THE REGIMEN LORD Luton’s party adopted in their refuge on the left bank of the Gravel was evolved through committee discussion, for Evelyn did not act dictatorially except when a decision might mean the life or death of his enterprise. He was a shining example of the ancient English principle of noblesse oblige, always mindful that as a noble man, he had the moral obligation to act honorably and generously toward those about him. In reaching decisions which might affect Fogarty, Luton even allowed the Irishman to participate in the discussions. ‘We’re civilized human beings,’ Luton was fond of saying, ‘and shall conduct ourselves accordingly.’

His style of leadership was manifested immediately as the Sweet Afton was safely drawn onto the shore, for he sought advice from all members of his team regarding the location and size of their winter quarters: ‘You’re to be living in them October to May, so share with me your best thoughts.’

He began by stepping off what he considered an adequate living-and-sleeping area, and marking the proposed corners with small piles of rocks, and as soon as he had completed this, Philip, Trevor and Fogarty lay down within the indicated space to demonstrate where the beds would have to be. When Luton himself dropped to the ground, inviting Carpenter to do the same, it became apparent that his first estimate for the size of the living area was ridiculously small, and he began to adjust its confines outward, warning his men: ‘With each step I take, your work is doubled.’ After some silent calculations, Carpenter agreed: ‘You know, men, he’s speaking the truth. Enlarging in any direction increases the work tremendously.’

Harry eased the problem by an ingenious suggestion: ‘Let’s pull the Sweet Afton up here to ground level, wedge her on her beam ends, and use her as one flank of our cabin,’ and Philip elaborated the proposal with one of his own: ‘Let’s orient the Afton so she protects us from the north winds.’ Carpenter countered: ‘Sound idea, Philip. But on this spot the winds will come howling down the Gravel out of the west,’ and the boat was shifted to provide protection in that quarter.

So Luton transferred his piles of corner rocks to the new terrain: ‘Harry, that was a splendid idea. See how it obviates one entire wall. A lot of chopping saved by that device and we can use the cabin jutting in as our cupboard.’ But Trevor Blythe chipped in with one of the best suggestions: ‘Let’s tie our largest canvas into this free end of the Afton. Lash it down securely and provide ourselves with a kind of protected storage area. Too cold for sleeping but valuable as a place to hold things.’ He smiled at Fogarty: ‘Say the frozen carcass of a moose you’ve shot.’ And this idea, too, was incorporated into the overall plan, with the canvas being erected immediately and tied securely to the Afton.

When Luton visualized his finished three-part winter dwelling he christened it ‘Our Hermaphrodite Igloo,’ and when the others protested that this part of the world had never known an igloo, he said: ‘In my storybooks there were nothing but igloos, and I’ve always wanted one,’ but Harry said more soberly: ‘You know, what we’ll have here is pretty much what the Eskimos along the oceanfronts have always had. A big canoe lashed down on its side to protect a kind of dugout in the earth. An entrance area much like this tent.’ Surveying the site, he said: ‘We’re in the grand tradition. And if thousands of Eskimos have survived the arctic winter in dwellings like this, so can we.’

Then the philosophizing and the frivolity ended, for the laborious work of building a fairly large cabin had to be accelerated against the coming of blizzards, and each of the men went studiously about his assigned tasks. Philip and Trevor were given ropes and sent to search for usable timbers from the bleached driftwood that cluttered the banks of the Gravel. Like all arctic rivers that passed through an almost treeless terrain, its shores contained such an inexhaustible supply of wood that Trevor cried: ‘Where can it come from?’ and naturally they asked Carpenter.

‘Simple. The banks here contain few trees. But up in the mountain, small forests.’

‘How does this tangle reach us?’

‘Winter snow blankets the forest. Spring thaw erodes the banks, and down come the trees. Voilà, the next flood brings them right to our doorstep.’ Within a short distance east or west along only the left bank they had at their disposal enough straight, fine wood to build a cathedral; choosing only the best timber, they worked far into the dusk hauling up to site level the wood that would be needed to face their cabin.

Carpenter and Fogarty, meanwhile, had taken upon themselves the most arduous task, that of felling and trimming the four stout poles that would form the corners of the cabin. With the expedition’s two hefty axes they sought out larch or spruce, girdled the chosen tree as close to ground level as practical, then took stances on opposite sides of the trunk and chopped away until the tree was felled. Then, by common agreement, they took turns resting and hacking off the lower branches and the unneeded crown of the tree, so that the end result was a sturdy corner post. It was strenuous work but necessary, for although driftwood of nearly proper size was available, both men feared it might have been so weakened by floodwater and bleaching and rough transit down the Gravel that it could not withstand winter blasts when wind pressures could be tremendous.

While the others were thus engaged in the demanding business of assembling the wood for their cabin, Lord Luton was painstakingly grubbing away with an improvised hoe-cum-scraper to provide a level base as the floor, and when that was finished to his satisfaction, he reached for the expedition’s sole shovel, and began the fatiguing task of digging four postholes for the corners. Almost immediately he learned that this was not like digging in a Devon garden where the loamy soil seemed almost to step aside to let the shovel pass. This was brutal, demanding work, each inch of niggardly soil defended by rocky deposits, and when he found that an hour of his best effort had produced a hole only a few inches deep, he summoned the others.

‘I’m not a shirker,’ he told them. ‘You know that. But this digging the postholes … really, I’m getting nowhere,’ and he showed them his pitiful results.

This led to serious discussion, with Lord Luton and Trevor Blythe suggesting that a meager footing might be adequate if properly buttressed by stones above the ground, and Carpenter and Fogarty counseling from their greater experience: ‘A corner post not properly sunk is an invitation to disaster.’ Now a subtle change came in the structure of the Luton party, for without ostentation or any move which might denigrate his leader’s position of authority, Tim Fogarty lifted the shovel from where Luton had dropped it, saying almost jocularly as he did so: ‘The fields of Ireland have far more rocks than those of England, Milord. Harry will need help chopping on that third post.’

When time came to attack the fourth post, Carpenter said: ‘Fogarty, give Evelyn a hand on that last one,’ and just as quietly as the Irishman had behaved when taking over the back-breaking work of digging the postholes, Harry took away the shovel and asked: ‘Evelyn? Where did you have in mind for this one?’ By these easy steps, Lord Luton was removed from command work but protected in his apparent leadership of the expedition as a whole.

It was Fogarty who suggested the solution to the chimney problem, for it was known in the arctic regions that to live in any cabin for seven or eight months without adequate ventilation for removal of smoke and noxious gases might not only damage eyesight but also result in death. Each winter in remote northern lands a handful of men, often two or three crowded in one small cabin, would perish in their sleep because there was no way for smoke to escape. Those who found their peaceful bodies in the spring would often say: ‘It’s an easy way to die, but not necessary.’

Carpenter and Fogarty knew it was obligatory to devise some arrangement which encouraged smoke and fumes to escape while preventing wind, rain and snow from entering. Since the team had not brought with them from Edmonton a stovepipe or anything that could be used as such, the men had to devise a reasonable substitute. Several ingenious ideas were suggested, including Trevor’s that the stove should be located in one of the corners, with that section of the roof left open and a wall of some sort erected across the corner to keep the smoke out. This proposal was rejected by Carpenter on the grounds that the chimney would have to be so huge an opening that there would be no upward draw: ‘The wind would howl down it and suffocate us all with smoke.’

Fogarty, at this point, found a collection of slablike rocks, rough on one side, smooth on the other, and he proposed constructing from them a stone chimney, wide at the bottom, narrow at the top, and when he put it together it was applauded by Carpenter, who pointed out: ‘Best feature is that the wooden wall will be faced by stone. Prevent fires, the kind that kill sleeping people in the north.’

In this quiet way Carpenter and Fogarty assumed effective command of the expedition during the period of building the winter retreat. They decided how deep the difficult postholes must be, where the chimney should be located, how beds should be constructed, and how the tent area should be incorporated into the whole, but even between them an unspoken struggle for leadership evolved, although neither trespassed the other’s prerogatives. When Harry decided that for maximum safety the cabin section must have an additional central post, Fogarty did not even comment, but when Harry himself started to seek out and cut down the added post, the Irishman quietly took command of the two axes and said: ‘Mr. Harry, time you learned the secrets.’ Off they marched to fell and trim the post, and when that job was completed, Fogarty also dug the fifth hole.

In this subtle manner each of the men acknowledged and performed his special function. Lord Luton decided the questions of policy, or anything requiring a resounding speech; Harry made the strategic decisions upon which the life and death of the expedition rested; Fogarty determined the practical ways to achieve ends with a minimum of oratory. And even the two young members differentiated their contributions, with Philip providing muscle and boundless energy when required, Trevor an ingratiating willingness to do the most menial jobs, such as washing dishes, gathering firewood, or taking waste to an improvised disposal dump. He also surprised the others at times with suggestions of the greatest practicality, as when he constructed and positioned three different sites from which the lanterns could be suspended, depending upon where their light was most needed for specific tasks.

When the log cabin was properly roofed, its sides erected and lashed securely to the corner posts, the two younger men rejoiced that the hard work was over, but Carpenter and Fogarty soon disabused them of that foolishness, for as Harry announced when the roof was in place: ‘Now the tedious work begins. All of us scour this land, miles in every direction, to find moss, and twigs and mud, especially the clayey type, for caulking every hole you see up there.’ And he pointed to the roof, where a hundred ill-matched joints provided entry for snow and rain and especially wind: ‘Caulk along the walls, too.’

Philip turned to the Sweet Afton and said jocularly: ‘I’ll caulk that wall,’ but he was one of the first down to the creek searching for mud, and far upstream he came upon one of those apparently random deposits of earth which had a modified clay consistency. He became the hauler of buckets of clay and river weeds to the other four as they strove to render their arctic home reasonably weatherproof.

After the talents of these energetic and willing men completed the building of their winter refuge, they had indeed what Lord Luton still called his Hermaphrodite Igloo, a weatherproofed cabin defended from blizzards by the resting Sweet Afton, enlarged by the unheated space of the strong tent, and warmed by the big wood-palisaded room from which the smoke escaped through Fogarty’s chimney and to which proper light was delivered by what Trevor Blythe called ‘my peripatetic lanterns.’

When the hard work was finished, mainly as a result of Carpenter and Fogarty’s solid leadership, Lord Luton was not only free to resume command but was also subtly invited to do so, and he began enthusiastically by lining out sensible rules for the governance of daily conduct in what he called ‘Our Kingdom of Kindred Souls’: ‘No one will lie abed all day unless he be ill and confined there. At least once each day every man will exercise. Harry, mark out a quarter-mile running oval and we’ll give it a whirl. I calculate we’re still well south of the Arctic Circle, so we’ll have hazy light for such running, but even during the darkness we must protect our health.’

Carpenter had several sensible suggestions: ‘We must change our socks at least twice a week and wash the worn ones in soap and hot water, else we’ll develop a horrible fungus. It’s not good to sleep in your clothes or to wear your underthings more than a week. The latrine is to be kept well back from the cabin, and I want to find no one just stepping outside the door and pissing.’

But both Luton and Carpenter directed their major planning to the avoidance of scurvy. ‘I’ve seen it,’ Harry said. ‘Hideous disease. Comes from an improper diet. Most people like us have had no opportunity to experience scurvy, so we underestimate it. You ever see it, Evelyn?’

Luton said he had not but he’d heard enough to frighten him. So Harry continued: ‘I saw it during a long sea voyage. We should’ve known better, but the men began to fall sick. Teeth drop out. Legs become necrotic.’

‘What’s that?’ Trevor asked, and Carpenter explained: ‘They die before the rest of the body dies. You punch your finger into the leg, and when you take your finger away, the hole stays there.’

‘What must we do?’ Philip asked, and Carpenter answered: ‘Canned fruit, pickled cabbage, the acid pills we bought in Edmonton. And we think that fresh meat provides just enough of what’s lacking …’

‘What is lacking?’ Blythe asked, and Carpenter said: ‘Various theories. We’ll know one day. So if anyone can shoot a deer, catch a fish or wing a duck, do so. Your life may depend on it.’

The five men, as congenial a group as could have been assembled for such adventure, spent their first two weeks of isolation in routinizing their existence. Snow did not yet cover the ground, and since this stretch of the Mackenzie received only moderate precipitation, snow, even when it did come, would not be a major problem, for as Carpenter explained: ‘Arctic regions like this receive far less snow than places like Montreal and New York.’

He laid out the running track, and he and Luton ran three laps morning and afternoon. The two younger men ran four laps in the late afternoon. Fogarty, who was often absent chasing game, ran on any day in which he had not walked extensively. And the health of all flourished. The latrine was dug, driftwood was collected from the riverbank and chopped to feed the effective little stove, and the men watched as the days swiftly shortened.

It was when the long nights started that the group showed itself to be exceptional, for under Luton’s wise leadership the men organized themselves into a kind of college in which each member except Fogarty would assume responsibility for a given night, during which he would expound upon something he knew, no matter how obscure or how apparently lacking in general interest. On one of his nights, for example, Luton explained the ramifications of the Bradcombe family and its role in English history. He told of the marriages, the scandals, the murders, the services his forebears had provided the crown. Later he and Harry spent more than an hour recalling fascinating examples of how the rules of primogeniture had operated in their family to ensure the longevity of the line. ‘It’s a thoughtful system,’ Evelyn said. ‘Eldest son inherits all—title … castles … land … lease to a good stretch of salmon river.’

‘Odd to hear you defending the system, Evelyn,’ young Henslow said, ‘seeing that you’re younger brother to Nigel, and he inherits all.’

‘But that’s what I mean, Philip. The law spells it out, item by item, so there can be no quarreling between Nigel and me.’

‘But aren’t you envious? Just a wee bit?’

‘I have my own title, an estate in Ireland, that’s adequate. Envy? I doubt I’ve ever had a shred.’

He then reviewed several fascinating accounts of how the principle of entailment had operated to protect important holdings in the Bradcombe family. ‘It’s like this. My father cannot sell or give away either the castle at Wellfleet or the two old houses in Ireland. They’re entailed. They must stay with the title.’

‘Interesting situation,’ Harry said. ‘Evelyn’s father can’t sell the Rembrandt or the Jan Steens, either. They’re entailed.’ He laughed: ‘You ever hear about the public scandal when my grandfather tried to sell off the pictures entailed to our family? Wanted the money to support an English actress he’d met in New York. Came home on the ship with her. Fearful scandal. The women in our family weren’t too worried about the actress but they raised hell about selling the Titian. Got the law to stop him.’

When it came time for Carpenter to conduct his first evening session, he surprised the group by announcing that on his nights he would read aloud the entire novel Great Expectations, which a tutor had told him was one of the best-constructed of all the English novels, and in time the others looked forward to his sessions, especially when the real cold set in and the river fairly crackled from the ice it was moving about.

They had become involved because this novel was composed of masterful visual images: the dramatic appearance of the convict in the churchyard, Miss Favisham and her moldering wedding cake, Pip’s boxing lesson, the wonderful scenes of London. ‘This is,’ said Harry, ‘a damned fine novel for a cabin near the Arctic Circle.’

Trevor Blythe gave a series of four lectures elucidating the magic of Shelley, Keats, Byron and Wordsworth, and because both his tutor and his mother had loved poetry, he had as a result of their pressures memorized long passages of the poets’ finer works, and he would sometimes sit with eyes closed, the light shining on his flaxen hair, and recite poems the others had known partially, and the cabin would be filled with the glorious music of the English language. Once on a very cold night when the land seemed to shudder from its weight of frost, with never a movement of air or breath of wind, he held a book open in his lap and without consulting it began reciting verses of Keats that he especially loved:

‘St. Agnes’ Eve—Ah, bitter chill it was!

The owl, for all his feathers, was a-cold;

The hare limp’d trembling through the frozen grass,

And silent was the flock in woolly fold.…’

He delivered the first forty lines from memory, then without breaking his rhythm he shifted to the book, but whenever he reached one of the sections he knew by heart, he closed his eyes again and filled the night air with those vast images that Keats had pressed upon his pages.

When Blythe reached the closing, with that marvelous line about the long carpets rising along the gusty floor, his listeners could see the lovers escaping and the drunken porter sprawled beside the gate. They could hear the door groaning and the warriors suffering nightmares. Such was the power of poetry that these long-dead words created living experiences, and the little cabin was alive with wonder.

On nights when Philip was responsible for the tutorial, as Lord Luton had dubbed these sessions, he could not compete in either wisdom or experience with his elders, and at first he was reluctant to try, but his uncle said firmly: ‘If you’re one of us, you must be one of us,’ and Philip, with fear that he was making an ass of himself, reviewed the courses he had taken at Eton, and because he had been above average in geometry, he began to give the men a review of that precise and beautiful subject, until Luton stopped him: ‘It’s fascinating, really, and we could profit from knowing what you know, but with your diagrams you’re using all our paper.’

By now Philip had gained confidence, so when he was deprived of geometry he turned to Greek mythology, and from that to the manner in which Charlemagne had established a great empire and then divided it among his sons. The older men listened attentively, happy to reacquaint themselves with subjects they too had studied more than a decade ago.

The hours of daylight, extremely brief at this latitude, were spent in vigorous outdoor activities—running, hunting, chopping—on those days when the temperature permitted, but when it skidded to fifty-below, all remained inside, edging ever closer to the fire to partake of the heat. Then the nights were twenty-four hours long, and orderly discussion under the flickering lights became treasured. The sessions had been under way for more than a month before Luton thought to include Fogarty as an instructor: ‘Fogarty, if we asked you to address this college on some subject about which you were an authority, what would it be?’ The Irishman knit his brow, then bit his lip and looked almost appealingly at each member of his audience: ‘I could talk about horses, but you gentlemen already know most of what I’d say.’

‘Go ahead,’ Carpenter urged. ‘We can never know enough.’

Fogarty, ignoring this encouragement, said: ‘But I doubt if you know much about poaching.’

‘You mean cooking eggs?’ Philip asked, to which Fogarty said: ‘No, I mean real poaching.’ And forthwith he launched into a detailed account of how a master fish-and-game thief worked: ‘Mind you, I was good at picking off a rabbit now and then, and that’s not an easy thing to do without making a noise, but me great love was to slip out on a moonless night and catch me a prize salmon.’

‘Salmon!’ Carpenter echoed in astonishment. His forebears had shot men trying to poach salmon on the streams they commanded and had sentenced more than one to Australia for the crime.

‘Aye, salmon, queen of the poacher’s art.’ And as he talked proudly of his skill and patience he began to reveal just enough about the specific scenes of his triumphs that Lord Luton could not avoid identifying the Irish rivers Fogarty had plundered with the ones he himself owned, and it dawned upon him that this prideful Irishman had long been stealing salmon from the very streams he had been hired to protect.

Shaken by this unpleasant discovery, at one point Luton asked: ‘Aren’t you speaking of the second pool below the stone bridge that General Netford built in 1803?’

‘Aye. The very bridge. They said it had been put there to aid the army in case Napoleon crossed into Ireland.’

Now Carpenter broke in: ‘That’s the pool my uncle Jack wrote about in his book on the upper-central rivers of Ireland. He named it Mirror Pool because it reflected the sky so perfectly.’

‘The same.’ For nearly a century the sportsmen of England had written books about their favorite salmon streams, until every stretch of river in the British Isles that hosted the precious fish had been described and evaluated. Men like Harry Carpenter could sit in India or along the Nile and recall without error entire stretches of river and recount proudly how some distant relative had landed his prize salmon in 1873. Now Fogarty, round-faced and unaware of the agitation he was creating, was relating the poor man’s version of the same chase: ‘I’ve never gone out within three days of a full moon, either before or after, and I used to advise young lads …’

‘You taught poaching?’ Trevor asked, and Fogarty said: ‘Not in the manner of a school, but if a young fellow of substantial character came to me with an earnest desire to make himself into a first-class poacher, I helped him learn the rules.’

‘What were the rules?’ Lord Luton asked with an icy reserve which hid his seething disgust at the revelations he was hearing, and Fogarty gave such a detailed reply that the evening became one of the best of the seminars, for interested students were listening to an expert with an amazing breadth of knowledge.

‘I stressed three basic rules, both in me own behavior and that of anyone I allowed to poach the streams I was controlling.’

‘You sold permissions?’ Luton asked, to which Fogarty responded: ‘Heavens, no! That was me first rule. “Never poach unless you need the fish and are going to eat it. Never sell it and don’t give it to anyone but your own family.” To poach for money would be quite dishonorable, don’t you agree?’

By such questioning, and by the controlled dignity of his approach to the stealing of salmon, Fogarty gradually brought his listeners into his confidence, and before long they were all participating in nightly forays and imaginary travels up and down the great fishing rivers of Britain. In particular, Harry Carpenter joined in the discussion, for he had fished most of the stretches and pools the Irishman was speaking of: ‘You mean, upstream of the one they call Princeps?’

‘Aye, that’s the one. With the willows on the far bank.’

It was not until Fogarty had traversed a dozen streams that Trevor Blythe asked hesitantly: ‘But isn’t this kind of poaching illegal?’ and Fogarty replied with no embarrassment: ‘I consider it taxation in reverse.’

‘What do you mean?’ Luton asked, and Fogarty explained with a self-incriminating frankness which astounded his employer: ‘The rich tax us poor people for almost anything we do, and a good poacher taxes the rich for a salmon or a rabbit now and then. It evens out, Milord.’

Fogarty’s beguiling revelations now lured even Evelyn into his net, for the noble lord began discussing poaching and rivers and the thrill of night fishing as if he too were participating in the challenging sport. At one point he asked: ‘What kind of fly would you use in well-rumpled water?’ and Carpenter chimed in with his own expert knowledge.

But the younger members of the class were not content with Fogarty’s answer on legality, and Philip persisted: ‘But it is illegal, isn’t it?’

‘Many things we do are illegal, or nearly so. Wasn’t it illegal for Major Carpenter’s grandfather to sell off the painting to please an actress?’

‘But the courts stopped him.’

‘Aye, and the courts stop poachers, if they catch them.’

‘How do you feel about that?’ Philip persisted, and Fogarty said: ‘I feel it’s a great, fine game. A test. A challenge to all that’s best in a man. His willingness to stand up for his rights.’

‘Rights?’ Luton asked, and in the bitter cold Fogarty replied very carefully: ‘I suppose that rivers were created for all men … to enjoy the fish God put in them. Laws have changed this, and maybe that’s all to the good, for thoughtful men like you and your father, Milord, you keep the rivers cleaned up and fresh for those who come after. But I believe that God sitting up there in judgement smiles when He watches one of His boys slip out at dusk to catch for his family one of the big fish that He has sent down, perhaps for that specific purpose.’

‘Isn’t it risky?’ Philip asked, and Fogarty pointed toward the much greater river that lay frozen outside: ‘Isn’t it risky for you to be challenging this river at this time of year?’

As winter deepened, life in the tiny cabin produced unexpected problems. When the spirit thermometer purchased in Edmonton stood at minus-forty-three the two younger men did not relish running the oval, but Luton and Harry missed only when heavy snow was actually falling, which was rare. ‘A man must keep his mettle,’ Luton said, and once when the temperature dropped to minus-fifty and Carpenter was held indoors with a nasty cold, Luton ran four laps alone, and came in perspiring: ‘My word, that was bracing!’

The outdoor running did create one situation which could have become ugly had not Luton taken stern steps. Philip Henslow, still inordinately proud of his rubber boots despite Irina Kozlok’s warning about their dubious utility in the arctic, tried doing his daily runs in them even though he knew that they provided almost no protection from the icy cold. In fact, their conductivity of cold was so immediate and complete that before he had run only a few steps in the bitter cold, his toes were colder than his nose, and that was perilous.

Out of pride in his choice of these boots and obstinacy in defending what he had done, he refused at first to acknowledge the resulting pain, but one evening when it became so intense that he winced when he took off his boots inside the cabin, his uncle heard the sudden intake of breath, looked down to see what had caused it, and guessed immediately that it was frostbite.

‘Let me see those feet,’ he said quietly, kneeling to feel the gelid toes and confirm the lack of circulation. After he looked closely he cried: ‘Harry! Come see this dreadful mess!’ and when Carpenter bent down he uttered a low whistle: ‘Another week of this and we’d have to cut off that left foot.’

When the others gathered around to look, they saw a pitiful example of frostbite: the skin an ashen white, peeling between the toes, ankles that delivered no pulse or movement of blood. And despite the fact that the feet had now been exposed to the heat of the cabin for many minutes, they were still shockingly cold.

But no one panicked. Carpenter said, giving both feet one more inspection: ‘They can be saved. Without question, Philip, they can be brought back. I’ve seen it done.’

Lord Luton issued a firm edict: ‘You will not wear those boots again this winter. You have heavy shoes and we have extra pairs of thin socks that you can wear inside.’ After turning away in disgust, he whipped about and said: ‘Harry, Trevor, you’re to inspect his feet every night to be sure they improve. I have a very queasy stomach when it comes to cutting off a man’s leg, especially a young man’s, but I shall do it if it needs being done.’

By placing Henslow’s feet first in cold, then cool, and eventually in warm water, the cure was effected, and all might have gone well had not poor Philip uttered an unfortunate final comment on the messy affair: ‘Irina warned me about those boots.’

This was more than Luton could tolerate. From a great height of moral indignation he glared down at his nephew and thundered: ‘She warned you? Damn me, I warned you. Harry warned you. And I heard Fogarty warning you: “Don’t buy fancy rubber boots for the arctic!” But you wouldn’t listen to us. You waited for her to warn you.’ By now he was shouting, but as he started to say: ‘Don’t you …’ he regained his self-control, and ashamed of himself, he dropped to his customary low-keyed voice: ‘Don’t use her name again, Philip. It offends me.’

As leader of the expedition, Luton felt that he must set an example by shaving daily, and he did, even though this entailed considerable effort and even discomfort. Fogarty, watching him struggle, said one morning: ‘Milord, I believe I could put a bit of edge on that razor.’ Luton replied: ‘You’re not here as my manservant,’ but since he winced with pain when he said this, Fogarty insisted: ‘Apply more lather, Milord, and let me have that thing.’ So while Luton soaped, Fogarty honed and stropped. Thereafter he tended the razor three mornings a week, not as a servant but as a friend, and he nodded approvingly when Luton told the others: ‘Men can turn sour in situations like this. The proper regard for the niceties is essential for morale.’

The men continued to honor the rule of urinating only at the latrine, and at the beginning they were careful to shave each day, but the tedium of doing so when temperatures were so low and space so crowded tempted first one and then another to forgo the daily shave, and once a beard started growing in earnest, all attempts to shave it off were surrendered. So by January everyone except Luton had a full beard, which was kept neatly trimmed by scissors applied in nightly sessions before one of the two camp mirrors; it was not uncommon to see a man tending his beard by the lantern while Carpenter read Great Expectations, which at the request of his companions he was reading for the second time.

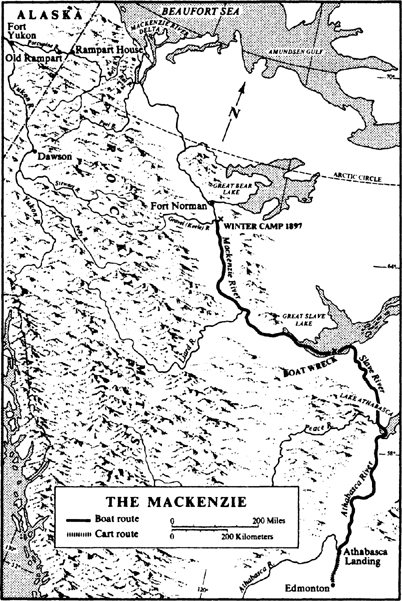

As Lord Luton ran his laps or worked alone at some outdoor project or ruminated at night after Harry ended that day’s stint of reading Great Expectations, he came to a conclusion which caused him pain: reviewing his pusillanimous behavior in not making a firm decision as to how his team was to bridge that awesome gap between the Mackenzie River to the east and the Yukon to the west, he saw clearly that he had been neglectful of duty in failing to direct his party up the Liard River, and one night he startled the others by rapping the table with his knuckles and crying: ‘Damn me, I should have grasped the nettle.’

‘What do you mean, Evelyn?’ Harry asked, and Luton replied: ‘On that long drift down the Mackenzie, I allowed myself to be mesmerized. My duty was to find our way over the Rockies to the Yukon and I failed the test.’

‘But, Evelyn, you still have three or four choices. The Gravel here. The ones at the beginning of the Delta. You’re far from shamed, and you’re even further from having let us down.’

Luton would not be consoled, for he better than any of the others knew that he had been delinquent in allowing the days to slip by as the Sweet Afton drifted so easily down the great river: ‘I feel like a Greek warrior who, on the eve of battle, takes refuge in nepenthe and dreams away the day of confrontation … sweet sleep of forgetfulness.’

In these days of self-flagellation it was curious that not once did he reflect on the fact that he was now by accident precisely where he ought to be when the rivers thawed in June: a quick push up the Gravel to where the boat could no longer make the bends, a swift sawing of the fine craft into halves, a brutally demanding but short portage over one of the best passes in the Rockies, an easy hookup with the Stewart River and into Dawson with no more trouble. Three or four times he had been reminded of this route, but the facts had simply not been allowed into his brain, for somewhere he had acquired a fixation that he must, as a matter of honor, sail to the end of the Mackenzie, then worm his way through whatever difficulties loomed while still remaining on Canadian soil. Ironically, the route up the Gravel would have satisfied most of those requirements admirably, but he failed to understand.

In his obstinacy he continued to berate himself until he was almost sick with self-recrimination, for failure lay heavily on a man like Luton. Once when he had captained a crucial cricket match against Sussex—at least he deemed it crucial—he had been forced to make one of those quick decisions which only cricket seems to produce: his team had a surprisingly comfortable lead, but to win the match outright he had to get Sussex out before time expired, so he made them follow-on, that is, bat out of turn in hopes that his bowlers could speedily dismiss them. But the Sussex rascals battled like demons, built up a big lead, declared before their last men were out, and made Luton’s team take the field and try to catch up. An awful thing happened: Sussex bowlers became like mortars, hurling deadly bombs at Luton’s men, so that instead of his having been clever in outsmarting Sussex, they outsmarted him and hurtingly. It was a disaster which he often recalled at night, ‘the arrogance of command,’ he called it, and its memory still stung.

He had the same regrets about having messed up the Mackenzie trip, and he refused to listen to Carpenter when his friend said truthfully: ‘Evelyn, it can all be salvaged. It’s to be a grand trip, come the thaw.’

Luton would not be consoled, and he felt so personally responsible for what he sensed as an impending disaster that he conceived a preposterous solution. ‘Gentlemen,’ he said one night before the prayers which he regularly led, ‘I’ve worked out the answer. It’s so simple, really. It’s less than fifty miles to the Hudson’s Bay post at Fort Norman …’

‘What’s that got to do with us?’ Carpenter asked, and Luton astonished him by replying: ‘They’ll know the secrets about the river systems up ahead. Maps and the like. And with their help I can make the proper decisions about what to do when the thaw comes.’

‘Evelyn,’ Carpenter said with studied patience, ‘don’t you realize that Fort Norman is downstream from us. Comes the thaw, we’ll go right past there. Couldn’t miss it if we wanted to. In thirty minutes ashore we can learn all they have to share.’

Luton, refusing to consider this sensible solution, not only continued to make plans to travel the fifty miles to the outpost but startled his team by insisting that he would go alone. When they remonstrated against the foolhardiness of this, he cut them short and said with the calm authority he knew so well how to exercise: ‘This is my responsibility, mine alone, and I shall make my studies.’

After one heated argument in which he said bluntly that he would be leaving next morning, Carpenter held private consultations with the two younger men: ‘Have you seen any indications of instability in Evelyn? I don’t mean this trip. Before? At home?’

‘None,’ Philip said firmly and Trevor had no comment, but when Harry continued: ‘What can ail the fellow?’ Trevor said gently: ‘I think he castigates himself for not having made firm decisions on the river, especially since he was so ready to do so coming across the Atlantic … and in Edmonton.’ When no one spoke, the young poet added: ‘He may feel he owes us a debt … not us but the expedition.’ Feeling himself entangled in arcane matters, he ended lamely: ‘Such self-accusations can be quite pressing, you know.’

On the morrow, Luton rose early, dressed in his warmest clothing, ate a hearty breakfast, then checked his rifle, his precious eiderdown sleeping bag, his supply of cartridges and his rations. When Harry took steps to follow with his own preparations for the foolhardy trip down the frozen Mackenzie, Evelyn said harshly: ‘I command you, Harry, to stay here and guard this encampment.’ Carpenter looked as if he were going to ignore the command, but Fogarty, to everyone’s surprise, interceded: ‘He knows what he’s doing, sir,’ and the noble lord, just turned thirty-two, struck out for the big river, made his way to its frozen center, and started the long snowshoe-and-ski push to Fort Norman.

Because he knew himself to be in excellent condition, he calculated that he could cover at least twenty-five miles a day and pretty surely reach the post at the close of the second day. He ate little and kept a sharp lookout for animals, not to shoot them but to record what wildlife was moving about at this time of year, but apart from a very few black and noisy ravens he saw little. Unaware of when day passed into night, he rested sporadically and on the second day kept traveling for nearly twenty hours down the breast of the great river, without incident: no fractures, no attacks by animals, just a normal caper down a vast river in thirty-degrees-below-zero weather and with sparse food. His spartan endurance put him into Fort Norman midway on the third day.

It had been for many years one of the farthest north of the Hudson’s Bay posts, and traditionally was manned by three or four French-Canadian employees of the famous old Company, men who spoke both French and English plus two or three Indian dialects, and a half-French, half-Indian fur trader or two. These latter were never to be called half-castes or half-breeds, designations they considered offensive; they were Métis, and the Canadian North could not have survived without their knowing services. At different posts, depending upon the character of the white managers, the Métis were treated either as fellow explorers with valuable skills or as lowly servants deserving little consideration. At Fort Norman, the one Métis present fell, for good reason, into the first category. He was a forty-year-old trapper and fur trader, who was treated almost as an equal by the three French Canadians in charge.

He was the first to spot Lord Luton striding alone down the middle of the Mackenzie, and his warning cry astounded the others: ‘Man coming right down the river!’ When the others ran to see, they expected to find someone near death, staggering up the long flight of wooden steps that led from their high ground down to the river’s edge and begging for water and food. They were amazed when, upon sighting them, he waved his rifle spiritedly, left the river, and actually ran up the score of steps, crying as he came: ‘I say! How good to find you chaps right where the map said you’d be.’

He did not stagger. He did not beg for food. Nor did he even accept the drink of water offered him: ‘I’m what you might say heading a small expedition. Five of us. Wintering in at the Gravel. All in super condition.’ Munching on a seabiscuit they provided, but not ravenously, he answered their questions. Yes, he had come down the river alone. Yes, the other three were Englishmen too. Yes, I did say there were five of us, the last’s an Irishman. Why had he come to Fort Norman? To seek counsel regarding the most practical way to slip over to the Yukon and the gold fields at Dawson, but only after the thaw came, of course.

One of the Canadians would report later: ‘It was like he had dropped by his corner tobacconist’s to pick up some Cuban cigars and the local gossip. Unconcerned. Unemotional. Damned good chap, that one, and we were nonplussed when he revealed under questioning that he was Lord Luton, younger son of the Marquess of Deal.’

It was a remarkable six days that Luton spent at the post, interrogating the traders, comparing notes with the Métis guide by relating the trip he’d taken, and formulating the intricate plans that would determine the third portion of his expedition. He found the conversation with the Métis the most rewarding. The man’s name was George Michael, and all pronounced his first name in the English fashion, his second as if it were the French equivalent, Michel, accenting the last syllable.

He told Luton that he had come north twelve years before from the District of Saskatchewan when some terrible battle with the English had driven his kind from their lands. Luton was stern in his questioning of Michael as to which Englishmen he had fought, and was greatly relieved when he understood that by ‘English’ the man had merely meant Canadian troops. Michael said that Luton was the first nobleman he had ever met, and in awe of Evelyn’s rank he called him ‘Duke.’ Then he spoke proudly of the noble blood in his own veins, the Indian blood, calling it the important half of his twin heritage. When the three white Canadians suggested that George Michael hurry back to the Gravel to assure the Englishmen that Lord Luton had arrived safely, he was delighted with the prospect of serving a duke and was disappointed when Luton said firmly: ‘No need. They’re all solid chaps. They’ll know in proper time I made it. I’m sure they expected me to.’

Then, with the aid of his hosts, he launched his advanced interrogations regarding the tangled rivers he would soon be attacking, and after listening to them only briefly he said: ‘I think I’ve found the four men in all Canada best qualified to advise me.’

‘First of all, Lord Luton …’

‘Please call me Evelyn, since we’re to be working at this for some spell.’

‘You’re not in a bad position where your camp is now, at the confluence of the Gravel. You’re aware, I’m sure, that when the thaw comes, you can head up the Gravel and portage to the Stewart. Then all’s fair and a soft run home.’

‘I had rather fancied the route just beyond the Arctic Circle.’

The men were not displeased by this rejection of their advice, for his preference brought him into the territory they knew best, but when they were alone one old-timer with the Company asked: ‘Do you think he knows what he’s doing?’ and another said: ‘No Englishman ever does,’ but the third man cautioned: ‘This one may be different, he’s a proper lord.’ The second pointed out: ‘Lords are worst of all,’ but when the third man reminded them: ‘This one did walk near fifty miles right down our river,’ they all agreed that he merited consideration.

In preparation for their next meeting with Luton they drafted a set of maps for him, marking with a heavy line the route that two of them had used in getting from Fort Norman over the crest of the Rockies and down into the important American trading station at Fort Yukon, within easy striking distance of the gold fields. And the men combined to drill into him, thrice over, the important decision points.

‘My lord, there’ll be markers to help you leave the Mackenzie and find your way into the Peel. That’s crucial. Everything depends on your getting out of this river and into the smaller system to the west.’

Another man broke in: ‘Crucial, yes, but the next turn is the one that counts. Many miss it, to their woe. You’ll find the Rat River on your right, not big but the secret to success. Because it’s there you saw your boat in half, and the vital push begins. Up to the headwaters of the Rat, a short portage over the divide, and you’re in the Bell. And then,’ the speaker’s voice relaxed, ‘you’re in a straight run home.’

‘To where?’ Luton asked, and when the man said: ‘The Porcupine, which takes you straight into Fort Yukon, good water all the way.’

‘Oh, no,’ Luton said, drawing himself away from his ardent instructors. ‘I’d really not care to reach my goal through American territory.’

This caused some consternation, two of the men judging such a restriction to be childish, the other two agreeing that it was sensible for a patriotic Englishman to want to keep his money and loyalty within the Empire, but it was George Michael alone who saw the solution to this impasse: ‘Duke, the Porcupine she is no problem. Turn right, you go into America. Turn left you stay in Canada, all way to Dawson.’

Now the others became enthusiastic, applauding Michael’s sensible statement: ‘And what’s better, halfway to Dawson there’s a kind of village, two, three cabins where trappers lay over in storms. Always food there.’ The men agreed with unanimous encouragement that their noble guest should follow that intricate but relatively easy Canadian route to the gold fields.

They were surprised, therefore, when Luton pushed aside their hand-drawn maps and turned to one large one published by the government: ‘I had rather thought we’d stay with the Peel. You can see its headwaters will bring us very close to Dawson.’

This arrogant dismissal of their reasoned advice, and the proposal of a route completely contrary to what they had been advising, caused a hush, but then one of the Canadians inspected the map closely and said dryly: ‘What I see is that you’d be heading into one of the highest passes in this part of the Rockies,’ and another seasoned traveler warned: ‘That would be foolhardy, sir.’ Even George Michael agreed: ‘Duke, I travel on the Peel one time with the current helpin’ me. Very swift. Hills each side river, they are close, close. To go your way, against current, those tight spots, they will cause you much trouble, you bet.’

It was obvious that their arguments against staying with the Peel had not dissuaded him, and it was also clear that as a member of the nobility and leader of his expedition, he did not care to prolong the argument. The Fort Norman men saw that he had made up his mind and they knew that extreme hardship and perhaps tragedy would ensue, but that would be his problem, not theirs.

But when Luton was away working on his notes, one of the three French Canadians asked: ‘What makes Englishmen so stubborn … so blind to facts,’ and the oldest man, who had tangled with them many times in various parts of Canada, said: ‘Maybe that’s what makes ’em Englishmen. They’re born to do things their way,’ and the other one admitted grudgingly: ‘Maybe he’s right. We know we can go Rat-Bell route. Maybe he’ll find a better way startin’ with the Peel,’ and the experienced man warned: ‘In a game, never bet against an Englishman,’ and the third one said: ‘But this isn’t a game,’ and the oldest said: ‘For them it is. Else why would he walk down the Mackenzie in coldest winter? To prove he could do it. He’ll go up the Peel just to prove we were wrong,’ and they burst into laughter.

Apart from those differences of opinion regarding routes, the six-day visit had been a respite, appreciated by everyone, and the Canadians were regretful when Luton said: ‘Tomorrow I must head back and get our team prepared for the thaw.’

They asked if he had any conception of what happened to a frozen river when the ice broke up, and he replied: ‘I’ve heard it can be somewhat daunting.’

‘Unbelievable,’ they said, ‘and on this river, the worst of all.’ Taking him to their front porch atop the rise, they explained a peculiarity of the Mackenzie: ‘It runs from mountains in the south to very flat land in the north. When the sun starts back in March, it melts the headwater ice first and starts those waters flowing. Then it melts the high plateaus, setting free whole lakes of water, and every warming day it releases more and more water far to the south, while our part of the river up here in the north remains frozen tight. And what happens?’ the men asked, looking to see if Luton had understood.

‘Stands to reason, the waters flood in under the ice and dislodge it.’

‘Dislodge is not the word. It explodes the ice from below. It throws it about like leaves in a storm. Chunks bigger than you could ever imagine are thrown up as if they weighed no more than sheaves of straw. Believe me, sir, stand well back when the Mackenzie breaks its bonds. But it is a sight no man should miss.’

Next morning when he proposed to start his fifty-mile journey back to the Gravel, he was surprised to find that the Hudson’s Bay men were united in insisting that George Michael accompany him: ‘Common sense dictates it. As head of your expedition you dare not risk an accident.’

‘I made my way here. I can certainly …’ When they refused to alter their plan, he asked: ‘But how’s he to get back?’ and the Métis said with a big smile: ‘No trouble. I will walk,’ and Luton thought: To give me comfort he’ll walk near a hundred miles. With great reluctance he allowed George Michael to accompany him.

As the two men climbed down the wooden stairway to where the frozen river waited, the Canadians gave them three cheers and fired volleys in the air. Lord Luton turned and raised his hand in salute to them and their flag, a heroic outpost in this frozen wilderness.

It was providential that George Michael accompanied Luton back to the Gravel, for as soon as they arrived at the tent-cabin he cried: ‘Oh, Duke! You ’ave made terrible mistake!” In the dim light of day he ran about identifying scars on rocks and trees, and pointing in dismay toward the Gravel, the Mackenzie and the cabin.

Seeing his agitation and having had proof of George Michael’s good sense, Luton stopped the man’s running about and asked: ‘What is it, Michael?’ and the Métis replied, with fear clouding his face: ‘You are in great danger, Duke. When thaw comes, ice here in Gravel and ice out there in Mackenzie, she will crash, sweep everything away.’ Then he kicked at the upturned Sweet Afton and with wild gestures indicated huge blocks of ice coming down the Gravel and battering the Sweet Afton and the cabin into small kindling: ‘Then what you do? No boat? No cabin? What in hell you goin’ do?’

He would not delay even half a day, for the safety of this expedition led by a man he had grown to like and respect was of vital importance to him, and from long experience he knew that in these parts the preservation of the boat was paramount. Showing the men how to construct rollers from driftwood tree trunks, he marshaled all the ropes they could provide, used their shovel to smooth a pathway to higher ground, and with all hands pushing and hauling he tore the Sweet Afton away from her snug position as part of the cabin and dragged her to a spot well above where the crashing ice might be expected to reach.

Tireless, he then began the removal of the entire living area, even the latrine, to higher ground, and as he and Carpenter started to move the beds he stopped and said dramatically: ‘You stay down here, some night soon when you asleep, the ice she come and we don’t see you never no more.’ Two nightfalls later the expedition was finally housed in a barely adequate substitute for the original cabin but one at a safer elevation. His task done, Michael sat heavily upon a rock, leaned back to allow the weak sun to reach his face, and said: ‘I very hungry. We eat?’

At the first resting period Lord Luton made a proposal that surprised the others: ‘Harry, take the shovel and scar out an exercise track for us up here next to our new cabin,’ and Philip protested: ‘The one down there’s perfectly good. No trouble to run down for our daily spin.’

‘Ah!’ Luton said with some force. ‘A great deal of trouble. Minus-forty and stiff breeze, which of us will want not only to run our circuits but also to run down that hill and back to do so? You, Philip, would be the first to demur. I can hear you arguing with me: “But, Uncle Evelyn! It’s bitter cold out there!” And the exercise you miss could well be the one that would doom you. Harry, mark it close to the shack.’ When it had been delineated, Evelyn was the first to utilize it, but George Michael, watching him run in the bitter cold, told the others: ‘He must be crazy. Nobody in Fort Norman run in the cold … summer neither,’ and Harry said quietly: ‘I’m sure they don’t.’

The Métis remained with the Englishmen a full week, during which he helped them complete the reconstruction of their living quarters and went hunting with Fogarty, whom he recognized as a kindred spirit. They were a pair of highly skilled hunters and brought a large moose to the far shore of the Mackenzie—Fogarty told the others: ‘He did it, not me’—and next morning after profuse thanks from Luton plus a gold sovereign he was gone, a lone figure striking out for the north, rifle slung across his back, right down the middle of the great river.

With George Michael gone and the camp, thanks to his assistance, at a safe elevation, life returned to its routine, with Lord Luton giving only the most fragmentary report on his extraordinary visit to Fort Norman: ‘We studied the maps and they copied several for us, so we’re in firm shape,’ and he displayed them briefly. Carpenter quickly saw that Luton had apparently decided to follow the Peel into some rather high terrain, and he asked quietly: ‘Wouldn’t picking our way through those smaller rivers and that lower pass be preferable? I was told in Edmonton …’

‘Strangers can be told anything,’ Luton snapped as he took back his maps.

One morning, apropos of nothing that had been said before, he told the men: ‘At Fort Norman, I felt absolutely naked. Those huge men with their beards as big as bushes. Said they never shaved after the fifteenth of October—tradition, they assured me.’ Then, looking about the cabin, he pointed to Trevor Blythe, whose beard was so skimpy and faded-straw in color that it made a poor show: ‘I say, Trevor, want to borrow my razor and scrape that foolish thing off?’ but the younger man parried the suggestion by admitting, with some embarrassment: ‘I simply abhor shaving. At home I allow Forbes to do it for me, and I wish he were here now.’

But in some ways it was Blythe who accommodated most perfectly to the winter isolation, for he was attuned to the changes of nature and relished what he was witnessing: ‘Have you ever seen more heavenly pastel colors than those out there? I feared the night would be perpetual, but these midday hours are superb. Just enough light to bathe the world in beauty.’

He attracted the admiration of everyone by an astonishing accomplishment. The men were surprised that even in the remotest and coldest parts of the arctic, ravens appeared, huge black creatures with an ugly cry. ‘What do they live on?’ Blythe asked. ‘In this frozen waste what can they possibly find to eat?’ In time, the ravens were eating scraps which he provided and shortly one of the more daring was coming close to his feet and snatching crumbs from the snow. To the other men, all ravens looked alike, but Trevor found in this one some identifying sign, and whenever the bird appeared, Trevor lured it always closer. Othello, he called it, and it seemed as if the raven recognized its name and responded to it.

One morning while Trevor was outside feeding Othello, the men in the cabin heard a soft cry: ‘I say, come here. But quiet.’ And when they opened the door slowly they saw the raven perched on Trevor’s left arm eating crumbs which the young man offered with his right hand.

‘Remarkable!’ Luton cried, whereupon the bird flew off with a slight beating of its black wings, but on subsequent days it returned, and grew bolder, until finally it elected Blythe’s left shoulder as an assured resting place. When the others saw this extraordinary spectacle of a young man swathed in arctic clothing, flaxen hair exposed, with a raven perched on his shoulder, all silhouetted against the blazing white of the snow, they tried to lure the bird, but Othello, sensing that Blythe was the one to trust, stayed with him.

The men had agreed back in Edmonton, when it became obvious that they must spend a winter in the far north, that they would keep a record of how extreme cold and prolonged night affected them, and they learned to their relief that any healthy man who did, as Luton insisted, ‘observe the niceties,’ survived rather well. ‘There is disruption,’ Luton conceded in his notes. ‘We eat less, seem to require more water, and have to guard against constipation. We also suffer minor eye irritation from incessant lantern light. But we can detect no negative mental effects, and as the worst part of winter approaches, we have no apprehensions.’

Fogarty in the meantime was scouring the countryside for game, and sometimes the men would see him approaching the far side of the deeply frozen Mackenzie at the conclusion of some foray to the east, and they would watch his distant figure grow larger. They would study closely to see if he signaled for them to cross over and help him drag home a side of caribou, and if he did wave his arms in triumph, they would pile out, cross the river, and grab hold of whatever it was he had dragged behind him, and that night their cabin would be rich with the smell of roasting meat.

As January waned, Carpenter warned his companions: ‘February is the testing time. No part of the year colder than February.’ In 1898 it was especially bitter along the Mackenzie, with the spirit thermometer staying below forty for days at a time, but when the cold was most oppressive Carpenter would say: ‘When it breaks, we’ll have summer in winter!’ and he was right, for in late February the cold mysteriously abated and the men had a respite as lovely and as welcome as any they had ever known.

The thermometer rose to four-below, and since there was not even a whisper of wind, it was indeed like summer. Harry and Philip actually ran their laps with shirts off, chests bare, and experienced no discomfort. Othello made two turns of the snow-packed course on Blythe’s shoulder, and Carpenter accompanied Fogarty on a long excursion to the other side of the Mackenzie, where they bagged a moose.

This reassuring respite heightened the spirits of the men, who restudied their maps and made plans for when the spring thaw would allow them to resume their journey to the gold fields. ‘What those bearded ones at Norman reminded me,’ Luton said, ‘is that when we have to saw our boat in half, it might well be at a spot where there’s no timber to be had to shore up the open end. So what we must do on our way downriver, as soon as it’s ice-free, is bring on board any logs that look as if they might be sawn into short planking.’

‘And where do you calculate the site for sawing the Sweet Afton apart might come?’ Carpenter inquired, not in unduly curious fashion but merely to prepare his thinking, and Luton pointed almost automatically to a spot well up the Peel River. Carpenter was about to launch one final protest against taking a route which was sure to be perilous, but before he could voice his objections, Lord Luton anticipated them, swept up his maps, and disappeared before Harry could force the issue.

So the vital decision was never submitted to an honest criticism and evaluation. When Harry studied his own maps in secret they reinforced his apprehensions about the inherent dangers in trying to force a way up the Peel: The entire trip on the river is against a current which has to be swift. The rapids cannot be easy to portage if there’s no path to walk on shore. And those damned high mountains at the end. Not promising, not promising at all.

Now when he did his daily turns on the new track, some fifty feet higher than the old, he calculated the odds on each of these impediments. At the end of one imaginary survey he ruefully cast the score: Impedimenta barring the way, nineteen; Lord Luton’s party, nothing. And he could foresee no way to change those odds unless Evelyn entertained a revelation when he faced that lonely spot where the Rat River led to safety across the low divide: If he refuses to see or to listen, we’re doomed.

He was certain of this, and yet he did not enforce his judgment upon his cousin. Luton was younger than he by six years and less experienced in the field by seven or eight major explorations. He was in no way superior to Harry in intellect or in his university performance. He was courageous, of that there could be no question, but he had never been tested under fire the way Harry had been. And although he had a stern moral fiber, what some would term character, it had not yet been required to assert itself in time of real crisis, the way Harry’s character had been tested in India and Africa.

With the scales weighing those virtues that really mattered in Carpenter’s favor, why did he defer to his younger cousin? Because in the prolific and noble Bradcombe family it was the custom out of time to pay deference when facing difficult decisions to the man who held the marquisate of Deal, and remote though the possibility was, Harry knew that Evelyn might one day be that man. This rule had served the family well, and if an occasional marquess had been a ninny, most had not, and Carpenter could see that when Evelyn had a few more years under his belt, he would be eligible, if called upon, to be one of the best. This expedition to the gold fields of Canada could be the final testing ground that would make Lord Luton a whole man, one forged in fire, and Harry Carpenter would stand by him in the testing period, for in that regard, he, Harry, represented all the Bradcombes. Their leader was under scrutiny and they stood with him.

With the arrival of warmer weather in April the men assumed that the Mackenzie would begin to thaw, and it was Blythe, least experienced outdoorsman of the group, who pointed out: ‘Fellows! It’s still ten degrees below freezing!’ and Philip replied: ‘But it feels like summer.’

It did, and the realization that the winter hibernation would soon be coming to an end spurred the men to start casting up their assessments of what their adventure in the arctic winter had meant. Lord Luton took it upon himself to make the summary statements in the official log, and he came close to the truth when he wrote:

As I look back on this splendid adventure, I see that we were a team of five who respected nature and wished to test ourselves against the full force of an arctic winter. Harry Carpenter had wide experience in frontier situations in all climates. My nephew Philip Henslow was a keen sportsman and a reliable shot. His friend Trevor Blythe displayed an uncanny aptitude for domesticating wild ravens, something never before attempted to our knowledge, and even our trusted ghillie, Fogarty from Ireland, had an unmatched knowledge of the way of salmon. I had traveled to many distant areas, loved boxing and cricket and the dictum of Juvenal: Mens sana in corpore sano.

At the beginning of our long hibernation we laid down sensible and healthful rules which all obeyed, and as a result we suffered not one serious illness or accident. Rigorous daily exercise seems a sure preventative for the idleness of an arctic stay, and our experience is that it should be enforced out of doors even in the roughest weather. Among other benefits, it inhibits constipation.

But the remarkable fact about our stay is that all team members displayed unusual and unflagging courage. Never were spirits allowed to fall or pettiness to invade our daily regimen. When meat was needed, our members were willing to roam very far afield, even under the most daunting circumstances. Hard word was greeted almost as a friend, and we proved once more what honest Englishmen can accomplish in adversity, and even Fogarty caught the spirit, for his extended forays in search of provender were little less than heroic. Harry Carpenter was an older exemplar without parallel of such deportment and our two younger men were faultless, displaying great promise for future development.

In all modesty I make bold to claim we were a gallant bunch, and the arctic was powerless to defeat us in our quest.

When the others heard these lines read aloud, they protested that in the coda Lord Luton had not mentioned his own laudable behavior, and when he disclaimed the right to any special notice, Harry Carpenter took the journal and wrote, reciting the words aloud as he did:

‘The other members of the Lord Luton party wish to record the fact that in all contingencies their leader was salutary in his own display of courage under difficult situations, none more so than when he went on foot fifty miles in each direction, alone and in the dead of winter with the thermometer at minus-forty and storms brewing, to find us data regarding our next target. In this feat, performed during days that allowed only two hours of daylight, he performed as none of the rest of us could have.’

There were murmurs of assent when Carpenter laid down his pen, but as he himself looked at the final words of his encomium he realized that he had omitted the salient truth of Luton’s journey: And he returned from his venture without having listened to a word of the advice given him.

In May came unmistakable signs of approaching thaw, but it was not until June that Fogarty set out for one last hunting trip on the opposite bank of the Mackenzie; he returned immediately up the Gravel, shouting: ‘Gentlemen! Come see the river!’ When they did, they witnessed one of the most savage displays of nature, for the various tributaries lying far to the south where the sun returned early had long since thawed and sent their burden of melt-water and floating ice crashing northward. Now, as this icy flood reached areas still frozen, the whole river began to writhe and crack and heave. With astonishing reports, like the firing of a battery of cannon, thick ice off the mouth of the Gravel, locked there since October, broke asunder in wild confusion.

‘Good God!’ Luton shouted. ‘Look out there. That one’s as big as a house,’ and when the men stared toward the middle of the Mackenzie they saw that he was wrong. It was bigger than three houses, a huge chunk of ice, and as it ground its way past the mouth of the Gravel, pulverizing the smaller floes which that small river had contributed, the men gained an appreciation of what an arctic river could do when it was shattered by the surges of spring.

Blythe and Henslow stood side by side, watching in awe as a gigantic iceberg came thundering down the river, holding embedded within its massive walls of ice a collection of intertwined evergreen trees that it had ripped from a hillside eight hundred miles distant. On it came, ‘a frozen forest,’ Trevor said as he tried to imagine the journey the trees had made, ‘That iceberg must hold a thousand bird’s nests, and when they come flying back to find their homes the landlord will tell them: “We’ve moved them to the shores of the Arctic Ocean. Start flying north.” ’

For more than an hour the two young men watched little forests floating past, but then their attention was directed to Carpenter, who shouted: ‘Look what’s coming to greet us over here!’ and everyone turned to see what their relatively tiny Gravel could produce, for tumbling down it came a monstrous block of ice traveling at harmful speed. As it roared past, twisting and turning, it swept with awful crunching force right over the spot where the original cabin had been, and with such grinding power that it would have reduced both craft and cabin to pulp.

No one, watching the total erasure of their former homesite and means of escape from this wintry prison, could keep from thinking: My God! If we had remained in that spot! And all recalled George Michael’s rhetorical question: ‘What would you do if you lost your boat?’ Carpenter summed up their reactions: ‘Thank God, Evelyn did go to Fort Norman and bring back that Métis. We escaped a terrible trap.’

And then Philip shouted: ‘Look at that one!’ and down this meager stream, the Gravel, came one more block of ice, as big as any on the Mackenzie, and it was rolling in such grotesque fashion that it struck and dug deeply into the right bank, opposite where the watchers stood, and gouged out a huge chunk of bank, leaving behind four trees with roots torn loose, so that their trunks and branches, lying parallel to the earth, reached far over the surface of the river but not quite in it.

Carpenter, who had seen this phenomenon in Africa, warned those about him: ‘Extremely dangerous, that. They call them sweepers.’

‘Why that?’ Philip asked, and Harry said: ‘Because if you come down this river in an open boat—and what else would you have on a stream this size—you grow careless, and those low branches reach out and sweep you right off your boat, and the current is so swift you can’t climb back. Take care with sweepers.’

One night during the waiting period it came Trevor Blythe’s turn to conduct the seminar, and since this was more or less the termination of their long confinement, he offered a surprising but unusually profitable exercise: ‘Under my goading, we’ve talked a lot about poetry, I’m afraid, and often we’ve referred to the inventive lines with which poems begin. Things like “My true-love hath my heart and I have his” and “Tell me where is Fancy bred.” Such lines are keys that unlock gracious memories, and they don’t have to be all that fine as poetry. Their job is to set bells ringing.

‘As we drifted down this great river, I was pestered by a ripping pair of lines:

Ye Mariners of England

That guard our native seas!…

Ever since we left the Athabasca Landing, I’ve been such a mariner,’ and after laughing at himself he cited a few more effective opening lines: ‘ “It is a beauteous evening, calm and free” ’ and ‘ “Oft in the stilly night.” ’

But then he shifted sharply: ‘I’ve come to think that how a work of art ends is just as important as how it begins. A good opening entices us, but a strong finish nails down the experience.’ Now he had to consult Palgrave, for not even he was as familiar with the good closings as with the lyrical openings. He deemed one of blind Milton’s to be impeccable: ‘ “They also serve who only stand and wait.” ’ But as a young man in love, a condition he had so far revealed to no one, not even the young lady, he also favored: ‘ “I could not love thee, Dear, so much,/ Loved I not Honour more.” ’

But he surprised his listeners by praising extensively the rough, harsh ending of one of Shakespeare’s loveliest songs: ‘It has one of the perfect openings, of course: “When icicles hang by the wall” and it continues with splendid lines which evoke winter, such as “And milk comes frozen home in pail” and “When roasted crabs hiss in the bowl.” But after all the niceties of the banquet hall have been exhibited, he closes with that remarkable line which only he could have written: “While greasy Joan doth keel the pot” to remind us that somebody has been toiling in the kitchen.’

Trevor then came to his conclusion: ‘Point I’ve been wanting to make, the real poet has the last line in mind when he writes his first, and there’s no better example of this than the ending to that special poem of Waller’s whose opening stanza I praised many months ago, the one beginning “Go, lovely Rose!” Do any of you remember how it ends? Neither did I, and I’m not going to trust my memory now. It’s Palgrave, Number Eighty-nine, I believe.’

While fumbling for the page, he said: ‘Remember how the first three stanzas go. In the first the rose is commanded to go to his love. In the second it’s to inform her that young girls, like roses, are put on earth to be admired. In the third the rose is to command her to come forth and be admired. And now the wonderful last verse:

Then die! that she

The common fate of all things rare

May read in thee:

How small a part of time they share

That are so wondrous sweet and fair!’

Silently the men contemplated the misery of death, then Lord Luton spoke: ‘A noble ending to a grand winter,’ and as he looked at the two young men he said loudly: ‘Do you realize how precious this winter will have been when we look back upon it? Philip, Trevor! You’ll tell of this to people who will never have guessed that a majestic river like this existed!’ He smiled at Harry and added: ‘So shall we all.’

Harry did not return the smile, for while the others prepared joyously to plunge into the swollen Mackenzie for a triumphant run downriver to its junction with the Peel, he could not erase from his mind a segment of map he had memorized. It showed that if one ascended the Gravel to its headwaters and made a relatively short portage across the divide, one found oneself at the headwaters of a considerable river, the Stewart, which did meander a bit but which finally deposited one right on the Yukon, less than fifty miles upstream from Dawson City and the gold fields. And it’s downstream all the way, once you reach the Stewart, he told himself, and he became so convinced that Evelyn was doing exactly the wrong thing in turning his back on the Gravel that on the very morning of their breaking camp he launched one final appeal: ‘Evelyn, you have studied the maps more closely than any of us. Surely you can visualize what a sensible union the Gravel and the Stewart achieve?’

Luton refused to listen: ‘I have indeed studied the map … memorized it … and I visualize instead the Peel, which leads directly to our destination.’ And so the five men set forth.