chapter five

“HOW DO WE BREAK THESE CONFORMISTS OF THEIR CONFORMITY?” CREATIVITY CONQUERS ALL

Is creativity some obscure, esoteric art form? Not on your life. It’s the most practical thing a businessman can employ.

—BILL BERNBACH1

resisting the usual

For all of the sophistication of recent cultural theory, many of its practitioners still tend to identify the sins of the consumer order as “homogeneity” or an obsessive logocentrism. In the advertising industry, that order’s prime ideologist, however, these values were everywhere under attack by the mid-1960s. As a creative revolution followed in the wake of DDB’s artistic and commercial success, the advertising industry began to recognize nonconformity, even more than science or organization or standardization or repetition or regulation, as a dynamic element of advertising and, ultimately, of the “permanent revolution” of capitalism itself. Early in 1970, a columnist for Madison Avenue magazine discussed the industry’s realization of this principle. Although in “society” people “strive for . . . acceptance, conformity, anonymity,” advertising necessarily militates against these values, offering consumers vicarious fulfillment of their “dream” to “stand out, to excell [sic], to be idolized, adulated.” As Rosser Reeves had recognized, the basic problem much advertising faces is somehow to make products that are very similar to each other seem “unique.” That advertising can only succeed if it, too, is made somehow to stand out from a blizzard of other ads, each vying for the consumer’s attention. “To be successful,” the magazine held, “. . . one must emerge from the mass, walk naked among the clothed, take that first step towards success, towards that dream fulfillment.” The basic task of advertising, it seemed in the 1960s, was not to encourage conformity but a never-ending rebellion against whatever it is that everyone else is doing, a forced and exaggerated individualism.

Every company is different and should look different. To be afraid to advertise in a way which talks about real problems or real differences is to be afraid to look in the mirror. To balk at communicating differently from competition is to balk at moving ahead of competition.2

Addressing the “real” problems of society and outlining “real” differences, then, would be the story of advertising in the 1960s.

As the decade progressed, Bill Bernbach’s values of admaking and his revolutionary restructuring of the creative process spread rapidly through the sedate steel-and-glass boxes of Madison Avenue. The rage for creativity—which came quickly to mean an appeal to nonconformist rebellion against the mass society in ads as well as a nonhierarchical management style—was fueled partly by the demands of the admen themselves, who finally glimpsed liberation at the end of the corporate tunnel, but more importantly by the traditional buyers of advertising, the blue-chip clients of the big agencies who, impressed by the magic formula they saw in the Volkswagen (or Avis, or Calvert, or El Al) campaign, demanded similar work from their agencies. “‘Let’s get somebody like these guys and quit getting killed by General Foods,’” Jerry Della Femina imagines a Kraft executive reacting to a DDB ad. “The cry is going out all over town, ‘Give me a Doyle, Dane agency, give me a Doyle, Dane ad.’”3 The Creative Revolution may have questioned hierarchy, conventions of public speech, and the meaning of consumer culture, but it was fundamentally a market-driven phenomena. Remembering how his admaking philosophy was once denounced by the industry’s press, George Lois says,

That was the venom of the establishment. . . . Ninety-nine percent of the advertising came from the BBDOs and the J. Walter Thompsons, who were sitting there watching Doyle Dane’s advertising and my advertising, and they were furious, because their clients were saying, “Why can’t you do something like that?”4

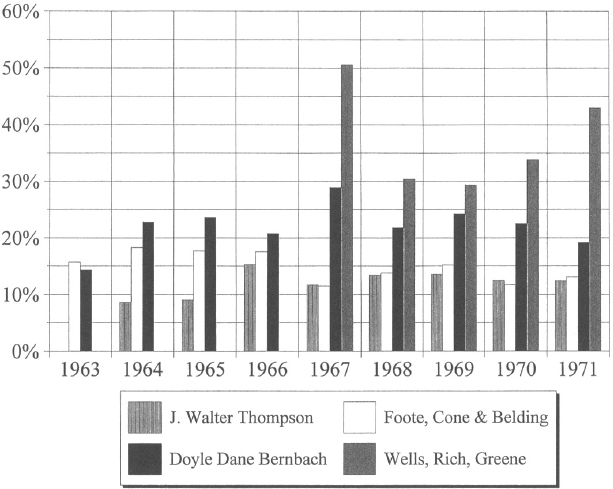

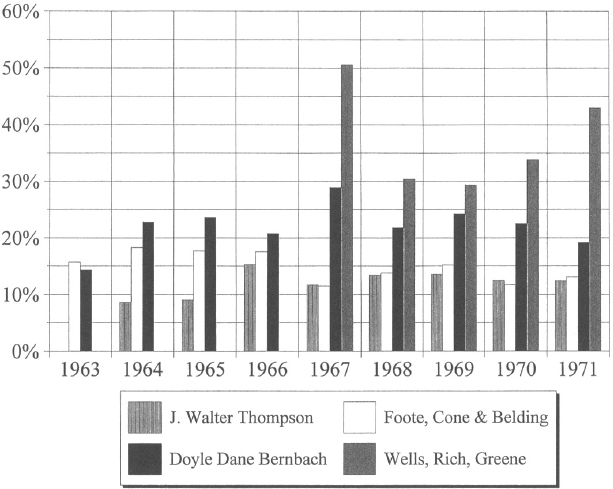

After fifteen years of predictability and utopian fantasy, American capitalism suddenly developed an enthusiasm for graphic sophistication, for naturalism, for nonconformity, and for willful transgression. Dozens of small, explicitly “creative” ad agencies appeared overnight, organized according to Bernbachian rather than the old hierarchical theories of management and promising to deliver the anti-establishment magic of the Volkswagen campaign. The large agencies scrambled to keep pace, reorganizing themselves into creative units, abolishing entire levels of hierarchy, and rushing to the corporate fore a caucus of young dissidents. The industry grew phenomenally during the decade. Expenditures in the six largest media (newspapers, magazines, radio, television, outdoor, and farm newspapers) grew from $4,736 million in 1953 to $7,164 million in 1960 to $12,237 million in 1970. The more meaningful indicator, though, is found in the relative profitability of the large, establishment agencies that had symbolized the industry during the fifties and the smaller, less hierarchical creative agencies. Figures for J. Walter Thompson and Foote, Cone & Belding (the successor to Lord & Thomas, the one-time employer of Frederic Wakeman) remain fairly comparable from 1966 on, hovering usually between ten and fifteen percent (see figure 1). During the same period, though, Doyle Dane Bernbach consistently posted profit margins above twenty percent while those of Wells, Rich, Greene, the superstar creative firm of the late sixties, actually exceeded fifty percent in 1967, their second year of operation. If only because of the blunt market logic of profitability, the age of organization was over, at least temporarily, on Madison Avenue; that of the small, flexible agency was beginning. And with the new trends in management would come a new cultural dispensation: it was to be the age of corporate hip.

fig 1 Profit Margins of Publicly Traded Advertising Agencies, 1963–71

ideologues of difference

Although there were always admen who disagreed strenuously with the admaking and management styles championed by Bernbach and Lois—the followers of Rosser Reeves spent the decade posturing as hard-headed businessmen under siege by romantic dreamers—by the mid-1960s the doctrines of creativity had swept the field. Admen from agencies large and small were producing articles, books, speeches, and, most important, ads that echoed or magnified Bernbach’s hostility toward “science,” to rules and to the priority of marketing data over creative inspiration. By 1965, the Creative Revolution had turned the industry’s theories and management practices on their head as Madison Avenue entered a period of unrestrained rule-breaking and idol-shattering. One demonstration of the change came when Reeves was elected into the “Copywriters Hall of Fame” in 1965 and, with characteristic truculence, challenged the Advertising Writers Association of New York (AWANY, which sponsored the award) to define creativity. The organization’s leaders fired back with equal conviction that “AWANY must, by its nature, come out against ‘formulas’ for advertising. By promoting individuality AWANY feels the standards of professionalism in advertising are raised.”5 That was hardly the harshest riposte faced by Rosser Reeves in those times, however. In February 1966, this quintessential adman of the fifties retired from his position as chairman of the Ted Bates Company, in a move that was interpreted by Advertising Age as a signal of changing ideas about creativity.6 A later version of the story recounts the Reeves downfall as a much nastier bit of corporate skulduggery. In Conflicting Accounts, a 1997 book about the rise and fall of Saatchi and Saatchi, the British mega-agency that acquired Bates in 1986, advertising writer Kevin Goldman asserts that Reeves was sacked rather than retired—and that “the agency so wanted Reeves out that it paid him $80,000 annually for ten years to keep him away.”7

By the mid-1960s the anti-principles of creativity had become rule-book stuff in their own right. In a 1966 handbook for copywriters, a Young & Rubicam creative leader instructs readers that “The first rule for copywriters is to be suspicious of rules. Rules have a way of turning into ruts.”8 Even more telling evidence of the new antinomian climate was a house ad for the Geer, DuBois agency, authors of the unremittingly hip campaign for Foster Grant sunglasses, that appeared in the New Yorker in 1967. Under a blank TV storyboard (a type of layout paper used to plan television commercials) are listed the classic steps to producing a television commercial of the standard Reeves style of the 1950s: “1. Open by getting attention. 2. Establish news value. 3. Briefly show what the product is,” and so forth. After the eighth step, the copy reads, simply, “It’s with good rules like these that bad commercials are made.” The industry’s storyboards were being symbolically wiped clean: a new beginning was at hand.9

The authority of “science” in advertising theory had also diminished considerably by the mid-1960s. In 1966, advertising writer Nicholas Samstag contributed a long essay to Madison Avenue magazine entitled “You Can’t Make a Good Advertisement Out of Statistics.” By then the argument that advertising was “more an art than a science” had definitely been won, he noted, but the traditional hostility of business for something as nebulous as art had made this difficult to put across: “the men who pay for advertising are ill at ease in the presence of artists.” But, Samstag continued, “Don’t let the pie-charts and research mumbo-jumbo fool you. An advertisement is a seduction,” and “there are no objective standards against which the efficacy of a seduction can be measured in advance.” Samstag’s vision of the advertising revolution, which was replacing Reevesian science with Bernbachian aestheticism, could easily be read as a manifesto for the larger revolt against the constraints of the mass society.

Marketing should be an emancipator. It should unlock locks and cut bonds by suggesting and implying, by hinting and beckoning, not by defining. It should be the agent that frees, not the agent that imprisons. . . .

In brief, we need more and more affirmative, plastic, humanistic, refreshing research, less and less scientific authoritarianism. . . .

Forward researchers! You have nothing to lose but your dogma.10

The passage is a remarkable document of the sixties, startlingly reminiscent in tone and language (it would be indistinguishable if the words “marketing” and “research” were removed) of the decade’s other overheated celebrations of “emancipation” from “scientific authoritarianism.”

The primary goal of unleashing all of this creativity was not to overthrow capitalism, of course, or even necessarily to make the workplace happier, but to jump-start the engine of change—the “permanent revolution”—that drove consumer culture. Following Bernbach’s celebration of “difference,” admen in the sixties awoke to the virtue of nonconformity. By the mid-1960s, talk about creativity and perpetual innovation was ubiquitous in industry literature. The ideologues of Madison Avenue now insisted, contrary to the standard practices of the preceding decade, that the adman internalize an automatic mistrust for received ideas. Arguing in 1966 that “the ‘new’ is inevitably the product of the impatient individual,” Sherman E. Rogers of the Buchen agency advised his colleagues to understand “restlessness and discontent” for what they were: the wellspring of “the new.” For Rogers, the good adman has nothing to do with “status quo-ism,” or the agency types of the 1950s like the “play-it-safer” and the “hat-in-hander,” those “who view the Jerk and the Monkey [popular dances] with wide-eyed alarm, who have not listened to Bob Dylan with the idealistic ears of the young.”11 Asserting that “we copywriters and art directors should be the most obvious disciples of change,” Hanley Norins, Young & Rubicam’s most fiery creative partisan, reaffirmed later that year the decade’s commercial antinomianism, its skepticism toward whatever had already been decided. “What we need,” he wrote, “is an attitude of distrust toward our own ideas. . . . As soon as you have an idea, try to disprove it.”12 Here, as in so many other aspects of the business, management theory spilled over unproblematically into the actual content of advertisements: Not only was this willingness to defy convention de rigueur for creative personnel, it made a fine brand image as well. For Chester Posey, creative director of the gigantic McCann-Erickson agency, creativity was defined as an embrace of what he called “the unexpected,” a general contrariety that set an ad off from the mass-cult babble surrounding it. “I believe that our biggest risk in advertising is the risk of being expected,” he wrote. “I believe that effective advertising must be incompatible with an indifferent opinion of a product. . . . that it must be interruptive, disquieting, challenging, surprising and unsettling.” Nor was this a simple matter of announcing “all new all over again.” Finding the unexpected meant constantly searching for unusual angles to “that good dull product that we deal with every day.” It was “a philosophy and a way of thinking.” And, like Rogers’s “impatience,” it was a concept he chose to illustrate with youth culture icons, a collection of which accompanied Posey’s 1965 Ad Age article on the subject.13

By 1966, the new way had even triumphed at J. Walter Thompson, citadel of the advertising establishment. Concerned about the challenge from DDB and the other creative agencies, JWT circulated a series of “Creative Forum Papers” within its offices, aiming to instruct its employees in the fine points of the new style. The installment for November, 1966, a short essay entitled “Conform with the Non-Conformists,” written by associate creative supervisor R. Beverley Corbin, laid out the problems facing creative workers at big agencies. Since advertising has to “do what everyone else isn’t doing” in order to work, it was the adman’s duty to “do it differently” and to confront clients and co-workers who were afraid to venture out of their gray flannel preserves, to “break these conformists of their conformity.” In the past, admen had felt pressure to blend into the organization, to resist showing individuality, to “seek out a technique of advertising someone else is doing successfully and latch onto it like a Remora latches onto a Shark.” But the days of conformity were over, at least in theory. Corbin encouraged his colleagues to “try to stand out like a healthy thumb amidst a bunch of sore fingers.”14 By 1966, even Dan Seymour, the president of J. Walter Thompson, had been convinced. “We are dedicated to constant discontent with the status quo,” this head of Madison Avenue’s most status quo agency said. “We don’t believe in styles or schools. . . . The only thing we know for sure is that there is no such thing as a J. Walter Thompson ad.”15 Nonconformity was fast becoming the advertising style of the decade, from the office antics of the now-unleashed creative workers, to the graphic style they favored, to the new consumer whose image they were crafting.

the creative workplace

As advertising theory increasingly reflected the Bernbach line, agency organization and management made a sharp about-face as well. The Creative Revolution affected not only the way admen thought and the ads they produced but their everyday business practices. If the rule-smashing “New Advertising” (as one writer called it in 1970) that was then in such demand—the antimarketing iconography of nonconformity, difference, and individualism—required decentralized, nonhierarchical anti-organizations, then Madison Avenue would positively trip over itself to deliver just that. If the advertising world of the 1950s was, as Randall Rothenberg describes it, “a fundamentally conservative industry,” an industry whose primary task was placating the whims of the client, that of the 1960s would be dominated—symbolically at least—by the eccentric creative genius, defying convention and going to the wall for his rule-breaking ideas.16

According to the heated industry rhetoric of the sixties traded back and forth through the pages of Advertising Age and Madison Avenue, the Creative Revolution was fought out along something resembling class lines: the division being between creative workers—art directors and copywriters—and the account men who communicated with clients. Jackson Lears maps onto this division his story of the endless war between managerial and carnival values in advertising. The books of Reeves, Mayer, and Ogilvy had all assailed dreamy and overcritical creative workers. But in the sixties, the tables would be turned. According to creative partisans, it was the traditional power of the account executives, who were said to know little about admaking itself, that made so much of their industry’s product boring and ineffective. Not coincidentally, account men were also believed to be predominantly WASPs, wearers of gray flannel, and consumers of the famous “three-martini lunch.” The terms with which George Lois excoriated “the hack marketing people” in 1971, are extreme, but they give a vivid idea of the hostility between the two camps:

They don’t like the way we work, the way we talk, the way we dress. They don’t know anything about advertising or how good advertising is created. They hold this business down. They help to create the bad advertising we are inundated with.17

Jerry Della Femina’s chapters on agency dysfunction and the idiocy of such institutions as “creative review boards” are all aimed at account executives. And when questioned in 1968 by Marketing/Communications magazine about “the current state of the agency business,” one particularly hip adman replied that

The creative spirit is dampened by account men in rep-tie blindfolds. There is much frustration. . . . a lot of creative people wasting their lives where their creative ability never gets by a plans board. I can see creative types going on strike . . . or a mass walkout of 200 or 300 creative types in this business.18

For Lois and others, the struggle between account-management and creativity was “war,” an all-out conflict of lifestyles and philosophies.

It was a battle whose issues and outcome would define the industry throughout the 1960s. Creative workers denounced the science and research of the fifties and demanded instead freedom and autonomy in the workplace. At the same time, they insisted that their products and decisions be accorded the respect due the work of professionals. For some commentators in the 1960s, it appeared as though creativity might prevail unconditionally.19 Demand was great for the new type of advertising; to meet it, an army of creative personnel broke away from the large firms to found their own less-structured agencies. The large “establishment” agencies began to reorganize themselves along the new lines as well. Young & Rubicam, the industry’s second-largest agency, promoted Steve Frankfurt, a 36-year-old arts-oriented television director to its presidency. The other pillars of the “establishment” rushed to build creative cells, to shake up the tired ranks of their executive corps, to loosen up creative restrictions and rationalize the creative process. Martin Mayer had already noticed the magnitude of the change by 1965 when he wrote that while “in 1954 the nation’s seven largest agencies were all run by ‘businessmen’; ten years later, four of them had copywriters at the helm, and two of the others had moved ‘creative’ men into the heir-apparent positions.”20 In August, 1969, with the Creative Revolution in full swing, Newsweek estimated that almost a hundred new firms had been inaugurated in that year alone.21

Most of these new agencies, of course, would never grow to the size of J. Walter Thompson or Doyle Dane Bernbach. Nor would they provide all of the various services (media buying, research, testing, etc.) that larger agencies performed. But while they rarely represented blue-chip clients, these new, unstructured, and intensely creative agencies set the tone for the advertising of the decade. With struggling clients willing to try anything and little bureaucracy to hinder them, the creative shops—“boutiques” in the parlance of their doubters, “hot shops” in that of their supporters—expanded the boundaries of advertising, pioneered a thousand new techniques and formulas, and opened paths that their larger competitors would soon follow. And some of the firms founded in those years—Wells, Rich, Greene; Carl Ally; Scali, McCabe, Sloves; and Chiat/Day—did eventually become prominent industry fixtures.

Trade journal reports of the doings of the small, “hot” agencies invariably focused on three aspects of their work—three fantasies of corporate antinomianism that continue to define much of the language of advertising to this day (Dan Wieden’s reminder to new workers that “chaos is creative” and that his agency functioned like a “slime mold” is more typical than it sounds). First, they were described as Theory Y havens, virtually unstructured organizations, places of anarchic lawlessness, frenzied rule-breaking, corporations that somehow did without intrusive, dragging bureaucracy. Thus photographer Onofrio Paccione complained to Madison Avenue in 1965 about the big agency experiences that had led him to strike out on his own. “Committees, committees, committees, and then you go back to your own office and solve the problem,” he said. At Leber Katz Paccione, on the other hand, Paccione was able to develop ideas himself from start to finish, and actually took all of the photographs the new agency used in ads, a system which, the magazine noted, “gives him complete creative control over the execution of the ads. There is no distortion of an idea by having it pass through many hands.”22 “Establishing an environment in which creative people can flourish” was the theme of a January, 1966, article on Delehanty, Kurnit & Geller. Here, too, creativity was said to be privileged over organization. There were very few bureaucrats to interfere with true commercial inspiration, allowing one art director to sum up the creative process in these idealistic terms:

After knowing all he can about a product, the art director and the copy chief are ready to create a selling concept. The art director must then work in an environment where his intellectual and intuitive ideas may be expressed. Where his graphic skills and tastes can be appreciated. And where he knows his final product will not be destroyed by insensitive committees, frightened account executives or egomaniacal clients.23

A third agency even dared to de-organize itself to the point of defying Bill Bernbach’s creative team system, the basis of creative agencies. It was just too structured, too orderly by 1966 standards. The agency president, Martin Solow, assailed what he called the

Fettish [sic] for teaming up creative people, such as an art director with a copywriter. We don’t believe in rules. We simply work together. Maybe three copywriters will sit down and solve the problem. Our art directors have given us some of our best headlines. Bright things come out of bright people.

And the duty of the agency’s management was simply to provide the surroundings and the materials in and with which those “bright people” could function best.24

Second, each of the small firms that dealt in creativity wore the aura of Bernbachian client-defiance. So intransigently did the new adman believe in the professionalization of his calling and the correctness of his creative judgment that he would rather resign an account than submit to the humiliation demanded by industry captains like Evan Llewelyn Evans. Thus, Esquire editor Harold Hayes notes in one of the blurbs on the dust jacket of George Lois’s 1972 memoirs that relations between admen and clients have become much more volatile: “The image of the soul-rotted ad man, trembling before the wrath of his client in order to keep his ranch house in Westport, is not the image of George Lois.”25 Lois proudly recounts how he climbed out an office-building window in order to convince a recalcitrant Matzoh manufacturer of his advertising expertise and details his refusal to bow and scrape before the powerful head of Seagrams, Samuel Bronfman: “I wasn’t about to play the foot-shuffling adman who swallows his pride and does a jig for a dozing client.”26 By the mid-1960s, Lois’s defiance was commonplace among creative types. As one of his “nine statements for art directors,” Georg Olden, the 1965 chairman of the New York Art Directors’ Club, included this commandment: “I do not do everything I am told. Unless I agree.”27 Carl Ally, who left PKL to found his own agency in 1962, blamed the badness of mainstream advertising in 1966 (by then it was a fairly standard creative complaint) on agencies’ traditional tendency to indulge clients’ whims rather than stand up for what they know is the right approach:

The real flaw is lack of commitment. The well-they-won’t-buy-that mentality. We don’t ask what the client wants. We test everything on ourselves. If we like it, it’s good. If we don’t, it stinks.28

Scali, McCabe, Sloves, one of the most successful creative agencies launched in the 1960s, once took this adamantine stance toward clients to its logical conclusion, resigning an account when the client declined to take the agency’s advertising advice. The agency made a practice of never offering “more than one execution of an ad or commercial to the client,” Madison Avenue observed in 1970, and even then “when copy is to be changed for technical reasons, the writer who wrote it changes it, not the client.” So when Scali, McCabe, Sloves disagreed with one of its largest clients about the nature and direction of a new campaign, the agency simply gave up the account rather than accept the client’s dictation. As president Marvin Sloves recalled,

We [the agency people] talked it over. It took us five minutes to decide to resign the account. It wasn’t anything petulant. We just disagreed with them and, since we regard ourselves as the experts, we had to stand up for what we believed in.29

Creativity’s third identifying feature was, of course, the stunning divergence of its ads from the formulas of the 1950s, formulas which creative admen believed, almost as a matter of faith, were still strictly enforced at the big agencies in the 1960s.

the establishment

The favored term among revolutionaries for the big agencies against whose bureaucracy and inspection they felt so much rancor was “establishment.” Into the 1970s, creative admen continued to mount an array of accusations against them in the industry press: the establishment was the preserve of the repressed and fearful account men, where ads were still produced by what Jerry Della Femina called “the assembly-line method.”30 As he described it, copywriters at the establishment agencies were told the client’s sales objective and churned out a number of possible headlines and pitches. These were then given to art directors to illustrate.

Now the art director is . . . chained to his desk; they don’t want art directors roaming the halls at large agencies. . . . He usually is between forty and fifty years old but even if he’s a young guy his mind is fifty. . . . The copywriter says, “We got to have a layout by this afternoon to show to the creative director.” . . . It’s in the hands of the creative director by that afternoon and that’s it. There’s little relationship between the art director and the copywriter. They hardly know each other.31

In “the establishment agencies” as elsewhere in the technocratic society, the artistic spirit was said to be imprisoned by the vast, impersonal organization, individuality was suppressed, and everyone was old. Creative partisan Robert Glatzer recounted in 1970 how corporate pusillanimity had given the large agency Foote, Cone, and Belding the nickname “Stoop, Prone, and Bending.” Its abject willingness to please clients “has tended to attract docile, gelded Mad-Ave types to FCB, the security-minded androgynes of this malevolently sexual business, who would rather submit than fight a client bent on raping a campaign.”32 The accounts of both Glatzer and Della Femina were exaggerated, of course. But the “establishment” problems of the big agencies were acute enough to propel them into a revolution of their own.

As creativity became the most hotly-sought element of advertising, even the most factorylike, statistics-dominated firms gave in to the new wave and entered upon a frenzy of creative reconstruction. Large agencies “raided” smaller ones in hopes of luring away creative superstars with more generous salaries; they established more or less autonomous creative groups to produce material along DDB lines; they rejuvenated their management corps; and they leaped headlong into the endless theorizing about the nature of creativity that fills the advertising texts of the period.

Jack Tinker & Partners, an experimental “think tank” that was developed by the enormous McCann-Erickson agency in 1960, was a small group of advertising specialists headed by a veteran McCann copywriter and charged with developing special marketing strategies for McCann clients. But in 1964 Tinker began to make advertising on its own, for a list of clients which eventually included Alka-Seltzer, Gillette razors, and Braniff airlines. Launched on the antibureaucracy, antirules credo of the hot, creative shops, the group was the first and one of the most successful attempts to capture for a large agency the benefits of a small, unstructured organization. The original Tinker Partners had been executives caught up in the day-to-day supervision of others and unable to devote their time to the actual stuff of advertising. One later recalled, “Jack was spending 80 per cent of his time in meetings, reviewing other men’s work when he should have been spending his time creating.” The goal of the Tinker experiment, then, was to find “if a small team of advertising executives with proven ability, if sequestered from the committees, review boards and daily mundane agency chores, could come up with fresher, brighter and more creative solutions to advertising problems than seemed possible under the normal agency structure.” Naturally, the group’s antihierarchical nonstructure was described in communitarian political terms that sometimes marked the era’s political attacks on the technocracy. One of the partners, Myron McDonald, characterized the business as a “democracy.” Jack Tinker himself described it as a “community in which outstanding talents can exist together.” Mary Wells, who first came to prominence under Tinker’s tutelage, voiced the group’s suspicion of bureaucracy, a standard creative complaint by 1965, the year her remarks appeared in Madison Avenue: “We don’t want eighteen people passing on information. The only effective way to do creative work is for the creative person to see a commercial all the way through himself.”33

The success of the Tinker group and its rapid imitation by every other “establishment” agency marked a transition on Madison Avenue equally important as the rise of the independent creative shops. It was a declaration—first by McCann-Erickson and its gigantic parent company, Interpublic, then by the other corporate agencies—that the age of Theory X had ended, that Organization was on its way to extinction, to be replaced by a stripped-down, flexible, “democratic” arrangement that privileged creative nonconformists. Before long, the new way had been adopted even by J. Walter Thompson, the great institutional foe of creative excess. In 1966, Thompson reorganized itself to meet the needs of “creative people, who almost instinctively rebel against the formal, structured organization,” finally bringing art, copy, and television people together into one of six putatively autonomous “operating groups” where freedom was the order of the day. Madison Avenue magazine, ever optimistic about creative advance, hailed the change as “the replacement of the debilitating ‘production line’ atmosphere for a new sense of total involvement with each account.”34 At Benton & Bowles, the change required two separate waves of corporate radicalism, one in 1966 (“We came to the conclusion that for the best results our creative people should work together in an intimate relationship as total advertising people, working on creative problems together from start to finish,” Al Goldman, the company’s creative director, was reported to say) and another in 1970, when an outside “creative Messiah” was hired to clean hierarchical house in a flurry of firings and what today would doubtless be called “re-engineering.”35

In addition, many of the “establishment” agencies hired leading creative rebels away from the small shops where they had distinguished themselves, with each building what Madison Avenue columnist Jerry Fields called its “own brand of ‘Tinker Toy’ or Creative Island.” But none of the changes made much difference to self-proclaimed real creative rebels, who, like Fields, continued to complain of being “emasculated . . . with many-splendored layers of creative review boards, committees, brand managers, product managers, and other filtering strata of management executives on the client and agency side” throughout the decade.36 Although Jerry Della Femina publicly derided what he called the “zoo concept,” he was himself acquired by none other than the Ted Bates agency, the hard-sell holdout from which Rosser Reeves would soon depart.37 Tales of creative stars’ defections to the big agencies and their subsequent unhappiness under the Organization’s yoke are a standard trope of the literature of the period, an almost predictable cautionary tale for the new corporate age. After losing its top four creative workers to McCann-Erickson at one point, Delehanty, Kurnit & Geller president Shepard Kurnit said in 1969, “The offer was so good that if I didn’t own the company, I would have gone along with them.” None of the four stayed at McCann for long. Each went through a variety of positions at various agencies until two of them returned to Delehanty, Kurnit & Geller.38 In 1968, J. Walter Thompson hired Ron Rosenfeld, one of DDB’s star copywriters, to construct a new creative group within the giant agency. A year later, Rosenfeld resigned from Thompson offering advertising writers yet another opportunity to muse on the incompatibility of genius and hierarchy. Writing in Madison Avenue magazine, Bob Fearon pontificated about the inherent conflict between the people who create “an awful lot of the best advertising of late” but who “sense things” rather than rely on research; and the rigid, overorganized agencies of the corporate establishment who know simply “how to deliver an acceptable product on time.”

Being oriented to giving clients what they wanted, agency leaders tried to graft on a free-spirited, gut-oriented creative quality to their already existing, highly-stratified institutions. They brought creative names in. They said things were going to be different. In almost every case the chemistry was wrong. In almost every case the import was asked to fit himself into the system. The system was not willing to bend.39