America at the start of the 21st century has often been described as a society dominated by the mass media, and so we are. How often have we heard someone say that if something doesn’t happen in the media it “didn’t happen”? And, of course, how much do we really know about the world beyond our immediate surroundings that doesn’t come to us via the media? But what is it that makes important the images we see on television and on the movie screen, the stories that we read in newspapers, magazines, and books, the songs we listen and dance to? Why do they play such important roles in our lives? How did the media, and television in particular, acquire such power in a society of over 250 million people? Given the many ways in which we receive information about our society and our world—from parents and peers, teachers and preachers—how is it that the mass media have become so uniquely powerful?

The answer lies in the changes in technology and society in the past century. The world has become a single giant organism, whether we like it or not, and its nervous system is telecommunications. Modern industrial society has become ever more integrated and homogeneous—teenagers around the world at this moment are watching American-made music videos on Japanese-made television sets—and very few communities or individuals remain islands isolated from the media mainstream. Our knowledge of the world beyond our immediate surroundings is made up largely of what this electronic nervous system transmits to us. The mass media have become our common ground with countless other groups that make up the national and international community. The mass media thus bring together audiences that would previously have lived in separate worlds. Never before have all social classes, groups, and ages shared so much of the same cultural fare, while having so little to do with its creation.

There is more that makes the modern mass media different from the culture of past centuries. Today’s mass media are not only centralized and remote from their audiences, they are also overwhelmingly commercial enterprises, in the business of buying and selling products—and their primary product is audiences. The selling to advertisers of our presumed attention is the transaction at the heart of the mass media economy in the United States and, increasingly, throughout the world.

The media have learned that they can attract our attention most effectively when they tempt us with enjoyable, amusing, engrossing images, songs, and stories. As a society we have become addicted to one of the most powerful drugs known to our species: entertainment. We consume entertainment in astounding amounts and varieties. Some numbers:

• In 1996 the music recording industry sold just over a billion albums, and the 10 to 34 age group accounted for about 65 percent of these purchases.

• After a post-TV falloff, radio listening was back to 3.25 hours by 1981. In 1997 there were more than 12,000 radio stations in the United States (most, however, owned by a small number of major media corporations).

• In the late 1990s about 420 movies appeared on the screens of more than 25,000 theaters, and Americans bought about 1.3 billion movie tickets per year (nearly half of these bought by 12–29-year-olds, who represent about 30 percent of the population).

• Daily television viewing per household has risen steadily from four and one half hours in 1950, when only few had TVs, to more than seven hours since the early 1980s, when nearly everyone had at least one. By 1986, 57 percent of U.S. households had two or more TVs; in 1999, 64 percent of American teenagers had TV sets in their rooms.

• When we watch television we are watching more than programs: the average television viewer sees more than 38,000 commercials every year.

All human societies have created, shared, and consumed with pleasure the symbolic products we can collectively call “culture” or “the arts.” The very processes through which all human societies create and maintain themselves—that distinguish us from our animal ancestors—are those of story-telling in words, pictures, music, and dance. For most of human history the stories, songs, and images people knew were crafted by members of their own communities, with whom they shared the basic conditions of life. In stark contrast to preindustrial societies, in which the culture communities consumed was almost entirely dependent on what they could produce, we now are faced with endless competing choices, twenty-four hours a day, produced by industrial corporations with which we have no social contact whatever.

Remember: this dizzying array of media options is not there because anyone actually asked for all these images, songs, or stories. Rather, it exists because someone, somewhere, has a commercial interest in selling us a product—or more typically, in attracting our attention so that it can be “sold” to advertisers who wish to sell us something. While major corporations compete to spend hundreds of thousands of dollars to place a thirty-second ad during the Super Bowl halftime, there are usually small businesses eager to spend much lower sums to place their ads during late-night programs or on less popular cable channels. Whether larger or smaller audiences, in prime time or less desirable demographics, the media are selling audience attention all the time, on all channels.1

The businesses that manufacture and distribute media fare are increasingly interconnected, and this helps them coordinate their efforts in packaging and selling their products. While they seem on the surface to be separate and independent enterprises, we might wonder what happens when three of the five top-selling magazines in the country (People, Time, Sports Illustrated) are owned by the same company, Time Warner, which also owns major record producing and book publishing companies, as well as CNN and HBO (and that ended the century by merging with the Internet service AOL). Should we be surprised when the stars of Warner Brothers movies, or singers who record for Warner Records, are featured on the cover of People or Time, or profiled on CNN? No more than we should wonder why morning or late-night talk shows on the networks seem endlessly interested in guests who happen to have “specials” on those same networks that same week.

The corporations that create media fare also control how particular social groups and issues are represented. Indeed, representation in the media is in itself a kind of power, and thus media invisibility helps maintain the powerlessness of groups at the bottom of the social heap. Not all interests or viewpoints are treated equally, and judgments are routinely made—by producers and writers, editors and reporters—about what to include or exclude. Sometimes these decisions are enforced by official rules: for example, the Federal Communications Commission once listed “seven dirty words” that could not be spoken on the air;2 likewise, the Motion Picture Production Code in force from the 1930s through the early 1960s required that crime must never pay and that homosexuality was the love that dare not speak its name.

Whatever the motives of preindustrial storytellers, in our commercial media those who determine the content of our news and entertainment programming live and die by the bottom line. In such circumstances, their decisions are inevitably weighted toward the safe and predictable, toward formulas that have worked in the past, and their goal is to attract the largest possible audience of individuals whose spending power appeals to potential advertisers (which presently means younger audiences for the most part). Under these conditions, it is far safer to repeat previous successes—in the form of sequels, spin-offs, and imitations—than to introduce innovations that push the envelope too far or too quickly.

When previously ignored groups or perspectives do gain visibility, the manner of their representation will reflect the biases and interests of those powerful people who define the public agenda. And these are mostly white, mostly middle-aged, mostly male, mostly middle and upper-middle class, and overwhelmingly heterosexual (at least in public).3 As of the late 1990s, the television networks and major film studios, with almost no exceptions, are all run by men who fit this profile. While a woman has occasionally broken into the white boys’ club of the studio complex, she rarely lasts long at the top.4 In a closed world of writers, directors, producers, and so on, who read, watch, and listen to the same media, we can only expect that shared assumptions would be reinforced. The images of women and minorities that do appear on the country’s big and little screens will be those that make sense to those who have decision-making power—the images that fit their own worldview or that have succeeded in the past.

Hollywood’s calculus of casting risks and benefits is shifting, however, partially in response to societal changes and partially in tandem with advertisers’ perceptions of the changing values of the “prime demographic” young audiences they crave. These shifts have eased the restrictions of lesbian and gays who work in the entertainment industries, while having little impact on people of color. The lineup of new TV series for fall 1999 included no African American leads among them. When the NAACP protested what it termed a “virtual whitewash,” TV producer Marshall Herskovitz commented, “The overwhelming majority of TV executives and producers are white, so their concerns generally follow their own lives.”5 At the same time, the fall 1999 lineup forecast seventeen gay characters, about the same as the number of African American, Asian, and Latino characters combined. The Los Angeles Times noted that there are gays on television because there are gays in television. “Unlike Latinos, blacks and Asian Americans, gay people are fully integrated into the Hollywood power structure. They hold jobs from the upper ranks to the lower reaches of the industry, in much the way Jews have traditionally occupied a disproportionate number of positions in the entertainment business.” Yet, as the Times continued, “This is not to say that executives are freely out of the closet and that writers work without constraints, creating fully realized gay characters without fear of reprisal from the network or advertisers. Executives still routinely live semi-closeted lives, and Joe Voci, who produces series with Mandalay Television, notes that although there are gay characters on TV, gay-themed shows—with the exception of Will & Grace—are still nonexistent.”

Print has been with us for 500 years, photography for 150, electricity and telephony for more than a century, movies and automobiles for about 100 years, radio for almost 80 years, and television for half a century. As we all know, the pace of technological innovation has greatly accelerated, and its cumulative impact is transforming the world. What do we know about the impact of television’s first half century? As I have already argued, television now dominates the cultural environment, telling most of the stories to most of the people all of the time.

Unlike print, television does not require literacy. Unlike the movies, television (in the United States) is “free” (supported by a privately imposed tax on all goods) and it is always running. Unlike radio, television can show as well as tell. Unlike the theater, concerts, movies, and even churches, television does not require mobility. It comes into the home and reaches individuals directly. With its virtually unlimited access from cradle to grave, television both precedes reading and, increasingly, preempts it.

Marshall McLuhan’s familiar claim that we live in a “global village” was both insightful and deceptive: he accurately pointed to the homogenization and sharing of common messages that television has brought about, but he falsely equated the sharing of received messages with the mutual interaction and regulation that is characteristic of authentic community.

Television has become the key source of information about the world, creating and maintaining a common set of values and perspectives among its viewers. In fact, given that the average American adult spends several hours each day with television, and children spend even more time immersed in its fictional reality, the media have become central agents of enculturation. Expanding this observation, the Cultural Indicators research project conducted by George Gerbner and myself, along with Michael Morgan and Nancy Signorielli, in the 1970s and 1980s, used the concept of cultivation to describe the resulting influence of television on viewers’ conceptions of social reality. On issue after issue those who watch more television are more likely—whatever their background—to project television’s versions of reality on to their conceptions about the world, its people, and how they function.

We ultimately isolated a pattern that we termed “mainstreaming.” The mainstream can be thought of as a commonality of viewpoints and values that television tends to cultivate in its viewers. While light viewers in any particular demographic group may exhibit relatively divergent positions on a given topic, heavy viewers are more likely to agree with the viewpoint proffered by television. In other words, differences explained by the viewers’ divergent backgrounds and life situations—differences that are readily apparent in the answers given by light viewers—tend to diminish or even disappear when heavy viewers in the same groups are compared. Heavy television use is thus associated with a convergence of outlooks, a mainstreaming of opinion.

Because commercial television seeks large and heterogeneous audiences, its messages are designed to disturb as few as possible. They tend to balance opposing perspectives and steer a course along the supposedly nonideological middle ground. We found that heavy viewers are significantly and substantially more likely to label themselves as “moderate” rather than either “liberal” or “conservative.” Thus, on the surface, mainstreaming appears to be a centering of political and other attitudes. However, a look at the actual positions taken in response to questions about a number of political issues shows that the mainstream does not always mean middle of the road. When we analyzed responses by samples of American adults to questions on social issues that have traditionally divided liberals and conservatives, we found such a division mainly among those who watch little television. Overall, self-styled moderates are closer to conservatives than they are to liberals. Among heavier viewers of television, liberals and conservatives are closer to each other (often statistically indistinguishable) than among lighter viewers. In most cases, this is due to the virtual collapse of the typical liberal opinion among heavy-viewing liberals.

We have identified the mainstream as the embodiment of a dominant ideology, cultivated through the repetition of stable patterns and absorbed by otherwise diverse segments of the population. Yet it nevertheless has to contend with the possibility of oppositional perspectives and interpretations. What options and opportunities are available to those groups whose concerns, values, and even very existence are belittled, subverted, and denied by the mainstream? Can the power of the mass media’s centralizing tendencies be resisted, can one avoid being swept into the mainstream?6 The answers to such questions depend in large part on the group; while many segments and perspectives are similarly ignored or distorted by the mass media, not all have the same options for resistance, or the development of alternative channels.

In general the opportunities for organized opposition are greatest when a visible group can create and disseminate alternative messages. Numerous settlements have sprung up, as it were, along the right bank of the mainstream. Most organized and visible among these are the Christian fundamentalist cable television programs. These programs provide their (generally older and less educated) viewers with an array of programs, from news to talk shows to soap operas to church services and sermons, all reflecting perspectives and values that they quite correctly feel are not represented in mainstream, prime-time television or in the movies.

The religious sponsoring and producing organizations are not merely engaged in meeting their audiences’ previously unmet needs for a symbolic environment in which they feel at home. They are also attempting to translate the (usually exaggerated) numbers of their audiences and their (constantly solicited) financial contributions into a power base from which they can exert pressure to alter the channel of the mainstream and bring it even closer to where they now reside, up on the right bank.

At the moment, and for the foreseeable future in the United States, at least, there is no comparable settlement on the left bank of the mainstream. Right-wing minority perspectives are ultimately supportive of the dominant ideology, however much the media’s need for massive audiences might sacrifice or offend their interests. Minority positions and interests that present radical challenges to the established order will not only be ignored, they will be discredited.

Those who benefit from the status quo present their position as the moderate center, balanced between equal and opposing “extremes”—thus the U.S. news media’s cult of “objectivity,” achieved through a “balance” that reflects an invisible, taken-for-granted ideology. The fatal flaw in the credo of centrism is that how one defines the “responsible” extremes determines where the center will be. In the United States the mass media grant legitimacy to positions a lot further to the right than to the left, which puts the “objectively balanced” mainstream clearly to the right of center. Jesse Helms can be elected and reelected to the Senate, while his opposite number on the left, whoever that might be, couldn’t conceivably claim or receive that degree of visibility, power, and legitimacy. Yet in the final analysis, the “legitimate” left and right both serve to buttress the ramparts of the status quo, and to keep the truly oppositional from being taken seriously.

In its early days, television in the United States brought entire communities “together” to absorb common messages, but the assembly was symbolic rather than physical. Americans watched television from their separate living rooms and were able to discuss their common media fare the next morning around the water coolers and in the school yards of the nation. When more than two-thirds of the nation watched network programs each night, when even larger proportions watched Lucy, and when astronomically large audiences watched Kennedy’s funeral, the moon landing, the royal wedding, O.J.’s trial, and Princess Diana’s funeral, television was able to bring national and even worldwide communities together, however briefly.

However, developments in recent years in the United States and around the world are changing these patterns. If the first era of television was one of heterogeneous audiences united in watching common programs on few channels, we are now well into the era of multichannel programming aimed at ever narrower demographic audience slices. Television is beginning to fragment its audiences and its messages, becoming more like print than early broadcasting, and thus we are likely to see changes in its effects. But the experience of the past half century should caution us against premature forecasts of an age of media differentiation that will fragment audiences into narrow coteries, each consuming a distinct and tailored diet. For, certainly, our experience so far has been one of illusory differences that don’t, in fact, make much difference.

While we all know there are distinctions between television advertising and programming (or between ads and articles in newspapers and magazines), we should not overstate these differences, especially in the case of television. News, drama, quiz shows, sports programs, and commercials share many underlying similarities. Even the most widely accepted distinctions—such as those among news programs, drama, and commercials—are easily blurred. In Sarah Kozloff’s nice phrase, “American television is as saturated in narrative as a sponge in a swimming pool. … Forms that are not ostensibly fictional entertainments, but rather have other goals—description, education, persuasion, exhortation, and so on—covertly tend to use narrative as a means to their ends.”

Decisions about which events are newsworthy and about how to present them are guided by considerations of dramatic form and content drawn from fiction. For a story to be “newsworthy” it must contain a break in the usual order of things (a disaster, a murder, a scandal, etc.), followed by plot development and resolution. In 1963 Reuven Frank, executive producer of NBC News (and later president of NBC’s news division), advised journalists that, “Every news story should, without sacrifice of probity or responsibility, display the attributes of fiction, of drama. It should have structure and conflict, problem and denouement, rising action and falling action, a beginning, a middle, and an end.”

The amount of attention devoted to a news story is not necessarily a measure of importance on any “objective” scale, as opposed to its ability to attract and maintain audiences—how else to explain the news media’s fixation on O. J. Simpson’s trial, or the incessant repetition of that image of Monica and Bill embracing? Likewise, the polished minidramas of most commercials reveal a mastery of fictional style. Consider the compressed 30- or 60-second narrative structure of a typical commercial: a problem (dirty laundry, stomach ache, romantic difficulties) leads to plot development (use of the product: detergent, antacid, mouthwash) and the expected happy ending (clean socks, relief, romance).

The arrival of “infomercials” and home-shopping programs on the one hand, and so-called reality-based television, blending staged and documentary footage (such as America’s Most Wanted and Cops), on the other, has made it even more difficult to distinguish between “informing,” entertaining, and selling. Superficially different forms of programming support each other by using similar narrative structures and visual styles and dramatizing identical values of consumerism and the “good life.” Commercials and programs generally look and sound alike, teaching complementary lessons. Programs that fail to reinforce these mainstream values often find themselves unable to attract sponsors and wind up in the vast graveyard of canceled programs.

Programs and commercials also have in common the formal conventions of realism. That is, despite a limited degree of reflexivity—in which a program deliberately calls attention to its own artificiality (say, when the cameras pull back at the end of a sketch on Saturday Night Live to reveal the set surrounded by the larger sound stage)—mainstream films and television programs are presented as transparent windows on reality that show us how people and places look, and how institutions operate—in short, supposedly the “way it is.” But even “backstage” dramas about the media, such as Murphy Brown and Frasier, are highly unrealistic and conform thoroughly to the contours of other network fare. Nonetheless, for many viewers such programs may constitute their only source of information about the inner workings of a newsroom or radio station.

These depictions of the way things work are personified through characterizations and dramatized through plots that take us into situations and places we might otherwise never see. They show us the hidden workings of personal motivation, organizational performance, and subcultural life. Normal viewers, to be sure, are aware of the fictiveness of media drama; no one calls the police when a character on TV is shot. But how often and to what extent do viewers actually overcome the media’s seductive realism? In truth, even the most sophisticated among us can find many components of our “knowledge” that derive wholly or in part from fictional representations. How many of us have been in an operating room—awake—or in a courtroom during a murder trial? How many have been in a jail or a corporate boardroom? Yet we all possess images of and information about such places that is patched together from our experience with dramatic and news media. Through the media we have witnessed open-heart surgery, murder trials, jail riots, and high-level corporate deliberations. Are these images accurate? Most of us will never know, because our experiences are likely to be limited to what the media choose to show and tell us.

Thus, the media are likely to be most powerful in cultivating images of events and groups about which we have little firsthand opportunity for learning. By definition, most minority groups and “deviants” of various sorts will fall into the category of being relatively distant from the lives and daily experiences of those who are not members of a given minority group or “deviant” category. Lacking other sources of information, most people accept even the most inaccurate or derogatory information about a particular group or event.

Most mediated images reflect the experiences and interests of the majority groups in our society, particularly those who constitute the large audiences producers wish to sell to advertisers. A group of researchers examined fifty-six sitcoms and drama shows aired on ABC, CBS, NBC, and FOX between October 28 and November 3, 1991, and concluded that “characters on prime-time dramas and situation comedies are mostly male, white, single, heterosexual, in their 30’s or 40’s, and work in professional, managerial, or semi-professional, middle to high income jobs.”

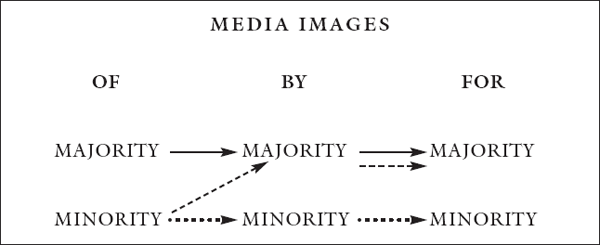

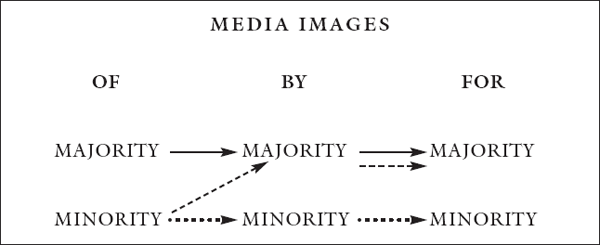

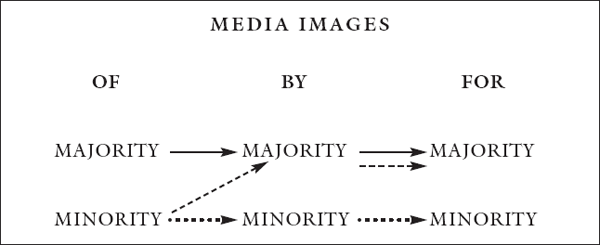

Figure 1 (suggested by sociologist Elihu Katz) shows the patterns of media images of majority and minority groups: the solid line represents the vast preponderance of programming that depicts majority images as produced by and for the majority group; the broken line represents a much smaller proportion of programming that focuses on minorities, but this too is produced by, and largely for, members of the majority group. The dotted line represents the smallest portion of media content—programming produced by and for minorities.

The term minority has been applied to ethnically and racially defined people as well as to women (in terms of their relative powerlessness despite their numerical superiority), and it is now commonly applied to lesbian women and gay men. All of these categories are defined by their deviation from a norm that is white, male, Christian, and heterosexual, and these deviations are reflected in the mirrors that the media hold up before our eyes. In brief, minorities share a common media fate of relative invisibility and demeaning stereotypes. But there are differences as well as similarities in the ways various minorities are treated by the mass media. And because there are important differences in the conditions they face in our society, the effects of their media images are different for members of the various minority groups.

Unlike women, who might be viewed as minority spectators of images produced by and for male audiences, more “conventional” minorities have difficulty even finding their images reflected on the big and small screens of our mainstream media. The heterosexual male might be the center of everyone’s (certainly of his) dramatic universe, but he will also be provided with appropriate female companionship (the spoils of the victor, one might say). Conversely, there is no demand for—and much resistance to—the frequent appearance of figures marked by their difference from the white, middle-class, Christian (if secular), heterosexual norm. Minority audiences facing their living room “window on the world” have had to make do with sparse fare. African American scholar Patricia Turner, reflecting back on her childhood in the 1950s and 1960s, recalled that, “While my mother loathed making long distance calls, even when there was a death in the family, she would call long distance to share news that a ‘Negro’ was scheduled to appear on a television program. … Our images were few and far between, and we hungered for more of them.”

In a similar vein, Chinese American actor B. D. Wong, commenting on his role (as a Korean American) on the TV sitcom All American Girl, notes: “When we were growing up, when an Asian person came on TV, somebody would say: ‘Come quick! Come into the living room. There’s an Asian person on TV.’ And everybody would run and go, with this bizarre fascination: ‘Oh wow, look at that. That’s amazing.’”

I would venture to suggest, however, that B. D. Wong would not have been called into the living room to witness one of the even more rare appearances of a lesbian or gay character on television. Despite the fact that Wong would have had particular reason to be interested in such appearances, it is highly unlikely that his family would have been aware of this interest, or that they would have indulged it had they suspected. Lesbian and gay people do not share the sort of fond recollections recounted by Turner or Wong.7

Sexual minorities differ in important ways from the “traditional” racial and ethnic minorities; in many ways we are more like “fringe” political or religious groups. Like other social groups defined by forbidden thoughts or deeds, we are rarely born into minority communities in which parents or siblings share our minority status. Rather, lesbians and gay men are a self-identified minority and generally only recognize or announce our status at adolescence, or later. Also, by their very existence, sexual and political minorities constitute a presumed threat to the “natural” (sexual and/or political) order of things, and thus we are always seen as controversial by the mass media. Being defined as controversial invariably limits the ways lesbians and gay men—or political and religious “deviants”—are depicted in the media on the rare occasions when they do appear. It also shapes the effects of such depictions on the images held by society at large and by members of these minority groups.

Close to the heart of our cultural and political system is the pattern of roles associated with sexual identity: our conceptions of masculinity and femininity, of the “normal” and “natural” attributes and responsibilities of men and women. And as with other pillars of our moral order, these definitions of what is normal and natural support the existing social structure. The maintenance of the “normal” gender-role system requires that children learn—and adults be discouraged from toppling—a set of expectations that channel their beliefs about what is possible and proper for men and for women.

The gender system is supported, in turn, by the mass media’s treatment of sexual minorities. Lesbians and gay men are usually ignored altogether; but when they do appear, it is in roles that support the “natural” order and they are thus narrowly drawn. The stereotypic images are always present, if only implicitly, as when gay characters are depicted in a carefully “antistereotypic” manner that draws our attention to the absence of the “expected” attributes. Richard Dyer has pointed out that, “What is wrong about these stereotypes is not that they are inaccurate.” They are, after all, often more than a little accurate, at least for some gay people, some of the time. Dyer continued, “What we should be attacking in stereotypes is the attempt of heterosexual society to define us for ourselves, in terms that inevitably fall short of the ‘ideal’ of heterosexual society (that is, taken to be the norm of being human), and to pass this definition off as necessary and natural.” Sexual minorities are not, of course, unique in this regard—one could say the same for most media images of minorities. But our general invisibility makes us especially vulnerable to the power of media images.

Of all social groups, we are among the least permitted to speak for ourselves in public life, including in the mass media. Prior to Ellen Morgan’s much publicized coming out (along with her real-life counterpart, Ellen DeGeneres) in 1997, and the following year’s Will Truman of NBC’s Will & Grace, no major network television program had a lesbian or gay lead character. Gay roles are no longer scorned as the kiss of death for movie stars—after all, both William Hurt and Tom Hanks won Oscars for playing gay men—but there is still not a single openly lesbian or gay major Hollywood star. This is not exactly a matter of personal choice. The entire industry operates on the principle that the American public is suffused by prejudices that must be catered to. In earlier decades the same logic required Jewish actors to submerge and hide their ethnicity. “In Hollywood, stars assumed neutral names like Fairbanks, or Howard, or Shaw; actresses underwent plastic surgery; some made a point of going to Christian churches or donating money to Christian charities.”

Openly lesbian and gay reporters are absent from the news programs inhabited by the likes of Tom Brokaw, Carole Simpson, or Connie Chung. While we are certainly present in the story conferences and newsrooms in which such programs are assembled, it is generally on condition that we keep our identities hidden, from the audience if not always from our colleagues.

We are also the group whose enemies are generally least inhibited by the consensus of “good taste” that protects other minorities from the more public displays of bigotry. It is unthinkable in the 1990s that any racial or ethnic minority would be subjected to the sort of rhetorical attack that is routinely aimed at lesbian and gay people by public figures, who do not encounter widespread condemnation for their bigotry. When Roberta Achtenberg, a member of San Francisco’s Board of Supervisors and a prominent legal activist, was nominated by President Clinton in 1993 as Under Secretary of Housing and Urban Development, Sen. Jesse Helms (R-NC) went on the attack: “She’s a damn lesbian … working her whole career to advance the homosexual agenda. Call it gay-bashing if you want to. I call it standing up for traditional family values.” One would have to go back decades to find such unabashed bigotry directed against a member of a racial or ethnic minority on the floor of the U.S. Senate.8

Our vulnerability to media stereotyping and political attack derives in large part from our isolation and pervasive invisibility. The process of identity formation for lesbian and gay people requires the strength and determination to swim against the cultural stream one is immersed in at birth. A baby is born and immediately classified in two critical dimensions. One is presumed to be known before birth—when a baby is born no one asks, “What race is it?”—because we believe in a rigid set of racial identities (and, in our white supremacist society, if you’re not “all white” you’re “not white”). The other identifying attribute is the subject of that familiar first question: boy or girl? The newborn infant is held up, inspected, and wrapped in an appropriately colored blanket. As we know, the blue-blanket babies and the pink-blanket babies are treated differently from that moment on, by doctors and nurses and parents and everyone else. Something else is taken for granted at the same time that also affects how that baby is treated: it is defined as heterosexual. It is made clear throughout childhood that this baby is expected to grow up, marry, have children, and live in nuclear familial bliss, sanctified by religion and licensed by the state. Over and over, through a multitude of messages in a myriad of media, that child encounters the taken-for-granted assumption that his or her future is heterosexual.

How do those of us who are not white, male, middle class, Christian, and heterosexual come to a sense of identity and self-worth in a society that values attributes we do not and mostly cannot possess? Well, for one thing, we can observe the people around us as well as those we encounter through the lens of the media. Women are surrounded by other women, African Americans by other African Americans, and so forth, and can observe the variety of choices and fates facing those who are like them. Mass media may offer only a narrow range of roles and images for women and minorities, but their biases and omissions are also balanced by the audiences’ own experiences.

In contrast, lesbians and gay men are a self-identifying minority. We are presumed to be straight, and are treated as such, until we begin to recognize that we are not what we have been told, that we are different. But how are we to understand and deal with that difference? We generally have little to go on beyond very limited direct experience with those individuals who are sufficiently close to the accepted stereotypes to be labeled publicly as queers, faggots, dykes, and so on. Increasingly, openly lesbian and gay people are present throughout society, but even so, nearly half of the people surveyed in polls say they know no gay people, and large majorities say there are none in their family. And we have the mass media. In the absence of adequate information in their immediate environment, most people—gay or straight—have little choice but to accept the media stereotypes they imagine must be typical of all lesbians and gay men.

The rules of the mass media game have had a double impact on gay people: not only have they mostly shown them as weak and silly, or evil and corrupt, but they continue for the most part to exclude and deny the existence of normal, unexceptional as well as exceptional lesbians and gay men. Hardly ever shown in the media are just plain gay folks, used in roles that do not center on their difference as an anomaly that must be explained, a disappointment that might be tolerated, or a threat to the moral order that must be countered through ridicule or physical violence. The stereotypic depiction of lesbians and gay men as abnormal, and the suppression of positive or even “unexceptional” portrayals serves to maintain and police the boundaries of the moral order. It encourages the majority to stay on their gender-defined reservation, and tries to keep the minority quietly hidden out of sight. For the visible presence of healthy, unapologetic lesbians and gay men does pose a serious threat: it undermines the unquestioned normalcy of the status quo, and it opens up the possibility of making choices that people might never have otherwise considered could be made.9

We are all colonized to some degree by the majority culture. Those of us who belong to one minority group or another will inevitably have absorbed many mainstream values, even when they serve only to demean us. Similarly, although it might seem contrary to their interests, millions of nonwhites across the globe happily consume U.S. media products, with their distinctly “white-angled” view of the world. Recognizing these patterns is a first step toward demanding more even-handed media representation of all cultural groups. Yet this does not, in itself, guarantee a solution.

In the case of sexual minorities, there have been responses to the media’s hostile treatment of sexual minorities that represent degrees of subversion and resistance. Sexual minorities are particularly vulnerable to the internalization of mainstream values, given that the process of self-identification generally occurs in isolation and relatively late in life. As gay liberationist writers Hodges and Hutter put it: “We learn to loathe homosexuality before it becomes necessary to acknowledge our own. … Never having been offered positive attitudes to homosexuality, we inevitably adopt negative ones, and it is from these that all our values flow.” Without realizing it, even lesbians and gay men may be profoundly heterosexist in their thinking and outward behavior.

Individuals who internalize or fail to challenge mainstream beliefs often do not realize, however, that by defending antigay and antilesbian values, they are essentially doing the work of their oppressors. Political theorists use the term hegemony to describe this sort of collusion between master and slave, in which the oppressed are somehow persuaded that their oppression is just, inevitable, or natural. Once a hegemonic system is in place, those at the top of the hierarchy need only defend the ideologies and structures that convince those below that they belong there. Once homosexuals believe that they are in fact perverted, trivial, or unworthy of public recognition—and therefore lack the grounds to protest their mistreatment—their oppressors’ work has been done for them. The Zionist polemicist Ahad Ha-’Am drew on a biblical analogy, in an essay on Moses, to describe this phenomenon: “Pharoah is gone, but his work remains; the master has ceased to be master, but the slaves have not ceased to be slaves.” And as Raymond Williams pointed out, hegemony “is never either total or exclusive. At any time, alternative or directly oppositional politics and culture exist as significant elements in the society.” One such oppositional strategy is the appropriation and subversion of mainstream media.

For gay males, the classic strategy of subversion is camp—an ironic stance toward the straight world rooted in a gay sensibility. As British gay writer Jack Babuscio defined it, camp reflects “a consciousness that is different from the mainstream; a heightened awareness of certain human complications of feeling that spring from the fact of social oppression; in short, a perception of the world which is coloured, shaped, directed and defined by the fact of one’s gayness.” This characterization would, of course, fit the comic or aesthetic styles of other oppressed groups (e.g., the fatalism of Jewish humor, the sense of loss in African American folk songs that gave rise to the blues), but the gay sensibility differs in that we encounter and develop it at a later stage in life; it is nobody’s native tongue.

Moreover, while sharing much with other minority perspectives, camp is suffused with a theatrical view on the world that is rooted in the particular realities of lesbian and gay life. Forced to “pass for straight” in order to avoid social stigma or physical danger, one develops, Babuscio noted, “a heightened awareness and appreciation for disguise, impersonation, the projection of personality, and the distinctions to be made between instinctive and theatrical behaviour.” In short, the gay sensibility incorporates a self-conscious role-playing and theatricality—and the knowledge that social and gender roles are ultimately no more than performances, arbitrary guises into which skilled players can step at will. Passing for straight involves play-acting, pretending to be something one is not, either by projecting untruths or withholding truths about ourselves that would lead others to the (correct) conclusion about our sexuality.

Rooted in this sensibility, camp serves several purposes. It supplies an opportunity to express distance from and disdain for mainstream culture. Exchanged in private settings, camp helps forge in-group solidarity, repairing some of the damage inflicted by the majority and preparing us for further onslaughts. Used as a secret code in public settings, it can also be a way to identify and communicate with other “club members” under the unknowing eyes of the straight world—itself an act of subversive solidarity. Politically, it can also be a form of public defiance, a flamboyant expression of sexual variation that dares to show its face. Finally, camp is the quintessential gay strategy for undermining the hegemony of mainstream media images. The sting can be taken out of oppressive characterizations and the hot-air balloons of conventional morality can be burst with the weapon of irony. Most importantly, by encouraging viewers or readers to evaluate mainstream culture as outsiders, as spectators living beyond its perimeter, a camp sensibility creates a sense of detachment from the dominant ideology. In the words of Richard Dyer:

The sense of being different … made me feel myself as “outside” the mainstream in fundamental ways—and this does give you a kind of knowledge of the mainstream you cannot have if you are immersed in it. I do not necessarily mean a truer perspective, so much as an awareness of the mainstream as a mainstream, and not just the way everything and everybody inevitably are; in other words, it denaturalizes normality. This knowledge is the foundation of camp.

Ultimately, the most effective form of resistance to the hegemony of the mainstream is to speak for oneself, to create narratives and images that counter the accepted, oppressive, or inaccurate ones. While many groups and interests are ignored or distorted in the media, not all have the same options for resistance. The opportunities for opposition are greatest when there is a visible and organized group that can provide solidarity and institutional support for the production and distribution of alternative messages.

In post-World War II America, lesbian women and gay men began, with difficulty, to create alternative channels of communication that would foster solidarity and cultivate the emergence of a self-conscious community. Typically, the first alternative channels to appear are those with low entry barriers, minimal technological needs, and relatively low operating costs. Thus, newspapers and magazines have long been the principal media created and consumed by minority groups.10 In recent decades, video technology has made it possible for anyone with a camera and editing deck (or at least access to them) to produce fictional and nonfiction programs. But the problem of distribution remains a major hurdle (although video technology makes possible syndicated cable programs). Films, while far more expensive to make, can often recoup their investment by identifying and appealing to a relatively specific niche. Finally, the Internet now utilizes a relatively cheap technology to provide Web-based news and magazine sites, chat rooms, bulletin boards, and mail networks. By contrast, it is network television—with its numerous regulatory hurdles, high production costs, and demand for broad audiences—that remains the most insular and undemocratic of the media, largely unavailable to most minority groups.