“We abound in the luxury of the peach.”

— Thomas Jefferson

And so we arrive at our destination: ripe fruit. Efficiencies of scale allow a backyard orchardist to follow the day-to-day nuances of each fruit as it approaches ripeness. Sweet, ripe fruit, perhaps with a hint of acid for balance, perfectly textured, and picked at its prime is unlike fruit available any other way. The farmers’ market, a farm stand, the grocery store, or a fancy mail-order house can’t deliver fruit anything quite like it.

Only a home gardener has the luxury of learning the habits of individual trees; keeping them well pruned, winter and summer; thinning overproduction; keeping trees mulched and watered; nurturing them through weather calamities; coaxing them past insects and disease; and standing by them in lean years. The homegrown fruit that finally ripens has the opportunity to reach, if not flawlessness, then as close to perfection as we are likely to get. Production growers, however skilled, however conscientious, can’t give attention to one tree and one fruit at a time the way a home grower can.

The less fruit you have, the more important the following information will be. As abundance becomes the rule and you have fruit to spare, as you become better acquainted and more familiar with the fruit on your fruit trees, and as years pass, you develop a knack for the look and feel of ripe fruit, and harvest becomes second nature.

A fruit tree’s job is to make another fruit tree. Fruit develops around the stone or seeds to attract animals (including human animals) that carry it off to start a new life in a different territory. When fruit is ready for this journey, it loosens from the tree.

Every September, I offered slices of tree-ripe Golden Delicious apples to nursery customers, apples picked from my sisters’ Richmond tree that morning before I came to work. Many customers told me, “No, thanks, I don’t like Golden Delicious,” but I persisted. The shoppers turned from the four-inch perennials or the one-gallon shrubs, accepted a slice, absently bit into it, and almost without exception focused their entire attention on the experience of the fruit. They looked up at me baffled and pleased. It tasted so much better than they had expected. I can’t count the number of apple trees I sold as a result of these samples, only because I had allowed the fruit to tell me it was ready.

The Fuji apples on our little nursery tree colored up seductively long before they were ripe. Wait, I told my colleagues, who couldn’t help themselves and picked the apples anyway. They taste fine, one of them said, but he only cheated himself. Fine is fine, and about as good as a good apple from the store, but fine is a far cry from the flavor he could have experienced had he been willing to wait only three more weeks. Customers often complained of the blandness of apples, blaming the climate or the variety, when in fact they had merely picked the fruit too soon. In many cases, customers harvested these “bad” apples before they had a chance to develop much sweetness and the full complexity of their flavor. Some apple varieties need even more time. Tart apples, like Ashmead’s Kernel, mellow and develop their best flavor with storage.

Put your hand under the fruit and give it a gentle tug. Ripe apples release into your hand. If the fruit holds, leave it on the tree. With apples, the release is definite. With stone fruits, ripeness heightens color, aroma, and a barely soft feel, but they, too, release when they’re ripe. I once heard it explained this way: the tree gives you fruit exactly when it’s ready.

Because we left our fruit on the nursery Fuji so long, it often developed signs of a condition described as “watercore,” translucent areas in the flesh of the fruit where sugars concentrate, usually the result of a heat spell. In commerce, these extra-sweet apples are considered inferior and, if possible, segregated out as flawed. To remedy watercore pick the apples sooner or, in other words, before they’re ripe. A customer from Japan told me that watercore apples are prized there because of their extra sweetness. If you cut open a watercore apple in Japan, it’s considered good luck.

The best and really only way to get exemplary stone fruit is to grow your own, or talk a neighbor into doing this for you. In order to transport fragile apricots, for example, growers pick them too firm to bruise. Apricots ripen off the tree somewhat, but never as sweetly as they would have. I would go so far as to say this: unless the apricot for sale is in close proximity to the apricot tree the apricot came from, don’t bother to buy it.

No fruit on any tree will ever be ripe all at once. In apricot season devote yourself to the apricots. Maximize your good fortune. Harvest and process your ripening fruit day by day, fruit by fruit. More than other crops, apricots tend to ripen together and in an exceedingly short window of time. Apricots taste best juicy, aromatic, and soft ripe. Keep an eye on color. Ripe fruit is a bright golden orange. It yields to the gentle pressure of your thumb. You learn to tell ripeness partly by the feel of the fruit. Apricots harvested at peak and left on the counter melt into a puddle in no time. Store ripe apricots in the refrigerator for up to a week.

As fragile as apricots, and equally as perishable, succulent, juicy figs travel poorly. Figs at market, rarely as ripe as they could be, can’t measure up to homegrown. Unlike apricots, figs stop ripening once they’re off the tree. The flavor never gets better if you pick a fig too soon.

All figs stick up vertically from branches as they develop. A ripe fig, rich and plump with sugars, bends the stem and pulls itself down by its own luxuriant weight. Ripe figs detach easily from branches. Go through the tree, and watch for limp stems and drooping fruit. Give each fruit a gentle squeeze; it should yield slightly to pressure and detach into your hand. Figs develop a subtle intensity of color as they ripen; dark figs are rich and dark, and light figs brighten, but don’t depend on color for ripeness.

Figs taste even better if they degrade a bit. Figs that begin to dry on the tree will shrivel at the stem, an indication of intensified flavor. To dry figs, let them fall naturally, and remove them to a drying rack in a place where they’ll be safe from animals and insects. My friend, Margaret Davis, dried figs in the rear window of her Toyota. Most figs produce two crops. A small spring crop, called the breba crop, grows on last year’s wood. When you generate new wood by vigorous winter pruning, you generate a more significant summer crop. Figs fruit mostly on new wood. No pruning means fewer figs. Prune figs whenever they look like they need it. While you may lose some breba figs with summer pruning, the resulting fruitfulness more than makes up for any loss.

A fallen fruit or two beneath a tree in high season indicates the time has come to attend to the fruit that ripens in the canopy above. A feel for ripe stone fruit comes with experience. You want to get that fruit before it hits the ground. Cherries are relatively sturdy, or transportable, compared to other stone fruits. Time it right, and you find cherries of excellent quality at markets and along the roadside. And a good thing, too — the birds probably ate all of yours.

Cherries, plums, pluots, peaches, and nectarines develop a depth of color as they ripen. Ripe cherries and other stone fruits soften slightly when ready to eat. With cherries, test for ripeness by tasting. You’ll soon know by color and feel which cherries are ready to pick. Leave too-firm stone fruits on the tree a bit longer. The flesh of ripe stone fruit has a bit of give. Richness of color helps indicate ripeness as you look at the fruit in the tree. Ripe fruit looks ripe. Ripe fruit is ready to let go.

Ripe fruit also smells ripe. Peaches and nectarines in particular are highly fragrant when they’re ready. The aroma of ripe peaches and nectarines significantly impacts the experience of the flavor. Peaches and nectarines tend to ripen quickly over a couple of weeks. Compare one fruit to another while they hang on the tree. Compare riper fruit to fruit that is less mature. Some differences, like fragrance and coloring, will be obvious. Check for ripe fruit daily.

When my mother had access to peak prune plums, she halved and pitted them, then froze them in pie tins for use in future pies. These pies oozed cherry-pink sauce and were fat with plums that tasted like they were picked yesterday.

A Bartlett pear tree was already established near the patio when my aunt and uncle, Shirley and Bob Hess, bought their house in Portland, Oregon. Aunt Shirley liked the looks of the tree’s spring bloom and its bare winter branches. It provided needed shade from the western sun. A bonsai enthusiast and aesthetic pruner, Shirley trained the tree into an umbrella shape. She worked without a ladder and kept it relatively small, not allowing the tree to grow taller than the eave. The pears on this tree were consistently wormy, grainy, mushy, and inedible. She attributed this to climate or bad luck. The tree satisfied her aesthetics, so she left it in place.

What a pear does for itself and what we like to eat are separate issues. Pears don’t ripen to human satisfaction when left on the tree. For best success with pears, Shirley learned to remove them from the tree when they are mature but pre-ripe, and allow them to finish their ripening inside on the counter. She ate good ripe pears from her own tree for the first time in thirty years. She also made pear chutney.

“It was excellent,” she said.

Like apples, pears, too, release their fruit to the farmer.

This pear advice comes from H. P. Books’s out-of-print Western Fruit, Berries and Nuts by Lance Walheim and Robert L. Stebbins: “To harvest pears, lift up fruit until the stem separates from the spur; do not pull or twist. If the stem does not break easily from the spur, allow fruit to ripen for a few more days.”

Pears are classified as summer pears or winter pears. Summer pears ripen in early August. While a few other heirloom summer pears are still in cultivation, the summer pear you’re most likely to encounter is a Bartlett. As summer pears mature, they brighten a little on the tree. Summer pears aren’t stored the way winter pears are. When they begin to color and separate from the spur when lifted, bring them inside to a coolish place below 75°F to ripen for a few days. The brighter the yellow, the softer and sweeter they become. Some people prefer pears firmer, some softer and sweeter. Watch the color of the skin. Once ripe, Bartletts keep only a day or two in the refrigerator.

Winter pears begin to ripen in September. Anjou, Bosc, Comice, and other winter pears, require storage for two to six weeks of chilling at a temperature below 40°F, either in refrigeration or in a cool place like a garage or basement, before you bring them out to ripen on the sink.

Unlike apples, the shelf life of a ripe pear is quite short. Pears ripen from the inside out. By the time the outside of a pear appears ripe, the flesh inside has gone to mush. Most experts agree that the best time to eat a pear is when the flesh of the fruit gives a bit to some gentle pressure at the stem end. Eat pears as soon as they’re ready.

Harvest Asian pears as you would apples.

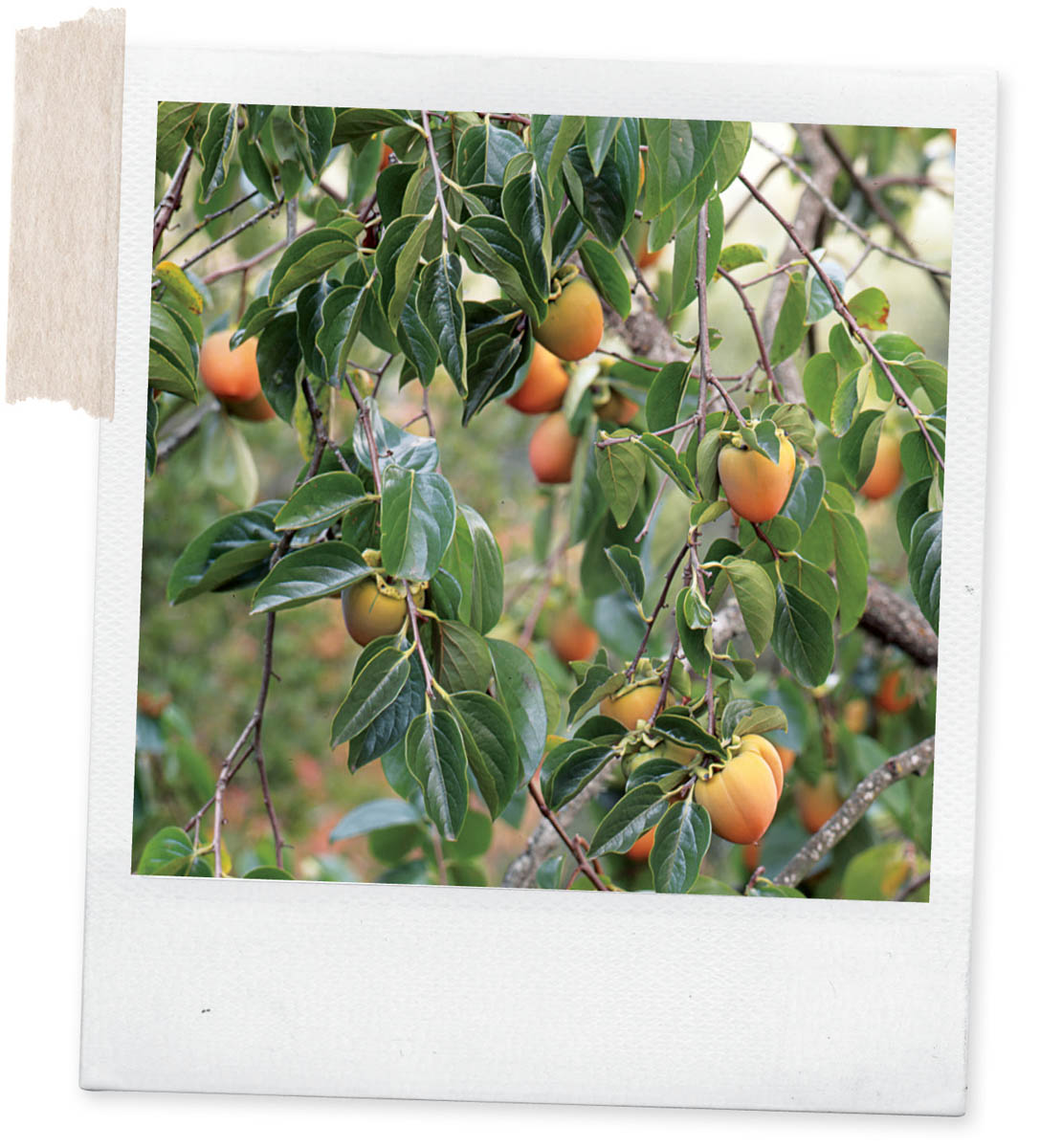

The most common variety of the astringent persimmon is called Hachiya, a large, handsome orange fruit; it has an acorn shape with a pointy end. Astringent persimmons contain inedible tannins that dissipate as the fruit overripens to a soft, very sweet state just short of fermentation. Eat astringent types when they’re overripe. Believe me, you’ll be sorry if you eat a persimmon before it’s ready. A ripe astringent-type persimmon is a rich, deep orange color with maybe some black streaks.

The astringent persimmon should be soft and collapsed within its skin. This process best occurs inside on the kitchen counter, rather than outside on the tree. Let fruit on the tree color to the stem, then cut the persimmons from the tree using shears. Be gentle with cut fruit; it’s prone to bruising. Get to your persimmons before the birds do. My mother — the fruit-eating expert — froze gooey-ripe halved persimmons and ate them from their skins with a spoon, partially thawed like sherbet. Like other fruit, ripe persimmons eventually release from the tree, but by that time they are too ripe to be useful except to foraging wildlife.

Fuyu persimmons are smaller than Hachiyas and have a flat, squashed shape. These and other non-astringent persimmon types have fewer tannins and develop good flavor while still firm. Fuyus are most commonly used while still crunchy, before fully ripe, eaten in hand like apples or sliced into salads. They develop a full, even richer flavor if allowed to soften in their skin like Hachiyas. For backyard gardeners, this means expanded uses, a longer season, and essentially two fruits for the price of one. Like Hachiyas, let Fuyus color all the way to the stem, then cut them from the tree. Let them ripen to either firm-ripe or soft-ripe on the counter. Firm-ripe Fuyu persimmons have a strong orange color and feel firm in your hand. Fuyus keep up to four months if stored in cool, not cold, temperatures. For best flavor, keep them out of the refrigerator.

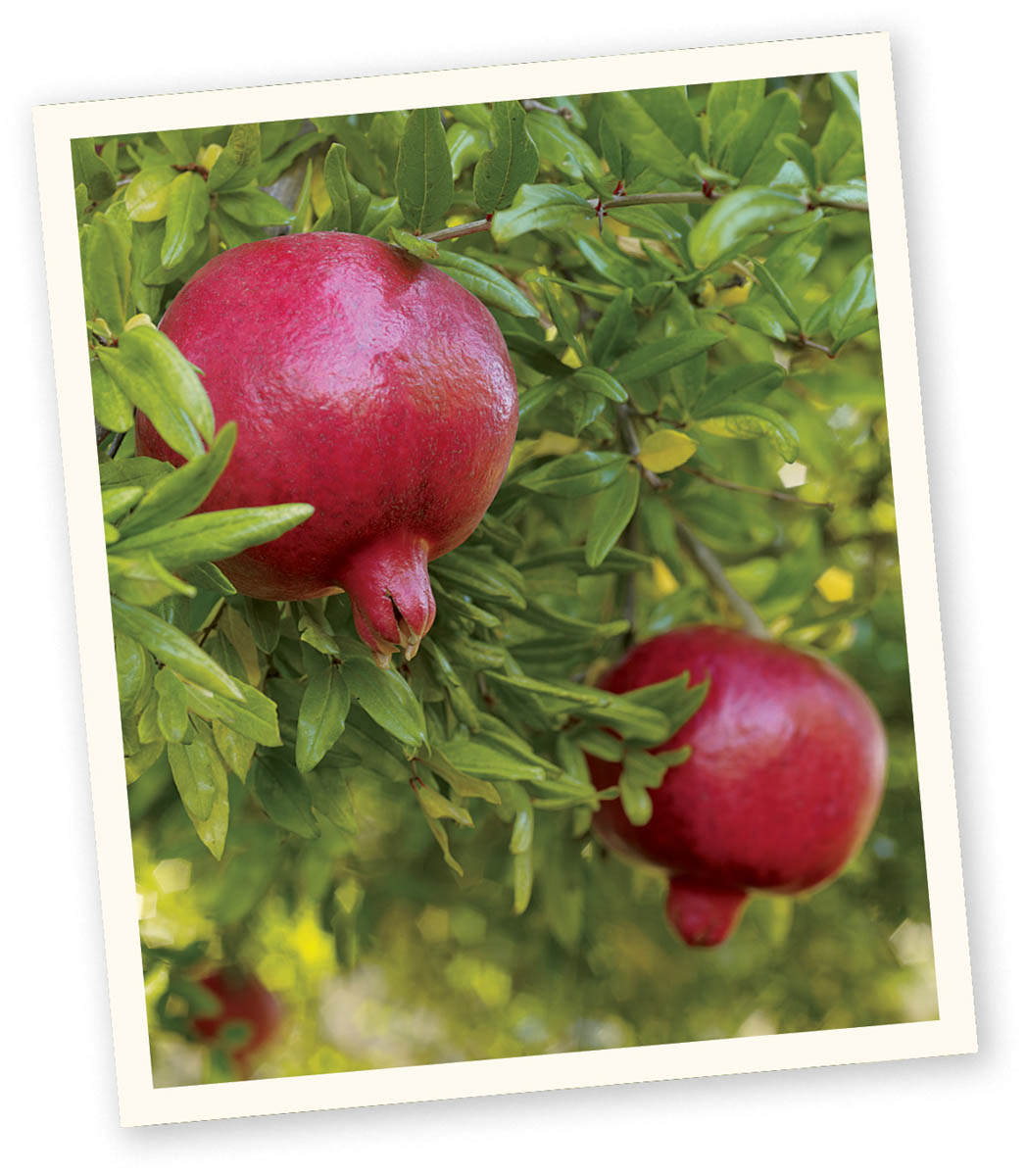

A pomegranate is ripe when the bright fleshy seed coverings — called arils — swell and push against exterior skin. These swollen seeds change the pomegranate’s shape from a perfect sphere to something more angular and obviously under pressure from inside. Core each end and score the crests of the angles for easy peeling. The fruit will break neatly apart. The leathery skin softens slightly and develops a shine. Like other ripe fruits, pomegranates feel heavy.

Ripe arils can crack the skin apart. In the home garden, cracks that expose the interior fruit are a sure way to tell if a pomegranate is ready to eat. Use cracked fruit quickly so the fruit doesn’t spoil. Uncracked pomegranates keep for a month or two when stored in a cool place or the refrigerator.

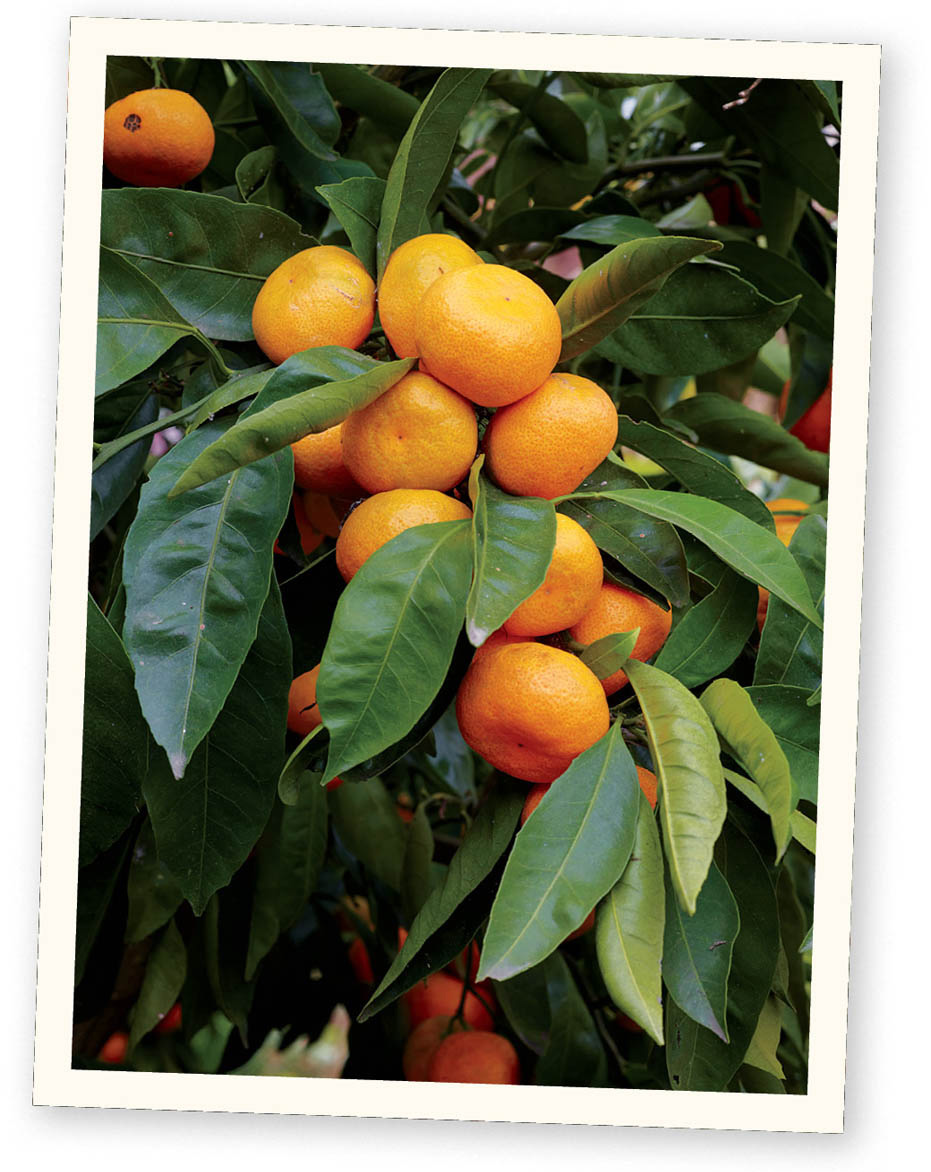

The only real way to tell if citrus is ripe is to taste it. Color isn’t a reliable indicator of ripe citrus fruit. Green fruit in warm winter climates can be ripe and tasty. Some citrus, once ripe, regreens as it hangs on the tree. As a rule, though, avoid green market fruit early in the season. However, I watch for regreened grapefruit late in grapefruit season around June and July; it can be especially sweet. Ripe fruit is weightier than fruit that isn’t ready; it has a nice heft. The peel of ripe citrus has a little give. Ripening times vary with locale. Improved Meyer lemons brighten in color when ripe. They set fruit and offer ripe fruit most of the year.

Citrus takes many months, often as long as a year, to ripen on the tree. Most citrus blooms and sets fruit about March and, depending on type, will be ready to use late fall and into the following spring. In Modesto, our dwarf Marsh grapefruit is twelve feet tall, up over the eave, and eight feet around — plenty big enough. It sets in April, and we leave fruit on the tree for fifteen months for maximum sweetness. The Satsuma tangerines and Washington navels in Modesto are ready in time for Christmas stockings. Cut the fruit, with the stem attached, from the tree. Stemless fruit tends to rot once picked. Citrus also stops ripening when removed from the tree. As a rule, citrus keeps best on the tree until you intend to use it. By the time citrus fruit freely releases from the tree, it’s often dry, pithy, and past its edible prime.