Cooking alone in the kitchen has the delicious feeling of a stolen moment, and there are evenings when a quiet, cozy table for one is an unsurpassed luxury. But the charm of solitary meals is mostly considered un-American. Cooking and eating in the United States have long been social activities. Beginning in our early history, building and tending the fire as well as gathering and preparing the food with the rough tools that were available required a group effort. Maybe the sense of hard-won accomplishment made food taste better, or perhaps the numbers of people gathered at the table created warmth, well-being, and excitement and turned meals into feasts. At church suppers and firehouse dinners, the regional community feeds and festivals, we regularly sense being part of something greater than ourselves, or at least something greater than a TV dinner.

In-ground cooking made a giant leap forward after the Europeans introduced iron pots to the new world. Emblematic in-ground meals—the New England clam bake, lobster bake, beanhole beans and hasty pudding; pit-barbecued pig in the Southeast; lamb in the Midwest, beef in the Far West; and luaus in Hawaii—seemed to spring from the soil of different regions.

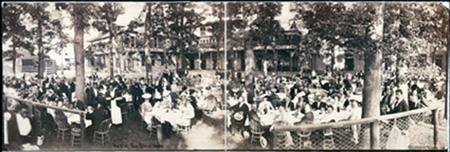

Orchard Beach, Maine, Clambake c. 1861–80.

Allen’s Neck Clam Bake

Washington State Oyster toast.

The Wampanoag Indians—“people of the first light”—who greeted the Massachusetts Pilgrims, had a long tradition of giving an appanaug, or clambake, to honor tribal events and seasonal changes. But the colonists reviled clams, eating them only as starvation rations and using them to fatten pigs. By the late nineteenth century, mass transportation had turned clambakes into a tourist opportunity.

The annual Allen’s Neck Clam Bake, perhaps the most fabled and authentic community clambake, began in 1887 as a gathering of the Quakers living in the Westport, Massachusetts, area. The Friends now host over 500 paying guests lucky enough to get a ticket. They line their two-foot-deep Allen’s Neck pit with a ton and a half of cannonball-sized rocks, and count on a truckload of seaweed and a cord of four-foot, split wood to cook over 20 bushels of clams, 200 pounds of sausage, 75 pounds of fish, 150 pounds of tripe, and 75 dozen ears of corn—a celebration of community, cooperation, and historically good eating.

HOW TO PREPARE THE IDEAL NEW ENGLAND CLAMBAKE, NO MATTER WHERE YOU LIVE

Arrange for fair weather.

Find yourself a legal beach, yard, or maybe a vacant lot where you won’t set the trees on fire.

Shovel out a pit; line it with big, round rocks.

Build a rousing wood fire that will burn for a couple of hours while you tie up steamers, quahogs, and mussels into cheesecloth bundles.

When the rocks glow hot, let the fire burn out.

Rake the searing coals between the rocks.

Strew the pit with sopping wet seaweed and listen to it pop and crackle.

Quickly place the shellfish packets onto the seaweed.

Pile on glorious lobsters, don’t skimp, get plenty.

Between blankets of dripping seaweed, layer sweet corn, new potatoes, and onions.

If you like, add salted, peppered chicken parts, and firm linguica or chorizo sausage.

A final layer of soggy seaweed and you’re set.

Cover the great pile with a canvas tarp or lots of gunnysacks.

Wet them down nicely so they won’t burn up.

Seal the cover edge with stones for in-ground steaming.

Assemble your good and hungry group.

Open a beer, pop a bottle of champagne, or pour some iced tea.

Prepare to chat or play ball with the kids for a couple of hours.

At long last, swoop off the canvas cover and remove the clambake.

Arrange on great platters, or dole a little of everything onto plates.

Serve with melted butter and lemon slices.

Maynard Stanley’s Beanhole Beans

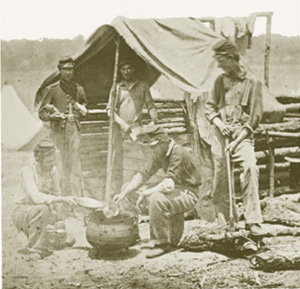

Before barbecue acquired little wheels and began strutting its stuff around the patio, the barbecue pit was a hole in the ground, and barbecue involved an entire animal. Going to a barbecue was a daylong event for dozens, if not hundreds, of people.

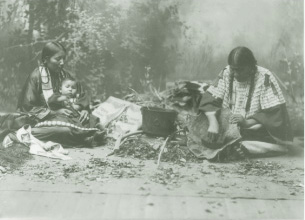

When a Navajo girl reaches puberty, her family may conduct a kinaaldá for her; this is a traditional five-day, four-night ceremony to prepare her for womanhood. The girls run three times a day, and in between, they are groomed, bejeweled, and enrobed in special outfits whose colors reflect the four sacred directions. Her hair is bound, then washed in yucca root. She is molded in the image of Changing Woman, one of the most important deities in Navajo culture. She participates in an all-night sing (or blessing ritual) conducted by a medicine man—and through it all prepares a 100-pound corn cake that will be baked directly in the earth and distributed to all guests at the end of the ceremony.

On the first day, the men in the family dig the hole in which the cake will be baked. Too shallow, and the batter will overflow it; too deep, and the cake won’t cook through; too crooked, and the cake won’t bake evenly. Once the hole is perfectly shaped—about the width of a standard garden shovel and about 8 inches deep—the men cut dry piñon and juniper and haul it to the pit. There has to be enough to keep the fire burning for three days and nights.

Over the next three days, they spread 100 pounds of dry white corn on a tarp and check each kernel by hand. The corn is then roasted and ground, some by hand with a traditional grinding stone. After the women sift the cornmeal three times, through progressively finer screens, the strenuous work of mixing 100 pounds of meal with boiling water begins. Mixing the batter is both celebration and endurance test. When an elder declares the batter ready, the action moves back outdoors.

The family removes wood and ashes from the pit and lays wet paper bags on the bottom, topped with a specially constructed corn husk cross. They pour in the batter, bless it, top with another corn husk cross and more wet paper bags, then rebury it with sand, hot ashes, and more wood. They relight the fire and watch all night as the cake steams in the hot earth. On the fifth morning, after the kinaaldá’s last predawn run, the family uncovers the cake as ceremoniously as they put it in the ground. The young woman cuts small pieces and offers them to the elder supervising the baking and the medicine man. If they agree it’s perfect—moist, sweet, the adobe color of the earth in which it was baked—legend says the young woman will have a good life—and more important, always have enough food to share with her family and the tribe.

Ruth Kendrick’s Winning Dutch Oven Salmon in Black and White

Iron pots set above the fire gave birth to regional specialties that, like in-ground meals, showcase local ingredients, are an ode to the cultural history of a place. Chowder still means New England, Kentucky is burgoo, and the low country is Frogmore stew. If the church supper is jambalaya or a crawfish or shrimp boil, you know you are in Louisiana. Cioppino still smacks of San Francisco, and chili—well, you need to taste it before you can use that dish as a GPS.

Wayne Calk’s Gold Star Chuckwagon Chili

Leah Chase’s Famous Gumbo des Herbes

Helen Griffin Williams’ Macaroni and Cheese

INVENTING TRADITION: GREEN BEAN CASSEROLE