I

PROFILES

ATTARDI, ALPHONSO

499 East Eleventh Street, 14 East Twenty-third Street

Alias: Altroad DeJohn, Jim Carra[?]

Born: 1897,3 Porto Empedocle, Sicily

Died: 1972, Suffolk County, New York

Association: D’Aquila, Mangano/Gambino crime families

Many of those in the know believe this five-foot, four-inch, 160-pound veteran mobster turned informant was the same person who shared his life story with veteran journalist Jack Anderson in the late 1960s under the name Jim Carra.

In a widely redistributed January 28, 1968 article published by Parade Magazine, entitled “A Top Killer Spills Mob Secrets,” a former mobster with a curiously similar background to Attardi’s provided intimate details of everything from the protocols of a Mafia initiation ceremony to the murder of Albert Anastasia.

Unlike Joe Valachi, whose testimony offered a wealth of information but yielded few arrests, the information Attardi provided to authorities in the 1950s led to a massive infiltration of organized crime that resulted in several convictions. Also unlike Valachi, who has become a household name to even the most casual mob enthusiast, very little has been written about (or even reported on) Attardi.

Let’s start with what we do know from released government files and the few news reports available on the elusive gangster. In 1922, Attardi served a four-month sentence for the violation of the Harrison Act, which was passed in 1914 “to impose a special tax on all persons who produce, import, manufacture, compound, deal in, dispense, sell, distribute, or give away opium or coca leaves, their salts, derivatives, or preparations.”

A January 15, 1947 internal memo from the Federal Bureau of Narcotics (FBN) field office in New York City claimed that Attardi admitted to attending a 1937 meeting on the outskirts of Houston, Texas, on the farm of Don Vincenzo Vallone. (To whom he admitted this detail is recorded as “unknown.”) In attendance, according to the report, was Dallas mob boss Joseph T. Piranio and underboss Joseph F. Civello.

The reason for the meeting is unknown, though we do know that on October 5, 1937, Attardi; his wife, Josephine “Jose” Attardi, alias “G. Altroad”; and fourteen others were swept up in a coordinated interstate roundup, suspected of conspiring to import narcotics from Europe and distribute them through New York, Texas and Louisiana.

Alphonso Attardi was held in the Galveston County (Texas) Jail until posting $10,000 bond on December 14, 1937. On January 31, 1938, he and his wife were extradited back to New York City, where sixteen of the eighty-eight people named in the indictment were brought to trial in May 1938. Several opted to plead guilty in lieu of facing a jury. At least two witnesses testified to delivering drugs for Attardi from a Galveston nightclub called Turf. On June 2, 1938, Alphonso Attardi was sentenced to two years in Leavenworth, plus a $5,000 fine.4 His wife received two years plus a $1,000 fine, though that was later reduced to five years’ probation.

On May 9, 1950, the FBN headquarters in Washington, D.C., furnished a list of twenty-four Mafia suspects operating in Texas. Among the names on record were New York Mafioso Vito Genovese and Vincent Rao; Attardi was listed as operating in Houston.

Other than that, only two authors that I know of have mentioned Attardi. According to 1963’s Border Guard: The Story of the United States Customs Service by Don Whitehead, Attardi spent eight years in the 1940s behind bars on narcotics violations and faced deportation to Italy upon release.

The author goes on to say that Attardi fell in love with a twenty-two-year-old waitress and feared deportation, so he offered himself up to federal authorities. By 1952, Attardi was working with the FBN to set up several successful undercover sting operations, for which he received a paltry $5,000 and disappeared with his new lover.

In The Great Pictorial History of World Crime (volume one, published in 2004), author Jay Robert Nash adds that Attardi’s 1940s conviction was a “bum rap” and that while he was in prison, Attardi’s wife passed away and he lost his oil and cheese importing store on Chrystie Street.5

Beyond that, the trail pretty much dries up for Alphonso Attardi. If we are to believe the 1968 claims of Jim Carra, who was admittedly speaking in anonymity under an assumed name, the gangster was initiated into a Sicilian Mafia organization as a teenager before immigrating to New York City in 1919. Here, he started as a bootlegger working for the D’Aquila crime family in the 1920s and went on to watch the Mafia evolve in its most formative years.

“The honor, respect and morality that had been instilled into me in Sicily all became secondary matters. The big thing in the United States was money and more money,” Carra recalled, disenchanted with the greed that polarized the Italian underworld during Prohibition.

BIONDO, JOSEPH

245 East Twenty-first Street, Manhattan, 1930

Alias: Joe Bandy, Joe the Blonde

Born: April 16, 1897, Barcellona Pozzo di Gotto, Sicily (b. Biondi, Giuseppe)

Died: June 10, 1966, New York City

Association: D’Aquila family, Gambino crime family underboss

Biondo was a veteran gangster of the bootlegging wars with an influential criminal career spanning four decades. It is believed that Biondo was involved in the plot to kill both Salvatore Maranzano in 1931 and Albert Anastasia in 1957. He was a perpetual member of Interpol’s International List of Narcotics Violators6 and alleged overseer of the Mangano/Anastasia family drug-trafficking operations throughout the early 1950s.

Around the East Village—the neighborhood where Biondo spent much of his life after emigrating from Italy as a baby in 1898—he was mostly known as “Bandy,” but with a thick Lower East Side accent, it came out almost as “bain-tee.” Some insiders from the old neighborhood had no idea it was spelled with a “D” until seeing it in print later on.

The five-foot-four, 150-pound gangster wielded great influence over younger neighborhood toughs and befriended early on future top-level Mafioso like Charlie Luciano, who claimed to have pickpocketed immigrants while living with Biondo on Fourteenth Street as a kid. The two would be close for the rest of their lives.

On July 4, 1931, Biondo, Luciano and Tommy Lucchese were apprehended together in a Cleveland hotel room and questioned during a police investigation; however, no charges were filed. They were in Ohio to watch Max Schmeling defend the heavyweight title against W.L. Stribling. (Schmeling won by KO in the fifteenth round).

One theory suggests that sometime in 1931, Biondo was visited by Frank Scalise, the newly installed boss of what would become the Gambino crime family. Capo di tuti capi Salvatore Maranzano awarded Scalise the position after the Castellammarese War of 1930–31, allegedly with the stipulation that he must help kill another family boss named Vincent Mangano. Scalise couldn’t go through with the murder and went to Biondo about the plan. Biondo then alerted Mangano, Luciano and others. Maranzano was dead by the end of the year.

In the spring of 1942, Biondo quite openly visited exiled Charlie Luciano in Italy and, as expected, was picked up by authorities in Milano and questioned. Biondo insisted he was in Italy for legitimate business on behalf of major corporations back in the States; however, these companies denied knowing Biondo. No evidence could be found of wrongdoing at the time, but it is believed that Luciano introduced Biondo to a third-party supplier of acetic acid, used to cut heroin for street sale. Biondo made several trips to see Luciano over the years, some believe to deliver Luciano his financial share of various rackets going on back in North America.

In October 1958, the FBN intercepted a letter intended for Biondo from fellow Mafioso Nicola Gentile that read, in part, “The road you have taken by virtue of your intelligence has brought you to a superior social level so that today you are a LEADER and well regarded.”7

Undercover authorities then posed as representatives of Biondo and met with Gentile, fooling him into providing delicate information. When the narcotics agents unveiled their true identities, Gentile decided to testify against the Mafia.

Joe Valachi claimed that Biondi was involved with Carlo Gambino in the 1957 murder of Albert Anastasia, which earned the capo a spot as underboss to Gambino (who replaced Anastasia as head of the family). He also claimed that Biondo was a member of the Mafia Commission.

An internal FBI memo dated October 3, 1967, states that a source claimed Biondo fell out of favor with Carlo Gambino for his chronic participation in narcotics trafficking and even went so far as to say that Gambino ordered a hit on Biondo by the end of 1965. By that time, Biondo was spending much of his time with his New York City–born wife, Louise Volpe (whom he married in 1925), at their second home at 1936 South Ocean Drive in Hallandale, near Miami Beach, Florida.

Joseph Biondo died in 1966 and was succeeded as underboss of the Gambino family by Aniello Dellacroce. His brother, John Joseph Biondo, was an alleged soldier in the Gambino family at the time of Joseph’s death.

BUIA, ANGELO ANTHONY

719 Lexington Avenue, 1950s

Alias: Frenchie, Angelo Russo

Born: July 26, 1910, Nice, France

Died: May 3, 2003, Montgomery, Maryland

Association: Genovese crime family

French-born to Sicilian parents, Angelo Anthony Buia and his brother, Matildo, were considered by the FBN to be major heroin distributors for the Accardi-Campisi crew of the Genovese family.

In August 1955, Buia pleaded guilty to possession of thirty-five ounces of heroin. When a previous conviction for narcotics violations was disclosed, he was sentenced to seven years in prison as a second offender.8

In August 1962, Buia and five other mobsters, including Benedetto Cinquegrana and Carmine Locascio, pleaded not guilty to charges of operating an international drug ring suspected of smuggling over $100 million worth of heroin into the United States over a ten-year period.9 Authorities believed Buia obtained massive amounts of heroin from French sources for three of five Mafia families in New York.10

In December 1963, eleven of sixteen indicted New York mobsters were sentenced to seven to twenty-five years in prison; however, all charges were reversed in August 1964 by an appeals court judge.

BUIA, MATILDO

203 Prince Street, Manhattan, 1950s

Alias: Ralph Stella

Born: October 18, 1907, Castellammare, Sicily

Died: November 23, 1988, New York City

Association: Genovese crime family

Along with his brother Angelo, Matildo was suspected of being involved in international narcotics trafficking for over two decades during the mid-twentieth century.

Matildo’s first arrest on narcotics violations came in 1933, with another conviction in 1938. On August 3, 1955, Matildo and Angelo Buia were arrested for trying to sell approximately thirty-five ounces of heroin to undercover narcotics agents. Matildo was sentenced to five years in prison11 and was released under probation on April 5, 1959.

CATALDO, JOSEPH

125 Sullivan Street, 1920, 1930; 59 West Twelfth Street, 1950s

Alias: Joe the Wop

Born: November 16, 1908, Basilicata, Italy (b. Cataldo, Giuseppe)

Died: July 1980, New York City

Association: Most prominent twentieth-century mobsters

Perhaps most infamous for his alleged ties to Lee Harvey Oswald assassin Jack Ruby, Cataldo was a major twentieth-century mobster, racketeer, loan shark, casino manager, nightclub owner and entertainment industry mover and shaker.

Eight-year-old Cataldo arrived in New York City with his family on November 27, 1916, on the steamship Duca d’Aosta and earned his status as a U.S. citizen in September 1933. Not much is recorded about his initiation into organized crime or his early career with the mob, though it has been implied that his foray into crime began during Prohibition.

125 Sullivan Street today. Courtesy of Sachiko Akama.

According to the Wop himself, he managed a Havana, Cuba casino “in the good old days.”12 By the end of the 1950s, Cataldo operated several wildly popular and successful nightclubs and restaurants in New York City, like Chandler’s, the Camelot Supper Club and Tony Pastor’s. (He is also said to have been tied to the famous jazz club Birdland.)13 The Camelot became the unofficial headquarters for powerful star-broker George Wood of the William Morris Agency, the man responsible for the careers of superstars like Frank Sinatra.14 In 1962, George Wood and Joseph Cataldo partnered in a downtown Vegas casino called Pioneer Club.15

Cataldo gained some national notoriety in 1963 when the FBI traced back to him a phone call thought to have been placed by Jack Ruby on July 7 of that year, just four months before the murder of Oswald. When questioned on December 11, 1963, Cataldo denied knowing Ruby, but an informant told the FBI that Ruby booked “talent”—all of whom turned out to be gangsters—for his Dallas nightclub through Cataldo.

In August 1968, Cataldo and five others were indicted for stock fraud,16 and in February 1980, he was accused of being involved in a plot to disrupt what was known as the “Black Tuna” trial by paying off federal witnesses and assassinating a district court judge. Cataldo died of a heart attack during the trial.

CINQUEGRANA, BENEDETTO

122 Mott Street, 1920; 209 Grand Street, 1930s;

166 Mulberry Street, 1950s

Alias: Benedetto DiPalo, Vincent Grande, ChinkBorn: January 6, 1913,

New York City

Died: August 17, 2002, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey

Association: Genovese crime family

Cinquegrana grew up in the heart of Little Italy, where his butcher father, Luigi, operated a meat market at 156 Mott Street. His parents were married in 1908 in Cesa, Italy (mother Concetta’s hometown), and immigrated to New York City in 1910 with their eldest son, Francesco. Here, they settled at 122 Mott Street, where Benedetto was born in 1913. The future gangster would spend most of his life in his native neighborhood and held interest in several local businesses, like the mob hangout Caffe Roma on Broome Street, where he was listed as vice-president of the corporation. (Fellow wise guy Eli Zeccardi, a future Genovese underboss, was president.)

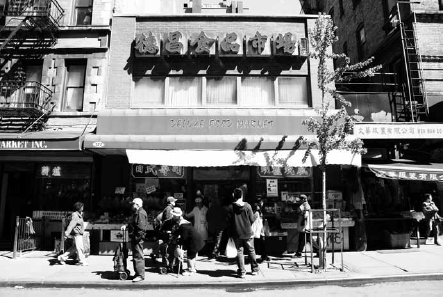

122 Mott Street, the childhood home of Benedetto Cinquegrana, today. Courtesy of Shirley Dluginski.

Convicted of armed robbery by the time he was sixteen years old, Cinquegrana racked up a few arrests for bookmaking in the 1930s and 1940s before turning his attention to narcotics in the 1950s.

Cinquegrana may have earned one of his nicknames because of his associations with Chinese drug smugglers, like Wong Gum Hoy, with whom he was arrested on February 17, 1956, after feds seized from them a half pound of opium.17 In 1962, forty-nine-year-old Benedetto Cinquegrana was one of several men (including Angelo Buia) arraigned as members of an international narcotics ring that was suspected of trafficking tens of millions of dollars’ worth of pure heroin into the country over a nine-year period.18 Charges were dismissed after appeal.

On December 13, 1972, Cinquegrana was called to testify before the Waterfront Commission during an investigation into possible mob racketeering at a Port Elizabeth stevedore company; he pleaded the Fifth and refused to answer any questions.

On December 15, 1981, Cinquegrana did plead guilty to “conspiracy to commit offense or to defraud the United States” and was sentenced to a five-year suspended sentence.19

His last known address was 57 Sherwood Avenue in Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, where he passed away in August 2002 at eighty-nine years old.

CIRAULO, VINCENZO JAMES

88 Second Avenue, Manhattan, 1950s

Alias: Jimmy Second Avenue, Jimmy Ninety-two, Jimmy East, Jimmy Fischetti

Born: September 8, 1919, New York City

Died: September 26, 1997, Palm Beach, Florida

Association: Lucchese crime family

The FBN identified Ciraulo as a “trusted and important member” of a Lucchese crew headed by Carmine Locascio. He operated the Stage Bar on East Fourth Street in the 1950s while living at 88 Second Avenue.

By the 1970s, Ciraulo was a respected Mafia veteran on the lam from New York authorities for outstanding loan-sharking warrants. While a fugitive in Florida, he used the name Jimmy Fischetti and worked closely with Tampa mob boss Santo Trafficante Jr. Ciraulo’s luck ran out when he was arrested by FBI agents on a holiday visit to New York City on January 22, 1980.20 This arrest caused a small rift between the New York and Florida FBI offices, since Ciraulo was at the center of a long sting operation called Coldwater, in which undercover feds established a gambling casino called King’s Court in Pasco County, Florida.

In the summer of 1986, sixty-eight-year-old Ciraulo pleaded guilty to conspiracy and extortion in connection with the Coldwater operation and was sentenced to two years in prison. His codefendant, Santo Trafficante, refused a plea deal and died during a lengthy trial just hours after receiving open heart surgery on March 17, 1987.

Ciraulo died at age seventy-eight while living in Royal Palm Beach, Florida. His funeral was held in the Bronx.

COSTELLO, FRANK

115 Central Park West, Apartment 18F, 1950s

Born: January 26, 1891, Calabria, Italy (b. Castiglia, Francesco)

Died: February 18, 1973, New York City

Association: Luciano/Genovese crime family

Frank Costello was one of the most successful gangsters in U.S. history and partial inspiration behind Marlon Brando’s role in The Godfather. This crime kingpin lived in a luxury building at 115 Central Park West when, on May 2, 1957, he was shot in its lobby by Vincent “Chin” Gigante. He survived but got the message sent by Gigante’s boss, Vito Genovese: it was time to retire.

Born in a small Calabrian village, the young Costello immigrated to New York City in 1900 at about nine years old. He arrived with his mother and older brother, to join their father, Luigi, who had established himself as a small grocery store proprietor in East Harlem before sending for the family back in Italy.

The future criminal icon skipped school and got into trouble early, racking up a slew of petty charges as a youth. He worked for the Morello-Terranova gang in Harlem and made friends with other rising street thugs across the city as teen. By the time Prohibition hit, Frank Costello had made a name for himself in certain circles of the underworld and joined forces with Charlie Luciano, Vito Genovese, Meyer Lansky, Benjamin Siegel and others running booze locally in an operation funded by Arnold Rothstein.

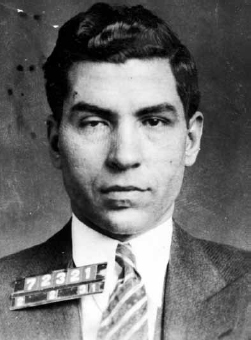

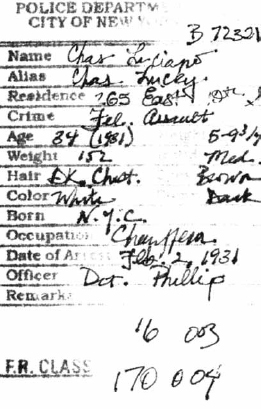

Mug shot of a young Frank Costello.

In 1929, he played an important role in establishing the National Crime Syndicate, and during the Mafia restructuring of 1931, Costello earned the consigliere position in the new Luciano crime family, making him third in command behind Luciano and underboss Vito Genovese. Costello proved to be one of the most business-minded gangsters of the era, and he made the Luciano family a fortune in the slot machine, race wire, loan-sharking and casino rackets.

By 1937, with boss Luciano behind bars and underboss Genovese in Italy evading murder charges, Costello became acting boss of the family. Under his direction, the organization acquired a near monopoly on various gambling enterprises across the United States. He had become so wealthy and powerful that virtually every crooked politician and city administrator of the era was either installed by Costello or in his pocket.

Costello was said to be one of the last of the old-timers who did not promote the sale of narcotics; he felt it was not worth the risk. Too many low-level criminals and associates outside the family had to be involved, and potentially long prison sentences made people talk. In what would be proven by the 1950s, a single street pusher turned informant had the potential to put an entire crew behind bars.

If it weren’t for murder, graft, extortion and otherwise illegal practices, Costello would have been remembered as one of the most prominent and ingenious businessmen of the era, and he wanted to be respected as such. Costello worked hard to maintain a clean image; his social circle included the highest-level politicos, entertainers, industrialists and socialites of the generation.

Well liked and highly respected, the crime lord’s only real threat came from inside his own family. When Vito Genovese returned to America, he believed the boss position was his, only found that it was extremely difficult to gather any support for an overthrow. Costello simply made everyone too much money and had too many powerful allies.

Genovese was the opposite of Costello. He was said to be brutish and violent and had made many enemies in his career. He did allegedly promote narcotics trafficking and had none of the business or social savvy that made Frank Costello so successful. It didn’t appear that Costello had anything to worry about; however, things started to unravel for him in the early 1950s.

Luciano family underboss Guarino “Willie” Moretti—Costello’s blood cousin and most trusted associate—was murdered in a Clifton Park, New Jersey diner on October 4, 1951. It was a major personal and professional setback for Costello.

Then, in 1952, he served his first prison term in over thirty years: eighteen months for refusing to answer questions during the infamous Kefauver hearings on organized crime. There was little his high-powered friends could do—the entire proceedings were televised to the world.

In 1954, he spent another eleven months behind bars before a five-year tax evasion sentence was overturned. While in prison for a third time in 1956, another important ally, Joe Adonis, was deported to Italy. Genovese realized he had an opportunity to stage a coup and began to garner support from his young stable of street soldiers, including Vincent “Chin” Gigante.

One last major obstacle stood in the way: Mangano family boss Albert Anastasia. The former Murder, Inc. hit man was now leading one of the most powerful crime families in the country and was a staunch ally of Costello’s. Unfortunately for Costello, Anastasia fell into bad terms with many top mobsters, including Meyer Lansky, when he began establishing competing gambling rackets.

With the go ahead from the top bosses, Anastasia was involuntarily retired in October 1957. Now, Genovese, after a decade of plotting patiently, was clear to make a move against Costello.

On May 2, 1957, seven months after the murder of Anastasia, Vincent Gigante followed Frank Costello into the lobby of his apartment building. As Costello approached the elevator, Gigante yelled out, “This is for you, Frank!” and fired a shot at the boss’s head from just a few feet away.

The warning was a blessing for Costello, who reacted just in time, and the bullet only grazed his skull. Gigante fled the scene, convinced that he had just killed the most powerful criminal in America; however, Costello recovered. But the incident was enough to force Costello into relinquishing his position as boss. Genovese had killed and manipulated his way to the top of the family that would come to bear his name.

Frank Costello was able to keep much of his illegal interests and spent the rest of his life behind the scenes, acting as an adviser to the family until his death of a heart attack in 1972. He was eighty-two years old.

The criminal legend was buried at Saint Michael’s Cemetery in Queens.

D’AQUILA, SALVATORE

91 Elizabeth Street, 1919

Alias: Toto

Born: 1878, Sicily

Died: October 10, 1928, New York City

Association: D’Aquila crime family boss

Salvatore D’Aquila was a powerful transplanted Mafioso from Palermo who ruled the American Mafia at the dawn of Prohibition.

With a record in the United States dating back to 1906, D’Aquila was a highly intelligent gangster who also seemingly happened to be in the right position at the right time. First, his outfit’s biggest early century rival, the Morello gang, suffered a huge setback when its leaders were sentenced to lengthy prison terms in 1909.

Then, in 1916, Morello gang leader Nicolas Terranova was ambushed and killed by a Neapolitan gang out in Brooklyn. Not only did the Morellos lose another strong leader, but also Pellegrino Morano, the boss of the gang that did the shooting, was arrested and eventually deported back to Naples.

91 Elizabeth Street today. Courtesy of Shirley Dluginski.

Elizabeth Street, looking north from Hester Street, 1902. Library of Congress.

With two major adversaries out of the way in one fell swoop, D’Aquila capitalized by absorbing as much Brooklyn territory as possible and expanding his operations in East Harlem and the Lower East Side—a location that would prove to be valuable in the ensuing bootlegging wars of the 1920s, giving D’Aquila a leg up on competition in this city.

D’Aquila was arguably the most powerful member of the American Mafia by the beginning of Prohibition in 1920. His influence extended to several East Coast and midwestern cities, and he had a virtual monopoly on much of the Italian underworld alcohol trade in of this city; that is, until the remaining Morellos found a formidable new leader by the name of Giuseppe Masseria.

On a crisp fall evening in 1928, the nearly three-decades-long career of Salvatore D’Aquila ended in a hail of bullets on an Avenue A street corner. Masseria replaced D’Aquila as head of the Italian underworld.

DELLACROCE, ANIELLO

232 Mulberry Street, 1914–1960s

Alias: Father O’Neil

Born: March 15, 1914, New York City

Died: December 2, 1985, New York City

Association: Gambino Crime Family Underboss

With a criminal career spanning half a century, this longtime influential mob leader was a protégé of Albert Anastasia in the 1930s and a mentor to John Gotti in the 1970s.

Born and raised in the heart of Little Italy (232 Mulberry Street was his lifelong home address), Dellacroce’s first arrest was at sixteen years of age for the robbery of a local man named Antonio Derosa. Within a few years, he found himself working for Mangano family underboss and Murder, Inc. gunman Albert Anastasia. Dellacroce headquartered out of the Ravenite Social Club, where he allegedly oversaw loan-sharking, extortion and other illegal activities for three decades between the 1950s and 1980s.

232 Mulberry Street, the nearly lifelong home address of Aniello Dellacroce, today. Courtesy of Shirley Dluginski.

Some insiders believe Dellacroce was a triggerman in the murder of an Anastasia (Gambino) family capo referred to as Johnny Roberts, who was loyal to underboss Carlo Gambino’s bid to dethrone Albert Anastasia in the 1950s. Despite his early support of Anastasia, Dellacroce somehow was able to make peace with Gambino by the time he took over the family in 1957 and was allowed to retain his position as capo. When Joseph Biondo died in June 1966, Dellacroce was elevated to underboss.

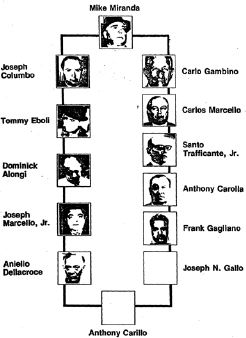

Shortly after becoming underboss, on September 22, 1966, Dellacroce and a dozen fellow Mafia leaders gathered at the La Stella Restaurant in Forest Hills, Queens (at 102–11 Queens Boulevard), in what has become known as the Little Apalachin conference.

With the party secluded in a private basement dining room and the meeting underway, police burst through the door and arrested all thirteen guests as material witnesses to several Queens County murders and organized crime rackets. It was the most successful roundup of mobsters since the 1957 Apalachin incident, in which sixty were arrested fleeing from an upstate farmhouse. Detectives said that the purpose of the raid was to “keep track of how the men relate to each other in importance within the underworld hierarchy.”21

La Stella Restaurant’s “Little Apalachin” seating arrangement, September 22, 1966: Carlos Marcella (New Orleans boss), Joseph Marcello (Carlos’s brother), Santo Trafficante Jr. (Tampa boss), Thomas Eboli (Genovese acting boss), Aniello Dellacroce (Gambino underboss), Mike Miranda (Genovese consigliere), Joseph Colombo (Colombo boss), Joseph Nicholas Gallo Jr. (Gambino capo, future consigliere), Carlo Gambino (Gambino boss), Dominick Alongi (Genovese capo, future acting underboss), Anthony Corolla (New Orleans, future boss), Frank Gagliano (New Orleans, future underboss) and Anthony Carillo (Genovese soldier). Federal Bureau of Investigations, NARA Record Number 124-10371-10179.

A hearing was held for twelve of the thirteen on December 19, 1966 (minus Gambino, who was excused due to poor health). The defense team made headlines when they accused Queens district attorney Nat N. Hentel of conducting a publicity stunt in order to further his career. One lawyer stated, “Barnum and Bailey couldn’t have dreamed up a bigger three-ring circus.”22 Despite not being charged with a crime, the mobsters were held on $100,000 bail; most paid that within thirty-two hours and went free.

On November 25, 1966, local police raided the Ravenite Social Club on Mulberry Street and arrested Dellcroce, Joe N. Gallo, Paul Castellano and eight others who were out on bail. All charges were dismissed within a few hours by a night court judge because the arresting officers could not provide evidence that the group was gathered for the purpose of engaging in illegal activities.

On November 30, seven of the La Stella arrestees were called to testify before a grand jury, but they offered nothing but their names and addresses. In a show of defiance, the mobsters and their lawyers actually went to La Stella for lunch during the hearings, and the press followed. The resulting story and accompanying photos made the newspapers, and it became a public embarrassment for the prosecutors. As District Attorney Hentel became desperate for the case not to collapse, full immunity was offered to all thirteen mobsters in exchange for testimony; again, all balked at the proposition.

On May 18, 1967, Dellacroce, Miranda, Carillo and Gallo were rearrested and charged with contempt of court. All four men pleaded not guilty the next morning and were released on $5,000 bail. Eboli, Alongi and Colombo were also named in the indictment, but Eboli did not turn himself in until January 4, 1969.

Despite the media circus, the case lost steam and eventually fizzled out.

Evading serious prison time throughout his life, seventy-one-year-old Dellacroce was eventually indicted on March 28, 1985, under federal racketeering (RICO) charges, as part of an investigation that sent the top dozen New York Mafia leaders (and dozens more) to prison. However, Dellacroce would die of lung cancer eight months later, before being sentenced.

One reliable insider told me a story of how Dellacroce and Peter DeFeo were longtime rivals, and on one occasion in Las Vegas, the pair got physical and had to be separated. Stories like this are not documented and unfortunately cannot be proven.

D’ERCOLE, JOSEPH

428 East 116th Street, Apartment 18

Alias: Joe Z, Josey, Joe Morelli, Josie Romano, Joe the Book

Born: November 16, 1911, New York City

Died: May 1976

Association: Gambino crime family

According to the FBN, this portly, five-foot-seven, 210-pound mobster—whose official employment was that of a bouncer at the Delightful Luncheonette at East 116th Street and 1st Avenue—was a “controlling member” of the Mafia in Harlem by the 1950s and engaged in large-scale narcotics sales and auto theft.

Twenty-five-year-old D’Ercole was arrested in 1936, along with nine other members of the Manhattan Social Club (354 East 114th Street) in connection with the murder of gangster Dutch Schultz and his three bodyguards in Newark, New Jersey, on October 23, 1935.

Police traced a car found at the murder scene back to club member Joseph Tortotici23 and raided the East Harlem establishment on January 7, 1936. It turns out that Tortotici had lent his car to Schultz bodyguard Bernard Rosenkrantz on the day of the hit, but since there was no direct connection with the murder, Tortotici, D’Ercole and their crew were only charged with vagrancy.24

In the early 1950s, a Bronx-based front for a large-scale auto-theft ring was established by D’Ercole under the name United-Drive-Yourself. Using the name Joseph Romano, D’Ercole and his associates resold over one hundred stolen cars within its first week of operation in October 1953.25

In 1964, D’Ercole was sentenced to twenty years in prison for heroin distribution;26 he died sixteen years later.

DEFEO, PETER

219 Mott Street, 1910–20; 276 Mulberry Street, 1930; 130 West Twelfth Street

Alias: Phil Aquilino

Born: March 4, 1902, New York City

Died: April 6, 1993, New York City

Association: Genovese crime family capo

This “Mayor of Little Italy” was a popular longtime capo in the Genovese crime family who also operated the Ross Paper Stock Company at 150 Mercer Street and Ross Trucking Company on Mulberry Street through the 1980s.

DeFeo’s parents, Giuseppe and “Mary,” immigrated to New York City in 1893 at sixteen and thirteen years old, respectively. They married soon after, in 1896, and gave birth to Peter while living on Mott Street.

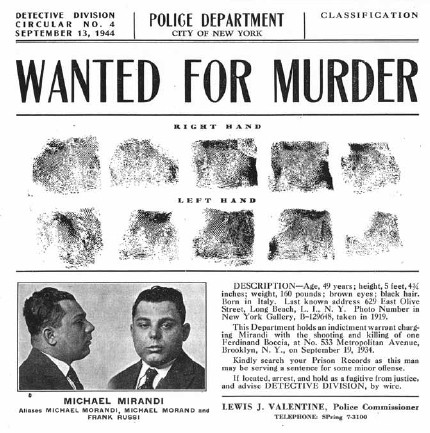

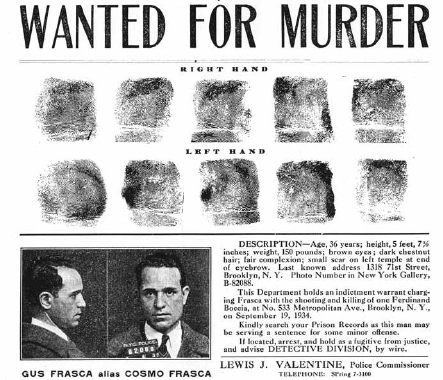

Young Peter DeFeo “came up” through a Vito Genovese crew based in his native neighborhood, which was led by (future consigliere) Michele “Mike” Miranda. DeFeo proved his loyalty to Genovese on September 9, 1934, when he, Miranda and three associates gunned down a man named Ferdinand “the Shadow” Boccia, a racketeer who had a fallout with Genovese over a business venture. Both Genovese and DeFeo were indicted for the murder, but Genovese fled to Italy, while DeFeo hid out at a hotel resort in Tennanah Lake, New York.27

The group would eventually reunite in New York City, where DeFeo continued his support of underboss Vito Genovese’s quest for control of the family. By the time Genovese had dethroned Costello via a bullet to the head in 1957, DeFeo had risen to the rank of capo and would, for the next couple of decades, control his crew’s operations out of Little Italy.

In October 1963, DeFeo and six other Mafioso were arrested while drinking coffee in Lombardi’s Restaurant at 53 Spring Street and charged with “consorting for unlawful purposes”; however, all charges were dropped by November 3.28

In May 1968, Peter DeFeo, along with gangsters James “Jimmy Doyle” Plumeri and Edward “Eddie Buff” Lanzieri, was charged with conspiring to share in tens of thousands of dollars in kickbacks from union member welfare and pension plans.29

In August 1969, DeFeo was identified in a Unites States Justice Department press release listing the nation’s top Mafia bosses.30 Between 1969 and 1970, DeFeo’s name was mentioned several times by witnesses in the public hearing of a Joint Legislative Committee on Crime investigation into the mob.

In 1979, during a two-year investigation into corruption of the local construction industry, authorities taped the president of the twenty-five-thousand-strong New York District Council of Carpenters, Theodore “Teddy” Maritas, bragging about his mob connections, including the admission of “belonging” to DeFeo, stating, “As far as Pete’s concerned, you know this…the carpenters are his. Let’s face it, including myself.”31

Maritas was also co-chairman of Ed Koch’s labor committee during his 1977 mayoral bid. Koch later appointed Maritas to the Public Development Corporation, a city agency that develops building projects, but in 1981, he was brought up on charges of racketeering, extortion and taking payoffs to permit nonunion members to work on construction sites. Before Maritas had a chance to stand trial, he disappeared.

Peter DeFeo retired in the late 1980s and passed away of natural causes at ninety-one.

DIOGUARDI, JOHN

169 Forsyth Street, 1920

Alias: Johnny Dio

Born: April 29, 1914, New York City (b. Dioguardi, Giovanni Ignazio)

Died: January 12, 1979, Lewisberg, Pennsylvania (federal prison)

Association: Luciano/Genovese crime family

Johnny Dio, as Dioguardi is best known, was a prominent and well-respected Mafioso who wielded great power over New York City’s garment industry and was instrumental in Jimmy Hoffa’s bid for presidency of the Teamsters union.

Along with his two brothers, Frankie and Thomas, Dioguardi was raised in a mob family and introduced to the Mafia as a teenager. Their father, Giovanni Dioguardi, was killed in August 1930 in what authorities called a mob-associated hit,32 and his uncle was Giacomo “Jimmy Doyle” Plumeri, a Lucchese crime family member.

By the early 1930s, young Johnny Dio was working for a Plumeri crew as a labor-slugger in the garment industry, a job that introduced him to the politics of the labor unions he would eventually control.

In March 1937, Dioguardi was sentenced to three years in Sing Sing prison after pleading guilty to charges of extortion, conspiracy and racketeering. After his release, he spent a short time in Allentown, Pennsylvania, before returning to New York City.

James Riddle Hoffa (February 14, 1913–?) was a powerful midwestern Teamster leader who had established the Central States Pension Fund in the early 1950s, a fund that subsequently allowed the Mafia access to millions of dollars in union pensions.33 (It is said that much of the mob’s casino activity in the 1950s was funded by the illegal Teamster pension program.) In a bid for the Teamster presidency, Hoffa’s greatest obstacle was the support of New York City unions, so he sought to form alliances with Anthony Corallo and John Dioguardi.

Hoffa was introduced to Dioguardi by Paul “Red” Dorfman, president of the Waste Handler’s Union. Dioguardi was not a Teamster, but several influential United Auto Workers–American Federation of Labor (UAW-AFL) locals were under his control, and he’d had a working relationship with the organization since the 1930s. Corallo outright owned one Teamster local and controlled several others.34

Dioguardi spent sixty days in jail for tax evasion in 1954, which led to his removal from the UAW-AFL, but by December 1955, he and Corallo had chartered seven “paper” Teamster locals—phony organizations with the minimum required membership—which helped Hoffa win the presidency in 1956, a position he would hold until 1971.

That same year, Dioguardi was indicted,35 along with five associates, for conspiring to injure a federal racketeering trial witness named Victor Riesel, who had sulfuric acid thrown in his face by Abraham “Leo” Telvi on April 5, while exiting the old Lindy’s Restaurant at 1655 Broadway. Reisel was a popular labor journalist who was outspoken against the mob’s racketeering operations and had finished a radio interview critical of local union leaders just hours before the attack took place.

Telvi, who was himself injured in the assault when the acid splashed on his face as well, sought to be compensated above what was agreed for the hit. The twenty-year-old hired thug apparently felt that Dioguardi, who had recruited him for the job, would be easy to shakedown since the mobster was under the scrutiny of law enforcement. Dioguardi agreed to pay; however, Telvi was gunned down outside 240 Centre Street before he had a chance to collect. All charges against Dioguardi in the Riesel attack were eventually dropped after several trial delays.

Legal troubles were just beginning for the veteran gangster, who would spend most of the rest of his life in court or behind bars. In August 1957, Dioguardi refused to answer questions from the United States Senate Select Committee on Improper Activities in Labor and Management, which was investigating his relationship with Hoffa and illegal union activity.

Over the next decade, Dioguardi faced a series of back-to-back trials—charged with everything from extortion to tax evasion—but stealthy tactics by his legal team kept the mobster from spending any lengthy time in jail until 1970. On October 2 of that year, fifty-six-year-old Dioguardi entered a Lewisburg, Pennsylvania prison to begin serving a five-year sentence for bankruptcy fraud and conspiracy. He would not see the light of day as a free man again.

While in prison, a forty-count indictment was filed on May 27, 1971, against Johnny Dio and eight associates, charged with conspiring to “violate provisions of the federal securities laws and regulations”36 (stock fraud), as well as federal mail and wire fraud. On January 26, 1973, Dioguardi was found guilty on four of nineteen counts against him and sentenced to an extra thirty years behind bars.

Dioguardi’s following convictions—April 12, 1973 (nine years), and February 5, 1974 (ten years),37 to be served concurrently—ensured a virtual life sentence. Dioguardi spent the last few years of his life at Lewisburg Federal Prison in Pennsylvania, infamous for housing numerous high-profile inmates over the decades, such as John Gotti, Al Capone, Henry Hill, Paul Vario and Jimmy Hoffa.

DI PALERMO, CHARLES

260 Elizabeth Street, 1950s

Alias: Charlie Beck, Charlie Brody

Born: February 15, 1925, New York City

Died: [?]

Association: Bonanno crime family

Along with brothers Joseph and Peter, Charles made up one-third of the notorious Beck Brothers, suspected narcotics distributors and trusted associates of top Mafia leaders.

Charles, the youngest of the clan, possessed a criminal record dating back to 1945 with arrests for forgery, alcohol violations and burglary. His role in an international narcotics ring earned him a twelve-year prison sentence in 1959 (see Di Palermo, Joseph).

DI PALERMO, JOSEPH

246 Elizabeth Street, 1950s

Alias: Joe Beck, Joe Palmer

Born: June 8, 1907, New York City

Died: [?]

Association: Bonanno crime family

Joseph, the eldest Di Palermo sibling and reputed leader of the Beck Brothers, has a long and storied criminal record dating back to 1925 (the year his youngest brother, Charles, was born). Joseph Di Palermo is perhaps most famous for his suspected role in the 1943 murder of news publisher Carlo Tresca.

Despite the candy store front (46 Prince Street) and his slim, five-foot, six-inch, 120-pound frame, Di Palermo was at one time one of the Mafia’s most feared enforcers. The FDN described him as “a most vicious criminal,” with arrests for everything from liquor violations to homicide by the time his legal troubles really started in the 1950s.

In September 1950, Di Palermo was sentenced to seven years in prison for his role as ringleader of a million-dollar traveler’s check counterfeiting operation, but he was back on the streets by 1955, allegedly spearheading an international narcotics distribution operation based out of East Fourth Street on the Lower East Side.

By the spring of 1955, Di Palermo, Ralph Polizzano, Natale Evola and several other ring members were suspected of importing large quantities of pure heroin from Europe and Cuba to the gang’s plant: Ralph Polizzano’s apartment at 36 East Fourth Street. At this location, Polizzano and the youngest Beck Brother, Charles Di Palermo, would allegedly dilute and repackage the drugs for street sale and then hand off suitcases to mules at Al’s Luncheonette (34 East Fourth Street) or the Squeeze Inn bar (57 East Fourth Street).38

One witness named Nelson Silva Cantellops would later testify that between March 1955 and June 1957, he was paid up to $1,000 for each (almost weekly) trip he made to cities like Las Vegas, Miami and Chicago. According to Cantellops, the men also planned on purchasing and taking over “policy banks” in the Eldridge Street area, to use as a front for their narcotics distribution operation. He claimed that in October 1955 the gang met at Ralph Polizzano’s apartment, where it was concluded that the scheme would cost between $100,000 and $150,000 and needed approval from “the right man,” meaning Vito Genovese.

Some sources in the know believe Cantellops was never involved in the ring and provided misleading information to police to save himself from a minor drug possession charge. One insider described the witness as a low-level, part-time street pusher with a string of arrests for petty crimes, like passing bad checks. Following up, Cantellops was indeed pinched in 1952 for attempting to use a suspect check worth $35.42 at a deli at 104 Columbus Avenue.

Regardless, the entire case didn’t ride on Cantellops’s testimony: the operation was shut down when associate Salvatore Marino was arrested on a drug run in July 1957. While in police custody, Marino claims that police beat him until he was “knocked out,” at which time he gave up the address of the plant under duress. Within a few hours of Marino’s arrest, police raided Ralph Polizzano’s apartment, uncovering heroin, cocaine and all the materials needed for large-scale packaging and distribution.

Thirty-seven defendants and fourteen co-conspirators were indicted, but only seventeen ended up standing trial, including Joseph and Charles Di Palermo, for “conspiracy to import and smuggle narcotic drugs into the United States; to receive, conceal, possess, buy and sell the drugs; to dilute, mix and adulterate the drugs prior to their distribution; and to distribute the drugs.”39 On April 17, 1959, Joseph Di Palermo was sentenced to fifteen years in prison.

Di Palermo and Genovese would be housed in the same Atlanta prison as future informer Joe Valachi. According to Valachi, while locked up in 1962, he felt that family boss Vito Genovese was out to have him killed, suspected of working with the federal authorities. On June 22 of that year, Valachi bludgeoned to death a fellow inmate he says he mistook for Genovese’s go-to hit man, Joseph Di Palermo, hoping to make a preemptive strike. Faced with first-degree murder charges and the possibility of being whacked in prison, Valachi negotiated a deal with the FBI that probably saved his life, but it turned the Mafia inside out and led to revelations that continue to fascinate and terrify the public to this day.

DI PALERMO, PETER

61 Second Avenue, Apartment 3-B, 1950s

Alias: Petey Beck, Pete Palmer

Born: October 18, 1914, New York City

Died: [?]

Association: Bonanno crime family

Along with brothers Joseph and Charles, Peter made up one-third of the notorious Beck Brothers. His record dates back to 1931 with arrests for counterfeiting, alcohol manufacturing and receiving stolen goods. According to the Federal Bureau of Narcotics, Di Palermo frequented the Thompson Social Club at 21 Prince Street and Nancey’s Candy Store at 240 Elizabeth Street but had no record of owning a legitimate business.

In 1950, Di Palermo was convicted on three counts of counterfeiting and sentenced to fifteen years in prison. Di Palermo attempted to appeal by arguing that he was suffering from encephalitis (sleeping sickness) during the first trial and that he had been essentially deprived of his constitutional right to proper representation. He was unsuccessful.40

DI PIETRO, CARLI

21 Monroe Street, 1962; 1 Cardinal Hayes Place

Alias: Charles, Cosmo

Born: October 15, 1930, New York City

Died: 197841

Association: Genovese crime family

This Genovese crime family mobster was a former professional boxer and suspected narcotics smuggler with ties to the Canadian Mafia, as well as part owner of the Vivere Lounge at 199 Second Avenue.

Di Pietro was a childhood and lifelong friend of fellow gangster Frank Mari. As teenagers on the Lower East Side, the boys invented various schemes and hustles to earn a buck, wisely seeking the blessing of the local mob first. No matter how trivial, the wise guys in training always paid tribute and showed respect. So the mob, impressed with Di Pietro and Mari, gave them permission to push small amounts of heroin around Rivington and Stanton Streets, which earned the team about $20,000 a year.42

Di Pietro and his old friend, Frank Mari, were inducted into the Mafia in 1957 during a ceremony presided over by Thomas Lucchese, Albert Anastasia and others. Di Pietro went to the Genovese, and Mari was recruited by the Bonannos.

Di Pietro would soon find himself involved in a major narcotics operation that allegedly brought large amounts of heroin to New York City through Canadian criminal networks. The ring, which included Frank Mari and was led by Carmine Galante, set up its plant in an apartment at 226 East Eighteenth Street. After allegedly processing and packaging the drugs at this location, large quantities would be delivered to several locations in Brooklyn and Manhattan, including the Vivere, where it was passed off to street distributors in shoe boxes and suitcases.43

Federal authorities caught up with the crew by the end of the 1950s. Di Pietro, Galante and several codefendants were convicted on July 10, 1962, after a colorful ten-week trial rife with several outbursts and attempts by the co-conspirators to disrupt proceedings in hopes of “provoking an irreversible error.” Despite underhanded tactics and several appeals, Di Pietro and Galante were sentenced to twenty years in prison and fined $20,000 each. (Mari was the only one who avoided being sentenced; he was acquitted.)

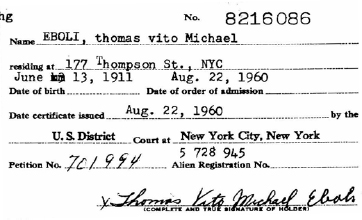

EBOLI, THOMAS VITO MICHAEL

177 Thompson Street, 1960

Alias: Tommy Ryan

Born: June 13, 1911, Scisciano, Italy

Died: July 16, 1972, Brooklyn, New York

Association: Genovese crime family acting boss

This former professional boxing manager worked as a bootlegger in the Masseria crime family as a teenager and had become Vito Genovese’s personal guard by the 1930s. Despite multiple arrests for gambling and disorderly conduct, Eboli’s only recorded conviction came in the 1960s, when he spent sixty days in jail for assaulting a referee at Madison Square Garden after a fighter he managed lost a bout.

Eboli was made capo in 1957 and awarded control of the Genovese family Little Italy crew. When Genovese was sent to prison in 1969, Eboli was made acting boss, though a committee actually made decisions regarding the organization’s operations.

At one point in the early 1970s, it is said that Eboli borrowed over $3 million from Carlo Gambino to set up a narcotics ring; however, the shortlived operation was thwarted by authorities, and Eboli could not pay his debt. Some theories suggest that Eboli was set up by Gambino in the first place, knowing the money could never be repaid. But $3 million is a lot of money to spend to dispose of a rival.

Thomas Eboli, 1960 naturalization record.

On July 16, 1972, Eboli was shot five times and killed in front of his girlfriend’s Brooklyn apartment by unknown assailants driving a yellow van. This murder remains unsolved.

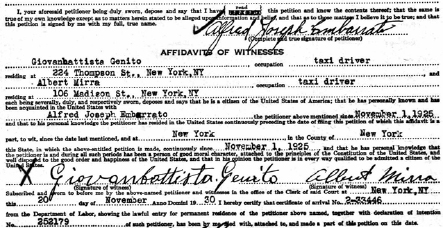

EMBARRATO, ALFRED JOSEPH

96 Oliver Street, 1920; 122 Madison Street, 1925; 43 Market Street, 1950s

Alias: Scalisi, Al Walker, Aldo Elvarado

Born: November 12, 1909, Adrano, Sicily44 (b. Imbarrato, Alfio)

Died: February 21, 2001, Fairfax, Virginia

Association: Bonanno crime family capo

Embarrato was a tough enforcer for the Bonannos who, early in his career, kept a close eye on the mob’s shipping industry dealings along the Lower Manhattan waterfront before getting involved in narcotics distribution and large-scale racketeering.

Sicilian-born Embarrato immigrated to New York City in 1914 at age five, arriving on the steamship Taormina on November 19 of that year with his young siblings, Santina and Giuseppe; a two-year-old boy named Luigi Bivona; and a thirty-three-year-old woman named Carmella Cappella. He grew up on the Lower East Side in the traditionally mob-heavy district around Knickerbocker Village.

96 Oliver, the childhood home of Alfred Embarrato, today. Courtesy of Sachiko Akama.

He was neighbors with the (soon-to-be) father of Anthony Mirra, Albert, who ended up marrying Embarrato’s sister, Carmella (Millie), and was listed as a witness in Embarrato’s 1930 bid at becoming a United States citizen.

Little is known about Embarrato’s initiation into organized crime, but his earliest recorded arrest came in 1930 and his first conviction for violation of federal narcotics laws came on September 9, 1935, with a second in 1955, where he received the minimum five-year sentence as a two-time offender.45 In 1987, Embarrato was indicted on multiple RICO charges, along with several other family members like Joseph Bonanno, Philip Rastelli and Benjamin Ruggiero.46

His troubles continued in 1992, when it was uncovered that the Bonannos and top managers at the New York Post newspaper were working together to illegally inflate circulation numbers. Embarrato held the position of delivery foreman at the Post for several years (though he didn’t actually punch any time cards) and was believed to be organizing the racket. A November 18, 1991 telephone conversation between Embarrato and a Post manager was recorded during a yearlong investigation led by legendary Manhattan district attorney Robert M. Morgenthau. The conversation implicated Post vice-president Richard Nasti and Controller Steven Bumbaca in the scheme, both of whom ended up pleading guilty to labor law violations.47

Alfred Embarrato’s 1930 petition for U.S. citizenship, witnessed by Anthony Mirra’s father, Albert. U.S. petition for citizenship, Southern District of New York, no. 252179.

However, the relationship between the Bonannos and the New York Post may not have ended there. In July 2004, Embarrato’s own nephew, Richard “Shellack Head” Cantarella, flipped and testified that in 2000 the Bonannos conspired with a Post executive to help a garbage-carting company win a contract with the newspaper. The former capo claimed that the carting company paid the Bonannos over $2,500 a month for their help.48

EVOLA, NATALE

12 Prince Street, 1930

Alias: Joe Diamond

Born: February 22, 1907, Sicily

Died: August 28, 1973, Brooklyn, New York

Association: Bonanno crime family boss

Evola was a veteran mobster with a lengthy record dating back to 1930, charged with everything from coercion and gun possession to narcotics trafficking. The future mob leader was allegedly present for a dinner at the Nuovo Villa Tammara restaurant in Coney Island, Brooklyn—the site of Giuseppe Masseria’s murder—during a weekend-long celebration honoring new boss Salvatore Maranzano in August 1931.

12 Prince Street today. Courtesy of Sachiko Akama.

Contrary to the common assertion that he was born in Brooklyn, young Evola arrived in New York City on the SS Indiana on June 3, 1913, with his twenty-seven-year-old mother, Francescio (maiden name Mione), and siblings Giuseppa, Giorlama and Anna and settled in Little Italy.

Evola’s first arrest came while working for Salvatore Maranzano on August 31, 1930, at age twenty-three, for firearms possession. The charges were dropped a year later. His next arrest came on April 3, 1932, for coercion; again, he was acquitted. By this time, Joe Bonanno was boss of the family.

By the early 1950s, using the Belmont Garment Delivery and Amity Garment Delivery Companies (both located at 240–42 West Thirty-seventh Street) as a front, Evola became a major labor racketeer in the city’s garment industry, specifically in trucking and shipping. By this time, he was working under Joe Stracci and James “Jimmy Doyle” Plumeri, before becoming a capo about 1957. Between June 1956 and March 1957, Evola had been subpoenaed to appear before several grand juries in the Southern District of New York and was one of sixty upper-echelon Mafioso who attended the Apalachin Conference in 1957.49 (When interviewed by authorities at his West Thirty-seventh Street office, Evola said he was in Apalachin delivering a few coats for a niece who lived close by.)

In April 1959, Evola was found guilty for his alleged role in a Genovese-Gigante-Di Palermo-Polizzano narcotics ring based out of East Fourth Street, which he appealed. Drug courier turned informant Nelson Cantellops testified that he met Evola several times at various locations throughout the 1955–57 operation and claimed he was instrumental in developing a street distribution route in the Hispanic section of the East Bronx.50

During the appeal trial in January 1960, Evola was sentenced to five years for perjury and conspiring to obstruct justice. On April 5 of that year, his appeal was overturned, and Evola was sentenced to ten years, which he served at Leavenworth Prison in Kansas.

Back on the street by the end of the 1960s, Evola became underboss about 1968 and then, about 1970, replaced an ailing Paul Sciacca as head of the Bonanno family, a position he held until losing a battle with cancer in 1973.

FARULLA, ROSARIO ARIO

315 East Forty-eighth Street, 1942

Born: August 25, 1882, Villarosa, Sicily

Died: February 1971, Italy

Association: Lucchese crime family

Labeled a “vicious and cold-blooded killer” by the FBN, Farulla had close ties to top-level American, Italian and French criminal organizations. His criminal career began in Sicily before spending most of his life in New York City; though according to a 1968 memo, the FBI believed that he eventually became involved in a former Lucchese-run family based out of Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania.

By thirty years of age, Farulla had been sentenced to back-to-back prison terms in his native Sicily: four and a half years on murder and weapons charges in 1908 and two to four months in 1912 for assault and battery. Italian courts would later sentence him to life in prison for murder and theft, but he had already fled the country and settled in New York City, where his first U.S. arrest came in 1929 for bootlegging, possibly working for the Gaetano Reina gang in East Harlem.

In 1953, Farulla was convicted of conspiracy for his role in an international crime ring that allegedly smuggled large quantities of heroin into the United States from France.51 The operation was shut down in October 1953 after being infiltrated by undercover U.S. narcotics agents. Farulla was on the run for almost a month but turned himself in on November 4, 1953, to face charges. The sting led to several arrests on both sides of the Atlantic, including that of Nicolo DiGiovanni, a Sicilian living in Marseille who was the alleged leader of the ring.52

According to Farulla’s Social Security death index, the U.S. Consulate in Italy is listed as his last place of residence before he passed away at age eighty-two.

GALANTE, CARMINE

27 Stanton Street, 1910; 329 East 101st Street, 1930; 235 Sullivan Street; 206 Thompson Street; 134 Bleecker Street

Alias: Lilo, Charles Bruno, Joe Dello, Gagliano, Galanti, Galanto

Born: February 21, 1910, New York City (b. Gigante, Camillo)

Died: July 12, 1979, Glen Cove, New York

Association: Bonanno crime family acting boss

With a criminal record dating back to 1926, Galante earned his criminal stripes as a youth in a street gang on the Lower East Side. By the end of 1930, twenty-year-old Galante had already been arrested in connection with the murder of Brooklyn police officer Walter De Castilla and was wounded in a gun battle that also injured two young children. At the time, he was listed as working as a sorter at the Fulton Fish Market, but by February 1941, he was sponsored into the International Longshoreman’s Association (ILA) union by his brother, Sam Galante, and earned a “position” at the New York and Cuba Mail Steamship Company as a stevedore. By the end of the following year, Galante had also been “employed” at the General Electric Plating Company at 176–80 Grand Street (as a handyman), the Knickerbocker Trucking Company at 520 Broadway (as a helper) and at an unnamed pastry shop at 13 Prince Street.

By the 1940s, Galante was known to the FBI as a Mafia member and was said to have worked as a hit man for Vito Genovese. In 1942, he became the prime suspect in the assassination of news publisher Carlo Tresca, but like the many other murders Galante is alleged to have participated in, no conviction was handed down.

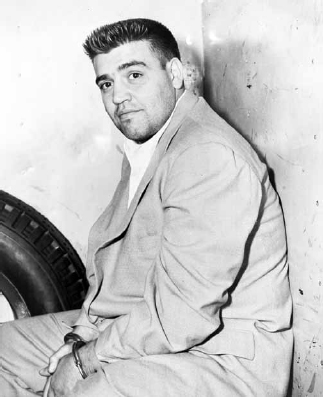

Carmine Galante mug shot, 1943.

In 1945, Galante moved to Brooklyn with his new wife, Helen Marulli of 96 Henry Street. The marriage ceremony was held at Our Lady of Sorrows, at 213 Stanton Street. His best man was fellow mobster Angelo “Moey” Presenzano, a figure who may have played a role in Galante’s assassination three decades later.

Galante was one of sixty upper-echelon mobsters to attend the Apalachin Conference on November 14, 1957, held on the upstate New York property of close associate Joseph Barbara. Over the next two decades, Galante’s loyalty propelled him up the Bonanno family ladder, from consigliere to underboss to acting boss in the 1970s.

While acting boss, Galante was said to have made a lot of enemies by incorporating Sicilian Mafia members into his inner circle, leaving the other New York families out of lucrative operations. He waged a war on the Genovese and Gambino families, leading to the murders of at least eight rival family members. It is even said that he had the mausoleum of deceased rival Frank Costello blown up. By the end of the decade, the commission allegedly decided that Galante was dangerous and had to be eliminated.

At 2:45 p.m. on July 12, 1979, Carmine Galante was eating lunch at a restaurant in Brooklyn (205 Knickerbocker Avenue) when three men burst through the front door, opened fire and killed Galante and his table guests before fleeing in a blue 1974 Mercury.

Galante had undergone several psychiatric examinations over his lifetime while incarcerated, including a 1931 evaluation at Sing Sing and one in 1938 at Clinton State Prison, both of which declared him “psychopathic.”

GAROFALO, FRANK

339 East Fifty-eighth Street (Midtown East, 1930s and 1940s)

Alias: Frank Carroll, Garafola, Garofola

Born: September 10, 1891, Castellammare Del Golfo, Sicily (b. Garofalo, Francesco)

Died: [?]

Association: Bonanno crime family

Described by the FBN as a “top ranking…enforcer and executioner” for the American Mafia with strong ties to Sicily, Garofalo was a highly respected and influential Mafioso, yet little has been told of his lengthy criminal career in contemporary accounts. When mentioned, he is often reduced to a footnote as a suspect in the assassination of news publisher Carlo Tresca in 1943.

Born in Trapani to Vincenzo and Caterina Garofalo, young Francesco was initiated into the Castellammare cosca as a teenager, a faction that was headed by a man named Magaddino Buccellato.

He arrived in New York City at age twenty-nine on May 26, 1921, aboard the SS Providence. Here, he went to work for the Castellammarese-based Nicola Schiro crime family, for whom he ran a bootlegging crew and formed lifelong friendships with the likes of young Carmine Galante and Joseph Bonanno.

After the 1943 murder of Carlo Tresca, one theory arose that suggested Garofalo arranged the assassination because Tresca personally insulted him at a social event,53 though this is an unlikely scenario. Garofalo was never charged. At the time of the murder, Garofalo lived at and operated the Colorado Cheese Company at 176 Avenue A, as well as the High Grade Packing Company in Merced, California.

Garofalo was said to be semiretired from the mob when, in 1955, he returned to Sicily, where he attended the Grand Hotel des Palmes Summit in Palermo on October 14–17, 1957.54 He then returned to the United States briefly to allegedly take part in the Apalachin Summit in November 1957, when it is suspected that Garofalo briefed the gathered Mafia bosses on the results of the Palermo conference. Though the outcome of both meetings is still largely a mystery, one theory suggests that at least one result was the establishment of a new heroin trade operation between the American and Sicilian Mafias.

In August 1965, seventy-four-year-old Frank Garofalo was swept up in a large-scale crackdown on Cosa Nostra operations in Sicily.55 Shortly after dawn on August 2, Sicilian police executed seven simultaneous raids across the island, resulting in the arrests of several high-ranking Mafioso. The Palermo police, heading the operation, said they possessed evidence firmly linking the U.S. and Sicilian underworlds in a worldwide narcotics distribution ring, alleging that pure heroin was being imported from Asia, refined in Sicily and distributed throughout North America.

Besides Garofalo, seven American Mafia members were indicted, including Joe Bonanno, Carmine Galante and Santo Sorge. Sicilian Mafia boss Giuseppe Genco Russo was also charged. In all, seventeen top-level Mafia leaders were put on trial for criminal conspiracy, as well as narcotics and currency trafficking. In an unprecedented move, investigating judge Aldo Vigneri visited America in 1965 to interview several witnesses, including two FBI agents and disgraced mobster Joe Valachi, who was housed in a Washington, D.C. jail cell at the time.

Despite presenting eight years of evidence and several witnesses, prosecutors failed to prove their case, and all charges were dropped against all defendants in June 1968. Frank Garofalo disappeared from public record after that.

GENOVESE, VITO

29 Washington Square West, 1944

Born: November 27, 1897, Naples, Italy (b. Genovese, Avito)

Died: February 14, 1969, Springfield, Missouri

Association: Genovese crime family boss

Not many other Mafioso of the era quite match up to the fearsome reputation of Vito Genovese, the churlish mob leader who had no problem using violence on anyone who stood in his way. Fellow mobsters, friends and civilians were all fair game to the man who went on to lead arguably the most infamous (and powerful) Mafia organization in America.

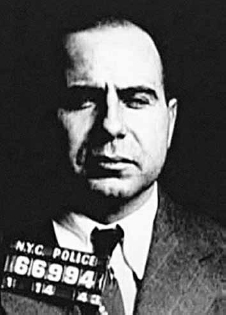

Vito Genovese mug shot.

According to Mafia insiders, Genovese entrusted very few to his inner circle and was one of the most inaccessible bosses of La Cosa Nostra. The stealthy mobster enforced an elaborate chain of command between himself and his underlings and was known to pass his own (Mafia) family members on the street without so much as a glance. Was this a crafty ploy to evade the authorities or an example of the gangster’s icy personality? Those in the know think it was a little of both.

Born to Felice and Nunziata Genovese in Rosiglino, Tufino, a province of Naples, Italy, the future mob heavyweight immigrated to New York City with his family about 1914. His first arrest came soon after—a weapons possession charge in Manhattan on January 15, 1917, that earned the twenty-year-old aspiring gangster sixty days in the workhouse, a term he served between June and July of that year.

A string of six arrests between 1918 and 1925 on charges ranging from felonious assault to homicide (twice), all ended in a discharge. Genovese would only see the inside of a jail cell once more until the 1950s—thirty days in January 1927, with which he also received a $250 fine.

By this time, the five-foot, seven-inch, 160-pound Genovese had established himself as a feared Prohibition-era strong-arm for hire and was planting the seeds of his own alcohol and gambling rackets in both New York and New Jersey with partners such as Charlie Luciano. By the end of the 1920s, Genovese had been recruited by the Giuseppe Masseria crime organization and made Luciano’s underboss in the 1931 restructuring of the Mafia.

On June 20, 1930, four men were arrested in a Secret Service–led raid on an alleged Bath Beach, Brooklyn counterfeiting plant (1726 Eighty-sixth Street), where almost $1 million in suspicious currency was “ready to be placed into circulation.”56 Eight men were indicted on June 30, including suspected ring leader of the operation Vito Genovese, though he was not in police custody at the time of the indictments.

The ring was accused of manufacturing $200,000 in fake $20 notes over a three-month period between April and June 1930 and received a fair amount of press. The curious thing is that Genovese’s name only appears in the first flurry of reports about the incident—but he is never mentioned again. There is no infraction listed on his police report from this time period, so it seems the gangster escaped charges.

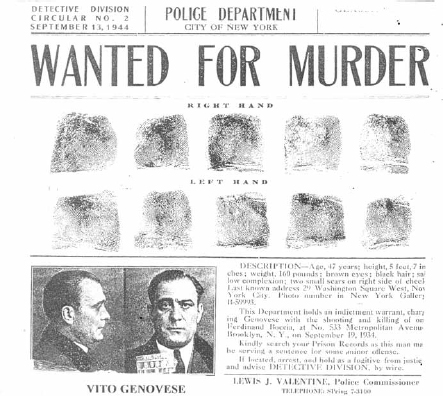

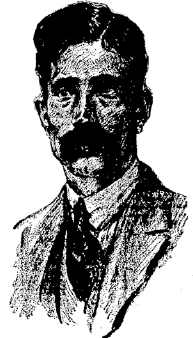

Vito Genovese wanted for the murder of Ferdinand Boccia in 1934. NYPD, New York City Municipal Archives.

His first wife, whom he married in 1924, died in 1931. On March 30, 1932, Genovese married Anna Petillo, who was not exactly available—that is, until her husband, Gerard Vernotico, was found strangled to death on the roof of 124 Thompson Street on March 16, only two weeks before her wedding to the mobster. All gangland signs point to Genovese, though the murder remains officially unsolved.

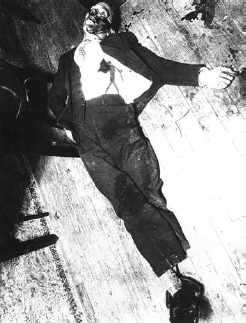

On September 19, 1934, Mafia associate Ferdinand “the Shadow” Boccia was shot to death at the Cristofolo Café, at 533 Metropolitan Avenue in Brooklyn. While he was sitting at a table gambling, two men walked in the front door with guns drawn. Boccia’s uncle, Benny, who managed the place, assumed it was a stickup and offered no resistance. When Benny told the gunmen to take whatever they wanted, one of them stated, “No holdup here gentlemen, we want this rat,”57 and pointed the barrel of his gun at Ferdinand Boccia. It is said that the Shadow was given enough time to say a brief prayer with Rosary beads pulled from his pocket before being shot six times.

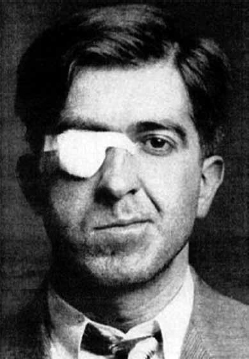

A low-level mob associate turned informant named Ernesto “the Hawk” Rupolo—who earned his nickname after being shot in the eye—eventually confessed to killing Boccia. His testimony led to a murder indictment for six men,58 including Vito Genovese, whom Rupolo claimed contracted him for the job.

Ernesto “the Hawk” Rubulo mug shot, 1945.

Boccia was murdered while clutching Rosary beads. NYPD, New York City Municipal Archives.

Genovese, who had become acting boss of the Luciano family in 1936, when Charlie Lucky was sent to prison, fled to Italy in 1937 to escape prosecution for the murder of Boccia. In his absence, Frank Costello filled the acting boss position and would go on to rule the organization for the following two decades.

In 1946, U.S. authorities extradited Genovese back to New York City, where he stood trial for the 1934 crime. While appearing in Kings County (Brooklyn) Court on June 7, 1946, Ernest Rupolo, who served eight years for the murder, took the stand against Genovese. He testified to meeting the mob boss through future family consigliere Michele Miranda, whom Rupolo claimed had hired him for contract killings in the past. He stated that he first met Genovese at a Brooklyn restaurant, where Miranda introduced him as don vin done, or “the big man.”

When Rupolo leaned over the witness stand, pointed at Genovese and identified him as the person who hired him to assassinate Boccia, Don Vito shifted in his seat and stared at the apostate killer. Rupolo was reportedly visibly shaken. He loosened his tie, unbuttoned his collar and began to sweat.59

Mike Miranda wanted for the murder of Ferdinand Boccia in 1934. NYPD, New York City Municipal Archives.

A second witness named Peter LaTempa was poisoned on January 15, 1945, leaving the prosecutors’ entire case riding on the testimony of an admitted killer and jailhouse rat; needless to say, charges against Genovese were dismissed. Nineteen years later, on August 24, 1964, Rupolo’s body was found washed up on a Queens beach. He was shot, stabbed, bound by rope and chained to a heavy object before being dumped in the East River.

It turns out that Boccia had helped Genovese establish a numbers racket early in 1934 but felt the big man was cutting him out of a fair share of profits. The rest is gangland history.

It is said that Genovese was bitter upon returning to America and playing second fiddle in Costello’s well-tuned Mafia family. For the next decade or so, he would run his Little Italy crew and breed a new generation of loyalist mobsters who helped him plot and murder his way to the top by the end of the 1950s.

It may have seemed like being family boss just wasn’t in the cards for Genovese. His first opportunity in 1936–37 only lasted about a year before he was forced into exile for a decade. After finally wresting control of the organization from Frank Costello in May 1957, Genovese only spent two years on the street before he was sentenced to fifteen years in prison on April 17, 1959, for drug trafficking.

It is kind of remarkable that the family acquired so much power under the circumstances. In those two years after Costello retired, Genovese reversed much of the family’s solid relationships that Costello had developed by making a lot of enemies, as well a few major blunders—like the November 14, 1957 Apalachin Conference he called in upstate New York, where police were tipped off, resulting in the arrests of sixty mobsters. To this day, many people believe that Genovese was set up on drug charges in 1959 in order to remove him from the picture altogether.

Genovese continued to rule and grow his family from behind bars through various front bosses but would succumb to a heart attack on Valentine’s Day 1969. His body was shipped from a federal penitentiary medical center to a funeral home in Red Bank, New Jersey, where services were held.

Vito Genovese was buried at Saint John’s Cemetery in Queens.

GERNIE, JOSEPH

336 East 120th Street, 1950s

Alias: Joseph Yanni, John Gernie

Born: August 4, 1921, New York City

Died: February 1972

Association: Genovese crime family

This Genovese soldier who provided muscle for Anthony Strollo’s crew had an arrest record spanning several decades, including burglary, larceny, gambling, assault and “causing an explosion with intent to kill.”

On September 18, 1957, Gernie was arrested for his part in a narcotics ring that sold heroin to undercover authorities over a three-month period. Gernie was allegedly present at several of these transactions, which were made at various West Side parking garages and cafés throughout the summer of 1956. When arrested, in Gernie’s possession was a marked $100 bill used by agents to purchase heroin just weeks earlier. Gernie was sentenced to ten years in prison on February 19, 1957, and fined $5,000.60

GIGANTE, VINCENT

181 Thompson Street, 1928; 238 Thompson Street, 1950; 134 Bleecker Street, 1957; 225 Sullivan Street

Alias: Chin

Born: March 29, 1928, New York City (b. Gigante, Vincenzo Louis)

Died: December 19, 2005, Springfield, Illinois

Association: Genovese crime family boss

This colorful, hulking, former light-heavyweight boxer and Little Italy native earned his stripes as a Vito Genovese strong-arm before eventually taking over the family in the early 1980s. By the 1990s, Gigante was said to be a powerful leader inside the Mafia Commission, wielding influence over La Cosa Nostra organizations throughout the Northeast.

Vincent was born at 181 Thompson Street Salvatore to Esposito Vulgo and Iolanda Scotto di Vettimo, Neapolitan immigrants who were married in Italy in October 1920, shortly before arriving in New York City. Sometime after settling in America, the family adopted the name Gigante.

The alias Chin (insiders say it was just Chin, not the Chin) was said to have derived from a childhood nickname given to him by his mother, but it also suited him well in the boxing ring. During the 1940s, young Gigante fought in the 170-pound weight class and earned an impressive record of twenty-five wins and four losses (twenty-one wins by knockout).

Chin’s lifelong loyalty to Vito Genovese was said to have originated from an incident in Vincent’s childhood. Genovese allegedly assisted the Gigante family financially when he heard mother Iolanda needed an operation, and young Vincent was forever grateful. By the time Gigante fought his last professional contest in 1949, he had racked up multiple arrests and formed close relationships with several organized crime figures. His boxing manager was none other than Thomas “Tommy Ryan” Eboli, a Genovese strong-arm and future acting family boss.

181 Thompson Street today. Courtesy of Shirley Dluginski.

Vincent “Chin” Gigante mug shot, 1960.

In 1947, Gigante was arrested and charged with arson and grand larceny, though these charges were reduced to malicious mischief, and he was placed on four years’ probation. In June 1950, while on probation, Gigante was sentenced to sixty days in the workhouse for his role in an illegal gaming scheme, which operated betting pools at several Brooklyn colleges. Twenty-one-year-old Gigante was charged with distributing betting cards at various local campuses, where students gambled on basketball games.

During the 1950s, Gigante provided muscle for Genovese’s Little Italy crew and “made his bones” on May 2, 1957, by brazenly attempting to murder family boss Frank Costello in a bid by his mentor to take over the organization. Costello survived the hit, and Gigante went underground, as word that he was the triggerman had reached authorities. While detectives were staking out Chin’s apartment at 134 Bleecker, they stopped two of Gigante’s brothers, Mario and Ralph, who had driven by the location. Mario struck one officer who was questioning him and had to be wrestled to the ground. In the car, they found a hatchet and a baseball bat. Mario Gigante was charged with felonious assault, carrying a concealed weapon, driving without a license and vagrancy, but the brothers did not give up the location of Vincent.