13

WARRANT OFFICER NORMAN HATCH

Photo Officer, Fifth Marine Division

[T]he brave ones were shooting the enemy; the crazy ones were shooting film.

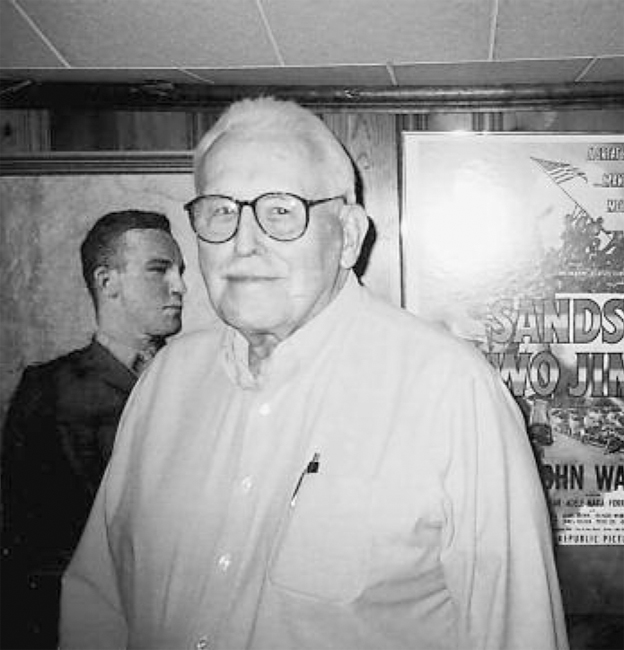

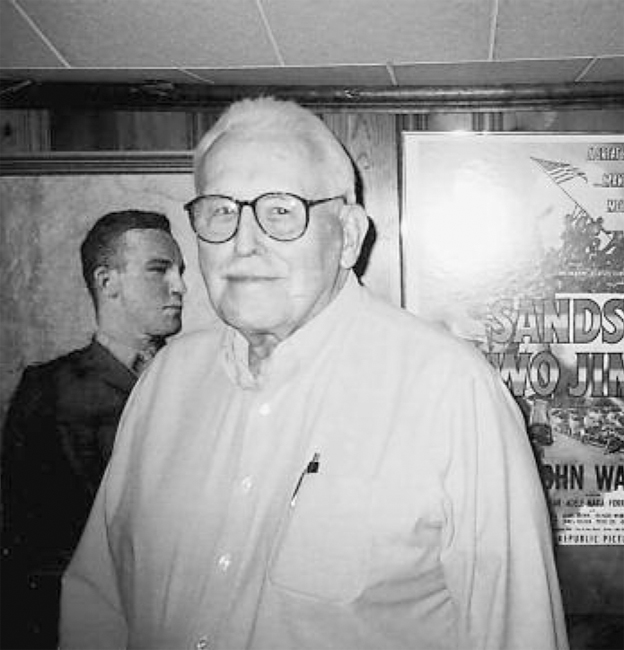

Norman Hatch, eighty-seven, in the study of his Alexandria, Virginia, home in March 2007, in front of a poster for the movie Sands of Iwo Jima with John Wayne. Behind and to his right is a colored chalk portrait of the twenty-three-year-old Hatch, then a tech sergeant, in 1942, after he returned to Boston from Tarawa. It was commissioned by an uncle.

A cassette tape of “Pennsylvania 6-5000,” a tune made popular during the war by Glenn Miller, began playing in Norman Hatch’s car as he started it up. He was driving me to the Metro station in Alexandria, Virginia, so I could catch the subway to my train at Union Station in Washington, D.C., in mid-March 2007. We had just spent nearly three hours in his basement office, a long railroad car of a room filled with memorabilia and files. His backyard contained several very large boxwood shrubs, which he said had been very small when he planted them after he and his wife, Lois, moved into the house in 1951. On the way to the Metro, he said something about how you just have to take chances in life and make things come to you, even if you do fail now and then.

Perhaps not many people know the Marine Corps won an Oscar, but in 1944 it was awarded an Academy Award for the best short documentary of 1944, With the Marines at Tarawa. One of ten men assigned to film the bloody invasion, which took the lives of one thousand marines and forty-seven hundred Japanese, was Norman Hatch, who is credited as the cinematographer. Hatch also landed on Iwo Jima on D-day, February 19, two years later and stayed there eighteen days until he left for Washington to play a crucial role in sorting out for the commandant of the Marine Corps charges that Joe Rosenthal’s photograph on Suribachi was faked.

The invasion of Tarawa took place November 20, 1943.

“I went in practically with the first wave. I was the only cameraman to get on the beach for the first day and half. It was not the fault of the other cameramen. After the first three waves of amphibious tractors hit the beach, all hell broke loose. It wasn’t just Kuribayashi on Iwo who did this. The Japanese always waited for you to get on the beach. That was their philosophy: Let ’em get on the beach, and then annihilate them.

“I was sitting on the engine hatch of a Higgins boat with Major Jim Crowe, the commander of the Second Battalion, Eighth Marines, and he saw he was losing his beachhead there at Tarawa. He was not due to come in until later. His exec was on the beach with the first waves, but they were losing the beachfront because a Japanese guy in a tank turret buried in the sand was firing a machine gun at the amtracs. They were like tin; they didn’t have any armor, and those thirty-caliber and fifty-caliber rounds would go right through them. The drivers were getting scared and pinching in away from the gun, and Major Crowe said, ‘Jesus Christ, I’m losing my beachhead. Coxswain, put this goddamn boat in right now!’

“So we were the only boat to hit the beach at that particular time. We got in and walked ashore with no problem. A couple guys got hit and dropped in the water. My assistant, Obie Newcomb, and I are lugging black-and-white camera gear on our shoulders, and we get onto the beach, and then the fire opens up. We could lie there dug in and watch a landing craft come in, drop the ramp, and then a shell would land right on the ramp.

“The Japanese knew where the reef was, and they knew where the boats would have to stop, and they had it all zeroed in. After they blasted a half a dozen boats, the guys on the beach radioed out to the ship and said, ‘Jesus, don’t send any more until we figure this thing out.’ I doubt we had six hundred or seven hundred men on the beach at that stage of the game.

“Anyway, all the rest of the Higgins boats, which had been loaded up at nine o’clock in the morning, were held off overnight, so everybody had to spend the night in those things getting seasick and dashed with spray. And there I am on the beach. I don’t know that these guys are all afloat, and I’m shooting the war as it’s happening pretty much in front of me.

“It winds up that I’ve got the only real combat footage of the fight because, when they come in about ten o’clock the next morning, there’s some fighting to be done but it’s mostly wrap-up stuff. The first nine hundred guys who got ashore did most of the action, and I filmed it in black and white. Why is the movie in sixteen-millimeter color? The kids that we trained shot color, a lot of the boat stuff, island shots, and planes dropping bombs, but when you get to the combat, it’s my thirty-five-millimeter black and white that you see. We tinted it so there wouldn’t be such a sharp contrast.

“I was able to catch the only shot, not just in the Pacific but the European war, that had both the enemy and our guys in the same frame of footage. I’d attended a briefing on Tarawa with Major Crowe and with the battalion exec, Major Bill Chamberlain, who said to me, ‘We’re going to take that big blockhouse up there. Do you want to come and cover it?’ Well, you know, a staff sergeant doesn’t argue with a superior, so I said sure. We had been sitting there in his CP, his command post, which was a big shell hole, and he’s got his senior NCOs and a couple of officers, and they plan the attack. What they’re going to do is go over the top of the blockhouse and do some damage to the air vents, drop grenades down the smoke pipes, and it’s going to happen at nine o’clock. It was just like a World War One movie, with everybody synchronizing their watches.

“All the people went back to their command units, and Chamberlain looks at me and says, ‘Are you ready?’ I says, ‘Yup.’ He gets up and yells, ‘Follow me!’ He waves his hand, and the two of us run up, climb onto the top of this thing and get all the way across and look down the other side, and there’s a dozen Japanese looking up at us, wondering what the hell we’re doing on top of their blockhouse.

“We turn around, and there’s nobody in sight. We’re the only two people on top of the world entirely. And I looked at the major. He didn’t have a weapon. I said, ‘Where the hell is your rifle?’ He said, ‘I gave it to somebody that lost his coming in.’ Where was his pistol? He lost it. I had one, but it was in back of me behind all the camera gear. And I said, ‘I think we better get the hell out of here.’ He agreed. We ran back and down off the side. He held another meeting, with a little ass chewing, and then we started to take the place. I was standing at the foot of it at that point in time, filming some stuff, and somebody yells. ‘Here come the Japs!’ So I just stood in position, moved over, and that’s when I got the shot. I was within thirty or forty feet of the enemy.

“I had a marine in the foreground, pretty much in the middle, with a machine gun, while the Japanese can be seen running across from right to left in the background. When I got back to Pearl Harbor, I sent a telegram to my wife saying I think I got a shot of both of our forces fighting and, if I did, it’s a lucky shot. It turned out that way. Andy Warhol said everybody should have his fifteen minutes of fame. Well, I got fifteen seconds of fame. That’s about the length of time it took, sixteen seconds, to go through the camera. Later people asked me how I could walk through a battle like that, taking pictures as I went, and that was when I said the brave ones were shooting the enemy; the crazy ones were shooting film. You have to remember the island of Tarawa is only about one-third the size of Central Park in midtown Manhattan. Within seventy-six hours, over forty-seven hundred Japanese and one thousand marines were killed. We only took seventeen Japanese prisoners.”

The color film went to Washington, where it was put together by Warner Brothers’ Office of War Information. Hatch’s black-and-white went to San Francisco and eventually wound up in newsreels that were shown in movie theaters, which is how Hatch’s name ended up on marquees. “Of course, being a dumb photographer, I never took a picture of it,” he recalled. Hatch eventually worked with the director Frank Capra to combine Hatch’s three thousand feet of black-and-white with the color footage to make a training film, Army-Navy Screen Magazine No. 21, to be shown to troops all over the world.

“Tarawa had hit the press in a heavy way with all those casualties occurring in such a short space of time. It was also the first time in the history of the world that anybody had assaulted a heavily fortified beachhead from the sea and succeeded. There’s a rumor—I can’t validate it, but it’s a hell of a good story—that Churchill was having trouble with Eisenhower and his own staff about the landings they were planning on the French coast. He couldn’t get them to agree that it should be done. He was watching what happened at Tarawa, and after he saw we had done it, he came to both commands, Eisenhower and the Brits, and said if they can do it, we can do it. Did that happen? I don’t know, but it’s a hell of a good story.

“I was born March 2, 1921, in Gloucester, Massachusetts. I enlisted July 7, 1939. My father had told me I should join the Navy because it could teach me a vocation, and I signed up, but they kept putting me off. They were only accepting twelve or fifteen a month from all of New England. In June of ’39 I walked in again and said, ‘When are you going to take me?’ I’d been doing odd jobs to earn a little money. I bought a Ford dump truck for seventy-five bucks with another guy, and we were hauling loam all over the city of Boston. The Navy rep told me it would be another three to five months, so on the way out I went by the Marine Corps office, walked in on a whim, and said to the sergeant, ‘If I wanted to join the Marine Corps, how long would it be before you took me?’ He said, ‘Do you want to leave Friday or two weeks from Friday?’

“I left on the seventh of July 1939. I was eighteen. When we got off the train at Yemassee, we were met by a sergeant who picked us up and took us by gig, by boat, from Beaufort to Parris Island. My senior drill instructor was a sergeant named Johnny Watkins. He wasn’t cruel, but he had his own ways. He carried the steel shaft of a golf club, which he would use to whap you on the back if you didn’t do things just right. In the early stages of training, if you didn’t do a facing maneuver properly, while marching, he would likely run at you and jump and hit you in the middle of the back with his elbows and his knees. You’d have a rifle, you’d go flying, and you might take three guys with you. And he’d say, ‘Now will you do it correctly?’ He was nimble. He was a little guy too. There was a kid, a little Jewish boy, who couldn’t get anything right. Drilling to him was just anathema, and so Watkins had him pushing a peanut with his nose on the sidewalk all the way around the barracks.

“One time Watkins didn’t like the way we were drilling, so he had us go behind the barracks, stack our rifles, then march out into the bay. It was all mud, just icky, gooey mud, and you’d get it up to about waist high, and you’d begin to founder. You couldn’t stand up straight. Some of the kids were getting scared because they really couldn’t swim that well. Finally we turned around and walked in and took showers with all our clothes on.

“Another day I was corporal of the barracks guard for the evening, and Watkins came in and said, ‘Will you mail this letter for me tomorrow?’ I saw it was addressed to Mrs. Johnny Watkins, such and such, Shanghai, China. But Johnny also had a wife over in Beaufort. That’s Old Corps for you. They could get away with things like that. There would be girls coming on the base to clean various offices, and when they passed you, they would say very quietly, so the DI couldn’t hear them, ‘Ah’m available for twenty-five cents; Ah’m available for twenty-five cents.’ They knew all these guys would be horny anyway, and they were just trying to get some guys to slip out, which was damn near impossible. Parris Island was something else in those days.

“Boot camp ended in September, and I was scheduled to go to sea school in Norfolk, which meant I’d be trained in how to react aboard a ship and wear blues and look pretty all day long. But coming from Gloucester, I’d spent a lot of time aboard ship, and I knew what shipboard life was like, and I thought: Hell, I don’t want to get sent into that. I didn’t think I could plan my future very well that way.

“While I was in boot camp, they told us to religiously read the bulletin board every day because it would tell you what your commander was doing and what the Marine Corps was doing. I followed this advice and saw an opening for an English instructor at the Marine Corps Institute at Eighth and I in Washington, D.C. I applied and forgot about it, and two days before I was supposed to ship out for Norfolk, Johnny Watkins comes up to me with a piece of paper and says, ‘God damn it, Hatch, what have you been doing? This says you’re going to teach English. What the hell kind of job is that for a marine?’ ”

Norman Hatch then found himself in a succession of jobs in the Marine Corps, from English teacher to an assistant editor at Leatherneck to public affairs, at which time he got to know the radio personality Arthur Godfrey, and finally, on October 1, 1941, to a class in photojournalism in New York City, with an emphasis on motion pictures and still photography. His film career began with another trip to the bulletin board, but it took three tries. Nothing came of these three trips. “Everything sort of happened because I either slept next to somebody or knew somebody,” he said. He was lucky enough to meet an important person. In this case it was the director Louis de Rochemont, who got him into the class. The idea was to learn how to tell a story with a camera and not just settle for the “grip and grin.”

“Even back in high school I’d liked photography. To get our so-called degree, in New York, we had to take one roll of film out into the city and come back with a complete story done in one roll, which ran through the camera at ninety feet a minute and there was only one hundred feet in there. I went out to one of these concrete chess boards in Manhattan where a lot of old men sat and played. That was my story. You had to learn to think out ahead what you were going to do.

“From there I went to Quantico, where we were doing training films, and all of a sudden two of us were ordered to the Second Marine Division. I was promoted to corporal, and we were supposed to be on the train to California Saturday night. I came up to Washington and told my girlfriend, Lois, I was getting ready to go, so we decided to get married that Saturday morning, September 19, 1942. Some cousins drove us down so she could say good-bye to me at the train. I called Johnny Ercole and said, ‘Pack everything. I’m not coming back to the barracks.’

“We were at Camp Elliott while the Second Division completed its forming, and then we sailed for New Zealand in late September. We were there eleven months and then landed at Tarawa November 20, 1943. The director John Ford had won an Academy Award in 1942 and again in 1943, for his filming of the battle of Midway, and we used to say that when we got to the front, we were going to make a film and get an Academy Award, just like Ford.

“After the filming at Tarawa and my return to the States and the war loan drive, I wound up as a photo officer with the Fifth Division on the big island of Hawaii the summer of 1944. I had insisted that we forget the thirty-five-millimeter black-and-white camera and go to the sixteen-millimeter color. It was a lot easier to carry, and the success of the Tarawa film proved its worth. So we were the first ones in the services to go completely all color. We were on the Parker ranch, one of the largest in the world, training for Iwo even though we didn’t know it. I made frequent trips back and forth to Oahu for staff meetings and got to know Herb Schlosberg, the photo officer for the Fourth Division, and he and I became very good friends. I had been promoted to warrant officer by then, the highest rank you can reach as an enlisted man.”

Bill Genaust, who shot the motion-picture film of the second flag raising, joined Hatch’s group in Hawaii.

“Genaust was one of the supernumeraries I got in the pool from Cincpac. We knew action was coming, and I had sent a request to the Marine Pacific headquarters at Pearl for more photographers and motion-picture cameramen for the next action. We ended up with probably ninety cameramen on the beach at Iwo, thirty for each division. Genaust had been wounded on Saipan and had come back on active duty. He didn’t want to return to the States, so he was assigned to me when I requested more people. I wrote up the order of photographers prior to taking off from Hilo. We sent him up Suribachi even though nobody knew for sure if there was even going to be a second flag raising.

“I went ashore on Iwo Jima right after the first wave. Once I knew the philosophy of the Japanese, I promised myself I’d always go in the first wave, I wanted to get on the beach and dig in before things hit the fan, and sure enough, that’s what happened. They let ’em get on the beach and gave them hell after that.

“I was near Suribachi when we hit the beach. I had been briefed by the colonel as to where they were going to set up once they got ashore, and it was right near the tail end of Motoyama No. 1. I had Obadiah Newcomb, the still man who had been with me on Tarawa, as my assistant photo officer now. I said, ‘Obie, we got to get up there by Motoyama No. 1. I don’t know how we’re going to make it.’ We had the broad expanse of Iwo in front of us. We’d gotten up over the hump, and I said to Obie, ‘I want you to look out behind us, and I’ll look in front of us. We don’t want some goddamn Nip coming out of a hole in the ground and shooting us in the back. We’ll take pictures as we move.’ We didn’t have any trouble. We walked right up to Motoyama No. 1, probably twenty minutes after we landed. I found a fifty-caliber gun mount circled by fifty-gallon drums loaded with sand. The mount was sticking up, but the gun wasn’t there. It made a perfect tent pole, and I covered the whole thing with a big tarp I found nearby. That was my command post.

“I was all dug in and Obie was out shooting stills when finally the guys began to infiltrate in. They’d also been told we’d be somewhere near the end of Motoyama No. 1. We had ten guys shooting motion-picture film. The rest were still men except for a camera repair guy.

“The Navy had noticed in looking at all the film from previous actions that everybody’s footage was the same in every battle: Guys running here, guys running there. So we determined to select and assign various topics to various men. I had a tank battalion, a medical battalion, and a signal battalion I would cover. I had one still man and one movie man assigned to them and nothing else. Out of that came several good training films. One film has a very distinctive name, Glamour Gal, which was painted on the barrel of a howitzer. We also had free roamers, guys attached to a unit, a battalion or a regiment, to document whatever was going on. This way we avoided duplication.

“The whole thing was planned out to the extent that three times a day an LCVP came in from the command ship. It had great big letters across both sides: PRESS. Anybody, meaning civilian press or our public affairs writers or combat correspondents, would go down to that boat and turn their stuff in. It would go to the command ship and then be packaged individually and flown to Guam, where the Navy had a big photo lab set up. They processed all the film. There was total censorship all through the Pacific war, and all military and civilian stuff had to be looked at before it was released.

“That’s how Joe Rosenthal’s shot of the second flag raising and his other stuff was sent in. He went back to the ship in the press boat that night. He went back and forth for four days. There wasn’t any sense in him sleeping on the beach at nighttime, so he’d go back, write his captions, turn his stuff in, and it’d be flown to Guam. So he never saw it until he arrived there around D plus eight. Herb Schlosberg, the photo officer for the Fourth, was on that boat with him. Schlosberg had orders to take all the Marine motion-picture film from D plus one to D plus eight to Washington and to Hollywood, where Warner Brothers could edit the film. We figured it would be smart to have the film edited and ready by the time the battle was over. I took the film between D plus eight and eighteen to Washington.

“For the second flag raising, my boss, Colonel George Roll, the division intelligence officer, came to me and said General Rockey wanted a bigger flag up there because nobody could see the first one, it was so small. I said, ‘Where the hell are they gonna get a bigger flag? Nobody’s carrying any holiday or Sunday flags.’ He said there were LSTs on the beach, and maybe they would find one there. The official Marine Corps position is quite simple: Lieutenant Tuttle, who was an aide to the battalion commander, was sent out to get some supplies from some of those ships and to look at the same time for a larger flag. He was lucky because LST 799, I think it is, had one, and the lieutenant JG gave it to him. It was eight feet long, and if he’d tried to fly it on the stern of the LST, it probably would have dragged in the water.”

Hatch, aware that the marines were going to try to raise a second flag, knew he ought to have someone there to film it.

“I didn’t have anybody to send out, but then in walked Bill Genaust and Bob Campbell to turn in film and get new stuff. I had assigned them to the Twenty-eighth Marines.

“I said, ‘You guys have to turn around and go right back. There’s a possibility that a second flag is going to be put up. Just go up there and sit on top of the mountain and shoot whatever you see, and if a flag goes up, shoot that too.’

“They headed back down. It was kind of dangerous, getting from my CP at the foot of Motoyama No. 1 airstrip over to the mountain. It was a good quarter mile, and there was nothing but firefights going on. But they got over there and ran into Rosenthal going up. He and Bob Campbell had worked on the same newspaper in San Francisco, and they were friends. They joked about going up, and Rosenthal apparently said, ‘Oh, you guys are carrying guns. You can protect me.’ But it was pretty secure on the mountain at that point. They get up there, and it was only seconds later that the second flag went up. They were already putting it on a new pole, and Bob Campbell shot the perfect picture of the one flag coming down, the other going up, crossing each other. This disproved a lot of arguments people have brought up that there weren’t two flags.

“For his part on the summit, Joe had built a little rock cairn to stand on, and Genaust was over to the left of him. But Genaust figured that was not a good shot, so he started to move across, and that’s when Joe said, ‘Hurry up, it’s going up.’ Genaust got on Joe’s right, and that’s the way the shot worked out. Campbell didn’t want to stand next to Rosenthal and get the same picture, so he moved over to the side and down at a lower angle, and that’s how he got that beautiful shot of the two flags.

“When Rosenthal’s stuff came through processing at the Cincpac lab in Guam, somebody, and I don’t know who—nobody’s been able to put a finger on it—whether it was the lab man or the Associated Press photo editor on the island, but somebody made a decision. I always say in a talk, ‘There’s another man involved in the Rosenthal picture.’ He is the person who changed that picture from a horizontal to a vertical, and that made the photo. Because if you look at the horizontal, it shows the top of the mountain, it shows the debris around the place, it shows part of the beach over here, you can even see very faint lines of ships out to sea. It’s got too much crap in it. I’ve said often that if that picture as taken were sent out and printed that way, I don’t know if very many people would have done anything with it. But in turning it into a vertical, he did something that artists, true artists, really like: It’s got a triangle in it; it’s got action in a still photo. You get the feeling of the movement up there, and it tells the story without the caption.

“Of course the picture was a sensation. It was put out the Sunday after Rosenthal took it, and it was on the front page of damn near every major newspaper across the country. Then word got out that it was phony, that it had been staged.

“What happened was Lou Lowery, who shot the first flag raising, got together with a Time-Life correspondent, Bob Sherrod, on the island after we’d heard about this wonderful picture via radio. We hadn’t seen it. This was part of that thing we’d determined at Pearl beforehand: We’d get lots of info back on what the press was saying. Everybody was extolling the wonderful picture. Now Lowery had been up there and was part of that little attack that went on up there and jumped off the side of the mountain and busted both his cameras. He couldn’t understand why this guy who had gone up and just shot a replacement flag was getting all this credit. No combat, no nothing, you know?

“He was pissed off enough that he sat down with Sherrod and he told him the story. He said, ‘There’s something phony about this. It’s just not right.’ Plus a lot of professional photographers thought it was a staged picture from the start.

“What Bob Sherrod told me later was that when he sent it in, he put a note on the piece he had written as a result of talking with Lou. He said, ‘Don’t run this until you check with AP.’ Now that’s good reporting. And they didn’t publish it per se. But there’s always a glitch somewheres. Time-Life in New York at Thirty Rock [Rockefeller Center in midtown Manhattan] was as big as the Pentagon. It was on a great number of floors, and there was also a radio station in there that received copies of all the correspondences going through Time-Life from around the world. So Sherrod’s story comes through all the various stations, goes through this radio desk, and there’s no hold on it; the hold had dropped off somewhere along the line. So they ran with it, U.S. wide, a phony story, phony flag. And then, when Joe hit Guam, he was met by a press conference of his pals saying, ‘What a wonderful picture.’ Well, he hadn’t seen it yet. Someone in the course of asking questions said, ‘Did you pose any pictures?’ He said, ‘Oh, yes, sure.’ Well, he didn’t pose the flag raising, but he did get one of everybody standing around the flagpole. We called that the banzai (or gung ho) shot. It was taken all over the goddamn Pacific. That’s how the misunderstanding arose.

“And that’s what I was up against. The reason I went to Washington was I was taking the film in, from D plus eight to D eighteen, following Herb Schlosberg. I was met at National Airport on March 17 by a lieutenant colonel who was deputy director of public affairs for the Marine Corps. I knew him. His name was Ed Hagenah. I said, ‘Jesus, this is really nice, for a colonel to come over in a car to pick up a warrant officer. I’m really proud.’ He laughed and said, ‘No, I’ve got to take you into headquarters.’ I said, ‘I can’t go like this.’ I hadn’t shaved for a day and a half, I was partly in uniform, still had combat gear on. I had been five days getting from Iwo to Washington.

“He said, ‘Get in the car, and I’ll explain.’ I did so and he told me we were going to the commandant’s office. I said, ‘Oh, for chrissake, Ed. Let me go home and shower and shave, put on a uniform. I only live five minutes away.’ He said no, because in the office waiting for us was the bureau chief of Time-Life in Washington, the executive vice-president of the Associated Press, a bunch of horse holders, and the commandant of the Marine Corps, General A. A. Vandegrift. He said they all wanted to know about the two flag raisings. There was contention about the fact that Time-Life had said Rosenthal’s shot was a phony picture. Now AP wants to sue Time-Life, and it wants to sue Sherrod, and I’m supposed to settle the goddamn argument.

“ ‘That’s all I need,’ I said, ‘to be in the middle of two warring major news organizations.’ So I get there, and the commandant looks at me and kind of grins. He said, ‘Gunner [in those days warrant officers wore the bursting bomb on their covers, or hats, and they were called gunners even though they had nothing to do with guns], he said, ‘Gunner, we don’t know the real story about the two flags. You’re the first one to come back here who might be able fill us in on it. Tell us what the story is.’

“I told them the first flag was put up by the patrol that went up there, and it was considered too small. There was a desire to put up a larger flag, but nobody knew where the hell they’d find one, but they finally did find one on the LST. They took it up and put it up. I said that was all there was to it. It was a replacement flag. I said I thought one of the problems was simply that the AP was calling it the flag raising, and it’s not. The flag raising referred to the one that went up at ten-twenty, the first flag. This one, Genaust and Rosenthal’s, was a replacement flag. Lowery shot the first one. In fact, there is nothing reported in the records about that second flag going up. If you didn’t have a picture of it, you wouldn’t know it was there. The battalion log has nothing; the D-2 log, intelligence, has nothing, the D-3 log, operations, has nothing. It was just a replacement flag, a routine action.

“There was a definite second flag raising, I explained, that had been photographed by Joe Rosenthal, and he hadn’t planned it, he hadn’t promoted it, he hadn’t staged it. So that cleared things up. I hadn’t seen Genaust’s film at all. He was killed March 4, and his film was on the West Coast. The crux came when the commandant said to Alan J. Gould, the senior vice-president who pretty much ran AP, ‘This is a wonderful photo, and I think we could use it a lot in the future. Would you give us permission to use it?’

“The guy said something typical, normal and natural for anybody in that business, with a stock photo library, to say. He told the commandant, ‘Well, yes, I’ll give you a couple duplicate negatives, but it will cost you a dollar apiece for every eight-by-ten that you make.’

“Well, there was dead silence in the room. It felt like icicles. You could feel the horse holders sitting around thinking: If it hadn’t been for the Marine Corps, Rosenthal wouldn’t have been up there taking the picture in the first place, and now they want to charge us for it? So the commandant turned to me, and said, ‘Gunner, what do you think about that?’

“And I thought: Well, here goes nothin’. I said, ‘That is a normal position, for them to come back with a normal response to a request for a stock photo, but if we don’t decide to go with that, we have the sixteen-millimeter color film of the flag raising taken by Bill Genaust and,’ I said, ‘you can always find one frame that’s fairly sharp. We can blow that up to eight-by-ten, make color or black-and-white prints of the exact same shot.’

“Now I didn’t know whether Genaust’s film was underexposed, overexposed, or whether there was dirt or scratches in the film or what the hell might have happened. His motor might have been running slow. I could see the wheels turning over in Gould’s eyes as I was saying this. I could see him thinking there was going to be two pictures out there, one a little fuzzy and the other good and sharp, but the public wouldn’t know the difference. He very quickly came back and said to the commandant, ‘Well, as an afterthought, I’ll give you the two dupe negatives and you can use them in perpetuity at no cost.’ That ended the whole conversation.

“The first thing I did when I got home was call Schlosberg. I got him in the cutting room, and I said, ‘Have you seen Bill Genaust’s film yet?’ He said yes. I said, ‘How is it?’ He said, ‘It’s beautiful.’ I said, ‘Thank God,’ because all I could picture was that if by any chance, the decision had gone the way I suggested and the film was bad, I’d have been shipped to Iceland or someplace.

“At first Lou Lowery was embittered that Joe got all the attention, but once he saw the photo, he didn’t have any doubt that it was a good one, so the animosity sort of drained out of him. But he was pretty bitter there on the beach. He came to me and said, ‘God damn it, what the hell is this?’ I said, ‘Lou, don’t get excited until we find out what it is. We haven’t seen it.’ Later on he and I were very friendly. We worked together on several Marine Corps photo contests as judges. He and Rosenthal became good friends. In fact, Rosenthal came all the way east for Lou’s funeral.

“I never got to know Rosenthal real well, but we talked on the phone over the years. It’d be like, have you heard about this? One of the funniest stories we traded was about some Air Force captain or lieutenant who was having trouble with his P-51 fighter. He put down on the Iwo airstrip, and while he was waiting for the mechanics to fix it, he said, ‘Well, as long as I’m here, I might as well go get a good look at the island.’ So, he said, he walked over and climbed Suribachi just in time to help put the flag up.

“Besides Genaust, we lost one other film guy, Fox, on Iwo after I left. I never did a lot of filming there myself although I went out a couple times. I stayed pretty close to the CP, the command post, in case the colonel needed me.

“I had left the island by the time Genaust was killed March 4. A funny thing happened about ten years ago, 1997 or thereabouts, here at my home in Arlington. I heard a knock on the door one Saturday morning, and a tall gentleman introduced himself as former Lieutenant John K. McLean. He lived right up the street. He said he was an interpreter who was on the patrol when Genaust was killed. A report had come back to division intelligence that a Japanese was sitting at a table in a cave with lots of papers, working on something, but nobody could talk to him. It was thought the papers might be valuable; it was thought it might be a trap, so McLean was sent out with a patrol to find out what this guy was doing. Bill tagged along, looking for a story. It was a rainy, misty day. They got there, and here was this guy sitting at a table down inside this cave, which was quite large. The lieutenant tries to talk to him: ‘Why are you there? What are you doing?’ No answer.

“So the patrol leader says, ‘We’ll go down there and find out what’s happening.’ but he didn’t have a flashlight, and nobody else had one, except Bill. He said, ‘Oh, hell, I got the flashlight. I’ll go down there.’ He was that type. I mean, he’d been in combat. He knew his way around. He knew what to do. But why he did this one, I’ll never know.

“To get into the cave, you had to climb over a large berm formed by dirt taken out of there. There was just enough room to squeeze through. Bill went down into the cave while McLean and two or three other members of the patrol squeezed through behind him. But they didn’t descend. Genaust got two-thirds of the way down there, and a Nambu machine gun opened up from a tunnel off to the right, which they could not see from the entrance. It killed him.

“The Japanese guy starts to pick up his papers, and McLean immediately ordered his men to kill him. But the Nambu scared the living shit out of them, and they turned around and had a hell of a time climbing back out through all that volcanic ash, plus it was so narrow. They were scared to death, and they just piled ass out of there. They got out, but nobody fired at them. Genaust was too far down for anybody to reach without getting shot. So they called for a dozer to close up the cave. McLean, who has since died himself, said he went back a couple days later, but he couldn’t find the cave, and I guess it has been lost ever since.

“Just last week [March 2007] I was at a meeting with a group of Japanese who had come from an organization that looks for bodies, and they were going to make their fifty-fourth or fifty-fifth trip to Iwo and wanted to talk to some marines who had been there during the fighting. The question of Genaust came up, and I gave them a copy of McLean’s story. Of course our own guys have looked for Genaust for years. [At the time this book was going to press, there had been no word from the Japanese contingent.]

“Was the Marine Corps thrilled when the Tarawa film won the Academy Award in ’44? I guess they were. I haven’t the slightest idea. I wasn’t there. General Julian C. Smith, who was the division commander on Tarawa as a major general, was a lieutenant general by then and director of the Department of the Pacific, in San Francisco. He and his wife were invited down to the awards to sit at the table of Twentieth Century Fox, even though they didn’t have anything to do with the film, which was produced by Warner Brothers.

“He accepted the award. I don’t know if you know it or not, but this was not the award. It was a little wooden plaque. Because of the metal shortage, they weren’t making any Oscars during the whole war period. After the war they went back and made Oscars for those who didn’t get any. The Marine Corps Museum’s got it in Quantico. I often used to ask Happy Smith, the general’s wife, whose real name was Harriet, ‘Would you let me take that so I can keep it on my mantel? Whenever the general passes on, I’ll turn it in, to the Marine Corps historical people.’ But she never would agree to that. It was kind of a joke between us. Still, I thought it would be kind of nice to have that plaque sitting there on my mantelpiece.”

After a hitch in Japan during the occupation, Norman Hatch wound up back in Washington as an operations officer for photographic services for the Marine Corps, first as a military man, then in 1946 as a civilian. He and his wife, Lois, had a son, Skip, and later a daughter, Colby. Following that, he worked in procurement, then joined Bell & Howell in Chicago for a stretch, did some freelancing back east, and finally, in July 1956, became the chief of the Defense Department’s newsreel setup, where he spent the next twenty-three years. As newsreels phased out, he created a radio-TV-newsfilm branch and then became operations officer for the audiovisual division. There he came to work with folks like John Wayne, who wanted Marine Corps authenticity in his film The Green Berets.

“John Wayne was fine to work with. He was emotionally involved with his project, and he thought it was wonderful and great, and it was pretty good in the sense that it didn’t hurt the service any, but there were little things that aggravated us, relationships he portrayed that were farfetched. But then he built a whole Vietnamese village at Fort Benning and gave it to the Army to train guys.

“I retired as a major in January 1979, after forty-one years’ service. There were several retirements in there: the Marine Corps, the Defense Department. It’s like I’ve been on the crest of a wave ever since I got out of the Marine Corps. I went from one good job to another. Now I am doing something like this interview for this book, I just did a similar thing for somebody writing an article, and they’re asking me now to write for the Second Marine Division newsletter. Everybody’s asking me to write a book, a fellow in New Zealand is writing a book, and I got to dictate something for him, so I’m busier now than I was before.”