucity of diagrams and the absence of mathematical notation, Richardson’s Information and Investment closely resembles Hicks’s (1939) Value and Capital (Hicks 1945), with its absence of section headings and only the use of occasional footnote references, mainly to classic writings. Unlike today’s scholars, who sometimes err in the direction of citation overkill when setting their works in the context of existing literature, Richardson and his mentor wrote about theoretical issues as if applying logic in their armchairs. Richardson’s experience of being taught by Hicks was conducive to this, for the latter’s method involved getting his students to read the work of great figures such as Marshall, Menger and Walras rather than mastering a list of recent articles. Unlike Andrews, who followed in Marshall’s approach of writing from a firm base in practical knowledge of business, Richardson’s scholarship was driven by curiosity and an eye for (what seemed to him to be) ‘the obvious’; it involved much time thinking about problems in his college room or whilst walking round the college garden. When he came to write Information and Investment, Hicks read the book in draft but provided few comments and did not discuss its central themes.

Though Hicks seemed rather distant from Richardson’s own contributions, apparently regarding him as having focused too narrowly, too soon (so Richardson discovered after Hicks had died), he did much to help Richardson to get started as an academic. He was initially unsuccessful in convincing Richardson to stay in academic economics rather than pursue a diplomatic career but a year later, when Richardson had second thoughts and wrote to his mentor, Hicks managed to secure him a doctoral studentship at Nuffield College. Richardson was not particularly enamoured with his initial DPhil thesis research under Hicks and was thus happy to abandon it after only two terms, when he obtained a Fellowship at St John’s on the basis of the promise he had shown. (The Senior Tutor at St John’s advised him that it was no longer appropriate to read for a doctorate!) The ease with which Richardson got established at Oxford in the early 1950s is to be contrasted with the difficulties that Andrews had in retaining his Fellowship at Nuffield College in 1953: Hicks actively sought to prevent this, having a very low opinion of Andrews’s capabilities as an economist (Lee 1993: 22).

Differences between Richardson and Andrews in terms of background and relations with Hicks are perhaps significant in helping us to understand why they had almost no discussion together despite feeling they had something in common in doctrinal terms: in the 1950s Richardson would have seemed an abstract theorist to Andrews, who had become suspicious of theoreticians and was immersing himself in empirical studies. The latter’s uneasiness in the company of theoreticians at least meant that there was little danger of links developing between these two post-Marshallians that could harm Richardson’s standing in the eyes of those in positions of influence. Even so, having been introduced to full cost pricing as an Oxford undergraduate, Richardson did take from Andrews the idea that spare capacity facilitates the avoidance of co-ordination problems since it permits firms to satisfy new demand without losing the goodwill of regular customers (Richardson 1960: 127).

During the 1960s Richardson’s style of research increasingly came to resemble Andrews’s post Marshallian/behavioural mode. He became involved with applied studies, beginning with the heavy electrical plant industry, which led to his membership of the Monopolies Commission and provided the knowledge that eventually inspired his most influential work – his (1972) article ‘The organisation of industry’. This change of research style arose by chance but built on insights from his armchair theorising: at a dinner in Sidney Sussex College he happened to sit next to Sebastian de Ferranti, an electrical engineering industrialist, who mentioned that the Restrictive Practices Court was about to consider a price agreement on transformers. Though Richardson knew nothing about the case, he immediately grasped the relevance of his work on co-ordination and remarked that there were arguments in favour of such restraints on trade, which most economists wrongly ignored (see further Richardson 1965, 1966, 1967, 1969).

To conclude this commentary on how Richardson became an economist and how he operated as a scholar, I want to suggest that Richardson’s early spells of work outside economics may have affected the contribution he made. Richardson himself reports that Information and Investment originated in a long struggle with a theoretical conundrum, his awareness of which emerged from uneasiness he felt even as an undergraduate about economists’ accounts of how equilibrium states might be achieved. A modern industrial economist presented with the Richardson Problem would tend to recognise that it can be framed in terms of the theory of games. However, Richardson’s writings about the problem of investment co-ordination do not presume that entrepreneurs place their bets without first trying to improve the information they have about the plans of others whose actions may impinge on the outcomes of their own ventures. Another way of putting this is to say that entrepreneurs seek to gather intelligence by observing what rivals are up to or by exchanging information by mingling together or deliberately sending signals. That Richardson should have come to view the mitigation of the problem in this way is hardly surprising when we note that Richardson’s spells of government service in the 1940s included intelligence work. Just before the end of the war and soon after graduating from Aberdeen, he was sent, as a temporary naval officer, to Germany for intelligence work on radar. Subsequently he was employed as a civilian at the British Army of the Rhine headquarters, on political intelligence work, and immediately after his PPE studies he went into the Foreign Service, having taken the entrance examination before taking his Oxford Finals.

THE RESEARCH CO-ORDINATION PROBLEM

Academics have to grapple on a daily basis with a co-ordination problem every bit as complex as that upon which Richardson focused in Information and Investment: rewards will go to those who succeed in staking claims to authorship of pioneering contributions valued highly by their peers, or whose contributions succeed in capturing the attention of their peers because of the way that they have been marketed, despite not being the first in which the ideas were developed. Physical scientists are not shy about debating in public their claims for primacy as discovers of particular phenomena: a recent case in point is the battle between French and American AIDS researchers over the initial discovery of HIV. Economists tend to be rather more reticent, or simply ignorant of potential for disputes, so that it is left to historians of economic thought to explore possible instances of simultaneous invention or of credit going to reinventors who, whether out of ignorance or opportunism, did not give credit where credit was due (cf. Earl 1993).

Here is a touch of irony: George Richardson’s own career as an academic illustrates well the potential for simultaneous invention of ideas and for an academic to be in the right place at the wrong time. In respect of the former we can note two examples. First, Richardson’s (1972) article on the co-ordination of complementary investment and the subtle methods for co-ordinating vertical production and distribution processes appeared around the same time as a paper on a similar theme by Blois (1972), from which the term ‘quasi-integration’ seems to have come into the language of economics and strategic management. Richardson had the greater richness of vision, but Blois had the buzz-phrase. Second, there is Richardson’s (1975) awareness that he and Kaldor (1972) were thinking on similar lines about the significance of increasing returns; he notes that ‘This paper was already in draft before the publication of Professor Kaldor’s article “The Irrelevance of Equilibrium Economics” in the Economic Journal … and I did not try to adapt it to take account of what he said. The arguments I put forward here are similar in important respects to those of Professor Kaldor’ (Richardson 1975: 351). Like Kaldor, he acknowledged the significance of Allyn Young’s (1928) ‘justly celebrated article’ as a source of inspiration (Richardson 1975: 352). To date, Kaldor’s paper has attracted much more attention, probably due to its location in a core journal and Kaldor’s fame, but the profession would benefit from being familiar with Richardson’s paper too, and from seeking to pull together links between the different points of focus of the two contributions: unlike Richardson, Kaldor has nothing to say on the relationship between specialisation and diversification in the growth strategies of firms. Both works deserve to receive more attention from those who work in the emerging literature on strategic international trade theory.

In respect of the question of primacy, we should note that, although the profession at large may ultimately follow Brian Loasby and myself (Earl 1983a), and label the investment co-ordination problem in his honour as the Richardson Problem, he was by no means the first to recognise it. Nor was Richardson the first to write about the potentially beneficial role of market ‘imperfections’. For example, discussions of interlinked expectations and the importance of frictions for the practical workings of the competitive system are to be found in the work of Clark (1923: 417, 460) and Dobb (1937: 206–7), though in relation to the process by which prices are changed. More noteworthy is a neglected article by Williams which is concerned with the economics of structural change: its main theme is that ‘dynamic competition cannot be “perfect”’ (1949: 124). The closeness of Williams’s thinking to that of Richardson may be gauged from the following extracts:

The fact that there are fixed factors means that capital losses inevitably follow a change in demand. Furthermore, these fixed factors, or frictions, are a pre-condition of the operation of the pricing mechanism. For if there were perfect mobility the emergence of a difference between price and cost in one sector would cause such a flood of resources there as to ensure losses for all. Nor could the flow back to the now prosperous deserted sectors be orderly, for with static expectations and perfect mobility (which implies that no producer has a preference or special competence for one industry rather than another) there would be nothing within the price mechanism as such to make it possible for producers to choose a profitable transfer.

… he cannot rely on the law of large numbers to bring it about that too many firms will not go to one industry or another, for it is likely that industries will have need for widely varying numbers of firms.

(Williams 1949: 126 and footnote)

The avoidance of such a breakdown of the pricing mechanism is due to lack of mobility, and to firms having, at any one point of time, differing degrees of mobility.

(Williams 1949: 127)

The difficulty of co-ordinating structural change and cyclical demand patterns was also considered by Joan Robinson (1954), but she did not raise the possibility that less than perfect flexibility of response might be a desirable feature. That she did not do so is perhaps surprising given both her closeness to Keynes and the latter’s (1936: 239, 269) macro-level realisation that stickiness in the wage unit was essential to provide an anchor for the price level because in the event of a shortfall in or excess of effective demand changes in money wages would not necessarily change the level of real effective demand and hence the demand for labour. The greater overall farsightedness of Williams’s paper obviously includes the role he assigned in passing to special competences as limiting the industries in which firms will wish to participate: this theme not only resurfaces in Richardson’s work (including his 1975 paper) but is also, of course, central to recent work on the resource-based view of the firm that takes its lead from Penrose (1959).

Though scholars such as Williams and Robinson came to see the essence of the Richardson Problem before Richardson did, the case for naming it after him is that they focused on it briefly, without also highlighting complementary investment as a problem area and without his subtle appreciation of what might be included on the list of beneficial imperfections.

THE LIMITED IMPACT OF RICHARDSON’S WORK

Economists who read Loasby (1989) or my (Earl 1983a) paper on economists’ behaviour may infer from comments therein about the neglect of Richardson that his publications were almost completely ignored. This inference would be somewhat mistaken but would certainly be correct in respect of research and teaching in the core microeconomic theory area of the discipline. His work challenged the wisdom expressed in the textbooks that were available as he developed his thinking, and it provided a basis for studying economics as a co-ordination problem, with a novel focus on institutional arrangements that facilitate co-ordination. But after three decades it had not become incorporated into standard textbooks.

Richardson’s own textbook Economic Theory (1964a) was commissioned by Roy Harrod, general editor of the Huchinson University Library economics series, shortly after the publication of Information and Investment. It was hardly the ideal package to become a standard tool in a revamped economics paradigm. It began, like its rivals, with the logic of choice, Richardson’s strategy being a very Hayekian one of going on to show that the dispersion of knowledge made it necessary to have decentralised decision-making. Unfortunately, it was too dense for the typical student and lacked the more lavish attention to matters of layout that was beginning to characterise the bloated conventional texts at the time it appeared; it was a book of intricate continuous argument in the style of the introductory philosophy texts by Russell and G. E. Moore that Richardson had himself enjoyed and was not at all the type of work to appeal to those with short attention spans.

Richardson’s textbook was not a complete sales disaster, despite not taking off into multiple editions, and was translated into Spanish and Portuguese. Between it and my recent treatment (Earl 1995: ch. 10), the only textbook on microeconomics to offer a taste of Richardson’s perspective was the readings collection by Wagner and Baltazzis (1973) which reprinted his (1971) article ‘Planning versus competition’. Given that this article first appeared in Soviet Studies and given also the recent interest in the relevance of Richardson’s work for countries undergoing the transition from communism to more market-based methods of economic organisation, it is interesting to note that at the time of the Prague Spring he was approached by an economist from Bratislava, Madame Sestokova, about the possibility of translating Economic Theory into Slovak. The book was seen in what was then Czechoslovakia as addressing the problem of how to move towards decentralised decision-making. Madame Sestokova visited Richardson in Oxford and, a few weeks before the Russian invasion, Richardson visited Prague and Bratislava. With Dubcek out of power it seemed to Richardson unwise to write to those who had warmly hosted his visit to Czechoslovakia – letters from the West might put their positions in jeopardy. After the fall of communism, Richardson did try to resume contact and was greatly saddened to discover that Madame Sestokova and her family had fared badly in the interim and that she was seriously ill in hospital.

Though the central ideas in George Richardson’s work imply the need for a major reworking of textbooks, they are not fundamentally difficult to grasp. He expressed them in plain English and, particularly in his post-Economic Theory work, with plenty of memorable real-world examples. My experience over many years is that students find Richardson’s ideas easy to assimilate compared with many of the concepts of neoclassical theory: a teacher who wishes to inspire an intermediate microeconomics class will find it far easier to do so by beginning with the economics of information and coordination than with the axioms of mainstream choice theory.

To see his ideas being discussed in textbooks it is generally necessary to move from the core of economics, which any student will cover, to industrial economics and business strategy. There, Richardson might have more of a feeling of success, but still considerable grounds for feeling that the profession has not made as much of his work as it might have done. The most widely read discussion of the entry co-ordination problem is doubtless the chapter on capacity expansion decisions in the bestseller by Porter (1980), but Porter seems engaged in reinvention, for he makes no reference to Richardson as he examines the problem and considers various pre-emptive signalling approaches for dealing with it. Richardson’s vision of the significance of corporate capabilities and relational contracting is going to be absorbed by many managers via John Kay’s strong-selling Foundations of Corporate Success, which refers to Richardson (1972) very briefly as ‘an early contribution’ (Kay 1993: 85), in a guide to the literature; Richardson’s way of thinking will thus spread but probably without his name attached to it and with Kay’s readers being oblivious of his personal links with Richardson.

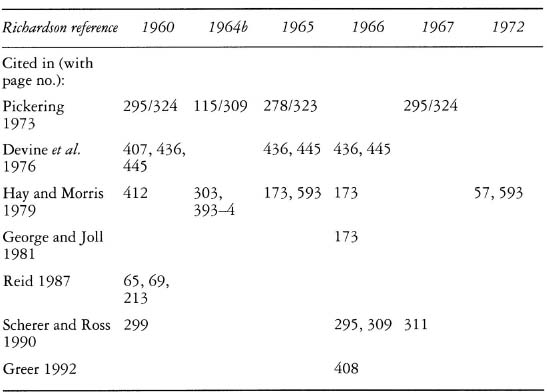

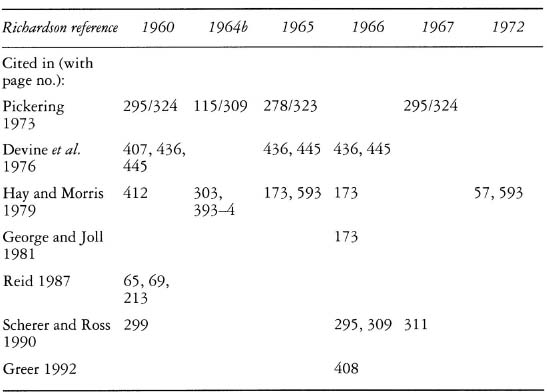

It would certainly be incorrect to say that Richardson is ignored in industrial economics. He is cited in the leading British undergraduate-level texts, and occasionally in American ones, though generally without his contributions being made central to the analysis – there is a big difference between being merely footnoted and being discussed at length (as in Earl 1995) as an important contributor whose focus can be summed up as the Richardson Problem. (At present, anyone who uses this shorthand term with students has to be careful to remind them of its limited currency.) Table 2.1 shows the extent to which Richardson’s contributions are discussed or noted in some of the widely used texts.

If economists were as well informed as their hypothetical decision-makers it would be natural to expect to see Richardson’s work on co-ordination receiving more attention as industrial economics texts at the advanced level have become dominated by an interest in game theory, but it is not mentioned in the market-leading texts by Tirole (1988) and Martin (1993). Though Richardson had originally wanted to call his 1960 book The Economics of Imperfect Knowledge, anyone who hopes to see his ideas being discussed in Phlips’s The Economics of Imperfect Information (1988) will be disappointed. One might even be so bold as to suggest that the more industrial economics texts incorporate modern microeconomic theory focused on incomplete information, the less likelihood there is of Richardson receiving attention. Even so, there are still some occasions on which Richardson is cited in modern survey discussions at exactly the point where he might expect to be: for example, Information and Investment is cited in R. J. Gilbert’s chapter on mobility barriers in the Handbook of Industrial Organization (Schmalensee and Willig 1989: 534) and ‘The organisation of industry’ is quoted by Steve Davies in his chapter on vertical integration in The Economics of the Firm (Clarke and McGuinness 1987: 84). To some extent, then, Richardson’s ideas have been received into the normal science textbooks of industrial economics, but they certainly have not had a revolutionary impact on the hard core of this subdiscipline. However, to the extent that modern advanced-level texts are concentrating on surveying recent contributions to the field, it is somewhat surprising that Richardson receives attention at all in these works.

Table 2.1 Citations of Richardson’s work in widely used industrial economics texts

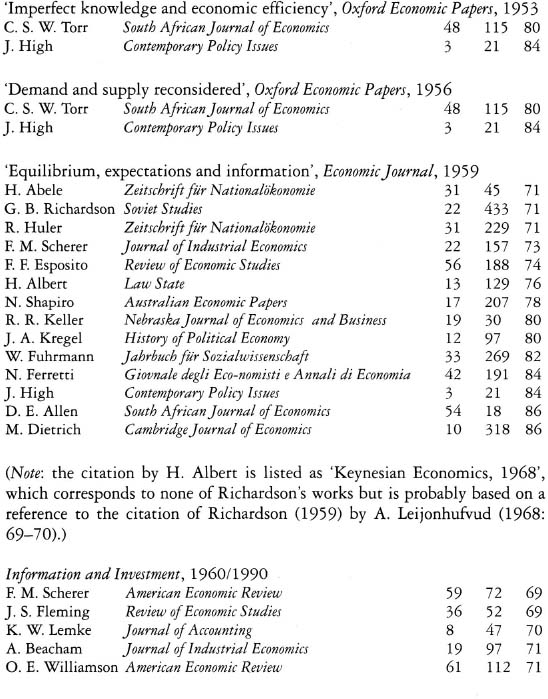

Whereas a Kuhnian historian of science would look to textbooks for evidence of a scholar’s revolutionary impact, present-day academic audits of research productivity focus on success in being published in ‘core’ journals, on the basis that it is much more difficult to have works accepted in these journals and that articles published in them are likely to be cited in subsequent work. All of Richardson’s English-language articles were in high-ranking journals but that did not guarantee that they would be rapidly picked up and frequently cited. It is somewhat difficult to study the citation pattern of Richardson’s work before 1969, for it was not until that year that the Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI) commenced publication in its present form. In the Appendix to this chapter is a complete listing of citations of Richardson’s works recorded in the first quarter-century of the SSCI. Richardson is cited around seven times per year, on average, 186 times in all (including only two self-citations), with the lion’s share of the citations being Information and Investment (fifty times) and ‘The organisation of industry’ (eighty-three times). The SSCI listings provide a fascinating picture of how his work has been used.

Richardson has been cited in most major economics journals and by many eminent economists, including Nelson, Scherer, Scitovsky, Teece and Williamson, but these ‘core’ citations, most of which are of Information and Investment, account for only a small fraction of the total. Many citations are not in English-language journals or are in journals outside economics, in disciplines such as marketing, strategic management, geography and sociology. This is particularly the case with his 1972 paper. Richardson’s work is not yet famous in the sense that most teachers and students of economics have heard of it, but that has not prevented it from being discovered and used by scholars working outside the core of economics. So far, I have only been able briefly to examine the lists of works cited by some of the articles that cite Richardson and which I had not previously seen. The initial impression is that these papers tend to cite not only Richardson but also relatively underused works by other scholars such as Malmgren and Hirschman that I stumbled across myself in the late 1970s when first searching for contributions that might augment the Richardson perspective. But there were many works listed with intriguing titles that were unfamiliar to me. A major reason for appending the SSCI listings is to encourage readers to explore these works further and develop a clearer picture of the extent of thinking by other neglected authors, completing the augmentation process.

WAS DEBREU THE CAUSE OF INFORMATION AND INVESTMENT’S FAILURE TO TAKE OFF IN THE 1960s?

It seems worthwhile, as a source of lessons to academic economists writing today and wondering how their work will fare with its intended audience, to examine likely reasons for Richardson’s failure so far to have a major impact on the core of economics despite being surprisingly successful in being noticed in an interdisciplinary sense. According to Loasby (1989: 99), Richardson’s great misfortune was that his critique of general equilibrium analysis appeared just after Debreu’s exposition of an abstract economic model in which complete contingent claims markets ‘solved’ the co-ordination problem, for Richardson’s prose lacked the hard scientific appeal of Debreu’s mathematics. This view can be challenged.

For Loasby’s view to be correct, it would seem to require that economists in the early 1960s were actually worried about the co-ordination problem, and that Debreu was indeed praised for his solution to the problem around the time that Richardson’s work appeared. This being so, mainstream scholars would have no need to search for alternative perspectives that might remove their uneasiness. Contemporary reactions to both Debreu and Richardson provide evidence to the contrary and may indicate how the profession at large has tended to construe particular contributions and choose between theories. Before we consider the content of the reviews it is worth noting that book reviews in professional journals can be seen as the academic equivalent of quality signalling devices in other markets, such as reports of restaurants in good food guides, credit ratings by agencies such as Standard and Poor’s, and admission to trade association membership – in other words, they are devices of the kind that Richardson has sought to emphasise in his work on co-ordination.

Debreu’s book was not widely reviewed beyond the American journals. There were no reviews in Economica, the Economic Journal or the Economic Record, while the review in Econometrica is in quite difficult French and so would have been relatively insignificant in the English-speaking world. In the four reviews that I have unearthed Debreu was generally praised for his innovative technical exposition but the reviewers did not appear to be cheering him for showing how general equilibrium and uncertainty could be made compatible. On the contrary: either the issue was not highlighted or he came in for criticism for his abstractions and failure to use examples. In the American Economic Review Hurwicz correctly predicted that the book would have a major long-term impact but commented that, in relation to Debreu’s fifth and sixth chapters (on existence and optimality of competitive equilibria, respectively), ‘One’s understanding of the problem would have been greatly deepened by examples lacking equilibrium due to the failure of one or another of the assumptions’ (Hurwicz 1961: 416). Hurwicz had little to say, however, about Debreu’s treatment of uncertainty, merely mentioning that this was introduced in the seventh chapter. Harrell hardly went further, simply ending his purely descriptive review in the Southern Economic Journal by saying that ‘In the last chapter a revised definition of a commodity leads to a theory of uncertainty which is normally identical with the previously elaborated theory of certainty’ (1960: 150). Much more critical is Baudier (1961), in Econometrica, who noted that the cost of Debreu’s concern to state his purpose precisely is that he gives readers no indications of implications of the theory about which they must themselves form judgements. Baudier then commented that:

The consequences are, however, to my way of thinking, too important to pass by in silence and too numerous to be counted. Let’s mention this one: the last chapter introduces the possibility of ‘commodities’ of a new type for which there is no market (at least in general) and therefore the prices of those ‘commodities’ could not be held as given by economic agents who don’t even know them. Thus one of the conditions of applying the theory of equilibrium to the real world collapses.

(Baudier 1961: 259–60; my translation, with assistance from Pascal Tremblay)

Similarly, in the Journal of Political Economy the young Frank Hahn (1961) praised the Theory of Value as a technical achievement but criticised it for proceeding implicitly as if the non-existence of contingent commodity markets does not matter; for leaving no role for money; and for having nothing to say about what happens in an economy when conditions are insufficient to produce an equilibrium. That Hahn should have reacted in this way is ironic given his later spirited defences of the Arrow–Debreu approach as a benchmarking tool for policy diagnosis – arguments that Richardson (1990: xxi–xxii) finds utterly unacceptable.

None of the reviewers of the first edition of Information and Investment made any reference to Debreu’s contribution, and none noted another point that would be obvious to modern-day economists, namely that Richardson might have done well to relate his work to the literature that, by the late 1950s, had appeared on the theory of games: Morgenstern, one of the co-founders of game theory, recognised as long ago as 1928 that the attainment of economic equilibrium could not be explained in terms of existing theory in cases where an agent’s choice of a plan of action required knowledge of plans of other agents (see Borch 1973: 67). Rather, the reviewers focused on the overly theoretical nature of the book. In other words, Richardson’s marketing problem seemed to be one of getting economists to agree that there was actually a problem of co-ordination worth worrying about. It seems unlikely that, in 1960, he would have better satisfied his reviewers if he had made the most of his mathematical training and set out the co-ordination problem in Debreu’s style. His reviewers appear merely to have wanted the kinds of down-to-earth examples that he was to use so effectively in his later writings.

Potential readers of the book can hardly have been encouraged by the observation by Power in an otherwise perceptive and favourable review in the American Economic Review that:

The method of the book is essentially armchair reasoning with only occasional reference to empirical studies. … Readers may find the concluding section of the volume disappointing in the light of earlier bold statements about the omissions of conventional theory.

(Power 1961: 761)

The first comment is an accurate characterisation of how Richardson had worked, but the second is somewhat unfair: its intended implication seems to be that the book does not offer much to fill the gap that it exposes.

Lesley Cook begins her Economic Journal review by suggesting that the title Information and Investment is ‘slightly misleading’ and that the book is a ‘theoretical examination of the effects on investment of uncertainty resulting from inadequate information’ (Cook 1964: 168). The book is surely better characterised as a critique of conventional theories of the workings of the price mechanism and an alternative analysis of how allocation mechanisms work in the face of incomplete knowledge; however, Richardson may well have been wiser than his publisher in wanting to call the book The Economics of Imperfect Knowledge. (Hicks, as one of the Delegates of Oxford University Press, had been unwilling to accept that title, remarking to Richardson that it would demonstrate an imperfect knowledge of economics.) While also broadly favourable, Cook’s review can only have damaged the book’s impact by suggesting that ‘He is largely concerned with problems related to the cobweb theorem’ (Cook 1964: 168). Conventional theorists seem to be predisposed to view the cobweb theorem as affecting only agriculture and the construction industries. Thus, they would have been inclined to agree with Cook when she argued that Richardson was probably exaggerating the importance of the co-ordination problem when he applied it to investment decisions in general. (Such an inclination would have been particularly likely if they had just read Muth’s (1961: 330–4) now-famous work on rational expectations, which highlights the empirical limitations of cobweb models and tentatively argues that the rational expectations hypothesis has superior predictive capabilities – even though Richardson (1959: 233) had already called into question any notion of rational expectations.) The fact that Richardson’s book was four years old before this review appeared could hardly have helped its chances with, particularly, British economists who had not noticed it on its publication if they had in the meantime tuned into the message of Debreu. (I could find no review of it in Economica, merely one by Laurence Harris (1965) of Richardson’s (1964a) textbook. Harris does note Richardson’s focus on the restrictive nature of the perfect knowledge assumption but gives no clue to the problem Richardson has in mind; instead he goes on to criticise the text for being too brief and superficial and for lacking any discussion of method or suggestions for further readings.)

Cook argued that an orderly process of market adjustment through sequential market entry would have seemed much more plausible, especially if he had chosen to analyse the problem in disequilibrium terms rather than with comparative statics. In fact, Richardson (1960: 51–2) had presented an examination of sequential entry but noted difficulties for entrepreneurs in assessing precisely how much capacity rivals had already commissioned, the more so the larger the number of firms participating in the market. Cook further failed to explain to potential readers that Richardson’s aim was not to demonstrate, as Joan Robinson wished to do, that the co-ordination problems cause chaos and ‘the impossibility of profits’ (Robinson 1954); rather, he was more concerned to show how such problems may be avoided in practice and thereby to put readers in a better position to appraise the implications of competition policies based on conventional theories which neglect the information structures that help markets to function.

The reception given for Australian audiences by John Grant in the Economic Record echoes the sentiments of both Power and Cook. He claimed that:

the book is not wholly satisfying, because the argument remains on a purely theoretical plane throughout. The reader cannot fail to wonder about the magnitude of the problem under discussion in the real world. Some empirical research would not only have made the book more interesting but may also have increased the author’s contribution to economic analysis.

(Grant 1962: 125)

The line of thinking here seem to be that the price mechanism in practice does not seem to produce chaos, so Richardson is worrying about a problem that does not really matter and therefore it is safe to continue with conventional theoretical analysis. The reviewers seem blind to Richardson’s key point: the traditional theory has a logical flaw and chaos is avoided, insofar as it is avoided, because supply decisions are reached in ways fundamentally different from those posited by traditional theory. This being so, it is conceivable that attempts to make the world resemble the traditional theoretical world more closely in terms of the competitive rules of the game may result in inferior patterns of resource allocation, due to the world then functioning in a more chaotic manner or entrepreneurs in general becoming more hesitant about investing. Thus, even without any buttressing from Debreu’s make-believe world of complete contingent commodity markets, the traditional theory seemed to have been quite acceptable to Richardson’s reviewers as an ‘as-if’ approximation of how the world works.

In taking issue with Loasby here on the impact of Debreu’s success on the reception of Information and Investment I am not denying that the timing of its release might have been more fortuitous. Indeed, there are several reasons to believe that the market for Richardson’s message has ripened steadily since 1960 and that the book would have fared far better had it been published around 1972, with Richardson’s originally intended title and including material from his 1972 article, which is logically linked with it (see Foss 1994, on the relationship between Richardson 1960 and 1972):

1 One might expect traditional theory to look less good as an approximation when the ‘golden age’ of economic growth came to an end and excess capacity creation would no longer rapidly tend to be rendered non-problematic by ongoing demand growth. During the golden age interest in investment co-ordination problems tended to centre on the question of which firms should exit from markets suffering from chronic excess capacity due to changes in global competitive conditions – for example traditional staple industries such as cotton textiles (see Miles 1968) and wool textiles (see Wool Textile EDC 1969) – and on the possibility of dysfunctional defensive investment (Lamfalussy 1961). Richardson, however, had not focused on exit games under conditions of gross immobility of capital and human resources. Nowadays, with frequent periods of recession and new investment occurring despite chronic overcapacity in many modern industries (for example the motor vehicles industry), it is not easy to dismiss Richardson’s work as empirically insignificant.

2 Those who were less enamoured with the price mechanism doubtless learnt a lot more about the nature of the co-ordination problem in the decade after Information and Investment appeared. Attempts at indicative planning, such as those of the UK Labour Government in the late 1960s, and the ‘balanced versus unbalanced growth’ debate in development economics may have aroused a greater recognition of complementary aspects of investment, as well as of the difficulty of ensuring the right amount of investment in any one sector if directives were not to be given to individual firms and communication between them was not allowed. It is easy to see why Richardson’s (1971) timely article ‘Planning versus competition’ was so swiftly reprinted in Wagner and Baltazzis (1973). Had his 1960 book not already been published, Richardson’s (1969) report on collusive tendering in the UK’s heavy electrical engineering industry would have made a powerful empirical addition to it, since it embraces both the complementarity problem (a capacity problem due to the electricity industry expanding rapidly in keeping with the National Plan, only to find that most of the rest of the UK economy did not) and the question of whether market imperfections might enhance dynamic efficiency.

3 It was around 1972 that the so-called Crisis in Economic Theory really seemed to break out, with widespread criticism (for example Kaldor 1972) of the kind of abstract and institutionally implausible research that Debreu’s work had helped to foster.

Had Richardson’s work attracted wide attention during the early 1970s, it is conceivable that a good deal of subsequent work on industrial economics would have been done differently. In particular, those involved with the development of contestability theory would have had reason to be rather more cautious in advocating the removal of entry barriers in industries such as passenger aviation and financial services that have since suffered from severe adjustment problems (see further Earl 1995: 305–9).

NETWORKS, INSTITUTIONS AND ACADEMIC SEARCH PROCESSES

The sheer volume of potentially relevant material that academics might find worth reading makes it seem inappropriate to try to make sense of the fate of particular contributions to knowledge in terms of a perspective which sees academics as if they know not merely which kinds of ideas they like but also where to find them. Though some economists in the 1960s may have been deterred from reading Richardson (and even Debreu) by contemporary reviews, and though some of them may have seen his work and decided not to read it because it did not fit with their growing taste for technical rigour, it is unlikely to be the case that most economists currently working have sized up Richardson’s work with the aid of such reviews and have decided not to read it in detail, or, like his reviewers, have read it and decided not to take his ideas on board. A more plausible hypothesis is that most economists are simply unaware of his contributions and use search processes or move in social circles that are not conducive to discovering what Richardson has had to say.

In the analysis of product life-cycles of consumer products it is commonly recognised that social factors play a major role in determining how much attention potential buyers pay to new products and whether or not they experiment with them. The same seems to hold in academia and, as with consumer markets, some people may have more influence than others. Networks of personal contacts would have had a far smaller role to play in shaping the esteem attached to particular contributions to knowledge if: (1) researchers habitually searched for relevant materials with the aid of indexing and abstracting systems in the manner that libraries nowadays try to inculcate among students; and (2) such systems covered older works as well as recent contributions. In some cases, the confidence of modern librarians in their information systems is such that they see lecturing staff not as experts in their subject areas who point students speedily to pertinent contributions but, rather, as dangerous individuals whose use of reading lists and inclination to place favoured material in restricted loan sections is liable ‘to bias students’ reading’ (to quote the words of the Librarian of Lincoln University). However, I suspect that until recently very few academics made great use of such potential as existed for systematic search, with the result that networks were of vital significance.

When the bulk of Richardson’s work appeared there were relatively few economics journals with which to keep up to date. However, this was also a period in which indexing systems were poorly developed and economists were not accustomed to making extensive use of abstracts (the Journal of Economic Abstracts commenced publication as late as 1963 and only turned into the more extensive Journal of Economic Literature in 1969). It is also probably fair to say that it was only in the 1970s that the Harvard system of referencing really caught on and made it far easier for potential readers to get a flavour of a work by examining its bibliography. In terms of presentation and layout, the reprint of Information and Investment is remarkably uninviting to the casual browser of the 1990s, for, as already noted, Richardson’s works were typical of their time – the world of infrequent references scattered around in footnotes and of a notable absence of the use of section headings in chapters and papers.

Prior to the age of information and the development of sophisticated indexing systems, scholars who became aware of Richardson typically either would have done so by serendipity (for example, stumbling across his books or articles whilst looking purposively for something else that happens to be physically adjacent) or would have discovered them to a greater or lesser extent with the aid of networks. Seven main types of connections promote the discovery of contribution to knowledge, and some of them can be illustrated by reference to tales of ‘routes to Richardson’ reported to me by contributors to the Richardson colloquium held in Oxford in January 1995:

1 Being a pupil or colleague of the author in question, or a student with an intellectual lineage traceable back to the author. For example, given their associations with St John’s College, Oxford, it should be no surprise that John Kay and Leslie Hannah have been influenced by Richardson. John Nightingale’s lineage, by contrast, links Oxford and Australia: he recalls that Richardson was one of a number of authors (including Penrose, Downie and Andrews) whose recent works were discussed by Don Lamberton in a final-year undergraduate unit at the university of New South Wales in the mid-1960s – Lamberton had recently returned to Australia after meeting Richardson when working on his DPhil at Oxford.

2 Seeing a work that cites the author, or at least cites a work that cites the author. For example, the writings of Loasby (particularly his 1976 book) introduced the name of Richardson to myself, Nicolai Foss (who discovered Richardson around the same time also from the citation in Leijonhufvud (1968: 69–70)) and Richard Langlois. In turn, Richard Arena reports that he first saw Richardson mentioned in Earl (1983b). It is, of course, common for academics to prime their markets (or assert their property rights) via preliminary publications, such as articles and discussion papers, that foreshadow their major works whilst pre-emptively staking their claims as market leaders in particular areas of research. Richardson’s articles from the 1950s pave the way directly to his (1960)book in intellectual terms. He also certainly helped his readers discover his earlier work by his own citations (oddly enough, in his 1972 paper his footnote reference (p. 891) to Information and Investment lists it as published in 1961, not 1960!). Though he did not engage in forward citation, his work was helpfully discussed by his Oxford colleague Malmgren (1961) in the Quarterly Journal of Economics at a very early stage. This should have helped stir up interest among potential readers in America who were not regular readers of Oxford Economic Papers or the Economic Journal. Malmgren’s work, unfortunately, seemed to suffer much the same initial fate as Richardson’s.

3 Being taught by someone familiar with the author’s work despite not being a direct or indirect pupil of the author. For example, Mark Casson commented that ‘I think Richardson (as well as Coase, Penrose, etc.) was on the undergraduate reading list at Bristol, and I used to read the things on the list. So I never “discovered” any of these writers – I was simply directed to them. Hence I never regarded them as particularly unorthodox.’ Neil Kay was introduced to Richardson’s work as a pupil of Loasby at Stirling University. Gavin Reid used a Richardson (1964a) text as a second-year undergraduate at Aberdeen University in 1966–7 when looking for a short, clear conspectus of basic economics, but thinks that J. N. Wolfe, a close friend of Richardson, introduced him to Information and Investment in the early 1970s when he was a graduate student at Edinburgh University.

4 Meeting with the author, or with other scholars familiar with the author’s work, at conferences and/or meetings of professional societies or during the author’s periods of sabbatical travel. In this connection we might note that Richardson’s impact in North America ought to have been greater given that Information and Investment was in part written whilst he was on a Rockefeller Foundation fellowship that left him free to ‘indulge in stimulating conversations with colleagues at Harvard and the University of California at Berkeley’ (Richardson 1960: xv).

5 Receiving a word-of-mouth recommendation from a colleague. For example, Paul Robertson believes that he first heard of Richardson’s 1972 paper around 1986, from Dick Merrett, a fellow business historian in Melbourne, who in turn had just read it for the first time himself.

6 For academics in the future, the Internet is likely to become the ultimate networking device for affecting the spread of new ideas (see further MacKie-Mason and Varian 1994; Goffe 1994 – references to which my own attention was drawn via an e-mail from Don Lamberton).

7 Publishers’ mailing lists and catalogues, and their use of particular ‘names’ to endorse their products. For the second edition of Information and Investment, David Teece and Oliver Williamson provided supportive comments: the fate of the first edition might have been very different had it come with a foreword from, say, Hicks (who had read it in draft) or Shackle. In future, online indexes of books and contents listings (such as Bridges to Blackwell/New Titles On-Line) may have a major role to play in enabling academics to decide what to order without being overwhelmed by printed catalogues, so choices of titles and contents designs will become even more important: we should all take note of Richardson’s view that his publisher’s favoured title Information and Investment was unfortunate, since it led to the work being catalogued in libraries alongside books on the Stock Exchange (see his preface to the 1990 edition, p. xvii).

The existence of so many potential linkages is significant given the danger that any single aid will be of limited effectiveness. If academics are working under pressure they may not register signals as they encounter them, or may not bother to act upon them. My own route to Richardson illustrates this graphically. When, as a postgraduate student in 1977, I read Richardson (1972), inspired by the discussion in Loasby (1976), I realised that I had encountered it before, at high school in 1972 – the trouble was that, in giving us such memorable examples from ‘the latest Economic Journal that has arrived from the town library’, my teacher had not mentioned Richardson by name as the author. Later, on rereading Leijonhufvud (1968), a work which had played a crucial role in getting me hooked on the economics of uncertainty, I noticed for the first time the footnote references to Richardson (1959), in precisely the part of the book that had made such an impact. Later still, when collating old subject outlines I discovered that my final-year industrial economics reading list from Alan Hughes’s lectures at Cambridge included Information and Investment, but somehow I had not followed it up at the time.

Whether or not recommendations or citations are followed up may depend considerably on the availability and anticipated quality of the work in question. Certainly, in using the SSCI to compile the Appendix to this chapter I was struck by the obscurity of many of the journals in which Richardson has been cited (Assistance from librarians is required even to track down the full names of some of them, let alone access copies). Richardson’s articles, being in major English-language journals, are relatively easy to obtain at a moment’s notice in older libraries, as are his books, but all could easily be dismissed on account of their age by current scholars unless they have been discovered by more modern secondary sources of note in which their virtues have been extolled at length.

To conclude this section I would like to emphasise that when a scholar has to go to some trouble to obtain a work – for example, an interlibrary loan to a recently established institution – learned societies have a major role to play in determining whether it will look sufficiently attractive in prospect to seem worth chasing, as well as whether it gets discovered in the first place. Although it is rare for such societies to insist that members conduct their research in a particular manner – unlike trade associations, who may debar from membership those whose standards of work do not meet with association norms – their ability to control what gets presented at their conferences or what gets published in their official journals means they have a major gatekeeping role in respect of the marketing of contributions to knowledge. A further aspect of this professional control is the ability to determine which journals are abstracted in the society’s abstracting publications. This is important not merely because articles published in unlisted journals have a smaller chance of being discovered but also because librarians, concerned to see that their investments are thoroughly used, may refer to the places in which a journal is abstracted as criteria for deciding whether or not to agree to take out a subscription – so, woe betide the economics journal which is not abstracted in ABl-lnform and the Journal of Economic Literature.

Mere publication of an article signals to the academic community that it has been through a pretty stiff competitive refereeing process if it is published in a dominant professional grouping’s generalist journal, or signals the height of refereeing hurdles and the likely style and content if it is published in a subdisciplinary or heterodox journal. (It is probably fair to suggest that when Richardson published frequently in Oxford Economic Papers in the 1950s and 1960s, this journal was much less of an international organ than it is today.) Commercially published journals serve a similar signalling role, and, of course, many of these are associated with academic societies or networks. Firms that publish a large number of journals of high quality have a incentive to maintain their standards as they add new journals to their catalogues, for fear of damaging their overall image and hence the subscriptions they can command. Editorial boards of reputable academics signal the standards that are being targeted even if no learned society sponsors the journal. Likewise, in respect of book publishing, catalogue branding is extensively used to signal the type of book to potential purchasers: most publishers run a variety of imprints and under any particular imprint may also include a number of series of books of particular kinds.

Richardson’s work on economic organisation and co-ordination has been widely used despite so far failing to become part of the core of microeconomic theory. It also provides valuable perspectives for viewing the operations of academia, encouraging us to look for networks and other institutional devices that assist academics to reduce co-ordination difficulties. The risk that academics will unwittingly reinvent each other’s ideas or pursue dysfunctional lines of inquiry owing to their ignorance of particular contributions is reduced to the extent they can search systematically with the aid of subject and citation indexes, abstracts and book reviews or contents listings. In the past, haphazard methods of research and weaker networking/indexing made it all too easy for scholars to to be unaware of works that they would have welcomed or that would have forced them to rethink their ideas. It was not wise to presume that if a contribution to knowledge was of a high standard this would necessarily be swiftly reflected in its rate of citation or the number of copies in circulation. Now, as the twentieth century comes to an end, we are entering a new world where information technology will permit scholars to operate in a far less haphazard manner as they attempt to discover and screen contributions for their likely usefulness. Much screening will take place on-screen and ideas will be able to spread far more rapidly so long as they have been judiciously titled and summarised. Even so, older contributions or contributions in obscure journals may remain at risk of being neglected. The Appendix that follows is offered not merely by way of documenting some of the use made of Richardson’s work but also to concentrate readers’ minds on just how narrow are their normal ranges of reading compared with the range required if one is to be able truthfully to say ‘I know the literature’.

Citations of G. B. Richardson recorded in the Social Sciences Citation Index, 1969–94

Note: Each entry is listed in terms of the author making the citation (longer names may be truncated and only the first author is shown in the case of joint works), the name of the journal in which the citation occurs (which may be abbreviated), and by the volume number, the number of the first page of the article and the year of publication.

1 I would like to thank Michael Brooks for many useful comments on an earlier version of this paper, which has also benefited from comments by the editors and the publisher’s referee, and from correspondence with George Richardson (who provided some very useful autobiographical notes) and Fred Lee.

REFERENCES

Baudier, E. (1961) ‘Review of G. Debreu’s Theory of Value’, Econometrica 29: 259–60.

Blois, K. J. (1972) ‘Vertical quasi-integration’, Journal of Industrial Economics 20: 253–71.

Borch, K. (1973) ‘The place of uncertainty in the theories of the Austrian school’, in J. R. Hicks and W. Weber (eds) (1973) Carl Menger and the Austrian School of Economics, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Clark, J. M. (1923) Studies in the Economics of Overhead Costs, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Clarke, R. and McGuinness, T. (eds) (1987) The Economics of the Firm, Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Cook, P. L. (1964) ‘Review of G.B. Richardson’s Information and Investment’, Economic Journal 74: 168–9.

Debreu, G. (1959) Theory of Value, New York: Wiley.

Devine, P. J., Jones, R. M., Lee, N. and Tyson, W. J. (1976) An Introduction to Industrial Economics, 2nd edn, London: George Allen & Unwin.

Dobb, M. H. (1937) Political Economy and Capitalism, London: Routledge.

Earl, P. E. (1983a) ‘A behavioral theory of economists’ behavior’, in A. S. Eichner (ed.) Why Economics is Not Yet a Science, Armonk , NY: M. E. Sharpe, Inc.

—— (1983b) The Economic Imagination, Brighton: Wheatsheaf.

—— (1993) ‘Epilogue: whatever happened to P. W. S. Andrews’s industrial economics?’, in F. S. Lee and P. E. Earl (eds) The Economics of Competitive Enterprise: Selected Essays of P.W.S. Andrews, Aldershot: Edward Elgar.

—— (1995) Microeconomics for Business and Marketing, Aldershot: Edward Elgar.

Foss, N. (1994) ‘Cooperation is competition: George Richardson on coordination and interfirm relations’, British Review of Economic Issues 16: 25–49.

George, K. D. and Joll, C. (1981) Industrial Organisation, 3rd edn, London: George Allen & Unwin.

Goffe, W. L. (1994) ‘Computer network resources for economists’, Journal of Economic Perspectives 8: 97–119.

Grant, J. McB. (1962) ‘Review of G. B. Richardson’s Information and Investment’, Economic Record 38: 125.

Greer, D. F. (1992) Industrial Organization and Public Policy, 3rd edn, New York: Maxwell-Macmillan.

Hahn, F. H. (1961) ‘Review of G. Debreu’s Theory of Value’, Journal of Political Economy 69: 204–5.

Harrell, C. (1960) ‘Review of G. Debreu’s Theory of Value’, Southern Economic Journal 27: 149–50.

Harris, L. (1965) ‘Review of G. B. Richardson’s Economic Theory’, Economica 32: 236–7.

Hay, D. A. and Morris, D. J. (1979) Industrial Economics: Theory and Evidence Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hicks, J. R. (1945) Value and Capital, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hurwicz, L. (1961) ‘Review of G. Debreu’s Theory of Value’, American Economic Review 51: 414–17.

Kaldor, N. (1972) ‘The irrelevance of equilibrium economics’, Economic Journal, 82: 1237–55.

Kay, J. A. (1993) Foundations of Corporate Success, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Keynes, J. M. (1936) The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, London: Macmillan.

Lamfalussy, A. (1961) Investment and Growth in Mature Economies: The Case of Belgium, London: Macmillan.

Lee, F. S. (1993) ‘Philip Walter Sawford Andrews, 1914–1971’, in F. S. Lee and P. E. Earl (eds) The Economics of Competitive Enterprise: Selected Essays of P. W. S. Andrews, Aldershot: Edward Elgar.

Leijonhufvud, A. (1968) On Keynesian Economics and the Economics of Keynes, New York: Oxford University Press.

Loasby, B. J. (1976) Choice, Complexity and Ignorance, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

—— (1989) The Mind and the Method of the Economist, Aldershot: Edward Elgar.

MacKie-Mason J. K. and Varian, H. (1994) ‘Economic FAQs about the Internet’, Journal of Economic Perspectives 8: 75–96.

Malmgren, H. B. (1961) ‘Information, expectations and the theory of the firm’, Quarterly Journal of Economics 75: 399–421.

Martin, S. (1993) Advanced Industrial Economics, Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Miles, C. (1968) Lancashire Textiles: A Case Study of Industrial Change, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press/NIESR.

Muth, R. F. (1961) ‘Rational expectations and the theory of price movements’, Econometrica 29: 315–35.

Penrose, E. T. (1959) The Theory of the Growth of the Firm, Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Phlips, L. (1988) The Economics of Imperfect Information, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Pickering, J. F. (1973) Industrial Structure and Market Conduct, London: Martin Robertson.

Porter, M. E. (1980) Competitive Strategy, New York: Free Press.

Power, J. H. (1961) ‘Review of G. B. Richardson’s Information and Investment’, American Economic Review 51: 761–2.

Reid, G. C. (1987) Theories of Industrial Organization, Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Richardson, G. B. (1959) ‘Equilibrium, expectations and information’, Economic Journal 69: 223–37.

—— (1960) Information and Investment: A Study in the Working of the Competitive Economy, Oxford: Clarendon Press.

—— (1964a) Economic Theory, London: Hutchinson.

—— (1964b) ‘The limits to a firm’s rate of growth’, Oxford Economic Papers 16: 9–23.

—— (1965) ‘The theory of restrictive trade practices’, Oxford Economic Papers 17: 432–49.

—— (1966) ‘The pricing of heavy electrical equipment: competition or agreement?’, Bulletin of the Oxford University Institute of Economics and Statistics 28: 7392.

—— (1967) ‘Price notification schemes’, Oxford Economics Papers 19: 355–65.

—— (1969) The Future of the Heavy Electrical Plant Industry, London: BEEMA.

—— (1971) ‘Planning versus competition’, Soviet Studies 22: 433–47.

—— (1972) ‘The organisation of industry’, Economic Journal 82: 883–96.

—— (1975) ‘Adam Smith on competition and increasing returns’, in A. S. Skinner and T. Wilson (eds) Essays on Adam Smith, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

—— (1990) Information and Investment: A Study in the Working of the Competitive Economy, 2nd edn, Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Robinson, J. V. (1954) ‘The impossibility of profits’, in E. H. Chamberlin (ed.) Monopoly and Competition and their Regulation, London: Macmillan.

Scherer, F. M. and Ross, D. (1990) Industrial Market Structure and Economic Performance, 3rd edn, Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Schmalensee, R. and Willig (eds) (1989) Handbook of Industrial Organization, vol. 1, Amsterdam: North-Holland.

Stigler, G. J. (1982) The Economist as Preacher, Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Tirole, J. (1988) The Theory of Industrial Organization, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Wagner, L. and Baltazzis, N. (eds) (1973) Readings in Applied Microeconomics, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Williams, B. R. (1949) ‘Types of competition and the theory of employment’, Oxford Economic Papers 1 (new series): 121–44.

Wool Textile EDC (1969) The Strategic Future of the Wool Textile Industry, London: HMSO.

Young, A. (1928) ‘Increasing returns and economic progress’, Economic Journal, 38: 527–42.

Young, W. and Lee, F. S. (1993) Oxford Economics and Oxford Economists, London: Macmillan.