“A good farmer is nothing more nor less than a handyman with a sense of humus.”

— E. B. White

Healthy plants are like healthy people. They have strong natural mechanisms at work to ward off potential trouble. They self-correct. Gardeners can support these systems in numerous ways: by paying attention, by deferring to climate when making plant choices and choosing varieties, and by meeting a plant’s fundamental requirements for placement and care.

Plant diversity is one feature of a healthy garden. An elaborate dance is at work here, with a beauty, order, and intelligence of its own.

Some troubles arrive with the weather. Certain plants have built in susceptibilities to certain pests and diseases. As with people, the natural decline of aging weakens defenses and aggravates all kinds of issues, whether a plant’s life span is as short as a summer season, like a tomato, or centuries long, like a redwood.

Engagement with the garden as plants cycle through their seasonal changes — “the footsteps of the farmer” — is the best defense against problems of all kinds. An attentive gardener can remedy problems in their early stages and, more important, has fewer problems to begin with.

Insects and diseases are opportunists. They take advantage of plants compromised by either human-induced or natural phenomena. Plants can be stressed by being situated in the wrong place or being improperly cared for — given too much attention, for example, or not enough — or by acts of God: torrents of rain, drought, heat, and the unseasonable late frost.

Engagement with the garden is the best defense against problems of all kinds. An attentive gardener can remedy problems in their early stages and, more important, has fewer problems to begin with.

Borers attack elderly fruit trees, drought-stressed trees, and sun-stressed bark. Killing borers does nothing to resolve the underlying problem. Aphids enjoy succulent new growth from too much fertilizer or an especially rainy spring. Aphids also attack plants like pansies and Swiss chard at the end of the season as the plants go into a natural decline. Cherries, apricots, and plums are disposed to weeping sap, called gummosis, but water-logged soil promotes it with a vengeance. Mildew prefers certain varieties to others and is most active when these plants get too much shade, or during cool, dry conditions. Fire blight is a bacterial disease that enters through blossoms and causes stems to wither. It attacks apple relations and is promoted by extreme temperature fluctuations from day to night.

Gardens don’t need to be pest free. Having a balance of insects in the garden is okay and even desirable. A garden that maintains some prey attracts beneficial predators. Small outbreaks of ash whitefly on citrus, for instance, encourage their Encarsia wasp predator to stick around. As long as both survive in the landscape, the small populations of whitefly that spring up from time to time are naturally controlled. It’s an elegant system.

In many instances, minor incidents of disease do little harm. Disease problems often decline as the weather becomes more congenial and soil conditions are rectified. It’s easy enough to prune out diseased and infested foliage and remove infected fruit as you come across it, especially if your trees are small. And pesticides, even the least toxic, can harm beneficial insects in the garden.

When encountering trouble, don’t panic. Most plants can sustain some damage. Proceed as you do with pruning: evaluate the situation before taking action. Run through a checklist. Is the problem stable or getting worse? Is the plant compromised by an environmental condition like weather, drought, or too much shade? Is that condition temporary or permanent? Is it something you can fix, like your watering practices, or is the problem caused by a larger issue that is out of your hands, like irregular weather patterns?

When you address root causes, so to speak, the secondary problem often resolves itself. If you can’t fix it, say, by pruning up trees to bring sun into a shady area, or because the plant is too big to move to a more favorable location, the problem is sure to continue. Personally, I find these constant battles wearying. The very best lesson I learned in all my years of nursery work is this: eject the troublesome, and install plants that want to live where you want to put them.

You can probably relax if only a small percentage of the fruit or foliage is affected, the tree is otherwise healthy, and the problem, whatever it is, doesn’t seem to be getting worse. When do you call in the big guns? I rarely do. A spray bottle of anything offers support but only solves part of the problem.

Some garden events fall under your control and some don’t. Cursing the weather is a pointless exercise. As I write this, it rains unceasingly on my blooming Friar plum. It’s cold out there. Not a bee in sight. It goes that way sometimes. That’s farming, and one reason I’m a gardener, not a farmer. Other things being equal, the most appropriate action is often acceptance. Let Nature take her course. Next year provides a new set of headaches, and a new set of rewards.

Aphids. Aphids are small sucking insects that come in a rainbow of colors. On fruit trees, they are most commonly green and black. Aphids gather in what seems like an alarming abundance, usually in spring, and feed on newly emerging foliage. This foliage grows out to be twisted and deformed and is commonly confused with peach leaf curl. Aphids secrete a sticky substance called honeydew that attracts ants. Ants corral and farm the aphids like milk cows and fight off aphid predators. Aphids especially enjoy the succulent spring foliage of plum trees but are a common problem on other fruit trees, too. They prefer lush growth, the kind promoted by abundant spring rains or the use of certain types of nonorganic, fast-acting fertilizers.

Many predators go after aphids. If you unfold a curled aphidy leaf, you usually see these insects at work. Tiny, gray, puffed spheres are aphid carcasses that hosted the egg of a predator wasp. Little red and black “alligators” are baby ladybugs and big aphid eaters compared to the charming and more familiar adults.

Don’t bother with packages of ladybugs. Sellers collect and remove hibernating ladybugs from native habitats. When you release ladybugs in the garden, they’re in a migratory mode and fly away. Let predators come in on their own. If you have a sizable population of aphids, they will. Washing aphids off with water is as effective as any kind of organic or chemical spray, but definitely optional. Aphids are active only two to three weeks before they move on. The deformed foliage they leave behind looks worse than it actually is.

Wooly apple aphids. Wooly apple aphids are a different story. These cottony white aphids attack apple trees and apple relations like pears and quince. These aphids stay put. Spraying with horticultural oil kills surface insects — not a bad idea — but wooly apple aphids make galls in both roots and stems and live inside plant tissue where you can’t get at them. If practical, cut out smaller infested stems when you spot them. A mulch of worm castings improves the overall health of the tree and may encourage the insects to go elsewhere. Systemic pesticides that travel through a plant’s system to control pests are dangerous for people and compromise the health of plants. Nor are they particularly effective. Never use systemic pesticides on food plants — the poison travels through the plants and into the fruit. A plant with wooly apple aphids can live a long, long time if you keep it healthy otherwise.

Scale. The symbiotic relationship between barnacle-like scale insects and their ant protectors can be intractable. This requires additional attention like manual removal, targeted organic pest controls, and applications of worm castings. But even for scale insects, resolving the stressors that invited these scaled insects in the first place makes the most difference.

Leafcutter bees saw perfect circles from foliage to use as nest packing and are important pollinators. The plant doesn’t suffer. Spiders, even black widows, do no real harm and a considerable amount of good. Whitefly and housefly populations explode when people routinely spray around the exterior of the house to kill spiders. When we offered this no-spray advice at Scenic Nursery the pest control companies cried foul but couldn’t manage either fly population with pesticides once the spiders were dead. Live and let live. Chemical controls provide short-term solutions before insects develop resistances, but in the final analysis leave us worse off pestwise, degrade the environment, and affect our health.

When we lend an active intellect to the garden, it responds in kind.

An elaborate dance is at work with a beauty, order, and intelligence of its own, of which our understanding is limited. We, too, contribute to the cosmic scheme of things, as much a part of that order and intelligence as a bird or an apple tree. When we lend an active intellect to the garden, it responds in kind.

Use pesticides — especially the organics — when you need to, but never regard a pesticide as the entire answer. The best approach is to watch the whole of what goes on in the garden, support the impulse toward health and life, adopt a philosophical attitude, and allow events to unfold. It helps to develop more tolerance for imperfection and an occasionally reduced harvest. We can cut the apple around the odd codling moth. Good plant health and an environment in ecological balance is the first and best defense against insects and disease.

In many natural environments, a layer of nutrient-rich duff of decaying leaves and debris builds up on the surface of the soil. This layer benefits plants for numerous reasons. Microbial activity as leaves decay aerates and enriches the soil. Microbes also boost overall plant health because of their probiotic relationship with roots. In addition, decayed plant material reintroduces nitrogen and provides other nutrients to the soil. The duff layer slows the evaporation of water. It keeps roots cool and functioning efficiently. A surface mulch of organic material does the same thing.

Mulch is a classification, not a specific material. Any covering laid on the surface of the soil is called mulch. Sheet plastic, sand, and stones are sometimes used as mulch, though I don’t recommend them. Bagged products from the nursery, organic matter like leaf rakings, and chipped-up trees make great mulch.

Organic mulch has every desirable consequence. Surface mulches reduce the need for too-frequent watering. A mulch at least two inches thick slows the evaporation of water from the soil and helps any type of garden soil stay more evenly moist. As a top dressing of organic matter breaks down, it improves tilth and the overall health of the soil. It improves the friability, or looseness, of clay or compacted soil. And mulch just looks nice.

In any type of soil, mulch breakdown helps a plant gain access to soil micronutrients, such as iron, that it might have a hard time getting otherwise. If plants like citrus show nutrient deficiencies, mulch should be a part of the remedy. Mulch keeps roots warmer in winter and cooler in summer. Mulch attracts earthworms to the loamy soil developing beneath. It prevents weeds from competing with root systems.

Compost makes itself. Any household with a little outdoor space can take advantage of a compost bin. My square stacking bin has a lid that keeps the mammals out. More people should avail themselves of this nutrient-rich, free, easy, wormy, benign, something-out-of-nothing resource that benefits almost everything in the garden. Homemade compost is a far better product than anything a nursery sells in a bag. Plants love this stuff.

To make compost, pile moist or green materials like kitchen scraps and fresh garden prunings into the bin with dry materials like fallen leaves, shredded paper, or crumpled newspaper in roughly equal proportions. Keep wet and dry materials piled alternately and airily. The finer the material, the more quickly it degrades. If the pile gets too goopy or begins to smell, aerate it with dry material. If it gets too dry in summer and stops cooking, add a bucket of water. Cool weather slows the whole process down. That’s all there is to it.

I keep a small bucket under the kitchen sink, lined with a folded piece of newspaper. Into it I deposit a daily supply of compostables — kitchen scraps and paper, everything from toilet paper roll tubes, coffee grounds, empty seed packets, worn-out cotton T-shirts, egg shells, grapefruit rinds, and onion husks — before dumping it in the compost bin outside. Nonwoody outdoor debris, such as perennial prunings and leaf rakings, go into the outside bin, too. While there is minor controversy about the efficacy of using paper in compost, most agree this practice is safe.

To make compost, pile green materials like kitchen scraps into the bin with dry materials like fallen leaves in roughly equal proportions.

Green waste from a single household makes a sizable contribution to the waste stream. Every solitary compost pile goes a long way to help control the aggregate costs, both fiscal and environmental, of collecting and driving our green waste to the local composter/garbage dump. As good as we might feel about civic recycling, better — it seems to me — to keep as much of our waste as close to home as possible. Better still to use the alchemy of microbes and time to degrade our refuse and spread it enrichingly throughout the garden.

Compost takes care of itself until the bin will hold no more. Then, devote a day to a big compost harvest. Set the undecayed material from the top aside on the lawn and shovel out the compost from the bottom of the bin. The last time I did this, I collected ten cubic feet of fluffy, earth-fragranced material that I deposited directly into my raised vegetable beds. The broccoli sure liked that. Compost is great for fruit trees, too. There is never enough compost. Dole it out to your highest plant priority.

Landscape fabric and sheet plastic, even products with perforations, used under layers of mulch are counterproductive. These products interfere with the water and air absorption roots need to be healthy. A barrier of landscape cloth also keeps the beneficial effects of mulch as it breaks down from improving the soil. And it adds more useless plastic to our already plastic-saturated world.

Landscape fabrics don’t even control weeds very well. As chipped bark, leaves, and garden debris accumulate on top of these weed barriers and decompose, weeds grow in the layer of organic matter that develops there. If mulch laid directly on soil is at least two inches thick, the few weeds that grow through are easy to remove.

Once established, fruit trees usually get the nutrients they need from the soil. Fertilizer is optional for most established fruit trees with the possible exception of persimmon and citrus. Mulch alone often rectifies nutrient deficiencies, and mulch can be fortified with manures or used in conjunction with fertilizer. Organic sources for nitrogen like organic fertilizers, manures, blood meal, and fishmeal release more slowly and last longer, and they preserve earthworm populations.

Plants pick up nutrients from fall fertilizer applications while the soil is still warm. These nutrients provide a kind of savings account for the tree and become available when growth begins again in spring. Spring fertilization is less effective because plants can’t take up nitrogen when the ground is cold.

Mulch benefits fruit trees. Use it.

Be aware that soil products at the nursery labeled “organic” are usually organic in the biological sense and not organic in the way most of us use that term; that is, certified. Soil products aren’t regulated like food, but they don’t necessarily contain anything harmful. Soil companies list product ingredients in order of decreasing quantity on the bag.

I evaluated my gardening dollar and realized I spent fully 80 percent on surface mulches compared to the 20 percent on plants and everything else. That actually works out about right. Buy as much top dressing as you can afford, or find out if a local tree pruner will deliver chips for free. Some do.

Only Dr. Gordon Frankie of the Urban Bee Project at University of California, Berkeley, lacks everybody else’s enthusiasm for mulch. Mulch makes life difficult for ground-nesting bees. Bees are vital pollinators on our garden planet. Bees are endangered. Our lives would be grim without them. Do these bees a favor. Target your mulch where it’s most useful and leave at least half of your ground bare to accommodate the bees.

Every fall, I like to apply a thick top-dressing of a soil amendment that contains fifteen to forty percent chicken manure around my fruit trees, a combination that provides both mulch and fertilizer, the only fertilizer my fruit trees get. At a depth of at least two inches and spread to the perimeter of the tree canopy — called the dripline — this application carries a fruit tree to the following fall. The mulch advisors say keep mulch away from the trunk. This is probably a good idea. Try. I’ve never been able to do it. As soon as I water, the mulch is back where it shouldn’t be. I never found this made much difference, maybe because the mulch I use dries out so quickly.

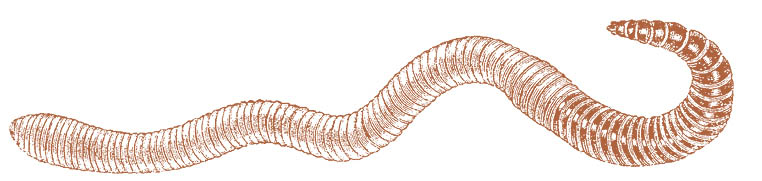

This section leaves the solid ground of hard science to enter the realm of anecdote and personal experience, but the news is too good to omit. When a plant is stressed and bug-ridden, once the environmental causes of that stress have been identified and corrected, I often recommend a top dressing of worm castings. Worm castings are like acupuncture or homeopathy for the plant kingdom — they work in ways that are subtle, mysterious, and unlikely. Plant pathologists remain leery and, in fact, might laugh you out of town. In my experience worm castings are hugely helpful, especially with soil diseases and all sorts of insect infestations.

I recommended worm castings to hundreds of customers, saying just what I say here. It sounds crazy. Try it. Report back. They did. Worm castings worked for them, too. Not always. Castings may differ batch to batch depending on how old they are and what the wigglers eat. Worm castings help only if other environmental factors, like water issues, are resolved. Even so, they seem to provide benefit enough of the time to assure me that my experience has valuable general applications.

Worm castings are essentially worm manure. Red wigglers digest food scraps and junk mail into a dense and odorless compost that plants adore. You can easily make worm castings at home in a worm bin. If you’re not up to tending livestock, you can buy a bag of worm-free worm castings at most retail nurseries.

Worm castings are like acupuncture or homeopathy for the plant kingdom — they work in ways that are subtle, mysterious, and unlikely.

Worm castings are rich in nitrogen, growth hormones, beneficial microbes, micronutrients, and minerals. The who-knows-what that makes plants resistant to insect pests and disease is more concentrated in worm castings than in wormy compost. Because worm castings are more expensive, I use compost more generally and reserve worm castings for use as preventive medicine or when there’s a specific problem. You don’t need much. Top-dress a plant a half-inch deep out to the dripline. Reapply every six months or as needed.

Most remarkable is the castings’ proven ability to control soilborne fungus disease and its ability, as yet unproven, to help control insect infestations. Worm castings seem to accomplish this systemically — from the inside out.

Maybe worm castings boost the overall health of soil, which has a positive effect on plant immune systems much the way a substance like brewer’s yeast boosts immune systems in people. Vermiculturalists speculate that the chitinase enzyme in earthworm castings degrades chitin. Because insects, like ants, have exoskeletons made of chitin, they avoid a top-dressed layer of castings around a plant and seem to stay away from the plant as well. This sounds plausible. It may or may not be true. Maybe worm castings complete some missing link in the environment that makes everything work better. The reasoning is unclear and in dispute, but there are several ways this might work.

Ants have a reciprocal relationship with aphids and scale insects. Ants fight off predators in exchange for the sweet and sticky honeydew these insects produce. If worm castings keep ants away, the absence of ants might give natural predators already present in the environment the opportunity to go after scale insects. Or possibly, the next generation of scale insects present when castings are applied may prove to be weaker than the parent generation, and more likely to die off. Treated plants might also be less attractive to invaders because, overall, they are healthier and have better defenses than weakened plants do.

The ten-foot grapefruit tree that grows in my parents’ yard was riddled with cottony cushion scale insects, white and puffy insects especially fond of citrus. Insecticidal soap killed them, but new scale came right back. Oil sprays kill scale insects only in their soft-bodied crawler stage. Once the insects develop protective cover, they’re safe. Ants ran up and down the trunk. Black sooty mold grew on the honeydew secreted by the scale and covered foliage and fruit. From a practical standpoint, the tree was too big to keep spraying. Nothing conventional did the job, but I had long heard rumors about worm castings from a variety of sources.

I put a half-inch layer of worm castings under the tree. I layered two inches of bagged mulch with 40 percent chicken manure on top of that. In six weeks, the scale had all but disappeared. New foliage popped out, bright green with a healthy shine. Now, I top off the mulch once a year with chicken-rich soil amendment and top-dress the plant with worm castings every six months or so. The tree radiates health. It looks better than ever — robust, healthy, lush, and green. Are the castings responsible? I couldn’t tell you, but I won’t leave them out of the mix.

The caterpillars that tunnel through apples are the larvae of codling moths. Codling moth control requires a multifaceted approach. Even then, prudence makes peace with the idea that you never get them all and that more moths are on the way. Codling moths fly in from other locations all summer and overwinter in fallen fruit. By far, sanitation is the most effective means of codling moth control. Dispose of fallen fruit. Don’t put infested fruit in the backyard compost pile.

When the Berkeley Horticultural Nursery apple tree had reached age seven, nearly half the crop showed sign of codling moth. I thinned each clump of apples to one lone fruit so caterpillars couldn’t travel fruit to fruit. I removed fruits from the tree that showed signs of infestation, the “dimple” where the hatched caterpillar drilled in. In this case, I sent a heartbreaking 40 apples from my smallish apple crop to the nursery green bin. At that point, I closed the barn door by applying a half-inch layer of worm castings. The following January I applied another. Nothing else changed.

By the next fruiting season, the tree showed no evidence of codling moth at all. In subsequent years, I repeated January and June applications of worm castings. I always removed one or two infested apples, but we never again had a problem like we had that one bad year. It’s important to note that the tree is small, so I removed occasional wormy apples as I came across them, and that our tree was otherwise cared for and in good health. Except for the addition of worm castings, nothing else about our care of the tree had altered. This experience by no means represents a controlled experiment. I can’t say for sure that worm castings were the magic ingredient, only that it looks that way to me.

Codling moth larvae create wormy apples. Eradication is difficult because the moths fly in all seasons.

Used as part of a wider program, traps provide some control of codling moths in isolated trees. When you read the fine print on the boxes, however, you learn that the real purpose of traps is to monitor insect populations. Barriers like paper bags or nylon stockings around individual apples are surefire, but way too much trouble for a gardener like me.

Keep things clean. Monitor and remove infested fruit and fallen fruit. Keep the tree healthy with adequate, not excessive, water and apply a layer of organic mulch. Plant diversity is an important part of pest control. Attract beneficial Trichogramma wasps by planting plants with umbel flowers like alyssum, dill, parsley, and yarrow. Unfortunately, because codling moths fly all summer, winter dormant sprays of horticultural oil offer little benefit in their control.

Colleagues and customers continually report worm casting success in the control of scale insects, aphids, wormy apples, and the mealy bugs that live not only on plants themselves but are shot through the soil of plants in containers. Even the thrips so ubiquitous in the Bay Area appear to avoid plants treated with worm castings. A top dressing of worm castings works enough of the time to make it worth trying. If they do little else, worm castings will give your plants a boost. For me, they seem to work as the most simple, noninvasive method of insect control I ever tried.

My young Sierra Beauty apple finally produced a decent crop of ten. Delighted, I monitored and admired my beautiful apples summer and into fall. One by one, birds picked off the first nine. I found them either still on the tree or scattered around the garden, not near ready, and rotting with one peck each. All the same, I like the animals. And they are only being what they are — hungry animals. By late October, when I went out to pick the last remaining apple, finally ripe, it was gone without a trace. Probably a raccoon.

My friends the Sinarles used a carbide gun, a device they called the “crow popper” in their almond orchards in Ripon, California. Every twenty minutes or so this device fired a blank and the birds scattered.

“You got used to it after a while,” Debbie said.

Evidently, the crows did, too. Now and then her dad went out with an actual shotgun, killed a few crows, and hung them by their feet from the barbed-wire fence to prove he meant business. Your suburban neighbors would doubtless discourage this method of bird control.

Alternatives exist for dealing with marauding animals, just not very good ones.

Mylar bird scare tape, available at your local nursery, hung above and around the trees affords fruit some protection from birds. This material flashes in sunny commercial vineyards as the grapes begin to ripen. Farmers wouldn’t waste time with scare tape if it didn’t do some good. Hang up the tape shortly before your fruit begins to color. If birds have discovered your fruit, it’s too late. The tape evidently works as a confusion device. Birds don’t know if the tape is safe and tend to stay away. I attached ten-inch strips of the Mylar with packing tape around the top of a six-foot bamboo pole, like a maypole, and stuck it into the ground in the middle of the plum tree. Remove the Mylar when the crops are in. Birds learn to ignore flash tape if you leave it in place.

A barrier of net most reliably keeps birds off fruit, but net carefully. If you want to feel like a human monster, trap a bird in a bird net. Honestly, I’d rather lose the apples, but birds get all the plums, too. Small trees make netting a practical possibility. One fed-up fruit grower near Fresno grows his fruit trees inside a large mesh enclosure.

Diversion is an appropriate tactic. My neighbor Ted told me that birds wreak havoc with his grapes but leave his peaches alone. I expect the birds just like grapes better.

Just grow more fruit. That way, they can’t possibly get everything.

This year, I carefully netted my 15 Friar plums, the total crop from a rainy spring. No problem with birds, but a raccoon worked around the clothespins and twist ties. It got away with ten of my plums without much disturbing the net. Raccoons have nearly opposable thumbs and often outsmart us. Deer eat fruit trees, even citrus. You can, of course, grow the trees over the heads of the deer, but then the trees become a different kind of headache. Plant fruit trees in a place where deer can’t get at them, or put up a fence.

Customers report that squirrels can be distracted from ripe fruit with better snacks in a different part of the garden. Who can tell what motivates or dissuades a squirrel? Motion-activated sprinklers get good reviews. I just learned about fox and coyote decoys with furry moving tails. Perhaps these fake animals will stalk my orchard next summer. They might put off the gophers, but I doubt it.