“Look at this apple. It’s as pretty as a girl.”

— Overheard in Calaveras County at a Humbug Creek Farm cider pressing

“Quince,” we said, when a customer showed us the apple for identification.

“No,” she said. “It’s an apple. A good one.”

Unassuming and lopsided with yellow, flecked skin, and new to us, we sliced it up at the counter for a taste test. The sample had a complex and notable flavor, crunchy, aromatic, and sweetly tart. These apples grew in varying sizes on her tree, some quite large.

“An excellent baker, too,” she said.

In Berkeley, mild weather makes fruit growing a challenge. This apple belonged on our roster. By the time a second customer came in with the same mystery apple the following week, we had tracked it down — a low-chill, colonial variety from New Jersey called Yellow Bellflower. An apple so delicious it followed the homesteaders west.

The Yellow Bellflower apple is beautiful in bloom and so delicious that it followed the homesteaders west.

The first rule of fruit selection is this: plant fruit you like to eat. Different people have different preferences. Years of fruit consumption yield certain conclusions. Some people like achingly sweet fruit, or soft fruit, or balanced fruit, or fruit so tart it makes their hair stand on end. Decent fresh apricots are nearly impossible to find at the market. I have little memory of specifics, but I do recall the flat-out abundance of meltingly delicious, dead-ripe summer fruit in the San Joaquin Valley, passed around so freely it never occurred to me that I might one day have to live without it. Canners and bakers want to choose fruit suited to their purposes. Many great backyard varieties perform admirably in more than one role.

Many fruit tree planters have memories of a favorite fruit — the plum that grew over the fence from a neighbor’s yard, for example, or a great aunt’s apricots. If you have access to the actual fruit, try to get it identified at a farmers’ market or through your Cooperative Extension. Your fruit ripens the same time a farmers’ market has it for sale. Catalogs and websites offer great photos and descriptions for the would-be fruit identifier. Check a ripening chart like the one on the Dave Wilson Nursery website against fruit descriptions for timing information that narrows the field of likely matches, which is especially helpful if all you have is a memory of the fruit.

One very nice thing about growing small fruit trees is that you have room for more trees and can harvest small crops of different kinds of fruit June to December.

Your mystery fruit is unlikely to be a rare variety unless your tree is ancient or you have reason to believe your tree was planted by a fruit enthusiast who sought out exotics. Most of the time people plant what is commonly available, either through mail order or locally. They tend to keep planting common varieties that perform well where they live. A little historical research at an established nursery can probably help you determine best sellers around the time your tree was planted.

There’s nothing dull or uninspired about selecting common varieties if you like them, as you discover when you taste one fresh from a backyard tree. Ordinary varieties like Blenheim apricots and Santa Rosa plums become common for both their flavor and their reliable behavior. Fuji apples are popular for good reason.

Fujis define the perfectly sweet, juicy, crunchy apple. They keep well. Hot climates like the Central Valley in California are usually unfavorable to apples, yet Fujis perform well there. Provided the growing season is long enough and they get late summer heat, they’re fine in cool climates like the East Bay, too.

But don’t stop with Fuji. One very nice thing about growing small fruit trees is that you have room for more trees and can harvest small crops of different kinds of fruit from June to December. You can plant Cox’s Orange Pippin apples for fresh eating and Yellow Newtown Pippin for pie. Small trees and close planting create space for experimentation and for planting fruit on the endangered species list. There’s room for Yellow Bellflower. There’s room for a Hudson’s Golden Gem or a Wickson Crab.

A homegrown Fuji will be tastier than any Fuji you ever bought at the store.

Talk to local fruit growers, your friends and neighbors, and local nurseries. Seek out local fruit gurus. Stop at farm stands and farmers’ markets. Taste lots of different kinds of fruit, especially fruit that is locally grown. We perked up when we encountered the Yellow Bellflower because it was grown in the neighborhood. Ripe local fruit gives you the best indication of how that fruit will taste when it comes from your garden. Because you aren’t a farmer, you can attempt things that farmers can’t afford to try — wonderful fruit with a short shelf life like Gravensteins, or the achingly delicious Emerald Beaut plum that needs a pollenizer, and looks, well, homely and unappealing.

The quality of fruit you buy at the store is not a reliable indicator of the quality of the variety. Yellow Newtown Pippin apples show up in markets in September when they’re still green, literally green, in color and also not quite ripe. They have yet to develop the yellow blush that gives them their name and lets you know they’re ready. Golden Delicious apples, commonly found in grocery stores year-round, may taste bland from the store but really are delicious if you grow them yourself.

Classic varieties like Golden Delicious available for sale to fruit growers for years and years have proven themselves. Varieties with limitations tend to drop out of the marketplace. Plants cycle in and out of fashion just like clothing does. Heirlooms are the latest thing, but heirlooms aren’t created equal. Heirlooms are not worth growing simply because they’re heirlooms. Try the fruit first.

True, some heirlooms have been wrongfully cast aside, but sometimes they recede in popularity as a consequence of their flaws or because better fruit replaces them. What we know as heirlooms were once recent introductions. Floyd Zaiger, a modern Luther Burbank from Modesto, California, brings us plum and apricot combinations like pluots and apriums, and the peacotum — a plum, peach, and apricot cross — the old-fashioned way, by hybridization. Hybridizers develop new varieties with better flavor, texture, keeping qualities, disease resistance, and more climate tolerance. Modern apples like Braeburn, Fuji, and Pink Lady have exceptional texture, juiciness, and flavor and are well behaved in the garden besides.

In contrast, and in spite of glowing descriptions, very recently developed varieties lack real-life trials under a variety of conditions in ordinary gardens. If I’m stuck between two choices that sound good, I usually choose the more familiar, time-tested model. But that’s me. Reliability matters. Does this mean you should abandon a desire for the rare and unusual or recent introductions? Not at all. In terms of time and cost, taking a chance on an odd or new variety represents a modest investment — if you crave adventure and can afford the time and space. Fruit is an individual matter. Different people have different fruit growing objectives, different ideas about what tastes good and what sorts of imperfections they can tolerate, and different plans for the fruit.

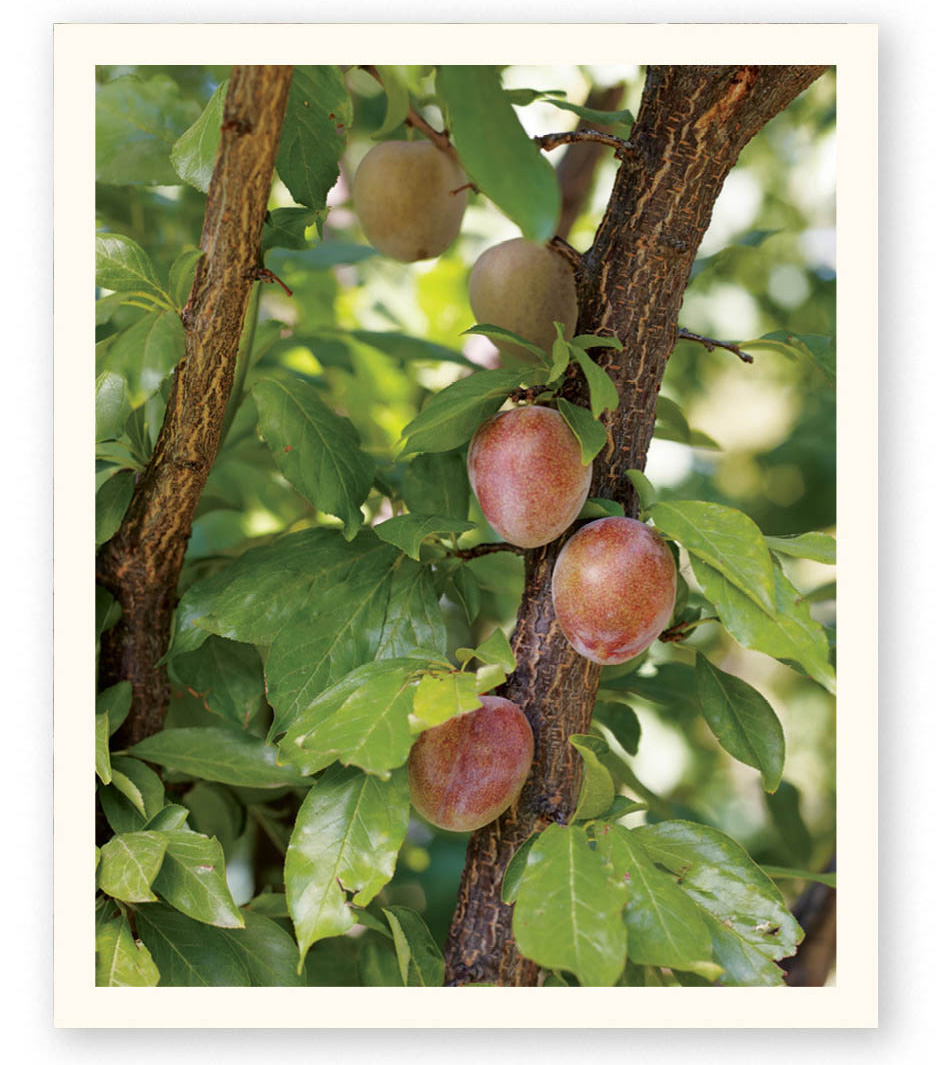

Classic varieties like Santa Rosa plums have proven themselves to be fruitful, flavorful, and reliable.

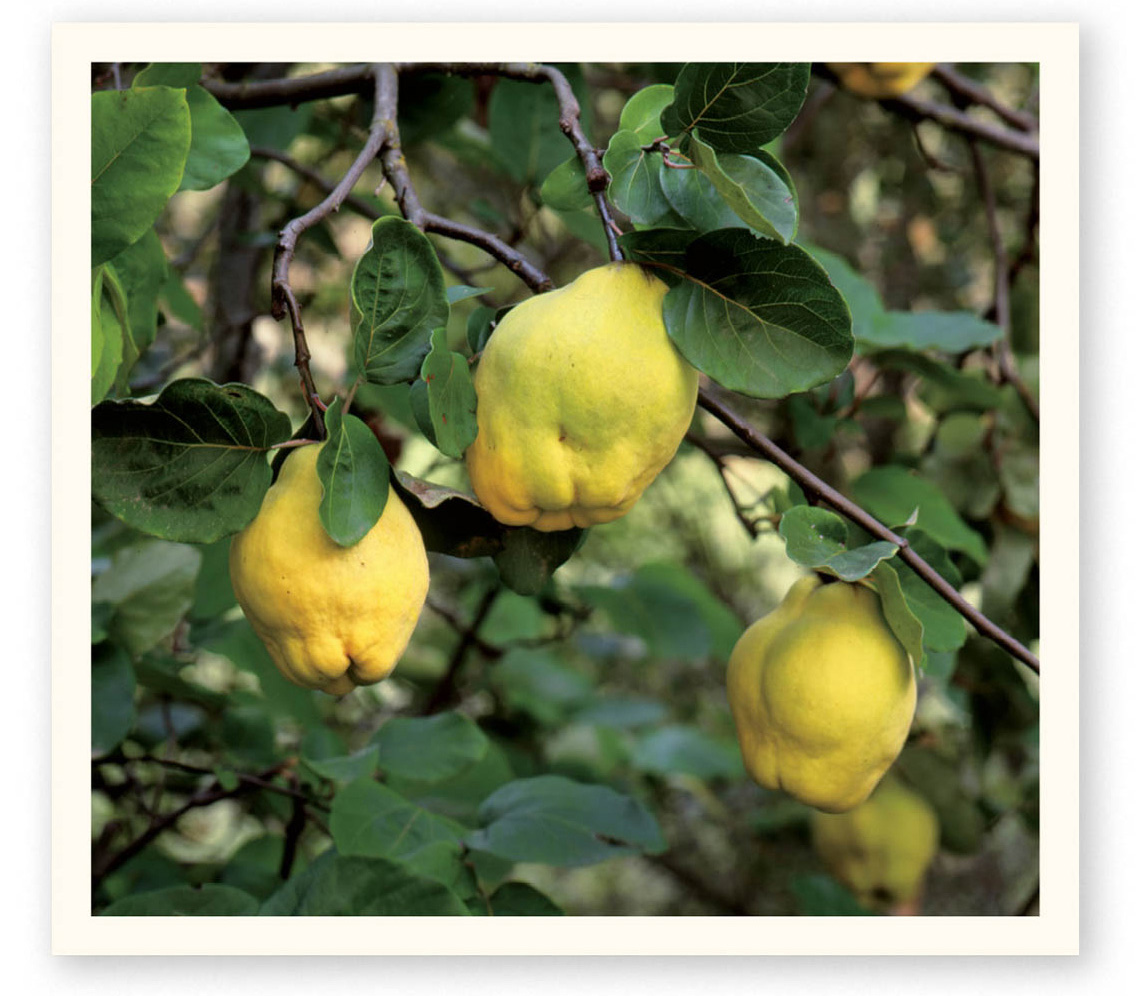

From its parent the rose, the deciduous fruit family tree branches in two directions, pome fruits and stone fruits. The pome branch contains apples, pears, quinces, and also pyracantha, hawthorn, the toyon of Hollywood renown, and, curiously, to me anyway, loquats. The fruit of a pome develops above the former blossom, a position botanically classified as “inferior,” and around one of its principle characteristics, a seed-containing core. The nubbin you see at the end of an apple is the former flower.

A stone fruit is the common name for a type of drupe, a fruit that develops around a hard pit. Stone fruits are termed “superior” because fruit develops from the center of the blossom. The stone branch of the family tree, named for its stone, or pit, includes peaches, plums, cherries, and almonds. Almonds are actually stone fruits that lack the fleshy part of the fruit that we would normally consume if we were eating a plum or a cherry. With almonds, we eat the seed that grows inside the hard pit.

This information has botanical sorting significance, but do these distinctions matter to the ordinary fruit grower? Not very much. Pruning is not that different between the two, or it doesn’t have to be. Most stone fruits grow more quickly and have shorter life spans than pome fruits. Pome fruit trees tend to be stronger and therefore better adapted to espalier. Still, these terms are used as identifiers. It’s useful to know the terminology.

The fruit of a pome, like this quince, develops around its principal characteristic, a seed-containing core. Apples and pears are also pome fruits.

When considering variety selection, think about climate. Match your use and flavor requirements to fruit that excels where you live. The Cooperative Extension Service maintains fruit variety recommendations county by county and other information that gives you your best chance for success in any region of the country. The more your county depends on agriculture, the more critical Extension Service information is to farmers, and the more likely it will be an active and vital part of the local agricultural community.

All kinds of factors dictate whether fruit trees perform well or poorly: heat, cold, frost, soil quality, and the length of the growing season. Some trees won’t produce fruit under adverse conditions or produce fruit so occasionally it isn’t worth the trouble. Some trees languish, and some trees die outright. Legendary fruit might not live up to its reputation in your climate. The insipid flavor of peaches grown where summers are cool will break your heart. A prudent fruit grower accepts the realities of climate limitation.

Varieties also have differing requirements for winter chill. In the roughest possible terms, the higher the number of chill hours, the longer the temperature has to be cold for the tree to do well. Cold weather forces deciduous trees into dormancy. High-chill trees want to grow in Vermont. Low-chill regions like Florida and Los Angeles confuse a tree about its dormancy. This can result in long and erratic bloom cycles that ultimately shorten the life of the tree. Fruit set can be spotty. For the most reliable results, match your tree to your region and climate zone. A good local nursery should have solid, climate-specific information and a history of customer experience regarding varieties that do well locally. Cooperative Extension agents can help with advice about chill.

In general, you’re wise to stay within the winter chill range of your region, but there are no hard and fast rules here. Chill science is inexact, and pockets of climate diversity, called microclimates, allow trees to grow outside their chill range. A favorite fruit that is borderline might be a candidate for an experiment. Depending on the specifics of each location, unusual or otherwise chancy varieties might be worth a try. Experiments won’t necessarily fail. Maybe a tree that produces a few samples of your dream fruit every fifth year will be good enough. Sometimes, trees planted by people who didn’t know better do surprisingly well.

Summer heat may be more important than winter chill. As a rule, summer heat increases the sugar content of fruit, but some fruits require heat and some prefer it cooler. Find out what works in your climate zone. Check with your neighbors. If your neighbors grow apricots successfully, you probably can, too. Be leery of seductive photographs and descriptions found in catalogs, and get the straight story from a responsible purveyor of fruit trees. Most independent nurseries make every effort to be sure their variety selections are appropriate to locale.

Bees transfer pollen blossom to blossom — no bees, no fruit.

The male part of a blossom, the stamen, must transfer pollen to the female part of the flower, the pistil, to make fruit. Most fruit trees available for sale use their own pollen for this job. These trees are called self-fruitful. Some trees require pollen from a pollenizer, a different variety of the same tree — a Grimes Golden apple to complement a Gravenstein, for example — to produce fruit, a process called cross-pollination. Peaches that need a pollenizer need a different variety of peach. Plums need a different variety of plum. Pluots being mostly plum, need a plum or pluot pollenizer. Apriums being mostly apricot need an apricot pollenizer. Your local nursery or Extension agent should be able to provide information about whether pollenizers are necessary and, if so, which varieties are your best options.

You can borrow the pollenizing capacity of neighborhood fruit trees or even place a container full of appropriate blossoms beneath a flowering tree.

Most people prefer to buy one tree instead of two or more, and fruit sellers comply. Most fruit trees available for sale are self-fruitful, and many are partly self-fruitful, meaning that, with help from bees, a solitary tree can produce fruit on its own. Apples, pears, plums, and pie cherries set more fruit with cross-pollination, even if they are described as self-fruitful, but if your preferred tree is self-fruitful, buy it, plant it, and don’t give pollination another thought.

Some excellent exceptions like the Flavor Queen pluot, the Mariposa plum, the Emerald Beaut plum, the aforementioned Yellow Bellflower apple — all worth growing — require a pollenizer to produce fruit. If your favorite fruit tree needs a pollenizer, it should say so on the tree tag. Some trees need specific varieties for pollination, choices that are associated with bloom time. Check to be sure.

People who avoid trees that need pollenizers miss out on terrific fruit. The corresponding tree should be situated nearby. Bees pollinate flowers and fly long distances in warm, sunny weather but won’t venture far when it’s chilly and overcast. The closer together you put your trees, the more reliable the pollination, whatever the weather. Close planting neatly resolves issues of pollination. You can also borrow the pollenizing capacity of neighborhood fruit trees or even place a container full of appropriate blossoms beneath a flowering tree.

At a pruning workshop in Sabi Inderkum and Laureen Asato’s backyard in Richmond, California, someone raised the topic of apricots in the East Bay.

“A lot depends on microclimate, but apricot growing is dicey,” I said. I told the class they might harvest a real crop every fifth year or so. It often rains while the trees are in flower, so pollination is spotty. Apricot roots are sensitive to the heavy, waterlogged soils common here. East Bay weather encourages brown rot. A relentless cloud cover makes almost every year a bad year for apricots.

I asked Sabi and Laureen how crops had been on their six-year-old Blenheim apricot tree.

Consistently poor, they acknowledged. Only ever a handful.

Laureen’s face brightened, and she smiled.

They were wonderful, she said.

One key to successful gardening has less to do with soil, sunlight, and plants, and much to do with attitude and expectations. If your results match your expectations, you’ve got it made. Naturally, there’s a lot of variability in both what people expect and what plants can do. The closer your ambitions align with what’s possible, the more likely your success. Laureen might want to harvest two hundred apricots, and will, one of these years when the weather cooperates. If her goal is “wonderful apricots,” however, she succeeded.

When you garden, good results depend on three things: what you expect the plant to do, what the plant is capable of in the environment where you put it, and your willingness to contribute. Fruit growing, while not difficult, improves with participation. One sure way to disenchantment with fruit growing specifically or gardening generally is to relinquish attentive participation.

It’s worthwhile to look at expectations and environment in greater detail.

Maybe you have a low-bar objective. You have a space where you want to plant something that doesn’t require much attention. This limits your choices but such plants exist. Perhaps your ambitions are greater and you want flowers or fruit. Some of us aim to be the envy of the neighborhood. Fine intentions, all. It’s useful to know what you want and what you’re willing to do to get it.

Say you want a fruit tree. Reasonable enough. Except that fruit trees make demands on your time and attention. In much of California, growing a Meyer lemon is like keeping a goldfish. Attending to a full-sized apricot is more like looking after a goat. Maybe you want the goat, but you don’t want to tend it, so you hire a caretaker. That works fine. Or you decide that a goat is too much trouble. You plant the Meyer lemon. That story has a happy ending, too.

When you garden, good results depend on three things: what you expect the plant to do, what the plant is capable of in the environment where you put it, and your willingness to contribute.

When you want a more companionable relationship and willingly accept responsibility, though, the best arrangement takes the form of a compact. You pay attention and learn what you can. You check in from time to time and care for the needs of your fruit tree yourself — prune when necessary, thin the fruit, watch the water, and monitor pests and disease. With this kind of attention, a connection grows. The tree teaches you about itself. You become acquainted with its seasonal routines. You learn its language, and as you invest more time and your knowledge and skills increase, the bond between you, the tree, and the bigger picture becomes more satisfying. Fruit is only one reward of growing a fruit tree.

This final item about a plant’s environment should be obvious, but when I started gardening, it wasn’t obvious to me. Plants don’t necessarily thrive where you want to put them. As a novice, I planted plants according to my preference and with utter disregard for theirs. I installed moisture-loving coastal plants in my arid San Joaquin Valley garden, bearded iris in the shade, and rain-dependent prairie rudbeckia next to salvia in a dry perennial bed.

The characteristics in the different plants we see around us are adaptive. Plants with certain traits survive in response to the demands of their native setting. These variations play out in the backyard. When you observe naturally occurring differences to heat, cold, sun, shade, water, and drought, you stop battling Nature and join with it in a way that works better for you, the plants involved, and even the wider environment. The elegance of these adaptations merits attention, too. Differences are interesting. The feast is everywhere, from a Central Valley vernal pool to the deciduous forests of Vermont. Align a plant to its environment, and you’re halfway home.

Home gardeners have an opportunity to play a role in the protection and revival of heirloom varieties, and the preservation of botanical diversity. The demands of commerce sometimes eliminate old fruit varieties for reasons that have little to do with flavor, quality, or their value to backyard growers. An heirloom that produces superbly flavored fruit might be poorly shippable, not fruit prolifically, or — like the otherwise notable Northern Spy apple — might be slow to bear. Quality fruit might be smaller or less attractive than shoppers have come to expect.

Trees of Antiquity is a mail-order fruit tree company in Paso Robles, California, with a specialty in heirlooms. Owner Neil Collins recommends a few varieties ideally suited to the backyard garden, and we’ll get to those shortly. Primary considerations that dictate fruit choice, he says, depend on whether a variety is regionally appropriate, disease resistant, and attractive in the garden. Weather patterns, cold, heat, and in between, always determine how well fruit will do. Disease susceptibility varies greatly from one climate to the next and one variety to the next. Cold hardiness and late bloom are especially important in cold climates. Humidity aggravates disease problems. Even so, there are rare, old, and unusual varieties that suit the mildest climate to the most extreme.

Neil also proposes that we too often undervalue the landscape applications of fruit trees. Moorpark apricots grow to be beautiful trees that produce highly flavored fruit. Seckel pear trees reveal an exquisite limb structure in winter, and the pears are small, pretty, and delicious from the tree without storage. He’s enthusiastic about “the gages” for backyard planting. Not to be confused with the Asian greengage, these old European gage plums are sweet, versatile, handsome, and sturdy. Figs create a lush, tropical effect and are easy to grow. Try pomegranates and jujubes if you have drought and heat and are looking for ornamental fruiters. Fruiting quinces have exquisite flowers and a handsome growth habit. To everyone’s regret, cherry trees are finicky, fussy about drainage, disease-prone, and need some winter cold to fruit well but are also sensitive to cold and heat. They are gorgeous and delicious, though, if you can get them to work. Neil admires the Grimes Golden apple, a possible parent of Golden Delicious, which offers the benefits of its offspring and a more complex flavor.

Nowhere is the superiority of homegrown fruit more evident than in tree-ripe peaches, Neil says. To start, he recommends Red Havens. They keep you in peaches for a six-week-long harvest period, bloom late, and take the cold. George IV is “one of the three best white-fleshed peaches of all time,” with melting, juicy, aromatic, and richly flavored flesh. The Peregrine peach is almost fuzzless and produces excellent flavor even in mild climates.

Prepare yourself for peach leaf curl in sensitive regions, a fungal disease that causes leaves of peaches and nectarines to thicken and curl like cooked bacon. Incidents of leaf curl will be now better, now worse depending on weather patterns. The copper fungicides effective against leaf curl are no longer available. Ed Laivo relates that a tent of row cover over small and espaliered peach (and nectarine) trees as the leaves emerge in the rainy season can be surprisingly helpful with leaf curl, and an especially good reason to keep these types of trees small. Peach leaf curl alarms peach growers perhaps more than it should. Adjusting our standards may be the best defense. Remove infected foliage, and treat the tree to some organic fertilizer. Once the curled leaves fall, the tree will grow a new set of uninfected foliage.