Ice cream is an inalienable American right, as close as we come to one single, undivided national appetite. The initial shock of ice cream against the tip of the tongue is a mark of American childhood. In the eighteenth century, the dessert was a rare and labor-intensive luxury. But time and technology eventually delivered the “frozen dainty” to Main Street. Indeed, ice cream was the first taste of America offered to immigrants at Ellis Island. Americans each consume an average of 22½ quarts of ice cream a year.

Thomas Jefferson’s Vanilla Ice Cream

From France to Philly–Via the White House

In the nineteenth century, Philadelphia, with its public ice cream gardens, was the center of the ice-cream universe, and many accounts say that Augustus Jackson, an African-American candy maker who had worked as a chef in the White House, was the emperor of Philadelphia ice cream. Making the confection was still an arduous task. Large blocks of ice were harvested from rivers in the winter and stored in straw for the summer treat. An 1894 article in the New York Times claimed that Mr. Jackson invented a method for beating more air into the frozen egg and cream custards. The results were so toothsome that his ice cream fetched $1 a quart and, said the Times, “It immediately became popular, and the inventor soon enlarged his store, and when he died left a considerable fortune. A good many tried to follow his example, and ice cream was hawked about the streets, being wheeled along very much as the hokey-pokey carts are now, but none of them succeeded in obtaining the flavor that Jackson had in his product.”

Other accounts maintain that Mr. Jackson wholesaled his ice cream to the city’s ice-cream gardens, many of which were owned by African Americans. During Mr. Jackson’s reign, “French style vanilla ice cream” was rechristened and became “Philadelphia style vanilla ice cream.”

President Roosevelt’s secretary accepts an ice cream cake from the International Association of Ice Cream Manufacturers.

Before she married James Madison, Dolley Payne Todd served as the hostess for many of Thomas Jefferson’s gatherings at the White House and became as famous for her lavish fêtes as she did for her elaborately molded ice creams. The pink tower of strawberry ice cream that she served on a silver platter at her husband’s second inaugural ball in 1812 captured the public imagination and ice cream became de rigueur at fashionable parties. In one account Augustus Jackson prepared the pink tower using cream from Madison’s dairy in Montpelier and strawberries from Dolley’s garden at the White House.

Strawberry Buttermilk Sherbet

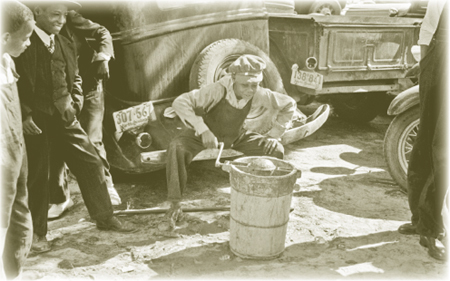

Children making ice cream for a church benefit.

Technology

The cost of ice and the labor required to freeze cream flawlessly ensured that only the wealthy could indulge in the stuff. It took three servants to freeze the cream—two turned the freezing canister in its ice bath and another scraped the cream from the sides of the canister as it froze.

“It is the practice with some indolent cooks, to set the freezer, containing the cream, in a tub with ice and salt, and put it in the ice-house; it will certainly freeze there, but not until the watery particles have subsided, and by the separation destroyed the cream,” wrote Mary Randolph in The Virginia Housewife. But in the early 1840s, Nancy M. Johnson mounted a one-woman revolution in ice cream. She attached a crank and a handle to the side of a metal canister, placed the canister in a wooden bucket of ice, and turned icing cream into a one-person job.

Opinion is divided as to where this bit of practical magic occurred—New Jersey, Washington, D.C., or Philadelphia. Lacking the funds to manufacture her invention, Mrs. Johnson sold her patent two years later. Some say it fetched $200, others $2,000, but there is no disputing that the device patented in 1843 is still in use today. It was also built to giant scale to be powered by horses, and turned ice cream from a homemade treat into a manufacturing industry.

Today American consumers spend $8.1 billion a year on home purchases of ice cream, but $13.3 billion on ice cream eaten away from home—at restaurants diners, snack bars, ice cream stands, the ballpark, and the beach.

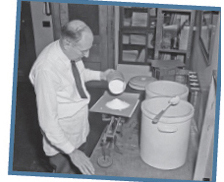

Owen E. Williams, who discovered how to preserve sweet cream indefinitely with sodium chloride, HARRIS & EWING, 1939.

Early Prohibitionists were concerned by how easily soda water could conceal the addition of booze and by its similarity to champagne. By the 1880s a number of municipalities had banned the sale of the suspicious substance on Sunday. This wreaked havoc on the ice cream soda business. Some enterprising soda fountain owner hit on the idea of offering a soda-free ice cream soda—ice cream with chocolate sauce and whipped cream—on Sunday. The first ice cream Sunday may have been served in Evanston, Illinois, in 1890, or the next year in Two Rivers, Wisconsin, or in 1893 at Platt & Cole’s drugstore in Ithaca, New York. Most likely, gilding the ice cream lily was a food concept with multiple points of entry—another example of how good things get better (or at least bigger and richer) in the United States. George Giffy, a soda fountain owner in Manitowoc, Wisconsin, changed the name to the ice cream sundae.

Janet Cheechuck’s Hot Fudge Sauce

“You, icy sweetness of strawberry, chocolate or vanilla, melting, stickily into your inverted dunce cap, ravisher of appetites, leading the younger generation from the straight and narrow paths of spinach, pilferer of the pennies that might go to make a fortune; destroyer of the peace of homes, instrument of bribery and reward of virtue.”

—H. L. Mencken, Baltimore Evening Sun, 1928

We All Scream

Nearly every Great American Ice Cream Empire sprang from a small ice cream shop, pushcart, or truck. Sold in England prior to 1904, the edible, grab-gobble-and-go cone was introduced to Americans at the St. Louis World’s Fair that year. Historians believe that more than fifty vendors sold ice cream cones at the fair.

1920 Prohibition reduced legal alcohol consumption and raised the amount of ice cream eaten in the country by 100 million gallons. Harry Burt, who owned an ice cream store in Youngstown, Ohio, invented the Good Humor Ice Cream Sucker with its chocolate coating, and wooden stick. The motorized trucks made him the first nationwide ice cream baron.

1925 When Howard Deering Johnson found that the soda fountain was the most profitable section of his drugstore, he offered three flavors—vanilla, chocolate, and strawberry—using his mother’s ice cream recipe, which was higher in butterfat than most. By 1950, Howard Johnson’s offered 28 flavors and had 400 locations across the country.

AUGUST 4, 1938 John Fremont “Grandpa” McCullough and his son, Alex McCullough, talked their friend Herb Noble into selling all-you-can-eat bowls of their invention—soft-serve ice cream—at his ice-cream store. Two years later, the three men opened the first Dairy Queen in Joliet, Illinois. The first food business to offer independent franchises, the company has 5,900 stores around the world today.

1953 Burt Baskin and Irvine Robbins opened an ice cream parlor in Glendale, California. At the suggestion of their Madison Avenue advertising agency, the partners offered 31 flavors—a new flavor for each day of the month and more flavors than Howard Johnson’s—with the slogan “Count the Flavors. Where Flavor Counts.” Today there are 5,800 Baskin-Robbins outlets around the world.

1960 Reuben Mattus founded Häagen-Dazs, a high-butterfat ice cream made with all natural ingredients. The nonsensical name was meant to evoke old world quality, but the ice cream was made at a small factory in the Bronx and shipped via Greyhound buses to college students across the country. Mattus and his widowed mother had immigrated to the United States in the early 1920s and sold frozen ices from a horse-drawn cart in the Bronx. In 1983 the company was sold to General Mills for $70 million.

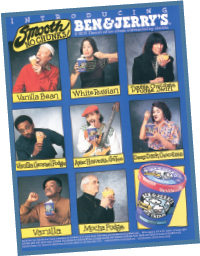

1978 After completing a correspondence course in ice cream making, Ben Cohen and Jerry Greenfield, opened an ice cream parlor in a former gas station in Burlington, Vermont. Like Häagen-Daz, Ben & Jerry’s ice cream was high butterfat, but instead of old world tradition, the owners created tie-died improvisations such as Chubby Hubby and Rain Forest Crunch by mixing candy and even cookie dough into the ice cream and then marketed the flavors with a leftie social conscience. To sell their ice cream they used campaigns such as an annual free cone day and drove a truck painted like a cow—the cow mobile—across the country. They got it placed on the space shuttle and used it to build the world’s largest baked Alaska in Washington to protest global warming. Through their foundation they pushed corporate giving and good works to new levels. In 2000 the company was acquired by Unilever for $326 million.

Adria Shimada’s Raspberry Sorbet

People’s Pops: Peach, Chamomile, and Honey Pops