Chuck Lindberg in his Richfield, Minnesota, home on May 8, 2007, when he granted an interview to the author, who took this photograph. Lindberg’s Silver Star and his Purple Heart rest beside him on the arm of his easy chair.

CORPORAL CHARLES “CHUCK” LINDBERG

Last of the Flag Raisers; Silver Star, Purple Heart

Twenty-eighth Marines, Fifth Marine Division

It still bugs me that we never got recognition for being the first to raise the flag on Iwo Jima.

Chuck Lindberg in his Richfield, Minnesota, home on May 8, 2007, when he granted an interview to the author, who took this photograph. Lindberg’s Silver Star and his Purple Heart rest beside him on the arm of his easy chair.

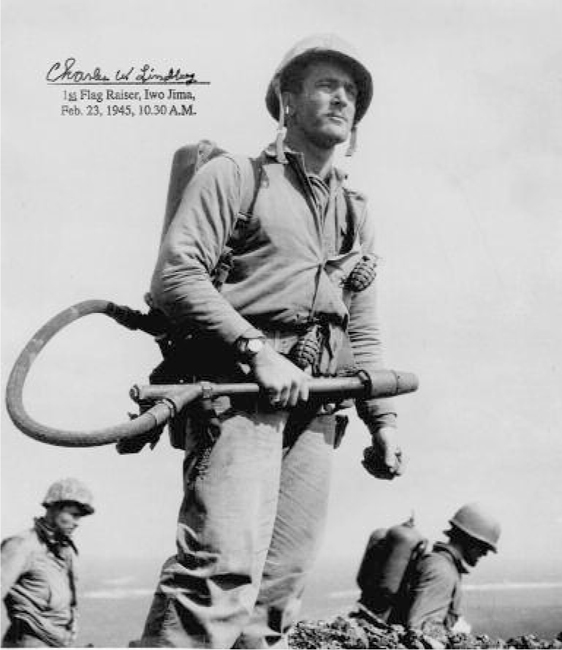

Corporal Charles W. Lindberg, grenades hanging off his jacket, flamethrower in hand, looks for cave entrances along the summit of Mount Suribachi shortly after the first flag was raised on the morning of February 23, 1945.

I was sitting talking with Chuck Lindberg and his wife, Vi (for Violette), in the living room of the modest Minneapolis home they had shared for more than fifty years when I noticed after some time that half the forefinger on his left hand was missing. Thinking it got shot off in the war, I asked about it. But no, he had lost it as a twelve-year-old reaching into some rocks at a dam, trying to catch a bullhead, when the rocks loosened, came down, and crushed the front part of the finger. “Them days,” Chuck said, “they didn’t have what they have today or they could have saved it. But when I got to the Marine Corps recruiter in Seattle in 1942, he took a look at it and said, ‘Is that your trigger finger?’ I said, ‘Nope.’ And he said, ‘You’re accepted.’ I couldn’t get in now, if I wanted to, with a finger like that.”

“I’m from Grand Forks, North Dakota. I was born June 26, 1920. I quit high school in tenth grade, in 1937, and joined the Civilian Conservation Corps, the CCCs, planting trees, down around Fargo, mostly, for about six months or a year. When that ended, I went to work on a farm outside Grand Forks, getting a whole ten dollars a month in the winter and twenty-five dollars in the summer. One winter day this big Lincoln Zephyr pulled up in the yard. As soon as the driver got, out I recognized him as Archie Simonson, a man I used to take care of horses for back in my school days. He owned three or four gas stations in Fargo, Grand Forks, and St. Cloud. He kept some big workhorses up there and sent them down to the woods for the winter. I took care of them for him. He remembered me and where I was. He said he was starting a gas station in Fargo and he’d give me ninety dollars a month and a room. Oh, boy! I jumped this high.

“I worked for him about a year and then got acquainted with the road boss of some truckers hauling cars. I asked him one day, ‘Hey, I’d like to get another job and get out of here.’ He says, ‘I’ll give you a job. You can make yourself two hundred forty bucks a month.’ Pretty soon I was driving a big truck hauling cars from Detroit to Spokane.

“That was my big move. I drove truck till war was declared, and then, when I found out two months later there was no more cars to be delivered, I went up to the Marine Corps. It was January of ’42, and I was stranded in Spokane. I always had great respect for the Marine Corps, from books, posters, and movies. I joined in January 8,1942. I knew the draft would get me eventually anyway. I was single; I was twenty-one. I had six brothers and three sisters. My folks didn’t know I was in the Marines until I wrote home. By the time they got it I was on my way overseas.

“I had to go to Seattle to get sworn in. They sent me to boot camp in San Diego. When you’re driving trucks all the time, you get weak, and boot camp was tough even though it only lasted five weeks. Them marines don’t monkey around. The day we finished boot camp they marched us down to the parade grounds, and here was a big platform and Carlson (Lieutenant Colonel E. F. Carlson) and Jimmy Roosevelt was there. But Carlson was talking, recruiting men for his raider outfit. He says, ‘I want men who ain’t afraid to die, I want men who ain’t afraid to kill. I want men who’ll walk fifty miles in a day.’ I raised my hand. I put my like in him right away. I liked his way of talking. They sent us up to Jacques Farm for training; they put us in pup tents on the crick. There was a house sitting there, and I thought, first thing, I thought there’s where the officers are going to sleep. But about ten o’clock that night here come the officers, all of ’em, and they get in the pup tents. That’s the way he run it. He’d eat, sleep, and go with the men all the time. The officers didn’t get fed any better. We liked that.

“I stayed with them until they were disbanded, after Guadalcanal and Bougainville. We come into Guadalcanal November 2 at Aola Bay and went on what they called the Long Patrol, thirty-two days behind enemy lines, from November 4 to December 4, 1942. It was said to be the longest patrol of World War Two. I was a rifleman. [Lieutenant Colonel Carlson led the guerrilla raid, for which he received a Navy Cross. His men were credited with killing 488 Japanese while 16 raiders were killed and 18 wounded.]

“After that we went to Hebrides, and then they called us back north again. I was a private first class. Later we made the invasion of Bougainville in 1943. We were there three months, and then they brought us back to the States, disbanded the raiders, like they did the paratroopers, and put us all in the Fifth Marine Division. After I returned from leave to Camp Pendleton, I saw the flamethrower unit and volunteered for it. Everybody said I was nuts, but I made corporal, and they gave me an assault squad. I was five feet ten and weighed a hundred seventy pounds. The flamethrower weighed seventy-two pounds. It carried five gallons of jellied gasoline, and you could empty it in six seconds.

“After several months at Pendleton, we went to the Big Island at Hawaii and trained more there, at Camp Tarawa. From there it was on to Iwo. We didn’t have too good info on that island. From Hawaii we stopped at Guam and switched from big ships to LSTs. Was it bumpy? Oh, Jesus, you can say that again. It went plop plop plop through the sea.

“I was in the Third Platoon of E Company, Second Battalion, Twenty-eighth Marines, under John Keith Wells until he got injured. Then Lieutenant Harold Schrier took over. We came in next to Suribachi in the eighth or ninth wave. Kuribayashi opened up when we come ashore. It was really bloody, with guys lying all over the place. They mortared us up and down the beach. They had it all bracketed. I found out later their plan was to let us get on the beach and annihilate us. But we got off the beach and up behind the sand ridges. There were tunnels and mines and booby traps all around Suribachi. I was used to combat, so that never worried me too much. We got to the base of the mountain February 21. We got across the island and cut Suribachi off that first day. We thought we were really doing something.

“We spent the next few days attacking the mountain, taking out caves, pillboxes. I never seen so many caves and bunkers. Ever bunker was attached to another one, and they’d go by one connector on down fifteen feet, and then someone would come up behind and shoot you in the back. Our casualties was high on that Third Platoon.

“With the flamethrower you had to sneak up on them, and once you got within thirty or forty feet you could use it. It would reach sixty feet under good conditions. Once you sent that load of gas in there, you didn’t have to worry too much, as long as they didn’t have another way out. I can’t say how many I hit, maybe ten or fifteen. The biggest one I got was on top of the mountain when we went up at eight a.m. on February 23, forty of us. I was on that first combat patrol with Schrier. They came the night before and said we were going to start climbing in the morning. We had a kind of jittery night. The next morning we reported to Colonel Chandler Johnson, who handed Schrier a flag and said, ‘If you get to the top, raise it.’ We thought it was going to be a slaughterhouse, but it turned out we went up that mountain with no resistance.

“I was back a bit. The scouts and riflemen go first. We didn’t hit the cave right away. The first thing they told us was to get the flag up. When we got there, I took the flamethrower off and laid it beside me. We found a water pipe to tie the flag to laying on the ground. It was about four inches thick and twenty feet long. It was heavy. I helped tie the flag on with Thomas and Schrier and Hansen. Then we went to the highest spot we could find and stood it up. It hit my helmet going up and knocked it off. There were horns honking, guys cheering; it was just wild. All the ships out there tooting their horns. We felt very good about it.

In his excellent account of all aspects of both flag raisings, Uncommon Valor, Common Virtue: Iwo Jima and the Photograph that Captured America, Hal Buell quotes Chuck Lindberg from an oral history collection, Never in Doubt: “It was a great patriotic feeling, this chill that runs through you. . . . My proudest moment of my time in the Marines was raising the American flag on Iwo Jima. My feeling of being a Marine is I served with the finest, and I feel proud every day that I can tell somebody that.”

“Once we put up the flag, the Japs started coming out of the caves. I know the first one we got wasn’t more than one hundred or two hundred feet from where we put up the flag. And we were right near the edge where you go over to go down where that cave went in. I went around the back of it and found another entrance. Somebody had dropped something big and knocked a hole in the cave. I sent a good blast in there. The other guys were standing on top, trying to get something to shoot at, but nobody came out. We thought that was kind of funny, so we blew both ends of that cave shut. Then two days later we dug it open, went in there, and found seventy-two dead Japs. My theory has always been that before we started up that mountain, they ordered barrages and Colonel Johnson just pulverized it, with planes, battlewagons, the whole thing. I think they were afraid to come out. Then, after we got up there, they started shooting at us from this one cave, and that’s the one we went after first. It sat right on the rim of the volcano, a big rocky opening.

“You know about Donald Ruhl, who got the Medal of Honor? Before we went up the mountain, he and Hansen were down on edge of a big hole, looking for targets for me, and all of a sudden a grenade came over, right between them. I was right directly back. Ruhl he just gave Hansen a shove, and he fell on it. He was a good man; there was no doubt. The trouble is, you know, then Hansen was killed March 1, the same day I was shot. [In addition to falling on the grenade on February 21, Ruhl was cited for his bravery over the previous three days in attacking the enemy and rescuing under heavy fire a wounded fellow marine.]

“Sergeant Lou Lowery, the Leatherneck magazine photographer who took the pictures of our flag raising, was trying to get away from a grenade when he fell down the side of the mountain and busted his camera. I knew him very well. Lowery was with us off and on. He was unhappy, he told me after, when Rosenthal’s photo got all the attention. He was unhappy over that. I was very good friends with him after the war too. I even went to his funeral at Quantico, after he died in 1973. The thing that got me was here come Joe Rosenthal too. He took the second flag raising picture. ‘Oh,’ he says, ‘you were on the real one, wasn’t ya?’ He wasn’t told to do that, in my opinion. He wanted a picture, and he was going to get a picture. Oh, you bet. It’s a good picture. I even told Rosenthal it was a good picture. But me and him got into a few arguments.

“How did I feel about it? It still bugs me that we never got recognition for being the first to raise the flag on Iwo Jima. Why, here you were doing the dirty work, and they get the credit for it. They were called heroes. The mountain was secured. All they did was come up, put the flag up, and go back down again. And when I got home and started talking about this, I was called a liar and everything else. It was terrible.

“We spent from the twenty-third to the twenty-eighth on the summit. I reloaded and went back up several times because there were a lot of places we wanted to burn up there. You didn’t know if they were in there or not and you couldn’t blast them out, so you used the flamethrower. I and Robert Goode were flamethrowers for the company. I had a whole squad, and where we were needed, we went.

“We moved on the twenty-eighth, went up to Hill 362 Able. We stayed there the first night, and then the next night Hansen was shot. We were all settin’, kind of got to talking, when all of a sudden a sniper nailed him right there, at noon. And that’s where I was shot, March 1, that same afternoon. I was trying to get to a mortar position, kind of running across the side of a ridge there, and all of sudden—boom!—a bullet went right straight through my right forearm and on through my jacket. I was bent over like this, and if I’d been standing straight, another inch or two, it would have got me. But because I was bent over, it missed my stomach. It shattered my forearm bone. You bet I went down. I hollered, ‘Corpsman,’ and here come John Bradley, from the second flag raising. I knew him very good. He was our platoon corpsman, a wonderful corpsman, I’ll tell you that. He was from Wisconsin [Bradley’s son James, with Ron Powers, wrote Flags of Our Fathers, the best-selling story of those who raised the second flag and the basis for the Clint Eastwood film]. We saw each other after the war, and I saw them in Chicago when they were on that bond drive. I was back in Great Lakes Hospital by then.

“Anyways, I’m on the ground lying there, not feeling too bad. He got some splints on it and gave me a shot of some kind. He was going to take me back, but I said, ‘No, I’ll go by myself,’ which I did. I left the flamethrower behind. I walked from Hill 362 to the beach; I didn’t know if I could make it or not. It was a long way too. When I got to the Higgins boat, they stripped me of all my equipment, my rifle, pistol, the works, and away I go. They set my arm on the hospital ship, but I got the best deal when I got back to Pearl Harbor. They really worked on it.

“I went from the hospital ship at Iwo to Saipan. After about a week a guy says to me, ‘You want to see a picture of the flag raising?’ I said sure. He hands me a picture, I look at it, and that’s not the one we put up. I didn’t know a thing about it. Nobody said anything about it. I was astounded. After they sent me on to Pearl Harbor, Yank magazine came out with pictures of the first flag and the second flag, and then I saw what happened.

“But we hadn’t known the flag was being replaced. Nobody said anything about it. We were busy hitting caves when the second patrol came up with big flag. We had the mountain secure by one o’clock, and I went down to the bottom because my tanks were empty. I was being assisted by Robert Goode. We left the mountain at one-thirty, went straight down, and Rosenthal came up over to the other side. I didn’t see him go up. I don’t think anybody knew the flag was being replaced. Nobody cheered. Everybody knew the flag was up. They weren’t paying attention to that anymore. If it were not for the photo, nobody would have noticed. The mountain was secure when he came up there. He didn’t go under fire. We didn’t even go up under fire. Nobody fired at us.

“Rosenthal pulled a rotten trick there, I thought. He was behind that second flag; he was going to get a picture. They weren’t going to use ours. Give us our share of credit for what we did. People today don’t know the difference. They called him a hero, called the six men who raised the second flag heroes when they sat at the bottom while we went up. To their credit, they didn’t consider themselves heroes.

“I talked to them guys on the bond drive when I was at the Great Lakes Naval Hospital in Chicago, where I spent several months after being treated in Guam, Hawaii, and Camp Pendleton; that’s where they cured me. We found out they were going to be at Wrigley Field, so I and another guy went down there. Huge crowd. They were really eating that up. That Gagnon, he got me. He introduced me around as a guy that killed a lot of men. I didn’t like him as well. He wanted to be in the movies. Bradley introduced me to other people too. We didn’t talk too long. My arm was still in a cast. I never talked to Gagnon.

“I kind of felt sorry for Ira Hayes, the Indian. He did it wrong [lost control of his life], but he was a good marine. He was a paratrooper. I talked to him quite a bit. We came back on the same ship together, seventeen days from Guadalcanal to San Diego. He’d drink, but it wasn’t that way [not to excess]. I imagine everybody had some. I took a drink myself.

“After that they sent me down to Charleston, South Carolina, and made me a guard in the naval brig for two or three months. That was an easy racket. I was discharged down there January 16, 1946. When they pay you, they pay you from where you enlisted at. I had enlisted in Seattle and was discharged in Charleston, so that was a nice check, including travel pay for all that distance.

“I met my wife, Vi, in November of 1946 at the Legion Hall in East Grand Forks, Minnesota. I belonged to it. I was a past commander of the post. I was the bouncer, and I let them in free, four good-looking girls. She’s from Minnesota. We got married in October 1947. We had two sons and two daughters.

“I was an electrician by then, wiring farms up there. I had run into an old friend in Grand Forks that I used to work for long ago, and he says, ‘Can you wire a house?’ I said, ‘I don’t know.’ I tried it, and I guess I got it wired all right, with a few mistakes. That was my start in the electrical trade, and I did that for thirty-nine years, IBEW Local 292 Minneapolis. I retired in 1985. Two years ago they put up a new building in St. Michael’s for training apprentices, and they told me they were going to name it after me, the Charles Chuck Lindberg Training Center.

“We had some attention for raising the flag but just not what you’d think, not like those other guys got. I was invited to Washington quite a few times. I was there for the dedication of the flag raising monument in 1964. Harold Schrier was there, and Lou Lowery. Nobody recognized us at all. Eisenhower was there. Nixon was vice president. I shook hands with him. He was shaking hands with me and looking over at somebody else. I met President Clinton and went to the dedication of the new Marine Corps Museum in Quantico November of 2006. I got sent a lot of stuff, and you ought to see the statue they got of me in Bemidji. It’s beautiful, six feet tall, over in the center of the state. Vi and I went to Washington on a private plane, just the two of us for the Veterans Day dedication of the new museum last November. Seven of us were there from the Third Platoon. That’s all that were left.

“It’s taken half a century, but I think I’ve finally helped set the record straight.”

On February 24, 2001, then eighty-year-old Charles Lindberg was presented with a letter from the commandant of the Marine Corps honoring him for his role in the raising of the U.S. flag at Iwo Jima. Lindberg also holds a Purple Heart, of course, and the Silver Star, awarded for his performance at Suribachi and on Hill 362. Part of the citation reads:

Repeatedly exposing himself to hostile grenades and machine-gun fire in order that he might reach and neutralize enemy pillboxes at the base of Mount Suribachi, Corporal Lindberg courageously approached within ten or fifteen yards of the emplacements before discharging his weapon, thereby assuring the annihilation of the enemy and the successful completion of his platoon’s mission. While engaged in an attack on hostile cave positions on March 1, he fearlessly exposed himself to accurate enemy fire and was subsequently wounded and evacuated.

Chuck Lindberg died on Sunday, June 26, only weeks after I visited with him and his wife at their Richfield, Minnesota, home on May 8. He and Vi had been married fifty-nine years.