III

GANGLAND HITS

ALFANO, PIETRO

East Side of Sixth Avenue between Eighth and Ninth Streets

On February 11, 1987, two men stepped out of a red Chevy near the corner of Sixth Avenue and West Ninth Street, where fifty-seven-year-old pizza shop owner Pietro Alfano was exiting the old Balducci’s market (424 Sixth Avenue) with his wife and bags of groceries in tow. The pair followed Alfano south for a few yards before one of them pulled out a .38-caliber revolver and fired three shots into his back. When Alfano dropped to the ground, the gunman opened fire on an innocent bystander before fleeing north on foot, back toward West Ninth Street. One assassin jumped in a yellow cab and the other in a blue van, disappearing into the busy downtown traffic.

When thirty-three-year-old Philip Ragosta and forty-one-year-old Frank Bavosa were arrested the the next day, they admitted to receiving $10,000 each for the hit, plus at least $10,000 in expenses, according to the FBI. It turned out that the pair had been following Alfano for months, waiting for the right opportunity to murder him.

A mob connection was quickly established by authorities. Alfano was no ordinary businessman. He was the nephew of Gaetano Badalamenti, a notorious Sicilian Mafia leader at the center of what was called the Pizza Connection case. The shooting victim was a defendant on trial in the infamous case, suspected of being the American point man for a $1.6 billion international heroin-trafficking ring that used pizza shops across the United States as distribution points.

This was the second such shooting related to the case. On December 3 of that year, the body of Gaetano Mazzara, another defendant in the trial, was found in a garbage bag in Brooklyn. However, both Alfano and bystander Ronald Price miraculously survived the nearly point-blank-range hit attempt; organized crime strike force prosecutor Robert Stewart chalked this up to “bad shooting.”131

The attempt on his life may have been a bizarre blessing in disguise for Alfano, who faced life in prison without parole in the Pizza Connection trial. His case was declared a mistrial in July 1987 because he missed the last eighteen days of the seventeen-month trial due to his injuries. None of his eighteen U.S. codefendants fared so well, and all were sentenced to lengthy terms in March 1987.

Those connected to the Sicilian side of the case were not so lucky. Attorney for the U.S. Senate Permanent Investigations Subcommittee Harriet McFaul claimed that “twenty-two police chiefs, judges, politicians and Mafia hunters were murdered before the trial on the so-called Italian end of the Pizza Connection case.”132

ANASTASIA, ALBERT

870 Seventh Avenue, Park Sheraton Hotel

At about 10:20 a.m. on the morning of October 25, 1957, Anastasia was relaxing in a barber chair at this address (now the Park Central Hotel) when two men slipped in the front door, quietly pushed the barber aside and fired several shots at the veteran mobster. Their target, disoriented, stood up and returned fire at his own reflection in the mirror before collapsing on the floor and dying of his wounds. One of the gunmen dropped his .38-caliber Colt revolver, with five spent shots, in the hotel lobby while fleeing. Another revolver was found four hours later in the subway station beneath the hotel; this weapon had only been fired once. Despite the efforts of over one hundred law enforcement officials originally assigned to the case, this assassination remains officially unsolved. However, gangland chatter pointed to “Crazy” Joey Gallo and his brother.

Anastasia had fallen out of favor with the mob and was marked for death by the early 1950s, but the powers that be offered the powerful gangster a chance to live if he retired and relocated from the city. Spending most of the 1950s underground in his Fort Lee, New Jersey home, Anastasia began pushing his luck by frequenting New York City more and more in the months before his death.

Coincidentally, this is the same address where gambler and racketeer Arnold Rothstein was shot on November 4, 1928, in room 349, dying hours later. That murder is also unsolved.

BARETTO, GREGARIO

636 East Thirteenth Street

On July 6, 1971, twenty-nine-year-old Gregario Baretto was shot in the chest by an unknown gunman on the sidewalk at this location near Avenue D. Authorities believed the shooting was part of a brewing war for control of the Colombo family, though Baretto, in critical condition, refused to identify his attacker or cooperate with a police investigation.

BILOTTI, THOMAS

210 East Forty-sixth Street, Sparks Steak House

As bodyguard to Paul Castellano, Thomas Bilotti (March 23, 1940–December 16, 1985) became an unfortunate casualty in John Gotti’s drive to become boss of the Gambino crime family. (See Castellano, Paul, below.)

BONANNO, JOSEPH

Park Avenue at East Thirty-fifth Street

At close to midnight on October 20, 1964, mob boss Joe Bonanno (January 18, 1905–May 11, 2002) was getting out of a car in front of his lawyer’s apartment building at this location when two men forced him into the backseat of a waiting vehicle. Bonanno was held captive in an upstate farmhouse for six weeks before being driven to Texas and released unharmed. The veteran mobster then spent over a year hiding out in the Southwest, disguised in a beard.

At least, that is the story according to Joe Bonanno. Most law enforcement officials and Mafia insiders seriously doubt the kidnapping ever took place. Conveniently for Bonanno, due to the “abduction,” he missed having to testify before a grand jury on October 21 or face incarceration for contempt of court.

Prison time was the least of Bonanno’s troubles. He made a lot of enemies when an alleged plot to murder fellow family bosses Carlo Gambino and Gaetano Lucchese was uncovered. Many theorize that Bonanno fled the city in order to figure out a way to make peace with the Mafia Commission, which was furious over Bonanno’s unsanctioned plan.

Joe Bonanno inherited the family in 1931 and ran it for three decades in relative peace until the early 1960s. His troubles are said to have begun when a popular longtime capo named Gaspar DiGregorio was passed over for a consigliere position in favor of Bonanno’s own son, Salvatore “Bill” Bonanno, causing a rift in the family.

When Joe Bonanno disappeared in 1964, the commission stepped in and appointed DiGregorio acting boss by 1965, infuriating supposed successor Bill Bonanno and his supporters. The resulting “Bonanno War” turned violent as loyalists to both men chose sides and fought for control of the family.

Most of the hostilities ended by 1968, when Joe Bonanno suffered a heart attack and officially retired his throne. Battling factions had united by the end of the decade under the leadership of Natale Evola, who also helped mend the family’s relationship with the Gambinos and Luccheses.

BRIGUGLIO, SALVATORE

163 Mulberry Street

At about 11:15 p.m. on June 26, 1978, two unidentified men approached forty-eight-year-old Genovese crime family soldier “Sally Bugs” Briguglio on the sidewalk outside the Benito’s II restaurant at this address and knocked him to the ground before firing five bullets into his head and one into his chest.

Briguglio was a business agent for the International Brotherhood of Teamsters, Local 560, based out of Union City, New Jersey. At the time of his murder, prosecutors were building a case against Briguglio and Genovese capo Anthony “Tony Pro” Provenzano, implicating the mobsters in the 1961 slaying of rival teamster Anthony Castellito (whose body was never found and was said to have been put through a wood chipper).

The relationship between labor unions and the mob date back to the early twentieth century and perhaps peaked by the late 1950s, when the McClellan Committee began its investigations into organized crime. By 1960, newly appointed attorney general Robert Kennedy had targeted the International Brotherhood of Teamsters, Chauffeurs, Warehousemen and Helpers of America and its president, James Riddle Hoffa. When the organization’s books were opened, investigators found several known Mafia members on the payroll, including Briguglio.

CASTELLANO, PAUL

210 East Forty-sixth Street

At about 5:30 p.m. on December 16, 1985, seventy-year-old Gambino boss Paul Castellano pulled up to the Sparks Steak House in a black Lincoln limo driven by bodyguard Thomas Bilotti. When the pair began to exit the vehicle, three men walked up to them and opened fire with semiautomatic pistols. Each target took six shots to the head and body and collapsed on the street in pools of blood. Two gunmen sprinted down Forty-sixth Street, while one stayed behind briefly to ensure that the job was done, firing a single shot at point blank range into Castellano’s skull before fleeing.

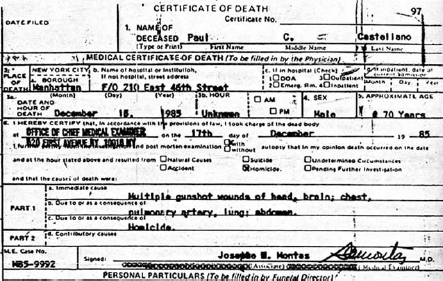

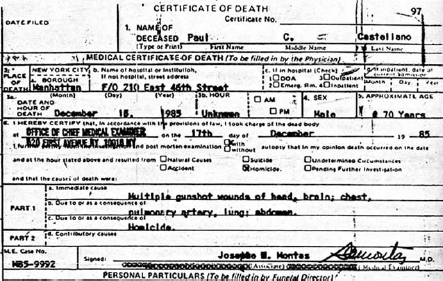

A portion of Paul Castellano’s death certificate.

According to infamous Mafia turncoat Salvatore “the Bull” Gravano, he and John Gotti sat in a car nearby and observed the whole incident, which took no longer than thirty seconds to execute. Gravano recounted, “I believe Paul was shot first. Tommy squatted down to look through the window, kind of squatted down. And then somebody came up behind him and shot him. He [Bilotti] was actually watching Paul get shot.”133

Gotti became boss of the Gambino family after the murder of Castellano, a position he would hold, even from behind bars, until his death in prison on June 10, 2002, at age sixty-one.

COLL, VINCENT

314 West Twenty-third Street

At about 12:45 a.m. on February 8, 1932, Vincent “Mad Dog” Coll and a bodyguard entered the London Chemists pharmacy at this address and headed to a phone booth in the rear of the store. Moments later, a man casually walked in through the front door and approached the booth Coll was standing in. Coll’s bodyguard quietly took off at the sight of a Thompson submachine gun slung under the would-be killer’s right arm, leaving his twenty-four-year-old boss to fend for himself.

According to witnesses, the gunman caught Coll off guard when he approached the phone booth and said, “Turn around Vincent, and get ready for it. I’m going to give it to you.”134 Coll had no chance. He was slaughtered by a hail of bullets from the powerful automatic weapon at close range. One slug tore away his entire nose, and several passed through his body completely.

The sensational murder took place across the street from the Cornish Arms Apartment building at 311–23 West Twenty-third Street, where Coll had been holed up and eventually arrested months earlier for killing a child during a hit attempt on rival Joey Rao on July 28, 1931.

Police guard the London Pharmacy where Vincent “Mad Dog” Coll was gunned down, 1932. Library of Congress.

Coll’s slaying was said to have been ordered by bootlegging kingpin Owney Madden and carried out by hired guns Leonard Scarnici, Anthony Fabrizzo and Abraham “Bo” Weinberg. Scarnici later admitted to the crime before he was electrocuted at Sing Sing prison for the 1933 murder of a police detective.

Just five months before his murder, Vincent Coll (July 20, 1908–February 8, 1932) was approached by Mafia boss-of-all-bosses Salvatore Maranzano to kill Charlie Luciano. That plan did not quite work out (see Maranzano, Salvatore, below).

COLOMBO, JOSEPH, SR.

Columbus Circle, West Fifty-ninth Street at Central Park West

On Monday, June 28, 1971, mob boss Joe Colombo (December 14, 1914–May 22, 1978) was set to give a speech to the thousands who gathered at Columbus Circle for an outdoor Italian Unity Day rally. As Colombo was shaking hands on his way to the stage, an African American man approached the veteran mobster and said “Hello Joe,” before grabbing him by the neck and firing three bullets into his head at point-blank range.

The shooter, Jerome A. Johnson of New Brunswick, New Jersey—disguised as a reporter, with press pass and camera—was shot and killed at the scene by an unidentified gunman. Colombo was rushed to nearby Roosevelt Hospital, where doctors worked for six hours to save his life. They were successful; however, Colombo remained in a semi-comatose state until his death in 1978.

Several theories surround the motive of the shooting, which remains unsolved officially. Gangland legend has it that “Crazy Joey” Gallo was behind the murder, in hopes of taking over the family. An alternate leading theory is that fellow Mafiosi like Carlo Gambino were behind the assassination attempt. Yet another theory implicates the U.S. government.

D’AQUILA, SALVATORE

211 Avenue A, at East Thirteenth Street

In the early evening of October 10, 1928, “just as the [street] lamps were being lit,”135 Prohibition-era Mafia boss Salvatore “Toto” D’Aquila met his maker in a hail of bullets while standing beside his car on the corner outside this address.

The murder put to rest a long-standing feud with Giuseppe “the Boss” Masseria, which dated back to at least 1922. D’Aquila was the top guy in the Italian underworld until Masseria began moving in on the gangster’s bootlegging territory with the help of men like Giuseppe Morello, Charlie Luciano and Vito Genovese.

When D’Aquila was killed, Masseria declared himself “boss of bosses,” a title he would hold for about three years before being murdered himself.

DIBONO, LOUIS

Former Site of the World Trade Center

At 3:00 p.m. on October 4, 1990, a parking attendant of an underground garage at the World Trade Center discovered the body of sixty-three-year-old Louis DiBono lying across the front seat of his 1987 Cadillac. The three-hundred-plus-pound construction contractor and Gambino crime family member had been shot three times in the head.

Ten months before the murder, authorities recorded a phone call between Gambino boss John Gotti Sr. and an associate. In the conversation, Gotti said of DiBono, “He’s gonna die because he refused to come in when I called…He didn’t do nothing else wrong.”136

Mafia turncoat Salvatore “the Bull” Gravano later testified that Gotti had targeted his underling because he felt disrespected.

Twenty-nine years later, in March 2009, mob hit man Charles Carneglia was found guilty of murdering four men over three decades, including Louis DiBono in 1990. Carneglia, a Gambino soldier, was sentenced to life in prison.

GALLINA, GINO

Carmine Street, near Varick Street

Bronx-born Gino Gallina was a former New York assistant district attorney turned high-profile lawyer who had defended some of the most influential gangsters of the 1960s; however, his intimate relationship with the mob may have cost him his life.

Gallina served in the district attorney’s office from 1965 through 1969 before taking on such infamous clients as Genovese crime family members and “American Gangster” Frank Lucas. According to at least one informer, Gallina was a successful defender because he passed on sealed information to his clients, which led to the murders of several witnesses (though these accusations were never proven).137

Gallina was accused in 1975 of being involved in an international heroin-trafficking ring and named as a co-conspirator in a federal trial alongside several organized crime figures; however, he was not indicted.

Whatever his relationship with the mob was, it deteriorated by 1977. On November 5 of that year, Gallina and a young female companion left a West Twenty-third Street restaurant shortly after 10:00 p.m. and headed to a downtown nightclub. As the couple was getting out of their car, parked on Carmine Street, an unidentified gunman stepped out of the shadows and shot Gallina seven times in the head and neck, in what was thought to be a mob hit. He died ninety minutes later at St. Vincent’s Hospital on Sixth Avenue. The young woman was struck with a ricocheting bullet but survived.

Shortly before his death, Gallina had testified before a Newark grand jury that he held in his possession a secret tape recording that could prove who killed Jimmy Hoffa; however, he never had the chance to produce it.

GALLO, JOEY

129 Mulberry Street

On April 7, 1972, Colombo dissenter “Crazy Joey” Gallo was celebrating his forty-third birthday with some friends at the old Umberto’s Clam House at this address when a gunman calmly walked up to the group and fired two shots into Gallo’s head as he sat at his table. Gallo attempted to chase his assailant out the front door but stumbled several times before collapsing in the street and dying. At least one “bystander” returned fire on the assassin, who was able to escape unharmed.

The Gallo party had just returned to Little Italy for a late-night meal after a night on the town, which included a Don Rickels performance at the Copacabana. Seated at the table when Gallo was shot was his new wife, Sina; her ten-year-old daughter; and several relatives and close friends.

Joe Gallo (April 7, 1929–April 7, 1972), perhaps most famously known as the suspected killer of mob kingpin Albert Anastasia, was a member of the Joe Profaci crime family. By 1960, he had earned quite a high profile among police and Mafiosi alike for his truly brazen tactics. For example, when Gallo felt that Profaci—his boss and one of the most powerful Mafiosi in America—was shortchanging his crew, Gallo simply kidnapped Profaci’s top four men (and attempted, but failed, to kidnap the boss himself).

The Gallo brothers—Larry, Albert and Joe—along with a dedicated crew of followers, had initiated what would become known as the Gallo-Profaci War. After a few years of upheaval within the family, the war died down when Gallo was sent to prison in 1964 on charges of extortion. When released in 1971, Joey Gallo demanded what he felt was owed from the Profaci organization—only by this time, Joe Profaci had died and the new boss was Joe Colombo, who had no intention of paying Gallo reparations.

129 Mulberry Street today. Courtesy of Shirley Dluginski.

While in prison, Gallo formed relationships with black gang members and is said to have been one of the first to realize the value of incorporating urban street gangs into the Mafia’s illegal activities. It was in fact an African American gunman who shot Joe Colombo three times in the head on June 28, 1971, in Columbus Circle. The gunman was suspected to have been working for Gallo, but no proof of a connection has ever been shown.

GIANNINI, EUGENIO

221 East 107th Street

In the early morning of September 20, 1952, the body of Gagliano/Lucchese crime family member Eugenio “Gene” Giannini was found in the gutter in front of this address with two gunshot wounds to his head. It was determined that Giannini was shot about five blocks away in front of the Jefferson Majors Athletic Club at 2173 Second Avenue. From there, two associates tried driving the severely wounded mobster to the hospital, but when they realized he had died en route, they simply dumped his body out of the car at this location and fled. His sixteen-year-old son identified the body.

East 107th Street today. Courtesy of Shirley Dluginski.

Upon investigation, it turned up that Giannini, a Calbrian immigrant, had been working as an informant for the FBI. According to the 1969 testimony of Joe Valachi, the orders to kill the forty-two-year-old turncoat—who shot and killed a police officer in 1934—came from the very top, meaning the exiled Charlie Luciano, who told Vito Genovese that the doomed mobster had been “talking to the junk agents [the Federal Bureau of Narcotics] for years,” and “he had to be hit.” Valachi was given the contract to kill Giannini, who in turned recruited his sister’s son, twenty-five-year-old Fiore Siano, and two other up-and-coming gangsters, Joseph and Pasquale “Pat” Pagano.

According to Valachi, he drove the getaway car, and Siano did the shooting.

GIORDANO, JOHN

100 East Seventy-seventh Street

On the evening of April 11, 1995, fifty-five-year-old Gambino capo “Handsome Jack” Giordano paid a visit to ailing fellow mobster Louis DiFazio, a patient of the Lenox Hill Hospital at this location.

At 7:19 p.m., Giordano left the hospital and and set out toward a dark blue 1994 Chrysler sedan, parked in front of the hospital on Seventy-seventh Street near Park Avenue. As he was climbing into the passenger side of the vehicle, a slow-moving car crept by and fired a barrage of bullets at the mob leader, hitting him three times. One of the bullets severed Giordano’s spine. He survived but was paralyzed from the waist down.

Giordano—who ran his crew out of De Robertis Pasticceria—was a close and trusted associate of John Gotti Sr. During the “Teflon Don’s” 1990 federal racketeering trial, Giordano visited his boss regularly for moral support, and the pair often had coffee together during breaks.

Investigators later theorized that the shooting grew out of a dispute over a loan-sharking debt, and DiFazio had perhaps set Giordano up. A Bronx man name Ernesto Rodriguez was allegedly paid $50,000 to carry out the hit.

LATINI, BRUNO

Tenth Avenue and West Forty-ninth Street

On December 25, 1971, the lifeless body of mob associate Bruno Latini was found inside his car in the parking garage at this location. The victim, whose brother was Gambino capo Eddie Lino, had just left a restaurant he owned on Eighth Avenue, only four blocks from the crime scene.

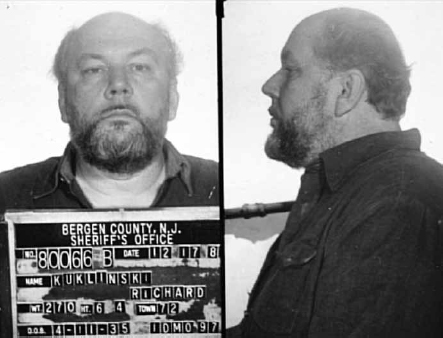

According to The Ice Man: Confessions of a Mafia Contract Killer by Philip Carlo, the triggerman was the “Ice Man” himself, Richard Kuklinski—the notorious three-hundred-pound, Polish/Irish American hit man who claimed to have murdered over 250 men on behalf of the New York and New Jersey mob over four decades.

The murder of Latini may have been personal, however. During an interview at Trenton State Prison, Kuklinski allegedly admitted to Carlo that he killed the restaurateur “out of principle.” According to the Ice Man, Latini owed him $1,500 and refused to pay, feeling his mob connections would shield him.

Richard “the Iceman” Kuklinski mug shot, 1986.

After the Kuklinski family celebrated Christmas Eve dinner at their New Jersey home on the night of the murder, Richard snuck out and drove to Manhattan looking for the man who had been avoiding him. He tracked Latini to the parking garage at this location, where the would-be victim was getting into his car. Latini invited Kuklinski into the vehicle to talk about the situation, but when Latini refused to fork over $1,500, the Ice Man pulled out a .38-caliber revolver and shot his victim two times in the head at close range. Kuklinski then took $1,500 from Latini’s wallet and returned home to his family; he was never charged with the murder.

LUCIANO, CHARLIE

Sixth Avenue and West Fiftieth Street

Charlie Lucky claimed he was abducted at this location on October 17, 1929, by three men who forced him into the backseat of a car, beat him and stabbed him several times in the back. The gangster claims he blacked out after being stabbed and woke up on the side of a road in Staten Island.

Luciano never identified his assailants, and several theories have since emerged, including one that law enforcement agents may have been behind the attack. This theory is based on the fact that no other person in history has ever been “taken for a ride” and lived to tell about it. Some believe the incident was an attempt to either shake up the rising mobster or gain information.

MADONIA, BENEDETTO

743 East Eleventh Street

On the morning of Tuesday, April 14, 1903, the body of Benedetto Madonia, a Sicilian immigrant living in Buffalo, New York, was found stuffed inside of a wooden sugar barrel on the sidewalk in front of this address.

The victim, whose throat was stabbed repeatedly with a stiletto, matched the description of a man that the Secret Service had observed in the company of the Morello gang in the days leading up to the murder. Acting in concert with local authorities, eight Morello gang members were rounded up on April 15 in a coordinated sting—all were armed with revolvers and daggers and put up a fight but were overpowered by police in the vicinity of the Bowery. Four others, including Giuseppe Morello, were picked up soon after and thrown in jail in lieu of a hefty bail. In the pockets of Morello and gang member Tommaso Petto when arrested were cigars of a “peculiar brand,” which were also found in the pockets of the victim. This and the testimony of three Secret Service agents was enough to hold the gang on suspicion of murder.

In Petto’s possession were a large-caliber revolver and a stiletto that police suspected might have been used in the murder. They also found a pawn ticket from the Collateral Loan Company at 278 Bowery—for a watch belonging to the victim. When investigated, the broker’s description of the person who had pawned the watch matched Petto’s; he had purchased the timepiece for one dollar.

A rare image of Benedetto Madonia (center), two unidentified Morello gang members (left) and gang member Vito Laduca (right). Oakland Tribune, Oakland, California, May 9, 1903.

Police tried desperately to establish the victim’s identity, a motive and a definitive link to the Morellos, whom authorities called “the most dangerous band of counterfeiters that ever operated in this country.”138 Several pieces of evidence were uncovered in Giuseppe’s dingy apartment at 178 Christie Street, including a letter written to the gang leader from the victim and another paper with Madonia’s name scribbled in red ink—later described as the “signal of death” by the press.139 The problem was, at the time, authorities did not know who Madonia was.

The cards began to stack up against the Corleone outfit when an identical barrel was found in the 226 Elizabeth Street basement, where police believed the murder occurred. Though the space belonged to the Dolceria Pasticceria on the first floor, there was no baking equipment on the premises (thus, there seemed to be no need for a full barrel of sugar). In fact, the basement was almost completely empty, and several hidden compartments were found. Since there was still not enough evidence to make a conviction, defense lawyers fought hard to have the gang released. Under mounting pressure, some gang members were dismissed on April 20.

Police caught a break when an anonymous letter they received was investigated, leading them to Giuseppe De Primo, a Morello gang member who was serving time in Sing Sing prison for his role in the 1902 Morristown counterfeiting ring. Famed NYPD detective Joseph Petrosino visited De Primo behind bars on March 21. De Primo told the detective that he had asked Benedetto Madonia, his brother-in-law, to visit New York to try and recover money from the Morello gang, which he felt was owed.

Later that day, Petrosino made a special trip to Buffalo to meet with Madonia’s wife (and De Primo’s sister), Lucia. She was shown a picture of the deceased and confirmed that it was her husband. Lucia Madonia explained to Petrosino that she and Benedetto were originally from Larcara Fredo, Sicily, near Palermo, and that her husband belonged to a “secret society.”140 She believed that “Giuseppe Morrellio [sic]” was part of this society, of which she did not know the name.

The day after Mrs. Madonia was questioned, Giuseppe Morello was taken from his jail cell at the Tombs prison and brought to the morgue in order to examine the mutilated body of the victim. Police hoped the experience would shock Morello into admission, but the steely thirty-six-year-old was unfazed. He was ultimately acquitted on April 23, due to lack of evidence.141

Tomasso Petto ended up taking the fall and being charged with the murder of Benedetto Madonia. However, he had somehow slipped out of custody and disappeared, resurfacing a couple years later in Pennsylvania. Petto was never convicted for the murder, and the Morello gang survived the incident relatively intact.

MARANZANO, SALVATORE

230 Park Avenue

Short-lived but influential “boss of all bosses” Salvatore Maranzano (July 31, 1886–September 10, 1931) rose to power during the violent 1930–31 conflict between Sicilian Corleonesi and Castellammare Mafia clans of New York City, in what is known as the Castellammarese War.

Hailing from Castellammare Del Golfo, Maranzano inherited what would become known as the Bonanno crime family in July 1930, after interim boss Vito Bonventre was murdered during the war with Giuseppe Masseria’s Corleone organization.

The Brooklyn-based Castellammarese outfit’s previous leader, Nicholas Schiro, simply fled the city in 1930, when presented with the choice of fighting Masseria or paying an embarrassingly large tribute. When successor Bonventre was removed from the picture a few months later, forty-five-year-old Maranzano stepped up to the plate and proved to be no pushover.

With the help of young Charlie Luciano and others, the Castellammarese War ended on April 15, 1931, when Masseria was gunned down in a Brooklyn restaurant. Big changes took place in the American Mafia, largely due to the efforts of Salvatore Maranzano. It is believed that this period is when the current hierarchical structure of the Mafia was incorporated, said to be based on Cesar’s Roman military. Several contemporary Mafia codes were also established during this time to prevent the inner prejudices and wanton violence that had plagued the Italian organizations for three decades and inhibited the Mafia’s full money-generating potential.

During this restructuring, Maranzano officially established the “Five Families” of the New York Mafia and declared himself capo di tutti capo.

As progressive as Maranzano was, he was still too restrictive and Old World for the younger, Americanized Mafiosi, who didn’t care much about traditional Italian codes and rituals. Most of the Mafia by this time was made up of first-generation Italian Americans or immigrants who had arrived in the United States at a very young age. Growing up in the cradle of America’s melting pot, many from this new generation of mobsters did not carry the same prejudices toward non-Italians when it came to business opportunities, nor did they care about seemingly fatuous wars between provinces.

Maranzano sensed that dissent was growing and decided to make a preemptive strike against the person he thought posed the greatest threat to his throne: Charlie Luciano.

Thinking one step ahead, Luciano sent four men disguised as police detectives to Maranzano’s office on the ninth floor of this address on September 10, 1931. The four men overpowered the fiesty Maranzano, who fought back but ultimately fell to multiple knife and gunshot wounds. The killers actually passed the man hired to kill Luciano in the hallway on the way out. It was Vincent “Mad Dog” Coll, who was told that there had been a raid and fled.

MASSERIA, GIUSEPPE

82 Second Avenue

On the morning of August 8, 1922, rising boss Giuseppe Masseria was ambushed by two gunmen while leaving his home at 80 Second Avenue. The first few shots barely missed the wiry gang leader, who fled into a shop at this location before returning fire. With bullets depleted, the gunmen ran across Second Avenue to a waiting getaway car on the corner of East Fifth Street.

As the car sped East toward the Bowery, the would-be assassins met a blockade of International Ladies Garment Workers’ Union members, who were just let out of a meeting. The speeding car plowed through the crowd and shot randomly as people panicked. Six people were hit, and two were killed. The gunmen sped away.

Investigating police found Masseria in his apartment totally unscathed, except for two bullet holes through his straw hat.

MORELLO, GIUSEPPE

352 East 116th Street

Sentenced to a twenty-five-year prison term in 1910 for counterfeiting, La Cosa Nostra patriarch Giuseppe Morello’s term was commuted, and he was released only a decade later, in 1920. Morello looked to reestablish his position at the top of the Mafia food chain. However, by this time, the game had changed dramatically, and those in power had no intention of turning over their operations. Eventually, Morello may have decided that if he couldn’t beat them, he would join them, and he allied himself with Giuseppe Masseria.

352 East 116th Street today. Courtesy of Shirley Dluginski.

On August 15, 1930, Morello, now going by the name “Peter,” became one of the first victims of the Castellammarese War. Masseria’s new adviser was gunned down in his office on the second floor of this address when two unidentified men burst through the door. He was shot five times and died on the scene. Associate Joseph Perriano leaped out the window with a bullet wound to the chest and died before paramedics could arrive. Another man, Gaspari Pollaro, survived the attack but was in critical condition. The killers were never identified.

PERSICO, ALPHONSE

320 East Seventy-ninth Street

On April 11, 1972, just four days after the murder of “Crazy” Joey Gallo, Alphonse “Little Allie” Persico (older brother of Colombo family boss Carmine Persico), his son and a bodyguard stepped into the former Neapolitan Noodle restaurant at this address for a meal. While the party waited at the bar for a table, a man in a shoulder-length black wig walked in behind them, ordered a scotch and water and threw a ten-dollar bill on the bar.

After a few sips, the man pulled out two pistols, sprung around and began firing in the direction of where Persico had been standing—only by that time, two innocent businessmen named Sheldon Epstein and Max Tekelch had taken the gangster’s place. They were both killed in a hail of nine bullets, while Persico and his party were safely seated in the back dining room. The gunman escaped in a getaway car.

This was at least the fifteenth gangland slaying in New York City in the fourteen months since Joe Colombo was shot in Columbus Circle.

SCHIFF, IRWIN

1452 Second Avenue, between 75th and 76th Streets

On the evening of August 8, 1987, 350-pound multimillionaire businessman Irwin “Fat Man” Schiff was dining with a group of twenty friends at the Bravo Sergio Restaurant at this address, when a man in a dark suit casually walked in through a side door and approached Fat Man, firing two bullets into the victim’s head before fleeing from the scene. Speculation about a mob connection immediately grew, though investigators initially had a tough time even figuring out who Schiff was.

As the case developed, a story unfolded that grabbed headlines for several weeks. It turned out that the fifty-year-old victim, who had no verifiable income, led quite an extravagant life. He drove antique Rolls-Royces, owned a $500,000 speedboat, lived in a $13,000-a-month penthouse at 415 East Fifty-fourth Street, dated beautiful models and mingled with celebrities at the finest restaurants, casinos, hotels and nightclubs in the world.

On paper, Schiff was the president of the Queens-based Construction Coordinators Corporation. However, that company had neither a telephone number nor an office. It was incorporated in 1984 using a post office box.142

Authorities eventually linked Schiff to $70 million in illegal financial transactions. He was convicted of writing fraudulent checks in 1962 and pleaded guilty to tax evasion in 1977. As witnesses came forward and tips began to pour in, speculation grew about Schiff being a mob loan shark. Eventually, a link was established between Schiff and mob boss Louis “Bobby” Manna, who allegedly ran a New Jersey–based Genovese crime family at the time.

Only two days after the murder, FBI surveillance at Casella’s Restaurant in Hoboken, New Jersey—former headquarters of the Manna crew—picked up a conversation between retired Hoboken police officer Frank “Dipsy” Daniello and Martin Casella, restaurant owner and Manna lieutenant. In the tapes, the pair was overheard discussing the murder. Daniello said of the gunman, “It takes guts though to do it like that. This kid is a—” Casella interrupted, “Stone killer.”143

Three days before the murder, another conversation was recorded between two unidentified patrons of Casella’s Italian Restaurant. One man asked, “You wanna hit him?” A second man replied, “We’ll do him good at night. Bobby Manna didn’t like CC.” According to the government, “CC” was the mob’s code name for Irwin Schiff.

FBI surveillance also picked up a conversation between Casella and Manna himself, plotting to kill Gambino boss John Gotti Sr. and his brother, Gene Gotti. “You know, this should be good and fast if it’s John Gotti,” Manna was heard saying.144

The feds allegedly warned Gotti of the assassination plot and eventually rounded up Manna (who had an apartment at 130 West Houston Street), Casella and four associates, charging them with extortion, loan-sharking, labor racketeering and murder.

Michael Chertoff, then first assistant United States attorney for New Jersey, claimed that Manna, who was described as the third-ranking member of the Genovese crime family, planned the killing of Irwin Schiff, and associate Richard “Bocci” DeSciscio was the man who pulled the trigger.

A lengthy fifteen-week trial began on March 7, 1989. On April 17, a legal secretary who lived above the Bravo Sergio Restaurant bravely picked forty-two-year-old DeSciscio out from the witness stand and placed him at the scene of the murder. Over the next two months, several witnesses took the stand, including Genovese soldier turned state’s witness Vincent “Fish” Cafaro and the thirty-three-year-old blond model with whom Schiff was dining on the night of the murder.

On June 26, 1989, Mana, Casella and DeSciscio were convicted of murder and the conspiracy to assassinate the Gotti brothers. Three others were convicted of various racketeering and conspiracy charges. On September 26, 1989, Manna and Casella were sentenced to eighty years behind bars, while DeSciscio received a seventy-five-year sentence—essentially life in prison, since none of the defendants is eligible for parole until 2049.

During the trial, it was discovered that Schiff had received at least $10 million in payments from the Luis Electric Contracting Corporation of Long Island City, Queens, which had secured more than $50 million in sweetheart public contracts in just a decade—including a $10 million deal to wire the new Jacob Javits Convention Center (655 West Thirty-fourth Street) in the late 1970s.

An exact motive for the killing of Irwin “Fat Man” Schiff is unclear to this day, though in August 1987, federal law enforcement officials claimed that Schiff was leading a double life by working as an FBI informant.145

SLIWA, CURTIS

113 Avenue A

In the early morning of June 19, 1992, the high-profile leader of the Guardian Angels was on his way to work at WABC radio in Midtown, where he hosted a talk show, when he exited Ray’s Candy Store at this address and jumped into the backseat of a cab. As the taxi began to speed off, a man hiding in the front seat popped up and opened fire on Sliwa, who managed to tumble out of the moving vehicle about a block away with bullet wounds to his leg and groin.

This brazen attack on Curtis Sliwa (March 26, 1954– ) was the second in as many months. A cast from the thirty-eight-year-old’s broken wrist had just been removed; the wrist injury was sustained in a baseball bat assault on April 23 at the same location.

A turncoat Gambino soldier named Joseph D’Angelo later confessed to being the driver of the cab and implicated that John Gotti Jr. was behind the assault; however, three separate juries were unable to find Gotti guilty, and he was acquitted.

As of this writing, John Gotti Jr. is involved in the production of a movie based on his famous family, and Curtis Sliwa, who founded the Guardian Angels citizen patrol group in 1979, has a new battle on his hands. The veteran crime fighter is protesting the making of the Gotti movie.

TERRANOVA, VINCENZO

2nd Avenue and 116th Street

The youngest Terranova brother met his end at this location on May 8, 1922, when a shotgun blast from a moving vehicle left the veteran gangster in a pool of blood on the sidewalk. Terranova managed to fire several shots at his assassins as they sped away before dying of his injuries at the scene.

It is believed that Rocco Valenti was responsible for the murder, which kicked off a bloody three-month war between the D’Aquila and Masseria clans.

TRESCA, CARLO

Fifth Avenue at West Sixteenth Street (Lower West Side)

Carlo Tresca was the editor of a popular Italian-language, anti-Fascist newspaper called Il Martello (The Hammer), which was published at 208 East Twelfth Street.

On January 11, 1943, at 9:40 p.m., Tresca was walking near this intersection when an unidentified man approached and shot him to death. The assailant jumped into a Ford sedan (New York license plate number 1C9272, for the record), where two other men were waiting, and fled the scene.

Several theories surrounding this unsolved murder lead back to Carmine Galante, though none could ever be proven. One theory claims that Vito Genovese hired Frank Garafolo to arrange the assassination as a favor to Italian dictator Umberto Mussolini. Another theory suggests that Tresca offended Garafolo at a dinner event on September 10, 1942, and ordered the hit himself.

Galante was initially connected to the crime because he visited his parole officer the same day Tresca was killed—in the same automobile the murderers used in their getaway. He was arrested three days later, but lack of evidence prevented his prosecution.

VALENTI, UMBERTO “ROCCO”

East Twelfth Street at Second Avenue

On August 11, 1922, just three days after a failed hit on Giuseppe Masseria outside 82 Second Avenue, Valenti was invited to a “sidewalk meeting” on the busy corner of East Twelfth Street and Second Avenue, just steps from John’s Restaurant, under the veil of a peace talk.

When Valenti arrived at the meeting with two bodyguards at about 11:45 a.m., he was greeted by a half dozen gunmen. Under a barrage of bullets, an eight-year-old girl and a street cleaner were wounded. As Valenti tried to jump onto a moving taxi to escape, he was shot and killed. Gangland legend says the gunman was future crime boss Charlie Luciano.

VERRAZANO, GIUSEPPE

341 Broome Street

On October 5, 1916, two men walked into the Italian Garden Restaurant located on the first floor of this address and opened fire on Morello gang member Giuseppe Verrazano. Another gunman stood guard at the door in case their victim tried to flee, but it was not necessary. Verrazano was killed at his table.

Verrazano was originally set up to be killed alongside Nicolas Morello and “Charles” Ubriaco during an ambush in Brooklyn on September 7, 1916, but he did not make the trip for some reason, so Neapolitan crime boss Pellegrino Morano sent his men after the Sicilian a month later to finish the job.

Morano was later convicted of the September 7 murders of Morello and Ubriaco and deported back to Italy by 1919.

WOLOSKY, DAVID

Northwest Corner of First Avenue and East Sixteenth Street

The body of bookie and ex-con David Wolosky, also known as David Kaye, was found by a beat cop at this location at about 1:30 a.m. on April 19, 1972. He had been shot three times in the back elsewhere and dropped off in front of the Beth Israel Hospital on this corner.

In Wolosky’s pockets were three sets of identification, several gambling slips and some loose change. He had at least ten prior arrests, including felonious assault and grand larceny.

It was the city’s eighth gangland slaying and umpteenth shooting in three weeks—including the Joey Gallo murder on April 7. Just the night before Wolosky was murdered, Thomas Graziano (nephew of the legendary boxer) had been shot in the abdomen at First Avenue and East Twelfth Street. He survived.