2

Diagnosis, Epidemiology, and Comorbidity

Psychiatry is unlike other areas of medicine with which we have become increasingly familiar, e.g. oncology (cancer) and cardiology (heart). Diagnosis in psychiatry is somewhat open to interpretation. Symptoms are observed, assessed, and evaluated against manuals containing descriptions of disorders and lists of symptoms. In neurology the brain can be assessed with sophisticated imaging equipment. In oncology we can detect a cancer. In psychiatry we have behaviors, and lots of them!

We have become used to tests for assessing all sorts of health-related problems. Blood tests can reveal a multitude of diseases from anemia to HIV, but psychiatry does not posses such diagnostic tests. If psychiatry had such tests, then perhaps there would not be a controversy over the existence of ADHD.

The diagnosis of ADHD, along with other psychiatric conditions, is open to variation and interpretation, both between individuals and across cultures. In fact the cultural context of psychiatry is of great importance. The discussions presented by Timimi and others (e.g. [32]) highlight the cross-cultural differences in diagnosis (in the case of Timimi, the difference between Iraq and the UK). The whole area of psychiatry is a minefield full of interpretation and philosophical debate, e.g. what is a disorder (see [33])?

Therefore increasing the difficulty of understanding ADHD is the fact that it is not consistently measured or evaluated the same across and within cultures. HIV is the same wherever in the world it is detected. A cancer is a cancer if it is in England or Egypt. ADHD is ADHD in the USA, but it is Hyperkinetic Disorder (HKD) in the UK and Europe. Although the term ADHD is now commonly used in Europe, the question remains: are we discussing the same disorder?

This instability in a unified world diagnosis has had considerable impact on the recognition of ADHD, its subsequent treatment, and research.

Diagnosis is subject to change over the years, and ADHD has not remained a stable construct even within classification systems such as the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) series. Diagnosis is a developing and evolving part of psychiatry. As our understanding of ADHD increases, diagnosis can be refined and made increasingly more precise and reliable. Increased diagnostic accuracy influences research, which in turn influences diagnosis, and so the cycle continues (see Figure 2.1).

Figure 2.1 The circular relationship between science and diagnosis

A Short History of ADHD

One can be forgiven for considering ADHD as a recent disorder affecting American children, but in fact there is a long history that leads up to the current-day identification of the disorder. The genetic and evolutionary accounts of ADHD would suggest that it has been present in our species for many millennia (see chapter 5). As far back as 1798, Alexander Crichton described what is now documented as ADHD according to modern-day diagnostic criteria [34]. Medical case history has since then been littered with descriptions of children who today would gain the diagnosis of ADHD.

Heinrich Hoffmann (1845), a German psychiatrist, wrote a poem that readily identifies ADHD symptoms (as reported by [35] p. 1):

The Story of Fidgety Philip

“Phil, stop acting like a worm,

The table is no place to squirm.”

Thus speaks the father to the son,

severely says it, not in fun.

Mother frowns and looks around

although she doesn’t make a sound.

But Phillip will not take advice,

he’ll have his way at any price

He turns, and churns,

he wiggles and jiggles.

Here and there on the chair;

Phil, these twists I cannot bear.

Sharkey and Fitzgerald [34] note that in 1870 a Parliamentary act was passed that made education compulsory in Britain, and that, following its implementation, behaviors that were indicative of ADHD became increasingly more obvious. Thus a shift in society’s expectations highlighted the differences in behavior (one may wonder if our current UK educational system with its targets and SATS exacerbates the increase in ADHD diagnoses).

In the early twentieth century, behaviors that now constitute the central symptoms of ADHD were identified and systematically documented [36]. As is typical of the time, these accounts were in a language that was somewhat judgmental. George Still described 43 children who had a “moral defect in control.” He continued with a rich description of over-activity, aggression, little inhibitory volition (impulsivity), and passion, but also resistance to punishment – a familiar set of behaviors to those who look after a youngster with ADHD.

Still presented his work in London and was England’s first professor of childhood medicine; therefore the origins of ADHD should not be regarded as a fabrication of North America, but rather a UK export that has been repackaged in the USA and sold back to the UK.

All the themes presented by Still are currently central to a diagnosis of ADHD. Interestingly, Still also noted that the loss of moral control was in opposition to conformity and the good of society. This can be seen as a recurring theme: that people with ADHD (and at that time restricted predominantly to children) were somehow morally bankrupt and did not fit in to the society into which they were born. This notion can be subverted for particular arguments, e.g. those who wish to explain ADHD in terms of a changing society. Indeed ADHD has been described as an externalizing disorder that does not distress the individual concerned (unlike schizophrenia or depression), but does have a profound affect on those around them (although this is not entirely true, as individuals do suffer as a consequence of their disorder, e.g. low self-esteem). Even if we accept this position that there is a fundamental discrepancy between the individual and society, why is it that the majority of the population are able to integrate and adopt societal norms, whilst those with ADHD are unable to integrate and conform? To answer this question we have to look at the psychology and neuroscience of the disorder.

Whilst Still provided the medical community with the early descriptions of ADHD, it was a little later that the brain was truly implicated as the source of the problem. In 1917 an infectious disease, encephalitis lethargica, which translates as “inflammation of the brain that makes you tired” or “sleeping sickness,” reached epidemic proportions in Europe and North America. Adults would often display the symptoms of Parkinson’s disease after the initial infection had abated. However, some children suffered a post-encephalitic syndrome that manifest itself after the inflammation and was characterized by over-activity, lack of coordination, learning disability, impulsivity, and aggression [37]. These behaviors were clearly the result of a trauma to the brain produced by inflammation, and their recognition represented perhaps the first real acknowledgment that ADHD has a neurobiological basis. Furthermore, encephalitis lethargica demonstrates how the child’s developing brain can respond differently to an adult’s brain when exposed to infection and trauma – the developing brain is very sensitive compared to an adult’s, and the brain is not complete until the age of approximately 25 years. Thus there is plenty of time to influence neural development, for good and bad. The cause of encephalitis lethargica remains unknown, but it is at this point in time that America became interested in ADHD [37]. It must be noted that outbreaks of encephalitis lethargica cannot be considered to be of etiological significance in today’s ADHD cases. However, it did provide an understanding of some of the neural processes that are possibly involved in the symptoms of the disorder.

The notion that brain damage could lead to behavioral changes is nothing new. In early studies of the frontal lobe, damage to this area was seen to have profound effects on personality and behavior (some of which are similar to ADHD symptoms) [38]. Brain damage in this era could not be readily assessed; there were no brain scanners to look inside the skull – one had to wait until death for post-mortem verification.

Without direct evidence of brain damage, assumptions about changes in the brain had to be made on the basis of psychological transformations. Thus the early classification or concept of minimal brain damage gave way to the term Minimal Brain Dysfunction (MBD; which ADHD would fall under) after it was argued that brain damage could not be assumed from behavioral measures alone (see [39] for review). This was recently exemplified in a case study of a French civil servant in which he demonstrated that individuals can compensate for large areas of brain damage and function reasonably well [40].

In the mid-1960s, Clements defined MBD as a condition resulting in:

children of near average, average or above average general intelligence with certain learning or behavioral disabilities ranging from mild to severe, which are associated with deviations of function of the central nervous system.

[41] (p. 9)

This change in description took the scientific community away from looking at structural brain damage, to looking at dysfunction and dysregulation of neural systems and not loss of tissue.

The diagnosis of MBD continued to change and included increased reliance on behavioral traits such as hyperactivity, impulsivity, and attention [42–45]. Thus the hyperactive child was regarded to have the following features: (1) poor organizational skills, poor investment and maintenance of attention and effort; (2) difficulties in inhibiting impulsive behaviors; (3) arousal modulation inconsistent with situational demands; and (4) a need for immediate reward [46]. This reconceptualization of the symptoms changed the American Psychiatric Association’s (APA) classification system from the DSM-II (2nd edition, 1968) as “hyperkinetic reaction of childhood” to “attention deficit disorder (ADD)” in DSM-III (3rd edition, 1980), and represents a shift from psychodynamic-Freudian views (bad parents – childhood trauma) to a multidimensional disorder [47]. The APA’s diagnostic change also put attention at the center of the problem, which may or may not be the case (e.g. it might be impulsivity [48] or a defect in inhibitory control [49]).

The DSM-III further subdivided the disorder into ADD with and without hyperactivity (despite a lack of evidence to support such a differentiation) [47]. In 1987 the APA published the DSM-IIIR (a revised edition) of the DSM-III. The DSM-IIIR described Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder, and the label is still in currency with the DSM-IV (2000). The DSM-IV describes the classic triad of symptoms: inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity.

Current Diagnosis

The question of when behavior is normal or abnormal is at the heart of psychiatric diagnosis. Descriptions of individual behaviors may suggest only that the child is extremely energetic, and this may not be part of a coherent cluster of behaviors that are indicative of a functional impairment that impacts upon their lives; therefore no single behavior is defining of ADHD.

ADHD symptoms have been argued to be pathological extremes of normal behavior, and can be seen to exist along a continuum that encapsulates normal behavior as well as mild, moderate, and severe symptoms [50]. For example, attention may exist along a continuum where at one extreme there is inattention as personified by ADHD, in the middle is your average child, and at the other extreme is the child who has sustained attention that cannot be shifted, as seen in some cases of autism (see [51]).

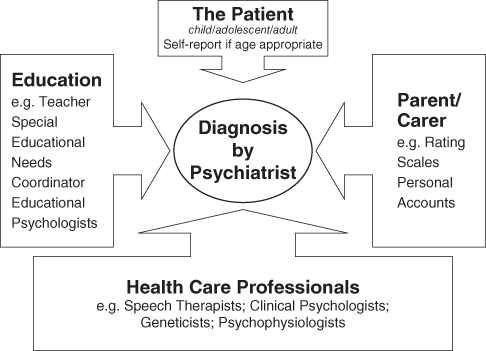

In order to diagnose someone with ADHD, there are a number of diagnostic processes to go through, referred to under the term of “differential diagnosis.” A number of people may be involved in the diagnosis (see Figure 2.2). The processes consist of weighing the probability of one disorder against that of other disorders that could possibly account for the patient’s symptoms. Some processes will be those of elimination (what it is not), others of clarification (e.g. rating scales etc.) or severity.

Figure 2.2 The input needed to make a diagnosis comes from many agencies

The symptoms of ADHD are not always unique to the disorder. Certain symptoms may be evident in more than one condition, e.g. “Often does not seem to listen when spoken to directly” from the DSM-IV classification of ADHD may also be true for children with hearing impediments. The latter example may seem trivial, but with the many complexities of ADHD all possibilities need to be considered. It is therefore extremely important to assess the child for other problems before a final diagnosis is completed.

A number of disorders that have striking behavioral similarities with ADHD need to be ruled out (see Table 2.1) [52]. In order to rule out possible alternative conditions, part of the diagnostic process may involve blood tests (e.g. anemia, lead poisoning), genetic tests (none of which are specific to ADHD, but they can identify fragile X or Down’s syndrome [trisomy 21]); and psychophysiological tests (e.g. measuring brain waves from the scalp to detect epilepsy).

Table 2.1 Conditions that may present as similar to ADHD but are not ADHD

| Anemia | Narcolepsy | Congenital brain abnormalities |

| Epilepsy | Fetal Alcohol Syndromed | Sex chromosome abnormalitiesc |

| Fragile Xa | Sleep apnea | Hearing loss (CAPD)g |

| Sleep deprivation | Tourette’s syndromee | Neurofibromatosis |

| Lead poisoning (plumbism)b | Learning disabilitiesf | Thyroid disorderh |

| Sydenham’s chorea | Iatrogenic effects | Visual impairments |

| Miscellaneous disordersc (e.g. Klinefelter syndrome) |

a B.Y. Whitman, Fragile X Syndrome, in Attention Deficits and Hyperactivity in Children and Adults, P.J. Accardo et al., Editors. 2000, New York: Marcel Dekker, Inc., pp. 371–82.

b T.A. Blondis and J.J. Chisholm, Plumbism, in Attention Deficits and Hyperactivity in Children and Adults, P.J. Accardo et al., Editors. 2000, New York: Marcel Dekker, Inc., pp. 345–58.

c N. Roizen, N., Miscellaneous Syndromes and ADHD, in Attention Deficits and Hyperactivity in Children and Adults, P.J. Accardo et al., Editors. 2000, New York: Marcel Dekker, Inc., pp. 431–9.

d S.K. Clarren, Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorder in the Context of Alcohol Exposure in Utero, in Attention Deficits and Hyperactivity in Children and Adults, P.J. Accardo et al., Editors. 2000, New York: Marcel Dekker, Inc., pp. 359–70.

e S.E. Farrel, Tourette’s Syndrome: A Spectrum of Neuropsychiatric Disorders, in Attention Deficits and Hyperactivity in Children and Adults, P.J. Accardo et al., Editors. 2000, New York: Marcel Dekker, Inc., pp. 391–400.

f E. Tirosh, E. et al., Learning disabilities with and without attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: parents’ and teachers’ perspectives. J Child Neurol, 1998. 13(6): 270–6.

g N. Roizen, Attention Deficit in Children Who Have Hearing Loss, in Attention Deficits and Hyperactivity in Children and Adults, P.J. Accardo et al., Editors. 2000, New York: Marcel Dekker, Inc., pp. 383–90; J.R. Cook et al., A preliminary study of the relationship between central auditory processing disorder and attention deficit disorder. J Psychiatry Neurosci, 1993. 18(3): 130–7.

h R.E. Weiss and M.A. Stein, Thyroid Function and Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, in Attention Deficits and Hyperactivity in Children and Adults, P.J. Accardo et al., Editors. 2000, New York: Marcel Dekker, Inc., pp. 419–30.

Diagnosis falls under two systems: the DSM-IV and the ICD-10 [53]. In North America the diagnosis is based on the DSM-IV [54], although it is used extensively outside of the USA. The current criteria can be seen in Box 2.1, and three subtypes can be seen to emerge: ADHD-H (hyperactive-impulsive), ADHD-I (inattentive), and ADHD-C (a combination of the ADHD-H and ADHD-I). This formulation of ADHD sees hyperactivity and impulsivity as a single dimension [55]. Neither of the diagnostic manuals makes any attempt to ascribe a cause to the symptoms of ADHD; this is a deliberate decision and one that avoids the rich debate that can be had on causality.

Box 2.1 The DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for ADHD

I Either A or B:

A Six or more of the following symptoms of inattention have been present for at least six months to a point that is disruptive and inappropriate for developmental level:

Inattention

1 Often does not give close attention to details or makes careless mistakes in schoolwork, work, or other activities.

2 Often has trouble keeping attention on tasks or play activities.

3 Often does not seem to listen when spoken to directly.

4 Often does not follow instructions and fails to finish schoolwork, chores, or duties in the workplace (not due to oppositional behavior or failure to understand instructions).

5 Often has trouble organizing activities.

6 Often avoids, dislikes, or doesn’t want to do things that take a lot of mental effort for a long period of time (such as schoolwork or homework).

7 Often loses things needed for tasks and activities (e.g. toys, school assignments, pencils, books, or tools).

8 Is often easily distracted.

9 Is often forgetful in daily activities.

B Six or more of the following symptoms of hyperactivity-impulsivity have been present for at least 6 months to an extent that is disruptive and inappropriate for developmental level:

Hyperactivity

1 Often fidgets with hands or feet or squirms in seat.

2 Often gets up from seat when remaining in seat is expected.

3 Often runs about or climbs when and where it is not appropriate (adolescents or adults may feel very restless).

4 Often has trouble playing or enjoying leisure activities quietly.

5 Is often “on the go” or often acts as if “driven by a motor.”

6 Often talks excessively.

Impulsivity

1 Often blurts out answers before questions have been finished.

2 Often has trouble waiting one’s turn.

3 Often interrupts or intrudes on others (e.g., butts into conversations or games).

II Some symptoms that cause impairment were present before age 7 years.

III Some impairment from the symptoms is present in two or more settings (e.g. at school/work and at home).

IV There must be clear evidence of significant impairment in social, school, or work functioning.

V The symptoms do not happen only during the course of a Pervasive Developmental Disorder, Schizophrenia, or other Psychotic Disorder. The symptoms are not better accounted for by another mental disorder (e.g. Mood Disorder, Anxiety Disorder, Dissociative Disorder, or a Personality Disorder).

Based on these criteria, three types of ADHD are identified:

1 ADHD, Combined Type: if both criteria 1A and 1B are met for the past 6 months (ADHD-C).

2 ADHD, Predominantly Inattentive Type: if criterion 1A is met but criterion 1B is not met for the past six months (ADHD-I).

3 ADHD, Predominantly Hyperactive-Impulsive Type: if Criterion 1B is met but Criterion 1A is not met for the past six months (ADHD-H).

Reprinted with permission from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Text Revision, Fourth Edition (Copyright 2000). American Psychiatric Association.

In Europe the World Health Organization (WHO) provides the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (or ICD). The current DSM-IV classification of ADHD shares some similarities with the Hyperkinetic Disorder (HKD) of the ICD-10 (Box 2.2). Changes will undoubtedly occur in the first draft of the ICD-11.

Box 2.2 ICD-10 criteria for hyperkinetic disorders

(F90) Hyperkinetic Disorders

This group of disorders is characterized by: early onset; a combination of overactive, poorly modulated behaviour with marked inattention and lack of persistent task involvement; and pervasiveness over situations and persistence over time of these behavioural characteristics.

It is widely thought that constitutional abnormalities play a crucial role in the genesis of these disorders, but knowledge on specific aetiology is lacking at present. In recent years the use of the diagnostic term “attention deficit disorder” for these syndromes has been promoted. It has not been used here because it implies a knowledge of psychological processes that is not yet available, and it suggests the inclusion of anxious, preoccupied, or “dreamy” apathetic children whose problems are probably different. However, it is clear that, from the point of view of behaviour, problems of inattention constitute a central feature of these hyperkinetic syndromes.

Hyperkinetic disorders always arise early in development (usually in the first 5 years of life). Their chief characteristics are lack of persistence in activities that require cognitive involvement, and a tendency to move from one activity to another without completing any one, together with disorganized, ill-regulated, and excessive activity. These problems usually persist through school years and even into adult life, but many affected individuals show a gradual improvement in activity and attention.

Several other abnormalities may be associated with these disorders. Hyperkinetic children are often reckless and impulsive, prone to accidents, and find themselves in disciplinary trouble because of unthinking (rather than deliberately defiant) breaches of rules. Their relationships with adults are often socially disinhibited, with a lack of normal caution and reserve; they are unpopular with other children and may become isolated. Cognitive impairment is common, and specific delays in motor and language development are disproportionately frequent.

Secondary complications include dissocial behaviour and low self-esteem. There is accordingly considerable overlap between hyperkinesis and other patterns of disruptive behaviour such as “unsocialized conduct disorder”. Nevertheless, current evidence favours the separation of a group in which hyperkinesis is the main problem.

Hyperkinetic disorders are several times more frequent in boys than in girls. Associated reading difficulties (and/or other scholastic problems) are common.

Diagnostic Guidelines

The cardinal features are impaired attention and overactivity: both are necessary for the diagnosis and should be evident in more than one situation (e.g. home, classroom, clinic).

Impaired attention is manifested by prematurely breaking off from tasks and leaving activities unfinished. The children change frequently from one activity to another, seemingly losing interest in one task because they become diverted to another (although laboratory studies do not generally show an unusual degree of sensory or perceptual distractibility). These deficits in persistence and attention should be diagnosed only if they are excessive for the child’s age and IQ.

Overactivity implies excessive restlessness, especially in situations requiring relative calm. It may, depending upon the situation, involve the child running and jumping around, getting up from a seat when he or she was supposed to remain seated, excessive talkativeness and noisiness, or fidgeting and wriggling. The standard for judgement should be that the activity is excessive in the context of what is expected in the situation and by comparison with other children of the same age and IQ. This behavioural feature is most evident in structured, organized situations that require a high degree of behavioural self-control.

The associated features are not sufficient for the diagnosis or even necessary, but help to sustain it. Disinhibition in social relationships, recklessness in situations involving some danger, and impulsive flouting of social rules (as shown by intruding on or interrupting others’ activities, prematurely answering questions before they have been completed, or difficulty in waiting turns) are all characteristic of children with this disorder.

Learning disorders and motor clumsiness occur with undue frequency, and should be noted separately when present; they should not, however, be part of the actual diagnosis of hyperkinetic disorder.

Symptoms of conduct disorder are neither exclusion nor inclusion criteria for the main diagnosis, but their presence or absence constitutes the basis for the main subdivision of the disorder (see below).

The characteristic behaviour problems should be of early onset (before age 6 years) and long duration. However, before the age of school entry, hyperactivity is difficult to recognize because of the wide normal variation: only extreme levels should lead to a diagnosis in preschool children.

Diagnosis of hyperkinetic disorder can still be made in adult life. The grounds are the same, but attention and activity must be judged with reference to developmentally appropriate norms. When hyperkinesis was present in childhood, but has disappeared and been succeeded by another condition, such as dissocial personality disorder or substance abuse, the current condition rather than the earlier one is coded.

Differential Diagnosis

Mixed disorders are common and pervasive developmental disorders take precedence when they are present. The major problems in diagnosis lie in differentiation from conduct disorder: when its criteria are met, hyperkinetic disorder is diagnosed with priority over conduct disorder. However, milder degrees of overactivity and inattention are common in conduct disorder. When features of both hyperactivity and conduct disorder are present, and the hyperactivity is pervasive and severe, “hyperkinetic conduct disorder” (F90.1) should be the diagnosis.

A further problem stems from the fact that overactivity and inattention, of a rather different kind from that which is characteristic of a hyperkinetic disorder, may arise as a symptom of anxiety or depressive disorders. Thus, the restlessness that is typically part of an agitated depressive disorder should not lead to a diagnosis of a hyperkinetic disorder. Equally, the restlessness that is often part of severe anxiety should not lead to the diagnosis of a hyperkinetic disorder. If the criteria for one of the anxiety disorders are met, this should take precedence over hyperkinetic disorder unless there is evidence, apart from the restlessness associated with anxiety, for the additional presence of a hyperkinetic disorder. Similarly, if the criteria for a mood disorder are met, hyperkinetic disorder should not be diagnosed in addition simply because concentration is impaired and there is psychomotor agitation. The double diagnosis should be made only when symptoms that are not simply part of the mood disturbance clearly indicate the separate presence of a hyperkinetic disorder.

Acute onset of hyperactive behaviour in a child of school age is more probably due to some type of reactive disorder (psychogenic or organic), manic state, schizophrenia, or neurological disease (e.g. rheumatic fever).

Excludes:

- anxiety disorders

- mood (affective) disorders

- pervasive developmental disorders

- schizophrenia

F90.0 Disturbance of Activity and Attention

There is continuing uncertainty over the most satisfactory subdivision of hyperkinetic disorders. However, follow-up studies show that the outcome in adolescence and adult life is much influenced by whether or not there is associated aggression, delinquency, or dissocial behaviour. Accordingly, the main subdivision is made according to the presence or absence of these associated features. The code used should be F90.0 when the overall criteria for hyperkinetic disorder (F90.-) are met but those for F91.- (conduct disorders) are not.

Includes:

- attention deficit disorder or syndrome with hyperactivity

- attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

Excludes:

- hyperkinetic disorder associate with conduct disorder (F90.1)

F90.1 Hyperkinetic Conduct Disorder

This coding should be used when both the overall criteria for hyperkinetic disorders (F90.-) and the overall criteria for conduct disorders (F91.-) are met.

Reprinted with permission from the World Health Organization WHO (1992): ICD-10 : The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders : Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines. Geneva: World Health Organization.

DSM-IV vs ICD-10

Looking at the DSM-IV and ICD-10 criteria, you will notice striking similarities – which raises the question as to why we have two classification systems and which one should be used. Clearly the DSM-IV is American-based, whereas the ICD-10 is used outside of the USA. However, research, rather than clinical diagnosis per se, predominantly uses the DSM-IV because the USA as a single nation publishes the majority of work on ADHD, and the rest of the world, if it wishes to publish in prestigious US journals and have data that is comparable, needs to use the DSM-IV. There are important differences between the two classification systems which give rise to some of the discrepancies seen across studies and countries; especially when the prevalence of ADHD is measured.

In a study comparing the two diagnostic systems over a six-year period, it was found that only 26 percent of those diagnosed with ADHD (DSM-IV) also met the criteria for HKD in the ICD-10 [56]. In the large and influential MTA study (Multimodal Treatment of ADHD) in the USA (see chapter 7), which used DSM-IV criteria, only 25 percent of ADHD children met the ICD-10 criteria for HKD [57].

Thus, if the epidemiological studies are using the ICD-10, they may underrepresent the prevalence of ADHD; conversely those studies using DSM-IV may be seen to overestimate cases. Occasional media accounts state the common fallacy that ADHD is more prevalent in the USA, but it is the use of DSM-IV that means there is a higher prevalence [58]. In the UK it has been argued that there is under-diagnosis of ADHD.

The diagnostic criterion used in studies is an important variable in assessing the number of individuals who have ADHD, and of course this has a human and financial cost [59]. It has been noted that those who met the criteria of ADHD but not HKD demonstrated as many functional problems as those with the HKD [56, 60]. If we take the effect of the differing criteria to the logical extreme, then children who did not meet the ICD-10 criteria are at risk of not being referred for treatment, despite the fact that they will still have a profound functional impairment.

In a recent review of the studies looking at the prevalence of ADHD, an average worldwide prevalence rate of 5.23 percent was calculated [61], but this average was associated with a great deal of variability which was best explained by the diagnostic criteria, but also the source of information and geographic origin of the studies [62] – which of course are related to diagnostic criteria. The geographical origin of the study did not differentiate the prevalence between Europe and North America (if studies used ADHD-C, then this is similar to HKD, and also Europe does use ADHD as a label), but it did between other regions (e.g. the Middle East) [62]. A recent update of the Polanczyk et al. study [62], using new research, indicates a prevalence of 6.7 percent (my calculation from the data in their paper).

The ICD-10 criteria require that all three major symptoms (impulsivity, inattention, and hyperactivity) be present in more than one situation. The DSM-IV does not require this level of stringency for a diagnosis, and reserves the subdivisions of ADHD for a less severe form of the disorder. Thus the ICD-10 criteria for HKD corresponds to ADHD-C [63]. The exclusion criteria on the basis of other disorders is less stringent in the DSM-IV than in the ICD-10, and, given that comorbidity is extremely common, this could go some way to explain the different data obtained using the different criteria. Furthermore, the requirement for pervasiveness of symptoms across different situations is relaxed in the DSM-IV, thereby increasing the likelihood of a diagnosis [63].

To further complicate matters, a study of the practice of child psychiatrists in the UK related to ADHD found that 50 percent of them used the ICD-10 system (vs 29 percent DSM-IV), but they were more likely to use DSM-IV labels such as ADHD (43 percent of psychiatrists) rather than the ICD-10 label of HKD (7 percent) [64]. Therefore, the language used in describing the disorder does not necessarily arise from the diagnostic criteria used – adding to the confusion.

The ICD-10 criteria, unlike the DSM-IV criteria, do not include reference to the social impairment or disability as a result of ADHD [65]. This may seem a trivial point, but the ICD-10’s focus on attention and impulsivity does not give justice to the impairments in daily living that these symptoms can cause. In fact when you look at the ICD-10 criteria it is somewhat difficult to see how these symptoms are an actual impairment. For this reason the use of another WHO tool is recommended – the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) [65]. The triad of impulsivity, attentional impairment, and hyperactivity are listed under “body functions,” whereas interacting with body functions is listed under “activities” (e.g. reading and writing) and “participation” (e.g. in education). The evidence that has been presented demonstrates that many children have comorbid learning difficulties and higher rates of exclusion from school. Using the ICF system evaluates the person as a whole and not just a set of symptoms with boxes to tick. However, the difficult task of diagnosis with cases of ADHD will require the evaluation of all aspects of the individual, despite the lack of wider focus beyond symptoms as characterized in the ICD-10. As Professor Eric Taylor of the Institute of Psychiatry states, “diagnosis is easy only if it is done badly” [63] (p. 17).

Is ADHD Real?

The question surrounding ADHD as a legitimate disorder, or just a fabrication of psychiatry, is subject to intellectual and populist arguments. The populist arguments are very selective with their evidence; the intellectual arguments take on a rather more philosophical tone.

The evidence is in general supportive of a claim that ADHD is a real and valid disorder [66–67]. The tools of the DSM-IV and ICD-10 are reliable and valid. What the psychiatric manuals do not provide is an etiological account of ADHD. This is a good feature. Psychiatrists may have differing views on the cause of ADHD (biochemical vs social), which does not impinge upon the identification of the disorder.

Despite the increasing evidence supporting ADHD as real, the popular press and indeed the many books on ADHD often adopt an anti-psychiatry stance, claiming it is either a social labeling problem or not a disorder at all [28, 68–69]. The anti-psychiatric movement is not unique to ADHD; it includes other disorders such as schizophrenia [70], but ADHD is the current focus for such critiques. I reiterate – I am in favor of such comments, when they are informed, as they generate discussion and thought. It is the bigoted and uninformed that annoy me! These latter views are often looking for a place to attribute blame and do not look at the detailed neuroscience of ADHD. The articulate and well-formed accounts do point out that the medical model provides an easier solution as it places the problem within the individual, who should then be treated; it is easier to do this than to change society and the way we live.

The use of the term “disorder” in psychiatry has been questioned and needs to be defined in comparison to order. Bolton [33] discusses disorder (and the opposite for order) as: (1) a breakdown of meaningful connections, e.g. the behavior does not appear to have a functional basis; (2) functional or structural lesions in neural processes, e.g. frontal lobes; (3) functioning below a statistical norm, e.g. deviates from the average; and (4) a deviation from what the mind was designed for in evolutionary terms. Each one of these has a substantial contribution to make to the ADHD debate and the view of it as a disorder.

Wakefield bridges the gap between those who see ADHD as a biological disorder and those that see it as a contextual problem when he describes disorder as lying

on the boundary between the given natural world and the constructed social world; a disorder exists when the failure of a person’s internal mechanisms to perform their functions as designed by nature impinges harmfully on the person’s well-being as defined by social values and meaning. The order that is disturbed when one has a disorder is thus simultaneously biological and social; neither alone is sufficient to justify the label disorder.

[71] (p. 373)

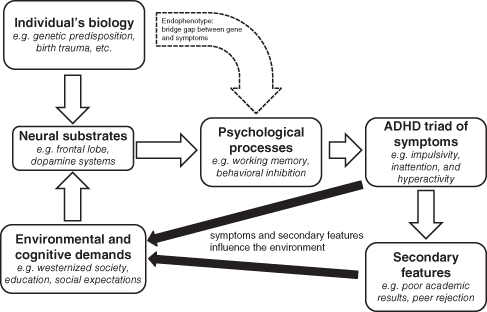

This perspective has to some extent been operationalized in the DSM-IV. In Figure 2.3 the interactions can be seen between biology and social context in the diagnostic scheme.

Figure 2.3 The role of biological, social, and psychological factors in the manifestation of the triad of symptoms seen in ADHD. Note that the symptoms feed back onto the biological mechanisms and potentially exacerbate the symptoms. Based upon [98] (p. 374)

Even though there has been good support for ADHD as a whole, there is still some debate about the validity of the DSM-IV subtypes of the disorder. Lee et al. have evaluated subtypes in a Korean sample and found that the ADHD subtypes had considerable overlap with symptoms that could not be differentiated, thereby suggesting that the subgroups are meaningless divisions [72]. In another study an analysis of the behaviors revealed that the ADHD-I and ADHD-C subtypes were readily identifiable, whereas there was little support for ADHD-H [50]. These authors continue to suggest that ADHD-like behaviors are evident in the general population, but are extreme in ADHD. The ADHD-H appears to be distinct from the other two subtypes with a diminished impact on academic and neurocognitive measures compared to the other two subtypes [67].

Adult ADHD

Despite evidence of early reports describing adult ADHD [73–74], an adult version of the disorder does not appear in the diagnostic manuals. Considering that it has taken some time for childhood ADHD to be considered a valid diagnosis [67], perhaps this should not be surprising. However, the one-time view that children just grow out of the disorder now appears to be unsubstantiated; some will grow out of ADHD symptoms, but many will not.

Reports estimate that up to 70 percent of childhood ADHD cases persist into adulthood [75] and that it affects 4.4 percent of the adulthood population [76]. The difficulty in adult diagnosis of ADHD may stem from the DSM-IV criteria in terms of being aimed at a pediatric population. The issues about adult diagnosis may be in part resolved when the new classification systems are published and possibly include adult ADHD.

Adults with ADHD are impulsive, inattentive, and restless (a variation on hyperactive) and have been argued to have the clinical “look and feel” of childhood ADHD [77]. They also have histories of school failure, occupational problems, and traffic accidents and psychosocial difficulties. Recently research has indicated that within the inmate community of a Scottish prison, 23 percent displayed ADHD and 33 percent were in partial remission, and these two groups were more involved in extreme behaviors such as aggression and violence [78]. This research and that of others promoted a response that was widely distributed by the media from the Health Minister at the time, Phil Hope:

We know that conditions like attention deficit hyperactivity disorder can contribute to people turning to crime … We are concerned that ADHD is not understood well enough in the criminal justice system so cases go unnoticed. In addition, when prisoners are released, they might be helped to find housing and employment but, if a health issue is not recognised, it can leave that person vulnerable to falling back into crime.1

Add to this the fact that there is an overrepresentation of drug abuse problems in ADHD populations and we can clearly see a big problem emerging for adults within the criminal justice system (see chapter 9). This has led Asherson and colleagues to comment that “adults with untreated ADHD use more healthcare resources because of smoking-related disorders, increased rates of serious accidents and alcohol and drug misuse” [79] (p. 5). The economic cost of not recognizing adult ADHD and not treating it are extremely large; however, the problem remains that the criminal justice system and the health service operate on separate budgets … and, as often is the case, never the twain shall meet!

The Adult Attention Deficit Disorder – UK website2 lists a set of behaviors which may be used to recognize, but not diagnose, adult ADHD: carelessness and lack of attention to detail; continually starting new tasks before finishing old ones; poor organizational skills; inability to focus or prioritize; continually losing, or misplacing, things; forgetfulness; restlessness and edginess; difficulty keeping quiet, and speaking out of turn; blurting responses, and poor social timing when talking to others; often interrupting others; mood swings, irritability, and a quick temper; inability to deal with stress; extreme impatience; taking risks in activities, often with little, or no, regard for personal safety, or the safety of others.

Paul Wender devised the Utah criteria for adult ADHD (see Table 2.2) [80–82], which provides some detail on the nature of the symptoms and how they relate to the three core domains of ADHD. Their validity and reliability as an assessment for adults are discussed on page 61).

Table 2.2 The Utah criteria for adult ADHD

| 1 Childhood History indicative of ADHD | |

| 2 Adult Symptoms: | Manifestation |

| Core requirements | |

| A Motor hyperactivity | Restlessness, inability to relax; inability to persist in sedentary activities (e.g. watching movies or TV, reading the newspaper); always on the go, dysphoric when inactive. |

| B Attention deficits | Inability to keep one’s mind on conversations; distractibility (incapacity to filter extraneous stimuli); difficulty keeping one’s mind on reading materials or tasks (“mind frequently somewhere else”); frequent “forgetfulness”; by often losing or misplacing things; forgetting appointments, plans, car keys, purse, etc. |

| Plus two of the following: | |

| C Affective lability | Usually described as antedating adolescence and in some instances as far back as the patient can remember.

Definite shifts from a normal mood to depression or mild euphoria or – more often – excitement; depression described as being “down,”“bored,” or “discontented”; mood shifts usually last hours to at most a few days and may occur spontaneously or be reactive. |

| D Hot temper, explosive short-lived outbursts | Outbursts usually followed by quickly calming down. Subjects report they may have transient loss of control and be frightened by their own behavior; easily provoked or constant irritability; temper problems interfere with personal relationships. |

| E Emotional over-reactivity | “Stressed out.” Cannot take ordinary stresses in stride and react excessively or inappropriately with depression, confusion, uncertainty, anxiety, or anger; emotional responses interfere with appropriate problem solving. |

| F Disorganization, inability to complete tasks | A lack of organization in performing tasks at home/work/school; tasks are frequently not completed; the subject goes from one task to another in haphazard fashion. |

| G Impulsivity | Minor manifestations include talking before thinking things through; interrupting others’ conversations; impatience (e.g. while driving); impulse buying. Major manifestations include poor occupational performance; abrupt initiation or termination of relationships (e.g. multiple marriages, separations, divorces); excessive involvement in pleasurable activities without recognizing risks of painful consequences; inability to delay acting without experiencing discomfort. Subjects make decisions quickly and easily without reflection, often on the basis of insufficient information. |

| H Associated features | Marital instability; academic and vocational success less than expected on the basis of intelligence and education; alcohol or drug abuse; atypical responses to psychoactive

medications; family histories of ADHD in childhood; Antisocial Personality Disorder and Briquet’s syndrome. |

Is Adult ADHD Real?

Like childhood ADHD, adult ADHD is also a controversial and hotly debated subject. The validity of adult ADHD has been supported in studies [83–85], and Faraone et al. comment that “the assessment of ADHD may be more valid in adults than in children” [83] (p. 830).

The diagnosis of adult ADHD has similar limitations to that of childhood ADHD. Most notably there is no definitive test. Furthermore, it has been noted that adults may come forward for a diagnosis after their children get one and then recognize the symptoms in themselves, which can explain a person’s history of difficulties. Clearly the diagnosis of adult ADHD could be open to abuse and used as an excuse to avoid certain activities or receive Disability Living Allowance. One Canadian study has found that students who simulated the symptoms of ADHD were indistinguishable from people who actually had ADHD [86]. Thus to avoid the potential abuse of an ADHD diagnosis by would-be actors, objective measures are clearly required and evidence needs to be accumulated from many different sources [87].

With the increasing acceptance of adult ADHD, its diagnosis and treatment, there is a growing market for the pharmaceutical companies to target. The success of treatments for adults with ADHD will require a continuity of care from child psychiatry to adult psychiatric services.

The study of adult ADHD is comparatively young in years and will continue at a rapid rate. Space does not permit a detailed analysis of adult ADHD, but those who are especially interested are directed to the book by Paul Wender’s ADHD: Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in Children, Adolescents, and Adults [81] and Russell Barkley et al.’s ADHD in Adults: What the Science Says [14].

Diagnosis and Future Criteria

Both sets of diagnostic criteria have evolved from their earlier rudimentary descriptions to their current detailed systems of classification. However, the classification systems will continue to evolve. The development and publication of both the DSM-V and the ICD-11 is just the next stage in the voyage of understanding ADHD; where it will be in 20 years could be as far away now from our knowledge as are the entries in DSM-II from the current day. Diagnosis is the foundation on which understanding ADHD has to be built upon. If we cannot identify ADHD reliably, then we cannot be confident that we are actually studying the disorder. Diagnosis is therefore important not only for clinical management but also for the academic pursuit of knowledge.

Dissatisfaction with the DSM-IV has been expressed with a keen eye on the improvements in DSM-V (e.g. [47]). In a recent editorial and paper, the following points regarding the DSM-IV were noted [2, 47]:

1 A limitation due to a lack of developmental perspective. The DSM-IV criteria do not differentiate the chronological age in which children may move from one subtype to another and do not recognize that this might have different developmental pathways [88–89].

2 A failure to acknowledge sex differences. That males are overrepresented in ADHD could be because the DSM-IV criteria are based on externalizing behavioral patterns, e.g. hyperactivity, which is less evident in females [89–90].

3 The age of onset/cut-off (7 years) lacks validity [91–92]. Not all those who have a particular subtype of ADHD meet the age criteria. Evidence suggests that a lower threshold should be used in future criteria [47].

4 The requirement for the symptoms to be present for 6 months or more has been regarded as too short and should be increased to 12 months [93]. This would account for slow transitions at school and traumatic life events that can affect behavior. However, 12 months is a long time to wait for a diagnosis, especially in the younger child, and a long time to wait for interventions. I would argue that a thorough psychiatric interview would negate this increase in time, although I accept that it is more expensive and time consuming for clinicians and requires the full cooperation of carers.

5 The notion that symptoms should be present in two or more situations maybe too stringent. Teachers and parents are often only in modest agreement. Behaviors that are problems in school may not be problematic in the home environment. An integrative approach is recommended where the different sources of information are collated and looked at as a whole [47].

6 With regard to retrospective diagnosis of ADHD in adults, it has been suggested that “acting before thinking” should be reinstated in DSM-V after its removal from DSM-IV [94].

There is general agreement that the ICD-11 and DSM-V will be very similar with regard to ADHD. A considerable amount has been learnt about ADHD since their last editions. The move to refine the diagnostic criteria of ADHD has clear implication for the individual, but also for service providers. If more people are diagnosed, then the cost of treatment will be higher [95], especially when predicting which children will respond to treatments is impossible and a process of trial and error may be needed [96].

Assessment

Assessment is the process by which a diagnosis can be arrived at by a psychiatrist. How a person gets a psychiatric referral may differ across individual cases and countries. In the UK the psychiatric referral may start with the general practitioner (GP) and end up at the local Child and Adolescent Mental Health Service (CAMHS). Assessments come from a number of sources: parent/carer interviews, individual interviews, physical examination, clinical observations, questionnaires, and other specialist input (e.g. from Occupational Therapists or Speech and Language Therapists).

Interviews with the patients themselves can be misleading. It is noted by many parents that in the novel situation of the psychiatrist’s office, the child does not exhibit the behaviors that are traditionally associated with ADHD; in fact they may appear on their best behavior! One study indicated that only 20 percent of the children interviewed in the clinic actually demonstrated the symptoms of ADHD there and then [97]. The length of the interview means that it is not likely to be repeated, thus the clinician may not actually see for themselves the behaviors that are required for diagnosis. If there were re-interviews in the following three months, for example, the second interview might contain direct examples of symptoms.

Clearly the best way to see if the child has ADHD is to observe them over a number of different occasions and settings. The novelty-inducing-best-behavior effect would be avoided by such observations. Despite some valid observational tools being available [98], they are not practical for clinical assessment [99].

The parents or carers of the ADHD child will provide a great deal of current and historical information. This information will relate to pregnancy and possible birth complications, but will continue to assess the achievement of developmental milestones, e.g. when the child first walked. The clinician will be interested in any family history of psychiatric disorders, as these indicate a higher likelihood of ADHD, especially if the fathers have a history [100].

With children, teacher input is important; after all, teachers spend a considerable amount of time with the child. Teachers, according to Professor Mark Rapport, use the word immaturity to describe 4- to 5-year-olds, and then the core areas of ADHD are described as problematic alongside general classroom disruption [98].

Interviews with informants and patients will take the form of either structured or semi-structured interviews: that is, they are not open-ended chats that can take on whatever shape they wish – there is an agenda. Semi-structured interviews provide the most reliable form of diagnosis when used with rating scales [99].

Despite evidence suggesting there are profound differences within the neuropsychology of those with ADHD, such tests do not have a role in the diagnosis of ADHD [98]: of the 56 measures used, only 5 were able to differentiate ADHD patients from non-ADHD groups [101]. Furthermore, the ecological validity of neuropsychological tests assessing executive function (which is known to be dysfunctional in ADHD) is only modest [102] and these tests are sensitive to environmental variables [103], making them unsuitable.

If we make the case that ADHD is a disorder of the brain, then surely we should be able to measure the brain to provide conclusive evidence of ADHD. Numerous studies suggest subtle, yet statistically significant, changes in the brains of those with ADHD (note I use the phrase “statistically significant” and not “clinically significant” – the clinical impact is unknown). The technology of imaging the brain, in terms of both its structure and function, is truly remarkable. Many studies make great claims that they have found the neural substrate of a particular behavior, or a difference between disordered groups and normal control groups; one should be careful about accepting, or indeed making, such claims. Moreover, the technology and evidence are not sufficiently advanced to warrant the use of brain imaging techniques in the assessment for the diagnosis of ADHD [104–105]. Indeed recent studies have been highly critical of imaging data [106].

As the clinician cannot be present in every situation and act as observer, there has to be some reliance on secondary sources of information such as parents and teachers. Increasing the reliability and validity of such information is achieved by using rating scales.

Rating Scales

Rating scales are tools of assessment, like a ruler is used for measuring length. Such scales, even with their high reliability and validity, are only an aid to the assessment process; they are not a replacement. If you complete a questionnaire to assess ADHD and fall within the catchment of ADHD scores, it does not necessarily mean that you have ADHD. Thus, you can fall either side of the cut-off point for a particular rating scale, and this alone does not mean anything serious.

A number of factors need to be looked at when assessing the utility of a scale, e.g. normative data, validity and psychometric powers. Normative data represent the normal or average score for any given question in a rating scale across various levels of performance (those with ADHD and those without ADHD). The psychometric (psycho = mind; metric = measure) properties of a rating scale are those elements that contribute to the statistical adequacy of the measure in terms of reliability and validity. The validity of a rating scale is assessed by whether it is able to measure meaningfully the constructs of ADHD. A reliable measure is measuring something consistently, but not necessarily what it is supposed to be measuring (that is the validity). Ultimately this whole process is about having confidence in what are we measuring: is it real and do we get the same answers over time? The design and evaluation of psychometric tests and rating scales is a business in itself, and is too wide in scope to consider in-depth here. However, it is important to note the strengths and weakness of the scales, but also the structural position on which the scales are based (e.g. are they based on the DSM-IV criteria?).

ADHD rating scales: children

SNAP-IV, SKAMP, and SWAN

The Swanson, Nolan, and Pelham (SNAP) questionnaire [107] has been revised into the SNAP-IV and is based on the symptoms listed in the DSM-IV (see [108] for a review). The SNAP-IV is a questionnaire for parents and teachers. The final 10 questions on the SNAP-IV are those from another Swanson rating scale, the SKAMP [109], which looks at the manifestation of symptoms in the classroom. It is more appropriate for research than diagnosis, such as in the MTA study [110–111]. However, its extensive use in research is not hampered because of the use of control groups [112].

The SWAN (Strengths and Weaknesses of ADHD Symptoms and Normal Behaviour) is a modification of the SNAP-IV (see [113–114] at ADHD.net) aimed at reducing the over-identification of children with ADHD behaviors. It is free at ADHD.net.

ADHD Rating Scale IV (ADHD RS IV)

Like the SNAP-IV, the ADHD RS IV is also linked to DSM-IV criteria and completed by parents and teachers [115]. Unlike the SNAP-IV, it has established normative data with age bands and sex as factors, plus validity and reliability have been established [112] and can make a useful contribution to clinical diagnosis [111].

Conners’ Rating Scales – Revised (CRS-R)

The CRS-R is perhaps one of the most popular and well established of the ADHD rating scales to be completed by parents and teachers and is based on the DSM-IV criteria. There are also long and short versions of the scales. There is good evidence for the CRS-R being a valid and reliable rating scale [112] and the normative data can be looked at within sex and age bands.

The Conners–Wells’ Adolescent Self-Report (CASS) is obviously for adolescents [116] but has been suggested as appropriate for children as young as 7 [86]. It differs slightly from the CRS-R and includes problems associated with adolescence such as conduct, the family, emotions, and anger. The CASS also appears to be reliable and valid [112].

The Conners’ Global Index (CGI) addresses general behavioral pathology in 3- to 17-year-olds and is not specific to ADHD.

The IOWA Conners’ Teacher Rating Scale [117] is a short 10-item scale and is again more of a research tool rather than diagnostic tool [111]. The very limited number of items and the lack of normative data represent the main limitations with this scale [112].

Vanderbilt ADHD Teacher and Parent Rating Scales (VADTRS and VANPRS)

The VADTRS and VANPRS [118] are similar to the CRS-R and SNAP-IV scales in as much as they use the DSM-IV criteria and are aimed at teachers and parents. The scales can account for age and sex of the child and have good psychometric powers, which means that they could be used in the assessment of ADHD [112].

ADHD Symptoms Rating Scale

The ADHD Symptoms Rating Scale is aimed at parents and teachers [119]. This scale is not dependent on the DSM-IV classification of symptoms, but instead uses many sources to identify ADHD; despite this it is consistent with the DSM-IV diagnosis [112].

Attention Deficit Disorder Evaluation Scale – Second Edition (ADDES 2)

The ADDES 2 is a revised version that has a parent [120] and a teacher version [121] and is based on DSM-IV criteria. Normative data can be looked at in terms of age and sex and it correlates with other well-established scales [112].

ACTeRS – 2nd Edition

The ACTeRS-2nd Edition is an 11-item scale based on DSM-IV criteria for teachers, parents, and self-report [97]. Normative data are uncertain, making its applicability somewhat limited, hence its infrequent use [112].

Brown Attention-Deficit Disorder Scales for Children and Adolescents (BADDS)

Unlike many other rating scales, the BADDS rating scale, by the clinical psychologist Thomas Brown at Yale [122], does not use the DSM-IV as its reference point. Instead it uses a more theoretical and research-based approach, most notably the theoretical approach that implicates executive functioning, which Brown himself presents [123]. The BADDS is worded differently for different age groups and includes parent, teacher, and, when appropriate, self-report measures. Such changes in the wording of questions are extremely important so that the target population can participate fully and is not alienated by technical quasi-medical terminology. Its use has been limited to mainly research studies [124], but it does correlate well with other rating scales and established tests of executive function. According to Collett et al., “the BADDS may detect nuances of ADHD that are not reflected in DSM-IV-based scales. Therefore, the potential utility of the BADDS is high”; and the BADDS “has a unique niche in its considerable potential for elucidating the specific neuropsychological deficits underlying, or areas of difficulty associated with, ADHD” [112] (p. 1032).

The Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL)

The CBCL is not an ADHD rating scale, but a more broader, 118-item questionnaire [125] that assesses 120 emotional, behavioral, and social problems. It is well established and there is a large cohort of normative data; the most recent has found convergence of 20 differing societies for the attentional subscale [126]. It is a screening tool which serves to identify potential problems, but not to track changes. There are DSM-IV-oriented subscales which address aspects of ADHD as well as comorbidities.

The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ)

Like the CBCL, the SDQ is a general screening questionnaire [127] that is better at detecting inattention and hyperactivity [128]. The normative data are extensive [129] and have good validity and reliability [130]. The SDQ has been used across many societies and been converted into languages from Urdu to Dutch [131–133].

Parental Account of Childhood Symptoms (PACS)

The PACS is a standardized interview-based measure that looks at children in their home [134–135]. The interviewer requires training in order to convert description into a rating [136]. It is useful in establishing a diagnosis of ADHD [137]. The fact that the PACS requires training, however, means that it is a costly exercise and therefore it is not widely used.

ADHD rating scales: adults

Not surprisingly, child-based rating scales cannot effectively be used in the adult population. Questions on hyperactivity may not be appropriate as this symptom is often seen to change over time – in truth we all get slower with age! Furthermore, the DSM-IV criteria state that symptoms must be present before the age of 7 years, with descriptions being based on a child’s world and not an adult’s. The relatively recent realization that there is a large proportion of the population with adult manifestations of ADHD and that they never grew out of undiagnosed, but retrospectively evident, childhood ADHD means that there are fewer rating scales for adults. Of those rating scales that are available for adults, the data to support their use are comparatively sparse [138–139]. The main scales are as follows.

Wender Utah Rating Scale (WURS) (see also Adult ADHD, page 53)

The WURS is a retrospective rating of childhood ADHD [80]. It uses Wender et al.’s [82] Utah criteria rather than the DSM-IV criteria. It is noteworthy that in the adult the hyperactivity component of diagnosis takes on a different form from that of the child. The child is often regarded to “be bouncing of the walls”; the adult, on the other hand, is more restless and needs occupying. The WURS has been regarded to have validity and reliability [140–142]. However there are few normative data [141], and whilst it is sensitive to ADHD, it has been argued to have poor specificity [143]. Furthermore the WURS fails to identify patients with predominantly ADHD-I [144–145]. At present it may represent a better research tool rather than a diagnostic tool.

Conners’ Adult ADHD Rating Scales (CAARS)

The CAARS is a self-report and observer-rated scale [146–147] and has validity for adult hyperactive-impulsive symptoms [148].

Brown Adult ADD Scale

There is also an adult equivalent to the BADDS (see above) with demonstrated validity and reliability [149]. The Brown ADD Scales for Adolescents and Adults include 40 items that assess five clusters of ADHD-related executive function impairments.

The Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale (ASRS)

The ASRS-v1.1 is a World Health Organization scale that measures the frequency, and not the severity, of symptoms [150]. There is some evidence for the scale having validity and consistency [138]. Somewhat surprisingly, the ASRS-v1.1 is based on the DSM-IV criteria and not the WHO’s ICD-10. Is this perhaps a realization that the DSM-IV is the dominant diagnostic tool and the direction that the ICD-11 will take?

Rating scales: summary

The ADHD rating scales (and the less specific scales CBCL, SDQ, and PACS) are used to look at behavioral maladaptations and psychopathology. There are a number of other measures that are used in assessment that are well documented elsewhere (see [151–156]).

There are a number of rating scales that are available to assess ADHD and newer ones are on their way, e.g. A-TAC, a telephone interview with parents for general childhood psychopathologies [157], and the more specific telephone interview the Child Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Teacher Telephone Interview [158].

Of all the scales available, which one is used will depend on various factors such as price and purpose. However, having looked at the rating scales and seen how they are on the whole dependent on the diagnostic classification of ADHD in the DSM-IV, it will be interesting to see how these scales will evolve to the future DSM-V system if it has important changes.

Epidemiology

The general prevalence of ADHD, and other psychiatric conditions, is somewhat dependent upon the classification system used and by factors such as the age group studied (i.e. children of a certain age, adults, males, etc.). The ICD-10 uses a more stringent set of criteria compared to the DSM-IV; thereby fewer people will be diagnosed under the ICD-10. Additionally, the continual modification of the diagnostic criteria can influence prevalence estimates. In a review of studies conducted in the USA using DSM criteria, a prevalence range of 9.1–12 percent was found using the DSM-III, which rises to 11.4–16.1 percent using the DSM-IV [159].

Is ADHD, as has been widely cited in the media, an American phenomenon that is now been exported around the world? A review of epidemiological studies reveals that ADHD goes beyond the borders of America [159], but the DSM-IV may overestimate prevalence, e.g. in Brazil 18 percent were diagnosed ADHD when using the DSM-IV vs 3.5 percent using neuropsychological profiles [160]. However, one has to be careful with such comparisons because neuropsychological testing is not a reliable indicator of the functional problems associated with ADHD and may only detect certain subtypes of the disorder [67]. We have seen earlier that how you measure ADHD influences prevalence estimates.

To place the prevalence of ADHD in context, autism has a prevalence rate of 0.6–0.7 per cent [161], and Tourette’s syndrome has a prevalence of between 0.4 percent and 1.76 percent for children aged 5–8 years old [162]. In the USA there is an ADHD prevalence rate of 11.4–16.1 percent in 8- to 10-year-olds and outside the USA there is one of 2.4–19.8 per cent (7- to 11-year-olds) [159]. These differing prevalence rates are most likely accounted for by methodological variance in assessment and protocols [163]. In the UK it was estimated that 5.3 per 1,000 were diagnosed with and treated for ADHD in 1999, with a peak at the ages 9 to 10 years old, and that this did not change over the five-year study period [164]. However, according to Eric Taylor, the prevalence rate is approximately 5 percent in primary school education [165]. Furthermore, only 1 in 10 children in a study set in Croydon, UK, who were responding highly on rating scales received a diagnosis, with parental input being the major factor in accessing medical resources [166], and, worryingly, general practitioners (GPs) were only detecting 25 percent of cases of child psychopathology, although this did rise when there was parental concern [167].

The estimates of the incidence of ADHD have important economic implications. Over-inclusive criteria may result in additional treatment costs that may be unwarranted, but more problematic is the under- diagnosis, especially of ADHD-I, in which people do not receive the support and help they need [168].

With these caveats in mind, there are some other features in the epidemiological data that warrant further mention, e.g. sex differences.

Adult epidemiology

Despite not being included in diagnostic manuals, it is accepted by many (e.g. Barkley) that there are cases of adult ADHD. Epidemiological studies have started to assess the extent of the adult ADHD, estimating a prevalence rate in America of 4.4 percent [9] and worldwide of 3.4 percent [169], although the later study found differences in the rate of ADHD as a function of the wealth of the country. Compare this with a prevalence rate in a 12-month period of 2.4 percent for alcohol dependence, 6.9 percent for depression, 0.9 percent for bipolar disorder, and 0.8 percent for psychotic disorder, e.g. schizophrenia [170], and you can see that adult ADHD is a big issue. Whilst you may consider the percentages to be small numbers, just think how many people’s lives are affected by these disorders in a UK population of 60.5 million people (Source: Mid-year population estimates: Office for National Statistics, General Register Office for Scotland, Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency 2006).

The cultural context of diagnosis

Diagnosis and thus the prevalence rates are linked to the clinician’s assessment. The clinician is part of a culture that has belief systems, morals, ethics, and ideologies that may differ from another clinician in another country. However, the cultural context goes further than just a bias that a clinician might have. The wider society, which also adopts the culture, has an important role. The role of parents and teachers within the culture can also partly define psychopathology. In an interesting study by Bathiche in the Lebanon, parents and teachers were shown vignettes of ADHD subtypes. Parents considered the ADHD-H and ADHD-C subgroups to be behaving normally. They were able to use problem behaviors labels in descriptions, but they did not consider them as negative (cited in [171]). The ADHD-I subtype was associated with problems and characterized negatively. This has led Rousseau et al. to state that “the recognition of ADHD symptoms and the labelling of distress as being deviant or pathological depend on the norms of behaviour accepted in a particular culture” [171] (p. 71). Essentially, if the symptoms of ADHD are not seen as a problem by the parents, these children are unlikely to be presented to clinicians. This then influences prevalence estimates. The impact of culture on diagnosis and psychopathology has been written about by many, but interested parties should read the excellent work of Sami Timimi [32, 69].

Sex differences

More males are identified with ADHD than females [172]. Again the classification system may have some impact on the sex ratio (see [173]). Earlier classification criteria such as the DSM-III may underestimate females as they do not meet the criteria of impulsivity and hyperactivity. Their attentional difficulties may only become apparent as they progress through school and begin to fall short of age-related expectations. The inclusion of subtypes in the DSM-IV may go some way to rectify this, with more females being classed as ADHD-I, but only as they get older.

In terms of research in ADHD, the sex difference needs to be explained. There are obvious, and less obvious, differences between males and females which may give rise to symptoms. Such studies may help with understanding etiology, but also in refining diagnosis.

Prognosis

The one question that parents of children with ADHD will want to know the answer to is: “Will they grow out of it? The mere fact that adult ADHD is becoming recognized gives a hint to the answer, but the answer cannot be a categorical yes or no. Some may just have a developmental delay [174]. Whether ADHD persists into adulthood depends on how you define persistence and what criteria you are using [75, 175]. A prospective study of ADHD children followed up after 10 years (16- to 28-year-olds) suggests that childhood ADHD is a risk factor for antisocial disorders, anxiety and mood disorders, and substance abuse disorder [176]. This cohort of ADHD patients had received treatment during the 10 years (93 percent) with only 36 percent receiving treatment in the year preceding evaluation. Furthermore, only 58 percent met the full DSM-IV criteria, but 70 percent did when a more relaxed system of assessment was used. Whilst this may appear optimistic for the person with ADHD, it is not; a substantial proportion still have problems in adulthood [177]. They clearly have a greater incidence of other psychopathologies. Whether this is a result of the ADHD symptoms, disengagement with education, discontinuation of treatment, or some other unspecified factors is not clear. The role of ADHD in crime has not gone unnoticed either, with criminal activity being linked to the ADHD-H subtype rather than the ADHD-I [178].

The evidence suggests that different aspects of ADHD change over time and that perhaps different subtypes have different developmental trajectories and impacts [88, 179].

Comorbidity – Not Just ADHD

One may consider it bad enough having ADHD, but rarely does ADHD exist on its own. ADHD is often diagnosed along with other psychiatric problems – that is, ADHD is comorbid with another disorder [108, 180]. Indeed, “comorbidity is the norm rather than the exception” [181] (p. 14). An International consensus statement from experts in the UK, USA, Canada, Israel, the Netherlands, and Germany recommended that clinicians should “not be satisfied with a single diagnosis; keep assessing to uncover likely comorbidities; accurate diagnosis is essential to improve the prognosis” [181] (p. 14). Thus it may be necessary for multiple assessments to take place that look at different disorders. Such assessments may take place at different periods of the individual’s treatment plan. It could transpire that the successful treatment of ADHD unmasks other problems, e.g. dyslexia or anxiety.

There are many common comorbidities with ADHD which have warranted dedicated reviews (see [182]). The two most common comorbidities are Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD) and Conduct Disorder (CD), which need to be accounted for during diagnosis. ODD and CD are labels to describe defiant behavior with increasing severity. ODD is where children disregard rules to a greater extent than they would with ADHD alone, even when there are many punishments for such behavior. They can be argumentative, provocative, and prone to temper outbursts. They can also be spiteful and vindictive and are easily annoyed. CD is another extreme of behavior beyond ODD. The behavioral profile of CD is more like a criminal record with arson, theft, vandalism, and other antisocial activities, which has the greatest impact on family life, whereas the hyperactive symptoms of ADHD have less of an impact [135].

Other comorbidities which can appear at different times in the person’s development include anxiety, depression, obsessive compulsive disorder, Tourette’s syndrome, substance abuse, and many more [182].

The human cost of comorbidity is easy to see, but there are other costs to understanding ADHD that should also be noted. When studying ADHD, one might not be studying a simple pure disorder. This gives rise to difficulties in assigning causality to a disorder and knowing what it is we are really looking at. Is it ADHD or something else causing a particular symptom, or are the two interacting? Given that ADHD is often comorbid, an understanding of how various disorders work together is required: what is the reason for ADHD being associated with a particular disorder, e.g. addiction (see chapter 8)?

The nature of comorbidities and the diagnostic subgroups makes the ADHD literature a complex world to navigate. Many studies use different groups with different severities, making comparisons across studies difficult, and ultimately conclusions are based on data which have limitations.

Summary

The diagnosis of ADHD is continually evolving. Future criteria will no doubt include adults, rather than a narrow focus on children and adolescents. At present there are two sets of criteria that attempt to identify cases of ADHD: the DSM-IV and the ICD-10. The use of two differing sets of criteria makes the identification and study of ADHD somewhat more difficult. Research and treatment are completely dependent upon diagnosis being accurate, valid, and reliable. However, diagnosis is limited to observation, interview, and rating scales. There is no test for ADHD. Tests of specific deficits in certain functions such as impulsivity and sustained attention are not yet able to diagnose ADHD per se; however, recent reports have highlighted that cognitive tests which are simultaneously measured with brain activity aid the support of diagnosis and provide a reference point in which treatment efficacy can be measured [183]. In the future, diagnosis may be able to embrace a more objective set of measures such as those mentioned above, and then the issue of the prevailing culture will be minimized and perhaps a greater understanding of comorbidity will be achieved.

Notes

1 http://www.guardian.co.uk/uk/2009/dec/27/adhd-prisons-mental-health-crime.