Kiel, January 5, 1944

THE OPERATIONS PLANNED by Pinetree for January 5th again had Kiel as their prime objective. A total of 247 bombers in three B-17 wings from the First Division, followed by three B-24 wings from the Second, were to hit the U-boat shipbuilding center accompanied by six PFF ships in case blind bombing was required. They would again be escorted by the Eighth’s two P-38 groups and the single group of P-51s available.

Meanwhile, the Eighth’s P47s, helped by RAF Spitfires and Typhoons, were to escort 274 heavies in attacks against other targets in France and Germany: an antishipping bomber base and repair depot at Bordeaux-Merignac, the “important advanced bomber training base” at Tours, and a ball bearing plant at Elberfeld, Germany.

The 303rd fit into the plan at two points. The 358th Squadron was to contribute six ships as high squadron of the lead group in the second wing going to Kiel. This force would be led by the 379th Group, which was supplying 20 ships to fill the two other squadron positions in the formation. The main 303rd effort was a group of 19 ships forming the low group of the next wing. The 359th Squadron was Group lead under Major Richard Cole and Lt. J.P. Manning’s crew, with Mac McCormick as Group Bombardier. The 360th Squadron was high and the 427th was low.

Hullar’s crew was leading the 427th in Pougue Ma Hone, B-17G 42-31060. The ship, whose name means “Kiss My Ass” in Gaelic, may have belonged to Lt. F.X. Sullivan, a new pilot who was filling the copilot seat next to Bob Hullar. All of Hullar’s enlisted regulars were aboard, including Marson, who wanted to make up one of the missions he missed while Klint’s crew was sitting this one out. Occupying the nose with Elmer Brown was Lt. M.L. Cornish, an experienced bombardier.

Getting the Group off the ground and properly assembled would be touchy. At the 0415 briefing, the crews were told they would be taking off into darkness. The first bomber was to roll down the runway at 0715, and from there, Hoyt recalls, “the tail gunners were briefed to flash their hand-held Aldis lamps for the plane behind to see.” Pougue Ma Hone was the 14th Fortress to go, getting off at 0740, and things started to go radically wrong almost as soon as she was airborne.

Elmer Brown wrote: “We took off and circled the field about once when a B-17 went whizzing by us under our left wing going in the opposite direction. Then the left waist gunner called a plane at eight o’clock level. We were all very much on the alert for other aircraft. I looked out at about eight-thirty and bang—there was the biggest ball of flame I have ever seen and the concussion of the explosion tossed our plane around like a cork on water.”

To George Hoyt, it seemed that “no sooner had Pete Fullem uttered his warning on the intercom than a huge and awesome white, yellow, and orange fireball exploded outside my left window. It lit up the whole quadrant of sky around eight-thirty and revealed the terrain all around just several hundred feet below us. Out of the fireball I saw debris arching skyward, including a human body with arms and legs thrown out as it hurtled upward. It was utterly grotesque.

“I heard Hullar yell, ‘Let’s get the hell out of here!’ as the concussion slapped our plane upwards as though it were a leaf in a storm. Then our plane began to drop like a brick. I thought we were fatally damaged and I grabbed the radio table to brace myself for the crash as we neared the ground. But Bob Hullar saved us. He revved up the engines and we began gaining altitude again.”

Merlin Miller remembers “Pete letting out a yell about a plane whizzing by us in the dark going the wrong way, which of course attracted our attention considerably. We started looking, and it seemed like just a few seconds after that the explosion occurred. It was pretty much under us, off to one side, and it was quite a shock. The plane started to rise, and it felt to me almost like we were riding a ball of fire straight up, just like we were in an elevator or something. It was a big black ball with red tongues of flame sticking out that seemed to be right under us, and it stayed with us as we went up. We didn’t know what caused it, but it sure scared the hell out of us.”

Norman Sampson was in the ball turret at the time, and remembers “The explosion and ball of fire were just terrible. I didn’t know what it was. I thought maybe the Germans were bombing our field.”

Almost the same thought occurred to Major Ed Snyder. “I was in the control tower on the field. There was a hell of a big boom, and then I saw a big fireball and burning debris in the sky for a moment or two. When I saw that I thought, ‘Jesus, do we have an enemy fighter in the air?’ I thought maybe a night fighter had shot one of our planes down. But it just wasn’t right for that.

“We got on the horn to Kimbolton tower right away and within seconds the collaboration between us made it apparent that one of their ships had run into one of ours. There was very little separation between the two bases and somebody obviously had strayed, cutting a corner or something in the pattern. It was tough, but the mission had to go on.”

The unlucky aircraft were No. 747 from the 379th Group and B-17G 42-31441 of the 360th Squadron, flown by Lt. B.J. Burkitt’s crew. They had taken off as No. 5 ship of the high squadron, just three ahead of Pougue Ma Hone.

There was still more tragedy as the 379th and 303rd tried to complete assembly in the dark.

“There were four big fires on the ground,” Brown wrote, “and we learned after we returned from the mission that apparently two other planes just got screwed up on their instruments and flew their ships into the ground. I believe a waist gunner is the only one that lived in the four planes and he had some broken ribs. The bombs in these ships continued to explode throughout the day. They say at noon there was a big explosion.”

The 303rd never recovered from this terrible beginning. The 358th Squadron failed to make its contact with the main 379th formation and returned to base early.

Of the main 303rd formation, Brown wrote: “The Group assembled and left the base as scheduled,” but the balance of his entry makes one wonder if the effort was worth it:

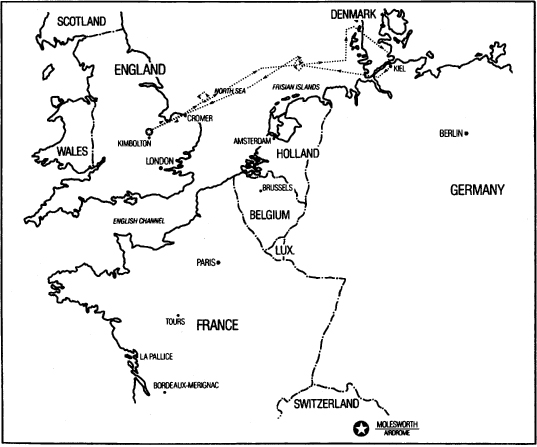

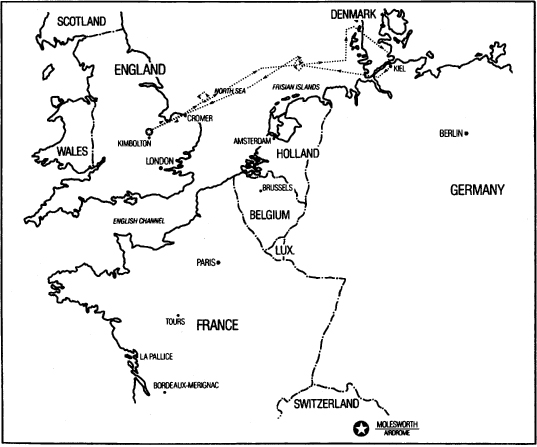

“We had a layer of stratus clouds about 10,000 feet out over about 100 miles of the North Sea so we could not start our climb when we left the English coast (Cromer). Soon after leaving the coast we started running collision courses with other wings of B-17s and B-24s. We were a little late and never did get in our correct slot. We circled to avoid these other formations and ended up trailing the whole Eighth Air Force.

“There we were, leading the low squadron of the low group, the tail end of the whole show. We only had four planes in our squadron and the same was true of the other two squadrons in our group—a group of 12 airplanes. Pretty sad. After we made the circle, our squadron was lagging and Hullar never did catch the group, although we were indicating 170 most of the time.”

Everybody aboard Pougue Ma Hone was agitated about the state of things at this point. Merlin Miller recalls, “We had trouble with one of our superchargers and we had a lot of difficulty. We couldn’t hook up with our group and we seemed to hook in with somebody and then somebody else and it all got to be rather confusing.”

303rd Bomb Group Mission Route(s): Kiel, January 5, 1944. (Map courtesy Waters Design Associates, Inc.)

George Hoyt remembers: “Out over the coast of England and the North Sea we circled so much that several times we were flying with the sun at six o’clock heading back towards England. Each time I figured that the mission was scrubbed and that we were going home.”

It was not to be. As Miller recounts, “We decided to go on with the mission anyway,” and Norman Sampson remembers having “a very hollow feeling about completing this one.”

Elmer Brown’s diary picks up the narrative:

“About halfway cross the North Sea, clouds started breaking up and we started a gradual climb. The climb was too slow as we reached sight of the German coast about 20 miles south of course at about 18,000 feet and we were supposed to be at bombing altitude of 25,000 feet. We went north along the coast trying to gain altitude and get on the intended course.

“I had Hullar cutting corners, trying to catch the group because we were supposed to drop our bombs on the group leader. I did pilotage up to within a few miles of the IP, then we started getting attacks from enemy fighters and there we were, still about a mile and a half behind.”

The crew now faced a running battle with fighters while trying to set up on the bomb run. At interrogation the men reported encounters with 12 to 15 Ju-88s, Me-109s, 110s, and 210s.

Elmer Brown wrote: “I got busy watching and shooting at enemy fighters and trying to figure out how to catch the group. I was depending on DR for navigation, but it didn’t work out as we had a strong, unexpected tailwind and reached the target much sooner than we were supposed to. Our group released the bombs but we were so far behind we could not see them go and we didn’t think they bombed.”

The main Group had bombed “with results reported as fair to good” and then, Brown recorded, “they made a gradual turn to the west and we made a sharp turn to catch up with them. In doing so we cut across a corner of Kiel, the target, but I was so busy I didn’t realize it. I figured they were going to circle around and take another run. When we realized they were going home, we dropped our bombs in the sea hoping that we might hit one of the ships down there.”

These were “12 naval vessels…on a heading of about 280 degrees true” which Hullar’s crew had spied, but Brown wrote: “no luck.”

Another reason for Brown’s preoccupation over Kiel was the flak. It was “moderate” but “fairly accurate” from the IP into the city and the crew reported that “we had to take pretty violent evasive action.”

Miller remembers “The young lieutenant who was flying with us said later he thought he knew what evasive action was until Hullar started bouncing us around. Then he learned what it was really like.”

All the while, George Hoyt recalls, “German fighters were around, and they were not at all bashful about making attacks. B-24s were flying on both sides of us, and they drew off a lot of the fighters. We considered them our best ‘fighter escort.’”

Brown “saw several planes, B-17s, B-24s, and enemy go down in flames,” and he was drawn to the B-24s, which “were flying very erratic. Those guys would abort just before the bomb run.”

One B-24 made a vivid impression on him: “A vertical fin and rudder came off a B-24 and sailed through the air like a paper plate, but the B-24 went flying along with one rudder like nothing happened.”

Merlin Miller remembers that “We did get a fair number of attacks coming out. There were a good number of German fighters that jumped us the first time, and then some of them went after the B-24s. It did seem to me that they had some kind of problem with their formations. But we were still getting fighter attacks, and Hullar was still taking violent evasive action. Some P-51s finally took the German fighters off of us about the time that things started to get real serious.”

At 1158 Hullar’s crew reported that a “P-51 got a T/E E/A” that “was smoking on the way down,” and during the fight other Group members saw the Mustangs at work.

Sgt. Edward Carter, top turret gunner of Baltimore Bounce in the No. 3 slot of the lead squadron, later said: “Two Ju-88s dove down on us and then two P-51s dove on them. In a few seconds all that was left in the air was the two P-51s and just scattered bits of the two Ju-88s.”

What the men were witnessing was a P-51 field day. By the time they were through, VIII Bomber Command reported that the Mustangs had decimated “a large group of rocket firing Me-110s approaching our bombers” and had “destroyed 16 E/A in all in the target area, with no casualties to themselves.”

The overwater flight back was uneventful, but Hoyt remembers that “shortly inside the coast the bombardier reported two B-17s wrecked on a hillside. The cards were stacked against us today.”

Elmer Brown wrote: “We had about a 500-foot ceiling and less than a mile visibility for landing at the base, but it wasn’t as bad as I have seen in fog when we were coming in for a landing.” Pougue Ma Hone touched down at 1510, after exactly seven and a half hours in the air.

There was much anger among the 41st CBW’s bomber crews at debriefing. As Elmer Brown recalls, “I was furious about them having sent us up in the dark that way, so that those midair collisions could happen. This was one the high command really screwed up.”

Many other crews showed their displeasure at both Molesworth and Kimbolton, where the 379th was also licking its wounds after a flight over the Continent just as chaotic as the 303rd’s.

Two pilots of the 379th summed up the lesson best. Lt. Kenneth Davis commented: “No more night takeoff. Four fires seen in vicinity of field. Just missed collisions. Nothing gained—never got into formation till daylight anyway.”

Lt. Edward R. Watson, Jr. said, “Dispense with night assembly—too dangerous.”

The Eighth’s planners took the comments to heart. As Ed Snyder recollects, “After this one there weren’t any other predawn assemblies I can recall during the time I was there.”

The Eighth’s operations concluded with mixed results. Strike photos over Kiel showed “extensive damage at various localities” in the city, but a total of 10 bombers were lost. The three Third Division wings bombed the Bordeaux-Merignac Airdrome with good results, but strong enemy fighter attacks were made on them after two P-47 groups providing penetration escort left in the vicinity of La Pallice. Seven B-17s fell. The two First Division wings dropped on Tours at a cost of one Fortress, and the last two wings of the Third Division missed the Elberfeld ball bearing plant altogether because of PFF equipment failure and bad visibility. They lost one B-17.

With the collisions and crashes during morning assembly, the total number of bombers lost was 25, with 12 missing fighters. The price was high, but it would pale in comparison with the casualties from a raid soon to be set in motion by an entirely new command team at Eighth Air Force Headquarters.