chapter four

THREE REBELS: ADVERTISING NARRATIVES OF THE SIXTIES

There is a time in every man’s education when he arrives at the conviction that envy is ignorance, that imitation is suicide, that he must take himself for better or worse as his portion. Insist on yourself. Never imitate. . . . Society everywhere is in a conspiracy against the manhood of every one of its members.

—VOICEOVER FROM “REEBOK LETS U.B.U.” COMMERCIAL, LATE 1980S1

satirist

Just as Bill Bernbach inverted the standard advertising industry practices of the fifties, advertising memoirs and handbooks of the sixties flatly contradict those of the fifties on everything from the value of science to their depiction of daily life in the business. They usually begin, strangely enough, by acknowledging the mass society critique and agreeing with the criticism of the advertising industry leveled by outsiders like Vance Packard. The work of the nation’s prominent Madison Avenue agencies, the authors of the sixties’ three great advertising narratives were quite willing to admit, was degrading, insulting, and unconvincing stuff.

If the Creative Revolution can be said to have unleashed any genuine geniuses on American culture, the title would have to go to San Francisco adman Howard Gossage. The ads he made, for odd clients like the Irish Whiskey Distillers Association, Fina gas stations, Qantas airlines, and Eagle shirts, are gems of wit and friendly joking; published almost exclusively in Gossage’s favorite medium, The New Yorker, they remain a pleasure to read forty years later. Although his ads never appeared on television, although he worked on the West rather than the East Coast, although his only book was published only in German (until 1987, when it finally appeared in English under the title Is There Any Hope for Advertising?), and although he died in 1969, Gossage inspired a following among American admen and practitioners of commercial art that persists to this day. This is curious, since Gossage produced as harsh an attack on American commercial culture as any generated by the Frankfurt School. In addition to being an adman, he was on the board of the leftist magazine Ramparts. He spoke out vigorously against the invasiveness of billboards and made hugely successful conservation ads for the Sierra Club (ads which, incidentally, were credited by some with having launched environmentalism2). His ad agency partner was Jerry Mander, who later wrote the anticonsumerism tract Four Arguments for the Elimination of Television. And his critique of the industry in which he labored and the consumer society which he had worked to build was biting in the extreme.

Is There Any Hope for Advertising?, which appeared in Germany in 1967, is an extended attack on the American advertising industry, to whose products Gossage applies in the course of two early paragraphs the words “fatuity,” “objectionable,” “degraded,” “trivial,” “boring,” “uneconomical,” and “the world’s dullest show.” Not only did the Reevesian repetition of simple USPs bore and irritate audiences, Gossage asserted, but it was a terrifically inefficient way to sell products as well, having caused over the years an “immunity” to develop in readers. “As the immunity builds up it costs more and more to advertise each year,” Gossage wrote. “It’s like narcotics, it must be taken in ever-increasing doses to achieve the same effect.” The social order of which advertising was the preeminent expression was similarly deranged. In an article he wrote for Harper’s magazine in 1961, Gossage described the affluent society itself as a sort of colossal Ponzi scheme. In the previous year’s elections,

Both parties swore fealty to ever-expanding production; this presumably based on ever-expanding population and ever-expanding consumption. Not only are all of these terms plainly impossible, but unnerving as well. Put like that, our economy sounds like nothing so much as the granddaddy of all chain letters. All you can do is hope to get your name to the top of the list, or die, before something happens (like peace) and the whole thing collapses.

Just as academics were coming around to the forbidden joys of popular culture, leading admen were learning to shun them. And for ten years, at least, the makers of American advertising would rank among the country’s most visible critics of the mass society.3

This skepticism would be the ideological point where the advertising of the sixties parted ways from its predecessors. In the gilded tableaux of so much of 1950s advertising, the world of consumer goods was a place of divine detachment, a vision of perfection through products. For Gossage, though, such ads were “shielded from real life,” making no effort to “engage their readers on a direct basis or attempt to involve them.” As with Bernbach and William Whyte, Gossage’s solution was to speak meaningfully to readers—“not in advertisingese, but in direct, well-formed English”—and until admen did so, “we will never develop the personal responsibility toward our audience, and ourselves, that even a ninth rate tap dancer has.” Of course, most ad agencies were prevented from speaking to readers in such a way by their layers of bureaucracy and their adherence to Reevesian theory; so, like so many other advertising writers of the era, Gossage posited an ideal adman who could circumvent entrenched ways. This was the “extra-environmental man,” a figure who regarded advertising as an outsider, whose “mind isn’t cluttered up with a lot of rules, policy, and other accumulated impedimenta that often pass for experience,” who was “unable to see things in a normal fashion,” who, like Gossage, regarded the American way of consuming as surpassing strange.4

The ads that Howard Gossage made are the best illustration of his ideas about the advertising industry. Like DDB’s ads for Volkswagen, his campaign for Irish Whiskey, which began appearing in the New Yorker in 1958, was a studied effort to deviate as forcefully as possible from the predominant advertising styles of the day. Appearing as a long series of installments, each one consisted of a full page of words, densely packed and forbidding, and written in a long-winded Irish-sounding vernacular as distant from “advertisingese” as the campaign’s eighteenth-century illustrations were from the immaculate, full-color renderings that accompanied the standard liquor advertising of the era. Although its copy refers again and again to the “dear” cost of advertising and to the “hard sell” in which the author apparently believes he is engaged, its method is decidedly soft—confiding, friendly, personal, and even a little hapless. Its layout is spattered with quaint effects like bracketed headlines and mail-in coupons for bizarre premiums. “Progress is perhaps our least important product,” one ad even announced.

Gossage’s campaign of 1961 for Fina gas stations seems to have been consciously invented to irritate Rosser Reeves. It was advertising, yes, but it was also a gorgeous satire of the pounding slogans and frivolous do-dads of the culture of consumption. Having discovered that most Americans scoffed at the various gasoline additives and other devices service stations then used to distinguish themselves, Gossage invented and then trumpeted to the skies a preposterous pseudo-USP: air for car tires that was dyed “premium pink.” Succeeding ads in the series recounted how earnest Fina officials were struggling to get the pink air to their various outlets, they offered pink asphalt as a contest prize, and they each concluded with what must be, with all its exaggerated courtesy, the creative revolution’s greatest anti-slogan: “If you’re driving down the road and you see a Fina station and it’s on your side so you don’t have to make a U-turn through traffic and there aren’t six cars waiting and you need gas or something, please stop in.”5

scoffer

The quintessential managerial operation of the Creative Revolution is perhaps best summarized in the trait once attributed to adman Jerry Della Femina by journalist Charles Sopkin: he “managed to bring chaos out of order.”6 In place of Martin Mayer’s objective and balanced prose style, Della Femina’s 1969 memoirs, From Those Wonderful Folks Who Gave You Pearl Harbor (the title is taken from a joke about a Japanese client) address the reader directly, often veering into exclamations, hip slang, sarcasm, and obscenities. The story of his life on Madison Avenue is told as a series of winding anecdotes rather than as a precise exposition of advertising lessons. His purpose is not to demonstrate how well the big agencies do their business, but how badly. The book is a classic debunking: taking note of certain romantic portrayals of the advertising industry in the first chapter, he emphasizes with a cynical sense of humor the business’s neuroses, the poor quality of most of its products, and the various ways admen’s careers may be destroyed. The literature of advertising had come full circle: after years of industry denials of Wakeman’s depiction, a successful advertising man was once again describing his profession in the terms made familiar by The Hucksters.

The corporate-style ad agencies that had been the heroes of Mayer’s and Reeves’s books are Della Femina’s villains; the “large, bad agency” where decisions are made by account executives and businessmen rather than by people who actually make ads. Nor are the traditional agencies institutions of placid, calculated order, according to Della Femina, but madhouses of fear and constant danger. The book opens by describing such an agency on the day an important account is lost. Panic sets in quickly as the jobs associated with that client disappear and the various account men scurry to find another company to take the departed client’s place. They boast of their friendships with people at comparably-sized businesses, their certainty of landing new accounts. And meanwhile they simply fire the “little people.”7 Della Femina devotes a whole chapter to the firing practices of the various agencies, noting in particular the instances of good workers being fired at the whim of an egotistical or deranged boss. Creative people are fired and replaced for a fraction of their salary by younger people. Entire departments are fired and refuse to discuss it with each other. Agencies hire special employees to do nothing but fire other employees. Presidents of companies are fired by officers they appointed. Other presidents fire everyone who stays at their agency for a certain duration to prevent anyone from becoming powerful enough to fire them. And when any of these people are fired, they find it very difficult to land another job. Fear, constant and mortal, is still the defining characteristic of the advertising business.

Della Femina’s cynicism also extends to the type of work he himself does. The creative departments, where the actual work of making ads is done, are populated not by reliable organization men, but by eccentrics. “Advertising,” he writes simply, “is the only business in the world that takes on the lamed, the drunks, the potheads, and the weirdos.” Admen that he knows skewer telephones with scissors and try to throw their desks out windows. One insists on working from four in the afternoon until midnight. Alcoholism is rampant. Bizarre costumes are commonplace, as are “dilated pupils.”8 Della Femina is even more cynical about the actual work of the industry. He speaks of the various package goods—the staple clients of Madison Avenue—and the campaigns that promote them (including his own for a vaginal deodorant) in terms of frivolous, needless exploitation:

The American businessman has discovered the vagina and like it’s the next thing going. What happened is that the businessman ran out of parts of the body. We had headaches for a while but we took care of them. The armpit had its moment of glory, and the toes, with their athlete’s foot, they had the spotlight, too. We went through wrinkles, we went through diets. Taking skin off, putting skin on. We went through the stomach with acid indigestion and we conquered hemorrhoids. So the businessman sat back and said, “What’s left?” And some smart guy said, “The vagina.”9

Like Victor Norman, Della Femina is unable to internalize the seriousness with which admen like Rosser Reeves addressed the minutiae of product differences, the drama of brand competition. Of a Ted Bates commercial for Certs candy that declares, “It’s two mints, two mints, two mints in one,” he sarcastically comments, “Oh, it’s a fantastic commercial, it is some claim to fame in the history of man. Two mints in one.” If Della Femina was the zeitgeist barometer he clearly believed himself to be, by the end of the 1960s, the American adman was not a touchy defender of consumer excess but a jaded scoffer contemptuous of the institutions of consumer society, scornful of the imbecile products by which it worked, and corrosively skeptical of the ways in which the establishment agencies foisted them on the public.10

provocateur

“If you’re not a bad boy, if you’re not a big pain in the ass, then what you are is some mush, in this business,” says George Lois.11 A fervent proselytizer for the Bernbachian way since he worked at DDB during the late 1950s, Lois was a leading practitioner, a conspicuous success story, and a living symbol of the advertising revolution that began in the early 1960s. Since then he has been a Madison Avenue Jacobin, pushing the business revolution to its antinomian end. While Reeves, Ogilvy, and others were denouncing the self-serving and unproductive expressions of art directors who were not properly controlled by rules and theories, Lois was indulging his considerable artistic skills without heed for industry conventions and making effective advertising by so doing. When advertising texts of the fifties advised executives to suppress the dangerous artistic impulses of their underlings, people like George Lois must have been who they had in mind.

If Bernbach was suspicious of statistics and critical of the priority of research at most agencies, Lois was positively aflame with anger at the institutional procedures that, he believes, make for the epidemic of bad advertising that has long prevailed on Madison Avenue. “Advertising, an art,” he wrote in 1991, “is constantly besieged and compromised by logicians and technocrats, the scientists of our profession who wildly miss the main point about everything we do, that the product of advertising, after all, is advertising.”12 Until the Creative Revolution, Lois insisted, the production of American advertising was smothered by rigid, repressive codes of dullness-inducing rules. The language he uses in his recent book to describe the prerevolutionary situation echoes the language of the mass society critique:

Advertising “instruction” available to artists could be loosely described as knee-jerk drills in constructing schematic advertising layouts. They were Prussian-style exercises, directed by hacks who preached the conventional wisdoms of advertising’s early days: large illustration above a headline above a block of body copy with a logo in the lower-right-hand corner. Even today, most print advertising follows this vapid pattern. Small wonder that the least talented people in advertising, incapable of innovation, create advertising according to this gospel.

Lois countered this repressive tradition by writing, matter-of-factly, “Advertising has no rules—what it always needs more than ‘rules’ is unconstipated thinking.” One chapter is titled, “To push for a new solution, start by saying no to conventional rules, traditions and trends.”13 For Lois, Bernbach’s suspicion of rules was an archetypal conflict between repression and liberation, “Prussian” order and American-style heteroglossia, the anal-retentive and the “unconstipated.” Bernbach celebrated difference; according to a 1970 profile Lois “can make the word normal sound like a social disease.”14

According to sociologists Paul Leinberger and Bruce Tucker, the defining characteristic of post-Organization white-collar workers is a powerful artistic impulse.15 For George Lois, advertising, as he practices it, is art. Lois is a graduate of Pratt; the dust jacket of his 1972 memoirs, George, Be Careful, depicts the hand and arm of Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel God reaching out to Adam; in 1977 he published a coffee-table art book called, simply, The Art of Advertising.16 More important, Lois’s professional practice seems to derive directly from Romantic ideas of the superhuman artist. He insists on the inviolability of his graphic productions, even though they are supposed to serve a commercial purpose. But artists were hardly comfortable in most places on prerevolutionary Madison Avenue, and Lois describes his life then as a constant war against the philistine managerial style of the fifties. According to his own 1972 recollections, he violently confronted superiors, whether other agency men or clients, whenever they edited or altered his work. Lois writes that when one ad he designed was changed without his approval, he felt “Personally defiled,” and physically attacked the man responsible. While working for one large, bureaucratic agency in the mid-1950s, Lois discovered that his work, under evaluation by an important WASP account supervisor, had been spread out on an office floor and walked upon. Again he was enraged:

I kneeled down and swiftly rolled up my ads, column by column, until I had them all in a tidy cylinder under my arm. The diagonally positioned desk of C. L. Smith sat like a fortress in the far corner, behind me. I had salvaged my ads, but I was still in a blind rage, incensed at the way my work was defiled. I gripped the overhang of Smith’s desk and with all the strength of my furious mood I flipped it toward Smith’s corner. The fortress landed with a deadly thunk on its forward side as drawers slid open and were jammed back into the falling hulk. My cylinder of ads was safely tucked under my arm as all the debris from the top of Smith’s desk crashed to the floor. My action was so sudden that a streak of ink actually surged from the desk’s executive well and hit the wall like a Rorschach splotch. But I had my ads, my work—and without looking back I quietly walked out of the room.17

Even the symbols of traditional agency practice and authority aroused Lois’s artistic ire. Like Jay Chiat snipping ties, Lois reveled in transforming the ink of fifties order into shapeless Pollock-like blotches.

Chafing under almost any sort of authority or hierarchy, Lois recalls how he broke again and again from the various agencies that employed him in the 1950s. In 1960, he left DDB to form his own agency with Fred Papert and Volkswagen copywriter Julian Koenig, the first shot in the long series of creative secessions that would define the decade. The sudden success of the trio’s agency, dubbed Papert Koenig Lois (PKL) and specializing in creative outrage, signaled the changing dynamics of American admaking. The key to PKL’s success, Lois insists, was its extreme organizational openness, its lack of constraints, bureaucracy, and established procedure, its allegiance to art rather than science. “The joint was unbefouled by mannerism,” he wrote in 1972, “and nothing could stop us. . . . We worked late because it was painful to leave its carefree atmosphere.”18 Lois explains his agency’s freedom in these simple terms:

“You start out by hiring people who are creative, then just give them room to do what they want,” I said. “You just sit down and work with guys. Also we try to hire people who will disagree with us. . . .”19

Disagreement was just part of the climate at PKL, where, as at DDB, creative freedom encouraged every sort of activity other than “normal” business operations.

The title of Lois’s 1972 memoirs is George, Be Careful, an admonition typical of the cautious advertising world of the 1950s. But George is never careful. He is an artist, and, as it has always been for artists in the twentieth century, outrage is the dynamic principle of his career. According to a 1967 issue of Advertising News of New York, Lois is “the archetype of the non-organization man,” and the usefulness of defying convention in spectacular ways is the book’s primary theme. Lois curses. He fights. He performs bizarre gestures to persuade clients to approve his outrageous ideas. He defies his superiors, rebels against conventional corporate order, and believes passionately, even violently, in the sanctity of his work as art. Whether standing up to recalcitrant clients or rankling under repressive account men, Lois refuses to live and work in conventional Madison Avenue ways. Lois recounts how his partner Koenig was pestered by a nosy client demanding to know how an ad would appear in a smaller format. “Julian held up the full-page layout and said, ‘Here’s how it would look’—and he tore it in half.” Lois insists that all of the people hired by PKL were similarly irreverent, and he goes out of his way to emphasize their eccentric habits. None of them was a WASP, and none came from the comfortable classes that dominated the industry in the 1950s. Their ethnicity and supposed penchant for fisticuffs earned them the nickname “Graphic Mafia” in the business. Lois reports that when Carl Ally, who would later go on to found another of the decade’s most successful creative firms, was interviewed for a job, he grew irate at Koenig’s questioning and said, “Fuck you, I don’t need this horseshit.” This prompted Lois to hire him. Admen at PKL curse and fight one another. One day they shred a man’s objectionable shirt while he is wearing it. Such tales would have been wildly out of place in the 1950s Madison Avenue accounts of either Vance Packard or Martin Mayer, but Lois recounts them with a certain pride.20

PKL was a dramatic success at first, with billings that grew from zero to $14 million by its third year, and it became the first advertising agency to sell stock publicly.21 But the growth of the business was uncomfortable for Lois, and in 1967 to “kick the curse of bigness”22 he walked out of PKL and set up another new shop. Lois’s explanation of his move was that while PKL’s success may not exactly have made it into an “establishment” agency, it had nonetheless been sufficient to transform him from a person who made ads—an artist—into a supervisor. “You know how much time I spent on creative work at PKL?” Lois complained to Madison Avenue magazine in 1968:

Between seven and nine each evening at home, because that was the only time I had to do it. The rest of the time, at the office, I was supervising the other creative people. It was different when PKL was billing 18 million. At that stage I was doing every stitch of the work.

Lois described the firm’s climate with a word of some considerable negative connotation: “The feeling turned from a truly creative to more of a normal agency.”23 In the big establishment agencies of the fifties, management and client-relations had taken precedence over creative work. But Lois had no interest in administration. His new partner, James Callaway, summarized the sixties vision of agency operations when he asserted in 1968 that in other industries, upper management made critical decisions, but in advertising “the really important decisions . . . are made by the copywriter or art director who creates the ads, because the ads are what advertising is all about.”

Lois’s scheme for Lois Holland Callaway, the agency he founded in 1968, as he outlined it to Madison Avenue magazine, envisioned the Bernbachian managerial style taken to an anti-organizational extreme. The three principals of the new agency were to do all of the “important” work of admaking and hire others to do anything else that was needed.24 The new agency was designed to be streamlined, to keep employees to an absolute minimum, and thus to maximize the creative freedom of the central trio. In a piece published five months after its founding, Newsday marveled at LHC’s billings relative to the size of its staff. “The customary ratio of staffers to billing is 7 to 10 for every $1,000,000,” the newspaper pointed out. “On this basis LHC should have something like 200 employees instead of 18.”25

The free and wide-open workplace was not just a matter of Lois’s personal preferences or his artistic disposition. He argues that openness is a necessary precondition to realizing the central element of his advertising style: outrage. His peculiar management beliefs and his shocking style are inextricably connected:

In order to be breakthrough, it [advertising] has to be fresh and different, it has to be surprising. And in order to do that, you need a talented art director and writer working together, who have some leeway and liberty to try to create advertising.26

In order for an ad to work, Lois argued in 1991, one had to cause outrage. Good advertising, therefore, is synonymous with rebellion, with difference, with the avant-garde’s search for the new:

I’m always pushing for a creative idea that has more grit than one has a right to expect, that rubs against sensibilities, that drives me to the edge of the cliff. That’s how you bring life to your work. The fact that something hasn’t been done does not mean that it can’t be done. Safe, conventional work is a ticket to oblivion. Talented work is, ipso facto, unconventional.27

Good advertising should “stun” the consumer, as modern art was supposed to shock, by presenting him or her with an idea that upends their conventions of understanding. When Lois presents his work to clients, he expects it to “cause my listener to rock back in semi-shock.” Good advertising is like “poison gas”: “It should unhinge your nervous system. It should knock you out!” Lois calls this the “seemingly outrageous,” and when used properly it should drive the sales message home:

Advertising should stun momentarily . . . it should seem to be outrageous. In that swift interval between the initial shock and the realization that what you are showing is not as outrageous as it seems, you capture the audience.28

Lois’s techniques necessarily militate against whatever happens to be acceptable at present. “The fact that others are moving in a certain direction is always proof positive, at least to me,” Lois writes, “that a new direction is the only direction. Defy trends and don’t be constrained by precedents.”29 The adman must live in perpetual rebellion against whatever is established, accepted, received. He must internalize obsolescence, constantly anticipate the new. It is not an exaggeration to say that there are no Lois ads that simply go through the conventional motions, like the ones studied by William Whyte back in 1952: in every single one an effort is made to assault the consumer’s complacency, the sense of the usual that he or she has developed over a lifetime of commercial bombardment. Of course, after a few such ads the conventions and routines are entirely reformulated, and the struggle goes on. The Emersonian adage could be updated to fit the creative revolution: He who would be an adman must be a nonconformist.

A good example of the Lois technique is the LHC television campaign for the New York brokerage firm of Edwards & Hanly (1968). Before this campaign, brokerage advertising was sedate stuff, grasping for respectability with long columns of solid-looking words.30 Edwards & Hanly, though, was a small and struggling firm, willing to do almost anything; at the same time Lois’s new agency, LHC, was looking for a way to advertise itself with a startling, controversial statement. The resulting television commercials which Lois, Holland, and Callaway wrote in one day and produced in three weeks used the testimony of athletes, children, and other unlikely authorities to address people’s basic need for brokers: to make money.31 In one spot, the boxer Joe Louis, who had famously lost millions, looked unhappy and asked, “Edwards & Hanly, where were you when I needed you?” In another, Mickey Mantle said, “When I came up to the big leagues, I was a shuffling, grinning, head-ducking country boy. But I know a man down at Edwards & Hanly. I’m learnin’, I’m learnin’.”32 Like other Lois campaigns, this one worked by pairing a serious subject with pop-cultural spokespeople. Lois described the episode in his usual manic style, exaggerating its offensiveness and celebrating yet another triumph of irreverence over stodginess:

The minute [the clients] left, the three of us charged into the elevator, laughing insanely, mostly out of relief that we had come this far with our first wild campaign for the stuffiest industry of them all without getting stiffed by a frightened client. We ran through the Manhattan crowds like three stoned kids, laughing and whooping all the way to the bank on Fifth Avenue.

The New York Stock Exchange, which strictly regulates the advertising of its members, was not long in forcing Edwards & Hanly to withdraw a number of the spots. When Lois, Holland, and Callaway appeared to defend their work, the contrast between their free-swinging, ethnic ways and those of the guardians of the Exchange’s honor was extreme. Lois quotes his partner Callaway’s description of the showdown: “Two micks and a Greek were arguing about a TV spot starring a schvaatza in front of a bunch of WASP’s.”33 The new capitalism was beginning to challenge the white pillars of order everywhere.

Perhaps Lois’s boldest use of the “seemingly outrageous” came during a mid-sixties television campaign for the New York Herald-Tribune. The campaign’s print ads used such volatile, mock-threatening lines as, “Who says a good newspaper has to be dull?” and “Shut up, whites, and listen.” Its television side, Lois recalls, consisted of commercials that ran immediately before the eleven o’clock news on the New York CBS affiliate. During each one, an announcer would briefly discuss the next day’s headlines, mention the newspaper’s new appearance—and then attack the institution of television news! “There’s more to the news than this headline,” the voice-over would say, “and there’s more to it than you’re going to hear on this program.” “I couldn’t believe that CBS was actually letting us get away with it night after night,” Lois wrote. But again the ads’ offensiveness caused the guardians of Organization to muzzle Lois’s creativity: according to his 1972 memoirs, they were one day seen by CBS president William Paley who, duly outraged, put a quick stop to them.34

the utopian imagination of the Detroit automakers,

Oldsmobile, 1961. This is as neat a vision of consensus order as one will find anywhere in American culture: Norman Rockwell landscape, patriotic colonial architecture, confident man, fawning wife, mirthful children, jolly firemen, and reassuring reminders of the jet-age military. Five years later an ad like this would appear to be from a different country.

so banal it’s surreal.

Calvert Whiskey, 1958. The headline suggests that most fanciful of product advantages: a whiskey that causes no hangover. But the art seems to be from a different ad–he’s partial to football and boxing, not sports known for producing clear-headedness. The copy, which is a study in emptiness (“Something wonderfully satisfying about the flavor, isn’t there?”) seems to have been written for yet a third. And what’s up with that giant glove?

enter doyle dane bernbach.

Volkswagen, 1961. Simple, elegant layout; simple, devastating sales pitch. The Volkswagen is never obsoleted, unlike those new American models that appear in the spotlights at the auto show. The light, humorous copy puts the ad’s explosive message across easily: Detroit is a fraud.

volkswagen versus mass society,

1966. It’s so practical, it inherently militates against faddishness and conformity. Notice the identification of the “avant-garde” with trendiness.

the anticommercial whiskey,

Calvert Whiskey, 1966. Eight years later, with the giant glove nowhere to be found, DDB is selling Calvert whiskey as the antithesis of empty, “Madison Avenue” promises. After having come up with what may well have been the most slickly meaningless product claim for liquor of all time (“soft whiskey”), DDB proceeded to denounce liquor advertising in general for its slick meaninglessness.

the airline of authenticity,

El Al, 1967. Airlines, too, could benefit from the DDB makeover. There are no Stepford stewardesses on El Al. Like Volkswagens and Calvert Whiskey, their planes are affectation-free.

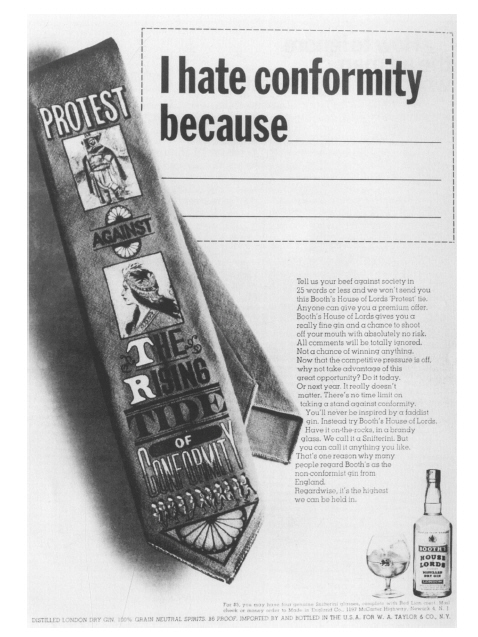

nonconformist gin,

Booth’s, 1965. By the mid-sixties, the zany creative style could be found even in ads for gin, the main ingredient of martinis. This ad for Booth’s Gin, which ran in an advertising trade journal, mocks as many aspects of the Madison Avenue lifestyle (ties, mail-in offers, “competitive pressure,” fads, martini glasses, the use of the suffix “-wise,” and, of course, conformity) as one can in such a constricted space. (General Research Division, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations)

Admen are liars,

but you are a discerning critic of pop culture, Fisher stereo, 1967. You can see through their puffery and falsehoods (if you can’t, ask an unaffected, down-to-earth guy like an “engineer” to help you), and you can even see through this one, too!

savage parody

of the utopian style and frivolous auto design of just a few years before. Volvo, 1967. The “throw-away” culture for which the Detroit automakers are responsible is worse than Volkswagen has been telling you: it’s actually “crazy.” Even though tailfins had been dropped by GM and Chrysler in the early sixties, they continued to appear for years in critiques like this one as a standard symbol of everything that was wrong with consumer society.

detroit strikes back.

Dodge, 1965. You say you’ve had it with Detroit-style consumerism? Then so has Detroit. Salvation is as easy as buying a new car: “Rise up. Break away from the everyday.” Dodge is leading “the charge on Dullsville.”

the mustang transformation, 1965.

Like the Dodge Rebellion, Mustang’s promises to deliver consumers from ordinary life were sexist, lighthearted and self-mocking. Later years would demand a more rigorous critique of consumer culture.

youngmobiles.

By 1967 the obvious symbol under which all of these different strains of revulsion with mass society could be brought together was youth. Remember, it’s the ideas that are young here, not the Oldsmobile owner.

buick populism,

1967. The documentary impulse in advertising. This corporation is an understanding friend, from their openness to your language to their gracious consideration of your needs to their realistic-looking models to their unadorned, sans-serif typeface.

“organization man” mutiny,

Oldsmobile, 1969. The promise is as simple as Volkswagen’s, if the execution is poor (Oldsmobile just couldn’t seem to get away from baffling terms like “Positive Valve Rotators”): this car rescues you from anonymity and bureaucratic malaise. Women, too.

creativity yes, youth culture no.

Hat Corporation of America, 1961. A flippant, self-conscious ad in the DDB style, but distinctly craven toward the masters of mass society (“They may be right, or they may be wrong, but there’s no denying that they’re in charge”) and hostile to rebel youth culture. The Beatnik pictured here is so dressed for failure that he even has a black eye. The hat industry started the decade striking all the wrong notes; by the end of the sixties it had been badly damaged.

youth culture, yes!

Love cosmetics, 1969. Hostility to affectation + suspicion of advertising + corporate populism + freedom, nature, honesty = Youth!

the uncola,

7-Up, 1969. Coke may have been the “real thing,” Pepsi may have identified itself with the young generation, but 7-Up went just a little farther.

Note here the blurring of management theory and product pitch: by offering reproductions of its billboards, 7-Up is permitting “unrestricted creative freedom.”

(© 7-Up and UNCOLA are marks identifying products of Dr Pepper/Seven Up, Inc. 1997. Courtesy of the John W. Hartman Center for Sales, Advertising, and Marketing History, Duke University Special Collections Library.)

backlash, 1966.

Volvo. Now Detroit’s promising youth, rebellion, and “Pizzaz,” but they’re still up to the same old tricks, and you’re the loser by it. An unusual ad in that it actually pictures the relationship of reader and advertisement, proposes that advertising manipulates and victimizes consumers, and offers itself as a ready-made subversion.

backlash, 1972.

Camel cigarettes. The sixties are over and now it’s the pseudo-liberating, youth-screaming styles of the Peacock Revolution that are the true markers of conformity–and of a particularly effeminate conformity as well. The real rugged individualists are . . . average guys.