“Why not go out on a limb? That’s where the fruit is.”

— Will Rogers

At heart, we are still a nation of yeoman farmers. We owe our American backyards in part to Thomas Jefferson, who believed that small property holders with modest farms held a stake in the new republic and so propelled it forward. Citizens care for what belongs to them. As we build our lives to suit our needs and inclinations, we look to the future and to the health of the wider community. Small is a big idea. After World War II, this simple principle — that people invest in and build on what they own and know — led to Federal Housing Administration home loans, the GI Bill, and the greatest expansion of the middle class in our economic history.

When home gardeners borrow tactics from farmers, they get more than they bargained for — outsized trees and impossible quantities of fruit.

In this context, the American backyard and its attendant fruit tree reside firmly in our national DNA. No wonder we find home ownership, backyards, and fruit trees so irresistible. Walk around most established neighborhoods and you’re likely to spot a fruit tree in almost every backyard. Count the fruit trees in your own neighborhood.

We create our Edens in any corner we can find. If we don’t have land of our own, we borrow some. We establish community gardens. We find a place for a fruit tree to put down roots, even if we can’t manage to put down roots of our own. When we plant these trees, we dream of harvest and self-reliance. We want to free ourselves from pesticides and chemicals, and we want to control at least some of what we eat. We plant for flavor and quality, for fruit that tastes like the fruit we remember, or the rumors of fruit we’ve heard about from people who are old enough to remember. Perhaps most important, we plant for a simple and elemental domestic satisfaction — the singular pleasure of harvesting and eating food we’ve grown ourselves.

Let me begin by stating the obvious: a small fruit tree is easier to care for than a large one. One of the best reasons to keep fruit trees small is that big trees are so hard to care for. Big or small, most deciduous fruit trees need a few annual attentions to stay well-formed, healthy, and capable of producing and bearing fruit. Fruit trees require pruning twice a year. Fruit will need to be thinned and harvested. Pests and disease, if present, might need mitigation. None of these tasks is inherently daunting. In truth, these simple chores provide much of the pleasure of attending to a fruit tree.

The difficulty of seasonal routines, however, grows exponentially with the size of the tree. Pruning a small tree takes about fifteen minutes. Pruning a twelve-foot tree probably requires professional help at professional prices, and not just once or twice, but every single year.

Pruning a small tree takes about fifteen minutes. Pruning a twelve-foot tree probably requires professional help at professional prices.

Why, then, did we learn to manage fruit trees and prune the way we do?

Two centuries of industrialization changed the character of farming, and fruit growing was no exception. Tree size, spacing, and alignment adjusted to accommodate farm machinery. What we think of as classic fruit trees — the fifteen-footers — were winter pruned when the trees were dormant and a farmer had time to do it. Pruning trees to have open centers instead of a single “leader” allowed sunlight to penetrate the interior branches of trees that were shaded by an orchard around them. In the late 1940s, chemical pest control and soil enhancement with chemical fertilizers came into vogue.

These rote practices relied on machines and schedules to keep Nature in line. They promoted maximum size for maximum yield. Farmers need the yield on which their livelihoods depend. But when home gardeners borrow tactics from farmers, they get more than they bargained for; namely, outsized trees and impossible quantities of fruit. Most backyard growers don’t have the space or equipment to manage commercial-size trees, and even if they do, from pruning to harvest, the work these trees require overwhelms even the most dedicated family orchardist.

Old-fashioned fruit trees command garden space like, well, trees. Planting any tree in a small garden is not a step to be taken lightly, and fruit trees are no exception. Even if kept to only twelve feet — a tree that is twice as tall as you are with the crown of the tree at an equal spread — fruit trees create a substantial presence in the urban or suburban garden. The late and essential Henry Mitchell, Washington Post garden writer and author of The Essential Earthman, wrote in his essay “Bad Trees and Good Trees” that trees belong “in gardens in extremely limited numbers.” The italics are his. He makes a crucial point. Sun is worth preserving in a garden. People generally underestimate the ultimate size of a tree, a tree’s capacity to crowd its neighbors, and the amount of shade and debris that trees usually produce.

Many modern farmers now adopt the logic of growing smaller trees. The classic vase-shaped orchard tree is rightly and rapidly disappearing from commercial orchards for the same reasons it ought to disappear from our backyards: big trees are hard to care for. When you drive past orchards these days, you see short trees of all varieties planted in close proximity. What farmers do is only partially relevant to the home gardener, however. Home gardeners have different purposes from farmers, and different rules apply.

In most cases, reducing fruit production in a backyard tree is an excellent idea. People often radically underestimate the fruit-producing capacity of the average-size fruit tree and overestimate the amount of fresh fruit they actually use. A realistic appraisal of your fruit consumption is an excellent place to begin. Consider this: a twelve-foot apple tree — remember, that’s a small one, twice as tall as you are — can easily set fifteen hundred to two thousand apples.

To thin the fruit, you need to climb high into the tree. This fruit thinning will take a good bit of your spare time, if spare time is an option you can entertain. But let’s say it is, and you do. Apples usually set four to five fruits per cluster. You reduce the clusters to one apple each and bring your crop down to, say, six hundred apples. That’s six hundred Fujis ripe right around Thanksgiving.

Now, apples that fall to the ground may still be edible, but only if they have a soft landing. Collecting apples before they drop means climbing high into the tree again, over about a three-week period. Okay. You lose some apples to birds and codling moth. You’re diligent, though, and a member of a family of four. Let’s say you collect most of the remaining apples. A best-case scenario gives each person in the family one hundred and twenty-five apples apiece to use as he or she chooses, or about three per person each day over a period of two months.

Fujis are basically a single-use apple. They’re terrific, especially homegrown, and, as the apple people like to say, great for eating out of hand. They’re good keepers, too, meaning that their quality holds up well if you store them in a cool place like the basement or garage. To my taste, they’re a bit sweet for alternative uses like baking and applesauce. With one big tree, though, you have nothing but Fujis. You probably want to use them fresh. The people at your place of work will be happy to see you coming in with bags full of tree-ripe apples.

However, the more likely scenario is that you collect about sixty to a hundred smallish apples from the lower parts of the tree because you never got around to thinning them, and the crop remaining will fall to the ground to bruise and rot. You harvest low-hanging fruit, but midway through apple season, you tire of reaching higher and higher into the tree. The apples you don’t pick fall to the ground, creating an even worse codling moth problem next year as the caterpillars reproduce in the fallen fruit. Saddest of all, exasperated by these unending demands, when apple season is past, you’re happy to see it go.

One of my colleagues, Jean-Marie, told me of an ancient apple tree in his in-laws’ backyard in Utah. The tree had been neglected. Over the years, it grew to twenty-five feet high with an oaklike trunk, as tall as the sycamores that line streets of old downtown neighborhoods. Jean-Marie said that every October overripe apples, too far out of reach for harvest, rained from the tree with such force they exploded as they hit the ground. You could hear the explosions from inside the house, he said, where you safely retreated from the bombing fruit and the consequent mess and stench of hundreds of rotting apples lying worthless on the ground.

From a twelve-foot, thirty-year-old Golden Delicious apple tree in Richmond, California, my sisters fill the green bin three times every harvest season with wormy windfalls they can’t possibly use. They employ a long-handled tennis ball tosser called a Chuckit! to retrieve the apples from the ground, but this apple retrieval is still a huge job. If you have a troublesome tree like this, you can reduce the amount of fruit set by spraying the blossoms with water from the hose while the tree is in bloom. This halts some fruit production, but the tree still requires pruning and care. Nor does it address the problem of managing the fruit that remains.

Ripe fruit also expresses a very real urgency. Stone fruits like apricots, peaches, and plums have a much higher urgency score than apples. Most fruit crops tend to ripen all at once and not necessarily on a schedule that accommodates a busy life. In summers, my dad graded peaches to supplement his teacher’s pay. Free peaches came with the job. I well remember my mother’s misery, the swamp cooler blowing down the hall in the heat of August, as she worked morning to night for several days to can quarts of peaches before they went bad in the lug box.

And as much as we might like cobbler, how many of us are really prepared to process and clean up after a thousand dead-ripe apricots? One June, when I was a college student in Fresno, roommate Luann and I, short of funds, cooked apricots from a backyard tree every way we could think of, short of canning. We made pies, cobblers, syrup, quick breads, crisps, and jam. We used maybe an eighth of the crop and made ourselves sick in the process. The remaining apricots turned into a stinky, gooey, insect-laden fruit tar as they dropped and coagulated underneath the tree.

Proper pruning doesn’t just keep trees small; it limits crop size to fruit you will actually use. Home gardeners typically do better with reasonable amounts of fruit.

Fruit gone to waste is a heartbreaker.

Most nurseries offer fruit trees grafted (see A Brief Glossary) onto semidwarfing rootstocks. I give closer attention to rootstocks, grafting, and rootstock selection in chapter 2; just note here that dwarfing potential is the least important thing about a rootstock. People seek out fruit trees on semidwarfing rootstock with reasonable expectations of smallish trees. How mistaken they will find themselves to be.

While somewhat smaller than standard-sized fruit trees, many of these so-called semidwarfs grow rapidly to be at least two stories tall, three times too tall to be managed by the average five- or six-foot person. Fruit trees sold as semidwarfs require pruning for realistic size control. In fact, the term “semidwarf” is so misleading I wish I could drop it from my fruit tree vocabulary entirely. Semidwarf means only “smaller than standard.” If a full-size fruit tree is thirty feet tall, then a semidwarf might grow to be as high as twenty-five.

In contrast, genetic dwarf trees have their short stature bred into their genetic make-up. Genetic dwarfs aren’t grafted like semidwarfs. They grow on their own roots. On average, they stay between six and eight feet tall. When you breed a fruit tree for one quality, such as size, then other traits like fruit flavor and overall vitality become necessarily secondary. My dad planted a dwarf peach that grew to four feet tall with an elegant weeping habit. It produced stunning double pink blossoms, followed by fruit so bland and mealy that nobody bothered to eat it.

While a few genetic dwarfs produce fruit of admirable quality, they don’t offer much in the way of choice varieties or climate adaptability. There’s no such thing as a dwarf greengage plum, for instance. In addition, a dwarfed root system tends to compromise the overall health and longevity of the tree. A genetic dwarf variety of apple called Garden Delicious produces spritely fruit, but the tree lives only twelve to fifteen years.

Some fruit trees are available grafted on ultra-dwarfing rootstock. These trees stay quite small, four to six feet, but because of their extremely small root systems, ultra-dwarfing rootstocks present many of the same problems genetic dwarfs do in terms of short life and overall plant health. Bigger root systems make for healthier plants and better anchoring. Ultra-dwarfs require permanent staking so they don’t tip over.

You don’t need to buy dwarfs or ultra-dwarfs if you want small trees. Europeans have used pruning to keep ordinary fruit trees small for centuries. Take a visit to a historic garden in the United States, and you will discover that our own Founding Fathers often kept their fruit trees small. Once you understand the simple logic of pruning, keeping a fruit tree appropriately scaled is easy enough to do. In fact, regular pruning is the best way to control the size of a fruit tree.

Whenever I give a pruning talk, I repeat that statement to make sure nobody missed it, and so, here too, once again: regular pruning is the best way to control the size of a fruit tree. When tree size is a factor you control with pruning, your options change entirely. You can base your fruit tree selection on the single most important criterion — the desirability of the fruit. Resolve the size issue and one key issue remains: What kind of fruit do you want to grow?

Any type of deciduous fruit tree responds to the keep-it-small pruning treatment — the oldest heirloom or the most recent introduction. Choose whichever variety of apricot, apple, cherry, fig, quince, persimmon, plum, or pluot — a plum-apricot cross — is most ideal for your palate and your climate. Keep it small. Put away the ladder. You can plant more trees than you planned to, either singly around the garden, or in a hedgerow along a sunny fence, or even three little trees closely spaced and pruned to grow apart from one another (three fruit trees together where you thought you had room for only one). You can work fruit trees into an existing landscape. You can accommodate favorite fruits that need another tree for pollination. With attention to ripening times, you can harvest fresh fruit in reasonable quantities from your garden from late spring well into winter. Factor in citrus if you live in a citrus-friendly climate, and you can harvest fresh fruit from your garden year-round.

Regular pruning is the best way to control the size of a fruit tree.

How big should you let a fruit tree grow? And make no mistake, your fruit tree will grow if you do nothing to stop it. People are essential players in any fruit tree equation. Tree size is entirely your choice, of course. You can have a big tree if you want one, and the work that goes with it, too. To my mind, though, human-size trees are a better fit for both the garden and the gardener. Ed Laivo puts it this way: “A good height for your fruit tree is as tall as you can reach while standing on the ground.”

In the 1950s, my parents planted a Meyer lemon hedge in front of our Modesto ranch-style house and pruned it square. For as long as I can remember, we harvested fresh lemons from the front yard most of the year. Ripe fruit held reliably on the plants through the bloom cycle and almost as long as it took for the new fruit to begin to ripen again near Christmas. One of the advantages of life in a Mediterranean climate is the luxury of citrus in the garden.

Citrus is an evergreen tropical that doesn’t require an initial hard prune or routine pruning the way deciduous fruit trees do. It grows as a large, round fruiting shrub. Dwarfing rootstocks work well with citrus. In fact, citrus became a temperate-climate garden staple because of the success of dwarfing rootstocks. Standard-size citrus trees can get much larger, twenty-five feet high and as wide, and make, to my mind, a difficult proposition for a backyard plant.

Prune citrus if you want to. Shape citrus as you see fit. My parents’ Meyer lemons would have easily grown as tall as ten feet had they been allowed to do so.

For some reason, plant height confuses nursery shoppers. The yardstick of your own body should logically give you a sense of how tall things grow, but it doesn’t seem to work this way. The phenomenon is so common that it clearly has something to do with perception and not general cluelessness. Say the sign in a nursery says a plant grows to be eight feet tall. Most people take that information to mean that the plant gets to be a little taller than they are, whether they stand at five foot four or six foot seven.

Plant buyers need also bear in mind that, usually, when a plant grows to eight feet tall it develops considerable spread. Even people who have a reasonable idea about scale in their own gardens buy an unassuming plant in a one-gallon container, take it home, and set it two feet away from the fence, where it quickly overcrowds its designated space. From long experience, I know better, and yet, I still do this.

The problem was so widespread and severe, we posted signs around Berkeley Horticultural Nursery that marked heights at eight, ten, and twelve feet, so that customers would have some idea of what they were in for when we pulled a skinny little sapling from the bareroot bin. Some of my most important work in my many years of nursery employment has been not so much in providing plant information, but in pointing out height — ten feet is as tall as that eave. Once you get a real look at twelve feet, fifteen feet is quite a shocker. To compound this confusion, those of us in the nursery industry call a tree that grows to fifteen feet high “a small tree.”

The term “dwarf” also baffles plant buyers. Many people believe that a dwarf tree grows to the height they have in mind for it to grow. Most think a dwarf plant is very small, topping out at maybe two feet. Indeed, some dwarf plants do stay this short. Nevertheless, the term “dwarf” really addresses issues of scale when compared to the general species. Varieties of Acer palmatum, for example, the dwarf Japanese maple, grow anywhere from four feet to twenty feet tall. They are classified as “dwarfs” because of their thirty-foot-tall cousins.

When choosing citrus for planting, pick dwarfs that grow anywhere between eight and twelve feet tall, depending on variety. If you want to prune a citrus tree to correct the shape, summer is the time to do it. The evergreen foliage on citrus affords them frost protection that you don’t want to remove in winter. As described in chapter 3, ordinary heading and thinning rules apply. When pruning, be aware that the shrubby growth habit of citrus and its canopy of leaves protect tender bark from sunburn.

Once established, citrus in citrus regions manage some frost without much trouble, especially if the trees grow in protected locations like courtyards, or on the south side of the house. Every few years a killing frost rolls through some moderate climates. Damage from these frosts worsens dramatically when they follow a drought. Moist soil is a frost-tender plant’s best protection against bitter cold. If you learn of the possibility of an extreme frost, check soil for moisture, especially if it hasn’t been raining. Water if you need to.

When covering a plant to protect it from frost, the idea is to trap warm air around the plant as it rises from the ground. A temperature increase of a degree or two is often enough to keep plants from sustaining enough damage to kill them. Some people warm up their citrus by decorating them with Christmas tree lights. If the weather pattern is severe enough, you may want to harvest fruit so it doesn’t freeze.

Plant citrus any time of year into unamended garden soil. Evergreens don’t have a hard dormancy the way deciduous trees do and, because of this, are not available bareroot. Top dress with at least two inches of mulch fortified with chicken manure — like other fruit trees, citrus prosper with an application of mulch. In some regions, frost protection for the first three winters while the tree establishes itself is a worthwhile precaution. Cold hardiness varies within the citrus family. Mexican limes are far more frost tender than mandarins, for instance; and some, like grapefruit, have a greater need for heat. Check with your local nursery.

Citrus is a good choice if you must plant fruit trees in containers.

Provide citrus with regular deep watering, about once a week, especially early in the season if the rain stops and as the tree is flowering and setting fruit. Applications of fertilizer and mulch, or manure-rich soil amendment used as mulch and refreshed once a year, will improve the health of the plant, its frost resistance, and the quality of the fruit.

A fruit tree’s job is to produce an adequate supply of fruit, adequate being however you define it. My adequate can be forty. Your adequate might be two hundred. In spite of what you may have read, a fruit tree doesn’t need to look a particular way to accomplish the goal of meeting your needs, production-wise. Personally, I like a little elegance in my fruit trees, an occupational hazard of being an art major, I suppose. This proclivity is merely the way I think about things and has no real bearing (so to speak) on fruit production. Not everyone adopts this aesthetic, or needs to.

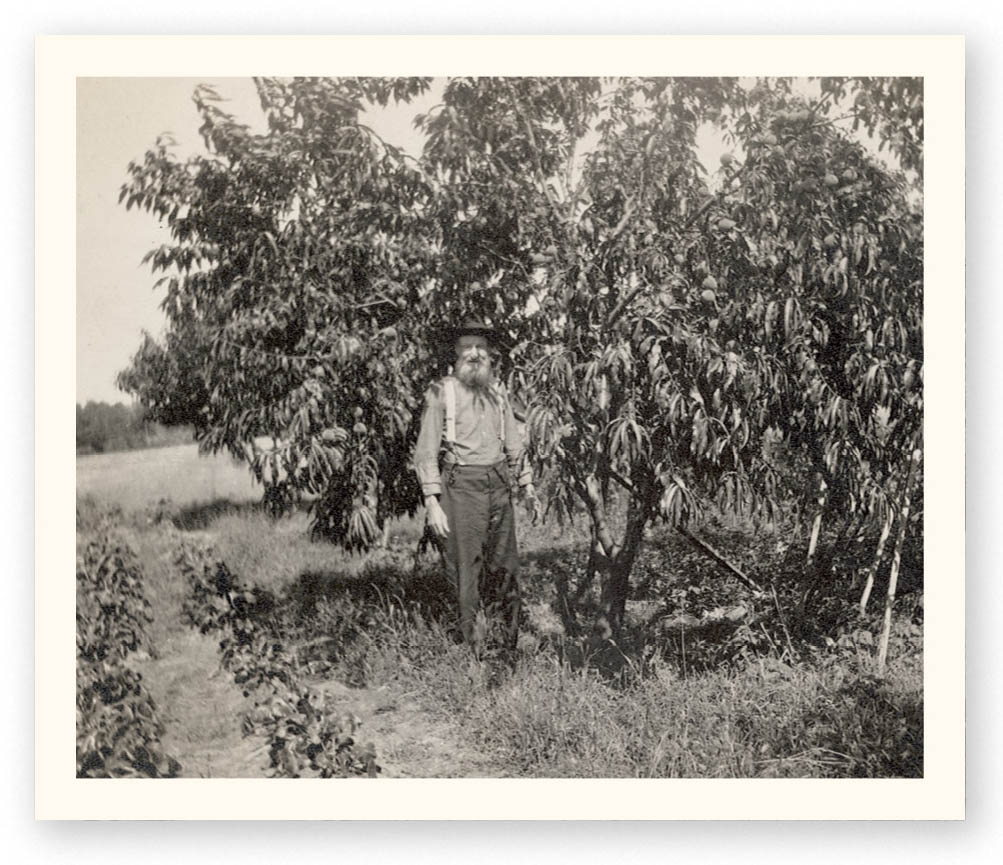

Steve Detherage worked with me at Scenic Nursery in Modesto. His grandfather was a farmer who, late in his life, lived alone on some acreage in California’s Central Valley near the town of Ceres. He kept a peach tree on the property long past its prime. Peach trees usually last only about twenty years. This tree was easily years past that. Over many seasons, the weight of the fruit cracked off most of the branches, one after another, until one last limb remained. This decrepit, lopsided tree bothered Steve a good deal.

“I work in a nursery, Grandpa,” Steve said. “I can get you a new tree.”

“No, thanks, son,” his grandpa replied. “Every summer, I get about eight peaches, which is as many as I care to eat, and every year, those peaches taste as good as any I ever had.”

We would be wise to abandon our conventional ideas about fruit trees and adopt this practical way of thinking. There are all kinds of ways to build a functional tree. My aunt Doris grew a Frankenstein’s monster of an apple tree in her backyard. The tree was at least thirty years old. Son Dan Nelson, a nursery wholesaler, took a chain saw to the tree when it got out of hand. Today, it looks like a giant slingshot with many horizontal fingers emanating from the ends of each fork, each finger a different variety, the grafting accomplished over a number of years. While hardly traditional, it serves a useful function: one tree, many varieties, a long fruiting season, and all within reach.

Dan is the first to say that the chain saw approach was a necessary consequence of overgrowth and neglect. There are “better” ways to prune trees, of course — methods that the tree can more easily manage. For one thing, small pruning cuts heal more readily than large ones. Timely and regular pruning creates more handsome specimens. Dan freely admits there would be more fruit if he “tried harder.” Still, I couldn’t imagine a better fruit tree for my ninety-five-year-old aunt and her purposes: Gravensteins for applesauce and pippins she could reach for her legendary pie.

One last odd example, a Santa Rosa plum, grows in the demonstration garden at Dave Wilson Nursery. Actually, this tree can’t be called a tree at all. It’s a four-by-four-foot fruiting deciduous shrub — bushy and flat-topped. It looks like any shrub you’d shear with hedge shears. In fact, it came to grow this way with aggressive shearing, an experiment to see exactly how far it was possible to push the small fruit tree concept. Pretty far, as it turns out. This fruit machine cranks out about two hundred and fifty plums per season, enough to provide all the Santa Rosa samples needed for Dave Wilson Nursery fruit taste tests.