Someone was knocking on the door and there was a buzzing in my head. The light in the room was different. I’d fallen asleep and my phone was vibrating under the pillow.

‘What?’ I said, heavy and disoriented. Dry throat, bitter tongue. I hoped it was Dad but Sam coiled his way in and closed the door with his back. He was holding the cat. I pulled myself up to sit against the headboard and reached under my pillow. Along with my phone I pulled out something else – Dad’s old compass. What was that doing there? I hid it again quickly.

There was a missed call from Essie and one from a new number. I felt my heart decide that it was Evan’s.

Sam sat down on my bed, rubbing Scribble under the chin. I fidgeted. Me and cats didn’t get along. I couldn’t stand Scribble. That was a big deal for some people – a few of the girls at school would actually cry if I ever told them but all I had to go on was a cat that saw me as nothing more than a human scratching post. We kept out of each other’s way. Of course, he loved my brother.

‘You okay?’ said Sam. He sounded sombre and patronising, but I didn’t want a fight. I remembered him wrecking our Christmas tree.

‘Not really.’

The weight of him on my bed made me bristle. Why did he have to fill every space he was in? He’d made Dad feel small these last two years, and had loved it.

‘So, you really didn’t know,’ he said.

‘That Dad was leaving? I had no idea, you idiot. Why would you even think that? And where’s he gone?’

‘I don’t know and I don’t care. Nor should you. We’ve got to look after Mum. She’s taken it really bad, Han.’

My phone chimed a voicemail message, which made me tense up even more. ‘I can see that, thanks.’

‘Don’t be immature.’

‘Me? You’re the one who ran off today instead of helping me with Essie.’ That was the wrong thing to mention.

‘Help you what? You took one look at the old bat and started organising her bloody funeral.’

‘Shut up. She did look dead. Really dead – you didn’t see her.’

‘No, no one but you did.’ He smirked. I wanted to thump him so badly. ‘Anyway I didn’t run off – I went to get Mum, which was the right thing to do.’

He could smell my weakness. I wished I could have faith in the things I’d said and done.

Sam let go of the cat and I watched as Scribble curled up on the end of my bed. Well, that was new.

‘And about that,’ he said, ‘you’ve got to start seeing Essie for what she really is. She’s evil, Hannah. You can’t trust her. She’s messed up.’

‘She is not! She told me everything – there was an explanation for what happened this morning, if you’d bothered to stick around.’

‘That’s bull. She’s always having us on about something. What about when she said the cleaning woman was stealing things?’

‘Maybe she was!’

‘Hannah, seriously. Do you even remember the time she made Mum lose her job?’

I didn’t, and I didn’t think Sam did either. We were little kids then. We only knew about it because Mum and Dad always talked about things Essie had done as if they’d happened yesterday.

But he had the upper hand. I couldn’t risk telling him what Essie had told me this morning while my head felt so patchy.

‘You’re wrong about her,’ I said. ‘She’s Mum’s mum and she’s an old lady. She just gets carried away sometimes.’

‘Old women aren’t a breed any more than teenagers are, otherwise you’d be the same as someone like Chloe.’ He got up. I knew what he meant by that without drawing any more out of him. He was always calling Chloe a scrag to wind me up. ‘I’m going to check on Mum.’

It was getting dark. My ceiling fan was just moving hot air around and around. You couldn’t fight heat like this and the only consolation was the knowledge that it couldn’t last. There’d be a storm, the heat would dissipate and everyone would be able to breathe again soon.

I tried to imagine the same thing happening with Dad. Walking back through the front door, putting his bags down, saying it had been a mistake. I pictured myself screaming at him – I could feel the pain of it in the back of my throat – letting him know how brutal it had felt, hugging him and crying and begging him never to do it again.

The longer I stayed in my room, the more difficult it felt to go and join Mum and Sam. Dad was my back-up, my friendly face. I put my head out of the window and looked up the narrow strip that opened out into the broad night sky. It was charcoal with a threat of orange – the promise of a storm. But as I twisted round towards the back of our house, I could see a single star. Was it north or south? Dad would know. He’d be able to tell me which direction the storm was coming from too.

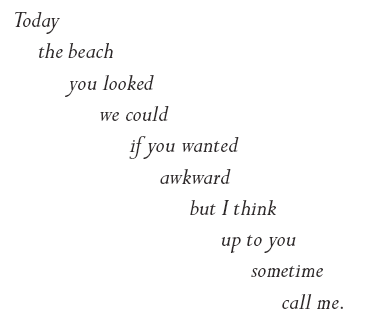

My voicemail alert went off again, muffled under my pillow, and I suddenly remembered hearing it earlier. The top of my head scraped against the window frame as I hurried to check who it was. I dialled and could only hear the blood pumping in my ears. Evan. And even though I listened hard to every word he said, they barely made sense; some were lost, others I had to string together again when the message had ended.

When I smiled I could feel where the tears had dried up on my face. But what now? What if I called him and Chloe was there? What if I’d got the message wrong or had misunderstood some vital part of it? I listened to it again. And again. What if I sounded like an idiot on the phone? What if I went on a date with him and it was everything I’d imagined hundreds of times?

I couldn’t help giggling. There was no way I could call him in this state. But knowing the message was there filled up the hollow space in my heart. I put the phone back under my pillow and stared at the photo of Essie. Somehow I knew what she’d have done if she were me. She wouldn’t hesitate. She wouldn’t have a single doubt. I wanted to know young Essie – someone that complex and strong had to have really lived. I needed to know her secrets, to find out how to be fearless like she was.

When I closed my eyes I saw Dad’s map of the route from our house to the bay. I breathed deeply, slowly, and traced my way back.

The next thing I knew, there was a thin strip of sunlight across my feet and a breeze skimming my legs. Warmth, breeze, pillow, head: I came slowly out of sleep, collecting my surroundings one by one. Then the front door slammed and I was instantly awake, stumbling across my room to see if it was Dad. Sam marched past without a glance my way, carrying a plastic bag crammed with food.

‘You’re awake then.’ Mum’s voice startled me. She was standing in the doorway of her room. She pulled her dressing-gown cord tight around her waist.

‘Yeah.’ I rubbed the sleep from my face. Mum’s eyes looked small and she had bunched-up tissues in her hand.

‘Sam, is that you?’ she called out.

‘Just making tea.’

I looked into Sam’s room. His bed was made and the clock on his DVD player read 8.25 am. I’d usually have left for school by now. Dad would have still been nagging Sam to get up as I walked out.

Sam came striding down the hallway, pulled his door shut and went back to the kitchen. ‘I’m doing sausages.’

I waited for Mum to react. We hadn’t had sausages for a year, not since her stupid friend Margot had made her watch a DVD about how they were made. But Mum sort of smiled as if sausages were the perfect thing.

‘I can’t believe he’s up,’ I said.

‘I don’t think he slept.’ She sighed. ‘Maybe he will after breakfast.’

I felt myself shrink at the concern in her voice. Sam would be loving this. He’d always clashed with Dad and now he had Mum to himself. All I could think was how much I wanted to hurt her.

‘Wonder how Dad’s doing,’ I said. I swallowed as soon as the words were out.

‘I think he’s probably just fine, Hannah.’

‘Sorry, Mum, I didn’t mean . . . I just don’t know what’s happening.’

Her shoulders deflated. ‘I know. Look, I’m going to need some time and a bit of support. Do you think you can do that for me?’ She sounded pretty unconvinced that I was even half capable of it.

‘Fine,’ I said, almost a whisper. I could smell the sausages now and my mouth was watering. There was no way I was going to touch them.

Instead, I showered and got dressed. Every sound from the back room registered somewhere inside me – their knives and forks, the kettle boiling again, someone stacking the dishwasher, the TV. Normal things were driving me crazy. I had to get away.

There was panic in my chest as I put on my uniform. Mum wouldn’t expect me to go and maybe that’s why I was. Or maybe I wanted other people to know what was happening to me, even if it was only the girls in my class. The dynamics between us had shifted since I became friends with Chloe but I’d known most of them since junior school. Girls like Seren and Naomi had even been to my movie night with my dad once or twice in the old days. And even if we hardly spoke now, telling them might mean something.

Then there was Chloe – I had to tell her, even though I could have written down right then and there what she would say. And school was near Essie. She had the key to the person I could turn into. My heart was still racing as I put my phone in my schoolbag and promised myself I’d call Evan, later and not here. I couldn’t do anything here.

My legs couldn’t keep up with how fast I needed to get away. I didn’t care how dumb I looked with my bag whacking against me, my shoes slapping the footpath. I hadn’t said goodbye and I half-expected Mum’s furious voice to come hurtling down after me. So when my tram slid into view, I started to run.

Making that tram was like a sign. For the first time in ages I didn’t bow my head and try to go unnoticed in my uniform that was different to all the other ones this side of the city. I just held on and caught my breath, rehearsing what I’d say when I walked into class. I’d be late so there’d be questions. Girls who usually never spoke to me would look up and see me properly. Old friends like Seren, Naomi, maybe Jess and Grace, would ask if I was okay. It was always that way when something big happened to someone in the class.

When Naomi’s parents split up we were still in junior school. We’d huddled around her every lunchtime. She’d cried a lot and we’d given her little presents and made sure she was never left out when it was time to pick partners. I couldn’t remember now how long that had lasted. But it’d been the same when Grace’s grandfather died. And when Seren told us she was going to a clinic for eating disorders.

It felt twisted to look forward to some attention but what else was I supposed to do? Naomi was fine now, so were Grace and Seren – this was just my turn. Maybe it would even be a way to get Chloe and me back into the group. Maybe a few girls would tell me I could stay with them if things got too bad at home.

I couldn’t get there fast enough.

I arrived at the end of recess so I waited, hidden, at the gates until everyone had gone back inside. Chloe had texted five times and I’d finally replied: be there soon. I walked across the empty courtyard, full of nervous energy.

It felt like so much time had passed since last year, not just a few weeks. Year 11. I hadn’t had the first thought about what that meant until now; I’d wanted to ignore it. Now that I was here, I didn’t feel like I was carving a path towards the end of school. It was as if the end of school was creeping steadily towards me, like a tide coming in. I was just watching it creep closer to my toes.

Now all the smells and sounds of school were seeping under my skin again. Disinfectant, books, herbal shampoo, floor polish, ‘Quiet, everyone’, clangs from the canteen, girls’ laughter, a whistle from the netball court. Everything was the same.

When I opened the door of my form room, the girls all looked up and there was a pause just long enough to make me realise that nothing was going to be different in here either. Sure enough, they all went back to what they’d been doing. All except Chloe. She slid up her chair from her usual rebel slump and gave me an extra-loaded look. I felt my cheeks go pink and walked self-consciously to my desk.

It was strange suddenly knowing that all the drama going on inside me wasn’t visible on my face. No one could see the pain and confusion of home. I’d have to spell it out – if I still wanted to. That seemed less likely now that Chloe was patting my chair and no one else was even looking any more.

‘Would you like to explain your absence, young lady?’ she said, eerily pulling off the voice of our form teacher, Mrs Gulliver.

‘You won’t believe it,’ I said.

As I sat down, Mr Inglewood, the Drama teacher, bowled into the room and made everything stop for real this time. His natural state was out-of-breath and it was pretty well documented, mainly on the inside of girls’ folders, that he was closer to our age than he was to any of the other teachers. He smacked a bunch of tatty folders on Mrs Gulliver’s desk, sat down in her chair and started going through them without a word. He was also known for being radical – at least he thought he was – like by not saying hello at the start of class. Some rebellion.

Some of the louder girls were teasing him. Lost your way, Mr Inglewood? That sort of thing. The level of excitement was infectious, even though he made me too nervous to enjoy anything about being in the same room as him. I was probably the only person there who’d have preferred to see Mrs Gulliver.

She was in her late fifties with hair as stiff as a bird’s nest. She wore polyester dresses in garish patterns, which gave her dark patches of sweat under her arms by midmorning. Whenever she spoke to the class a red rash crept from her collarbone to her hairline. I felt sorry for Mrs Gulliver but her nerves improved mine.

Mr Inglewood was in his twenties and had bed hair. It was as if he took looking casual very seriously. He had a tan, muscled arms and cute glasses, like a cross between a professor and a surfie.

‘Don’t usually see you in trackies, Mrs Gulliver,’ said Chloe. And over the giggling that followed she muttered, ‘Tool’. Mr Inglewood didn’t even look up. He’d written ‘Study Period’ on a piece of cardboard and propped it against some books on the desk. He looked completely unfazed by the heckling. I knew how much that would irritate Chloe and it made me nervous.

She pushed herself upright in her chair, squaring up to him. ‘What did you do last night?’ she asked him. There was a hint of the mean girl she could become if the wind changed. The rest of the room fell silent. ‘Sir? Can you hear me, sir? I just wondered if you did anything . . . fun.’

Mr Inglewood looked at Chloe. Then he looked at me and my heart stopped. Then at her again. ‘What do you think I did?’

Chloe looked at me as if to say: watch this. ‘Probably had a root.’

There were gasps and giggles all around us. I bent my head and studied a crack on my desk that was filled with some kind of gunk. With a biro I started to gouge it out. My skin felt like it had absorbed every drop of tension in the room.

I heard footsteps and saw that Mr Inglewood was now standing right in front of us. He put his hands on Chloe’s desk. I could smell his chewing gum.

‘Mrs Gulliver has called in sick. This is a quiet study period. I haven’t had a root, as you call it, in over a month. Are there any further questions, Chloe?’

Nothing.

Mr Inglewood walked away and returned to his folders, his face unreadable. The other girls took out their books in stunned silence. Chloe slumped down, looking unmoved, not defeated. She picked up the earphones that were dangling out of her bag and put one in. I reached out my little finger to stroke the back of her hand but she pulled it away.

I looked at her. Her hair was scraped back so the black roots gave way to bright blonde hair that would look tacky on most girls but looked sexy on her. Mum always said Chloe’s hair was like straw, like it was a final judgement on her character. Which it was.

‘Can we talk, sir?’ said Tess Edwards, class suck-up. ‘I mean, to each other – not you and me.’ Her sidekicks squealed like rodents. I looked round and caught a glance from Naomi, but that only served to make me realise how far apart I’d drifted from almost everyone.

Mr Inglewood replied without looking up. ‘Only if it’s interesting.’

‘It will be, sir!’ Tess pursed her lips in his direction and then looked to her crowd for approval. When the murmur gradually increased in volume, I decided to tell Chloe about Dad.

She was doodling on her notebook; concentric circles, minute distances apart, absolutely perfect and delicate. I reached over with my biro and wrote guess what? She drew a question mark. For a second I had no idea how to put it.

‘It’s my dad,’ I whispered. ‘He’s gone.’

She sat bolt upright and took out the earphone. ‘Shit! Oh my god, Han.’ She grabbed my shoulder and, by her expression, I realised she’d got the wrong end of the stick. It got Mr Inglewood’s attention too.

‘I’m sure Hannah has just told you something thrilling, Chloe, but keep it down.’

‘Her dad’s dead, okay? Jesus.’ She squeezed my shoulder hard again.

‘He’s not,’ I hissed. ‘Shut up, Chloe.’

‘Something you need to share, Hannah?’ said Mr Inglewood.

‘No. Sorry, it’s nothing.’

‘Let’s get on with minding our own business then.’

Chloe shook me.

‘Sorry!’ I whispered. ‘I just meant he’s left my mum. Gone. Geddit?’

‘Oh right.’ She let me go. ‘Ha, oh shit. I really thought you meant he was dead.’ She was smiling to herself and shaking her head, and then she started drawing circles again. ‘Has he got someone else?’ she said, after a while. I shrugged, I hadn’t even thought of that. ‘Hey, he’s not gay, is he?’

‘What? Why would you even say that?’

Mr Inglewood cleared his throat and gave me a look.

‘Calm down,’ Chloe whispered. ‘It’s just a possibility. Or do you actually know why he’s left? Your mum is totally uptight, right?’

‘I don’t know anything.’ I bit the inside of my mouth to stop myself from crying.

‘It’s probably not as bad as you think,’ said Chloe. ‘Some of us have been there and got the t-shirt. He’ll be back and it’ll all be fine, knowing you. Cheer up.’ She put the dangling earphone back in and handed me her other one. As I took it I stared at her fingernails, so overbitten they’d become lumpy, and suddenly I couldn’t help saying, ‘Also, your brother asked me out.’

It seemed to take her ages to turn her face in my direction. ‘Excuse me?’ That look floored me instantly. It wasn’t as if I could believe the words that had just left my lips, either. ‘Evan asked you on a date?’

‘I think so. Yeah.’

‘Are you sure? Haven’t you had a crush on him since you were, like, ten?’

‘Shut up, Chlo, I have not!’

I was nine. Evan and Sam had been best friends on the basketball team. Chloe and I weren’t even on each other’s radar back then.

Her face smoothed into something that looked like pity. ‘It’s not as if I’d mind, Han. It’s just that he’s a lot older than you and way more experienced. The last girl he hooked up with was twenty. Get me?’

I got her. Not that Evan was a lot older – he was the same age as Sam, who, to be fair, did seem like an oversized boy to me. But what I got was that I should never have said it out loud. Of course Evan wouldn’t really want me. It was a fantasy, something to think about at night so I could get to sleep. I was a kid with a balloon and I’d handed it to the wrong person to hold on to. Now it was floating up to the sky and out of sight.