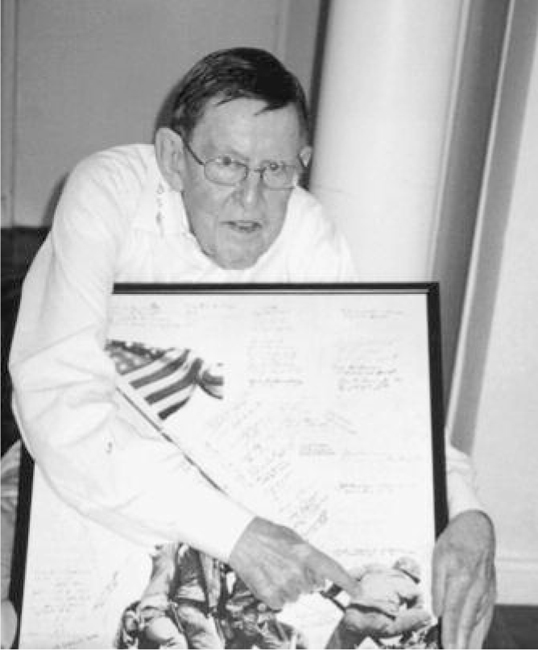

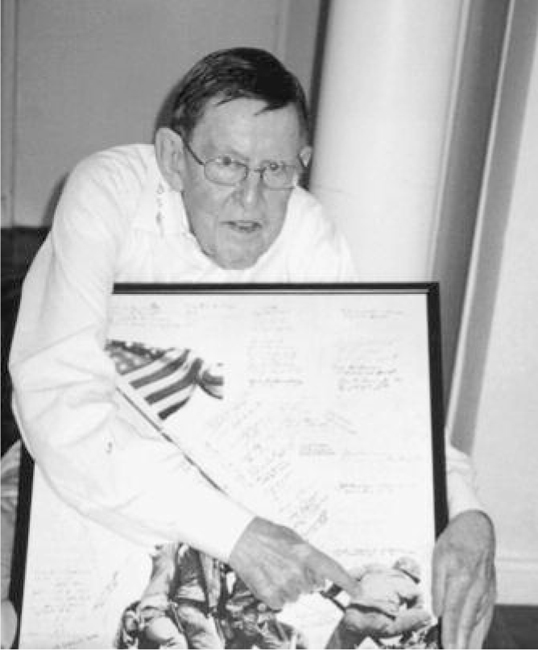

Fred Haynes holds a photo of the flag raising, signed by members of his outfit. His right hand points to his fellow Texan Harlon Block. Haynes is the author of The Lions of Iwo Jima, the story of Combat Team 28 on Iwo Jima.

Operations Officer

Twenty-eighth Marines, Fifth Marine Division

Some days, if we made one hundred yards, we were really doing it. On our side we had to cross corridors, and when you do that, you get enfiladed. At Iwo it was from the back, the front, and both sides. That’s why we lost so many people in the north end, particularly in fighting for Hill 362. We attacked every goddamn morning.

Fred Haynes holds a photo of the flag raising, signed by members of his outfit. His right hand points to his fellow Texan Harlon Block. Haynes is the author of The Lions of Iwo Jima, the story of Combat Team 28 on Iwo Jima.

Young Captain Fred Haynes takes a cigarette break on Iwo Jima, March 3, 1945. The photo was taken during the attack on Hill 362A and the taking of Nishi Ridge. His Bronze Star citation speaks of his “outstanding service” in helping plan the invasion and for “coordinating the regiment’s ship-to-shore movement,” adding that he frequently “braved heavy enemy fire to obtain valuable tactical information” on terrain over which his regiment was to attack.

Fred Haynes, who was eighty-five in 2006, was a captain and operations officer during the Iwo Jima campaign. He later became a general. When I interviewed him in January 2006, he was one of three from the battle who had become a general and was still alive. As an operations officer during the battle, he was involved in day-to-day planning and indeed devised during the battle a strategy that may have saved a great many lives. Haynes joined the Twenty-eighth Regiment out of Quantico and was never wounded, though he served in three different wars. He retired a major general in 1977, after having commanded the Second Marine Division at Camp Lejeune, North Carolina, and the Third on Okinawa. In 1958–59 he founded the Combat Veterans of Iwo Jima, with a membership of about seven thousand veterans and their families. A little-known blood disorder, hemolytic uremia, hospitalized him from December 2003 to May 2004. He was unable to walk for a year and half afterward. With his balance uncertain when he did get back on his feet, he fell and suffered compression fractures of three thoracic vertebrae, leaving him unable to stand up straight. He was strong and active, nonetheless, and got around as well as most on the return to Iwo Jima on March 8, 2006. I was on that trip as well.

Captain Fred Haynes received a Bronze Star for his service on Iwo Jima even though in all thirty-six days of the battle, he never fired a shot. “I carried an M1 rifle because I wanted to look as much like a private as I could; the Japanese were very careful about targeting officers. They would bang away at ’em very quickly. I was on Hill 362 with Lieutenant Colonel R. H. Williams at the peak of that battle early in March. I was right on top of the hill and a Japanese ran out of a cave intent on doing bodily harm to us. Williams’s runner, Yates, carried a thirty-eight-caliber revolver in a shoulder holster. Where he got it, I have no idea.

“Anyway, I went to shoot this Japanese, pulled the trigger, and nothing happened. So Yates pulled out his thirty-eight and killed him. The body was out in front of the hill. We had another runner with us, and he wanted to shoot this corpse. I gave him my rifle, and he was starting to aim it when Williams told him—and this was an indicator of how we indoctrinated people—Williams said, ‘God damn it, you don’t shoot corpses anytime! So put it down.’ So he did. Then I checked the weapon. There was no ammunition in it. I had gone all the way to that point in the battle without ammunition.

“I came on active duty with the Marines not long after Pearl Harbor. I had been doing graduate work at Southern Methodist University for a master’s in the new science of limnology, the study of inland waterways, now a well-known environmental science. I had actually graduated, in June of 1941, and later that year, probably December, I was doing some research in the library stacks and I saw a book called Fix Bayonets! by John Thomason. He was a captain in the Fifth Marines at Belleau Wood and Château Thierry. The book is a classic, supergood. I took it off the shelf and read it. I made up my mind that if I had to go to war, I’d be a marine.” [Colonel Charles Waterhouse (Chapter 12) was similarly inspired by Fix Bayonets!]

“Two Marine officers came through our campus to sign up potential graduates. I got on their list and was called to active duty the first of February 1942. I went to Quantico with three guys from Texas Christian University. All of us had played football. I played freshman ball at SMU before the coach urged me to give it up, and I became a track athlete. I played center and linebacker, and I only weighed one sixty-three. Our SMU team played Stanford in the Rose Bowl January 2, 1941. A lot of guys with significant football backgrounds fought at Iwo Jima. Our regimental commander, Colonel Harry Liversedge, had been an All-American tackle at the University of California at Berkeley. Liversedge was one of these guys like Cheney [Lieutenant Colonel Chandler] Johnson. Liversedge always wore his helmet, and he never carried a knapsack. He rarely used leggings. After D-day he took his leggings off. He wore a tank officer’s shoulder holster and carried a forty-five. He was one of those guys you need on the battlefield. He was a big man. He weighed about two fifty-five, two sixty. He was six-three or six-four. Even for those days he was pretty big. He had a kind of a loping stride. We called him Harry the Horse. He was a relatively quiet man.

“Combat Team Twenty-eight consisted of three infantry battalions, a weapons company, a headquarters company, and the Charlie companies of each of the combat support units, the pioneers, the tanks, the medics and the engineers, and usually we had the Third Battalion of the Thirteenth Marine Regiment, which was an artillery support unit. So we had about four thousand men. We walked off the island with about six hundred when the battle was over.

“Combat Team Twenty-eight landed on Green Beach at H hour. Our initial mission was to cross the narrow neck, about seven football fields wide [seven hundred yards], as rapidly as we could, then turn south to assault and seize Suribachi. I was responsible for making sure our boat waves were properly organized at the line of departure and dispatched on time to make the assault at nine o’clock. The first waves, the amtrac waves, were followed by, as I remember, two waves of Higgins boats, known as LCVPs [landing craft, vehicle, personnel]. Those were the organized waves. The Navy had patrol craft at both ends of the seaward line of departure, four thousand yards off Green Beach, and we had a ship-to-shore communications net operating from the command ship. It would indicate when each wave was to be at the line of departure and then the time, like at nine-five, nine-ten, and so forth, that the waves were to leave for the various beaches.

“There were probably seven waves ahead of me when I landed. I went ashore about nine-fifty with Colonel Bob Williams, who was the regimental executive officer. The last scheduled wave landed about nine-thirty.

“The Fourth Division was on our right, and on my right was the Twenty-seventh Marines. They had two battalions abreast. We landed in a column of battalions. The first battalion had the immediate mission of getting across the narrow neck. We had an excellent naval gunfire plan, really superior, and we pushed our troops up against the naval gunfire. We even had a few casualties from the gunfire, but not many. The combination of our previous training and the high caliber of the people we had in the First Battalion enabled us to cross this narrow seven-hundred-yard neck in about an hour and thirty minutes. They really smashed it.

“Back in California and Hawaii, when we were training, only about ten of us knew we were going to attack Iwo and Suribachi. We did amphibious landings at Pendleton and San Clemente, and when we got to Hawaii, we went through the whole cycle again before we left for Iwo. We picked a bubble on the slopes of Mauna Kea about the same height as Suribachi. We took engineer tape, used it to delineate lines where mines had been cleared, and formed the end of Iwo around that bubble. We would line up our troop units by boat team and walk them at the same speed, roughly about three miles an hour, and when they came to this tape, each boat team would deploy and follow the maneuver to get across the island. And then the Second Battalion would move in on the left. We had excellent, totally realistic training, and while the youngsters didn’t know where we were headed, they knew damn well they were going to do something like that. We were just going to go hell-for-leather straight across. We thought the First Battalion was practically ruined by the time they crossed the island. And of course the confusion on the beach as the troops moved inland was incredible. This was far worse than anything I ever experienced in three different wars. It took us about three or four days to figure out how many we had lost. I think we lost like three hundred men out of thirty-two hundred in the regiment on D-day. I’m one of the few people who lived through this battle without a wound and who started from scratch with the formation of the regiment and the combat team and continued with it through the occupation of Japan.

“Kuribayashi, the Japanese commander, was a really smart general. He waited until our units got on the beach, including Williams and Liversedge, the commander of Combat Team Twenty-eight. Within minutes, Kuribayashi put all his artillery and his heavy mortars on these beaches. It was chaos.

“But we got in and formed a command group on the beach with Liversedge and Williams. In the very late afternoon—and I’ll never understand this—Liversedge said, ‘You know, we’ll have to move to a better place where we can command this unit.’ So about one hundred of us, communicators and all, stood up and walked across the neck, almost halfway, to where we could see both beaches, and not a soul was hit.

“It was not quite dusk. And the next morning the Japanese pinpointed us and dropped a mortar barrage on our command group, killed our regimental surgeon, and blew the legs off one of our uniformed correspondents.

“I’d never been in battle before, and I didn’t know whether I’d panic or what would happen, but I found out quickly that I didn’t flap very easily. About ten-thirty we felt that it was absolutely essential to get our Third Battalion, which was being held back as a division reserve, back in under our control because a gap in the line had developed. The First had crossed the island, the Second had turned left, and casualties were very heavy. There was a lot of confusion, and this gap had opened between the right flank of the Second and the left flank of the First.

“We told General [Major General Keller] Rockey, the commander of the Fifth, it was absolutely essential to get the Third in, so we started landing them, about ten-forty, and they came and filled in the gap. By the close of D-day we had all three infantry battalions, all of our thirty-seven-millimeter guns and all our seventy-five-millimeter half-tracks, with the exception of one thirty-seven that had been blown up and sunk coming in.

“The weasels, small tracked vehicles, were the prime movers for the thirty-seven-millimeter guns. The Navy would not allow us to put a weasel and a gun in the same boat because they said it would overload it. Colonel Liversedge wanted to land eight thirty-sevens in the scheduled waves. We persuaded the Navy to let us overload the landing craft, so we devised a means of putting the gun on top of the weasel so we were able to double the number of thirty-seven millimeters that we got ashore in the initial waves.

“The seventy-five-millimeter half-tracks were good-sized weapons, and we had trouble getting them off the beach. We got a couple bulldozers and were able to move the half-tracks and a couple tanks that had got stuck. I’ve never seen anything like that black sand since. It was the consistency of percolator-grain coffee, and you’d sink up above your ankles in it. There were three terraces, or three levels of sand, on the beach. We got steel mats put down by the close of D-day, but the beach continued to be just utter confusion.

“The beachmaster for the division was a Navy commander who later became the first violinist of the San Diego Symphony. He was really an interesting guy. He’s dead now, but he was terrific. He was a no-bullshit type, and he got it done, but how he did it I’ll never know. Our supply system was a little bit different than it had been earlier in the war. We pushed everything up. We didn’t wait for somebody to say, ‘I need more ammunition.’ We pushed ammunition based on rough calculations, straight on up to the battalions as quickly as we could.

“Each amphibian tractor carried a predetermined packet of essentials, like a crate of grenades, two boxes of sixty-millimeter ammo and two boxes of eighty-one and about four boxes of machine-gun belted ammunition. The minute that amtrac got above the waterline, their instructions were to throw this stuff out on the beach, which they did. And that saved our butt on that first night and the next day because the marines all knew they could go back down there and get whatever they needed and get their butts back up there.

“We were able to dig foxholes about two feet deep. This was the middle of the winter, in February, and it was in the northern Pacific and it could have been very, very uncomfortable, but the whole island was a volcano, and once you got down six or eight inches, the temperature was very pleasant. Many of us would dig a little hole and put a can of C rations in it, and next morning you’d open it up and you’d have warm beans.

“There was no natural water on the island, and we were quite lucky because our Navy made water aboard ship. The Japanese only had what little they could catch, and it didn’t rain very much. By the time we were about a third of the way up the island, they were getting a hard biscuit a day and about a cup of water, terrible water. In my judgment, the Japanese officers were criminal in continuing this battle; they tortured their own men. These poor bastards got a biscuit and a cup of water a day, and they had to work underground in temperatures of one hundred ten to one hundred twenty degrees. As letters from Kuribayashi pointed out, they’d work maybe ten or fifteen minutes, and then they’d have to get out. Otherwise they’d collapse from heat exhaustion.

“They were going to die anyhow, and he told them, ‘Look, guys, I want you to kill ten Americans before you die.’ That was the order. And it looked like for a little while like they might be able to do that. It was the only battle in which we lost more than they did. They lost about twenty-one thousand and we had more than six thousand dead, nineteen thousand wounded.

“Prior to the landings, we had asked for ten days of bombardment, but the Navy said they couldn’t do that. We said, ‘Well, give us five.’ They couldn’t do that. So they gave us three, but the naval bombardment was what got us ashore and across the narrow neck. It saved our butt. The Navy guys were very courageous, and they came in close in gunboats, snuggled right up against the beach, firing directly into the caves on Suribachi. Each of our battalions had a destroyer in support, and the regimental combat team had a cruiser in support. The division had a battleship. There were actually two battleships, five cruisers, and nine or ten destroyers in overall support. And it was effective in the southern third of the island; it was less effective up by the Quarry to the north and on the ridgelines. Naval gunfire is a flat trajectory weapon and difficult to use in many places. About all you could use on the ridges and hollows was artillery and mortars. Artillery tubes began to wear out when Combat Team Twenty-eight started to fight in the north end of the island. We ordered new tubes, and one of the unfortunate incidents of the war was losing those tubes. They were being delivered by air from Guam, and the wind shifted with the first batch, and we sat there and watched the tubes parachute right in the water. So we had to deal with inaccurate artillery tubes.

“Many of us thought Cheney Johnson, who commanded the Second Battalion, was probably killed by our own artillery. He was blown to smithereens. I think all they found was a piece of his torso and his shoes. Eventually we got new tubes, and the artillery became more accurate. Cheney wore a combat fatigue hat. He never wore his helmet. My personal view is that Johnson tripped the detonator on a U.S. aerial bomb dud the Japanese had rigged just north of Hill 362. Captain Naylor, the F Company CO, had warned Johnson not to go into the ravine, but he did and met his demise.

“But you need a few guys like Johnson, who sort of wander around the battlefield without their helmets and get things done. They become an inspiration to the troops. That was true of Liversedge, who was our combat team commander, and of Williams, who was his exec, and Johnson.

“Suribachi was captured on the fifth day. We landed on the nineteenth of February, and the flag went up on the twenty-third. The first flag went up at ten-twenty a.m. The second and most famous one went up about two that afternoon. We didn’t pay much attention to the second one because you know, we were all busy, fighting the war, and the big impact was the first flag. You could barely see it, just a little tiny thing. Major Oscar Peatross—I was his deputy—and Williams and I went up the mountain shortly after that first flag was raised, when the second patrol was getting ready to come up.”

From the top of Suribachi, Haynes and his group got their first view across the battlefields.

“We saw the mess on the beach and what we had ahead of us. You could see the real challenge was going to come once we got past the airfields, where we had one hell of a fight. That photo of me was shot while we were taking Hill 362. We had more casualties in three days taking 362 and Nishi Ridge than we had taking Suribachi. We lost two hundred fifty men a day up here. That’s more than a rifle company a day, boom boom boom.”

[Haynes described the landscape around Hill 362 Able in an article for the Marine Corps Gazette in 1953: “Northern Iwo was a treeless wilderness of cave-studded, jagged, frequently ill-defined compartments, radiating from a central plateau toward the coastal cliffs. The terrain around Hill 362 constituted the right (west) one third of the main cross-island position. It dominated the western side of the island south to Suribachi.”]

“That was the meanest fighting because whereas we could get naval gunfire into vertical sections where all the caves were, here you couldn’t do it. We had to depend on infantry guts, just getting up to these places and then cross them.

“The battle became a slogging thing, almost a depressing proposition, because there had been all the excitement and progress: We took the mountain and put a flag up, and when we went into the line, we fought on the left flank. Progress from midway on was just tiny. Some days, if we made one hundred yards, we were really doing it. On our side we had to cross corridors, and when you do that, you get enfiladed. At Iwo it was from the back, the front, and both sides. That’s why we lost so many people in the north end, particularly in fighting for Hill 362. We attacked every goddamn morning. We’d jump off around seven-thirty or eight o’clock. Wherever Williams went he always took me. In the evenings at the end of each day it was our responsibility to make sure our lines were tied in, particularly with the Fifth Division units on our right.

“I went up to our OPs [observations posts] frequently, and I could see what we were faced with. The proposition I made to Colonel Williams and Liversedge was we should try to form a horseshoe, so we could go down these corridors instead of across and avoid the enfilades. So Colonel Liversedge said, ‘OK, get yourself an airplane and go look.’

“So I went to Airfield No. 1 and asked a pilot of a grasshopper, one of these little Piper Cubs, to fly me down the corridors and then back up the corridors from the sea. I told both colonels what I had seen made it seem right. The idea was to hold the line steady and swing the right-flank units around to positions from which we could attack down the corridors.

“Then you’re going the length of the corridor instead of across it. And when you did that, instead of going where you got fire from the flanks, like in the case of 362, where we lost a huge number of casualties by fire from the rear because these bastards had caves up here on the south side, and then they had these interlocking caves, underground tunnels, and they came out on this side and they could shoot you in the back. So if you came over the top, you not only got hit from the back and the front, but you got the sides also. There were probably fifteen or twenty of these corridors, each six hundred to seven hundred meters long. So the aim was to go up them instead of across. Then you could put machine guns and observation over on both sides, and you could shoot this way and that way, and it was a lot easier: set up interlocking fields of fire and close off the caves. And that was what we did ultimately. There’s no way you could tell for sure how many casualties we reduced, but whereas we had huge casualties initially, once we started that maneuver, the numbers dropped off.

“I had no frame of reference from past experience. Nobody did for this kind of thing. This was really the first time that any of our officers and men had been in anything like this. In fact, nobody did after that either, even though Okinawa was a tough place. Very few Japanese surrendered on Iwo. My Combat Team Twenty-eight captured a total of sixteen prisoners in the thirty-six-day campaign, and all but two or three had been wounded or were physically incapacitated from lack of food and water.”

Why were there so few? Were captured Japanese simply shot?

“We conducted an extensive indoctrination program prior to Iwo in which we made a strong point of the need to take captives. This had to be done with great care because the Japanese were very canny: They’d put hand grenades under bodies of their own people so that when you moved them, the grenades would go off; they also booby-trapped artillery shells, kind of like these guys the jihadists are doing in Iraq. So we urged the men to be very careful in how they took people. Nearly everyone we captured begged to be shot. They begged to be killed.

“During the interrogation of one prisoner, he said, ‘You know, as far as the Japanese are concerned, I’m dead.’ Which was another way of saying, ‘I can’t come out of the woodwork. I’ve got to be very careful.’ It was hard to find any POW who would talk. But I well remember an instance in which a Japanese was buried up to his neck in debris, from an artillery round, probably, and he was alive. One of our Japanese-language officers gave this guy a cigarette and then very gingerly removed the dirt from around him. He confirmed some of the order of battle information we already had.

“The most useful intelligence, after we landed, came mainly from our own OPs, our aerial observers, and from documents that we found in a couple of caves in Suribachi. So we had a pretty good idea of what the order of battle was. We also had two excellent interrogators, who had been to the Japanese-language school, and we had a third, John Lloyd, who had been raised in a missionary family on Honshu. He knew Japanese street language.

“By the time we finished 362, we were not Combat Team Twenty-eight anymore. Our leadership was gone, we had only a couple company commanders left, most of our lieutenants had been either killed or wounded, many of our NCOs had been killed or wounded, and I liked to say we walked by faith. Casualties in the companies of the Twenty-eighth were running well above fifty percent by the evening of March 1. We just believed in the guy on our right and the guy on our left, and we had been told to do it, and we were gonna do it, do it to the end.”

[Haynes has written his own account of Combat Team Twenty-eight’s ordeal, The Lions of Iwo Jima, published by Henry Holt.]

“Yates, the runner who killed the Japanese when my rifle didn’t fire, later had his leg broken by sniper fire and had to be evacuated. He had had this damn little black and white terrier, a mascot he called Tige, short for Tiger. He smuggled him aboard ship to go to Hawaii and then smuggled him aboard ship to Iwo. Yates was primarily a runner for Williams, and the night before D-day I was in the wardroom. I couldn’t sleep, and neither could Williams. He said to me, ‘What the hell are we going to do about Yates’s dog? We can’t take him ashore.’

“And I said, ‘Well, you know the Navy kids will take care of him, so we can tell Yates to leave him aboard.’ But I remember saying to Williams, ‘You know he’s not about to do that. He’ll smuggle him somehow.’ And he did. He put the dog in his knapsack and took him ashore. Later, after Yates was wounded and evacuated, we got one of the communicators to take care of Tige, and he lived through the battle. We decorated him with an Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal with one star, put it on his collar when we got back to Hawaii.

“What was the Japanese leadership like? The commander at Iwo, Tadamichi Kuribayashi, had been an attaché in the United States. He was also a cavalryman, and he wrote a song to the horse cavalry. Both he and Lieutenant Colonel Takeichi Baron Nishi, who commanded a Japanese tank unit at Iwo, at various times had indicated that the Japanese were dumb as hell to fight America. Both knew they couldn’t beat us. But nobody paid any attention to them. So Kuribayashi ultimately committed hara-kiri toward the end of March. We know this mainly from intercepted communications.

“He sent a message on the fourteenth telling the emperor that he was sorry but he didn’t think he could hold Iwo. We’re not sure of this, but we have fairly good evidence of Kuribayashi’s death from a Major Horie, who was on nearby Chichi Jima during the battle for Iwo. He thought Kuribayashi stuck himself in the gut with a knife and had his aide chop his head off.

“Nishi dug all of his tanks in and used them as pillboxes on Iwo. Between the fifteenth and the twentieth of March, he got hit in the leg and then committed seppuku. We never found his body. These are things that we found out from the very few Japanese who lived holed up in caves.

“Kuribayashi’s eldest son is still alive. His name is Taro, and he is a member of the Upper House in the Japanese Diet. Kuribayashi had two daughters, one of whom died of typhoid in Tokyo during a B-29 raid there, and the other became a movie star, believe it or not. His grandson is in the foreign service of Japan.”

What happened to the island after the battle? It provided an emergency landing strip for crippled B-29s returning from attacks on the mainland, for one thing. Haynes described another purpose.

“Iwo Jima became a critical navigation point for the atom bomb attacks on Nagasaki and Hiroshima. Colonel Paul Tibbets, who was in charge of both bombings, had Charles W. Sweeney, the pilot for the Nagasaki bombing, go to Iwo and dig a bomb transfer pit near Suribachi, down at the end of the runway. This was so that if Tibbets’s plane, the Enola Gay, had trouble, she’d be able to get back to Iwo, come over the transfer pit, and lower the bomb into the pit, so he could get another B-29, pick it up, and go finish the mission.

“Second, three B-29s followed Tibbets. One, McKnight’s Top Secret, landed at Iwo as a standby aircraft in case the Enola Gay had trouble en route. Chuck Sweeney in the Great Artiste and George Marquardt in Number 91 flew the entire mission with Tibbets from the Marianas, and they used Iwo as a navigation point. After Tibbets made the drop, they were the ones who did the photography and the radiation checks. And of course Sweeney then turned around and three days later flew the second A-bomb to Nagasaki.

“What gives the battle for Iwo Jima such lasting significance? First of all, it was the bloodiest and most difficult of any battle that the Marines fought, ever. Even though Okinawa was greater in terms of casualties, it was a battle where three Marine divisions and several Army units participated. And the Iwo battle had enormous significance nationwide and worldwide because of the photo of the flag raising taken by Joe Rosenthal. It was a huge boost to morale back in the U.S. People were getting weary of the war. The European war they were pretty sure was going to come out OK, but here was Iwo, a little tiny goddamn island, eight and half square miles. Tarawa had been a tiny island, and it had been terribly costly. Peleliu had been costly. The Marianas had been costly. Guam had been costly. The war tolerance in the U.S. was pretty low, so this was a huge boost to the morale in the U.S. The photo epitomized courage, cooperation, patriotism, working together. It had a Navy corpsman in it. You remember, there were five marines and one Navy guy.

“A second feature was this: You can’t identify the flag raisers. You can only see a little part of James Bradley’s face, hardly enough to recognize him. The others are hidden, and they could all have been unknown if Roosevelt hadn’t said you got to bring them back. We didn’t know who they were. This was not a posed picture, and it was so symbolic because of where these marines came from.

“The guy putting the flag in the ground is Harlon Block, another high school football player from Texas, who joined the Marines with all the senior members of his ball team. Bradley was a rural kid from Wisconsin. Ira Hayes was a Pima Indian from one of the poorest tribes. Strank was probably the best of all the group. He was a sergeant, an immigrant who came across as a baby with his parents from Czechoslovakia. His dad was a coal miner, and Strank became a coal miner until he joined the Marines. He was killed, of course. And Gagnon was a Canuck from New Hampshire or Vermont. He’s the one you can’t see. You can see a hand, I guess. It was a representation of America. The only thing not there is a black. We didn’t have black Marines in combat.

“We had a black DUKW company [see page 255] that was Army, and we had ammunition and depot companies, most of them black, on the shore party, and they did a lot of the digging of the graves. They were in that last fight, and Harry Martin was given a Medal of Honor. He was killed there.”

Iwo Jima is the signature battle of the Marine Corps because it epitomizes keeping going in the face of fatigue and an enemy who fought to the death. It epitomizes the Marine Corps’ esprit, which is a lot like love. It’s impalpable. You cannot touch it. You cannot exactly get your mind round it, but you certainly know it when it’s there. Marines trust one another. You have this animating spirit, this belief in the guy on your right and the guy on your left. They’ve all been through a similar kind of training, and it’s tough training done by people who have been in some pretty tight spots. You understand that these guys know their job, and they will cover you and you them. It’s a belief, too, that you can’t beat us because we’re in it until the end, and we’re in it together as Marines. You may knock a few of us off, but if you do, watch out. If you kill Marines, one thing is for sure, there will be other Marines coming along soon, and they will keep coming until they find you.*

After World War II Haynes rose to the rank of major, serving as executive officer of an infantry battalion in Korea. As a colonel he became military secretary to the commandant in 1968. After being promoted to major general, he was given command of the Second Marine Division on the East Coast and, in 1973, took command of the Third Division in the western Pacific.

“Headquarters had moved from Vietnam to Okinawa, and we did the evacuation of Phnom Penh. Later I was given command at Camp Lejeune, North Carolina, and went from there to Washington for my last tour of active duty. I retired January 1, 1977.”

Following retirement, Fred Haynes joined an aerospace firm, and for several years he was a military commentator for CBS News in New York. He is chairman emeritus of the American Friends of Turkey, which later became the American Turkish Council. He also is a member of the Council of Foreign Relations. He and his wife, Bonnie, a TV producer, have four children between them from prior marriages.

*Fred Haynes speaking in American Spartans by James A. Warren.