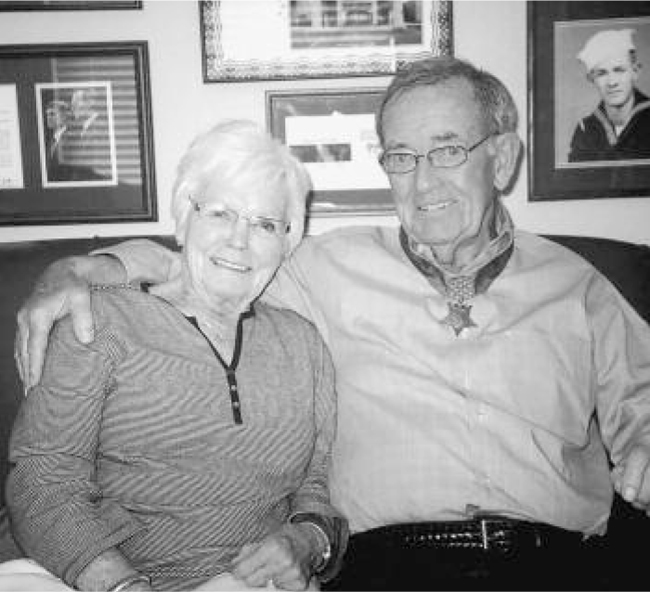

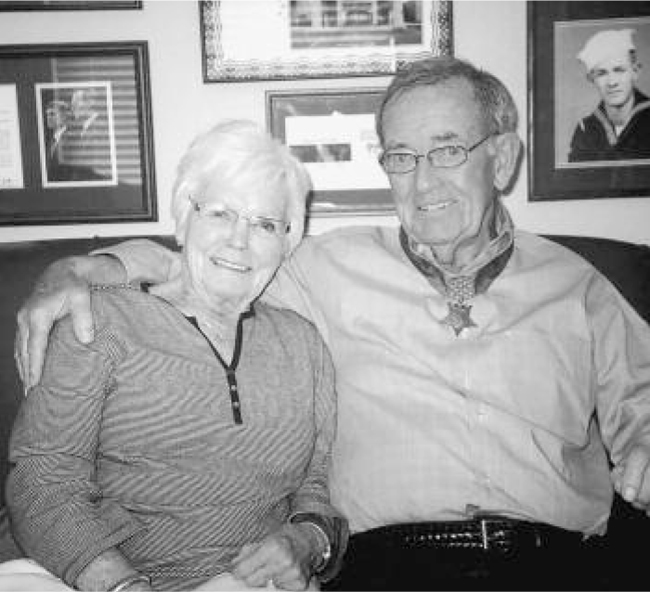

George Wahlen and Melba, his gracious and charming wife, in their Roy, Utah, home in May 2007. By the following August they had been married sixtyone years. A photo of George as a young corpsman hangs on the wall to his left.

PHARMACIST’S MATE THIRD CLASS GEORGE WAHLEN

Navy Corpsman; Medal of Honor

Twenty-sixth Marines, Fifth Marine Division

[T]he last week aboard ship I think is the first time I ever prayed in my life. And in my prayer I always asked the Lord, I said, “If there’s anything at all you can do, don’t let me let one of my buddies down.”

George Wahlen and Melba, his gracious and charming wife, in their Roy, Utah, home in May 2007. By the following August they had been married sixtyone years. A photo of George as a young corpsman hangs on the wall to his left.

Knees shaking, the last of fourteen men honored that afternoon, a petrified young pharmacist’s mate, the first living corpsman to receive the Medal of Honor in World War II, is greeted by President Truman, who snatches his hand and says, “It’s mighty good to see a pill pusher here in the middle of all these marines.” Then he put the medal around George Wahlen’s neck.

Two days before I was scheduled to fly to Roy, Utah, to visit George Wahlen in May 2007, he called to say he had just been hospitalized and maybe we should reschedule. When he found out my plane tickets were fixed, however, he offered to let me conduct the interview in his hospital room. Happily, he had been released by the time I got there, and I had a most enjoyable visit with him and his wife, Melba. Though George was not initially religious, he eventually joined the Church of Jesus Christ of the Latter-day Saints, and he and Melba went on to have five children, twenty-six grandchildren, and thirty-seven great grandchildren. I asked Melba how she handled all those birthdays. “It’s simple,” she said. “I just send each one a card and a two-dollar bill.”

“I was born August 8, 1924. I was one of three boys. My father farmed, and later we moved into Ogden, Utah. My father had never been in the military, and he was kind of scared of what would happen to me if I went in, but he did let me quit school my senior year to take an aircraft engine mechanic’s course at a college in Logan. Pearl Harbor was attacked the day after I enrolled. It was a six-month course, but I went for three and then had an opportunity to go to Hill Air Force Base near Ogden. I worked there several months. My dad still wouldn’t let me join the service, but I went down and volunteered in June of 1943. I tried to join the Army Air Corps, but they said they were all filled up, so then I tried the Navy because I was told they had planes.

“I went by train to the Naval Training Center in San Diego for basic training June 18. I had a hard time learning to march. When I finished, they sent me to hospital corps school instead of aircraft mechanic’s school. I tried to talk them out of it, but no one would listen. They told me if I did well, they might reconsider after I graduated, but that was baloney.

“I learned basic first aid; then they put me in a medical ward at the Naval Hospital in Balboa Park, San Diego, changing bedpans, cleaning floors, and being ordered around by female nurses. I was promoted to pharmacist’s mate third class. I remember some nurse I didn’t like got mad at me for not emptying some bedpans, and she said, ‘If you don’t shape up, I’m going to send you to the Marine Corps!’

“I thought about that and said to myself, ‘I’m not going to be sent; I’ll go volunteer.’ I went and done it that day, and next morning I had my seabag all packed and went to the Marine Corps for seven weeks of further training. They sent me to Camp Elliott, gave me a Marine Corps uniform, and we had seven weeks of training, learning how to dress shrapnel wounds, splint bones, and treat an open belly wound. Instead of taking care of people in a ward and following a doctor or nurse’s instruction, you had to learn how to treat wounds on the battlefield. Lots of times you get involved with sick ones too.

“I was in the Navy, but I was attached to the Marines and wore a Marine uniform. The Marine Corps medics were all Navy corpsmen. We had three months of training, including weapons. I trained with a carbine, the Browning automatic rifle, machine guns, hand grenades, forty-fives, everything. We got the same training as an infantryman. You were expected to know how to act in combat because you were in combat, same as the Marines. You were being shot at and exposed just the same as they was. You had no insignia showing you as a medic at all. You didn’t want to; they claimed that was more dangerous. My pharmacist’s rating translated me to a three-stripe sergeant. I was assigned to the Fifth Marine Division, which was activated January 1944. I was in Fox Company, Second Battalion, Twenty-sixth Marine Regiment.

“We sailed to Hawaii in late July 1944 and spent six months there at Camp Tarawa on the Big Island. We reached Saipan February 11, 1945, and left for Iwo on February 16.

“By now we knew where we were going. I remember the last week aboard ship I think is the first time I ever prayed in my life. And in my prayer I always asked the Lord, I said, ‘If there’s anything at all you can do, don’t let me let one of my buddies down.’ For a nonreligious person, the comradeship you had with those marines was something that doesn’t often happen in your lifetime. The thought of letting one of them down just really bothered me, and I think that’s the feeling inside that I had. I would probably rather have been dead than let one of those guys down and know that I did. I worried about it before we went into combat.

“We went ashore late afternoon at Red Beach Two. There were bodies everywhere. We were in reserve, but we were also supposed to be protecting the left flank of the Twenty-seventh Marines. Three days went by without me having to treat a bad wound in my unit. The first one I treated, Lieutenant James Cassidy, died of a bullet wound near the heart.

“Then on D plus three, February 22, a shell blew the right leg off my platoon sergeant, Joe Malone. It also took the fingers of his right hand and the right side of his face. There was sand and thread from his dungarees in the stump of his leg, and I got a tourniquet on it and a battle dressing, wrapped his hand, and gave him a shot of morphine. Then I wrapped his face. The skin was peeled away, and his teeth, gums, and cheekbone were exposed. But he survived. A litter crew came and took him out of there.

“I was trying to catch up with my platoon after that, but then I heard another wounded marine moaning, and I crawled over to him. A machine gun had cut across his stomach, exposing his intestines. The important thing with this kind of wound is to keep it moist, so I soaked a battle dressing from my medical bag with canteen water and put that on and then gave him a shot. I went on from there and treated a man from my platoon. It went like that.” [There were 120 killed from George’s battalion that day alone.]

“I quit carrying my carbine, gave it away to a BAR man, because it just got in the way. About ten a.m. on the seventh day Fox Company was sent forward to relieve Easy Company. It started to rain. We’d move forward, but then the Japanese would follow in tunnels underneath and come out and attack us from the rear in areas we thought were secure.

“The Second Platoon was crossing a flat, open area about an acre in size when the Japanese waited for the right minute, then hit us with mortar and machine guns. I was trying to stay with my unit, but then I turned and saw about fifteen marines down, still under attack from mortars and artillery fire. My friend Eddie Monjaras was their corpsman, and I didn’t see him out there.

“I crawled out and dragged a marine with a leg wound into a shell hole, wrapped him, then went out and crawled from man to man. I found Eddie, finally. He was hit in the chest and stomach. I treated him, but he died later. They tried to have two corpsmen assigned to a platoon, but they was lucky to have one, I think. Mortar kept falling, but I kept going until I got to them all, through about twenty minutes of it.

“I assessed the injuries, usually by the state of their clothes and by how much they were bleeding. As I remember, we did have scissors, but I don’t remember using them. Under combat you’d do whatever you could to take care of the problem. Getting shot at and everything, you just didn’t want to do any more than you had to to get the job done. Those I treated were all laying out there pretty much not moving, all exposed. I just crawled to each one of them, I think there were fourteen, and done that, took care of them. I remember I finally got back to my own team. I remember laying there thinking about what had happened. I was still there. I was amazed I survived. Not even scratched. How do you explain it? I’ve often wondered.

“I have no idea how or why I survived, without even a scratch. I crawled into a shell hole and got the shakes as I thought about it. I was worn out. But the platoon was moving again, so I followed. We were right near Hill 362A. Later that day a grenade went off as I was crawling, and several pieces of shrapnel cut my face. I couldn’t see out of my right eye and I was bleeding, and I got a dressing out and wrapped the side of my face.

“I heard a call for a corpsman and I started crawling toward a wounded marine, but grenades kept landing near him. I finally saw a Japanese soldier come out of a cave on the hill and throw a fourth grenade. All I had was my forty-five, so I yelled down to some guys to throw me some grenades. They did so. Then I took some shrapnel in the rear and legs from another grenade as I crawled up toward the cave. I wanted to throw mine when he was coming out, but I couldn’t pull the pin. The marine had bent it over, for safety. I straightened it with my Ka-Bar. I crawled up close enough, and after he threw out the next one, as I remember, I pulled it out and waited for a couple seconds before I threw it in, so it would go off right away. I knew those things could come back at you, and I didn’t want to give him time to grab it and throw it.

“He jumped out, and my grenade got him. Then I went to treat the wounded marine, and I dragged him down the hill. His leg was torn up, the calf all exposed. Somebody came with a litter after a while, and we got him down and out. After that George Long, another corpsman, and I took care of several casualties. Then I went back for supplies because Long refused my order to go.

“My captain, Frank Caldwell, was at the command post, and he saw me all bloody with a bandage over my face and told me to go down to the aid station. But instead I just grabbed a bunch of bandages and battle dressings and things and headed back to my unit. He saw me two or three days later. I was still with my platoon, and he said, ‘I thought I told you to go back.’ I said, ‘Sir, I was still needed.’

“I’ll always remember one particular time when we had this marine brought back to me screaming and out of it. I was in a shell hole, and we held him down, and I gave him a shot of morphine. He got pretty quiet after laying there awhile; then I got involved taking care of more casualties up ahead. I finally come back to see if they got him evacuated, which I’d hoped to do. But he wasn’t there, and I never seen him again until the reunions years later back here in the States. Our company commander asked everybody to speak a little bit, and so I did. A guy come up from the back of the group and started to cry. He said, ‘Doc, you saved my life.’ I didn’t know who it was because he had a beard. I talked to him afterwards, and it turned out he was the guy who had cracked up. He says, ‘If you hadn’t of left me there, I would never have made it.’ But he was one of the five out of two hundred fifty in my company that survived the whole thing.”

By that night Wahlen had treated more than twenty of the forty-nine casualties suffered by Fox Company, according to his story, told in the book The Quiet Hero, by Gary Toyn. Eighteen were killed in action. The company was relieved the next day.

“We stayed in reserve until February 28, D plus nine, then it was back to 362A. We wound up alone on the front after the 327 pulled back, and Fox came under attack that night. Hill 362A was declared secure March 1. Fox Company had almost one hundred casualties with twenty-seven killed.”

On D plus eleven Wahlen’s company was in support of the 128 when several marines were shot and the corpsmen were busy. Near Hill 326B on Nishi Ridge, Wahlen crawled out to treat a marine whose legs were badly injured by a mortar shell. He was dragging the man to a safer spot when a shell went off behind and knocked George flying. When he came to, he could barely move, but he finally managed to crawl down the hill and into a shell hole, where he asked another marine to look at his back, which was badly gouged. He had the marine clean the wound and sprinkle sulfa powder on it, then wrap it with a battle dressing.

He continued to treat injured marines the next day as Fox Company was assigned to circle around Hill 362B as part of the assault. By noon it had gained three hundred yards, and by midafternoon it was moving up the hill. Then, around 4:00 p.m., Wahlen was rocked by a large artillery shell that landed on a number of marines in a shell hole.

“My strongest memory of Iwo was what turned out to be my last day in combat. As we were going up north, a group got hit with heavy fire, and as I was crawling up there, I got hit in the leg. There was casualties right in front of me, so I started to get up, but I couldn’t. I looked down at my foot, and part of my boot had been torn away, and my right leg was all bloody and broken just above the ankle. I pulled my boot off and put a battle dressing on it and give myself a shot of morphine. Then I crawled up to where the marines were. As I remember, there were about five of them, and they were all pretty well shot up. I think one guy lost a leg, and others were all beat up. I worked with them and bandaged them and give them morphine as long as I could. Finally they were evacuated. Then somebody out to our left flank got hit and started hollering for a corpsman, so I crawled out on hands and knees and took care of him too. He could have been forty or fifty yards out there, so I crawled out and bandaged him up, and we crawled to a shell hole. Finally we was both evacuated.

“The stretcher bearers came for us but then dropped me when rifle fire came. I got out my forty-five and started crawling toward the enemy. It was the morphine. They finally came and got me and took me to the aid station. Four of us went from there on a truck to the field hospital. My war was over. I think it was March 3. I was scared myself plenty of times. I always remember that feeling of being scared, but the thought of letting somebody down scared me even more.” [Only 82 remained of the 250 in Fox Company that landed on D-day.]

“They finally got me on a ship next morning and took me to Guam. After several days there they flew me to Pearl Harbor. The leg was not healing well, and they sent me from there to a naval hospital in Oakland and then down to the U.S. Naval Hospital at Camp Pendleton. I had several surgeries because they couldn’t get the blood to flow downward, and I was afraid I was going to lose my lower leg. It was months before I could walk on it.

“When I got home, I met my wife, and she was Mormon, so later on I joined the church. I had to give up smoking first, and that was a problem. I learned to smoke when I was with the Marines. I think when I got started, I was in the hospital there at Camp Pendleton. I remember spending all that time with those marines out on the porch, and they’re all smoking. Every time you got up in the morning there’d be a pack of cigarettes on your bunk. I smoked whatever they gave me; I wasn’t particular.

“I got the Navy Cross with a gold star [signifying two] when I was at Pendleton, and then in September they told me about the Medal of Honor. I flew to Washington, D.C., alone, and met my mother and father there and two aunts and uncles. There was fourteen Medals of Honor awarded that day, October 5, 1945, including Woody Williams [Chapter 5] and Franklin Sigler, who was in my company. Neither of us knew the other would be there. Here were all these generals and admirals and brass, and I was nervous. I believe I was the first living Navy corpsman in World War Two to get the Medal of Honor. I couldn’t imagine something like that happening to me.

“As I remember, I was the last of the fourteen to receive my medal, and all that time here were all these high-ranking people sitting out there watching us. For a Navy corpsman to receive the Medal of Honor is almost unbelievable, so I was pretty nervous. Here’s me, a lowly corpsman, shaking hands with the president. It was almost unimaginable. So when President Truman finally got to me, I started shaking. He saw it and grabbed my hand and said, ‘It’s mighty good to see a pill pusher here in the middle of all these marines.’ Then he put the medal around my neck. I was not tall, five feet eight, and I weighed probably one hundred twenty.”

Wahlen had violent nightmares for months after he came home. He went to junior college. Then an Army recruiter came after him, and once he was assured he could stay around as a recruiter himself, Wahlen went into the Army as a master sergeant.

“I kinda hesitated, thinking about going back to school. Then he promised me a tour on the recruiting side, and I wanted to get married, so I decided to go in. The medal was the reason they wanted me. Public speaking was a little tough on me, and I didn’t like publicity, but I had to get over that.”

He and Melba Holley married in August 1946, before he went back into the service. They had met on a blind date. Her father was opposed to the relationship at first because she was only seventeen, and George was a sailor, he took a drink now and then, and he smoked.

“I got sent to Japan from 1952 to ’54, went to Korea in 1963, and I was in Vietnam during the Tet offensive in 1968. Somewhere along the line I ended up getting commissioned as a lieutenant. I retired in 1969, worked for the state, then spent ten years with the Veterans Administration in Salt Lake City.”

Years went by before Melba even knew about George’s Medal of Honor.

“She found out about it when we got our first invitation to go to a medal ceremony in the Rose Garden with President Kennedy. I didn’t pass the word around.”

Nobody ever asked him to return the Navy Cross and Gold Star, which were superseded by the Medal of Honor. And of course he holds two Purple Hearts.

George finally managed to quit smoking and became a full-fledged Mormon.

WAHLEN, GEORGE EDWARD

Rank and organization: Pharmacist’s Mate Second [sic] Class, U.S. Navy, serving with 2d Battalion, 26th Marines, 5th Marine Division. Place and date: Iwo Jima, Volcano Islands group, 3 March 1945. Entered service at: Utah. Born: 8 August 1924, Ogden, Utah.

Medal of Honor Citation:

For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty while serving with the 2d Battalion, 26th Marines, 5th Marine Division, during action against enemy Japanese forces on Iwo Jima in the Volcano group on 3 March 1945. Painfully wounded in the bitter action on 26 February, Wahlen remained on the battlefield, advancing well forward of the frontlines to aid a wounded marine and carrying him back to safety despite a terrific concentration of fire. Tireless in his ministrations, he consistently disregarded all danger to attend his fighting comrades as they fell under the devastating rain of shrapnel and bullets, and rendered prompt assistance to various elements of his combat group as required. When an adjacent platoon suffered heavy casualties, he defied the continuous pounding of heavy mortars and deadly fire of enemy rifles to care for the wounded, working rapidly in an area swept by constant fire and treating 14 casualties before returning to his own platoon. Wounded again on 2 March, he gallantly refused evacuation, moving out with his company the following day in a furious assault across 600 yards of open terrain and repeatedly rendering medical aid while exposed to the blasting fury of powerful Japanese guns. Stout-hearted and indomitable, he persevered in his determined efforts as his unit waged fierce battle and, unable to walk after sustaining a third agonizing wound, resolutely crawled 50 yards to administer first aid to still another fallen fighter. By his dauntless fortitude and valor, Wahlen served as a constant inspiration and contributed vitally to the high morale of his company during critical phases of this strategically important engagement. His heroic spirit of self-sacrifice in the face of overwhelming enemy fire upheld the highest traditions of the U.S. Naval Service.