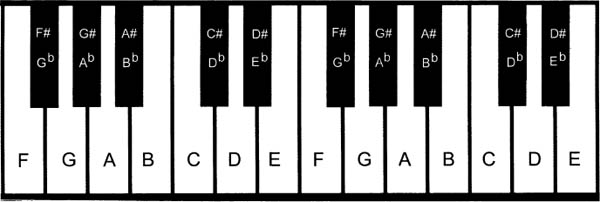

Melody refers to the succession of individual pitches used to express musical contour and shape. These pitches have letter names, A to G, and appear on the keyboard below (figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1. Keyboard with pitch names

The distance between any two adjacent keys is a semitone (ST), commonly referred to as a half step. For example, E to F and F to F# is a semitone (figure 1.2). Two adjacent semitones create a whole tone (WT), also known as a whole step. For example, G to A is a whole tone (figure 1.3).

Figure 1.2. Semitones

Figure 1.3. Whole tones

Alterations to named pitches are called accidentals. A sharp (#) raises a pitch by a semitone. Conversely, a flat  lowers a pitch by a semitone. A double sharp

lowers a pitch by a semitone. A double sharp  raises a pitch by two semitones, while a double flat

raises a pitch by two semitones, while a double flat  lowers a pitch by two semitones. A natural

lowers a pitch by two semitones. A natural  ) cancels a previous alteration. An accidental affects the note that follows as well as all notes of the same pitch within a measure.

) cancels a previous alteration. An accidental affects the note that follows as well as all notes of the same pitch within a measure.

A stepwise sequence of semitones or whole tones creates a pattern; whether in ascending or descending order, these patterns create scales. A scale that is built entirely of semitones is a chromatic scale (figure 1.4).

Figure 1.4. Staff with chromatic scale

Measure 55 of “Chop Suey,” from Flower Drum Song features a chromatic scale in the top note of the accompaniment (figure 1.5).

Figure 1.5. “Chop Suey,” mm. 52–56, chromatic scale

A seven-note scale built on a combination of semitones and whole tones is a diatonic scale (figure 1.6).

Figure 1.6. Staff with diatonic scale

An example of a melody made up of diatonic scale tones appears in measures 1-6 of “You Are Love” from Show Boat. (Notice that the melody is doubled and reinforced in the accompaniment; see figure 1.7).

Figure 1.7. “You are Love,” mm. 1-6, diatonic scale

Mode refers to the resulting color or tonality elicited from scales or melodic sequences. The two most common modes in Western music are the major and minor modes. They consist of eight notes. For purposes of this book, these two modes will be emphasized.

Typically, the major mode is perceived to be “positive,” “bright,” or “effusive,” while the minor mode is perceived to be “negative,” “dark,” or “reflective.” Reference to the major mode is notated by capital letters. Lowercase letters are used to reference minor modes. Therefore, an uppercase A represents A-major, and the key of a-minor is represented by a.

Figure l.8a. C-major scale

An ascending major scale has the following formula (this pattern is reversed for the descending scale): Starting Note/WT/WT/ST/WT/WT/WT/ST (see figures 1.8a and 1.8b).

Figure 1.8b. B-flat major scale

Stephen Sondheim outlines an ascending E-major scale in measures 30 and 31 of “The Little Things You Do Together,” from Company. The melody begins on the second scale degree, the F#, and ascends to the high E (see figure 1.9).

Figure 1.9. “The Little Things You Do Together,” mm. 29–31, ascending E-major scale

There are three common forms of minor modes: natural, harmonic, and melodic. The natural minor scale has the following formula: Starting Note/WT/ST/WT/WT/ST/WT/WT (see figure 1.10).

Figure 1.10. e-natural minor scale

The harmonic minor mode raises the seventh scale degree of the natural minor scale. It utilizes the following formula: Starting Note/WT/ST/WT/WT/ST/WT+ST/ST. Notice that the distance of the second-to-last interval in this formula is three semitones (a step and a half). Most Western melodies that are written in a minor mode are in the harmonic form (figure 1.11).

Figure 1.11. e-harmonic minor scale

The melodic minor mode raises the sixth and seventh scale degrees ascending by one semitone and then follows the natural minor formula descending. The ascending melodic minor scale follows the formula: Starting Note/WT/ST/WT/WT/WT/WT/ST (see figures 1.12a and 1.12b). Therefore, the descending melodic minor scale is the same as the descending natural minor scale.

Figure 1.12a. e-melodic minor scale (ascending)

Figure 1.12b. e-melodic minor scale (descending)

In any key, scale degree notes have specific names. The first scale degree is the tonic, the second is the supertonic, the third is the mediant, the fourth is the subdominant, the fifth is the dominant, and the sixth is the submediant.

In a discussion of scales and modality, special notice should be taken of the mediant. This third scale degree is important because it establishes either major or minor mode.

The seventh degree of major and the various minor scales is “variable.” In some cases, the distance below tonic is a semitone, while in others it is a whole tone. In the major mode, the seventh scale degree is the leading tone because it is a mere semitone from the tonic, which gives it a feeling of leading to or resolving to the tonic. The same is true with the harmonic minor and the ascending melodic scales. In the natural and the descending melodic scales, the seventh scale degree is the subtonic because this now-lowered tone is a whole tone below the tonic. Finally, the eighth scale degree is the octave or high tonic (figures 1.13a and 1.13b).

Figure 1.13a. Major scale with scale degree names

Figure 1.13b. Natural minor scale with scale degree names

When any two pitches sound consecutively or simultaneously, the distance between each is an interval. Intervals are defined by two components—size and quality. They can be perceived aurally as well as visually. In order to determine interval size visually, start with the bottom note and count lines and spaces to the upper note. Be sure to count both the starting and ending notes. For example, on the staff below, starting on C and ending on the same C is a unison. Starting on C and ending on D, the interval is a second. The distance from C to E is a third, and so forth. An interval of an eighth is an octave (figures 1.14 and 1.15).

Figure 1.14. C-major intervallic scale

Figure 1.15. c-minor (natural) intervallic scale

Notice on the major and minor scales above that the thirds, sixths, and sevenths would sound different, depending upon the mode. In addition, the specific distance (number of semitones or whole tones) has changed. These variances represent the interval quality. We define these intervallic qualities as major, minor, perfect, diminished, and augmented. Perfect intervals are intervals that are the same in major and minor modes. These intervals are typically described as “open” and “hollow.”

The interval size and qualities from the tonic are labeled on the C-major scale above (figure 1.14). Notice that the unison, fourth, fifth, and octave are perfect (P), and the second, third, sixth, and seventh intervals are major (M).

The interval size and qualities (again from the tonic) are labeled on the c-natural minor scale above (figure 1.15). As is the case in a major mode, the unison, fourth, fifth, and octave remain perfect. Likewise, the second remains major. However, the third, sixth, and seventh intervals are now minor (m). Considering the intervals of the third, sixth, and seventh in both scales, the major interval is “bigger,” while the minor interval is “smaller.”

The word “augment” means to increase, and “diminish” means to decrease. When a perfect fourth is augmented or a perfect fifth is diminished they create a tritone. A tritone is three whole tones (figure 1.16).

Figure 1.16. Augmented fourth or diminished fifth

An augmented fourth and a diminished fifth sound the same. Enharmonic equivalents are pitches that sound the same but are written differently. For example, a D-sharp and an E-flat are the same pitch, but with different spellings. The same is true of F and E-sharp. Actually, each tone can be written in one of two or three ways (figure 1.17).

Figure 1.17. Enharmonic equivalents

In the context of a major or minor scale, the tritone does not appear as an interval above or below the tonic, but it can be embedded within the scale. For example, in a major scale, the distance between the subdominant and the leading tone is an augmented fourth (figure 1.18).

Figure 1.18. Augmented fourth in a major scale

For each scale, key is the means of identifying the tonal center (root or tonic) and mode. Sharps and flats indicate the key signature at the beginning of a composition. Key signature can change at any point as modulations (or shifts in tonal center) between keys occur. As already stated, key signatures may contain accidentals.

The order of sharps in a key signature is always the same (figure 1.19).

Figure 1.19. Order of sharps

The order of flats in a key signature is always the same (figure 1.20).

Figure 1.20. Order of flats

The number of accidentals in a key signature identifies the key’s tonic. For example, one sharp (F#) is the key signature for G-major. So, if one begins a scale on G and then follows the formula for a major scale, one finds that the leading tone is F-sharp. The major key signatures follow (figure 1.21).

Figure 1.21. Major key signatures

The circle of fifths is another system of key identification. It considers the increasing number of sharps or flats in the signatures. Starting with C-major (no sharps or flats) and moving clockwise by ascending fifths, one reaches G-major (one sharp). Ascending a fifth again, one reaches D-major (two sharps), and so on. After twelve steps, one returns to C-major. Likewise, starting with C-major (no sharps or flats) and moving counterclockwise by descending fifths, one reaches F-major (one flat). Descending a fifth again, one reaches B-flat major (two flats), and so on. After twelve steps, one returns again to C-major (figure 1.22).

Figure 1.22. Circle of fifths

The astute student will memorize key signatures. As an aid in retention, the following tips may prove helpful.

To determine a major key in a key signature containing sharps, simply name the sharp farthest to the right in the key signature and go up one letter name. Then add the word “major” and that is the key. For example, in the key of E-major, the sharp in the key signature that is the farthest right is D. Therefore, if one goes up one letter name, one arrives at E, hence E-major.

To determine a major key in the key signature containing flats, simply name the flat second from the right in the key signature and add the word “flat” to its letter name. Then add the word “major” and that is the key. For example, the key signature of  -major shows an

-major shows an  as the second from the right.

as the second from the right.

The exception to the system above is that if there is only one flat in the key signature, the key is F-major. If there are no flats or sharps in the key signature, the key is C-major.

Key signatures apply to minor scales as well. Each major key has a relative natural minor which is down, intervalically, a minor third. That is, C-major’s relative minor key is A-minor. Therefore, the key of A-natural minor has the same key signature as C-major; it simply begins on A rather than on C. Using that key signature, one merely adds the appropriate accidentals to construct the harmonic and melodic variations of the minor mode (figure 1.23).

Figure 1.23. C-major scale and its relative minor

In “King Herod’s Song” from Jesus Christ Superstar, Andrew Lloyd Webber begins the song in f-sharp minor. At measure 9, the relative key, A-major, is established and evident in the shift from a darker, ominous quality to one that is brighter (figure 1.24).

Figure 1.24. “King Herod’s Song,” mm. 1–4 and 9–16, relative key relationship

Note that in measures 15 and 16, A-major is reinforced with the descending major scale in the melody.

One other key relationship is the parallel. Parallel key relationships have the same tonic but different key signatures and notes. For example, d-minor is the parallel minor of D-major.

Notice on the scales below, C-major has no sharps or flats in the key signature (figure 1.25a). A c-minor scale has three flats (figure 1.25b), reflected in the key signature (figure 1.25c). If those three flats are translated into the key signature for the appropriate major key, it would be E-flat major (figure 1.25d). Note that E-flat major’s relative minor, then, is c-minor (an interval of a third below).

Figure 1.25a. C-major scale

Figure 1.25b. c-natural minor scale

Figure 1.25c. c-natural minor scale with key signature

Figure 1.25d. E-flat major scale with key signature

Composers can use the device of mutation, or changing mode to a parallel major or minor, without altering the key. The song “Far from the Home I Love” from Fiddler on the Roof provides a clear example. The song begins in the key of c-minor. At measure 12, through the use of accidentals and an ascending C-major scale in the accompaniment, the parallel major key is established to reinforce the happy recollection (figure 1.26).

Another example of mutation appears in “I Enjoy Being a Girl,” from Flower Drum Song. In this instance, the key shift is from D-major to d-minor (figure 1.27).

The musical theatre examples quoted thus far are evidence of the potency of melody as a guide to the listener and to the performer. When one considers harmony as an extension of the melodic expression, an infinite number of musical possibilities unfold. Harmony can reinforce emotion and dramatic action, and sustain a mood.

Figure 1.26. “Far from the Home I Love,” mm. 5–16, mutation

Figure 1.27. “I Enjoy Being a Girl,” mm. 53–63, mutation

Harmony refers to the simultaneous sounding of two or more pitches or tones. This coupling of tones begins to characterize sound just as a coupling of people begins to characterize a conversation or relationship. Primarily, harmony references music vertically, while melody suggests a linear or horizontal orientation.

Harmony is organized in many ways, but the underlying principle behind harmony is tertian—chords built in thirds. A triad is a three-note chord that contains a root or starting note, the note a third above the root, and a note a fifth above the root. Four examples of triads built on C appear below (figures 1.28a, 1.28b, 1.28c, and 1.28d).

Figure 1.28a, Figure 1.28b, Figure 1.28c, Figure 1.28d. Four triads built on C

The third and the fifth notes of the triad indicate mode. When the distance between the root and fifth of a triad is perfect, the modality is either major or minor. In the example above, figures 1.28a and 1.28b are major and minor triads. The determining factor in this case is the interval between the root and the third above. When the distance between the root and the fifth is reduced by one semitone, it is a diminished triad. In this case, there will always be an interval of a minor third between the root of the chord and the third (figure 1.28c). Conversely, when the interval of the fifth is raised by one semitone, it is an augmented triad and will always contain a major third between the root and third (figure 1.28d).

Just as the mode of intervals is indicated by upper- or lowercase letters, the mode of triads is indicated by upper- or lowercase Roman numerals.

The triadic scale in a major key features major triads on the tonic, fourth, and fifth scale degrees. They are identified by the Roman numerals I, IV, and V. The triadic scale in a minor key features minor triads on the second, third, and sixth scale degrees. They are identified by the lowercase Roman numerals ii, iii, and vi. A diminished triad (lowered by one semitone) is found on the seventh scale degree in a major scale. It is thus identified by a lowercase Roman number vii followed by a °, as in vii° (figure 1.29).

Figure 1.29. C-major triadic scale

The triadic scale above is in the key of C-major, evidenced by the fact that there are no accidentals in the key signature and it begins and ends on c. The triadic scale for a-minor (the relative minor of C-major) follows (figure 1.30).

Notice that the a-natural minor triadic scale features major chords constructed on the third, sixth, and seventh scale degrees. They are identified by the Roman numerals III, VI, and VII. Chords constructed on the tonic, fourth, and fifth scale degrees are minor and are identified by the lower-case Roman numerals i, iv, and v. The triad built on the second scale degree is diminished and is identified by a lowercase Roman number ii followed by a °, as in ii°. Notice that the augmented triad is not present in the major or the natural minor scale. It does appear, however, on iii in both harmonic and ascending melodic minor scales. It is a unique and versatile compositional device that adds expressive variety to music. Because it is a triad constructed of stacked major thirds, the notation is an uppercase Roman numeral followed by a +, as in III+ (figure 1.31).

Figure 1.30. a-minor (natural) triadic scale

Figure 1.31. a-harmonic minor

The introduction to “Chop Suey” is in the key of C-major and the treble clef features a sequence of parallel triads that include major, minor, and diminished sonorities (figure 1.32).

Figure 1.32. “Chop Suey,” mm. 1–4, parallel triads

Thus far, we have considered triads in root position only—that is, stacked thirds with the root on the bottom. There are two alternative voicings for triads that, by virtue of the rearranged tones, can alter the feeling of tonal stability. By taking the root of the triad and placing it an octave above, the third of the triad is now the bottom note. As such, the notes are no longer arranged by stacked thirds. The upper notes are now a sixth and a third above the bottom note. This is notated with a subscript6 next to the Roman numeral and is in first inversion. Because triads are inherently built on a system of thirds, it is not necessary to notate the third that exists between the bottom two notes (figure 1.33).

Figure 1.33. Root and first inversion triads

Triads in second inversion feature the third of the triad now an octave higher, leaving the fifth of the triad as the bottom note. The resulting intervals above that fifth are now a sixth and a fourth. In this case, the subscript  is notated (figure 1.34).

is notated (figure 1.34).

Figure 1.34. Root position, first and second inversion triads

A shift between root-position and second-inversion triads is captured in “Love, Look Away,” from Flower Drum Song. Notice that, in measures 5–7, the melody outlines two consecutive minor triads—g-minor and f-minor, and then a diminished triad in measure 9. In the accompaniment of measure 6, Richard Rodgers has spelled a sequence of parallel triads in first inversion (in this case, major, minor, major, minor; see figure 1.35).

Figure 1.35. “Love, Look Away,” mm. 5–9, parallel triads

Inversions of triads do not change the mode, so upper- and lowercase notation remains consistent. What changes, however, is the perceived stability and coloring of the chord. Depending upon the context, a first-in-version triad may sound less “final” than a root-position triad. Similarly, in a second-inversion chord, burying the root within the chord obscures the feeling of stability or finality. Additionally, with the exposed third on the top, the mode is much more apparent, and it suggests harmonic or melodic movement.

In the introduction to this book, a parallel was drawn between a playwright’s use of literal language and a composer’s use of musical language. If chords form “words,” then musical phrases form “sentences” that must be punctuated.

A cadence is a progression of two or more chords at the end of a musical phrase. In a way, a cadence functions as a “period,” an “exclamation point,” or a “comma.” The cadence V to I is an authentic cadence. Because the authentic cadence features the dominant and tonic scale degrees, it represents the strongest (and most common) musical punctuation. The cadence IV to I is a plagal cadence and is the second-most-common cadential pattern in Western music. A deceptive cadence is one in which the progression from the dominant chord denies resolution to the tonic, and replaces it with resolution to iii or to vi. A half cadence is one in which the final chord is a V (figures 1.36a, 1.36b, 1.36c, and 1.36d).

Figure 1.36a, Figure 1.36b, Figure 1.36c, Figure 1.36d. Cadences

Harmony is not limited to triadic structures. Stated simply, it is possible to stack additional thirds above the triad. The most common use of this extended tertian harmony is the addition of the seventh. Added ninths, elevenths, and thirteenths are higher-order tertian (H.O.T.) chords and, like seventh chords, provide richer harmonic color and character.

Remember that the relationship between the root and third of a triad determines major or minor modality. The relationship of root to fifth characterizes perfect, augmented, and diminished qualities. Because of the additional third, seventh chords have a two-name moniker. The first name refers to the root-third (major or minor) relationship. The second name refers to the root-seventh relationship. Therefore, many seventh chords are either Major-Major (MM), Major-minor (Mm), minor-minor (mm), or minor-Major (mM). Additionally, in the case of a root-fifth relationship that is diminished, a seventh chord with a minor seventh is called half diminished and a seventh chord with a diminished fifth and a diminished seventh is called (fully) diminished (figure 1.37).

Figure 1.37. Seventh chords

Stephen Sondheim exploits a variety of higher-order tertian chords in the accompaniment to “Side by Side by Side,” from Company, possibly in order to express a disconnect between what is being sung and what Bobby, the main character, is feeling. In measure 29, there is a half-diminished seventh chord. Minor-Major seventh chords appear in measures 31 and 37. Measures 63 and 64 feature a Major-minor ninth followed by a minor-minor ninth chord (figure 1.38).

Figure 1.38. “Side by Side by Side,” mm. 29–32, 37–40, 63–64, examples of seventh and ninth chords

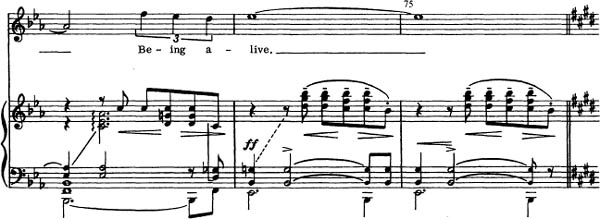

It is important to note that vertical construction of triads and chords is not the only manner in which higher-order tertian harmony can be utilized. Sometimes, it is the accumulation of chord tones shared between melody and accompaniment and developed over the course of a number of beats that “implies” the ninth, eleventh, and thirteenth harmony. A classic example is in Sondheim’s “Being Alive,” from Company. For instance, in the example below, notice that the accompaniment of the whole of measure 20 spells an (incomplete) thirteenth chord—e-flat, g, b-flat, (d), f, a-flat, c. Later in the same song, as the drama builds to a climax, this higher-order sensibility is intensified as Sondheim now thickens the texture of the accompaniment and places the thirteenth of the chord in the melody—b, (d-sharp), (f-sharp), a, c-sharp, e, g-sharp (figure 1.39).

Figure 1.39. “Being Alive,” mm. 20–21, 131–136

Exposition, rise in conflict, climax, and resolution tie musical composition to principles of storytelling. Harmony can exist on two levels: vertical and horizontal. Much of the discussion above addresses harmony in a stacked or vertical context. In this way, harmony is creating the “words” of music. Perhaps harmony’s greatest function, however, is its ability to provide forward movement, thereby establishing the “thought” or “sentence” of music. The combination of harmony and melody, traveling forward in time, creates a complete statement that is a harmonic progression. Harmonic progressions often operate on a basic level within the key—for example, a tonic moving toward a dominant and eventually returning to tonic.

Functional harmony is the prevailing harmonic language of Western music and as such is the predominant harmonic idiom of American popular music. Since the music of the American musical theatre began firmly rooted as the popular music of the country, it logically adopted this functional harmonic vocabulary in a majority of its repertoire. Whether chords associate with melody or interact with other chords, functional harmony results in an emotional impulse that has proven nearly universal. These impulses serve as powerful cues for performers and listeners alike. Functional harmony establishes an emotional current that directs music to an emotional destination. These “progressions” of chords create syntax.

A tonic chord, for example, can move to any other chord in a key, and that initial movement may suggest subsequent progressions (figure 1.40).

Figure 1.40. Tonic chord progressions

In general terms, a dominant chord moves with ease to a tonic or to a submediant (in which case the aforementioned deceptive cadence results). A dominant can also move with ease to a subdominant chord (figure 1.41).

Figure 1.41. Dominant chord progressions

A subdominant chord typically progresses to a dominant, submediant, supertonic, or tonic chord (in the latter case, a plagal cadence results; see figure 1.42).

Figure 1.42. Subdominant chord progressions

A supertonic chord generally moves to a dominant or to a tonic chord (figure 1.43).

Figure 1.43. Supertonic chord progressions

A submediant leads to the subdominant or to the supertonic chord (figure 1.44).

Figure 1.44. Submediant chord progressions

The same rules that govern two-chord progressions can be applied to multichord progressions (figure 1.45).

Figure 1.45. Multichord harmonic progressions

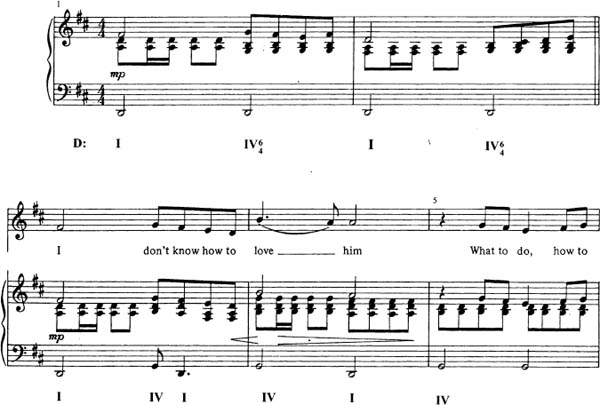

In the excerpt below, composer Andrew Lloyd Webber uses a traditional chord progression to accompany the melody of “I Don’t Know How to Love Him.” Webber’s chords progress from tonic to some other sonority and then back again. Furthermore, those additional sonorities are closely related (figure 1.46).

Figure 1.46. “I Don’t Know How to Love Him,” mm. 1–8, traditional chord progression

A basic four-measure chord progression appears below. Note that the melody constructed above it consists of tones that are derived from the supporting accompaniment. That is, the melodic tones above the tonic chord (I) are C, E, or G. When the harmony changes to the subdominant (IV), the melody consists of F, A, or C, etc. (figure 1.47).

Figure 1.47. Simple chord-tone melody with accompaniment

The song “Can’t Help Lovin’ Dat Man,” from the classic musical Show Boat, provides a clear illustration of another traditional chord progression supported by a chord-tone melody (figure 1.48).

Figure 1.48. “Can’t Help Lovin’ Dat Man,” mm. 1–4, traditional harmony with chord-tone melody

Music’s richness lies in the combination of melody and harmony. It is possible to enhance melodic and harmonic vocabulary with the addition of nonharmonic tones. A nonharmonic tone is foreign to the momentary harmony, and its tonal function is to expand the musical context. The example below is identical to the example above except for the addition of nonharmonic tones that provide variety and interest (figure 1.49).

Figure 1.49. Simple melody with nonharmonic tones and accompaniment

Nonharmonic tones fall into two basic categories—rhythmically weak and rhythmically strong—and each one is identified easily by certain characteristics. A passing tone occurs between two stepwise notes on an unaccented beat and can move in any direction. It can be either diatonic (figure 1.50a) or chromatic (figure 1.50b).

Figure 1.50a. Diatonic passing tone

Figure 1.50b. Chromatic passing tone

Jason Robert Brown’s “Christmas Lullaby” from Songs for a New World and Jerry Bock and Sheldon Harnick’s “Matchmaker, Matchmaker” from Fiddler on the Roof illustrate two different treatments of the use of passing tones (figures 1.51a and 1.51b). In the case of “Christmas Lullaby,” accented passing tones serve as an ornament on a monosyllabic word. In “Matchmaker, Matchmaker,” the unaccented passing tones are used melodically.

Figure 1.51a. “Christmas Lullaby,” mm. 28–31, diatonic passing tone

Figure 1.51b. “Matchmaker, Matchmaker,” mm. 35–42, diatonic passing tones

An anticipation is a tone that foreshadows an approaching harmonic change. In the example below, note that the nonharmonic tone becomes harmonic upon resolution (figure 1.52).

Figure 1.52. Anticipation

In “Christmas Lullaby,” the anticipation is not used cadentially but as part of the harmonic progression (figure 1.53).

Figure 1.53. “Christmas Lullaby,” mm. 78–85, anticipations

Conversely, a retardation forestalls, by melodic extension, a complete harmonic resolution. In the example below, note that the nonharmonic tone delays the full resolution to the V chord (figure 1.54).

Figure 1.54. Retardation

An échappée is a nonharmonic tone that “escapes” resolution in the “wrong” direction by step and then resolves by a leap of a third in the “right” direction (figure 1.55).

Figure 1.55. Échappée

Jerome Kern used an échappée to great effect in “You Are Love,” from Show Boat. By ascending to the G, Kern seems to underscore the importance of the verb in the lyric (figure 1.56).

Figure 1.56. “You Are Love,” mm, 57–59, échappée

A cambiata is a nonharmonic tone that overshoots in the direction of resolution by a third and resolves by step in the opposite direction as the harmony is maintained (figure 1.57).

Figure 1.57. Cambiata

A cambiata appears in measure 18 in Stephen Sondheim’s song “Sorry-Grateful,” from Company (figure 1.58).

Figure 1.58. “Sorry-Grateful,” mm. 17–18, cambiata

Neighbor tones are melodic ornaments that move stepwise (diatonically or chromatically) away from and back to a given harmonic tone (figure 1.59).

Figure 1.59. Neighbor tones

Two examples of neighbor tones appear below. The first, a lower-neighbor tone, is in “I Enjoy Being a Girl,” from Rodgers and Hammer-stein’s Flower Drum Song (figure 1.60a.) An upper-neighbor tone appears in Jason Robert Brown’s “I’m Not Afraid,” from Songs for a New World (figure 1.60b).

Figure 1.60a. “I Enjoy Being a Girl,” mm. 28–31, lower-neighbor tone

Figure 1.60b. “I’m Not Afraid,” mm. 13–14, upper-neighbor tone

There are two rhythmically strong nonharmonic tones: the appoggiatura and the suspension. The appoggiatura sounds on a strong beat and then resolves afterwards. The examples below show various appoggiatura configurations of a D-major triad (figure 1.61).

Figure 1.61. Appoggiaturas

Turning to “Can’t Help Lovin’ Dat Man” again, Kern uses the appoggiatura on beat 3 in measure 20 (figure 1.62).

The example below features a “prepared appoggiatura” with the nonharmonic tone sounding in the preceding chord (figure 1.63).

Figure 1.62. “Can’t Help Lovin’Dat Man,” mm. 19–22, appoggiatura

Figure 1.63. Prepared appoggiatura

A prepared appoggiatura appears in measures 3–9 of “Matchmaker, Matchmaker” (figure 1.64).

Figure 1.64. “Matchmaker, Matchmaker,” mm. 3–9, prepared appoggiatura

A suspension is the same as a prepared appoggiatura with the exception that the dissonant note is repeated or tied from the chord preceding (figure 1.65).

Figure 1.65. Suspension

A suspension in measure 8 in the inner voice of the accompaniment of “Love, Look Away” adds harmonic interest (figure 1.66).

Figure 1.66. “Love, Look Away,” mm. 5–8, suspension

Nonharmonic expression is not limited to melody. Harmony can be extended by the use of nonharmonic tones, thereby revealing an array of musical possibilities. Just as higher-order tertian structures provide the opportunity for musical interest and variety, so music can “travel” away from its tonal center through a reconceptualization of the dominant chord. Every scale degree has a fifth above and below it. Building a triad on the fifth of any scale degree adds a layer of harmonic context. This emphasis of the dominant scale degree echoes the notion of the circle of fifths as a way of considering harmonic relationship.

In the example below, note the tonic triad in C-major. Next to it is a major triad built on the dominant scale degree (G–B–D). What follows is a major triad built on the D, the fifth of the dominant triad. The major triad built upon this D is D–F#–A. The presence of the F# clearly moves away from C-major. It cannot be analyzed as a ii chord in C-major, for that would have to be a minor triad. This major chord functions as the dominant of the dominant, or V of V in C-major (figure 1.67).

Figure 1.67. Example of the V/V chord in C-major

Likewise, this concept can be applied to any scale degree within the key. One could build the triad on the second degree, note its fifth, the A, and build a major triad on that A, resulting in a chord spelled as A–C#–E. This is the V of ii in the key of C-major. This approach to harmony allows a composer to move away from a tonal center without a formal modulation. It allows for more complex musical expression and can facilitate formal modulation. Modulation takes place when a new dominant-tonic relationship is firmly established.

Another compositional device that adds more harmonic tension than a plain dominant triad, particularly when a change in key in imminent, is the dominant seventh chord. It functions as the dominant triad does, but with a more urgent tendency to progress to the tonic (figure 1.68).

Figure 1.68. Example of V7 chord in the key of C-major

Just as harmonic progression provides forward movement of musical thought, modulation from one key to another can add an additional layer of intensity, urgency, and interest to the musical journey. The heightened emotion inherent in theatre music occurs as the character moves through conflict toward resolution. Modulation can be the composer’s nonverbal contribution to that journey. It can occur in several ways. The transition from an established key to a destination key can be smooth or abrupt. Modulation relies upon cadential patterns or a new key signature to be complete.

Two keys may share common chords. For example, a V in C-major is also a I in G-major. When one chord is a bridge from an established key to a destination key, a common chord modulation has occurred. The common chord acts as a “pivot,” facilitating the movement between the keys.

“A New World” from Jason Robert Brown’s Songs for a New World provides an interesting example of a strong modulation from E-flat major to B-flat major. Note that the E-flat major chord in measure 68 (the tonic or I) is also a IV in the destination key of B-flat major. The addition of an F pedal point in the bass (dominant reinforcement of the new key) strengthens the modulation. A pedal point is a tone that is sustained in the bass as harmony above changes (figure 1.69).

Figure 1.69. “A New World,” mm. 58–72, common-chord modulation

A second type of modulation, enharmonic modulation, occurs when one chord in the established key is spelled enharmonically in the destination key. In measure 60 from Stephen Sondheim’s “Losing My Mind” from Follies, the chord is spelled G-flat, B-flat, D-flat, E-natural (a subtonic harmony in the original key) on beat 1. Its repetition on the third beat is spelled f-sharp, a-sharp, c-sharp, e—the dominant-seventh chord of B-major, the destination key (figure 1.70).

Figure 1.70. “Losing My Mind,” mm. 59–61, enharmonic modulation

From the earliest days of American musical theatre, excitement has been generated by one of the most frequently encountered shifts in tonal center that exists: sudden upward modulation by half step without the utilization of a common chord. Used to great effect in musical theatre literature, it is the direct or abrupt modulation. This type of modulation features a cadence in the established key that is followed by the next phrase in a new key, often a semitone or whole tone higher. This modulation has the effect of “shifting without a clutch,” because the musical energy parallels a sudden or urgent rise in emotional intensity.

A classic example of the power of an abrupt modulation can be found in Stephen Sondheim’s “Being Alive” from Company. To build intensity toward a musical and dramatic climax, the song ascends abruptly from E-flat major to E-major with no preparation (figure 1.71).

Figure 1.71. “Being Alive,” mm. 73–77, abrupt modulation

Sometimes, a piece of music can start and end in a particular key but will temporarily modulate to a new key without formally altering the key signature. The chorus of “Ol’ Man River,” from Show Boat, by Jerome Kern, is a classic example. In the excerpt below, the chorus begins and ends in the key of C-major. The addition of accidentals (F-sharp and D-sharp) moves the key of the bridge to e-minor without altering the key signature. The new key is established at the outset of the bridge, but the vacillation between I and V (e-minor, B-major) is in the accompaniment. This tonic-dominant relationship is reiterated further by the prominence of an A-natural in the melody, implying a dominant seventh context. The return to the original key is facilitated in measures 32 and 33. The e-minor chord serves as both i in the bridge and also iii in C-major, the return of the original key (figure 1.72).

Figure 1.72. “Ol’Man River,” mm. 15–34, temporary modulation

A musical statement is not complete without a sense of movement. Rhythm achieves forward motion in music. Whether simple or complex, rhythm provides information that further defines character and dramatic situation.

Rhythm refers to the pattern established by unit duration. Meter is the regular recurrence of alternating stressed and unstressed beats or units. As such, notes that are combined to create rhythmic patterns vary in duration. Likewise, rests, or durations of silence, have varying values (figure 1.73).

Figure 1.73. Note and rest symbols

Dotting a note or rest adds half of its value to it.

Measures divide meter into regularly recurring divisions. Vertical lines on the staff, bar lines, indicate measures (also called bars).

A time signature typically appears at the beginning of every composition. It indicates the initiation of a new meter once the initial time signature has been established. The upper number in a time signature indicates the number of beats per measure. The lower number in a time signature indicates the type of note that receives one beat (figure 1.74).

Figure 1.74. Staff with time signatures, bar lines, and rhythmic patterns

An exception to the rest notation explained above is that a whole rest also indicates an entire measure of silence regardless of the time signature. For instance, in  time, an entire measure of rest would be notated with a whole rest rather than with a dotted half rest. Similarly, in

time, an entire measure of rest would be notated with a whole rest rather than with a dotted half rest. Similarly, in  time, a whole rest indicates an entire measure of silence rather than a dotted half rest (figure 1.75).

time, a whole rest indicates an entire measure of silence rather than a dotted half rest (figure 1.75).

Figure 1.75. Whole rest in various metrical settings

The time signature  is known also as “common time” as shown below (figure 1.76).

is known also as “common time” as shown below (figure 1.76).

Figure 1.76. Symbol for common time or

In cut time  , the half note, rather than the quarter note, receives the beat. The symbol for cut time is shown below (figure 1.77).

, the half note, rather than the quarter note, receives the beat. The symbol for cut time is shown below (figure 1.77).

Figure 1.77. Symbol for cut time

Rhythmic patterns having two beats or multiples thereof  are in duple meter. Likewise, rhythmic patterns having three beats

are in duple meter. Likewise, rhythmic patterns having three beats  are in triple meter. In

are in triple meter. In  and

and  time, the first beat (downbeat) is accented, while the last beat (upbeat) is unaccented. In

time, the first beat (downbeat) is accented, while the last beat (upbeat) is unaccented. In  and

and  time, the first beat is accented, while the second and third beats are unaccented. In

time, the first beat is accented, while the second and third beats are unaccented. In  time, there are two accents felt—the first and third beats.

time, there are two accents felt—the first and third beats.

Tempo, or relative speed of rhythm, can affect the way meter is perceived. For example, a quick  or

or  meter may be perceived in one predominant pulse per measure. Likewise,

meter may be perceived in one predominant pulse per measure. Likewise,  may be perceived as having two predominant accents, on beats 1 and 4, while

may be perceived as having two predominant accents, on beats 1 and 4, while  can be subdivided into three, with predominant accents on beats 1, 4, and 7, thereby classifying it as a form of triple meter. And

can be subdivided into three, with predominant accents on beats 1, 4, and 7, thereby classifying it as a form of triple meter. And  can be subdivided into four.

can be subdivided into four.

The form of musical theatre literature can be as varied as any other musical genre. But, because the roots of musical theatre literature are found in popular music, whose forms are necessarily short, there are general structural components common to most of the repertoire from the late nineteenth century onward.

Most musical theatre songs begin with an instrumental introduction. The introduction can be of varying length. It can be as simple as a single note that provides a starting pitch for the singer or as complex as a multimeasure cell that introduces a musical motif.

The introduction typically is followed by the verse. The text of the verse tends to be expository, that is, it provides key background information, and, therefore, the music serves as transition from speech into singing. As such, it is performed generally in a more rhythmically free manner that reflects speechlike patterns.

It is usually the chorus that is the most memorable section of a musical theatre song. The text brings specificity to the notions expressed in the verse. Because the focus of the lyric is narrow, the musical structure is more concise. A typical chorus is built of four eight-measure phrases. For the purpose of analysis, each phrase is identified by a letter. Sections that are closely related are assigned the same letter, while contrasting sections receive other letters. The most frequently found form is AABA, in which the A sections are exact or near-repeats of each other. The B, also called the bridge or release, features contrasting music, often in a relative or parallel key. The text of the bridge provides reflection and prepares the climactic return of the final A section. Other common song forms include ABA, ABAB, and ABACA (rondo form).

The end of a song can be extended by either a coda, a short variation serving as a finishing theme, or a rideout, which is an instrumental “tag” that punctuates the song.

These patterns, all of which feature some form of musical repetition, are known as strophic structures.

Many musical theatre songs written in these compact forms feature additional or new lyrics and repeat the chorus. The repetition that characterizes the strophic form has served an important role in the development and popularity of the musical theatre song. Nowadays, it is not uncommon for audience members to be familiar with the songs prior to seeing the live production of a new musical. But in years past, before records, tapes, CDs, and iPods, composers and publishers relied upon word of mouth as a primary means to market their product. Therefore, if the musical material was repeated enough in one song and the song reprised numerous times throughout the evening, audience members would leave the theatre humming the tunes. This increased the likelihood that they would purchase the sheet music. Tin Pan Alley blossomed and thrived on this marketing strategy since, at that time, the piano was a prominent part of the American culture. The piano parlor was the social center of neighborhood life. Neighbors and friends would gather around the piano to sing the newest Broadway hit, thereby ensuring a wider audience for the songs. In those days before radio, television, and the recording industry, this was the way music was popularized and, unlike today, the popular music of the day was the music of the stage. Compact musical forms are less necessary in the modern musical theatre. Through-composed songs, extended songs written with no sectional repetition, are becoming more and more prevalent as a result of today’s audiences’ ability to digest more complex compositions.

This fundamental exploration of the mechanics of music theory is little more than the “what” and “where.” The “how” is the real point of this text—How can an artist use what he or she knows of melody, harmony, and rhythm and parlay that into an informed and vital performance? The next part of this book is a series of essays created by the authors that can serve as a model demonstrating how to use the principles of music theory as a means of gaining deeper insight into musical dramatists’ original intent.