The history of the United States can be told as an endless striving for better bread. Before fields of amber grains were sown on the continental United States, arriving colonists in Virginia and Massachusetts disembarked from their ships clutching chunks of hard brown bread. There was no wheat to be found, so the settlers planted stores of grains they’d brought with them. But their crops failed. When the settlers were starving, the indigenous people introduced them to corn, the ancient survival grain of Mesoamerica. The Europeans viewed maize as animal fodder; they thought it was revolting. But they started to cook with it, beginning with native fry cake, which they called hoe bread or hoecake.

In America, bread baking began at the open fire, became an industry, and is now the star of an artisanal movement.

Hoecake . . . Ash Cake . . . Journey Cake . . . Johnnycake . . . Corn Dodgers

The Indians munched corn on the cob, popped the kernels, used them to make mush and puddings, and pounded them into flour. They taught colonists to make a corn batter which, when cooked on a rock griddle or wooden board, became the flat bread known as johnnycake or journey cake for its rock-hard texture and inability to spoil. By the mid-eighteenth century, settlers cooked cornmeal hoecakes on paddles over open fires—and according to one Pennsylvania legend, on the blades of weeding hoes—and baked them in brick ovens cut into the mass of their walk-in fireplaces. The most rudimentary mixture of cornmeal, water, and a little pork fat made a bread called corn pone, corn dodgers, or skillet bread; this was a staple of slaves and poor rural white folks in the South. A loftier bread favored by the upper classes was made by adding eggs, buttermilk, salt, butter, and leavening such as baking powder or soda. In the North, more shortening plus sugar created “Yankee cornbread.” Today, cornbread tends to be crumbly yet moist. Cooks often change the texture by combining cornmeal with other flours and sometimes fresh corn kernels. Often savory seasonings such as chiles or herbs are added, as in Jamie Pagana’s Rich & Herby Cornbread (see next page). When baked in an oiled, preheated cast-iron skillet, cornbread develops a crisp, nutty crust that makes a lovely contrast to the moist interior.

CORN PONE OPINIONS

Jamie Pagana’s Rich & Herby Cornbread

The Apache Reaper, Edward Curtis, c. 1906.

Amber Waves of Grain

In 1830, producing 100 bushels of wheat required about 250 to 300 labor hours by hand, using broadcast sowing, a walking plow, scythes to cut, and flails to thresh kernels from the chaff. Sixty years later, after the patent of the McCormick reaper and the introduction of John Deere’s steel plow, practical threshing machines, horse-drawn straddle-row cultivators, and grain elevators and silos, 100 bushels of wheat could be produced in forty to fifty labor hours. This increase in efficiency coincided with the mass immigration of Mennonites fleeing mandatory Russian military service; members of the same religious sect fleeing Prussia had turned Russia into the breadbasket of the world. They brought their knowledge of farming and their trunks full of hearty Turkey Red wheat—first developed in the Fertile Crescent—to Nebraska, Kansas, the Dakotas, and the central Canadian plains, and planted an American wheat revolution.

Traditionally grain had been stone-ground, but during the Industrial Revolution a process was developed to roller-mill wheat, crushing the germ (but removing the nutrients and flavor) and extending its shelf life past one day, thus making “refined” white flour—once used only by the wealthy—affordable to the larger population. Today, as an emphasis on whole grains returns, small stone grinders are being revived and large food producers such as ConAgra are installing gigantic stone mills.

In 1909, the Alsop Process Company of St. Louis filed a patent for a process that used chlorine to bleach flour.

Naturally present wild yeast has been used to leaven bread and make ale since at least 5000 B.C.—but the yeast cells that would make commercial yeast possible weren’t isolated until the middle of the nineteenth century. Before then, bakers made their own leaveners from ingredients such as hops and the water left from boiling or soaking potatoes, then saved a portion of each bread batch as a starter for the next one.

Wagon trains setting off from Independence, Missouri, on the Oregon Trail expected to cross the country in six months. Some families walked a cow or two and perhaps had some hens tucked into the wagon, but bread was their mainstay. Guides suggested packing 200 pounds of flour and half a bushel of cornmeal for each adult. To transport their starter most efficiently, some women soaked bedsheets in it, dried, folded, and packed the sheets, then reconstituted the starter on the trail by moistening the sheets with water. Pioneers often pampered bread starter in the warmest part of the wagon, and when winter weather came, took the precious substance into their beds. The “overlanders” baked bread in folding tin reflector ovens or heavy cast-iron Dutch ovens with three legs and a lid over fires of scrounged fuel—from buffalo chips to dried weeds. For quick bread, they mixed dough in empty flour sacks, inserted a long stick, and, compacting the dough around it, stuck the “bread pop” in the ground beside the campfire to roast.

Thirty-three horse team harvester, cutting,

threshing, and sacking wheat, 1908.

Because biological yeast was unreliable, most bakers supplemented their sourdough starter with saleratus, an alkali bicarbonate of soda that replaced the colonial-era pearl ash or potash (potassium carbonate) derived from leaching wood or plant ashes. By 1850, baking powder—combining sodium bicarbonate with cream of tartar—replaced saleratus, making a greater range of baked goods, such as scones, biscuits, and fruit and nut breads, all quick and easy to prepare.

The introduction of baking powder brought about a sea change in cake and bread making. Spurred on by the new quick-rising formula, layer cakes, sponges, Swiss rolls, and soda bread were developed. Baking powder, moisture, and heat, when combined, liberate carbon dioxide gas to raise the dough or batter.

In 1876 Charles and Maximilian Fleischmann introduced commercially produced yeast at the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition, luring many of the 10 million visitors to their Viennese bread concession by circulating the scent of baking bread through the exhibition hall.

Before the invention of chemical leavening agents such as baking soda and baking powder, bakers who wanted air in their bread and didn’t have the time for yeast rising beat the daylights out of stiff dough. The dough was leavened by the continual folding of air between its layers, administered by thwacking it with a skillet or mallet—or, as legend has it, a granny with her musket. Beaten biscuits, made of flour, milk, and lard and pricked on top with a fork before baking, were the pride of the South. They are the rich, dense cousins of crackers.

FROM OPEN FIRE TO CLOSED STOVE

Because of the hard work required to produce it, the beaten biscuit soon became a status symbol, a chore for the plantation cook. Recipes called for using a tree stump as a work surface, and giving 200 wallops with a flat ax blade for everyday biscuits, and 500 to make them smooth enough for company. In the late nineteenth century, a Missouri manufacturer produced the biscuit brake, a worktable with a hand-cranked double roller like a toothed washing wringer that eased the burden of biscuit beating. With the invention of baking powder and the marketing of commercial yeast, the labor-intensive biscuits fell out of favor—though the memory of their distinctive flavor and texture persists. Linton Hopkins, the chef-owner of Restaurant Eugene in Atlanta, developed a food processor method for beaten biscuits that satisfies the urge for the heavy, old-fashioned bread.

It’s a Wrap: The Best Thing After Sliced Bread

Bread slicer, St. Louis, 1930

Bread wrappers offer a double bonus: the baker can advertise on the wrapper, and bread wrapped by machine is handled less by bakery employees. The first wrapping machine appeared in 1911; it used a wax seal to close the ends of the paper. Three years later, a new machine folded waxed paper around the loaf and sealed it by means of a heating plate. This process was not perfected until 1930, but because the cost of the new equipment raised the price of bread, many bakers did not install bread wrappers until the Depression ended.

The automated bread slicer was invented by Otto Frederick Rohwedder of Davenport, Iowa, in 1912. It was first used commercially by the Chillicothe Baking Company in Missouri, whose Kleen Maid Sliced Bread was released on July 7, 1928. The bread was advertised as “the greatest forward step in the baking industry since bread was wrapped.”

Sliced bread may be one of civilization’s greatest achievements, but it goes stale much faster than uncut loaves, and bakers were slow to offer it. Wrapping machines were improved, and later, preservatives were added to keep bread fresh.

Great Depression bread lines, New York City.

By the early twentieth century, only one in four households still baked bread at home. The number continued to slide by 1930, when Wonder Bread marketed sliced bread nationwide.

Wonder Bread defines factory bread. This originally unsliced bread was first baked by the Taggart Baking Company of Indianapolis around 1920. Taggart was acquired by Continental Baking Company in 1925, which sold sliced Wonder Bread in 1930 and promoted it extensively throughout the decade. Wonder Bread was produced at a full-scale bakery at the New York World’s Fair in 1939–40 and was the sponsor of popular radio programs. During the 1940s, the federal government became concerned with the nutritional deficiency of white bread and temporarily mandated that it be “enriched” with B vitamins, iron, folate, and calcium to curb pellagra and beriberi. Continental also found a way to create a loaf so soft that it could be squeezed into a fist-sized ball, and “enriched” Wonder Bread was advertised on children’s radio and television programs such as Hopalong Cassidy and Howdy Doody beginning in 1941. In the 1950s, the company introduced the slogan “Wonder Bread Builds Strong Bodies 8 Ways” for the product. During a backlash against overly refined foods in the 1960s, Wonder Bread became a prime target for criticism.

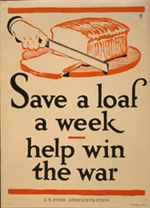

In an effort to fight wartime shortages, the sale of sliced bread was banned briefly in 1943.

Learning to make good bread, Bethune-Cookman College (GORDON PARKS, 1943).

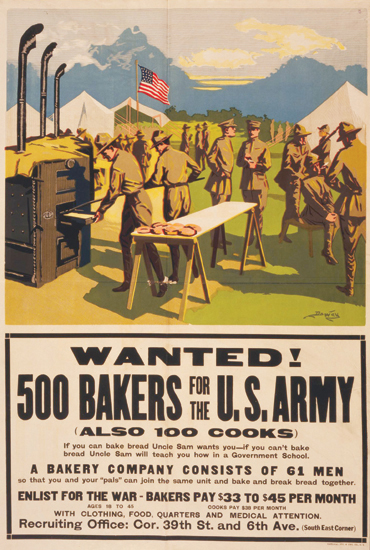

Marine Corps, USN School of Baking c. 1917.

Sylvester Graham and Whole-Grain Bread

Years of flattened lunch box sandwiches helped fuel a small market backlash against the whitest of all white breads. By the 1950s, many consumers longed for a more authentic packaged bread, a niche soon filled by Pepperidge Farm, a company started by Margaret Rudkin, a Connecticut housewife. When Mrs. Rudkin, who wanted chemical-free bread for her allergic son, used quality ingredients to produce thinly sliced bread, the desire for tea sandwich elegance and the trend toward dieting were joined.

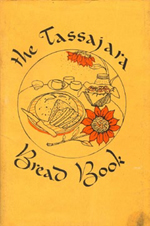

Bread emerged from the dark ages of bleaches, bromides, and hydrogenated fats just as approximately 1 million young people established counterculture homesteads in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Espousing the “simple life” of self-sufficiency—vegetable gardens, farm-raised meats, foraged greens, wood heat, and bread made of unprocessed whole-grain flour—“whole earth” proponents who had been raised on fluffy white bread formed co-ops and bought oats, millet, amaranth, wheat bran, brown rice, and seeds. They baked dense, barely edible New Age loaves. But once they learned to bake healthy bread, they longed for tasty bread.

To this yearning mass came the Tassajara Bread Book by Edward Espe Brown, head cook for a California Zen meditation retreat. An unpretentious paperback with a gentle philosophy and clear instructions and line drawings for the neophyte, it inspired the counterculture to fire up the wood stove, suburbanites to preheat the electric ovens, and everyone to roll up their sleeves and knead dough. People who had barely heard of whole-grain bread became baking fanatics. By the mid-1970s, homemade bread was once again the staff of life for many.

Suzanne Lupin, a farmer, baker, and

cheese maker in Vermont removes bread

from the wood-fired oven that she built.

Some home bread bakers cherish the sourdough starter they’ve had since the 1970s; they swear by their favorite bread flour; they scour their houses and apartments for a spot near a radiator—or air conditioner—to rise or retard a sponge; they find kneading dough, coaxing the rough mass into elastic life, close to spiritual; they mist the oven with a plant sprayer, or drop ice cubes into a hot pan to make steam for a crusty baguette. They are passionate, ecstatic, gaga about bread baking. Some build elaborate outdoor ovens, as normal people have done for centuries.

Many cooks, unable to buy good bread, bake bread of necessity. But they resent the sweat and mess of kneading and the time it takes to proof dough. They do not want to devote an entire day to baking. They want tasty bread, made with prime ingredients and little fuss.

In 1894, African American inventor, cook, and restaurateur Joseph Lee of Boston patented his dough-kneading machine; almost a century later, the bread machine, a Japanese-made refinement, caught on in America. Fully automated to add ingredients at the proper time, mix and knead the dough, and proof, raise, and bake the loaves, it rejuvenated home baking for many cooks.

Other time-stressed home bakers pounced on the recipe for no-knead bread originally developed by Jim Lahey of Manhattan’s Sullivan Street Bakery that food writer Mark Bittman shared in The New York Times in 2006. Bakers who tried the recipe filled blogs and chat rooms with their comments. The bread’s authentic rustic look, full-bodied taste, and easy preparation triggered another mini revolution.

America adores toast, the alchemy of bread dry-heated until its surface caramelizes into a sweet, crunchy gold crust. Throughout history, toast has had one major problem: it burns—easily. And the search to develop a gizmo that would produce perfectly browned toast indoors, without the aid of a flame or hearthstone, gripped the imagination of many an engineer and tinkerer.

The invention of the electric toaster is credited to Albert Marsh, who in 1905 patented a nickel and chromium alloy that could be shaped into an element capable of heating bread to 310°F without burning down the house. The first electric toasters were a marvel of exposed coiled wires on a ceramic base. From then on they became objects of beauty and ingenuity: some could flip toast, some carried toast in metal baskets, one used a conveyor belt to move the toast. But none could automatically prevent burning.

In 1926, Charles P. Strite patented his pop-up toaster, the Toastmaster. A few years later, along came sliced bread, making the toasting process a snap, and the perfect marriage was born. Innovations continued: wide slots accommodating bagel halves, toaster ovens, sleek and stylish toasters, glass toasters, even Pop Art toasters that burn designs onto bread.

The Wrong Way to Disconnect a Toaster (ANN ROSENER, 1942).