Phil True at eighty-one near his home in Fairfax, Virginia, in the fall of 2006

B-29 Navigator

Ninety-ninth Squadron, Ninth Bomb Group

I gave a talk about the significance of Iwo for those of us in the Twentieth Air Force and the many lives saved, including mine, because of the Marines’ heroism in taking that ugly piece of rock and sand. Yes, I did land there three times, and I am eternally grateful for the island and the Marines.

Phil True at eighty-one near his home in Fairfax, Virginia, in the fall of 2006

Second Lieutenant Phil True, nineteen, in a photo he says was probably taken at home in Jackson, Michigan, when he was given two weeks’ leave after receiving his navigator wings, with a globe in the center, on December 15, 1944. On his lapel is the Army Air Forces insignia, a wing with a propeller through it.

I spoke with Phil True at length over the phone, and his feeling for the Marines was evident. In 1997, when he was talked into being chairman of a reunion for his Ninth Bomb Group, he chose to honor the Marines for capturing Iwo Jima. “I organized a tribute featuring the Marine Drum and Bugle Corps,” he told me, “and located members of the Third, Fourth, and Fifth Marine Divisions, who had invaded Iwo. They spoke, as did our commanding officer during the war and the colonel in charge of the Marine Barracks. We held it at the Marine Corps Memorial on August 28. We had close to three hundred people. Afterward I was asked to be an honorary Marine with Chapter Twenty-five of the Fourth Marine Division.” He has continued his association with the Corps.

“I live in Fairfax, Virginia, now, but I grew up in southern Michigan, near Jackson. I was born April 14, 1925. I was the first person in my immediate family to graduate from high school. My father and mother, like most farmers, quit school in ninth or tenth grade. There was a junior college in town, and when I got out of high school, I decided to go there. When Pearl Harbor came, the draft age was twenty, and I really didn’t think about going into the service. But then it was lowered in the fall of 1942, while I was in junior college, and I realized I’d be facing the draft the following spring, after I turned eighteen.

“Very few people went to college in those days, and the Navy and the Army assumed anybody in college was ‘smart’ and therefore officer training material. They had these specialized training programs, and I think in February of ’43 the Army Air Forces, as it was called then, set up their aviation cadet program. Although almost every kid my age was interested in flying, for me it wasn’t that I just had to fly. It wasn’t that kind of thing. They had a little bonus. They said if you signed up, you could be called up sometime after you were eighteen and there would be a five-month college program.

“I took the physical and a written test, and I was sworn into the Army Air Forces three days before I turned eighteen. In fact, I was the first seventeen-year-old to do that in Jackson. I was called up August of 1943 and went through the entire training program. The aviation program was roughly a year. You had to go through basic, and then it depended on how you were classified: If you were going to be a pilot, you went to primary training, then advanced training. You’d be commissioned. Then, if you were going to be a bomber pilot, you’d go through multiengine school.

“Of course taking it didn’t mean you were in it. The washout rates were maybe fifty percent. A lot of people didn’t have the ability to do this.

“We did our basic training, from early September through early November, in Miami Beach. The reason was that when the war started, they simply did not have enough Army barracks built throughout the country to house everybody. So they used the War Powers Act to requisition hotels after the tourist season was over. I think in April of 1942 about ninety percent of the hotels in Miami Beach were being used. They had close to a hundred thousand people undergoing basic training in South Florida.

“While I was down there, they decided to give us classification tests, two days of written tests and what they called psychomotor tests, devised to try to determine if you were best suited to be a pilot, navigator, or a bombardier. Some people didn’t qualify for any, so they were sent to radio school or gunnery school.

“Anyhow, I qualified for all three, but my highest score was for navigation. We had ten hours of dual flight instruction in little two-seater Piper Cubs before we got sent up to Allegheny College in Pennsylvania in mid-November of ’43. I learned after the war the college training program, the Army Air Forces cadet program, was set up because the small liberal arts colleges had been drained of students except for women. They sort of struck a deal that they would put these training detachments in from the Air Forces, and provide them with money. There were about four hundred of us and about a thousand coeds, so you could see the ratio was actually pretty good.

“As for the flying, I sort of enjoyed it, I guess, but I was rational enough to realize I wasn’t a natural. I could put the plane in a stall and recover, but getting it to spin was not my forte. When I got down to preflight school in San Antonio in March of ’44 I already knew my scores because when you were a student at Allegheny, you had to pull junior officer of the day, and so late at night, when no officers were around, you looked up your file. I discovered what my scores were and decided I would be a navigator.

“I went through preflight school, which ended in June of ’44. Normally most people went on to gunnery school, but about four hundred of us in our class stayed on and went to the San Antonio Aviation Cadet Center, which is now Lackland Air Force Base. We waited around for shipping orders, and it got to be mid-August, and there was hardly anybody left when they received a direct call for people up at San Marcos near Austin. I was in this remaining group, so I went directly to navigation school instead of gunnery school. We were still not commissioned. We were essentially privates in the Army. There were fifty in my class, and I think thirty-one of us graduated. The attrition rate was high.

“We had actually four basic ways to navigate. One was through dead reckoning; that was simply through your instruments, using the compass and airspeed. You had to compute your drift, of course. You had to use maps, to figure out your declination in terms of your compass heading. We had a log, we called it a navigator’s log. I had eight or ten columns of data that had to be entered in for any particular time to get your true airspeed. Then you got your ground position from that. Then you had radio, depending on where you were. Then you had celestial navigation, based on figuring your position from the stars. And finally you had what you called pilotage, which was just looking out the window. ‘What do you see out there?’ There were sectional air maps that provided good detail for what you were seeing on the ground.

“We actually had twenty practice missions. Each mission had three student navigators, and we’d have a three-legged triangular mission. One student would be lead navigator on each leg while the other two would follow what he was doing. The next student would plot the next leg and so on.

“We flew in a twin-engine Beechcraft, and it wasn’t until the final mission or two that we were allowed to use all four navigational tools. If you had a zero zero mission, that meant you were perfect in figuring your ETA, your estimated time of arrival, and reaching your destination. You might be two minutes and five miles off, but that was considered reasonably good. It was a sixteen-week course. I graduated in December of 1944 and became a second lieutenant.

“We got some home leave, and I went back to San Marcos about New Year’s. Somebody got sick, and an opening came up so I went to Lincoln, Nebraska, which was a classification center. They were making up crews to send to various bases for training. I didn’t have any gunnery training, so they put me in a B-29 program because the navigator in a B-29 did not handle a gun. Our crew assembled about the first of February in Tucson, Arizona, and trained there until about the first of May.

“From there we went up to Wichita, Kansas, to pick up a B-29 to fly overseas. It took a couple of weeks to get it ready. We had to do a series of things, make sure the instruments were calibrated and so on. The citizens of Manhattan, Kansas, had had a bond drive to pay for a new B-29. It took about six hundred thousand bucks, if you can imagine that. They wanted to name the plane, and they had a contest and came up with Nip Finale, and that was painted on its nose. It’s not politically correct now, of course, but that was our plane, and we enjoyed it.

“In late May we flew to California and took off from a field near Sacramento, then to Oahu, on to Johnson Island, and eventually we reached Kwajalein, which the Marines had taken I guess, in late 1944. It was just a flat atoll. The control tower there wasn’t much. The airstrip was probably eight thousand feet long. I remember they had a sign up there in the operations office. It said: KWAJALEIN ATOLL, ELEVATION EIGHT FEET, NO WHISKEY ATALL, NO WOMEN ATALL, NO NOTHING ATALL.

“Next day we flew out to Tinian, where the Three Hundred Thirteenth Wing was located. We landed, and the pilot went to report, and one of the ground crew came up, dressed only in a pair of shorts, and he says, ‘Where’s the whiskey?’ One of the guys, I guess the engineer, said, ‘We didn’t bring any whiskey.’ What? No, we didn’t bring anything. I heard the guy say, ‘Didn’t bring anything?’ Whiskey was a great barter item. Actually one of our gunners had wanted to, but our pilot—he was a major—was very strict on rules and regulations.

“Anyway, we did not keep the plane. You make the mistake of thinking just because you fly a plane, it’s yours. That plane was taken to one of the groups that needed it more than the Ninth Bomb Group, where we were assigned. A number of years later, when I got reunited with my crew, I did some checking and discovered that Nip Finale had been taken over by the Five Hundred Fourth Bomb Group, which was one of four in the Three Hundred Thirteenth Wing. There was the Ninth, the Five Hundred Fourth, the Five Hundred Fifth, and the Sixth Bomb Group. Each group had about forty planes and crews. I learned the Nip Finale got in twenty missions. It was the third plane for that ground crew. Their previous two had been shot down.”

Phil True was in the 99th Squadron of the Ninth Bomb Group in the 313th Wing. Each bomb group consisted of three squadrons, each with fifteen planes. There were five bomb groups in the Pacific at the end of the war: the 73rd, in Saipan; the 313th, on Tinian; the 58th, on Tinian; the 314th Wing, on Guam; and the 315th, on Guam. Each wing had four bomb groups, for a total of twenty.

“We flew whatever plane was available. Crews didn’t necessarily fly the same plane every time. Engines needed replacing frequently, and when your ship was in for repair, you flew whatever was available. Some crews flew as many as thirty-five missions, but they would fly maybe twenty-five or so on ‘their’ plane. So you never knew what plane you were going to fly. There would be an announcement that such and such crews would be briefing at eleven o’clock that night, twenty-three hundred, whatever; it was going to be a daylight mission. Then you would have a little breakfast, get in the truck, and go down the line. Then you’d find out which plane you were going to fly.

“We’d get down there, and one of the problems for the navigator was you had to take the astro compass and make sure everything was aligned correctly. You used the North Star normally to do that. On some planes the compass reading was maybe a couple of degrees off from what you were actually doing. You always had to make little corrections. Occasionally planes got caught in smoke thermals, and some of them got twisted two or three degrees, so you and the compass in the plane didn’t quite agree.

“We flew some practice missions, bombing the airfield of an island called Pagan, in the Northern Marianas, about halfway between Iwo and Saipan and Tinian. I think there were a few Japanese left but no defenses. The B-29 could carry eight tons of bombs, but most missions you carried seven, depending on whether you had incendiaries. There were five hundred, thousand, and two thousand pounders.

“Our first mission over Japan was June 4 to 5. We took off on the fourth and bombed Kobe. We didn’t fly in formation to Japan. That would have taken too much gasoline. We flew up separately, then used some sort of reference point; often it was just a compass point in the ocean. It was a very, very tricky job to get so many planes in formation once you got there. Each group had a slightly different certain altitude and a slightly different location. Then, at a certain time, they all had to fly to the IP, the initial point, from where you went on your bomb run. It was an intricate job.

“About four hundred fifty planes went over the target, in formation. There was a high overcast, so we flew a daylight mission at fourteen or fifteen thousand feet, which was very low. This put you in easy range of all the antiaircraft they had. The city was well defended, and the Japanese put up a couple of hundred fighter planes. About a dozen B-29s were shot down, and seventy-five were damaged.

“I went along as observer on that particular raid. I sat in a nose hatch right behind the pilot, copilot, and bombardier. Apparently what happened was the fighters came in after we dropped the bombs.

“They didn’t attack during the bombing run, when they could get in the flak themselves. Normally the fighters would attack before you got in, or just after. Fighters came at us, usually in pairs. Mainly they’d fly head-on through the formations. The Japanese had three or four aces on B-29s. Some had shot down as many as fifteen planes.

“When the main force of Japanese fighters were coming from, say, twelve o’clock, straight overhead, there would be two or three of these aces, or better pilots, who would fly a couple thousand feet below a formation. They’d pick out a plane, and because the gunners were all looking ahead and because there was a slight dead spot on the B-29 right directly below, they would come right up under it to within a couple hundred feet and then fire their twenty-millimeter cannon shells into the wing tanks.

“That happened to our plane, although we didn’t realize it at first. Then one of the gunners called in and said gasoline was coming out behind number three. Gasoline was from a wing tank, of course, and number three was the inboard engine on the right-hand side of plane. The pilot immediately shut down the engine and then feathered the propellers. Feathering meant you altered the pitch of the blades so they offered less air resistance. We feathered that engine, and then, ten or fifteen minutes later, the supply of gasoline to number four, which was the outboard engine on the right-hand side of the plane, ran out because the fuel tank had been hit. There was no way to transfer any additional fuel out there on this particular model B-29.

“So we feathered number four, and tried to restart number three, but I think the starter motor had burnt out. It may have been hit. Anyway, number three and number four engines were not working. By that time we were just leaving Japan, and a buddy ship flew with us for three or four hours. The pilot put the plane on what you’d call a climb setting, put the nose like he was going to climb, but because he didn’t have enough power we just kind of mushed our way.

“We lost altitude till we got down around four or five thousand feet. Here the air was heavy enough so we could level off. But we still did not have much gasoline, and the pilot thought about having us bail out when we got to a picket ship, a Navy destroyer escort. But then he decided the water was too cold for him to jump. So he said we’d try to make Iwo.

“It was a stormy day. We got to Iwo, and the pilot was being very careful. He was too high, so the tower told him to do a go around, which was a little tricky. In fact, it was not recommended at all on a B-29. We had to go around the island with two dead engines. With that right-side wing down, it was very hard to control the plane.

“After the first go-round, we came in with flaps down, wheels down, and then, just a couple hundred feet above the runway, another B-29 cut right in front of us. In fact, I read a report many years later that said the air control was not good that day; pilots were not obeying the tower. Apparently this guy had wounded on board.

So we had to pull up. Any kind of little flicker on the remaining two engines would have been the end of us. The pilot said, ‘If we can’t get in this time, I’m going to dump you out over the ocean. I’ll try to climb to fifteen hundred feet and let you out.’ So we came around a third time, and this time, as we came in to land, visibility was essentially zero. But the tower had elementary radar, and they picked us up and guided us in. We screeched to a halt at the end of the fighter strip. We had maybe ten minutes of gas left. That was my first, and almost my last, mission. That’s my story of getting saved on Iwo Jima.

“We landed twice again in June while on two other missions, but it was primarily because we were on the margins with our gas supply. If you were based on Tinian and you were returning with less than two thousand gallons, you were supposed to land on Iwo to take on more.

“Something wrong with the engines was discovered when we landed, and they said we had to hitchhike aboard another 29 that was going back to Tinian. And just as we took off, boom, one of its engines conked out. The pilot said, ‘Hell, we can get back on three.’ But then, an hour later, ping! another engine went out on the other side, and he said, ‘Well, we gotta go back to Iwo now.’ A friend of mine in college after the war had been in B-24s in Italy, and he was talking about planes. I said, ‘Well you know, a B-29 can fly with two engines out on the same side,’ and he said, ‘You’re nuts, you can’t do that.’ But I know, because we did.

“We flew twelve missions before our crew was selected in late July to come back and be trained as a lead crew to lead a group or squadron in bombing. There was so much bad weather over Japan you had to rely on radar bombing. About a dozen crews were being sent back each month. Then in August the war ended.

“Of course the first B-29 to land on Iwo was Dinah Might, on D plus thirteen, March 4. Lieutenant Raymond Malo, the pilot, was from my Ninth Bomb Group, Ninety-ninth Squadron. They had flown a mission over Tokyo, and their bomb bay doors had frozen open, and they had a fuel transfer problem. The Seabees said, ‘You give us a couple hours, and we’ll have another thousand feet of runway.’ Malo said, ‘No, thanks, I’m going to take off. I want to get out of here.’ He didn’t stay long.

“His plane was later shot down, on April 14, over Kawasaki. Malo and the entire crew were killed. Our group lost four planes that night. Another navigator took the cot of Malo’s navigator in the Quonset hut where we were going to be living. Three or four days before we arrived in Nip Finale, the second navigator’s plane was taking off on a night mining mission, and something happened on the runway: The plane skidded off, and the mines exploded. The tailgunner survived, but everybody else was killed. So when I got to this Quonset hut, I took this empty cot. After a few days the guy next to me told me the story. He said, ‘You know, Malo’s navigator had this cot, and then Caldwell’s navigator had this cot, so welcome to the cot.’

“Do I think the seizure of Iwo Jima was worth the cost? Yes, I do, because around twenty-two hundred B-29s landed there after it was taken, although it’s difficult to say how many crewmen would have been lost otherwise. Some planes were low on gas but would have got back anyway. And if you had to bail out, you had maybe a forty percent chance of survival. And the P-51 wing was located there as well.

“While we were sitting there at that reunion at the Marine Corps Memorial in 1997, two buses with Japanese calligraphy on the side came along, and out jumped a bunch of Japanese tourists. We had a dozen marines there, and one rushed over and told them to get back in the bus. I thought it was kind of ironic.

“I got discharged in mid-December 1945. I was only in for not quite two and a half years, but it seemed long enough to me. Besides, I was only eighteen when I started.

“I went back to Jackson, took a semester of junior college, then went to Western Michigan University in Kalamazoo. I graduated from there in 1948, ending up with a major in geography. I went on to the University of Chicago, where I got a master’s in geography and taught for a year before a friend said they were hiring for the CIA, and I said, ‘What’s the CIA. Is that the CIO?’ Anyhow, that’s how I came to Washington.

“I worked forty-seven years in the CIA. I was on the analytic side, which meant I didn’t go into phone booths and leave pencil marks. I worked primarily on China, and then I retired and worked on contract and then worked primarily in training and ran some courses. Most of the people I found at the CIA were very dedicated people. It’s not a perfect organization, it’s obvious. They certainly made a serious mistake in the 2002 October NIE [National Intelligence Estimate]. That’s another story.

“I got married to Fern Brooks September 1949. I told this story at our fiftieth wedding anniversary: I was taking a speech class at the junior college in Jackson. It met early in the morning. It was wintertime; it was February 1946; it was cold. There were not many people in the class.

“I sat in the back row, and there was a young lady named Lenore Larsen. She was blond, pretty good-looking, liked to wear sweaters. She’d come in late most of the time, and she’d sit in the back of the room as well. She’d take off her coat, and then she’d stretch. So this friend, Warren Tisch, and I would kind of eyeball that. And after two or three weeks the professor said, ‘Why don’t we just move people around?’ He said, ‘Mr. True, there’s an empty chair right up here.’ And that’s where my wife-to-be was sitting, though I didn’t know her at that time. So it was proximity and Lenore Larsen that led me to my bride. She came from a farm family too. We had two boys and a girl.

“I was invited along with some other people four years ago when they opened up the Air and Space Museum out at Dulles. The Enola Gay, the B-29 that dropped the atom bomb on Hiroshima, was there. Eight or nine of us from the Ninth Bomb Group were going to get a picture taken next to the Enola Gay, and a Japanese TV crew came up and asked if they could interview me. I simply said, ‘I think it [dropping the bomb] was cruel in many ways, but I think in the long run it saved more lives than were lost.’ Despite the fact that their navy had been largely defeated, the Japanese were not in the mood to surrender.

“I was asked to say a few words at a memorial service on behalf of B-29s at a Fourth Marine Division reunion in Washington, D.C., in 2002. And at an Iwo symposium in 2005 I gave a talk about the significance of Iwo for those of us in the Twentieth Air Force and the many lives saved, including mine, because of the Marines’ heroism in taking that ugly piece of rock and sand. Yes, I did land there three times, and I am eternally grateful for the island and the Marines.”

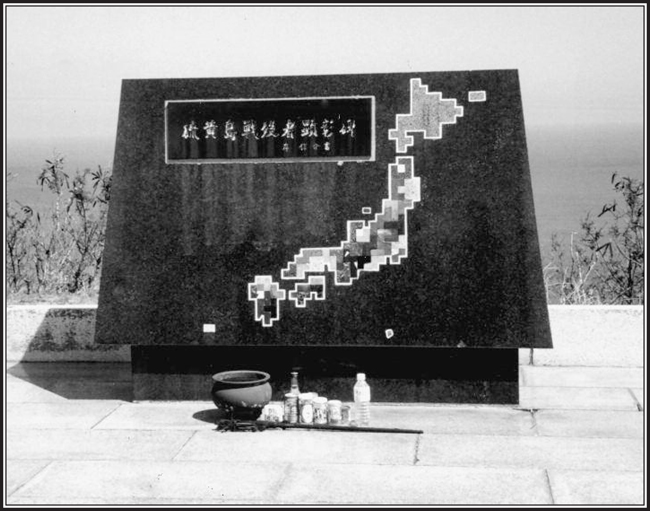

The characters on this monument, erected on the summit of Mount Suribachi after Iwo

Jima and the Ogasawara (Bonin) Islands were returned to Japan on June 26, 1968, say:

“The Monument to Pay Tribute to the Soldiers Who Fought and Died on Iwo Jima.”

The map on the surface of the monument consists of stones from each prefecture

of Japan, and an epitaph on an accompanying memorial reads:

A small force pitted against a mighty army

On a lonely island, where even the deities are in awe.

For thousands of years, love and hate disappear

And the fragrance of sincerity spreads over eternity.

(translated by Masahide Mizoguchi)

The small bottles and objects at the base of the

memorial represent offerings to the dead.