Old Soldiers Who Don’t Fade Away

WITH THE END of hostilities in Europe on May 7, 1945, the 303rd was soon prepared for other missions. The very next day, in the midst of VE Day celebrations, Bob Hullar was appointed Group Operations Officer, replacing Major Mel Schulstad, and for a while it appeared that the Group would be deployed to the Pacific to take part in the final strategic bombing campaign against Japan. However, this proved unnecessary, and while the Group’s bombers flew “Continental Express” missions over Europe that month to show the ground echelon some of the results of its bombing missions against Germany, others in the Group, including Bob Hullar, prepared for a redeployment of the 303rd to the North African Division of the Air Transport Command in Casablanca. The transfer of personnel began on May 30, 1945; its purpose was to have the Group take part in “Green Project” ferry missions transporting ETO veterans back to the United States. Here too, however, the powers that be later determined that the 303rd would not be needed, and the Group soon found itself without a mission. Bob Hullar was present when the Hell’s Angels 303rd Bombardment Group (H) was formally deactivated in Casablanca on July 25, 1945.

During the Cold War the Hell’s Angels were reactivated as the 303rd Bombardment Wing, Medium, based at Davis Montham Air Force Base, Arizona from 1951 through 1964. The 303rd flew Boeing B-29 bombers and KB-29 aerial refueling tankers from 1951 through 1953, and later transitioned to Boeing B-47 jet bombers and Boeing KC-97 aerial refueling tankers. The Group was deactivated again until, in 1986, the 303rd found a new military incarnation in the 303rd Tactical Missile Wing which was based in Molesworth just like the original Hell’s Angels. The new 303rd was responsible for maintenance and readiness of the controversial Ground Launched Cruise Missiles which were deployed to Europe at the end of the Cold War, and Molesworth became the scene of many, well publicized antimilitary protests. The new 303rd soldiered on, however, until the Cold War was won in 1989 when the 303rd was deactivated again.

Today, there is no 303rd in the U.S. Air Force’s table of organization, but the military men and women of the Joint Analysis Center, which has been stationed at Molesworth since 1991, are very much aware that the Base they occupy is hallowed ground. The JAC has named its new operations center the “Might in Flight” building, after the 303rd’s motto, and the exterior and interior of the building are replete with reminders of what took place there between 1942 and 1945. The old, large main hanger which dates from the war has a large “Triangle C” B-17 tail insignia on its doors. A standing invitation has been issued to every 303rd veteran to visit the facility, and it is very obvious to anyone touring Molesworth today that the JAC is true to one of its own mottoes, “Molesworth Remembers.”

The men of the 303rd Association will always remember the comrades-in-arms they served with, and a moving part of each reunion is the reading of a list of those who have passed away since the last gathering. The deceased on Hullar’s crew now include Hullar himself, Elmer Brown, Dale Rice, Pete Fullem, and Chuck Marson.

Col. Robert J. Hullar while serving as Base Commander at Pleiku Air Force Base, Vietnam, 1966-67. (Photo Courtesy Mrs. Jean J. Hullar.)

Bob Hullar stayed in the Air Force after the war, married in 1946, and had three children. Many of his assignments were in staff and quasi-diplomatic posts, and he was also the base commander of a number of Air Force facilities. These included England Air Force Base in Alexandria, Louisiana in 1962,* and Pleiku Air Force Base, Vietnam for 14 months in 1966-77. He retired from the Air Force in 1970, earned a master’s degree, and was active in private business until his death of bone cancer in October of 1984. Although the writer never met him, everything I have learned about Bob Hullar from others convinces me that he perfectly embodied the military ideal of “an officer and a gentlemen” until the end of his life.

Although he was tempted to stay in the military, Elmer Brown returned to civilian life and realized his dream of starting a family with Peggyann. They had two children, Larry and Bonnie, in the late 1940s. Elmer returned to the design and construction field that he had worked in as a drafter before the war, earning a BS degree in civil engineering in 1954. He spent his career as a government employee, and was involved in many military construction projects in the Pacific. In 1964 he was working as a government project engineer at a McDonnell Douglas facility in Huntington Beach, California, a position he occupied until his retirement in 1973. He remained in Southern California with Peggyann, where for the last two decades of his life he fought a long and ultimately losing battle against Parkinson’s disease, finally succumbing on August 3, 1997. He was very active and involved in the writer’s work on the original edition of this book, since he had always wanted a book written about his Eighth Air Force experiences. I take great satisfaction in learning from his son Larry that Elmer’s interest in this work did much to sustain him in his last years.

Dale Rice also returned to civilian life after the war, marrying, raising a family, and ultimately settling in Rahway, New Jersey. He made up for the lack of educational opportunity that he felt so keenly before entering the service by obtaining a high school equivalency certificate while working for a Rahway-based pharmaceutical company, and then attending night school at Rutgers University from 1956 to 1963, where he earned a B.S. in Business Administration. Not content with this, Rice then became an educator himself, starting a long career at Rahway Junior High School, during which time he continued to study at night, earning a Master’s Degree in Behavioral Science and accumulating many additional credits in a Master’s Plus Program. He loved children and teaching and was, I am told, greatly beloved by his family and students. He died shortly before I first began research for this book in 1985.

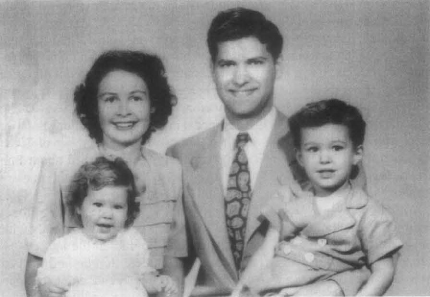

“The Best Years of Our Lives.” Elmer Brown realized his dream of starting a family with Peggyann, and he went on to a successful postwar career as a civil engineer, working all over the world with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. This photo shows the Browns with their two children, Larry and Bonnie, circa 1948. (Photo courtesy Elmer L. Brown, Jr.)

Pete Fullem likewise returned to New Jersey after the war, where he periodically got together with Dale Rice. He received training as a watchmaker in 1946, opened his own jewelry store in Jersey City, and died in 1980. Little of his postwar life is known beyond the bare documentary record, which includes some personal photographs and newspaper clippings given to me by one of his relatives when I first began research into Hullar’s crew. What I did learn about him convinced me that here was an unassuming man whose deeds should be remembered, which is why I have tried to give his role in Hullar’s crew the prominence that it has in this book.

Chuck Marson moved from the backwoods of Maine to settle in Roswell, New Mexico after the war, and he was active in the New Mexico National Guard until he could no longer pass the physical. His widow Sarah has said that he was “one of a kind, a real character. He was tough as nails on the outside and soft as butter on the inside. Kids, especially teenagers, adored him.” He died of a heart attack in 1980, during the thirty-fifth year of their marriage.

Norman Sampson lives a quiet but happy retirement in the small town of Ozark, Missouri with Anita, his wife of over fifty years. A deeply religious man, he is quick to say, “I never felt I was any kind of hero,” but those knowing the missions he flew can easily draw a very different conclusion.

“Mac” McCormick, Hullar’s ace bombardier, shuns the limelight even more. A retired chiropractic physician, he now lives in a small town in Idaho.

What is known of some of the other men who flew with Hullar’s crew, some now deceased and others very much alive, follows:

Flamboyant “Woodie” Woddrop was killed in an aircraft accident involving a B-29 while he was in transition training for deployment to the Pacific. The B-29’s Wright R-3350 engines were plagued with cooling problems when first mated to the aircraft, and there were frequent engine fires. Woddrop’s B-29 experienced one during a takeoff and in exiting the aircraft through the nosewheel door “Woodie” somehow managed to run into the spinning propeller on one of the inboard engines. He suffered massive injuries and his friend, David Shelhamer, learned later that Woddrop died on the operating table of the base hospital.

Crew Reunion. L-R, Merlin Miller, Bud Klint, and Norman Sampson pose for the camera during the 1986 303rd Reunion in Fort Worth, Texas. (Photo Courtesy Wilbur Klint)

After the war Shelhamer moved from his native Chicago to Los Angeles, where he raised a family of four children with his first wife and continued his prewar calling as a professional photographer. Always assertive, nothing stopped him when he met his second wife, Lorraine, about a year after the end of his first marriage, and decided instantly to marry her; the two enjoyed many happy years together. When he developed incurable cancer in the late 1980s David elected to forego “heroic measures” and wait out his time in a hospice. The writer exchanged a number of personal tape recordings with him during this period, and I can say with conviction that David Shelhamer faced death in the end as bravely as on any of the missions he flew.

Grover Henderson, who was Woddrop’s best friend during the war, returned to his home in Greenwood, South Carolina but maintained a lifelong interest in the Air Force and flying. He was a member of the Air Force Reserve, and in 1955 was recalled to flying status in the Ready Reserve, where he served first with the 77th Troop Carrier Squadron at Donaldson Air Force Base in Greenville, South Carolina and then as operations officer of the Search and Rescue division of the 14th Air Force at Headquarters, Robins Air Force Base, Georgia. He was commander of the 9997th Air Force Reserve Squadron in his hometown of Greenwood until he retired with 20 years of active and reserve duty.

Grover also greatly enjoyed civilian flying. He held a commercial pilot’s license and for many years made charter flights for a number of businesses. He also was “on call” as a copilot for a major textile manufacturer. Flying and association with other pilots always gave him pleasure, and he was a most active participant in the 303rd Association as long as his health permitted.

After his death of a heart attack in November 1993, Grover Henderson’s name was added to the Memorial to South Carolina’s Outstanding Pilots in Orangeburg, South Carolina.

Tail gunner Charlie Baggs, whom Grover Henderson always felt was the second “soldier of fortune” on Woddrop’s crew, did not live long after the shooting stopped. Quite by accident George Hoyt ran into Baggs on a street in Atlanta shortly after the war’s end, while Hoyt was attending college. The friendly conversation between the two quickly turned grim when Baggs informed Hoyt that a VA doctor had just told him he didn’t have long to live because of his alcohol problem. Hoyt was depressed for days afterwards by the memory of his old friend slowly walking down the street in the opposite direction after their discussion. In later years Grover Henderson devoted considerable effort to searching for Baggs in his native Colquitt County, to no avail.

Paul Scoggins, the 427th Sqdn. lead navigator who flew a number of missions with Hullar’s crew, returned to the USA in the Spring of 1944 and spent the balance of his service at San Marcos, Texas as a training officer. After the war he earned a B.S. degree in business administration, married, and spent 35 years working for Ralston Purina in a variety of management and sales positions in Texas and Louisiana, followed by five additional years as shop supervisor for a chain of grocery and feed stores. He and his wife, Mary, live in DeRidder, Louisiana, near one of their three daughters. They have 12 grandchildren, and four great grandchildren.

At 77, Scoggins remains active and optimistic about life, as befits a man who has taught Dale Carnegie courses part-time for over thirty years, and who still does so today. Two comments about his combat days nicely sum up both his personal philosophy and his reflections on the war:

“Pop Hamilton, our radio gunner, was always the nervous, chain smoker who worried about everything. He would say, ‘They say a 4% loss on each mission is our average. Lieutenant, 25 times 4% is 100%, so we aren’t coming back.’ My answer was always, ‘Pop, every time we go out, we have a 96% chance of coming back!’”

“I’ve said that we fought a ‘Gentleman’s war’ in the air force. We were in grave danger while we were flying, but we came back to a warm bed (IF we made it, and I did). I was at the right place at the right time. I wouldn’t want to relive the experiences, but I have a good feeling for having been through them.”

Howard “Gene” Hernan, the experienced 359th Squadron top turret gunner on Claude Campbell’s crew, returned to his native Creve Coeur, Illinois after the war, and spent his working life as a loyal “union man.” He died before the first edition of this book was published, but his widow, now also deceased, told me that Gene absolutely hated war, and reserved special anger for the politicians who caused young men to have to fight and the “little people” of this world to suffer in it. To the end of his days, however, Gene was proud of his own wartime service, and he was especially proud to have been a member of Campbell’s crew.

Eddie Deerfield, the 360th Squadron radioman, likewise has enormous pride in having been a part of Robert Cogswell’s crew, so much so that he erected a memorial plaque to his comrades in the gardens outside The Mighty Eighth Air Force Heritage Museum.* Despite an impressive postwar career as a Foreign Service diplomat who served for more than two decades in the U.S. Information Agency; a parallel career as an officer in the U.S. Army Reserve, including active duty in Korea during the Korean War; and the publication of an historical novel, it is easy to conclude that Deerfield’s WWII service as the radioman of Iza Vailable ranks higher on his personal scale of accomplishments.

Two other contributors to this book, members of Don Gamble’s crew, elected to stay in the service after the war. Bill McSween became a navigator instructor, ending his career as a Lt. Col. and retiring with his wife, Bobbie, to a farm near Shreveport, Louisiana. They had three children. Few things motivated me to see this book through to its initial conclusion more than the opening line in a letter McSween sent me—“I was beginning to wonder if you had forgotten me”—when, early in my research, there was a gap in our communications.

Ralph Coburn decided to make the Air Force a career too, despite the close calls he faced on his missions. After returning to the States he also decided there was a part of his Molesworth experience he could not live without. In 1946 his English girlfriend, Beryl, traveled to the U.S. after being demobilized from the WAAFs. They remained married for fifty years, minus two months, and had five children. After his retirement from the Air Force in 1962, Coburn became an educator. He was Dean of Students at Orlando Junior College in Florida, and later a counselor at an adult technical school until his final retirement.

Together with their wives, both McSween and Coburn were frequent attendees at 303rd reunions until both men passed away earlier this decade. McSween died in 1995 and Coburn six months later, in 1996.

Happily, Don Gamble, their outstanding pilot, continues to enjoy good health, and is invariably at the Group’s reunions where he can be seen with Dave Rogan, his old Instructor Pilot, and Charles Schmeltzer, his right waist gunner. Looking back on their collective experience, Don Gamble feels, “We were blessed not to have any of our crew hurt.”

Also to be seen at 303rd reunions is Darrell Gust, who still feels blessed to have survived his last mission, to Oschersleben, that terrible day in January 1944. Long retired, after eight and a half years service in the Air Force, and almost 30 years as the Director of Personnel and Labor Relations for a Wisconsin Power Cooperative, Gust keeps himself busy nowadays as a school bus driver for the children in his Wisconsin community.

On John Henderson’s crew Ed Ruppel passed away in the early 1990s after a long illness. Ruppel’s war experiences had a deep and lasting impact on him, and caused him to refuse interviews with many people whom he felt were only interested in learning, on a superficial level, what he knew about the mission on which Forrest Vosler won the Medal of Honor. From the first of four extraordinarily intense interviews I had with Ruppel, however, it was clear that this man had a much larger story to tell. I will always have a feeling of privilege in the knowledge that he entrusted me to deliver it to a wider audience.

Forrest Vosler died in 1992. After the war he became a member of the original Board of Directors of the Air Force Association, and pursued a long career of service to others as a Veterans Administration counselor. When I interviewed him for the first edition of this book in 1986, 43 years after the fact he still showed the self-confidence and drive which marked him as a man capable of winning the Nation’s highest award for military valor. But there was also an indefinable personal quality, and dignity, about him which in my opinion marked him as a genuine hero as much for who he was as for what he did.

Medal of Honor Winner Forrest Vosler and crewmate Bill Simpkins pose together during the Gala B-17 50th Anniversary Celebration in Seattle in 1985. (Photo Courtesy William H. Simpkins.)

Of John Henderson’s crew only Bill Simpkins is known to survive today, and it is something of a miracle that he is here at all. On February 24, 1944 his B-17 was shot down by flak over Schweinfurt, and while everyone parachuted safely, Simpkins faced many dire threats to his life while in captivity.

Simpkins’ ordeal began on the way to interrogation in Frankfurt. While being shepherded by a single German guard through the main city Bahnhof (railroad station), his group of POWs were pursued by a mob of enraged German civilians who had just lynched some other U.S. airmen. Simpkins saw their bodies hanging from the main overhead girders in the station. He and the other Americans owed their lives to the solitary German soldier, who rushed them to a hiding place underneath the station to escape the mob.

Simpkins was shipped, together with Ed Miller, the crew’s new ball turret gunner, to Stalag 6 on the border of Lithuania in East Prussia. When the Russians began to cut off this part of Germany late in the war, Simpkins and the other Stalag 6 POWs were forced to stand in the hold of a ship during a perilous journey from Königsberg to Stettin, where they arrived in the middle of an Allied air attack. Angry civilians took their belongings and made the POWs run gantlet of bayonets and dogs. The POWs were marched to Stalag 4, but this was only an interim stopping place. When the Russians again threatened, Simpkins and the others were forced, in an atmosphere rife with rumors that orders had gone out to kill all POWs, to make another long and difficult march in the snow. Their journey temporarily ended in Nuremberg, where the forlorn group was strafed by P-47s who killed and wounded some of their number. The POWs were then marched across the Danube River at Weiner Neustadt and put on the road once again until they ended up at Moosberg, Germany where the men were finally liberated by a U.S. Army armored division.

During their long and terrible trek Simpkins and his comrades traded cigarettes for raw meat, and Ed Miller credits Bill Simpkins with saving his life when, one evening, Simpkins literally carried Miller on his back to their resting place for the night. (Those POWs who could not keep up died in the snow.)

After the war Bill Simpkins returned to his native New Jersey where he held a variety of jobs until settling on a career with Lenox China in the early 1950s. He worked as a supervisor of decorating, was active in research and development methodology, and helped establish five factories. He and his wife, Edie, live in the small town of Cologne, New Jersey and are longtime members of the 303rd Association. When, during one of my interviews, I asked how he was able to fly all those missions and then endure the POW experience, he reminded me that he was only 19 years old at the time and said simply, “You had to be young.”

POW experiences like those of Bill Simpkins cry out for a realistic portrayal in writing by someone who was there, and Carl J. Fyler has done just that in his book, Staying Alive. It should be required reading for anyone who harbors “Hogan’s Heroes” type illusions about what being an American POW in the ETO was really like. After the war, Fyler returned to his native Topeka, Kansas where he married, became a Doctor of Dentistry, and practiced his profession until his retirement. A past President of the 303rd Association, he has never stopped being a fierce advocate of veterans’ rights and benefits, and has given selflessly not only to the goal of obtaining a posthumous Medal of Honor for Joseph Sawicki, but to many other deserving cases as well.

The Reverend Charles W. Spencer, the other Kansas veteran who figures large in this book, lived a life characterized by service to others right up to the date of death on April 16, 1998. After graduating from the Baptist Theological Seminary, Kansas City, Kansas, in 1951, he served as Chaplain to the Kansas Soldiers’ Home in Fort Dodge from 1953 to 1982, and continued to assist in Christian ministry at the First Baptist Church in Dodge City as long as his health permitted. According to Jeanne, his wife of 57 years, he always preferred devotion to his ministry to dwelling on his war injuries. If you ask her today what kind of man he was, she will tell you that being with him “was like living a miracle every day. He touched many lives.”

Bill Fort, Spencer’s pilot on the fateful Bremen mission of November 26, 1943, still lives with his wife, Rachael, in a Jacksonville, Florida suburb. Like Charles Spencer, Fort is also a man of few words when it comes to the war. He and Spencer met only once after the November 26 mission and that briefly, and privately, during the 1990 303rd Reunion in Norfolk, Virginia. It is enough to know that their paths crossed again after the war, without trying to delve into what was discussed.

Until his death in 1990, Jack Hendry lived in the same neighborhood as Bill Fort, just a block or two away. Though they flew in the 358th Squadron at the same time, neither knew the other until after the war, when they got acquainted as neighbors and became friends. Jack Hendry married in 1947 and remained in the service until 1950, when he was honorably discharged. He graduated from the University of Florida in 1954 with a Bachelor’s degree in Building Construction. Like Elmer Brown he had two children, and also like Brown he traveled extensively overseas doing construction work for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. However, while working in Europe he refused a grand tour of Berlin at Corps’ expense. His wife, Gloria, believes he did this not because of any lingering animosity towards the Germans, but because “he did not want to see some of the bombing damage still visible there.” A great amateur golfer in retirement, he was clearly an even greater father. When I contacted Mrs. Hendry for information about Jack for this Epilogue, I also received a letter from his son, Michael.

Of Jack Hendry’s brave bomber crew, only Howard Abney remains alive today. John Doherty, who replaced Abney in the War Bride’s tail gunner’s position, died shortly before the publication of the first edition of this book in 1989. Jim Brown, the crew’s radioman and by common consensus one of the crew’s real leaders, is buried in his native Georgia but definitely not forgotten. Brown’s niece, Mrs. Henrietta S. Duke, traveled to Savannah for the most recent 303rd Reunion, where she met Abney to learn more about her uncle.

Ed Snyder, the Hullar crew’s squadron commander, remained in the Air Force after the war, retiring in 1970 as a full Colonel. Like Hullar his career included a number of significant headquarters assignments, in the Far East, Europe, and the Pentagon. The one big surprise to the writer when I interviewed Ed at his home in Tacoma, Washington, was discovering that he was also a combat qualified fighter pilot in F-101s, and that he had logged time in F-106 interceptors as well. Somehow I had expected that he would stick with bombers, but on the other hand…Snyder and his wife, Dot, are frequent attendees at 303rd reunions.

Mel Schulstad, who also lives in the greater Seattle area, is another who stayed in the Air Force after the war. Ironically, in the early 1950s he was assigned to Germany as a staff officer implementing a Military Assistance Plan to rebuild the Luftwaffe and West Germany’s military-industrial infrastructure. He retired as a full Colonel in the 1960s, but his son, Jon M. Schulstad, and his grandson, Jon Jeffrey Schulstad, have both followed in his footsteps as Air Force officers. His son is retired but his grandson is on active duty as a Captain, flying the closest thing to the B-17 in the Air Force inventory—the four-engined, straight-winged, turboprop C-130 “Hercules.”

Today Mel Schulstad is still active in a significant second career. Twenty-six years ago he co-founded the National Association of Alcoholism and Drug Abuse Counselors, a professional organization which now has over 17,000 members. He is presently helping to write a history of the organization.

George Hoyt, Hullar’s radioman, also helped Germany after the war, and he concluded a separate peace with the Germans in a very special way. During the Berlin Airlift Hoyt returned to active duty on a volunteer basis, traveling to Celle, Germany in the British Sector. There he assisted in the establishment of an air traffic control system to guide cargo flights going to and from Berlin in one of the three air corridors to the City. While in Celle he met Elfriede, a young German woman who was a refugee from the East. They were married by the Mayor of Frankfurt am Main while Hoyt was still on active duty.

Upon his return to Georgia Hoyt pursued a successful banking career, and he has a second career as part of the management team at the Stone Mountain Park outside Atlanta. He and Elfriede have two sons and live in the Atlanta suburb of Lilburn.

Merlin Miller, Hullar’s indomitable tail gunner, returned to the United States after his tour was over and spent a number of months in a B-25 training unit. However, he soon tired of this and volunteered for combat in the Pacific. He flew 13 combat missions as the tail gunner with one of the most aggressive, low level B-25 “skip-bombing” and strafing units in the whole Pacific theatre—the “Air Apaches” of the 345th Bomb Group. Hepatitis, not hostile fire, finally knocked Miller out of action, and he returned home to Sullivan County, Indiana, where he married a high school classmate named Marjorie. He and his wife spent many years in the south Chicago suburb of Chicago Heights, where Miller worked as a lumber salesman. Following his retirement they returned to their roots in Sullivan County, where the Millers now reside in the tiny town of Dugger, Indiana. They have one son who works as a corporate attorney in Denver, Colorado.

Merlin wields an oil paintbrush almost as effectively as the twin fifties he used during the war, and he has produced a number of excellent B-17 paintings, though his talents are by no means confined to aviation art. He is also an excellent public speaker, and frequently gives talks about the Eighth Air Force to students. Those wishing to hear him tell what the air war was like in both the ETO and the Pacific should make arrangements to borrow the tape recording of a joint speech—entitled “Eighth Air Force History: Living It and Writing It”—that he and the writer gave on October 18, 1995 before a large audience at The U.S. Air Force Museum, Wright-Paterson Air Force Base near Dayton, Ohio.

The need to create tangible reminders of what was accomplished in the aerial battlefield over Occupied Europe during World War II and what the victory cost in human terms, is one which many Eighth Air Force veterans still work daily to achieve. No one has worked harder at this task than Lewis E. Lyle, the 303rd’s outstanding combat leader. Following his retirement as a Major General in the Air Force, Lyle criss-crossed the country by auto countless times to create interest in and raise financial support for a “people’s museum” to tell the story of the Eighth Air Force in human terms. His efforts have borne fruit in the last two years with the opening and impressive growth of The Mighty Eighth Air Force Heritage Museum, located off Interstate 95 in Pooler, Georgia near Savannah. From its startling “Mission Experience” audio-visual exhibit to its touching exhibits of personal memorabilia, and its sometimes shocking photographs, the Museum succeeds admirably in showing “the way it was.”

It may come as a surprise to some to learn that there are many smaller but no less significant “people’s memorials” located in out-of-the-way fields and odd pieces of real estate all over Europe, from Poland and the Czech Republic to France, the Netherlands, Belgium, Britain, and even Germany. They mark the spots where Allied bombers and fighters crashed, and men were killed. In some cases they are erected by Europeans who have rediscovered the crash sites, and have spared no effort to find out whose life it was that ended amidst the bits of metal, broken Plexiglas, rubber, and even personal effects that may be found with a careful raking of the ground. In others they reflect the wishes of old resistance fighters to mark the spot where they arrived on the scene and helped Allied airmen before the Germans arrived. In all cases they show the strong desire of people now free to honor the memory of those who died helping to make them so.

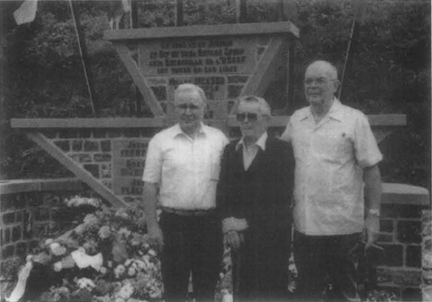

Crew Memorial. Donald Dinwiddie, radioman, (Left) and James F. Fowler pilot (Right) pose on each side of Maurice Lamendin, Belgian Resistance Fighter, before the monument the Belgians dedicated on June 27, 1987 to honor Fowler’s crew near the January 29, 1944 crash site of their B-17, G.I Sheets, in Soire-St-Géry, Belgium. (Photo Courtesy James F. Fowler.)

There are many such memorials honoring 303rd Bomb Group crews, including one erected and dedicated by the townspeople of Soire-St-Géry, Belgium on June 27, 1987 to commemorate the place where Lt. James Fowler’s G.I. Sheets crashed on January 29, 1944 and Sgt. Miller O. Jackson died. Surviving members of the crew and their families attended, including Jim Fowler and his copilot, Barney Rawlings. After a lifelong career as an airline pilot after the war, Rawlings was moved to write his own book about their crew, entitled Off We Went (Into the Wild Blue Yonder).

Bud Klint has been active in placing a number of memorials in memory of the 303rd at various locations in the United States, but these activities occurred long after his return to civilian life. Back in America after the war he met and married his wife, Mary, resumed his job at the candy company in 1946, and followed its fortunes through a number of corporate mergers and position changes until he moved to Fort Worth, Texas, where he was Director of Marketing and Sales for the King Candy Company. Klint left the candy business in 1972 in order to join Tandy Corporation, where he worked in the advertising department as Director of Newspaper Media until his retirement in 1981.

All during these years, Bud Klint’s priorities were the same as those of the other veterans and fathers of his generation—earn an income, raise his children (the Klints have three and now have eight grandchildren), get ahead in his career—but in all this time Klint’s World War II experiences were “always there, in the background.” So when Bud Klint “finally started to live” after his retirement, his interests returned to that period in his life when he wondered if he would live at all. He became an active member of the 303rd Association, of which he is a past president;* of The Eighth Air Force Historical Society; and last but not least, of a special veterans group whose membership is necessarily limited: The Second Schweinfurt Memorial Association, or SSMA.

Bud Klint’s efforts to ensure that those who died in the war are remembered found its ultimate expression in June of 1998, when he headed up a small contingent of SSMA veterans and family members on his last mission to Schweinfurt. They were there at the invitation of Georg Schäfer, who heads up a German veterans’ organization of the Luftwaffenhelfer who manned the City’s flak guns against the Americans throughout the war. There, the two groups of former enemies jointly dedicated an extraordinary memorial, crafted by one of the Luftwaffenhelfer, to remember the fallen on both sides during the many bombing raids against the City, and on “Black Thursday” in particular.

Old enemies united in friendship. Bud Klint, (Left) and George Schäfer pose before the German-American Memorial in Schweinfurt during dedication ceremonies on June 16, 1998. The monument was created by G. Hubert Neidhard, one of the Luftwaffenhefler who manned the flak guns against the American bombers. The inscription reads, Left, (Author’s Translation from the German): TO THE MEMORY OF THE MEN, WOMEN AND CHILDREN, AND OF THE MEMBERS OF THE U.S. EIGHTH AIR FORCE, AND OF THE GERMAN LUFTWAFFE WHO DIED DURING THE AERIAL ATTACKS AGAINST SCHWEINFURT IN THE YEARS 1943 THROUGH 1945. The inscription reads, Right, IN MEMORY OF CITIZENS OF SCHWEINFURT AND AIRMEN OF THE 8TH U.S. AIR FORCE AND THE GERMAN LUFTWAFFE WHO LOST THEIR LIVES IN MISSION 115, OCTOBER 14, 1943, KNOWN TO THOSE WHO WERE THERE AS BLACK THURSDAY. An inscription in both German and English at the bottom of the Memorial reads, DEDICATED BY SOME WHO WITNESSED THE TRAGEDY OF WAR, NOW UNITED IN FRIENDSHIP AND THE HOPE FOR LASTING PEACE AMONG ALL PEOPLE. 16 JUNE 1998. (Photo Courtesy Wilbur Klint)

The occasion was one of utmost solemnity and celebration, with wonderful speeches delivered by the Mayor of Schweinfurt, the American Counsul from Munich, Georg Schäfer, and Bud Klint. Hundreds attended and the event received extensive coverage in both the electronic and print media. This was as it should be, for all men and women should take note whenever old enemies reconcile with the wish that there be no more war.