1

CORPORAL RICHARD NUMMER

Weapons Company, Twenty-eighth Marines, Fifth Marine Division

For forty years I never even talked about it or nothing, but soon as I seen that flag I knew I was the one put the hole in it. Not too many people know there’s a hole in the flag.

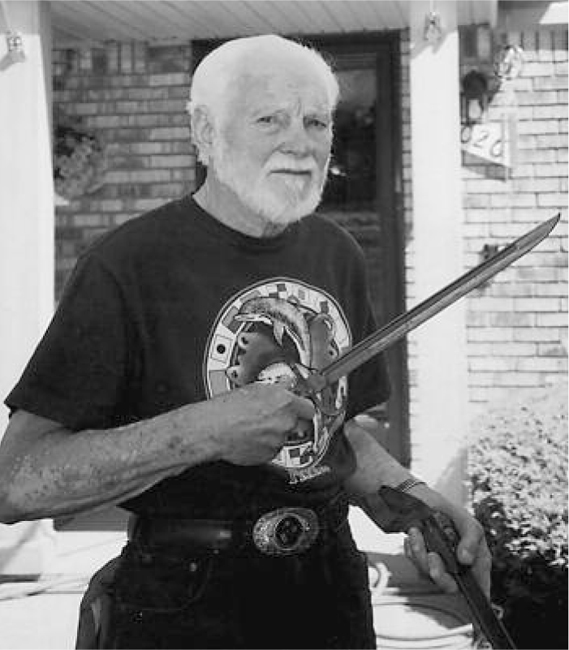

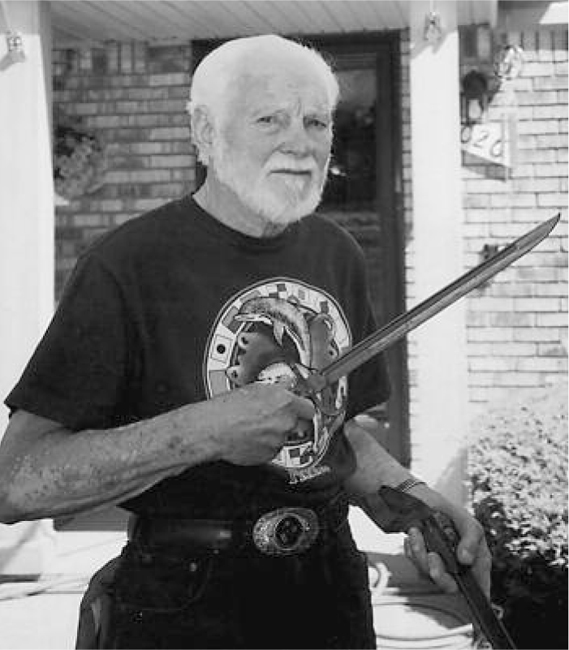

Standing in the backyard of his home north of Detroit in the summer of 2006, eighty-year-old Richard Nummer holds the bayonet he took from the body of Siguo Kubo, a Japanese soldier he shot dead during the campaign for Iwo Jima in February–March 1945.

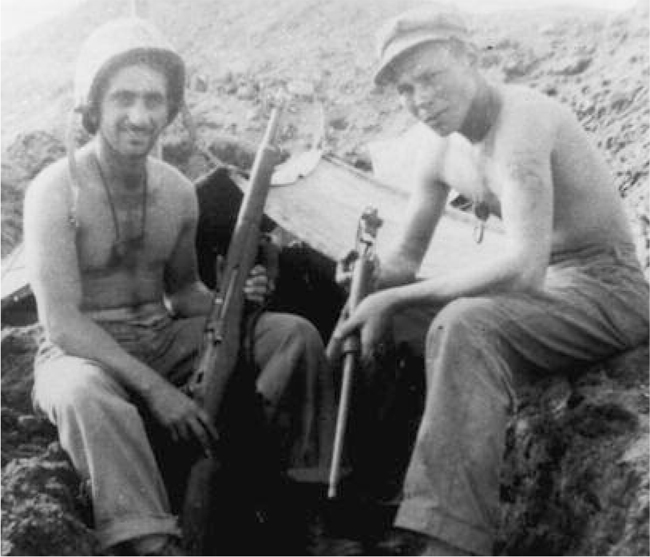

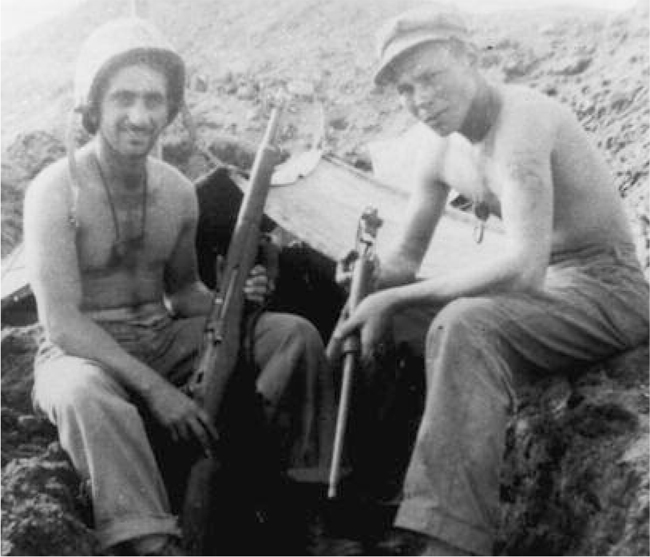

Corporal Richard Nummer, right, and his foxhole buddy Al Esposito, from New York, have their picture taken atop Mount Suribachi on February 24,1945, with a camera recovered from the body of a slain marine.

I met with Richard Nummer at his modest home in East Detroit in the summer of 2006 before the Marine Corps opened its new museum in Quantico, Virginia. He was eighty years old, lively and talkative. We hit it off immediately. It turned out he had quit school to join the Corps in 1942. He added that sixty-three years later, in 2005, he received an honorary diploma from his alma mater, East Detroit High School. “They finally got the government to give you a thing saying they appreciate what you did. So I got my honorary diploma. All those years later I finally became a high school graduate.” Richard laughed when he said this. “I still got the cap and gown they gave me.”

“I went in with the fifth wave. When we got off the ship, we went around and around in circles, rendezvoused, so they could start letting different waves go in, you know, one right after another. So when we went in with the other waves, it seemed like there was no action at all. But just about the time I got there, around ten o’clock or ten-thirty, we start running in, that’s when they really opened up.

“I was in a Higgins boat. The ramp went down in front. Our gun, a thirty-seven millimeter on wheels you pulled with a truck, was on the other boat, an LST [landing ship, tank], I think. At that time I was with Headquarters Company of the Twenty-eighth Marines.

“When I hit the shore, like I say, we ran up. There were not too many bodies when we first landed. I saw about ten. The first wounded guy I seen his jaw was gone. He was running back, and a couple corpsmen were trying to tackle him so they could get morphine into him. I don’t know if he made it or not.

“But as you ran up, you’d tap a guy on the shoulder, and he’d run up a little farther and you’d get in his hole. He was supposed to get up and go to next hole when you tapped him, like leapfrogging. So I get in this hole and tap the guy on the shoulder and, nothing. He was gone. There was shell holes all over from the aircraft. I jumped in this one hole. It was pretty good, but right above me I could see all this sand getting hit with bullets from up above, coming right down. Anyhow, I laid there. You couldn’t move. Every time you’d just move an arm or something you’d draw fire.

“I was pinned down there for maybe five minutes. I had a New Testament with some of the Psalms included, here in my pocket, so I opened that up, and I read the Twenty-third Psalm. And I just finished that, put it back in my pocket, when a shell hit, and I don’t know nothing till the next day. [Richard had been knocked out cold.] I guess it was the concussion from that shell hitting close by. There were bodies all around there. I lay there twenty-four hours. Anyway, next morning I woke up, and when I got up to where my group was, the rest of the company, the sergeant just shook his head. He said, ‘We had you down KIA.’ Killed in action. ’Cause I was laying there with the dead.

“Our gun maybe didn’t get hit, but it could have got stuck in sand. You couldn’t use them until they got some bigger vehicles to pull them out of the sand and up onto the beach. Each ground section of artillery was supposed to be with one of these companies.

“Anyways, Combat Team Twenty-eight crossed the neck at the base of the island and turned toward Suribachi. They got the Thirty-sevens up, and they were firing at anything they could see on Suribachi. They kept putting the shells in so fast and shooting them that the lines and grooves were just round after a while, and the barrels were no good at all [heat melted the rifled grooves inside the barrels, so the shells could not rotate. The grooves give them accuracy and velocity]. They were almost disabled. So we got stuck with infantry in the attack on Suribachi, and then, four days later, on February 23, the first flag went up. Louis Lowery got that first photograph. I knew him real well. He was on the ship with me. He slept almost right next to me. So, oh boy, that didn’t mean the war was over for us, but at least we got something going. The whole thing was supposed to take three days. I was there thirty-seven days, the whole time, and one day more.

“I didn’t go up with Lowery on the first flag raising. Some of us decided we was going to climb up Suribachi for a closer look, so we started going to the top. It probably took us forty-five minutes. Suribachi was pretty much taken out when we went up. We got there about the same time as this group arrived for the second flag raising. And they was just putting the flag up. We saw it go up, and we were just walking around up on top, looking down. A lot of pictures were being taken, but nobody knew this was going to be anything famous. We went up there because that’s where our group was. We were up there maybe an hour or so, and they decided our outfit, the Twenty-eighth, had got hit so bad we had to wait for replacements. And they said, ‘You’re going to stay right here.’

“So we were the first marines to sleep on top of Suribachi, six feet from the flag. I have a picture of my buddy and me sitting there. My buddy Al Esposito from New Jersey found a camera in the pack of a dead marine, and we had our picture taken with that. I was six feet tall and weighed a hundred sixty. We were taking turns on guard duty. Every hour we’d wake the other one up, kept changing like that. We was the closest foxhole to the flag, which was like right here, off my right shoulder. So he just got to sleep, and I kinda dozed off. At that time this was probably the safest place on the island because the rest of it was all downhill. There were about forty of us up there. Anyway, I heard this noise and I turned around and I thought it was a Jap, so I shot. But it wasn’t a Jap; it was the flag, snapping in the wind. I told Esposito next morning, I said, ‘Jeez, look what I did.’ He said, ‘What the heck did you do that for?’ I says, ‘Well, I thought it was a Jap.’*

“If you ever go to Washington, D.C., that flag is in the Navy Yard. Both flags are there [they have since been moved to the new Marine Corps Museum in Quantico, Virginia]. The first time I went for an Iwo reunion was twenty years ago. Reagan was president then, and we went to White House, met him and his wife and the first George Bush, and then we went over to Arlington Cemetery, where they got the flag raising statue, and soon as I went in that museum and seen the flag, I knew.

“For forty years I never even talked about it or nothing, but soon as I seen that flag I knew I was the one put the hole in it. Not too many people know there’s a hole in the flag. It’s right there in the second stripe. Here it’s probably the most famous picture ever taken, and I stuck my little hole in it. I should have been court-martialed. At that time, of course, nobody knew it was going to be famous, not until we got back to Hawaii a month later and seen the pictures and all.

“I knew right away, but all those years I never told anybody. In fact, the Marine Corps don’t even know about it. This guy was here last December [2005] it was the first time I ever told anybody about it. He come here and like interviewed me. They’re coming out with a picture, and this is the guy that does Clint Eastwood’s sound and all that. He was here, and he came here to try get this worked into the picture. But after he left, I got a phone call from him saying the picture was too far in the making, so it probably wouldn’t be mentioned.

“We were up on Suribachi five days while we waited for reinforcements. We lost five hundred ten men in four days of fighting. The reinforcements came on February 27, which was my birthday. I turned nineteen on Iwo Jima. We’d go down every day to work on the graves detail. They’d give you big black gloves that reached up to your elbow, for picking up the dead. That was our job. We’d pick up these bodies and put them on the truck, and off they’d go. They’d bury them in trenches. They were all brought back to the States later on.

“You saw some real bad sights there. No masks, and the smell and the flies were terrible. This one guy we picked up, somebody said, ‘There’s John Basilone’ [Basilone was a notable marine who’d received the Medal of Honor for action on Guadalcanal]. He wasn’t in the Twenty-eighth. I think he was in the Twenty-sixth or Twenty-seventh. He got it the first day I guess, but he laid there for all that time. A lot of the bodies were there for five days already. We didn’t fool with dog tags at all. You got your name stenciled across your back. For every dead Jap, I seen twenty-five dead marines easy. The Japanese would pick up their dead at night and drag them inside the caves, and we never knew exactly how many we got.

“A lot of times we’d lose two or three marines and cover them up with a blanket or a poncho. During the night the Japs would come and crawl in there, and some would take their uniforms off so you didn’t always know if it was a marine or not. Then the burial detail would come around. When we was on burial detail, we always had to watch out there wasn’t a Jap among ’em waiting for us, with a rifle or a grenade, whatever they could find. They’d try to get as many of us as they could.

“We just piled the bodies on the truck, and then they took them to where the cemetery was going to be. We did that for five days. We were walking around almost like zombies, you know? We had all this death on our mind, and we knew it was going to go on farther, and is this the end of us or what? We did this, and went back and forth to the beach to get supplies and stuff.

“We finally got into combat when we got down to the other end. We were on the front lines there. I had an M1 all the time. At night we’d put our thirty-seven millimeters in a row and put canister in, so if the enemy came, you could wipe out a whole bunch of them. But they never made a banzai attack except on that last day. Some days you stayed right where you was. All day long you didn’t move.

“We were down to the other end about a week, and one night off in the distance I could see somebody running around. We had different password codes. You’d yell ‘tree,’ and the person was supposed to answer with the name of a tree. And then you’d yell, ‘president,’ and the answer would come back: ‘Roosevelt!’ So quite a ways off here this guy come running. It was just getting dark. Two buddies in the hole with me, and I had the first watch that night. It was going to be an hour off, an hour on.

“This figure kept coming closer and it was getting darker, and I said to the guys, ‘There’s somebody out there, but I think it’s a marine.’ And they said you don’t want to shoot another marine, but he shouldn’t be out there. So he come closer. A hundred yards away was a lot of rocks and stuff, and he kept coming, coming; he had a rifle, got closer and closer, so pretty soon he got close enough to where he could hear me, and I yelled out, ‘Tree!’ And he’s supposed to yell back, ‘Oak,’ or whatever. ‘President!’ Nothing. ‘Car!’ He’s supposed to yell back, ‘Ford,’ or whatever. So then I started over. About twice I went through the thing. Nothing. So then I said, ‘Bukyosterol.’ That means ‘Drop your weapon.’ But he kept coming, and he’s almost right here. And the guys got up and said, ‘Shoot!’ My finger just froze on the trigger, and down he went. So that was the first one I got.

“Now he laid in the rocks, and I must have got him in the belly somewhere. I thought I killed him, and now I’m really shaken up because I thought it was a marine. So he started talking in Japanese. We didn’t know what he was saying, but farther on you could hear the other ones answering him. So he was trying to give away our position. We started throwing flares out there to see where he was. Meantime the whole group was all lined up with our guys. We knew they were coming. One of them hit the trip flare, and that lit up the field right in front, so quite a few Japs got killed. Next morning my lieutenant came up, his name was Manning, Robert Manning. He come up, and he said, ‘Who had the machine gun last night that started all this?’

“They said, ‘That was no machine gun. That was Nummer over there, with his M1.’ So he come over to me and shook my hand and said, ‘Good going, kid.’ He was from Bougainville and different campaigns before that. He says, ‘Go on out there now, and any souvenirs on him, they’re yours.’ So I went out there. ‘Wait a minute!’ he says. One of the guys brought a rope, put the rope around his leg and pulled it, and sure enough, he had two or three grenades underneath. If he hadn’t told me that, I would have gotten blowed up. That was one of the tricks they had. He probably shoved them under himself as he was dying. Those grenades were little black things as big as your fist that just had a piece of rope, and you pulled that out and put it underneath you and it wouldn’t blow. Sometimes they’d hit them on their helmet to get them started.

“The grenades blew him up. I got his wallet and his bayonet. I still got the bayonet in the other room there. Then the lieutenant says, ‘Well, you probably saved some of these guys’ lives. I’ll talk to you about it later on.’ I didn’t know if I was going to get some kind of medal or what.

“He left, and this was a terrible thing: He left, and he wasn’t gone long. He said, ‘You try to get some sleep now.’ So I got in the hole and I just about went to sleep and they woke me up. They said the lieutenant just got killed. And he wasn’t that far away from us. The reason he got killed he was crawling out to another guy laying there wounded and he was pulling him back. A sniper got him. It took us another two, maybe three days just to get to his body.

“One of our sergeants was named Duffy, from New York. There was this other kid named Hood. He drove the lieutenant’s jeep. Here the war’s going on, and the two of them get into a fistfight. They couldn’t get the lieutenant’s ring off because his hands were all swelled up, so the sergeant said, ‘We’re going to cut his finger off to send his wife back his ring.’ And the other guy, Hood, said, ‘No, just cut the ring off.’ So they got in a big fistfight over this. We were aboard ship when we heard his wife just had a baby. He never seen the baby.

“Before we landed on Iwo, I had boils all over, so they put me in sick bay aboard ship, and the doctor come in and said, ‘We got a new drug we’re going to try on you; it’s called penicillin.’ So I was one of the first to get penicillin. They shot you in the rear end; I think I got three of them, and all the infection concentrated in one big boil on my knee. Even when I was on Iwo, I had boils pretty bad. A corpsman said, ‘You’re in more pain than some of these guys that got hit,’ and he told me, ‘We can get you off the island.’ I said, ‘No, you’re not getting me off the island, not for boils.’ So I stayed right there. Why leave if I was still in good enough shape to fight? Just because you had boils? Did I think I was going to make it or not? Every night you’d say, ‘Well, I wonder if this is going to be it.’ You never knew.

“I got a little story about Ira Hayes [Hayes was the Pima Indian who helped raise the second flag and whose life was romanticized after he died drunk in an irrigation ditch on the reservation in New Mexico in the 1950s. A movie about his life was made starring Tony Curtis, and Johnny Cash had a hit song called the “Ballad of Ira Hayes”]. There were six guys in that flag-raising picture, and three of them got killed before we left the island. Bradley was left, Ira Hayes and Rene Gagnon. Bradley, his son came to one of the reunions. He’s the one that wrote the story about Flags of Our Fathers. But Ira Hayes was the only one I knew real well. After we got back to Hawaii, they went on the seventh war loan drive in the States, and he got drinking quite a bit, had his problems with drinking. They were making a big hero out of these three guys, and Ira Hayes just couldn’t see it. He said, ‘Anybody could do the same thing we did. It’s the dead guys that should be . . . ,’ so anyway, they sent him back to us.

“He was probably in the States three, four months, and he come back to our outfit. In our tent we had one of the code talkers, his name was Thompson. And Ira come into the tent, and everybody shook his hand, one thing and another. He started drinking right away, beer, you know, we had it in the tent. And he wouldn’t leave until all the beer was gone. If there was any left, he’d shove it in all around his belt. He’d be gone for days, nobody knew where he was at. It’s a shame.”

[Richard shows me a Japanese flag inscribed with various cities and explains.]

“After the war ended, I had occupation duty in Japan, nine months in Sasebo. Iwo Jima was the only battle I was in, but right after that we was getting ready to hit Japan and the bomb went off, which saved a lot of our lives. From Sasebo, not long after the war was over, we went to Nagasaki, where the second atom bomb was dropped. We were drinking their water and everything else. I was home about five years when I woke up with a gray streak. What the heck? The doctor said, ‘I think you had a slight stroke.’ My one eyebrow on the side was gray. They didn’t know about this radiation stuff at that time. I got out a corporal in July of ’46. When I got back, I couldn’t even get a beer: I wasn’t old enough.”

[When the book The Spearhead, relating the history of the Fifth Marine Division, came out, Richard’s name was not in it. He wrote to Washington and received a letter from Lieutenant Colonel H. W. Edwards at the Historical Branch, written on March 15, 1954. The key paragraph reads: “As a member of Weapons Company, 28th Marines, Fifth Marine Division, you sailed on board the USS Talledega for Iwo Jima, at sea 1–4 February 1945, at Enwietok (sic) in the Marshall Islands 5–6 February, at sea 7–10 February, at Saipan 11–16 February, at sea 17–18, arrived and disembarked for action against the enemy at Iwo Jima 18 February. You were engaged in action on Iwo Jima from 18 February (sic) until 26 March on which date you embarked on the USS Winged Arrow to return to base. You sailed from Iwo Jima on 27 March.”]

[Richard has one last story.]

“I had this wallet from this guy that I shot that night when the lieutenant was also killed, different things, so forty years later I saw all this stuff that I had. It was no good to me, so I thought I’ll send it back. I was all over different places, Japanese restaurants, and I was trying to get this stuff sent back. I was in Denver at a car show, and there were these three Japanese. I didn’t know if they were Japanese, Koreans, or Chinese so I asked, ‘Any of you guys Japanese?’ One says, ‘Yeah, we’re Japanese.’ So I says I got some stuff I’d like to send back to Japan. One guy says, ‘I’m going back in a month, back to Japan,’ and he says, ‘I’ll take the stuff with me.’ So I packed it all up and sent it to him in Denver, where he was at, and he left for Japan. About a year later I still hadn’t heard anything, so I was really disgusted. I had his address and everything, so I wrote him.

“And lo and behold, the same day I wrote him I got the first letter, from the daughter of this guy that I’d shot. She was forty years old, born after he left. Never knew her father at all. I got the letter here from her. She was so happy that she knew finally what happened to her dad.

“Besides the wallet, I sent diaries and different stuff, flags that had names on them.”

[Here is the handwritten letter from the daughter.]

Dear Mr. Nummer:

Allow me to write to you. My name is Mrs. Kimie Sato, a daughter of Siguo Kubo, who was a soldier died on Iwo Jima. I received my father’s notebook and three articles from you via Mr. Yamamoto six years ago [sic]. I heard you will go to Iwo Jima on March 14. How I wish I could go there and see you and say my thanks to you. However I cannot go there because of many restrictions. I was very excited and my heart was choked with the memories of my grandparents and my mother who died in 1981 when I handed the articles left by my father six [sic] years ago. They are my treasures for me now.

As you know I was born ten days after my father had departed for the front.

Thank you very much for your kindness and also I want to express my heartfelt thanks for Mr. Yamamoto and the Welfare Ministry. I received many congratulations from my friends and my relatives after the newspaper reported the ceremony of the return. I hear you are ill in bed. How do you feel these days?

Although I guess you had a pain of both physical and mental injuries I am sure that your warm and heartfelt kindness will impress the deceased and their families. I am praying for you that you may get better quickly for your friends and your family and you will have good days. If you go to Iwo Jima on March 14, please contact Mr. Takada if possible who will join the ceremony there.

Thank you again and I hope you will feel better soon.

Sincerely,

Kimie Sato

“That was the year I went to Iwo Jima—1995, the fiftieth anniversary. When I got there, the plane landed, and we was the last ones to get to where they had the ceremony. They announced my name on the loudspeaker to come to the podium. So I went to the podium, and there was a package for me. Now here I get a package and I don’t know—a hand grenade?—what’s in there. My son and I got on the side and we opened it up and she had a nice tie for me, coasters, a tablecloth, different stuff she was so proud for me to have. Some thought I was wrong by sending the stuff back, but I don’t think so. It was no good to me, that stuff, but to her it meant the whole world.”

Did she know Richard Nummer had shot her father?

“No, I never did tell her that. Couldn’t do that.”

*The use of the word Jap to describe the enemy was commonplace during the war, and it is repeated throughout this text by the marines who fought at Iwo Jima. The correct word, of course, is Japanese.