Given the dynamism of Lancashire and its people throughout the Industrial Revolution, it is not surprising that the county has produced some major politicians, businessmen, inventors, artists and so on. And amongst them have been some great characters. Some of the Lancastrians who appear in this chapter have selected themselves; others I have selected and readers may disagree with my choices.

A Leash of Prime Ministers

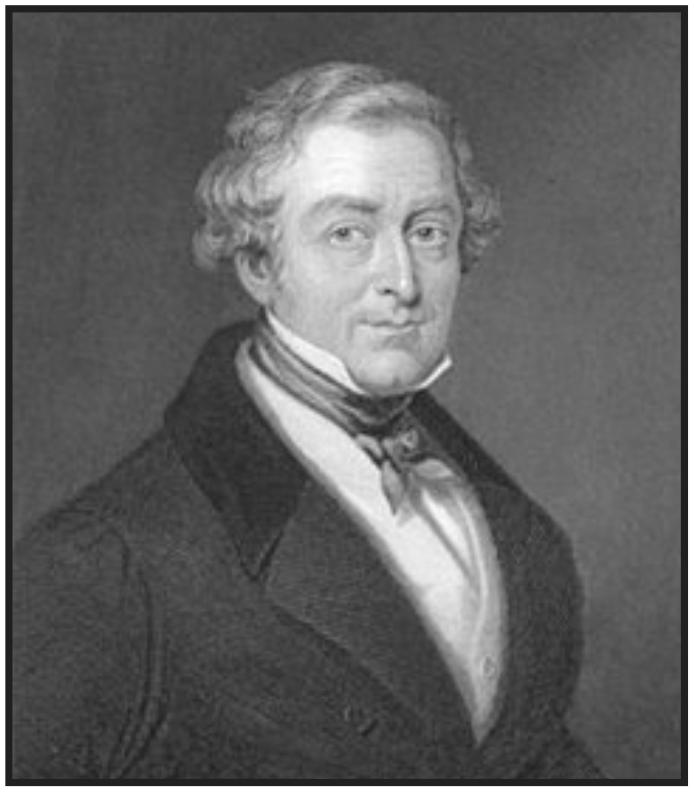

SIR ROBERT PEEL

Robert Peel was born in 1788 into a wealthy family of cotton-mill owners in Ramsbottom. Educated at Harrow and Oxford, he became a Tory MP at the tender age of 21 and rose rapidly through the ranks to become Home Secretary aged 34. In the next eight years, before the Tories lost office in the 1830 election, Peel was involved in prison reform and, especially, the formation of the police force, initially in London and then the whole of the United Kingdom. Then the police had two nicknames with the public. One, ‘peelers’, is now largely forgotten, but the other, ‘bobbies’, still continues to be used. Both of these come from Robert (Bobby) Peel.

In 1834, amidst some political turmoil, he was summoned to the Palace by William IV and asked to form a government, which he did, but his first term as Prime Minister lasted only into 1835 and he was out of office again until 1841. He was then Prime Minister for five years, and once more drove major reforms. He introduced the Mines Act, which prohibited women and children working deep underground in coal mines, and the Factory Act, which drastically reduced the hours that children could be made to work in cotton mills and other factories. These reforms were major steps in employment legislation, but were strongly opposed by some mine and mill owners.

Peel’s final reform was of the Corn Laws. These had been brought onto the statute books to protect the agriculture industry from cheap imports of cereals like oats and wheat. The consequence of this earlier legislation was that, when British production was low because of a cool wet summer and home-grown cereal very expensive (by the laws of supply and demand), the cost of imported cereal was also made artificially expensive. Poor people could not afford to buy grain to make staples like bread and oat-cake.

Sir Robert Peel was a great reforming

Prime Minister

In 1845 the situation reached its nadir in Ireland, where the price of cereals had become so expensive that the millions of crofters had become dependant on the potato for sustenance. By late autumn of that year, potato blight had destroyed the bulk of stored potatoes, and so Peel hurriedly arranged for £100,000-worth of maize and maize-meal to be shipped over from the USA. This arrived too late (in February 1846), and when it did arrive it was not very useful, for the yellow porridge produced from it was difficult to digest and resulted in abdominal pains. In 1846 Peel repealed the Corn Laws, keeping the price of edible cereals relatively low when home-grown crops failed and cereals had to be imported.

Alas for Peel, many Tory landowners disagreed with this policy, and he was forced out of office later that year. He died in 1850, and a monument to Sir Robert, the Peel Tower, was built on the moorland top at Holcombe, overlooking the Irwell Valley.

WILLIAM GLADSTONE

William Ewart Gladstone was born in Liverpool on 28 December 1809 into a family that owned a large commercial house in the city. Educated at Eton and Oxford, he was only 24 years old when he became Tory MP for Newark. The following year (1834) Sir Robert Peel made him Junior Lord of the Treasury and Undersecretary to the Colonies, and in 1841 he became Vice President of the Board of Trade. He then lost his seat at Newark, but was returned to parliament in the 1847 election as Member for Oxford University.

But then, in 1859, he fell out with the Tories and became a Liberal, quickly becoming leader of the party. In 1868 he became Prime Minister after his great rival Benjamin Disraeli. In 1874 Disraeli again became PM until 1880, when Gladstone returned to number 10 Downing Street. He lost power in the 1885 election, but retook power briefly in 1886. Then, he became Prime Minister for the last time in 1892 and gave up the post in March 1894. In all, Gladstone was a Member of Parliament for 62 years (one less than W.S. Churchill’s 63-year record)and is the only man to serve as PM four times.

Gladstone continued the social development begun by Peel. He wanted social reform and an extension of electoral franchise, and he wanted the power of the House of Lords limited. He fought for home rule for Ireland. He served through Victoria’s reign, which saw a vast expansion of the British Empire ‘on which the sun never set’, and which had large areas of the world atlas ‘painted red’. His rival Disraeli, who flattered the Queen, had Parliament grant Victoria, in his second term as PM, the title ‘Empress of India’. Victoria enjoyed the flattery and the Tories were opposed to Gladstone’s anti-Imperialist reforms.

One of Gladstone’s great plans which, alas, never came to pass was the abolition of Income Tax. He argued (rightly!) that if you lower taxes, then people have more money to spend and thus more money circulates through all strata of society. Of course, it was not long before the status of the Liberal party declined. The Grand Old Man of the Liberal Party died in 1898.

DAVID LLOYD GEORGE

But he was not the last Lancastrian to be Liberal Prime Minister. That accolade goes to one David Lloyd George who was born, not in Wales, but in Chorlton-upon-Medlock on 17 January 1863. He was son of a poor schoolmaster William George, who died when David was only 18 months old, and he and his penniless mother Elizabeth were taken in by her brother, Richard Lloyd, a cobbler and Baptist pastor in the village of Llanystumdwy, just outside Criccieth in North Wales. So David George took his uncle’s surname and became David Lloyd George.

Lloyd George has three claims to fame. Firstly, as Chancellor of the Exchequer in 1909 he founded the Old Age Pension at five shillings per week. Secondly, he was the last Liberal Prime Minister (1916-22). Thirdly, he was a great womaniser, nicknamed ‘The Goat’ on account of his penchant for tupping any woman who would let him! He died in 1945.

A Leash of Great Businessmen

ROBERT GILLOW

Robert Gillow was born in 1704 into a Catholic family living in the Fylde at Singleton. When he was 14 years old, he took up an apprenticeship in Lancaster as a cabinet maker, choosing to live and work in Lancaster, so it is thought, because his father was in the town’s jail. The young Robert then travelled to the West Indies as ship’s carpenter, and returned with one of the first quantities of mahogany brought into Britain. In 1728 he became business partner with George Haresnape and opened his first factory producing the finest of furniture. He imported the mahogany from the West Indies through the Port of Lancaster, sold much of his production to the gentry of England while reserving some to export back to West Indian plantation owners’ houses. Visit the West Indies today, and you can still see 18th century Gillow’s furniture in these houses which are now museums.

Robert Gillow died in 1772 and the business was then run by his sons Richard (1734-1811) and Robert (1745-1793). The family continued as Gillows of Lancaster into the 19th century, acquiring Leighton Hall, near Carnforth, as their home in 1827, now open to the public. But by 1897 the company needed financial help, which came from the Liverpool company of Warings, and in 1903 Gillows became Warings & Gillows.

In 1964 the company was taken over by Great Universal Stores and the main factory - on St Leonardgate close to Lancaster city centre - became the temporary home of the University of Lancaster (where I studied 1965-68!). Today Gillow fine furniture commands high prices at the major auction houses, and it is a pity that the quality fell, leading to a collapse of the company.

JAMES WILLIAMSON

James Williamson was born on 31 December 1842 to James (sr) and his wife Eleanor who had, in 1840, founded a company manufacturing coated (i.e. waterproof) fabrics.

After attending Lancaster Royal Grammar School, James went to work in the family business that produced vast quantities of oil-cloth (linoleum) floor coverings that were exported around the world. Until the 1960s most people had ‘lino’ on the floors of their rooms and, before the days of wall-to-wall carpets, lino covered the floor between rug and walls. Its great virtue was that it could be mopped without getting soggy or waterlogged. Williamson’s factory by the Lune estuary below Castle Hill was vast, covering over 20 acres, and it made him one of the most powerful and wealthy people in the country. Not surprisingly he rose rapidly through the ranks of the high and mighty, as wealth flowed in.

He was a Lancaster town councillor (1871-80) and from 1881 a justice of the peace. In 1885 he was High Sheriff of Lancashire and from 1886-95 Liberal MP for Lancaster. In 1895 Lord Roseberry recommended four of his fellow Liberals to be created peer by Queen Victoria and one of these was Williamson, who took the title of Baron Ashton of Ashton (in 1884 he had purchased Ashton Hall, by the Lune estuary between Lancaster and Glasson, now home to Lancaster Golf Club) and had established Ashton Park, on the east side of Lancaster.

For some Lancastrians it rankled that he had taken the name Ashton instead of Williamson. But nationally there was something of an uproar. The Liberals had needed funds to fight the 1895 election and it was rumoured that Williamson had handed over £4,000 (then a great deal of money). Roseberry denied that he had sold a peerage to Williamson, and Williamson did not deny handing over the £4,000, but said that the money was not for the purpose of helping fund the Liberal Party. Sleaze and politics is not, apparently, a 20th and 21st century phenomenon!

Williamson was a major employer in Lancaster and, with his rival in the manufacture of oil-cloth Storey Brothers, employed over a quarter of the male workforce of the town towards the end of the 19th century.

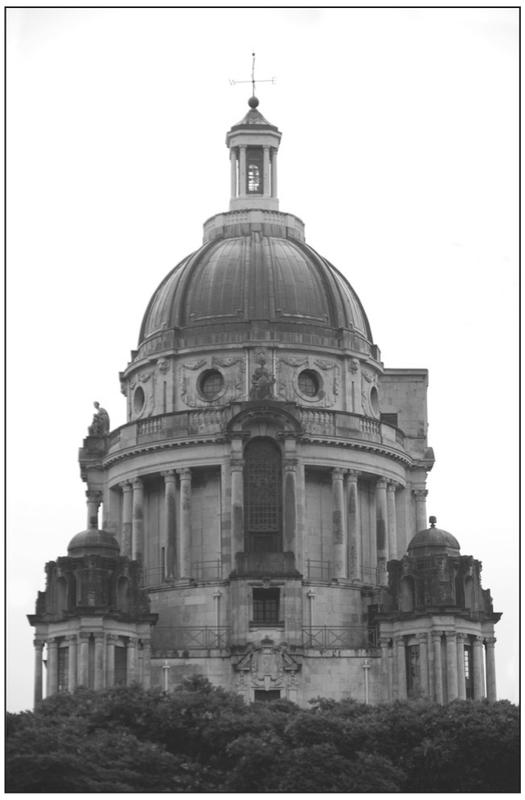

The Ashton Memorial dominates the Lancaster skyline

He funded many civic amenities and charitable causes, including the fine bronze statue of Queen Victoria in Lancaster’s Dalton Square.

There are also Ashton Houses named after him in both Lancaster Royal Grammar School and Kirkham Grammar School. However Williamson’s most visible legacy is the Ashton Memorial.

He married three times, his second wife being Jessie Hulme (married 1880). The family had already funded Williamson Park on a hill overlooking Lancaster from the east and it was there that he built a huge domed ‘folly’, the Ashton Memorial, in memory of wife Jessie. It was opened in 1909 and dominates the city skyline from the east (as from the M6) and from the west (the Lune estuary and the West Coast railway). Nicholas Pevsner, the expert of great British buildings, described the Ashton Memorial as the ‘grandest monument in England’.

WILLIAM LEVER

William Lever was born at 6 Wood Street, Bolton on 19 September 1851. He left school (Bolton Church Institute) when he was fifteen years old to work in his father’s (James) grocer’s shop, and upon reaching the age of 21 he was made a partner in the business. In those days, soap was manufactured in large blocks and grocers cut off small pieces to sell to their customers. Lever came up with the idea of manufacturing soap in small, prepackaged bars that customers could buy, at a time when the Victorian adage ‘Cleanliness is next to Godliness’ prevailed. So with his brother James, who was more of a sleeping partner, he set up a company Lever Brothers and opened a factory in Warrington to manufacture a top quality soap, Sunlight Soap.

Warrington is by the Mersey and was ideally placed for barges bringing caustic soda from local chemical works. The soda was made from common salt (sodium chloride) produced by salt mines in nearby Cheshire. The other ingredient in soap manufacture is fat, or oil, and Lever went to west Africa for this. The Belgian Congo had, until its independence from Belgium in 1960, a policy of forced labour on the native population. So there Lever established large palm-oil plantations and had the cheap oil imported via the Liverpool and Birkenhead docks. This made Lever incredibly wealthy, incredibly quickly.

His Warrington factory was too small and there was no room for expansion, so Lever purchased land on the southern shore of the Mersey estuary, close to docks through which the ingredients for making soap could be brought. There he built a new factory and an idealised village for his workers, Port Sunlight. Of course Lever, a staunch Congregationalist, could not just build homes and let his employees/residents live their lives as they wished.

He was a philanthropist who expected something in return. So anyone who worked at Port Sunlight had excellent homes, sports facilities, jobs and wages that had the edge on other similar jobs, but the workers had to agree to a strict lifestyle. Nevertheless it worked, and Lever had his obedient workforce and an increase in his wealth and status. His nannying also saw him attempting to get other soap manufacturers to join him in making soap a big monopoly, arguing that this would benefit the people who bought soap. A curious argument, for all it would have guaranteed was a nice profit for all the manufacturers!

From 1906-9 Lever was Liberal MP for Wirral, his maiden speech arguing for an Old Age Pension, paid for by the state (Lloyd George’s government brought this into being in 1909). He also fought hard for improving the rights and working conditions of workers (but not those in the Congo). In 1913 he became High Sheriff of Lancashire. In 1874 he had married Elizabeth Ellen Hulme. She died in 1913, so that when he was made a Baron in 1917 he took the title Baron Leverhulme of Bolton-le-Moors. In 1918 he served as mayor of Bolton, even though he had not served as a councillor. And then in 1922 he was made Viscount Leverhulme of the Western Isles (see below), the title being extinguished when the third viscount died without issue in 2000.

Rivington Barn is one of several old buildings in Lever’s Rivington estate, now owned by the people of Bolton

Lever was a great philanthropist. He purchased a large estate at Rivington, west of Bolton, which he left to the townspeople as Lever Park. In 1902 Samuel Crompton’s house Hall i’th Wood was financially precarious so he bought that and gave it to the town. He established the School of Tropical Medicine at Liverpool University and donated Lancaster House in London to the nation. Then he moved to the Western Isles, purchasing land and attempting to make changes that would benefit the local population. The folks of Lewis rejected his offers but those of Harris took to him and in the town of Leverburgh his name lives on. As it does also in the Leverhulme Trust, which continues his charitable work, and in Unilever (founded 1929), one of the world’s major companies.

One Wanderer

Alfred Wainwright was born on 17 January 1907 into a poor working class family in Blackburn. He left school when he was thirteen and, instead of going ‘in t’mill’ like the rest of his classmates he got a job as an office boy in the Town Hall. Whilst there he spent long evenings studying until he became a qualified accountant. Through these early years he was a keen walker, and in 1930 had saved up enough cash to take a week’s holiday in the Lake District. That was the turning point of his life. He had the means to escape from Blackburn (his qualifications) and the motivation (to walk the Lake District mountains). He took a job in 1941 in Kendal Borough Treasurer’s Office and from 1948-67 was the town’s Borough Treasurer.

Fourteen years after he had moved to Kendal and spent much of his free time walking the Lakeland peaks, he decided to produce his Pictorial Guide to the Lakeland Fells. At weekends he walked, using public transport or, occasionally, getting a lift from someone he knew to reach the mountain he wanted to climb that day; and through the weekday evenings he sketched and wrote, in his characteristic hand, every page of what turned out to be seven fabulous volumes that were published 1955-66. Having completed them, he turned his attention to the Pennine Way, his guide appearing in 1968. I used it in 1969 when I made the 270 mile trek, and it was clear that he hated much of the walk (especially the black oozy peat bogs of the southern Pennines), but the guide was perfect, especially when dense mist shrouded the higher peaks.

In 1972 he published his Coast to Coast Walk, St Bees to Robin Hood’s Bay. But of his later works, the best are his Sketchbooks, especially, for a Lancastrian, A Lune Sketchbook (1980), A Ribble Sketchbook (1980), A Bowland Sketchbook (1981) and A Wyre Sketchbook (1982). Out of print, these are now very expensive. A recent catalogue (2009) prices the Ribble volume at £95, the Wyre volume at £120 and the Bowland Sketchbook at £175; but they are delightful.

A.W., as many fell-walkers referred to him, was something of a grumpy old man, who hated the company of others when out walking, and would deny his identity when questioned. He was a single-minded, self-centred individual who would not have achieved so much had he been otherwise. Perhaps. In 1931 he entered a loveless marriage (on his part certainly) with mill worker Ruth Holden, with whom he had a son Peter. She left him in 1967 just before he retired. Then in 1970 he married Betty McNally (1922-2008) who, after A.W. had died on 20 January 1991, followed exactly what he specified in his will. He was cremated and she carried his ashes up Hay Stacks and scattered them in Innominate Tarn.

Three Great Painters

Lancashire has produced lots of good artists, and still does, as those who attend the summer exhibition of local artists in Leigh’s Turnpike Gallery will agree. But there have been relatively few famous artists.

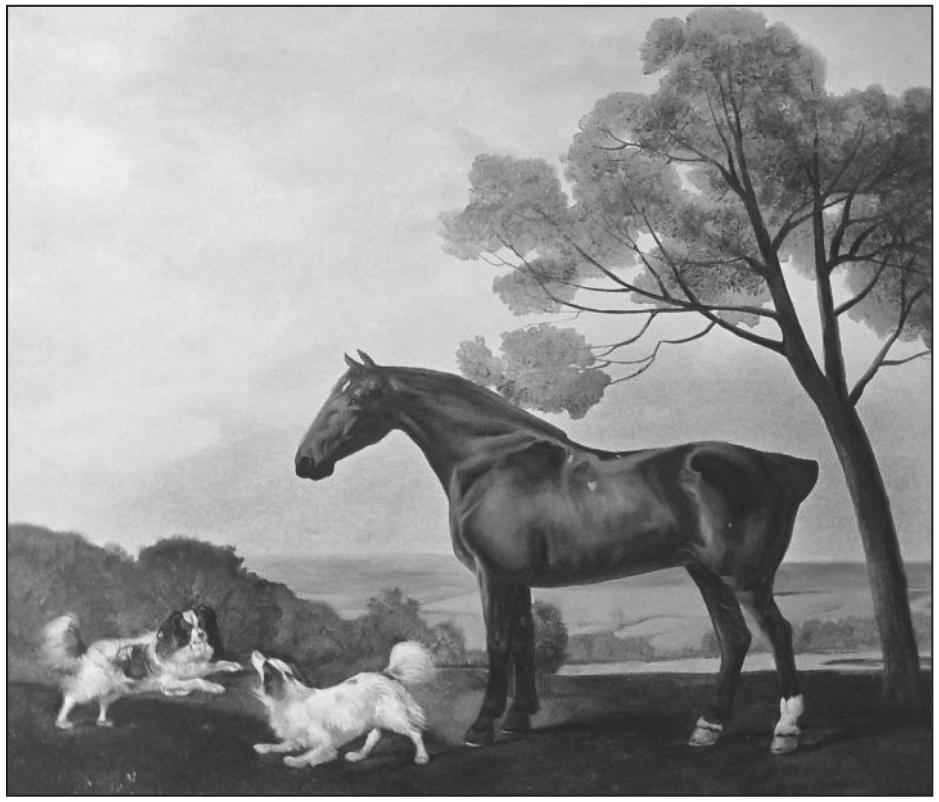

GEORGE STUBBS

George Stubbs was born the son of a leather dealer in Liverpool in 1724. After leaving school he worked for his father before becoming apprenticed in 1741 to a painter-engraver called Winstanley. He quickly gave that up as he hated copying other people’s work, an integral part of any art apprenticeship. Instead he moved to York, where he studied human anatomy and illustrated a book on midwifery. He continued to study anatomy and made money by painting portraits up to 1754 when he moved to Italy, then famous as a mecca for young artists. In 1756 he moved back to England and for two years lived in Lincolnshire where he studied the anatomy of the horse. He then moved to London where his talent was spotted by the Duke of Richmond who, in 1759, commissioned three paintings by him. He produced a classic book Anatomy Of The Horse in 1766.

George Stubbs’ paintings of animals, especially thoroughbred horses, are perfection

From then on he made a considerable income painting large canvases for wealthy clients such as Lords Grosvenor and Rockingham (for whom he painted as wonderful a portrait of a horse as any, Whistlejacket) and a large number of portraits of famous hunts and race horses and their jockeys. Certainly he was, and still is, the most celebrated artist in his field, with many classic masterpieces such as, The Grosvenor Hunt (1762) and Gimcrack on Newmarket Heath (1765), Stubbs died in 1806.

L. S. LOWRY

L.S. (Lawrence Stephen) Lowry was born at 1 Barrett Street, Stretford, Manchester on 1 November 1887 and later moved to Pendlebury, where he lived until he retired to The Elms, Mottram in 1948. After leaving school he trained at Manchester Municipal Art College and then went to Salford School of Art. Today people imagine that he was a full time artist, but he was not. For many years he was employed by the Pall Mall Property Company as a cashier and rent collector, but he kept this part of his life secret, and his employers seem to have been quite generous in giving him time off when his art conflicted with his work for them.

Lowry was a bachelor and led a rather shy, introverted quiet life. One problem that he had was his mother. His father died in 1932 and his mother, who seemed more or less bed-ridden, relied on him to look after her. So for many years he could paint for only a few hours when he was at home, when his mother had gone to sleep. She died when he was 51 years old in 1939 and this gave him the freedom to paint far more than he had done previously. Yet already his talent had been spotted. In 1943 he was made a professional war artist, and he was an official artist at the coronation of Queen Elizabeth in 1953.

Of course Lowry is best known for his industrial scenes from Lancashire, of cotton-mills, cobbled streets, football grounds (he was a fan of Manchester City FC) and row upon row of terraced cottages. And of his ‘matchstick men, cats and dogs’. At first critics were severe, calling these paintings naive and pointing out that the perspective in his paintings was often wrong. It was amateurish, said some, and smacked of a holiday and weekend artist rather than a serious painter. If only these critics were here today, to witness Lowry-esque paintings selling for umpteen million pounds! But Lowry was a far more versatile artist, and the Salford Quays art gallery, which houses the largest collection of Lowry’s work, shows his surprising versatility. Artists like Lowry invariably get showered with honours as they grow old, but in this Lowry holds a record. He is the only person to turn down the offer of an OBE twice, a CBE and a knighthood! Which suggests a curious attitude to life, perhaps.

He was a bit of a recluse, yet he was helpful to all young artists who sought his advice; he even bought lots of their work to encourage them. As his fame grew, so people wanted to meet him and some even dared to knock on his front door. To avoid them, he pointed to a suitcase and said that he was going away in a moment so he couldn’t spend time talking to them. Once, so the story goes, a great anonymous admirer called his bluff. He gave Lowry a lift to the railway station and watched him get on the train. Lowry got off at the next station and quietly returned home! Lowry enjoyed the paintings of other artists, especially Rossetti, and when his income grew as his paintings were ever more in demand, he spent much of his income on their work.

Lowry died of pneumonia on 23 February 1976 and is buried at Chorlton-cum-Hardy. A bronze statue of him was erected at Mottram. But go to Salford Quays to celebrate the man and his work.

JONATHAN LATIMER

Jonathan Latimer was born on 25 October 1976 at Billinge and is currently one of the world’s leading wildlife artists. He trained at Blackpool & the Fylde College where he graduated with a First Class Honours degree in natural history illustration. He won the Mary Elizabeth Barrow Award for excellence in art and design. After leaving college, Jonathan won the National Exhibition of Wildlife Art (2000). It is pleasing that the county still generates great people who are outstanding at ‘doing things’!

Coppull artist and book illustrator Jonathan Latimer won Birdwatch Artist of the Year (2003) with a large painting of a female hen harrier flying across a Welsh hillside in superb lighting

Five Inventors

Imagine that you are going to weave some cloth. Stand at the end of the loom and fix in place the threads that run the length of the loom, away from you. They are the warp threads. As weaver, your job involves feeding the threads that go across, the weft, alternately from right to left, then from left to right, between the warps. Your job also includes moving every other warp thread up or down between every pass of the weft and then to tamp down the weft to create the tight mesh that is cloth. It sounds complicated, and so the creation of a loom that would do this quickly and economically was one of the greatest of all inventions.

However, before you can weave, you must have threads for the warp and weft. Originally, when wool was the main clothmaking material, the spinning wheel was used. Loose wool was spun, a handful at a time, to produce a single strand of woollen yarn (the sort used in knitting today). The problem, when the population of Britain started to grow rapidly from the middle of the 18th century, was that this method could not provide the huge quantities of yarn to satisfy the weavers’ demands that would meet the growing need for cloth and clothing. Lancashire was the epicentre of the invention of machines that could produce the yarn and then weave the cloth.

JAMES HARGREAVES

James Hargreaves was born in 1720 at Stanhill, between Blackburn and Oswaldtwistle. In 1764 he invented a simple machine, called the jenny, that had eight spindles and could produce at least eight times as much thread as a spinning wheel. He then moved to Lower Ramsclough where he set up a workshop in a barn. There he improved his design but, with home-spinners feeling threatened by industrialisation and the building of big factories, he suffered from break-ins and the wrecking of his new machines. So he left Lancashire, moved to Nottingham and, in 1770, he patented a spinning jenny that could spin sixteen threads simultaneously. Hargreaves later moved back to Lancashire and died in Oswaldtwistle in 1778. His spinning jenny was soon overtaken by larger, even more efficient, spinning machines. By 1811 only about 3% of over five million spinning spindles in Lancashire were still jennies, all of them in small workshops and not factories. Besides efficiency, there was a problem with the thread produced by the jenny; it tended to be rough and weak, and suitable only for weft. This was no great problem, for by an Act of Parliament of 1721 it was illegal to make cloth from 100% cotton and other stronger threads (such as wool) would be used as warp.

SIR RICHARD ARKWRIGHT

Richard Arkwright was born in 1732 in Preston, and spent a short time in the 1750s living in Bolton, where he worked as a barber. There he invented a range of permanent dyes for the then-popular wigs and later for the dyeing of the cloth. He returned to Preston and then moved to Nottingham. There, in 1769, he patented his spinning-frame (though it is clear that the design was ‘borrowed’ from Thomas Highs of Leigh). Arkwright’s spinning-frame spun with a better tension than the jenny, by using wooden and metal pegs instead of the hands and fingers of people. It thus produced thread that was excellent as warp.

However the 1721 Act was still in force, until Arkwright and other pioneers in the cotton cloth industry persuaded Parliament to repeal it in 1774. In 1771 Arkwright again moved, this time to Cromford, on the banks of the River Derwent in Derbyshire. There he built the first water-powered factory, and his spinning-frame became called the ‘water-frame’.

Hall i’th Wood, near Bolton, the birthplace of Samuel Crompton in 1753

Now that 100% cotton cloth could be made, more cotton was needed and that led to the slave plantations of the West Indies and southern United States. But when the raw cotton reached Lancashire (through the Ports of Lancaster and Liverpool) much had to be done before it was ready to be spun into thread. Seeds and other trash had to be weeded out and the cotton fibres had to be aligned. Arkwright looked to the problem of dealing with the increasingly huge volumes of raw cotton and, in 1775, patented his cylinder carding machine that would produce quickly, fine, filmy lengths of clean cotton ready for spinning on his waterframe.

Samuel Crompton, the inventor of the Spinning Mule

Whilst Arkwright continued to have his home in Derbyshire, he invested elsewhere, including his native county. He opened Birkacre Mill in the Yarrow valley near Chorley which, by 1774, employed over 600 workers. Though the mill is gone, some of the masonry used to power it can be seen in the river. Arkwright died on 3 August 1792. But even his water-frame was superseded by….

SAMUEL CROMPTON

Samuel Crompton was born in 1753 at Hall i’th Wood, off that part of Bolton’s ring road named after him, Crompton Way. The demand for light, inexpensive cotton textiles was increasing rapidly and the water-frame was not producing threads fast enough. So in 1779 Crompton came up with his spinning-mule, with which a single spinner, hand-driving, could handle up to 144 spindles.

With the increase of water-powered mills in the 1790s and then the advent of steam-powered mills from the 1830s, much larger mules could be used, so that one worker could be responsible for up to 1,200 spindles. This great advance provided enough thread to provide cloth for the rapid growth of the human population of, not only Great Britain, but the world. Crompton’s mule was never patented, and accordingly was adopted wherever cotton was spun into thread. Crompton died in Bolton in 1827.

JOHN KAY

John Kay was born in Ramsbottom, near Bury, in 1704 and it was he who revolutionised the weaving of the threads to make cloth by inventing his flying-shuttle. The weaver would fix the ends of the warps in place down the length of the loom. Then, instead of the weaver having to push the shuttle carrying the weft to and fro through the warps, Kay’s machine did the work. Warps were separated, the shuttle quickly shot through (it flew through), the warps separated, and the shuttle shot through again..and so on. By having the shuttle flying through, especially when steam power became the normal way of driving cotton mills, broader cloth could be produced and, with the process becoming automatic, one weaver could attend to several looms. Kay died in France in 1780.

One more pioneer needs mention, the chemist John Mercer. He was born in 1791 at Great Harwood and died in 1886 at his home Mercer Park, Clayton-le-Moors. Pure cotton cloth is very soft and wears out easily and Mercer came up with a method of making it much more durable by treating newly-woven cloth with caustic soda. This seems to tighten up the fine cotton fibres. It is likely that, without Mercer’s input, cotton would not have dominated clothing through the nineteenth and first half of the twentieth century before the advent of hard-wearing man-made textiles.

One Eccentric Steam Nutter

FRED DIBNAH

Fred Dibnah was the sort of person that has become rarer as the 20th century gave way to the 21st: an obsessed, eccentric nutter. And I am sure he would enjoy me describing him thus. He was born on 28 April 1938 in Bolton and grew up surrounded by mill chimneys, steam engines, canals and their barges, and rows of terraced streets. His parents both worked in bleach mills and he left school at 16 with some art training and the desire to ‘do his own thing’ rather than conform and be one of the thousands in t’ mill. The result was that he made his money by climbing things, demolishing things, and appearing on TV, usually with a steam engine close at hand.

He had a head for heights, which most of us do not. So when he was 17 years old he had no qualms about climbing the 262 foot mill chimney at Barrow Bridge, just outside the town, for a ten shillings wager (in 1996 he repaired that chimney which now has a preservation order). Thus it was only natural that he should become a steeplejack. He once spent six months removing the top half of a 270 foot mill chimney, one brick at a time, because the mill was still in use. Then he was given the job of repairing and gilding the weather vane on Bolton’s parish church. In 1978 it was noticed that sixteen stone pillars supporting the clock on top of Bolton’s town hall were badly corroded through years of acid rain and soot. He made new pillars, put them in place and gilded the top of the clock. It was then that he came to the attention of the BBC and interviewed for Look North-West’s news programme.

He also felled the tall chimneys of abandoned cotton mills throughout north-west England, the last at Royton in 2004. His technique was simple and involved no explosives. He chipped away at the base of the chimney on the side that he wanted the thing to fall, removing brick after brick and propping the chimney up in the gap with wooden pit-props. When he calculated that, if all the props were to go, the chimney would fall, he built a fire in the bottom of the chimney around the props. The fire was lit, and Dibnah would crouch by its side, watching. Then, as the masonry he had not removed began to crack and the chimney began to fall, he would sound an old car horn in salute of its demise.

Once he was televised felling a chimney in Rochdale. As he emerged from the smoke and dust, horn in hand, he turned to the camera, ‘Did yer like that?’ he asked, with a broad grin. A TV star was born.

He loved ancient machinery, especially those driven by steam. In 1980 he bought, for £2,300, a 1912 Aveling & Porter traction engine and lovingly made it as new, making the parts that needed replacing himself. The traction engine, together with his trusty partners, became an integral part of his final TV programmes.

In 1979 the BBC docmentary Fred Dibnah Steeplejack won a BAFTA for best documentary. This led to him appearing on adverts for Kelloggs cereals and Greenall Whitley bitter. But then Dibnah appeared, wearing his oily overalls and hallmark flat cap, in a host of series from 1998 including Fred Dibnah’s Industrial Age, his Magnificent Monuments, his Buildings of Britain, his Victorian Heroes (Brunel was his favourite), his Age of Steam, and his Made in Britain. The latter was made in 2003-4 (broadcast 2005)when he was suffering from the prostate cancer that killed him on 6 November 2004, and had him driving round Britain in the traction engine that had taken him over 20 years to restore. He also drove his traction engine to London in July 2004 to receive his MBE from the Queen.

Fred had a turbulent love-life, mainly because his obsession with steam came between him and two of his wives: Alison (to whom he was married 1967-85) and Susan (1987-96). He last wife Sheila (1998-2004) was with him to the end. So too were his sons Jack and Roger, who appeared with him on his traction engine in Fred Dibnah’s Made In Britain. And he had similarly eccentric pals Donald Paiton and Alf Molyneaux who chatted away with him as though the TV camera was nowhere in sight. In this age, when TV and newspapers are full of shallow, air-head celebrities, Fred Dibnah was a down-to-earth man and I, for one, still enjoy putting on a DVD for an evening with Fred and his pals. ‘Boys’ toys on a grand scale!’ was how Alf described steam engines. ‘She’s a bit on t’ lively side!’ was Fred’s description of trying a steam engine he had never driven before, and he turned to the camera, Rivets once held everything together, like.

Following his death the BBC broadcast A Tribute To Fred Dibnah and his home town commissioned a bronze sculpture of him by artist Jane Robbins, which was unveiled on 29 April 2008, the day after what would have been his seventieth birthday.

Men Who Built Holiday Resorts

The Lancashire coast is famous for resorts like Southport, Lytham St. Annes, Blackpool, Fleetwood and Morecambe. Of these, Morecambe is the odd one out, for it was not founded as a resort, but it evolved into a resort when the railway was taken through to the coastal village that was then called Poulton-le-Sands.

Southport was not even a name on a map in the 18th century. There was a village at the north-east corner of what is now Southport called North Meols, also called Churchtown. From there, to the south and west, to the tiny hamlet of Birkdale, was one vast expanse of sand dunes. At one point, where a small stream flowed into the sea – a stream grandly called the River Nile – there were a few fishermens’ shacks, that went under the name South Hawes.

In 1770 the Leeds and Liverpool canal reached the hamlet of Scarisbrick, about four miles inland of Churchtown. This coincided with the new craze of ‘taking the water’, or bathing in the sea. So people from the nearer towns of Lancashire, such as Wigan and St Helens, took a barge to Scarisbrick and then a carriage to the shore at Churchtown. The problem with that was the muddy shore at Churchtown. So they were then transported on a track through the dunes to South Hawes. In 1792 William Sutton, alias the Duke, decided that there was money to be made here. He built a shack of a hotel out of drift wood by the Nile and a year later built a proper hotel that he called South Port. That was the start of Southport as we know it, for throughout the 19th century the town was quickly built, with its characteristic straight, broad, sometimes tree-lined streets of mostly middle-class housing. As well as a place to visit, Southport became a major dormitory town, by train, in easy commuting distance of Liverpool and Manchester. The land on either side of the broad straight track through the dunes that led to the Nile and the Duke’s Hotel was purchased in about 1830 by investors, who built grand houses and hotels there. And the track itself became the famous Lord Street, after the Lord of the Manor from whom it was purchased.

As for ‘the Duke’, he ended up bankrupt in Lancaster jail. He is still remembered as a street name, Duke Street.

BLACKPOOL

Blackpool is still one of the most visited seaside resorts in the world, and certainly the most visited in the United Kingdom. As early as 1750 the group of fishermen’s cottages that stood just above the high water mark were attracting a few visitors. But then two men realised that there was money to be had and they laid the foundation of today’s Blackpool. The first was Ethart a-Whiteside who, in 1735, built a cottage specially for the use of visitors. It was probably something of a boarding-house, and not very grand. Twenty years later, in 1755 Mr Forshaw built the first hotel at Blackpool, its position being on the corner of what is now the promenade and Talbot Square.

LYTHAM

Lytham is an ancient town, well over a thousand years old. In 1850, when Blackpool had already grown into a major holiday resort, there was almost nothing other than sand dunes between the two towns. Lytham ended at the western end of the Green, and Squire’s Gate (the southern end of Blackpool) began four miles away. This empty land was owned by the Clifton family and, in 1870, Lady Clifton had a chapel of ease built midway between Lytham and Blackpool that was dedicated to St Anne. In 1873 the Lytham-Blackpool railway line was built along the back of the dunes and in 1872 a road was built through the dunes connecting the two towns. This became Clifton Drive.

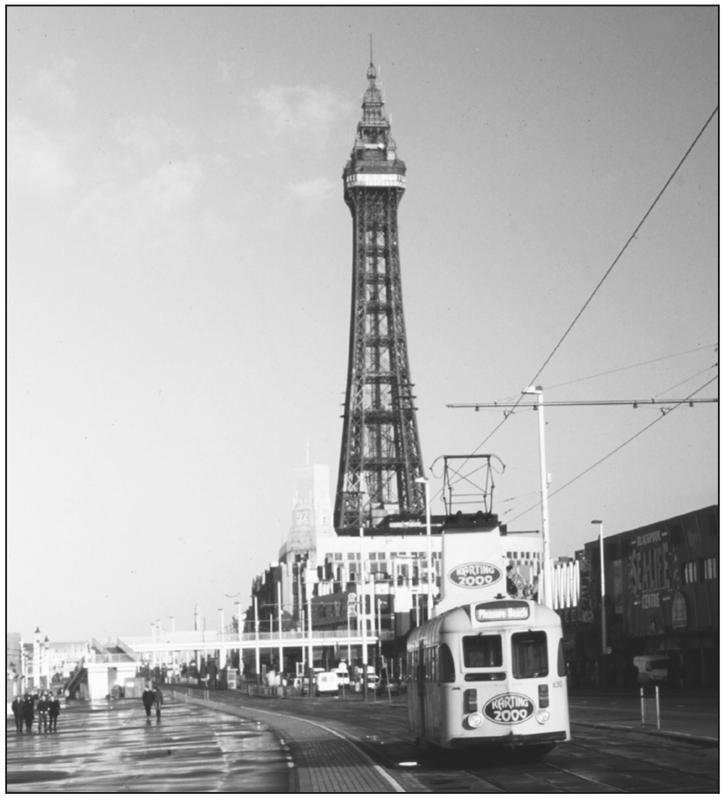

Blackpool Tower is a landmark visible from a large part of Lancashire. Its design was based on the Eiffel Tower in Paris

In 1862 Thomas Fair replaced his father James as the land agent for the Clifton family and it he who came up with the idea of flattening the dunes and building a modern holiday resort on the land. The Clifton family were unable to fund the work, but a Rossendale mill owner, Elijah Hargreaves, and seven associates, decided that an investment here would be very profitable. They formed The St Annes-on-the-Sea Land & Building Company on 14 October 1874, with a 999 year lease from the Clifton family. And in 1875 work commenced. Most of the buildings you can see in St Annes town centre around Clifton Drive and the promenade date from this time.

But there was still a gap in the development between St Annes and Lytham, that included Granny’s Bay, where local fishermen hauled up their boats. Here was constructed Fairhaven Lake (named after Thomas Fair), and some very grand houses. And to the north of Clifton Drive, further grand houses were built in an area called Ansdell, which took its name from the artist Richard Ansdell R.A., a friend of Thomas Fair.

FLEETWOOD

Rossall Hall, that is now a public school, was the northernmost building on the Fylde coast when Peter Hesketh was born there in 1801. When he was 23 years old he added another family name to his, becoming Peter Hesketh Fleetwood. At first he did very well for himself. In 1830 he became High Sheriff of Lancashire, and then from 1832 to 1847 was Member of Parliament for Preston. In 1835 he was influential in having a railway branch line put through to the mouth of the Wyre estuary, a couple of miles east of Rossall (it reached there in 1840), with the aim of building a new town there dedicated to holiday-makers and shipping.

To plan this, Hesketh Fleetwood turned to one of the leading architects of the day, Decimus Burton. Burton planned to have the highest sand dunes converted into a public park called The Mount, from which streets would radiate. These would be workers’ cottages. Then there would be a rather grand Queen’s Terrace and splendid North Euston Hotel overlooking the estuary. Finally, Burton planned two lighthouses, a small one and then a taller one called the Pharos, which were first lit in 1840, and a wharf for boats to tie up (opened in 1841).

But Hesketh Fleetwood did not have sufficient spare cash to fund the building of his town, Fleetwood. In 1841, to pay for the project, he began selling off his estates in the Fylde, and then in 1842 his estates around the new town of Southport. Finally in 1844 he sold Rossall Hall and moved out.

At first Fleetwood was a successful project, mainly because it had proved impossible to push the railway north through the fells between Lancaster and Penrith and so onto Scotland. People then took the train to Fleetwood, stayed in the North Euston Hotel and then took a ship to Ardrossan (Glasgow). In 1846 this was one of the journeys that travel agent Thomas Cook could arrange for you. And in 1847 Queen Victoria and Prince Albert arrived at Fleetwood from Scotland on their journey back to London. But then the railway was pushed through the Shap Fells, making the deviation via Fleetwood redundant. Later, of course, the town became a major fishing port as well as a sort of outlier of Blackpool, reached by tram.

How a Famous Word was Invented

Lancashire was the county and Preston the town where the temperance movement began in Britain. The instigator was Joseph Livesey who, in March 1832, encouraged people to come and ‘sign the pledge of abstinence.’ He held meetings to preach the virtue of total abstinence of the demon drink, he opened a temperance hotel in the town and he produced a magazine to further his drive.

That year, Richard ‘Dicky’ Turner, a fish salesman from Walton-le-Dale, had been drinking and was half sozzled. He saw a sign advertising one of Livesey’s meetings and went in deliberately to have a laugh at Livesey’s expense. But, like St Paul on the road to Damascus, he saw the light. He signed the pledge and gave up all alcohol. Now Dicky Turner suffered badly from stuttering, and it was at a temperance meeting where Dicky Turner told the audience: ‘Tha mun be reet out and out abhat it. T..t..t..t..,’ he stuttered, trying to get out the word ‘total’. ‘T..t..,’ he forced it out, ‘t’t’tee..tee..teetotal abstinence.’

And so a simple chap from Preston invented the word, ‘teetotal’.

A Great Hero

Wallace Hartley was born on 2 June 1878 in Colne in east Lancashire. At school he learned how to play the violin and, after leaving school, played in small bands and eventually, in 1909, joined an eight-man band that entertained guests on the Cunard RMS Mauretania. At the begining of April 1912 he became engaged to his sweetheart, Maria Robinson, and was promoted to bandleader. And so when White Star Line RMS Titanic set sail on her maiden voyage, Hartley was on board, ticket number 250654 in Second Class (even staff had tickets, free of course).

As we all know, on 15 April 1912, the unsinkable Titanic hit an iceberg and sank. To calm the passengers making for the lifeboats, Hartley insisted that the band carry on playing, and it is said (no good evidence exists) that as a finale they played Nearer My God To Thee. Another version has it that the band stopped playing just before the ship went down and stood on deck as one by one they were washed away. It has even been reported (though by whom, we do not know) that Wallace Hartley’s last words to his band were, ‘Gentlemen, I bid you farewell!’

His body was found floating in the Atlantic two weeks after the sinking. Forty thousand lined the streets of Colne and one thousand attended his funeral. He was a great hero.

Wallace Hartley who is said to have kept his band playing as the Titanic sank