6

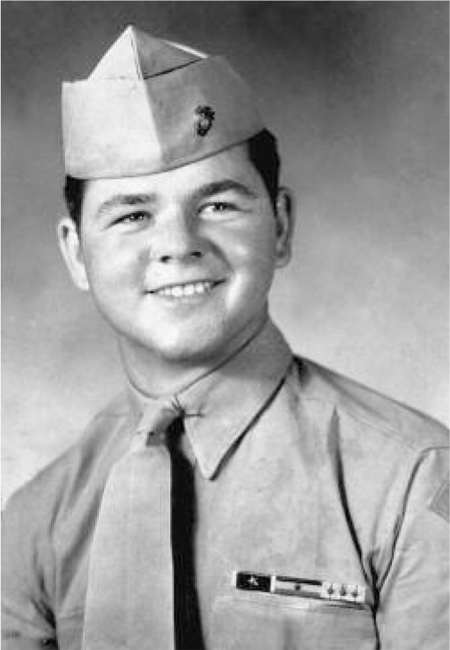

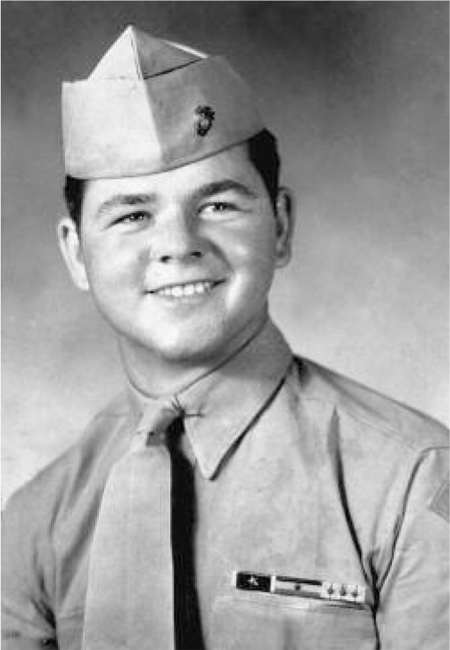

CORPORAL GLENN BUZZARD

Machine Gunner

Twenty-fourth Marines, Fourth Marine Division

Two Purple Hearts

I didn’t have to shave. I wasn’t old enough.

Standing in the yard of his Ohio home in August 2005, Glenn Buzzard holds his dress uniform in one hand and, in the other, the thirty-eight-caliber pistol his brother Erett sent him. He purchased his dress uniform when he graduated from boot camp in 1942.

The decorations on young Glenn Buzzard’s blouse include a Purple Heart with one gold star, signifying two recognitions. In the center is a presidential unit citation with a star, again indicating two citations, and an Asiatic-Pacific Campaign ribbon with three stars, signifying four battles. On the left shoulder is the Fourth Marine Division patch, the ruptured duck, an eagle in a circle, signifying combat experience.

I spoke with Glenn Buzzard several times over a period of months. We met at a few different reunions, and I visited him and his wife, Needra, at their home in Ohio. One time he told me how Pretty Boy Floyd, the notorious bank robber and killer, had been shot to death on October 22, 1934, by the authorities on the farm across the road from his father’s place in East Liverpool, Ohio, just two months before Glenn himself came there to live with his dad. “His [Floyd’s] car had run out of gas, and he walked a short distance and came up and asked this older couple for a meal. Back in them days they would feed you.” Floyd wanted a ride to Columbiana and was talking to the couple about it when the authorities “got wind of where he was at and surrounded the place,” Glenn recalled. “He went out the window and down past the corncrib and the barn, and that’s why them two buildings were all shot up. And then he got out into the field, and they finally hit him and got him down, and then, according to what I hear, they didn’t give him any sort of a chance, just kept shooting at him while he was laying there on the ground. They wasn’t going to take any chances. My dad was home, working, and he heard gunfire and a hell of a commotion. By the time he got over there they wouldn’t let nobody around, naturally, but then they brought his body right up to the edge of the road to be picked up. They drug it up there, and he was laying there on the ground, my dad said, riddled with tommy guns. He was a modern-day Robin Hood is the way it’s been put. He had killed people, no question.”

Glenn Buzzard was born in Chester, West Virginia, on December 15, 1925. His mother died in childbirth just before he turned five. There were two other boys, and his father was a bit of a hell-raiser, as Glenn put it, so “an old maid” named Nancy Lee Conkel took him home to live with her in Canonsburg, Pennsylvania, in the spring of 1931. His older brothers, Arnett and Erett, were taken in by others. “People didn’t keep track,” Glenn recalls. “Today you couldn’t get away with that, but back in them days people farmed kids out and everybody was happy. Nobody stuck their nose in it. I know it’s farfetched. The Depression was on, and Dad had to move out of his farm. Dad was a wild fella. He’d get out and get in fights. He was pretty rowdy. He had moonshine. But he never mistreated us kids.

“Nancy had a place across from my dad’s, but she just came down in the summertime. She had a big old Buick, big wooden steering wheel on it. She was just a little person; she’d sit and look out through the steering wheel. She and my dad knew each other; maybe he farmed some of her property. They was just friends. She was a businessperson, as they called her, and never had been married.

“My mother died in November when I was four, and I turned five December 15. Because he knew the authorities would be coming out in connection with her death, Dad got rid of the moonshine still he kept upstairs. He kicked out the back of the gable end of the house and dumped everything, sour mash and all, out there to the chickens and the pigs and the ducks. He had to dismantle the whole still. I don’t remember that personally, but my brother Arnett is eighty-seven this February [2007]. He’s still got a real good mind, and I went out of my way to ask him questions. He said the pigs were wallowing around drunk.

“I was with Nancy till I was thirteen, about eight years. I’d come down in summertime and stay for a week with my dad or with her relatives in Chester. I went to school in Canonsburg. She was associated with the WD Wade Company and sold women’s clothes out of the back of her car. She would go to Pittsburgh and buy the stuff wholesale. I remember she had big suitcases full of jewelry, men’s jewelry: watch fobs—those were a big seller—stickpins, sleeve garters. That’s how she made a living. She’d buy everything by the dozen and go door to door, sell one at a time. She had magazines, books, and cloth samples. Corsets was a big one back then.

“I delivered stuff for her after school, and on weekends I’d run clear across town. She kept her table completely set for eight people at all times, knives and forks and everything laying just so, and what she done she lay back one corner of it and we eat there every day. On Sunday I had to go to church. I wasn’t allowed out to play because it was the Sabbath. She was strict about that.

“Long dresses was in, naturally, and she went up a stepladder to get up into the cupboard—I think it was my birthday in December—and she got her heel in her dress and pulled herself off that ladder. She went to the hospital, probably there for a couple weeks. I was home alone going to school.

“Canonsburg wasn’t a big town. Everybody knew everybody. You didn’t lock your doors or nothing. There was only two police. Attis was the chief, and Haney was his assistant. He was a little short fella and wore those knicker pants with big black leather boots, and he rode that motorcycle all over town. Down below Canonsburg was a children’s home, Morganza.

“Haney come out on his motorcycle and said, ‘You know they’re coming to get you in the morning, to take you to Morganza. Don’t you have a father somewhere?’ I said, ‘Yeah. Down in Chester, West Virginia.’ So he took me and my dog Spanky back down to the station and put me to bed up on the fire truck on them hoses, and then he called Chester and got Doc Lyons, the chief of police in Chester. It was the dead of winter, and Doc Lyons walked up Middle Run Road to Cunningham’s house. He knew Cunningham and my dad knew each other. My dad was at work in Weirton, West Virginia, in the mill, but Leonard Cunningham was a good friend of my brother Junior, and he says, ‘I’ll go get him. I know where it is.’ So he did, in the middle of the night. He brought me down there, and I went right with my dad. It sounds complicated, but that was how things played out.

“I was in eighth grade, and my dad had remarried and had three more children, and me and my stepbrother would ride this red horse, a gelding named Charley, to Clarkson school and then tie its head up so it couldn’t bend down to eat and let it loose. It would go back to the farm, and Dad would work it all day. Then we’d walk home, four or five miles, after school.

“I quit school at fifteen and went to work in a pottery, carrying molds. I was running around, and I got my first car, a Model A Ford truck. It would pull Logan’s hill in high gear. That’s how you could tell if it was a good vehicle. I didn’t have to double clutch to get over neither. I gave one hundred fifty dollars for it.

“Everybody older than me was going to the service, and I was partying and getting in at two o’clock and having to go to work at six, and I got tired of that. So one day I just went to Pittsburgh and enlisted. There was a local football player who joined the Marines and got shot up on Guadalcanal. I suppose that had some influence on my decision to join the Marines. Anyway, I took my old Ford truck and went to Pittsburgh, found the post office building, enlisted on Monday, and they said come back up on Tuesday with my birth certificate and paper signed by my dad and the chief of police, and you’ll go right straight to Parris Island. It was August of ’42. My age, which was sixteen, never come up. Monday they gave me some physical and stuff and everything seemed be OK. Only thing was, I was humiliated to death because I never wore undershorts.

“The only time my age came into play, I was in boot camp on Parris Island, and the drill instructor, his room was right at the end of our big long wooden barracks, he called me into his room. I’m sure he wasn’t too polite about it, but anyway, he just said, ‘Do you want to get out of the Marine Corps?’ I said, ‘No.’ He said, ‘OK, go back to your bunk.’ I suppose they had to ask that question to keep it legal, because somebody had found it out.

“I started boot camp in August, took the train to Yemassee. We got off there, got in them trucks. It was dark, like they always say, dead of night. You had to stand up on the trucks. Once they got you in, it was so crowded you didn’t need worry about falling over. Boot camp didn’t bother me much. I didn’t have to shave. I wasn’t old enough. I was underage, but also, having the farm background, I was probably in better shape than most of them there. I was six foot, and I weighed one hundred forty-four pounds. I probably knew more for my age than most kids that had a mother and father did. We had a lot of boys from New York and West Virginia. They didn’t get along at all. There was always a lot of trouble in our platoon. Consequently, when two guys got into a fuss, we all had to pay for it.

“When we got out of boot camp, we went straight to New River. We had rifles at Parris Island, but we did not get to fire them until we got to New River at Hadnot Point, all part of Camp Lejeune now. We trained with Springfields at Parris Island, but when we went to the range they gave us M1s. We lived in tents.

“We trained and trained, and they built us up, and when they had enough people, they called us the First Separate Battalion. Mike Mervosh was in it too. We got six days’ furlough, and when we came back, they put us on a troop train to Camp Pendleton. Then they brought other outfits in, and in the spring of ’43 we became the Fourth Marine Division.

“When they had enough battalions, they’d make a regiment and then it takes three regiments to make a division. The Twenty-third, Twenty-fourth, and Twenty-fifth regiments became the Fourth Marine Division. [A platoon contained about 45 men, a company had 250, a battalion contained 1,100, and a regiment accounted for 3,300, or three battalions. There were 20,000 men in a division.] Plus there were headquarters companies, artillery, mortars. We were in machine guns. We didn’t even train with the riflemen until we went on maneuvers; then we fit in because that was the way you were going to fight.

“That’s how I got to know people in A Company, B Company, and C Company. We had three platoons in D Company, which was a weapons company. They would take the First Platoon in D Company, put it with A Company, machine guns. Second Platoon, B Company. I was in the Third Platoon, and we’d go to C Company. Next time we went out they’d maybe put us in a different company. That’s how I got to know those guys. But after Roi-Namur they got so low on officers they couldn’t shift us around. So they changed that. Put First Platoon in A Company and so on. I was in C Company from then on.

“You had four squads in a platoon, two sections, a gun in each squad, so that’s four heavy water-cooled machine guns and four light machine guns. You used the light air-cooled machine gun in the daytime; then at night you set up your air- and your water-cooled machine gun and you’d cross your fire, set up interlocking fields of fire in a solid wall right down the line. The heavies had a big water case. We trained with them a lot. We had carts to pull them on. The gun weighed ninety-one pounds, and we used it strictly at night. It was always right behind you on a jeep or something. We carried the air-cooled guns and had Browning automatic rifles, the next best firepower. You needed firepower. That was the name of the game.

“The BAR was lighter than our light machine gun, but it was a damn good weapon. It was part of the rifle platoon. They let us fire the machine gun from the hip. It would work, and I did it. You had to have an asbestos glove which they gave you. We’d tape that asbestos glove right on that barrel, and then we wouldn’t lose it. Then you’d put an ammunition belt around your neck and tie it on to that gun. The worst thing was you couldn’t put a whole belt through it because you couldn’t control the belt feeding into it, so you cut the belts, which were canvas. The fifty calibers had metal belts. We cut it to maybe thirty shots. You only fired when you really needed it.

“I was a machine gunner all the way through. I never carried anything else. We had side weapons. They tried shotguns, and they tried carbines. The shotgun was a good weapon because it scattered, especially in jungle, but was hard to keep clean, and the shells were paper, so when they’d get wet, they’d swell up and wouldn’t go in the chamber. When I became a machine gunner, I needed a sidearm. They came out with forty-fives, but they didn’t have enough, so they give them to the squad leaders. Junior, my brother Erett, sent me a thirty-eight through the mail along with a Bible. The thirty-eight had no grips. It was up in the attic, just layin’ up there, a six-shot Smith and Wesson. I knew it was there, and I asked him for it. I was on liberty somewhere, and I bought an old black holster for it. I had to get special permission to carry it. You peart near had to be in combat because I couldn’t wear it with my dress uniform any way, shape, or form. I must have bought the ammo for it in Hawaii. They were lead bullets, which would splatter, which was good. It didn’t have no handle grips, and I made a pair of wooden ones and taped them on. I carried it through all my campaigns.

“The first time I used it was in Saipan, on a banzai attack when a Japanese tripped over my machine gun in the dark. Needless to say, somebody killed him. I don’t know whether I did or not. I fired at him with that thirty-eight. I know I had it going at him because it was close quarters. I couldn’t get the machine gun on him, but whether I or somebody else did it, I kinda thought maybe I did it, but then it’s nothing to brag about, taking a man’s life. They was there just like we were, probably didn’t know any more than we did. Anyway, that’s life, that’s the way wars are. People that know everything ain’t in the war. They’re sittin’ back somewhere.

“I was wounded later that night in a mortar attack. Somebody took the thirty-eight off me because I had to go back to the beach next day on an ammunition truck to get patched up. It was in my back and shoulder blade area, but it was pretty well cauterized. Adrian DeWitt from New York somewhere pulled that shrapnel out. It was long, about an eight-inch sliver, and it was spent to a good degree. Otherwise it would have took my shoulder off. Another thing saved me on that one was my poncho. It was all tore up, so it took a lot of the shrapnel down in the kidney area. But I did get my thirty-eight back.

“For the trip to Iwo we boarded ship at Maui, had maneuvers at one of the other islands, then went to sea again. Then we went to Guam but didn’t get off. Finally they told us where we were going.

“It was pretty devastating when we landed that morning, February 19, 1945. My first thought was: Why the hell didn’t they know the island was this way, because of the sand and stuff like that? We wasn’t just fighting the Japanese; we was fighting the elements, the island itself, the make of the island, worse than anything else. The devastation was terrible, bodies everywhere. They put nine thousand marines ashore the first day. You can figure it out yourself, nine thousand guys, and they weren’t more than three hundred feet off the beach. They couldn’t get far. It was devastating, just carnage everywhere.

“Not knowing about that sand was a big failure by our intelligence people. The other was they didn’t realize the Japanese people could go underground that far. The effect of the bombing was almost nil. We thought it was doing a hell of a job, wiping them out every time we dropped a bomb, but we weren’t.

“We landed up at the boat basin, as far away from Suribachi as you could get, in about the third wave. Everything didn’t go according to Hoyle. They were trying to get nine thousand people on there in eight or ten hours. I’m not trying to take any glory from any wave. I was not in the first, but when I got there, the first wave was laying right there, waiting for us. Bodies everywhere; equipment couldn’t move. The main thing was to get out of that boat and get the hell off that beach, three hundred feet in if you could. You’re still right out in the open. It wasn’t any safer, with every firing mechanism pointed at that beach. Nine thousand people they said put ashore the first day. That’s a hell of a lot of people; it was elbow to elbow.”

Why wasn’t the landing force annihilated?

“Just sheer determination, I guess, or maybe they didn’t have the ammunition to expend on a full-blown assault. Maybe they were conserving ammo, but I don’t see any reason why they couldn’t have blowed us clear off that beach. Only thing is we just overwhelmed them, I suppose, bodily. It boiled right down to the individual person. The company commander wasn’t telling him what to do; the first sergeant wasn’t telling him what to do. If Kuribayashi’d had more weapons than we had, we probably wouldn’t have made it. But say eight or ten of you came to a hole in the ground and it was a pillbox, and if you was getting trouble with it, you congregated on it and took it out. You couldn’t call for tanks, couldn’t call for rockets. It was just sheer determination, small-arms initiative.

“The Quarry had guns sticking out of it, and the friendly fire damage was about the worst I ever seen. They were trying to get at them guns and they’d call in an air strike, and our kids would just roll dead off them hills because the planes hit short. We had frontline panels, but things got mixed up, you know what I mean? It was right out in the open, just like a theater, and we was off to the left and a little bit inland, and we could look right around. When we first went in, the Japanese guns were right above us, but they were six-inch guns, not for use on us but mostly to shoot the boats. They had plenty of other stuff. They didn’t even have to point a gun. All they had to do was pull the trigger because it was all zeroed in. So the Japanese’d send up some guys, and they’d go pull triggers, and then the guys’d disappear. Then they’d send up some more because they had the people there, and it was all under cover. Most of the guns were in caves, and they slide right up to the opening, fire, then slide back. They’d put camouflage over them, brush, netting, whatever they had.

“The strafing planes hit the marines. A frontline panel is an orange plastic sheet you can roll up. One guy in every squad had to have one, and when they’d call to put out the frontline panel, an air strike was coming in, it was up to that one guy to run out there as far as he could beyond the front line out in no-man’s-land. It was dangerous as hell to try to roll that thing out. It worked pretty good from up in the air. You could see that thing, but short firing was bound to happen especially from the face of that cliff because they’d come in off the water.

“When an air strike wasn’t happening, the company commanders would be sending guys like Domenick Tutalo with flamethrowers up there to try to get into that cave and seal it off. Machine guns would be firing right into the opening, trying to keep them down till our guys worked up there, and then, all at once, an air strike would come in. They were bound to get hurt. I think that was the worst I ever saw of something like that. First, second day. Third day I’d say we’d probably taken those guns out of there, and we were past that. Starting to make the swing up the island. We didn’t have to go inland too far before we started to swing north.

“The Fourth and Fifth were abreast, and the object was to move right across that short pork chop thing and secure that part and then swing to the right and to the left, that’d be Fifth Division on Suribachi, and then we went to the right, and that’s where we spread out and needed some people, and that’s when we brought in a few of the Third Marine Division.

“You didn’t see too many Japs. Once in a while they’d run from one cave to another. You more or less seen their fire. You could see dust coming. As soon as we’d see that, we’d zone right in, and when we got up there, they’d be layin’ there.

“The terrain got rougher and rougher because of the catacombs and stuff where the water had washed in amongst it over the years. Some places you could step over a crack and you’d see a big gap deep down in there. Or you’d go around the corner and they’d be standing right there face-to-face. Whoever shot first was the winner. I saw one marine shoot another marine bone dead right in my squad because he went around this way and the other went around that way and, it was just like I said, you don’t have a split second. You just pull the trigger. Shoot first. Whoever does, they’re one’s going to win. We had to take the guy that shot the other marine, take him clear out because he just went berserk.

“The first day of March I was wounded and evacuated out to a hospital ship. It was shrapnel like I’d got in Saipan. I was taken aboard ship and cleaned up. They picked that stuff out of me. It was mostly like buckshot. One thing about shrapnel: If it hits you the right way and it’s a little bit on the spent side, not with full force, it’ll burn you, and when it burns you, it cauterizes the wound. That’s what it did to me on Saipan because Adrian DeWitt pulled it out of my back and they put some sulfa powder on it and I never had a minute’s trouble with it. But the corpsman would bandage it every day for me, check it, and I stayed in action.

“My big problem on Iwo came from a concussion, not that shrapnel. I was in a big hole with ten or twelve other guys, and a shell came right in there. Near as I can remember, I was the only one came out of there alive. We were in reserve. They kept two platoons on the line, and C Company just happened to be in there getting a rest. Give you a little chance to do what you wanted, sit down and cry, or smoke, whatever.

“We were in there grouped up. You didn’t group up because it was a bad thing to do, but we did. Otherwise there wouldn’t have been as many killed by one shell. One hand grenade’ll get you all, if you don’t stay spread out. Otis Boxx was my gunner at the time. As people get bumped off, people move up in command. I had moved up to squad leader, and I had to give up the gun for a few weeks. So Otis Boxx from Florida was the gunner. The only thing I really remember is that all that was left of his head was his lower jaw. It was just settin’ there. Never moved. Just settin’ there.

“I was shocked, no question about it. I come up out of the hole, and somebody grabbed me, and I was just blood everywhere. They thought I was hit worse than I was, but they started getting my dungarees off me and seen that I wasn’t really hurt, but my mind was gone.

“I couldn’t hear. I remember giving my thirty-eight away to Elmer Neff. They took me back to the beach and took me out to the big boat, and first thing I remember is a corpsman waking me up. Or I came to, apparently. I was talking with him, and I said, ‘Where’s my clothes?’ He said, ‘We’ll give you clean stuff.’ I said, ‘Well, get ’em for me. I’d like to get some clothes on.’ So I did. Then daylight came, and they were bringing casualties in. They had a stairway up the side of the ship to bring casualties up. They couldn’t bring them up the cargo net, but there was a cargo net down there, and I clumb down that cargo net and got in the front of that boat and went ashore. Nobody asked any questions.”

Why did he go back?

“I have no idea. I have no idea. They’d dug out shrapnel, give me sulfa, and I had a hell of a headache. My vision and my hearing were bad. When that shell hit, I was out on my feet. A lot of people were killed that way, by concussion. It would just roll them along the ground like a ball. They was dead. Everything confined in that little shell goes out when it explodes, so therefore you go with it.

“I got my thirty-eight back. Elmer Neff had got killed, and somebody picked it up. A day or so later just out of the clear blue sky somebody walked up to me and said, ‘Hey, I got that thirty-eight off Elmer when he got hit, so here it is.’ I walked right back up there and found out where C Company was, I kept asking, ‘Where’s C Company?’ and I finally found where they were, and I went right back to work.

“I’m not sure who was company commander at that time. It might have been Mike Mervosh. I just don’t know who had got killed and evacuated in the line of officers. Mike could very well have been my company commander at that time. We knew each other, hell, yes. We met in New River. He was in First Separate Battalion. We weren’t in the same squad, but we were all in C Company. You’d get to know maybe fifty guys. Mike was my section leader at first.

“He became company commander on Iwo Jima. A company commander could have been a major. Mike didn’t become a major. You just became the company commander even if you were a buck-ass sergeant because there was nobody else to do it. Then, when you went back to Maui, they’d call you out on the parade deck and have a pretty nice ceremony out of it; they’d call everybody out in formation and either give them their promotion or their Purple Heart or whatever. You didn’t know you was getting a Purple Heart because the only thing that gave you a Purple Heart them days was your medical records. The first sergeant wrote in the book you were treated, and you were in line even though your wounds were not serious. They had what they called the walking wounded. And that’s the way you were put: WW. And there was WE, wounded and evacuated. So first I was WE or walking-evacuated, and then I was WW or walking wounded. When I come back off the ship, he put me in as WW.

“Day to day you’d have riflemen go out in front. The number one guy would go so far and keep track of the guy on his left and the guy on his right. There wasn’t no talking going on. It seemed like we had to put bait out there to draw their fire. Then we’d find out where it was coming from and focus on that. If their fire was severe enough and determined enough, we had to call for more support. Rockets were a great thing. The Dodge power wagon had these things mounted on them. They’d bring up seven or eight in a bank, and there was probably fifty rockets on each of ’em in a canister and they’d go chu chu chu, a hell of a noise, and boy, they just blanketed the target area. They didn’t have to be too accurate. And grenades were good. You could damn near throw a grenade ten feet, and it would go down a crevice and you’d hear somebody scream or moan or groan or something. You knew somebody was in there. Grenades were a good thing, and we used a lot of them.

“If your skirmishers found a cave, it would take a considerable amount of time to work your way up to its mouth. The machine gunner would cover the front of it so you could get your flamethrower close enough to shoot flame in. As long as you’re firing into that cave, you’re keeping their heads down, allowing the flamethrower time to get close, and then the demolition man had to be right there within arm’s reach to throw the damn satchel charge. Most of them are still in those caves. We killed more accidentally than we did on purpose, put it that way. Sure we was trying to kill ’em all, but we didn’t realize when we sealed a cave how many we killed. We killed thousands.

“Some days we didn’t move. One side couldn’t move past the other. We had to keep order, especially when the island started getting smaller as we moved up. They’d spell us off, give us a little rest. I can’t remember sleeping, but I’m sure I did, and I don’t remember ever going to the bathroom. I’m sure I did. There’s things you don’t remember. I think you’re programmed, and you’re just like a zombie, but you have to pay attention to your surroundings at the same time. Then you live longer. I think sometimes guys would just forget where they were at, and bingo, they were gone.

“Believe it or not, as a person on the front line you had it better than them in the rear. You were relaxed, you might say, because you knew where the enemy was. They were right in front of us. But if you went into reserve and were trying to crap out like we were in that hole, there’s enemies all around you all the time. They can lob a shell at you or get behind you through tunnels going everywhere. You didn’t know where the hell they were. That was one small advantage of being on the front line: We knew where they were.

“I was nineteen on Iwo. I came back from wounded and evacuated to walking wounded and finished out the campaign with no more trouble than an infected fingernail.”

Glenn married his wife, Needra, in 1949, and they live today in Hubbard, Ohio. They have five children. Glenn farmed most of his life. Did his survival of the battle of Iwo Jima affect the way he lived afterward?

“I don’t know. I always tried to do the right thing. I didn’t get in too much trouble when I was a kid. I never drank to any extent. Never ran around much. That’s why I went to farming. That was a solitary life. I come home from the service, and I broke three vertebrae in my neck falling off a load of hay. That could have killed me right there. I got hurt worse falling off a load of hay than I did in four campaigns in the Pacific. I had to wear a brace eighteen months. I was seventy-nine years old, last year, I’m eighty now, and I fell down eight steps backwards there in the cellar. Could have broke my neck or hit my head on that cement.”

Why did he survive the battle?

“When I stop to think about it, I have no idea. I’m a Christian. I believe in God. I believe in the hereafter. But why me? I was no better or no worse than Cooksey or Elmer Neff or Bowman or any of those guys. But yet they took it, you know what I mean? They’re gone. Why, I don’t know. I can’t answer it. I didn’t do anything any better than they did. I wasn’t a better scholar, I wasn’t a better . . . anything. They say every hair of your head is numbered. Well, the fellow who’s got that kind of account is in charge, and if he’s in charge, then maybe he can answer that question. I don’t think God created man to do this to each other, although men have been doing it ever since Christ walked the face of the earth. Otherwise I have no idea. I cannot answer it.”