15

MACHINIST’S MATE THIRD CLASS PERLE “DUSTY” WARD

133rd Seabee Battalion

Because I was born and raised on a farm and could run a tractor and drive horses, different things like that, they thought that I ought to be able to run a bulldozer.

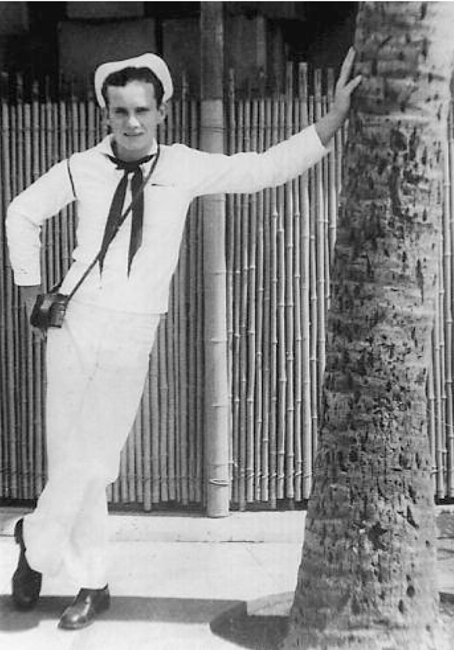

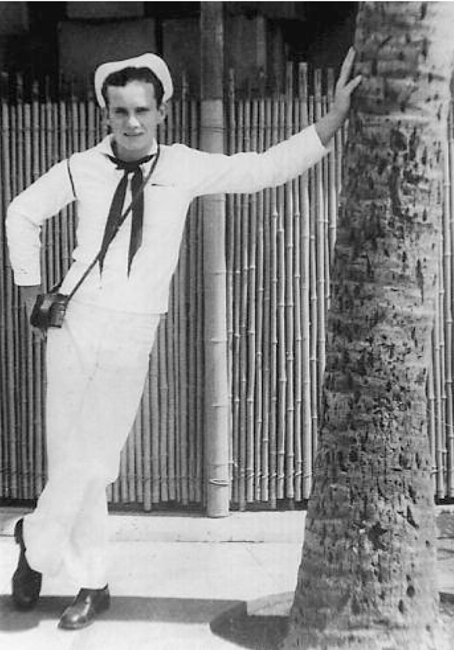

The young Seabee Seaman First Class Dusty Ward leans against a palm tree in Honolulu in 1944. He received an official commendation for helping evacuate casualties on D-day on Iwo Jima, working all night as a stretcher bearer to bring in wounded marines. “His activities contributed materially to the saving of many lives,” the citation says.

I did not know, when I reached Dusty Ward by phone at his home near San Diego, that Mabel, his wife of fifty-four years, had died only days before, on April 7, 2007. “We just finished her memorial last Saturday at the Elks Lodge here in El Cajon,” he said. “It turned out to be a beautiful one. I’m just sitting here looking at a bunch of flowers, and I started out this morning to write thank-you cards to all the people that sent flowers. I made up my mind I was going to get to it this morning and not stop till I’m done. She wasn’t that old. She was only seventy-two. The poor gal had a lot of things went wrong with her.”

“I came into Iwo Jima February 19, 1945, on an LST. Going into shore, I remember an LST coming in next to me, and as soon as they dropped the damn ramp, a mortar shell hit right on the ramp as guys were coming off. I don’t know how many were killed, but it was right alongside me. So talk about being lucky, I feel that way. And that was the first day. No heavy machinery came in. They probably started moving it late in the second day. Our job was to help get other equipment inland.

“I got involved in a deal late in the afternoon of the first day where some officer from the Fourth Marine Division came and asked for volunteers to carry some wounded back. I was one of the four that volunteered. We carried them on litters, maybe as many as thirty guys, one after the other, after they had been treated by the corpsmen. Of course there were shells they were bombarding us with, but none came too close. The Japanese could shoot artillery or come out of their caves and rapidly fire off a couple mortars and duck back inside. They felt pretty safe. They had the range to hit any place on the island. Everything was bracketed.

“Well, this went on longer than we anticipated, way into the wee hours of the next morning, till two-thirty or three o’clock. We had left our outfit on the beach because we hadn’t been landed too long, and when we came back, our outfit had moved. So there we were four of us, alone in enemy territory, and it was dark. We felt the enemy had a big advantage over us, knowing the terrain and one thing and another, so we were smart enough to dig a foxhole for the night. And that’s where we stayed until the next morning.

“When daylight came, we went looking for our outfit, and after asking different people, we finally found them a few hundred yards up the beach, going away from Suribachi. When we got there, my CO [commanding officer] said one of us had to report. They designated me, and then he pointed up a hill and said, ‘See those two officers standing up there? Report to them, and tell them briefly what happened last night and why you weren’t with your outfit.’

“So I walked those fifty yards up the hill and talked to a Marine lieutenant colonel and a Marine major, probably from the Fourth Division. I briefly told them what had happened, how we came ashore and they asked for volunteers to carry wounded marines from inland to the beach to be sent out to the hospital ship. Turned out to be a longer job than we anticipated and we had to dig a foxhole and stay the night. When morning came, we started looking, and here we are, I said. One of them thanked me.

“This whole thing took probably a minute and a half. So I turned around and walked down the hill toward where my guys had already dug a foxhole for me near the beach. I got forty or fifty foot from them when a mortar landed just where the three of us had been standing. Of course it killed the major and the lieutenant colonel of Marines, and it blew me from that forty or fifty foot away clear on down, head first, into my foxhole. When I come up, I had a little blood on my left hand. Guys were kidding me about going down to the beach to the hospital tent and get it fixed. Anyway, I still can see a couple scars, so I don’t know whether a piece of shrapnel hit me from that far away or whether the sand cut it when the concussion blew me into the foxhole. Turned out to be minor. But anyway, that was our first day and the first morning of our second day on Iwo. Why were they killed and me spared? The good Lord was looking out for me. It was also a good thing I didn’t take too long to make my report.

“Seabees was kind of a moniker. It came from the NCB, which stood for Naval Construction Battalion. Our job was to unload ships and build or repair roads and airstrips. We were part of the Navy, but on Iwo Jima we were attached to the Fourth Marine Division. We wore Marine uniforms and were subject to Marine regulations.

“We also had the carryall, as we called it. Road graders they call them nowadays. I was born in 1926. I’m one of these dummies. I had some illnesses when I was young, and I quit school in eighth grade, when I was sixteen, and never got back to it. My dad had a sixty-acre farm, cows, horses, pigs, chickens, and a John Deere. Because I was born and raised on a farm and could run a tractor and drive horses, different things like that, they thought that I ought be able to run a bulldozer.

“I grew up near Armada in the Thumb district of Michigan. My given name was Perle, but somewhere along the line they took to calling me Dusty, because I used to get pretty dirty when I was a kid. I’m sure glad they didn’t call me Dirty. But I lived with Dusty, and that’s what most people know me as ever since.”

Wouldn’t Perle just confuse people anyway?

“Yeah. I was always mad at my grandmother on my father’s side. That was her responsibility for giving me that name. I give my four kids all simple names like Pam, Deb, Bob, and Mike.

“Anyway, my older brother was in, and I knew it was just a matter of time before they’d draft me. It looked like the war was going to last for a while, so I just went down to the recruiting office in Detroit one day. I was going to join the Navy, but they talked about the Seabees and convinced me that was the way to go. I enlisted August 14 of 1943. I didn’t know any better. I’d do it all over again, but I don’t know if I’d have that much luck.

“We had basic training at Camp Perry in Virginia, and they give us the same training as they give the Marines. You had these drill instructors putting you through the ropes. Mainly it was just indoctrination, getting used to what the service was going be like, fundamentals. We didn’t get into guns until we got to Camp Endicott at Providence, Rhode Island. We were there until the first part of 1944, and then we went to Biloxi, Mississippi, for more training, as I recall.

“We were trained with guns just like the Marines because we might get in a situation where we needed to defend ourselves, and then we were learning heavy equipment for road building and basic construction. The equipment was not armored. We crawled under live fire, through barricades, and learned how to knock down wire barriers. It was pretty advanced training as we moved along.

“We went from Biloxi to a camp in California between Oxnard and Ventura. We had bulldozers; we called them Cats for Caterpillar and road graders and road wheelers that tamped dirt on the airstrips. From there we went to Hickam Field in Hawaii. We were organized in platoons and companies. I was in the One Hundred Thirty-third Seabees, which turned out to have the most casualties, as I understand it, of any Seabee unit in history [reports vary, from 245 to 370, with at least 3 officers and 39 enlisted men killed].

“We had several more weeks’ training at Hickam and then got on ships, headed out, and rendezvoused with the Fourth Marine Division, going to Iwo Jima. It was my first combat. I was just a wet-nosed kid, eighteen years old, a machinist’s mate third class. The job was to defend yourself and build roads and airstrips. The equipment bogged down real fast in that coral ash when they tried to get it off the LSTs. We had these landing mats you put together to cross a bad area. They were folded and fit together by hooks. They were wide enough to drive over with jeeps or heavy equipment. We did the same thing on the airstrip, Motoyama No. 1, later on as temporary measure. We had the dozers or Cats; road graders and road tampers—heavy rollers—come in the belly of the LSTs later on.

“Before we could get our nose into things, you had to move the enemy out of there. We tried to stay alive and help organize things on the beach as we moved inland. Our job was to set up whatever they wanted, to assist the Fourth Marine Division, whatever their commanders wanted us to do, relayed to us through our officers.”

According to a Seabee staff correspondent, Robert V. Evans, there were two battalions from the 41st Seabee Regiment at Iwo Jima, the 133rd, Dusty Ward’s, attached to the Fourth Division, and the 31st Naval Construction Battalion, which was attached to the Fifth Marine Division. He reported that, following Seabee repairs, the southern airfield, Motoyama No. 1, was in use by February 26, a week after the invasion.

“We were there from February until the end of November. We stayed there long after the battle was over, built the airfields back up for B-29s to land, all that sort of stuff. We got shot at while driving the equipment, but that was about it. Those bulldozers were heavily made, so generally bullets would just glance off the blades and the metal parts. You were totally exposed, no armor other than the blade. Some guys got shot. Like I say, I was one of the lucky ones. We worked on Motoyama No.1 and No. 2, either rebuilding or refurbishing when there were bomb and shell craters, and then we maintained them as long as we were on the island. I saw Dinah Might land March 4, when it took out the telephone pole with one wing. I also saw B-29s come later with three motors gone, and I saw one hit the end of the runway where it dropped off onto a pretty steep bluff. It went right into the end of that thing and blew itself up.

“As far as what was on the island was concerned, there was no material value. Nobody would want that piece of land. But from the standpoint of strategic maneuvering, it was a good decision on America’s part to take that island. They saved a lot of planes and a lot of lives coming back from bombing runs to Japan. They feel it saved something like twenty to twenty-five thousand lives, plus all those planes.

“When we left that November, we stopped by Guam on our way back to the States. We were originally supposed to go to San Francisco, but for some reason, after we passed Hawaii, they decided to go to Seattle. We got there 19 December 1945. They gave us the choice to stay there and get discharged, which would delay our getting home for Christmas, or we could leave immediately, maybe make it home by Christmas, and get discharged later on. I chose to leave immediately. We took a train, and I’ll always remember, after coming from the sunny South Pacific all that time, riding through these big snowbanks in Montana and places like that.

“Anyway, I walked into my family farmhouse at seven o’clock Christmas Eve 1945. My mom said I made quite a Christmas present. She was there and my father and younger brother would have been there. My older brother was Air Force, stationed in the Pacific. My discharge was delayed till the fourteenth of March 1946.

“I left Michigan before the winter of 1947 rolled around. I was spoiled by the Pacific, and I couldn’t stand that cold weather anymore. My brother’s got the farm, and he’s got that same John Deere my dad owned. I ran it for a while after I got out of the service. It’s still going strong. But then I went to California, and I’ve been here ever since.”

Dusty fetched up in the San Fernando Valley and owned a gas station for a while, then went into real estate. He sold vacuum cleaners door-to-door, connected with Sears in the late forties and spent thirty-five years with the company, most of it in management, working all over California and Arizona. His last assignment took him to San Diego, and that was how he ended up in El Cajon, where he lives to this day.

He met Mabel in Riverside, California, during his first department manager job. He was told he was being promoted to a position in San Jose. Shortly after, he and Mabel were at dinner with one of her girlfriends one night.

“They knew I was going to San Jose, and I said something like, ‘How are we going to work this?’ And the girlfriend said, ‘Well, why don’t you guys up and go to Vegas and get married, and then you can go to San Jose together?’

“So that’s what we did. It happened to be a Saturday night, and it happened to be my birthday, March 19, 1954. We went to Las Vegas and got married at the old Hitching Post, and that was it. We didn’t think about it at the time, but had it worked out differently I wouldn’t have wanted it on my birthday.

“I think the Seabees were a good outfit. Back on Iwo, we didn’t have time to socialize much with other units. We stuck to our own area. It was pretty fast-paced, and they kept you pretty busy. I liked the bulldozer. All those years the Seabees never got credit for what they did. We should have received a Presidential Unit Citation, though. But I enjoyed my part in them. I’m glad it’s behind me now; I feel lucky to be alive.

“My most vivid memory of Iwo was probably those six or seven seconds when I walked away from the major and the lieutenant colonel on the beach and how lucky I was. If I had been a long-winded guy and stood there another six seconds, I wouldn’t be here today. I have probably lived that moment a thousand times since then and realize that no matter how good or bad in life you might be, luck has to play a very important part. The full realization of what happened to me that day has made me a better person, and I thank the good Lord for guiding me and putting me down the hill away from that artillery explosion. Of course the good part would be that I would have never known about it, because that Marine lieutenant colonel and major never knew what hit ’em. Their lives went out. There was no suffering there. There wouldn’t have been with me either. I got to have a life instead.”