INFORMATION, SIMILAR AND COMPLEMENTARY ASSETS, AND INNOVATION POLICY

INTRODUCTION

In Information and Investment: A Study in the Working of the Competitive Economy, G. B. Richardson investigates the effects of imperfect knowledge on investment decisions to demonstrate that the equilibrium situations posited by neoclassical economists are unlikely to be achieved. In particular, Richardson shows that it is improbable that the investment decisions of individual producers will lead to socially optimal outcomes because, in the absence of knowledge as to the plans of their competitors, businesses will either over-or underinvest in capacity when they perceive an opportunity for expansion. If each producer of a good believes that it is in a position to take full advantage of a probable increase in demand, all producers will invest in new capacity, leading to excess expansion overall and lost profits for individual investment units. If, however, all producers assume that their competitors are likely to invest, then none will expand and the outcome will again be sub-optimal from the standpoint of consumers as well as producers. As a result, the degree of information provided by the market itself is insufficient to maximise welfare, and co-ordination among producers is needed to reduce uncertainty and allow rational investment decisions. This co-ordination can take a variety of forms, including collusion (the exchange of information among producers) and, at an extreme, central planning, in which a single set of decisions is made on behalf of all producers of a good.

Although Richardson does not place much emphasis on innovative situations, it is clear that his analysis applies a fortiori when there is uncertainty, not only about the investment decisions of other producers, but also about such factors as the size of the market for an untried product or the technical efficacy of the product or the production process. In an innovative situation, the limitations that poor information may place on the willingness to invest are so substantial that potentially promising outcomes may never be investigated in practice, leading (as in any case of underinvestment) to reductions in social welfare. To overcome this problem, government action may therefore be justified, either to improve the quality of information available or to enhance the distribution of existing information. As in Richardson’s own analysis, these improvements and enhancements may be accomplished through ‘collusion’ or ‘planning’, including government efforts to bolster market-based outcomes as well as direct government intervention in the investment process.

In this chapter, in order to reach some tentative indications of the proper scope of government innovation policy, I explore several of the practical problems involved in generating and distributing information in innovative situations. As the field is so broad, I give special attention to three issues. In the next section I discuss the general problem of the communication of information that is already known by some people but which has not yet been spread to all users who might potentially benefit from it. The section entitled ‘Information, Similarity and complementarity’ (pp. 275–8) concentrates on the ways in which Richardson’s concept of similar and complementary activities can be applied to determining which organisational forms are most conducive to innovation. The final issue that I investigate in some depth (see ‘Innovation and industry maturity, pp. 278–82) is the problem of promoting innovation in established firms that produce ‘mature’ products. While my argument is based heavily on Richardson’s work in Information and Investment and in his article on ‘The organisation of industry’ (1972), I have been perhaps influenced most by his argument that ‘The appropriate methodological position is surely one of tolerance and eclecticism, of choosing the approach and terminology which seems to suit the subject in hand, of indiscriminate plundering of concepts from other fields whenever they seem illuminating’ (Richardson 1990: 41, n. 1).

INFORMATION AND INNOVATION

Uncertainty and ignorance

Before proceeding further, I should indicate what I mean by ‘innovation’. In an exchange in the Economic Journal, Stoneman and Diederen adhere to a strict Schumpeterian division between invention, innovation and diffusion in which innovation means ‘the development of [new] ideas through to the first marketing or use of a technology’ and diffusion refers to ‘the spread of new technology across its potential market’ (Stoneman and Diederen 1994: 918). In the same issue, however, Metcalfe argues that ‘it is not helpful to treat innovation and the diffusion of innovation as separate categories, in fact they are inseparable, with feedback from diffusion being one of the critical elements shaping how a technology is developed’ (Metcalfe 1994: 931). The position taken here is similar to Metcalfe’s, although the reasoning differs somewhat. In addition to the feedback and subsequent reshaping of the original innovation that may result from diffusion, innovation may be undertaken repeatedly in different contexts as diffusion proceeds. The use of the turbine principle resulted in crucial innovations in both electricity generation and ship propulsion, and the widespread adoption of small electric motors was as important an innovation in Western European industry in the 1950s as it had been in the US thirty years earlier. Thus ‘innovation policy’ refers to government actions, or inactions, designed to promote both the spread and the application of technologies.

It is now generally conceded that the extent to which relevant knowledge is available is one of the most important factors influencing the innovation process, including the primary stage of invention. If knowledge is limited to a small group of people or firms, opportunities for change may be stifled. This is especially true if the knowledge is restricted to operators in a single industry. Hence the development of institutions to facilitate the spread of knowledge may be a vital contribution to the growth of technological capabilities in the economic system as a whole.

But, just as there are various reasons why knowledge may be lacking, there are also various tools that may be needed to tackle the problem. Uncertainty refers to the inherent inability of people to know exactly what will happen in the future. People lack information because the necessary data do not yet exist, and by the time the data are available they will have lost some of their relevance because the past cannot be changed. Although uncertainty may be reduced as experience accumulates and better predictions can be made, it can never be eliminated altogether. Ignorance, in contrast, applies in cases in which knowledge or information is already available somewhere or is potentially discoverable but some or all of the potential users have not yet acquired that knowledge. Ignorance may prevail, therefore, before an invention or an innovation has been made, as well as during the diffusion stage, but the incidence of ignorance changes. Prior to an invention or the discovery of a principle, everyone is ignorant of the answer to a particular problem. Subsequently, some people know the answer but others remain ignorant until diffusion occurs.

These distinctions have important implications because uncertainty and ignorance are best covered by different sets of policies. When there is uncertainty, policy-makers are concerned with reducing the uncertain area to the smallest extent feasible and also, perhaps, with providing some way of reducing the impact of failure on those who nevertheless make incorrect judgements. Ignorance requires a group of different approaches depending on its nature. When there is no known answer to a problem that is capable of being solved, a strategy of discovery is indicated. In this case, the appropriate policies could include a programme of pure research to discover underlying principles, or one of applied research and development to bring known principles to bear on a problem. But when potential solutions are already available, the task of policy-makers may be to find some way of bringing those solutions to the attention of people or organisations with problems (problem-holders) and, equally importantly, to bring problem-holders to the notice of current or potential solution-holders.

When taken together, uncertainty and ignorance involve both the generation and the communication of knowledge. Although both of these factors are susceptible to government policy, different instruments are appropriate. A great deal has been written on policies for the generation of innovative knowledge (e.g. Nelson 1993), but systematic analysis of the communication of such knowledge is relatively rare. Thus my concern here is primarily with the implications of the communication process for policy-makers.

A model of the communication process

The existence of knowledge provides no guarantee that it will be correctly perceived by those who can use it profitably. Would-be users must first be aware of what they need to know, and then they must find a way of cheaply and efficiently locating the necessary knowledge. To take these factors in turn, the way in which problems are perceived depends on the context in which they are encountered, as Clark (1985) has argued.1 This has frequently been recognised as one aspect of the failure of firms in mature industries to adapt to fundamental change, as is discussed below, but it is also of importance to firms in earlier stages of development. Clark suggests that there are ‘design hierarchies’ that determine search patterns. For example, the early triumph of the internal combustion engine, as opposed to electric or steam power, set the context in which later developments in the automobile industry took place. Even quite early in the development of the automobile, designs for starting mechanisms, cylinder configuration and other features were viewed in terms of the prior commitment to internal combustion, petrol-fuelled engines (Clark 1985: 243).

Stinchcombe calls the information that is of central concern to a particular organisation the ‘news’ (Stinchcombe 1990: 3). Not all information is ‘news’. Indeed, most information is of no use to an organisation, whose problems are therefore two-fold. In order to solve its problems, an organisation must first decide on what kind of ‘news’ is needed and then locate it, but it must also find efficient ways of filtering out information that is not ‘news’. Various common means are used to accomplish this, including the adoption of heuristics based on the use of sources that have been valuable in the past, such as suppliers, customers and the trade press, and the adoption of organisational structures that are designed to concentrate on the collection and processing of the ‘news’ while reducing to a minimum the collection of useless information (Chandler 1962; J. D. Thompson 1967).

But the problem of ignorance does not only affect users of information. Generators of knowledge (solution-holders) may also have trouble in identifying the problems to which their new information can profitably be applied and in locating probable users, or problem-holders.2 Neoclassical economists, including the so-called ‘New Growth’ and ‘New Trade’ theorists, often emphasise the negative effects that ‘spillovers’ may have on research and development efforts.3 Grossman and Helpman, for example, have assumed, that ‘profit maximizing and far-sighted entrepreneurs invest in research and development in order to capture monopoly rents from innovative products’ (Grossman and Helpman 1991: 517–18). In a somewhat weaker statement, Romer argues that ‘profit-maximizing agents make investments in the creation of new knowledge and they earn a return on these investments by charging a price for the resulting goods that is greater than the marginal cost of producing the goods’ (Romer 1990: p. S89). But under certain circumstances it is possible to reconcile the institutions that protect the monopoly positions of entrepreneurs, such as the patent system, with other institutional arrangements that will allow for the wider economic and social benefits that may result from the spread of knowledge.

In fact, while conceding that inventive and innovative activity may be spurred on by an ability to capture monopoly rents, it is illogical to suppose that entrepreneurs will act only if they think that they can attract supermarginal prices on all of their transactions. In reality, solution-holders may be in a position to segment their markets and to charge different prices to different users. When an innovation has more than a single use, solution-holders could extract monopoly or near-monopoly rents in one industry (perhaps their own) and then license the innovation to producers in other industries at prices that bring them lower profits. Indeed, as long as they did not erode their monopoly positions in some markets, they would be non-rational if they did not permit the diffusion of an innovation up to the marginal cost of production, including the costs of spreading the necessary information.4

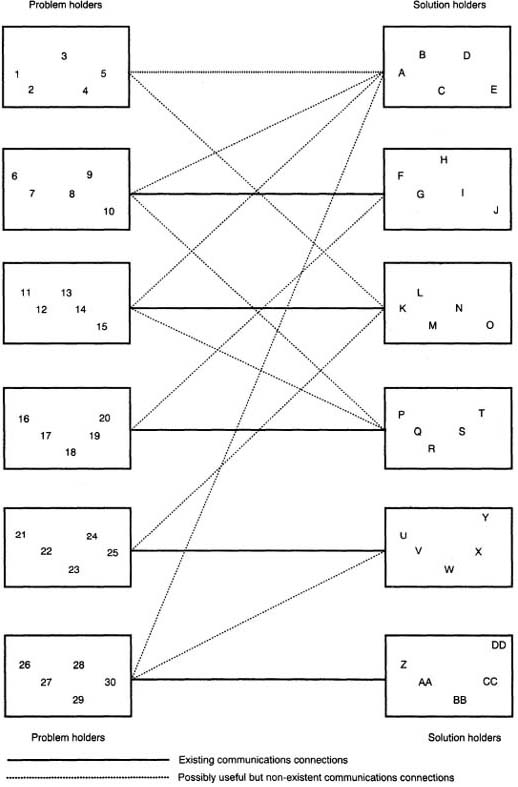

Thus solution-holders may well welcome the development of efficient institutions to bring their innovations to the notice of problem-holders even if they receive reduced marginal returns. To the degree that particular sources of ‘news’ are not encompassed by the heuristics of problem-holders, however, they are unlikely to be perceived. Moreover, even when they are noticed, outsiders may lack credibility as solution-holders simply because they are not members of the customary networks of contacts employed by problem-holders. In some cases, this may make it hard for sources of ‘news’ to find any listeners if they are beyond the borders of all networks. The spread of adoption of an innovation from industry to industry by a process of analogy will also be hampered if there is no overlap in the customary networks employed in different industries: if producers in industry A are unaware that they share problems with producers in industry X they are unlikely to consult the same sources of solutions. The upshot could be a situation like that shown in Figure 14.1, in which problem-holders have heuristic contacts with some sources of ‘news’5 (the solid lines) but lack ways of communicating with other sources from which they may possibly profit (the dashed lines).

Figure 14.1 Existing and potentially useful relationships between problem holders and solution holders

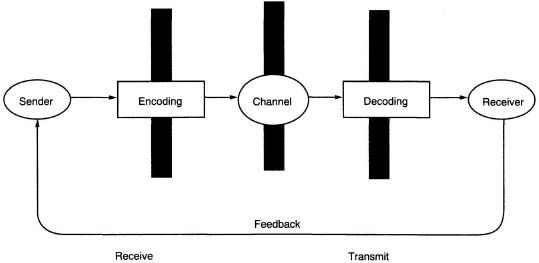

The problem for firms – both sources and users of ‘news’ – is therefore to find some way of establishing the necessary communication channels, but the means of doing this will depend on why the existing channels of communication are inadequate. An elementary model of communication can help to highlight the issues. Figure 14.26 shows the basic stages involved in communicating information from a source (the sender) to a target (the receiver). In general, the sender initiates the communication, which can take the form of either information or a request for information. This information (or request) cannot be sent directly, however, but contains a subjective element because it must first be encoded by being translated into symbols that the sender believes to be an accurate representation of the information. At this point, the encoded information has become a message, which may take many forms, such as speech or a written text. The message is then sent through a communication channel or medium. For spoken words the channels could be, inter alia, air, radio or telephone, while a written message could be in the form of a letter, newspaper, etc. Once received, the message is then decoded, again a subjective process that involves interpretation in a way that the receiver believes will allow the message to be understood correctly. Finally, the process may be reversed, with the receiver sending another message as feedback to the original source.

Although codification may simplify the communication process, the transmission of a message or question by no means ensures that it will be accurately received, let alone acted upon. The communication process presents pitfalls at every stage that may undermine the intentions of the sender or receiver. The most obvious problem, perhaps, is that the intended receiver may not be ‘listening’ or may be tuned into the wrong channel, as in Figure 14.1, but there are many other sources of ‘noise’. For example, the encoding or decoding may be inaccurate. If the code is to be interpreted successfully the sender and receiver must have agreed on the meanings of the symbols used, but when a message is broadcast impersonally there is no reason to believe that an agreement would have been reached in advance. This is especially true of technical data which require specialised knowledge on the part of both parties. A source of innovative information must know how to express the innovation in terms that potential problem-holders can relate to, but since understanding is contextual, solution-holders may need to employ differently phrased messages to reach different classes of problem-holders. Thus sources may require a deep understanding of the contexts of many different potential users if a versatile innovation is to be sold widely. Similarly, questioners (problem-holders who are searching for solutions) must phrase their questions accurately in order to elicit relevant answers, and the potentially best answers from a technical perspective may be sent in languages that some problem-holders do not know.

Note: Vertical shaded bars indicate noise

Figure 14.2 A model of the communication process

The channel of communication may also be a source of noise. As has been shown, potential communicators often find it efficient to restrict their messages to channels that have been useful in the past. They may ignore unfamiliar locations or media and thereby miss the information that they need. Furthermore, different recipients may need different degrees of ‘logical depth’ in their messages (Davies 1995). Logical depth refers to the amount of knowledge that the recipient requires to be able to operationalise the material in the message. When the message relates to material that is already largely familiar to the recipient, a form of shorthand may be sufficient, but a message concerning totally unfamiliar concepts may need to provide great detail in order to achieve a high degree of logical depth. As in the case of encoding/decoding problems, the difficulty is not one of knowledge (because the necessary information already exists) but, rather, of ignorance and inadequate communication. Efforts to improve the efficiency of communication can therefore pay significant dividends by promoting the quicker solution of problems and discouraging duplicative research.

Bridging communication gaps

Entrepreneurship

Communication gaps may be tackled in the private sector through what Kirzner (1973) calls ‘entrepreneurial alertness’. To Kirzner and other Austrian economists, the role of the entrepreneur is to perceive situations in which problems and solutions already exist but have not been brought together, and then to improve efficiency by effecting a reconciliation. Such people may intentionally or accidentally become aware of situations in which potential senders and receivers of information on innovations have failed to make meaningful contact and then arrange for effective communication in return for a share of the resulting profits. Thus entrepreneurs may act as arbitrageurs by locating channels of communication, but they may also play a major role by reducing noise in the system. They may do this, for example, by acting as interpreters who present solutions in a language that problem-holders can understand, or by making problems intelligible to solution-holders by providing supplementary information that adds logical depth to messages.

Nevertheless, valuable though alertness may be, entrepreneurs may also find their work impeded by communication barriers. If they are outside established communications networks, entrepreneurs may lack credibility. Furthermore, entrepreneurs face the double task of learning about both problems and solutions in fields in which they may otherwise have no experience. And if existing firms resist their advice the only way that entrepreneurs have of exploiting their alertness may be by setting themselves up in competition, which may be expensive and risky. Although entrepreneurs are on occasion successful, especially when there is a major shift in technological paradigms, in other circumstances change may be undertaken more efficiently by individuals or organisations that are already either problem-holders or solution-holders and therefore know at least some of the language and the technical problems involved.

Standards

Communications difficulties may also be mitigated by increasing the general level of alertness in one or several industries. If noise at the encoding and decoding stages is a major drawback, then the creation of standards of language and other characteristics can ease the problem of reconciling the efforts of problem-holders and solution-holders. As time passes, each group (like members of adjacent tribes) may gain a good knowledge of the others’ vocabulary and syntax, which could increase alertness on all sides and lead to higher levels of diffusion and innovation. But such a process could take considerable time, especially if the holders of problems and solutions are not adjacent but occupy distant ‘social locations’. By speeding up the communication process, the conscious creation of a common language could therefore be valuable. The question is whether a government policy is needed or whether the development of a common language can be negotiated privately.

We can get an insight into this by examining the mechanisms by which standards have been developed in the past. Many items that are standardised, such as radio frequencies or the threading of screws, can be regarded metaphorically as languages because standardisation permits different users to ‘speak’ to each other, that is, to be compatible. In some cases, the establishment of standards has been worked out through private negotiation or left to market forces (Langlois and Robertson 1995). A number of the smaller automobile producers in the United States, for example, voluntarily agreed early in the twentieth century to standardise simple parts in order to achieve economies of scale without putting severe constraints on design (G. V. Thompson 1954). The standardisation of railway gauges in the south of England likewise occurred without government intervention when the directors of the Great Western Railway were eventually forced to agree that compatibility with adjacent lines was of more value than the technical benefits offered by Brunel’s broad gauge. In fact, it is probably legitimate to generalise by saying that standardisation will almost always take place eventually whenever significant network externalities are present.

But ‘eventually’ may not be soon enough, in that good opportunities may be discouraged for prolonged periods or abandoned altogether if a system is fragmented. As David (1991) has shown, the diffusion of a truly systemic set of innovations, such as those associated with electrification, may take many decades. Although almost all potential users may be brought on board in the long run, there may be losses over shorter periods as problem-holders who might benefit from early access to the system fail to make contact with solution-holders. An additional, and quite opposite, problem with privately arranged standardisation is that users may be locked into a sub-optimal system if standardisation occurs too soon or is pushed through by powerful operators who stand to gain from the adoption of a technically deficient system. An example is the adoption of the 115 volt standard for most domestic and commercial electricity in the United States because early light bulb filaments wore out uneconomically quickly when higher voltages were used.

These shortcomings in what may be termed ‘standardisation by consensus’ would seem to provide an opening for governments to use their power to impose standards as a way of accelerating the diffusion and adoption of innovations. In practice, this sort of standardisation appears to be most common in the cases of public utilities and industries, such as communications, that have the ability to influence such public values as voting behaviour. Even in countries like the US and Australia, which have long possessed substantial privately owned broadcast networks, governments have insisted on deciding upon and allocating broadcast frequencies, in part to avoid interference which private stations that are located close to each other might cause by broadcasting on similar frequencies. More recently, governments attempted to speed up innovation by imposing standards for colour television and high-density television (HDTV) before systems became widespread in order to ensure that network externalities would be large enough to encourage large numbers of users to join the network. Finally, governments have even intervened, albeit infrequently, to change standards when advances in technical knowledge have indicated that the earlier standard was inefficient. Following the Second World War, for instance, the United States government changed the frequency band allocated to FM radio broadcasts because technical advances during the war had shed doubt on the technical efficiency of using the original band (Sterling 1968).7

The imposition of government standards, however, is no guarantee of uniformity or efficiency. The railway system in Australia provides an extreme example in that the gauges were all set by the various colonial governments before Federation in 1901. As one of the aims of each colony was to try to keep as much traffic as possible within its own borders,8 the colonies deliberately chose different gauges. Even partial reconciliation took decades to achieve. Similarly, because colour television was commercialised earlier in the US than elsewhere, the standard imposed by the government turned out to be an inferior technology, in much the same way as early standardisation through private agreements has sometimes led to the adoption of systems that have later turned out to be inefficient.

In general, governments may indeed speed up innovation by adopting and enforcing standards, but this is probably most appropriate for very large systems and even then may lead to error. Private negotiation over standards seems more appropriate for the multitude of decisions affecting smaller groups who are better informed of their own needs than government agents are likely ever to be unless substantial sums of public funds are invested in educating them in the minutiae of other people’s business (Hayek 1937, 1945). On an intermediate level of aggregation, either governments or private interests may work out standards. Culturally, continental European nations, with a long tradition of guild regulations, seem more favourably inclined towards imposed standards than are most English-speaking countries. It remains to be seen if, in practice, rates of innovation will accelerate or the welfare of citizens of the European Union will be increased by the imposition of ‘Euro-standards’ for beer, bread, condoms and other common goods for which there is often diversity in individual tastes and needs.

Accelerating diffusion and increasing absorptive capacity

Two areas in which government innovation policy has attempted to improve upon informal communication processes for several centuries are (1) the direct diffusion of innovation and (2) the generation of more conducive environments for the acceptance of innovation. One of the main features of the Mercantilist regulations enacted in most European nations in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries was the encouragement of labour skills and innovative production processes. These policies were often coupled with others intended to reduce skills among foreign populations and prevent other nations from themselves gaining access to new techniques. Although most of the more severe policies, such as those prohibiting the emigration of skilled workers and the export of machinery, had been repealed across Europe by the late nineteenth century, support for domestic industry has remained a policy tenet in most countries at all stages of development.

Many of the more important features of Mercantilism, including tariffs, quantitative restrictions on imports and navigation acts, are aspects of industry policy that are outside the scope of this chapter. Policies involving the direct diffusion of innovation and the creation of a conducive environment for change, however, can be viewed profitably in terms of our model of the communication process. In particular, both types of policy involve education in order to improve understanding, but on different levels of generality. Attempts to improve the diffusion of particular innovations may entail relatively specific instruction in a narrow range of skills, whereas a much broader form of education is needed to improve receptiveness to changes in the general environment.

Direct intervention by governments to promote innovation can be used as a way of economising on scarce communications skills. If there is a shortage of people in the population who are capable of sending out the right questions or of understanding and acting upon the answers, then the government may itself recruit a corps of experts to reduce noise by providing direct control over innovation policy. As in Meiji Japan or some of the German states in the nineteenth century, the government can take the lead in the collection of information and the training of skilled workers. Investment funds may also be directed into designated sectors rather than decisions being left to private investors, and, at the limit, ownership and management may even be placed in public hands.9 Nevertheless, there are limits to how much actual direction can be imposed from above. Certain practices cannot be dictated either because they are tacit, and therefore unteachable, or because they involve the adaptation of imported techniques and need to be worked out initially by trial and error.

Hence if an innovation policy is successful, in the sense that it takes root and spreads seedlings, the need for government action should recede as skills and attitudes learnt originally in pilot projects become more generalised. Indeed, although businesses may continue to lobby for government assistance in such forms as tariffs, they will often become sceptical about the allegedly superior acumen of government functionaries. For example, a recent paper on the European computer industry complained that, despite attempts by the EC (as it then was) to foster co-operation on computer development among firms in member countries, these firms generally looked to co-operation with American or Japanese computer manufacturers for technical advances (Mytelka 1992). In practice, though, the behaviour of the firms seems rational: why should they devote their resources to communicating with other backward firms when they can enter into joint ventures or other arrangements with foreign firms that can offer some insight into the most advanced technologies?

On a more general level, perhaps the most important aspect of innovation policy that a government can undertake is in increasing the ability of a nation’s people to understand and initiate innovations and to imitate and improve upon innovations that originated elsewhere. In two influential articles, Cohen and Levinthal (1989, 1990) have emphasised the importance of what they term an organisation’s ‘absorptive capacity’.10 Absorptive capacity refers to the ability of an organisation to recognise and act upon information that might be competitively useful. On the corporate level, this entails developing a knowledge of technologies that lie beyond the current practices of a particular firm so that the firm can quickly take advantage of relevant new developments in other sectors. The premise is that, while firms may lose to a degree in that some of their absorptive capacity may never be needed in practice, they will gain overall because they will be better placed competitively owing to their ability to respond swiftly to change. Related to this is Stiglitz’s proposition that learning in itself enhances an organisation’s ability to learn (Stiglitz 1987). Thus firms that maintain a strong and active interest in new concepts should in general be able to generate and implement change more rapidly than firms that narrowly restrict their attention to their own current technologies.

On an aggregative level, absorptive capacity translates into educating the population up to a high level in both theoretical and practical subjects. If a nation’s economy is to be flexible and able to respond quickly to change, then education must be provided ahead of demand and it cannot be limited to topics of current interest. This, of course, injects an element of uncertainty into curriculum design, just as research and development projects will always be uncertain to the extent that outcomes cannot be accurately predicted. Nevertheless, experience from both the past and the present supports the proposition that countries that have high levels of education and cultures that place a high intrinsic value on learning are likely to be more successful at innovation. This is illustrated by the relative success in recent decades of the Asian Tigers in comparison to Latin American countries that initially had similar levels of per capita income, and also by the growth trajectories of nations such as the United Kingdom, Germany, the United States and Switzerland after 1850.

It is arguable, for example, that one of the major reasons for the relative retardation of the British economy that began in the late Victorian and Edwardian periods is that the country lacked absorptive capacity to cope successfully with the major innovations of the era. In particular, British firms in general were in an inferior position to appropriate benefits from many branches of the developing electrical and chemical industries than were firms in countries that had already created systems of technical education because these industries required significant inputs of technically trained labour. In Germany, Switzerland and the US, governments recognised that technical education was a public good and subsidised it heavily, but in Britain the subsidies were smaller, and employers and potential students were unwilling to make up the difference through private payments (Robertson 1981). British firms depended instead on their deep stocks of skilled labour, but this confirmed their reliance on manual skills at a time when several important industries were making a transition to more highly technical job routines.11 In the meanwhile, nations with better developed technical education facilities jumped to new technological trajectories where they were able to learn new routines rapidly and to seize market share before British firms could again become meaningful competitors. In the terms of the model of the communication process shown in Figure 14.2, by investing early in techniques for encoding and decoding technological information, the Germans, the Swiss and the Americans had reduced noise levels significantly even before important messages began to be transmitted. The British, by contrast, had to cope with noise much longer, which severely reduced their initial absorptive capacity.

Information, communication and investment

Whenever investment in innovation activities is deterred by a scarcity of information, as Richardson shows can happen, government policies may offer effective ways of improving the flows of information to individual investors, thereby increasing the overall rate of innovation. Government policy can be useful in several respects. When there is a high degree of uncertainty, governments can help to reduce the effects by providing guarantees or safety nets for innovators. These policies, which are not discussed in detail here, include ways of reducing competition for innovators or assuring markets. This can be accomplished through many common policies, such as tariff protection, direct subsidies and promises by government departments to buy only locally produced goods. As an extreme position, governments may guarantee revenues to innovative firms in the early stages of production.

Where the problem is ignorance rather than uncertainty, government policies may take different forms to improve information flows and thus make investment more attractive. In some cases, governments may encourage policies of discovery, such as promoting research and development or sending representatives to report on conditions in foreign countries. Our emphasis here, however, has been on enhancements to the communication process in which governments institute policies to spread information directly, attempt to improve information flows by providing channels of communication, or work to reduce noise through improvements in encoding and decoding.

But the fact that governments are capable of filling these roles does not mean that they are the most efficient agents. In some cases, entrepreneurial alertness may provide a superior private alternative to government action.12 Moreover, unless governments are going to undertake detailed investment plans themselves, most policies to reduce noise do, in fact, operate by making alertness easier and thus improving the quality of private investment decisions. The maintenance of high levels of absorptive capacity in the nation as a whole, however, remains a very important responsibility for governments if the nation is to achieve the flexibility necessary to keep apace of rapid changes in technology. And, as Nelson (1993) and his co-authors have shown, government activities occupy important, even if not dominant, positions in many national systems of innovation.

It is important to remember, however, that private investment channels are highly heterogeneous and may therefore need different types of government policies to deal with their particular problems. One of the most important distinctions, to which I will turn in the next two section, is between the requirements of firms that concentrate on innovative activities and those of firms in mature industries that may be strongly affected by innovation after extended periods of quiescence.

INFORMATION, SIMILARITY AND COMPLEMENTARITY

Innovation and organisational form

The information needs of firms in ‘new’ industries may differ substantially from those of firms in ‘mature’ industries. New industries are characterised by rapid rates of product or process innovation,13 but these decrease as dominant technologies are chosen. Because they compete in such unstable environments, firms in new industries (which, for brevity, I call innovative firms) have very substantial information needs that place strains on communication networks. Survival requires innovative firms to gain quick access to information derived elsewhere, while they frequently wish also to have exclusive access to information that they have developed in-house. In practice, it may prove difficult for such firms both to tap outside sources and to maintain confidentiality themselves because other firms are reluctant to give up information when there is no reciprocity. Furthermore, exchanges of employees, which are common among innovative firms in places such as Silicon Valley, make it hard for firms to retain proprietary access to information for very long.

Popular recommendations as to the organisational forms required to provide for the information needs of innovative firms fall into two main categories.14 The first centres around the ideas of the economist Michael Piore and a number of sympathisers from other disciplines, including Charles Sabel, AnnaLee Saxenian, Michael Best and Jonathan Zeitlin (Piore and Sabel 1984; Sabel 1989; Sabel and Zeitlin 1985; Saxenian 1994; Best 1990). The basic theme of their arguments is that firms are more likely to be innovative in industrial districts in which there are concentrations of small producers in close proximity who, intentionally or not, share ideas readily. As a result, firms are able to size up initiatives by their competitors very early in the game and to react equally quickly. In some cases, as in Silicon Valley, these firms may concentrate on industries in the early stages of innovation, but firms in other industrial districts, such as the Third Italy (the provinces of Emilia-Romagna and Tuscany), have reached more mature stages of development.

Real or putative network structures, like those in Silicon Valley and along Route 128, have become very popular among academics in recent years.15 Saxenian provides a good summary of the benefits of industrial districts when they function at their best:

Geographic proximity promotes the repeated interaction and mutual trust needed to sustain collaboration and to speed the continual recombination of technology and skill. When production is embedded in these regional social structures and institutions, firms compete by translating local knowledge and relationships into innovative products and services; and industrial specialization becomes a source of flexibility rather than of atomism and fragmentation.

… When technology remained relatively stable over time, vertical integration and corporate centralisation offered needed scale economies and market control. In an age of volatile technologies and markets, however, the horizontal coordination provided by interfirm networks enables firms to retain the focus and flexibility needed for continuous innovation.

(Saxenian 1994: 161–2)

Other authors have reached the opposite conclusion based on much the same evidence. The most vocal proponent of centralisation is William Lazonick (1991). Drawing on the works of Chandler, Schumpeter, Marshall and Marx, Lazonick has concluded that markets are inefficient in providing the necessary co-ordination for successful and continuous innovation (especially systemic innovation) and that change can best be promoted by large integrated firms. Although Lazonick does not specify his vision very closely, he appears to advocate Japanese keiretsu organisations, or perhaps diversified and vertically integrated Chandlerian firms, as the most efficient agents of innovation.16

Should innovation be internalised?

These various theories, which are sometimes presented as near panaceas, appear to support different forms of industry policy. If one believes in the adaptive ability of small firms, then strict antitrust laws are required to prevent the growth of stultifying monsters. Belief in the innovative powers of vertically integrated giants and in the inadequacy of markets, however, should lead to calls for the repeal, or at least the watering-down, of antitrust legislation.

But the choice of an appropriate policy to promote innovation is in reality far more difficult because the authors that are cited have supported their views with examples from different innovative contexts. Saxenian believes that technology has entered a period of permanent revolution in which important industries will undergo continual significant changes. In essence, she is arguing that these new technologies will not offer important economies of scale and that, because product technologies will be in a state of continual flux, process technologies will never become the dominant concern, as they are in the Abernathy–Utterback model (Abernathy and Utterback 1978). Piore, Sabel, Best and Zeitlin, however, put primary emphasis on industries with limited economies of scale that have already settled most of their major technological problems and are now concerned with incremental innovation. Lazonick’s argument, finally, is that large firms can best undergo continuous major change by internalising the sources of innovation, which permits them to maintain economies of scale while remaining at the forefront of their industries. Indeed, like Smith (1976), Stigler (1951) or Rosenberg (1963), Lazonick sees new industries as arising out of old ones; unlike the others, however, Lazonick maintains that the new industries should not be spun off, but should, rather, remain within large firms in which diversity feeds on itself.

Concepts developed by G. B. Richardson in ‘The organisation of industry’ (1972) provide tools for examining these different contentions. Richardson divides the activities undertaken in an industry into those that are similar to the core activities of a firm because they draw on the same capabilities as do the core activities and those that are complementary because, while they are needed for the final product, they draw on different capabilities. If firms are viewed as bundles of capabilities that function best when they draw on the same types of skills, then any given firm will be inclined to internalise similar activities but leave the performance of complementary activities to other firms with more appropriate capabilities. We might ask, therefore, when innovative activities are likely to be similar and when they are likely to be complementary to a firm’s core activities.

Industrial districts, whether those described by Marshall (1890) or those in modern Italy, are characterised by high levels of vertical as well as horizontal disintegration. That is, firms are not only relatively small, but they are also highly specialised. This implies that there are few similar activities at any stage of the production process and (also or alternatively) that there are no important transaction costs.17 When there are many similar activities, however, even small firms may choose to be highly vertically integrated despite limited economies of scale and low transaction costs. Furthermore, the presence of economies of scale or transaction costs encourages horizontal or vertical integration, respectively.

Given the number of complications involved, it is not surprising that the question of whether an innovation is best developed internally or externally in any particular case is more empirical than theoretical. When an innovation affects an activity that is similar to one already undertaken by a firm, then the firm might well find it advantageous to internalise the operations associated with that activity. Because they build on existing activities, such innovations are incremental. When an innovation leads to the replacement of an existing similar activity, however, the picture changes. Even though the result might be incremental in scope if the dislodged activity was of minor importance, it is less likely that the firm would have a comparative advantage in internalising the innovation. In such a situation, when the innovation involves complementary rather than similar activities, a firm might begin to outsource the new version of a component that it had previously produced itself.18 When the innovation affects an activity that is currently complementary, the result is again indeterminate. If the innovation confirms the distinctiveness of the complementary activity, then the innovation would not lead to internalisation, but if an innovation to a component that is presently complementarily causes the production of that component to draw more heavily on capabilities similar to the core capabilities of a firm, then the outcome could be increased vertical integration.19 As radical innovations are most commonly complementary, both their development and subsequent production are likely to be external to a firm producing the original good.

Because innovations may be either similar or complementary to the existing activities of a firm and because they may be expected to be developed either internally or externally, depending on, among other factors, the degree of radicalness of the innovation and its relationship to the current activities of the firm, no set of government policies towards firm size or diversity appears to be justified. Large and small firms as well as specialised or diversified firms can all produce important innovations if overall conditions are favourable.20

INNOVATION AND INDUSTRY MATURITY

It is now widely documented that firms in mature industries find it very difficult to cope successfully with major technological shifts. Although life-cycle analysis allows for incremental change to continue virtually indefinitely, more basic changes are frequently handled poorly by established firms (Henderson and Clark 1990; Iansiti 1995). Some existing firms do not even attempt to assimilate important new technologies, but the rate of success is low among those that do (Utterback 1994). As a result, changes in technological trajectories usually lead to a shake-up in industry structure, with new firms replacing many of the former leaders.

J. A. Schumpeter (1950) calls this process ‘creative destruction’, but he also notes that large established firms may have an advantage in generating innovations. Several more recent writers on management have likewise been rather optimistic concerning the fate of established companies. Charles Baden-Fuller and John M. Stopford (1992), for example, have written on ways of Rejuvenating the Mature Business and James M. Utterback (1994) contends that mature firms can survive technological transformations by Mastering the Dynamics of Innovation. Nevertheless, there is considerable evidence that existing firms are not always the most efficient institutions to master new technologies. As Schumpeter realised, governments are therefore faced with an unpleasant policy choice. At any given time, established firms dominate a modern industrial economy in terms of value of output. Moreover, they tend, both on average and collectively, to be larger in both the numbers of employees and the amount of funds invested than are firms dedicated to exploiting new technologies. Both the employees and investors of established firms are also voters and they have legitimate reasons for fearing innovations that will threaten their jobs and assets. Innovative firms, however, although small and unstable, have higher growth rates and promise better long-term benefits for the economy.

How, then, should governments respond to innovation? Should they oppose innovation because it is disruptive, or should they embrace it because of its promise of future prosperity? Saxenian (1994) seems to have few doubts concerning the proper course to follow. To her, large firms are dinosaurs that are to be replaced by smaller and more agile firms. She favourably portrays Silicon Valley as a land of (to my use own term) ‘throw-away firms’. There, she tells us, entrepreneurs can easily start up firms to exploit new concepts. If the firms fail, as many do, the entrepreneurs suffer little stigma and can soon find high-paying jobs with their erstwhile competitors. Utterback (1994) takes the opposing position, that established firms should be saved rather than replaced. He feels that policies should be directed towards increasing the flexibility of existing companies.

Once again, the answer depends on a more detailed consideration of the nature of the innovation in question and its relationship to the capabilities of existing firms. In some cases, radical innovation does indeed upset an industry so severely that it virtually ceases to exist and is replaced by a new industry. For example, automobiles, railways and electric trams eventually displaced horse-drawn forms of transportation altogether. Although some companies may have continued to exist in other lines of business, the older technology left no important vestiges (except, perhaps, for a common reliance on the wheel).21 The new technologies were, to use the term of Tushman and Anderson (1986), competence-destroying. Or, to adapt Richardson’s (1960) term, the importance of the similar activities across technologies was not sufficiently great to allow the new technology to be grafted on to the old organisational structures. This failure to adapt was reinforced by the ways in which routines (Nelson and Winter 1982) and other aspects of organisational culture often make existing firms actively resistant to the adoption of new technologies whose use involves practices that are orthogonal to the prevailing practices of the organisation.

One of the most important aspects of the failure of established firms to adapt to innovation is that they tend to narrow down their channels of communication as they mature. The paradigm that underlies a technological trajectory can be conceived of as a set of behavioural patterns. In the words of Dosi, a technological paradigm is ‘an “outlook”, a set of procedures and definitions of the “relevant” problems and of the specific knowledge related to their solution’ (Dosi 1982: 148). Once firms achieve sustained success with a particular paradigm they tend to reduce their absorptive capacity to encompass only activities that are related to that paradigm. As Pavitt has noted:

Firms do not ‘search’ for innovations in a general ‘pool’ or ‘stock’ of knowledge, all of which is equally accessible and assimilable by them. Instead, they search in zones that are closely related to their existing skills and technologies. What firms can hope to do in technology and innovation in the future is strongly conditioned by what they have been able to do in the past.

(Pavitt 1986: 174)

If the aim of policy is to allow established firms to deal successfully with innovation, then the remedies suggested above (see the subsection ‘Accelerating diffusion and increasing absorptive capacity’, pp. 271–4) will be helpful in increasing their absorptive capacity. But, as Dosi (1982), Nelson and Winter (1982) and others have suggested, the behavioural patterns of established firms in mature industries go well beyond tone deafness when innovations are broadcast. The routines of such firms are focused finely on doing well what they already do, and this often introduces an element of inflexibility even when the firms are aware of the challenges posed by innovations. Information alone is not sufficient to bring about successful change. The problems of established firms often appear at the implementation rather than at the planning stage because the new technologies may involve activities, practices and capabilities that run counter to those that the firm has long used successfully.

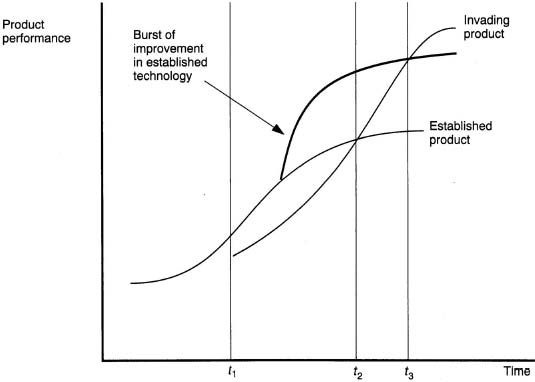

This raises a very real dilemma for policy-makers because it is not at all clear that governments can do anything to bring about a rapid displacement of micro-behaviour that is not conducive to change. Utterback (1994) regrets the fact that established firms tend to respond to radical innovation by perfecting their existing technologies. When they do chase perfection, as illustrated in Figure 14.3, the ‘product performance’ of existing technologies remains above that of newer technologies for a substantial period because the former are still being improved and bugs are still being worked out of the latter.22 Utterback recommends that established firms immediately adopt new technologies rather than continue to tinker with existing ones so that they can go down the learning curves of the innovative technologies as rapidly as possible and thus (it is hoped) retain leadership following the transition.

Stoneman and Diederen, however, are concerned that some policies may lead to rates of diffusion that are excessive. They advocate (although they do not outline) policies that are ‘aimed at fine tuning the speed of diffusion’ (Stoneman and Diederen 1994: 928) As they explain:

Figure 14.3 Performance of an established and an invading product: burst of improvement in established product

Source: Utterback 1994: 160

The idea of too fast a rate of diffusion for an economy often causes some consternation amongst policy makers for whom the principle that new technology should be introduced as quickly as possible is almost a statement of faith (usually on the grounds that use of new technology will increase competitiveness). However, in the absence of significant differences between private and social costs and benefits, a rate of diffusion that is too fast could result in firms adopting a technology before it has become profitable to do so or adopting a less well developed or higher priced technology today at the expense of adopting a more developed or cheaper technology in the future.

(Stoneman and Diederen 1994: 919)

It is difficult to conceive of the criteria that might, in practice, underpin a policy of fine-tuning the speed of diffusion. One category of fears that Stoneman and Diederen voice concerns inherent uncertainty. It is clear that firms and whole societies have become locked into inferior technologies in the past, but if policy-makers refuse to sanction the adoption of an innovation on the grounds that a better technology may someday come along, they could wait forever. Even if they do delay early adoption and then choose a superior technology, the nation may not benefit. By the time nation X acts, other important countries may be locked into an inferior technology that is incompatible. As a result, despite its ‘better’ decision, nation X could be shut out of potential export markets and face isolation.

A second problem arises from defining premature adoption in terms of low initial profitability. As Figure 14.3 illustrates, in its initial stages an innovation may not perform well because complementary assets, including knowledge, have not yet been developed. In time, however, these problems are overcome, giving pioneer adopters a valuable shove down their experience curves. Therefore, it may often be more reasonable to think of the low initial profits as arising out of an investment in learning rather than as a sign that the technology is not yet ready to be adopted. If subsequent adopters have to make similar investments in learning, the pioneers will have gained a competitive advantage that latecomers may find it hard to erase.23

CONCLUSION

This chapter discusses ways of improving the availability of relevant information to firms undertaking investment decisions, a problem highlighted in a somewhat different context by George Richardson (1960). All the evidence set out above points towards the difficulty of making policies that will improve information and lead to better investment decisions. Communications can certainly be enhanced in order to give potential investors access to better information, but action on the micro level is difficult to achieve because it presupposes that policy-makers themselves have absorbed heroic amounts of information about the needs of individual firms and industries. Policies designed to improve the absorptive capacity of society as a whole through better education are more feasible, however, and are likely to pay off well in social welfare terms.

By the same token, the use of government policy to influence firm organisation would require detailed knowledge of specific problems, since different types of innovation are likely to benefit from different types of firm and industry structure. Richardson’s (1972) important distinction between similar and complementary activities has been employed to argue that innovations that depend heavily on activities similar to those fostered by the existing capabilities of a given firm might well be developed and implemented internally. When complementary capabilities are involved, innovation is often better left to outside suppliers.

Finally, firms in mature industries may or may not need help to allow them to assimilate radical innovations. Although Utterback is only one of many management writers who believes that it is desirable for innovations to be implemented by established firms rather than ceded to firms from outside an industry,24 there is a great deal of evidence that many successful firms are highly inflexible. Contrary to Utterback’s position, the situation shown in Figure 14.3 may be the best one for society. The threat of a superior competing technology pushes once complacent established firms to higher levels of productivity using the current technology while other firms that have adopted the innovative technology are still learning the routines and establishing the complementary assets needed to profit from it. In the end, the new firms with appropriate routines survive, while the older, inflexible firms die or find something else to do (Robertson and Langlois 1994). This may involve heavy social cost, but the alternative – to place barriers in the way of innovation – could be more costly in the long run.

The fact that this analysis offers no positive recommendations for government policy does not mean, however, that it lacks operational value. The same principles that underlie the policy discussion above provide guidelines appropriate for the strategy decisions of individual firms. If firms maintain high levels of absorptive capacity, concentrate on similar activities and resist the temptation to enter into activities for which their existing routines are unsuitable, they are likely to benefit.25

NOTES

1 Most of what Clark terms ‘uncertainty’ is, in fact, ‘ignorance’ in the terminology adopted here.

2 As Stinchcombe) points out, the sources of ‘news’ exist in ‘distinct social locations’ (Stinchcombe 1990: 4; italics in original), and the same is true of potential recipients. What is needed is a sort of Yellow Pages directory combined with a street map that allows those who are unfamiliar with the terrain to find strange locations.

3 An examination of the positive, strategic role that spillovers may play is given by Langlois and Robertson (1996).

4 To be more precise, solution-holders should be willing to accept reductions in profits in some markets up to the point at which this erosion is just matched by gains from allowing producers in other markets to use the solution.

5 If there has been a shift in technological trajectory or paradigm this may be ‘old news’.

6 Similar figures may be found in many elementary management books.

7 This was a courageous decision in that it rendered obsolete all existing FM broadcasting and receiving equipment. But without being too cynical, it is possible to wonder if the same decision would have been made if the existing network had not been comparatively small.

8 For example, although Melbourne in Victoria is a more natural port than Sydney for the export of grain from the Riverina region of southern New South Wales, the New South Wales government used its control over gauges within the colony to direct traffic from the Riverina to Sydney by imposing the extra expense on shippers to Melbourne of breaking the journey and shifting goods from one set of railway wagons to another at Albury on the New South Wales–Victoria border.

9 For his views on planning versus market co-ordination, including a highly sceptical analysis of indicative planning, see Richardson (1971).

10 See also Mowery and Rosenberg (1989).

11 Richardson’s distinction between similar and complementary activities (Richardson 1972) helps to explain why education is generally done in specialised institutions while the acquisition of skills is best undertaken by firms. Training in skills is a by-product of the everyday activities of firms. This is especially true, of course, of skills that are peculiar to a particular firm. Instruction in broader knowledge, on the other hand, frequently draws on routines outside the normal activities of commercial concerns and may, in fact, call on behaviour (such as questioning the person in charge) that contradicts the behaviour that a firm wants to instil in its workers. As a result, education is generally assigned to specialised institutions that are appropriate for instruction in theoretical fields but ill equipped to undertake complementary training in skills.

12 Weder and Grubel (1993) argue that certain types of private institutions, such as trade associations, industry clusters and conglomerate firm structures, may also act as agents to spread knowledge of innovations while allowing the returns to be internalised.

13 There are several life-cycle models that relate maturity to rates of change in other variables. One of the most popular, that of Abernathy and Utterback (1978), contends that the rate of product innovation is very high in new industries but slows down in mature industries. The rate of process innovation lags behind that of product innovation but it also slows down with maturity.

14 For a fuller discussion of the organisational needs of innovative firms, see Robertson and Langlois (1995).

15 See, for example, the articles in Nohria and Eccles (1992).

16 Lazonick’s ideas (like those of Piore and Sabel and Best) are underpinned by theories of labour management. Lazonick’s 1990 and 1991 books should be read together to get a better, if highly discursive, insight into his general argument. Florida and Kenney (1990) use theories of organisational behaviour to support an argument similar to Lazonick’s in their advocacy of large vertically integrated firms in the United States to overcome Japanese competitiveness. Starting from a Coasean standpoint, Weder and Grubel (1993) find support for the prescriptions both of Lazonick and Piore, and of Sabel and Best.

17 By undertaking similar activities, firms should be able, through economies of scope, to reduce direct costs of production by sharing equipment or skills. Transaction costs, however, refer to the costs of using markets. When transaction costs are substantial, firms may find it cheaper to internalise complementary activities as well.

18 The result could be an increase in modularisation. See Langlois and Robertson (1992).

19 If the firm maintains absorptive capacity in the form of wide-ranging research capabilities, this would be more likely to lead to an increase the number of similar activities than if the absorptive capacity takes the more passive form of aiming for an ability to recognise useful innovations rather than to develop them internally. When the range of fields in which relevant innovations could be developed is a large one a passive stance would probably be a more cost-effective research strategy. In either case, however, similarity in research does not necessarily imply similarity in production capabilities, and a firm may wish to license or otherwise spin off its discoveries that are complementary at the production stage. See, for example, the account in Langlois and Robertson (1989) of how the Ford Motor Company developed designs of machinery for its production line that it then, after the prototype stage, turned over to more conventional machine tool companies.

20 This conclusion is fortified, of course, by the inevitable presence of uncertainty in the innovation process, as a result of which innovations might in fact come from sources that, in an a priori analysis, seem highly improbable.

21 But close complementarity did permit some firms that used horses to make the transition to motor vehicles, e.g. the British removal company Pickfords.

22 For a similar analysis using experience curves, see Robertson and Langlois (1994).

23 The views of Stoneman and Diederen are very similar to the attitudes of ‘excessive rationality’ that are alleged to have led to the relative decline of the British economy after 1870. For a comparative discussion of British, German and American attitudes towards investment and innovation before 1914, see Pollard and Robertson (1979: Introduction).

24 Although Utterback and other writers are certainly sincere, it is worth pointing out that it is much easier to get people to pay attention to (and pay for) ideas that offer them, or their organisations, hope than to ideas that recommend that they be subjected to lingering deaths or euthanasia.

25 There is controversy in the resource-based school of strategy about the extent to which firms should concentrate on developing activities based on their existing capabilities (i.e. concentrate on similar activities) (Kay 1993) and whether firms should develop new capabilities and thus become more flexible in dealing with innovation (Hamel and Prahalad 1989; Prahalad and Hamel 1990). The arguments developed here suggest that Kay is correct in assessing the ability of firms to adjust to radical innovation, but that the policies of Prahalad and Hamel (which are related to suggestions that absorptive capacity be increased) would be of use in adapting better to incremental innovations.

Abernathy, W. and Utterback, J. M. (1978) ‘Patterns of industrial innovation’, Technology Review 80(7): 40–7.

Baden-Fuller, C. and Stopford, J. M. (1992) Rejuvenating the Mature Business: The Competitive Challenge, London: Routledge.

Best, M. (1990) The New Competition: Institutions of Industrial Restructuring, Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Chandler, A. D., Jr (1962) Strategy and Structure: Chapters in the History of Industrial Enterprise, Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

Clark, K. B. (1985) ‘The Interaction of Design Hierarchies and Market Concepts in Technological Evolution’, Research Policy 14: 235–51.

Cohen, W. M. and Levinthal, D. A. (1989) ‘Innovation and learning: the two faces of R&D’, Economic Journal 99: 569–96.

—— (1990) ‘Absorptive capacity: a new perspective on learning and innovation’, Administrative Science Quarterly 35: 128–52.

David. P. A. (1991) ‘Computer and dynamo. The modern productivity paradox in a not-too-distant mirror’, Technology and Productivity: The Challenge for Economic Policy, Paris: OECD.

Davies, P. (1995) The Cosmic Blueprint: Order and Complexity at the Edge of Chaos, London: Penguin. (Originally published in 1987.)

Dosi, G. (1982) ‘Technological paradigms and technological trajectories: a suggested interpretation of the determinants and directions of technical change’, Research Policy 11: 147–62.

Florida, R. and Kenney, M. (1990) The Breakthrough Illusion: Corporate America’s Failure to Move from Innovation to Mass Production, New York: Basic Books.

Grossman, G. M. and Helpman, E. (1991) ‘Trade, knowledge spillovers, and growth’, European Economic Review 35: 517–26.

Hamel, G. and Prahalad, C. K. (1989) ‘Strategic intent’, Harvard Business Review (May-June): 63–76.

Hayek, F. A. von (1937) ‘Economics and knowledge’, Economica NS 4: 33–54.

—— (1945) ‘The use of knowledge in society’, American Economic Review 35: 519–30.

Henderson, R. M. and Clark, K. B. (1990) ‘Architectural innovation: the reconfiguration of existing product technologies and the failure of established firms’, Administrative Science Quarterly 35: 9–30.

Iansiti, M. (1995) ‘Technology integration: managing technological evolution in a complex environment’, Research Policy 24: 521–42.

Kay, J. (1993) Foundations of Corporate Success: How Business Strategies Add Value, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kirzner, I. M. (1973) Competition and Entrepreneurship, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Langlois, R. N. and Robertson, P. L. (1989) ‘Explaining vertical integration: lessons from the American automobile industry’, Journal of Economic History 49: 361–75.

—— (1992) ‘Networks and innovation in a modular system: lessons from the microcomputer and stereo component industries’, Research Policy 21(4): 297–313.

—— (1995) Firms, Markets and Economic Change: A Dynamic Theory of Business Institutions, London: Routledge.

—— (1996) ‘Stop crying over spilt knowledge: a critical look at the theory of spillovers and technical change’, paper presented to the MERIT Conference on Innovation, Evolution and Technology, August 25–27, Maastricht, the Netherlands.

Lazonick, W. (1990) Competitive Advantage on the Shop Floor, Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

—— (1991) Business Organization and the Myth of the Market Economy, New York: Cambridge University Press.

Marshall, A. (1890) Principles of Economic Growth, London: Macmillan.

Metcalfe, J. S. (1994) ‘Evolutionary Economics and Technology Policy’, Economic Journal 104: 931–44.

Mowery, D. C. and Rosenberg, N. (1989) Technology and the Pursuit of Economic Growth, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Mytelka, L. K. (1992) ‘Dancing with wolves: global oligopolies and strategic partnerships’, paper presented to the Conference on Convergence and Divergence in Economic Growth and Technical Change: Maastricht Revisited’, December 10–12, Maastricht, The Netherlands.

Nelson, R. R. (ed.) (1993) National Innovation Systems: A Comparative Analysis, New York: Oxford University Press.

Nelson, R. R. and Winter, S. G. (1982) An Evolutionary Theory of Economic Change, Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Nohria, N. and Eccles, R. G. (1992) Networks and Organizations: Structure, Form, and Action, Boston, Mass.: Harvard Business School Press.

Pavitt, K. (1986) ‘Technology, innovation and strategic management’, in J. McGee and H. Thomas (eds) Strategic Management Research: A European Perspective, Chichester: Wiley.

Piore, M. J. and Sabel, C F. (1984) The Second Industrial Divide, New York: Basic Books.

Pollard, S. and Robertson, P. (1979) The British Shipbuilding Industry, 1870–1914, Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Prahalad, C. K. and Hamel, G. (1990) ‘The core competence of the corporation’, Harvard Business Review 68(3):79–91.

Richardson, G. B. (1960) Information and Investment: A Study in the Working Of the Competitive Economy, Oxford: Clarendon Press.

—— (1971) ‘Planning versus competition’, Soviet Studies 22(3): 433–7; reprinted as Annex II in G. B. Richardson (1990).

—— (1972) ‘The organisation of industry’, Economic Journal 82: 883–96.

—— (1990) Information and Investment: A Study in the Working Of the Competitive Economy, 2nd edn, Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Robertson, P. L. (1981) ‘Employers and engineering education in Britain and the United States, 1890–1914’, Business History 23: 42–58.

Robertson, P. L. and Langlois, R. N. (1994) ‘Institutions, inertia and changing industrial leadership’, Industrial and Corporate Change 3(2): 359–78.

—— (1995) ‘Innovation, networks, and vertical integration’, Research Policy 24: 543–62.

Romer, P. M. (1990) ‘Endogenous technological change’, Journal of Political Economy 98(5), part 2: S71–S102.

Rosenberg, N. (1963) ‘Technological Change in the Machine Tool Industry, 1840–1910’ Journal of Economic History 23(2): 414–43.

Sabel, C. F. (1989) ‘Flexible specialization and the re-emergence of regional economies’, in P. Hirst and J. Zeitlin (eds) Reversing Industrial Decline? Industrial Structure and Policy in Britain and Her Competitors, Oxford: Berg.

Sabel, C. F. and Zeitlin, J. (1985) ‘Historical alternatives to mass production: politics, markets, and technology in nineteenth-century industrialization’, Past and Present 108: 133–76.

Saxenian, A. (1994) Regional Advantage: Culture and Competition in Silicon Valley and Route 128, Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Schumpeter, J. A. (1950) Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy, New York: Harper.

Smith, A. (1976) The Wealth of Nations, Glasgow edition, Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Sterling, C. H. (1968) ‘WTMJ-FM: a case study in the development of broadcasting’, Journal of Broadcasting 12(4): 341–52; reprinted in L. W. Lichty and M. C. Topping (eds) American Broadcasting: A Source Book on the History of Radio and Television, New York: Hastings House.

Stigler, G. J. (1951) ‘The division of labor is limited by the extent of the market’, Journal of Political Economy 59(3): 185–93.

Stiglitz, J. E. (1987) ‘Learning to learn, localized learning and technological progress’, in P. Dasgupta and P. Stoneman (eds) Economic Policy and Technological Performance, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Stinchcombe, A. L. (1990) Information and Organizations, Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Stoneman, P and Diederen, P. (1994) ‘Technology diffusion and public policy’, Economic Journal 104: 918–30.

Thompson, G. V. (1954) ‘Intercompany technical standardization in the early American automobile industry’, Journal of Economic History 14(1): 1–20.

Thompson, J. D. (1967) Organizations in Action: Social Sciences Bases of Administrative Theory, New York: McGraw-Hill.

Tushman, M. L. and Anderson, P. (1986) ‘Technological discontinuities and organizational environments’, Administrative Science Quarterly 31: 439–65.

Utterback, J. M. (1994) Mastering the Dynamics of Innovation: How Companies Can Seize Opportunities in the Face of Technological Change, Boston, Mass.: Harvard Business School Press.

Weder, R. and Grubel, H. G. (1993) ‘The new growth theory and Coasean economics: institutions to capture externalities’, Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv 129(3): 488–513.