ON 19 JULY 362, Jewish delegates from Syria and Asia Minor—but not, apparently, from the patriarchate in Tiberias—arrived at Antioch for a meeting with Emperor Julian. They had been summoned as part of Julian’s great plan for the empire. To replace the newfangled religion of Christ, he wished to see sacrifice offered in all the imperial domains to the One God, the Supreme Being, who was worshipped under many names: Zeus, Helios, or God Most High, as he was sometimes called in the Jewish Scriptures. Already in each region, Julian, as pontifex maximus of Rome, had appointed pagan priests to oppose the Christian bishops; towns which had never adopted Christianity were given special privileges, and Christians were being gradually removed from public office. Although the emperor also disapproved of some aspects of Judaism, he admired the Jews’ fidelity to their ancient faith. His teacher Iambilicus had taught him that no prayer could reach God unless it was accompanied by sacrifice; the Jews, however, were no longer able to celebrate their ancestral rituals. This could only be damaging to the interests of the empire, whose well-being depended upon the support of God.

When, therefore, the Jewish elders were assembled before him, Julian asked them why they no longer offered sacrifice to God according to the Law of Moses. He knew the reason perfectly well, but he was deliberately setting the stage for the Jews to request the resumption of their cult. The elders duly explained: “We are not allowed by our Law to sacrifice outside the Holy City. How can we do it now? Restore to us the city, rebuild the Temple and the altar, and we shall offer sacrifices as in days of old.” This was exactly what Julian wanted to do, not least because it would deal such a bitter blow to the Christian argument that the defeat of Judaism proved the truth of their, the Christians’, scriptures. Now the emperor told the elders: “I shall endeavor with the utmost zeal to set up the Temple of the Most High God.”1 Immediately after the meeting, Julian wrote to Patriarch Hillel II and to all the Jews of the empire, promising to make Jerusalem a Jewish city once more: “I will rebuild the holy city in Jerusalem at my expense and will populate it, as you have wished to see it for these many years.”2

There was wild enthusiasm in the Jewish communities. The shofar was blown in the streets, and it seemed as though the Messiah would shortly arrive. Many Jews turned viciously on the Christians, who had lorded it over them for so long.3 Crowds of Jews began to arrive in Jerusalem, thronging its streets for the first time in over two hundred years. Others sent contributions for the new Temple. The Jews built a temporary synagogue in one of the ruined porches on the Temple Mount, and Julian may even have asked the Christian inhabitants to restore the property that belonged by rights to the Jewish people. He appointed his scholarly friend Alypius to supervise the building of the Temple and began to amass the materials. Special silver tools were prepared, since the use of iron was forbidden in the construction of the altar. On 5 March 363, Julian and his army left for Persia, where, the emperor believed, the success of his campaign would prove the truth of his pagan vision. When he returned, he promised that he would personally dedicate the Temple as part of the victory celebrations. After the emperor’s departure, Jewish workers began to uncover the foundations of the old Temple, clearing away the mounds of rubble and debris. Work continued throughout April and May. But the patriarch and the rabbis of Galilee regarded the venture with deep misgiving:4 they were now convinced that the Messiah alone could rebuild the Temple. How could a Temple built by an idolater be blessed by God, and what would happen if Julian did not return from Persia?

Now it was the Christians’ turn to contemplate an imperial building program that wholly ignored their claim to the Holy City. For fifty years the church had seemed to be going from strength to strength, but Julian’s apostasy had shown Christians how vulnerable they really were. The old paganism still flourished, and over the years a great deal of pent-up hostility had accumulated against the church. In Paneas and Sebaste the pagans had actually rioted against Christianity when Julian’s edicts were published. His plan to restore the old religion was not an impractical dream, and the Christians knew that. On the day that the work began on the Temple Mount, the Christians of Jerusalem assembled in the Martyrium to implore God to avert this disaster. Then they processed to the Mount of Olives, singing the Jewish psalms that they had made their own. From the spot where generations of Christians had meditated on the defeat of Judaism, they gazed aghast at the purposeful activity on the Temple platform. They had become so accustomed to seeing the decline of Judaism as the essential concomitant to the rise of their own church that the Jewish workmen below seemed to be undermining the fabric of the Christian faith. Bishop Cyril, however, begged them not to lose hope: he confidently foretold that the new Temple would never be completed.

On 27 May, Cyril’s prophecy seemed to come true. An earthquake shook the entire city in what seemed to the Christians to be a display of divine wrath. Fire broke out in the vaults underneath the platform, as gases, which had been gathering in the underground chambers, exploded, setting fire to the building materials stored there. According to Alypius’s official report, huge “balls of fire” (globi flammarum) erupted from the ground, injuring several workmen.5 By this time, Julian had already crossed the Tigris and burned his bridge of boats. He was now beyond the reach of communications, so Alypius probably decided to wait for further news from the front after this setback. A few weeks later, Julian was killed in battle and Jovian, a Christian, was proclaimed emperor in his stead.

The Christians made no effort to conceal their jubilation after this “miracle”: there was talk of a giant cross appearing in the sky, stretching from the Mount of Olives to Golgotha. Other people claimed that crosses mysteriously appeared on the clothes of many pagans and Jews in Jerusalem. These extreme reversals could only intensify the hostility between Christians and Jews. Jovian banned the Jews from Jerusalem and its environs yet again, and when they came to mourn the Temple on the Ninth of Av, the rituals had acquired a new sadness. “They come silently and they go silently,” wrote Rabbi Berakiah, “they come weeping and they go weeping.”6 The ceremonies no longer ended in thanksgiving and a bracing procession around the city. Christians regarded these rites with a new harshness. When the biblical scholar Jerome saw this “rabble of the wretched” process to the Temple Mount, he decided that their feeble bodies and tattered clothes were outward signs of their rejection by God. The Jews “are not worthy of compassion,” he concluded,7 with a callousness that showed scant regard for the teaching of Jesus and Paul, who had both declared charity to be the highest religious duty. To Jerome’s fury, by the end of the fourth century the Jews seemed to have recovered their nerve. They still proclaimed that the ancient prophecies would be fulfilled. They pointed to Jerusalem, confidently predicting: “There the sanctuary of the Lord will be rebuilt.”8 At the end of time, the Messiah would come and rebuild the city with gold and jewels.

Christians did not forget that they had nearly lost their holy city. They could no longer take their tenure for granted and were determined to establish such a strong Christian presence in Palestine in general and Jerusalem in particular that they could never be dislodged again. The character of the city changed as the Christians gradually began to achieve a majority. By 390 the city was full of monks and nuns and foreign visitors came to Jerusalem in large numbers,9 returning home with tales of the Holy City and enthusiastic descriptions of its impressive liturgy; others stayed on permanently. Jerome was just one of the new settlers who came from the the West toward the end of the fourth century: some had come as pilgrims, others as refugees from the Germans and Huns who had started to bring down the Roman empire in Europe. This influx from the West increased when Theodosius I, a fervent Spanish Christian, became emperor in 379. He arrived in Constantinople on 24 November 380, with an entourage of pious Spaniards who were committed to implementing his aggressive orthodoxy. In 381, Theodosius put an end to the long Arian controversy by declaring Nicene Christianity to be the official creed of the Roman empire. Ten years later, he banned all pagan sacrifice and closed down the old shrines and temples. Some of the women in the court, such as Empress Aelia Flacilla, had already distinguished themselves in Rome by attacking pagan shrines and building splendid churches in honor of the martyrs. Now they brought this militant Christianity to the East.

The chief focus of Theodosian Christianity in Jerusalem was the hostel on the Mount of Olives which had been founded in 379, the year of Theodosius’s accession, by two Western Christians: Rufinus, an old friend of Jerome’s, and Melania, an aristocratic lady of Spanish descent. She had embraced the ascetical life after her husband’s death and become a formidable Christian scholar. As soon as her children were old enough to take care of themselves, she had left Europe and toured the new monasteries in Egypt and the Levant before coming to Jerusalem to found her own monastery. On the Mount of Olives, men and women could live a life of prayer and penance, teach, study, and provide shelter and hospitality to pilgrims. Melania and Rufinus involved themselves closely in the life of the city, and their monks and nuns took a full part in the developing liturgy, acting as interpreters to pilgrims from the West who could not understand the Greek used in the services, nor the Aramaic of the local translators. Melania and Rufinus were both passionate Nicene Christians and maintained close links with the court at Constantinople and with the monastic movement abroad.

Jerome and his friend Paula stayed at Melania’s hostel during their pilgrimage to Jerusalem in 385, and it became their model for their own community in Bethlehem. At first, Jerome had praised Melania to the skies, but he was an irascible man, not given, as we have seen, to the practice of Christian charity, and soon he had permanently fallen out with her as a result of a theological quarrel. After that Jerome had never a good word to say about the Mount of Olives establishment. He sneered at its comfortable lifestyle, which reminded him of the wealth of Croesus;10 he stigmatized the worldliness of Melania’s community, with its cosmopolitan atmosphere and links with the court. The “solitude” of Bethlehem was far more suitable as a setting for the monastic life, he argued, than the pagan bustle of Jerusalem, “a crowded city with its command, its garrison, its prostitutes, actors, jesters, and everything which is usually found in cities.”11 The Bethlehem community was more close-knit and introverted, consisting in the main of admirers of Jerome. For years he fought a bitter campaign against Melania, but her reputation spread in the West and pilgrims continued to be inspired by her example.

One of these was Poemenia, a member of the royal family, who also toured the monasteries of Upper Egypt before coming to Jerusalem in 390. There she built a church on the summit of the Mount of Olives to mark the spot of Christ’s ascension into heaven. Poemenia’s church, which has not survived, was surmounted by a large, glittering cross that dominated the skyline. It was a round church, enclosing a rock on which pilgrims believed that they could see Christ’s footprint. Other buildings were also appearing in the vicinity. At one end of the Kidron Valley, a church was erected on the site of the tomb of the Virgin Mary; at the other end of the valley, some monks had decided that the tomb of the Bene Hezir was the grave of James the Tzaddik, and they converted it into a church. In about 390 an elegant church was erected on the site of the Garden of Gethsemane. Theodosian Christianity laid great stress on shrines, and these churches created new facts in front of Jerusalem. The pagans of the city now had to confront an increasingly assertive Christian presence, as new churches appeared and new sites were annexed inside and outside the walls.

Christians also took over the city on their principal feast days, when huge crowds spilled out of the churches onto the streets, marching all around Jerusalem and the surrounding countryside. Christianity was no longer a clandestine faith: people no longer had to meet unobtrusively in one another’s homes to celebrate their Eucharist. They could develop their own public liturgy. In Rome they used to gather around the tombs of the martyrs, weeping and shouting aloud as they listened to an account of their passion and death. They paraded with their bishop through the streets from one church to another, gradually imposing their own sacred topography upon the old pagan capital. There was a similar development in Jerusalem, which was starting to transform pagan Aelia into a Christian holy city. We see this in the writings of Egeria, a devout Spanish pilgrim who arrived in Constantinople in 381, just as the bishops were assembling for the council which would make Athanasius’s doctrine of the incarnation the official teaching of the church.12 Egeria shared to the full the Theodosian enthusiasm for shrines. She embarked on a lengthy tour of the Near East, venturing as far afield as Mesopotamia, treating the Bible as a sort of Blue Guide. Whenever she and her companions identified a sacred site, they would read the appropriate passage from Scripture “on the very spot” (in ipso loco), a phrase which recurs constantly in her account. Egeria was far more effusive than the taciturn Bordeaux pilgrim: she was obviously thrilled to see the places which most Christians could only imagine. The Bible came to life before her eyes. As Cyril had suggested, proximity to the place where a miracle or a theophany had occurred brought these distant events closer and the Bible reading became a sacramental reenactment that made the past a present reality. The only difference between this new Christian ritual and the old Temple cults was that the latter had commemorated mythical events of primordial time, while the New Testament episodes had occurred in the relatively recent past.

Once Egeria had arrived in Jerusalem, however, this holy sight-seeing gave way to a formal liturgical participation in the sacred events of Jesus’s life, death, and Resurrection. The whole Christian community would take part in carefully planned processions to the appropriate spot. Egeria speaks of immense crowds filling the courtyards of Golgotha and flowing out into the streets. On September 14 the city was filled to bursting point with monks and nuns from Mesopotamia, Syria, and Egypt who had come to celebrate the eight days of Enkainia, the festival which celebrated the dedication of Constantine’s New Jerusalem and Helena’s discovery of the True Cross. Enkainia also roughly coincided with Sukkoth, the anniversary of Solomon’s dedication of the Jewish Temple, which Christians saw as a foreshadowing of the later, more glorious event. Pilgrims had to be in good physical condition: liturgical celebration in Jerusalem involved more than decorous hymn singing and listening to sermons. The participants were required to spend whole days and nights on their feet, marching from one holy place to another. They celebrated Christmas week, starting on 6 January, with a solemn procession each night from Bethlehem to Jerusalem. They would not arrive at the tomb, now enclosed in the recently completed Anastasis Rotunda, until dawn, when they would take only a short rest before attending a four-hour service. On the afternoon of Palm Sunday, crowds gathered at the Eleona Basilica on the Mount of Olives for a service, followed by a march down the mountainside, through the Kidron Valley, and back into the city. Bishop Cyril rode behind the procession on a donkey, just as Jesus had done when he arrived in Jerusalem, the children waved palm and olive branches and the congregation sang hymns, chanting periodically: “Blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord.” Egeria tells us that the procession moved slowly, so as not to weary the people, and it was late at night before they arrived at the Anastasis. Pentecost was especially exhausting. After the usual Sunday Eucharist, Cyril led a procession to the Sion Basilica to celebrate the descent of the Spirit in ipso loco, but, not content with that, the crowds spent the afternoon walking to the top of the Mount of Olives in memory of the Ascension. After that they processed slowly and gently back to the city, stopping at the Eleona Basilica for vespers, an evening service in Constantine’s Martyrium, and, finally, midnight prayers back at the Basilica of Holy Sion.

These celebrations inevitably changed the Christian experience. Hitherto there had been little interest in the individual events of Jesus’s earthly life. Jesus’s death and resurrection had been seen as a single revelation, a mysterium which had disclosed the way that human beings, through the Logos, would themselves return to God. But now the monks, nuns, clerics, laity, and pilgrims of Jerusalem were being encouraged to focus on specific incidents for some considerable time. In the week leading up to Easter, for example, they followed in Jesus’s footsteps, reading at the appropriate places the gospel account of Jesus’s betrayal by Judas, his last supper, and his arrest. It was an extraordinarily emotional experience. Egeria tells us that when the crowds listened to the story of Jesus’s arrest in the Gethsemane Church, “there is such a moaning and groaning of all the people, with weeping, that the groans can be heard almost at the city.”13 There was a new sympathy for Jesus the man; the crowds were learning to live through the experience of his suffering with him, day by day, and were acquiring an enhanced appreciation of what this pain had meant to him. Eusebius had told Christians not to dwell upon the physical form which the Logos had temporarily assumed during his brief sojourn on earth, but the Jerusalem liturgy was changing all that. Christians were now concentrating on Christ’s human nature. Ever since Constantine had established the New Jerusalem, the rock of Golgotha had stood near the tomb: every day there were separate prayers around the rock as well as at the Anastasis, so people were getting used to meditating on the Crucifixion as a distinct event. On Good Friday the faithful would process one by one to the small chapel behind the rock to kiss the relic of the True Cross. Eusebius had never shown much interest in the Crucifixion, but now these emotive celebrations were forcing Christians to consider the human implications of Christ’s death and to meditate upon what it meant for the incarnate Logos to die.

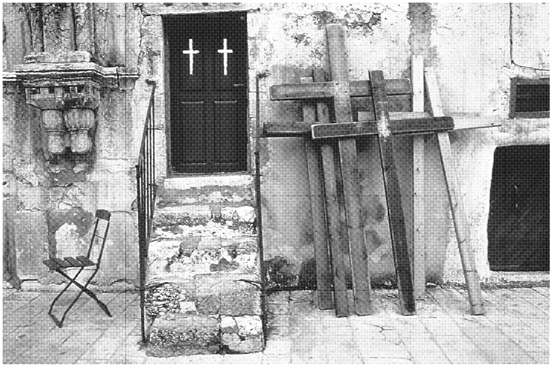

Processional crosses stacked against the wall of the Ethiopian monastery on the roof of the Holy Sepulcher Church. Since the fourth century, Christians have marched through the streets of Jerusalem following in Jesus’s footsteps, and thus acquired an enhanced appreciation of the meaning of the incarnation.

Matter was no longer something to be cast aside; Christians were beginning to find that it could introduce them to the sacred. Pilgrims were developing a very tactile spirituality. They wanted to touch, kiss, and lick the stones that had once made contact with Jesus. When Jerome’s disciple Paula arrived at the tomb, she first kissed the stone which had been rolled away from the cave on Easter Sunday morning. Then, “like a thirsty man who had waited long and at last comes to water, she faithfully licked the very place where he had lain.”14 Paula’s contemporary Paulinus of Nola explained: “The principal motive which draws people to Jerusalem is the desire to see and touch the places where Christ is present in the body.”15 In other parts of the world, Christians experienced the divine power when they touched the bones of the martyrs, which embodied their holiness. The great Cappadocian theologian Gregory of Nyssa (338–95) pointed out that “they bring eye, mouth, ear, and all senses into play”16 Because God had been incarnated in human form, Christians had now begun to experience the physical as sacred and able to transmit eulogia (“blessing”). Gregory had visited Palestine himself, and though he had misgivings about the new vogue for pilgrimage, he admitted that the holy places of Jerusalem were different. They had “received the footprints of Life itself.”17 God had left a trace of himself in Palestine, just as perfume lingered in a room after the wearer had left. Pilgrims now took rocks, soil, or oil from the lamps in the holy places back home with them; one particularly fervent pilgrim had actually bitten off a chunk of the True Cross when he had kissed it on Good Friday. People wanted to make the holiness of Jerusalem effective and available in their hometowns.

Christian archaeology had begun with the spectacular dig at Golgotha. Now new excavations unearthed the bodies of saints and biblical heroes in other parts of Palestine. What was thought to be the body of Joseph the Patriarch was exhumed at Shechem, now known as Neapolis, and transferred to Constantinople. Jerome described the crowds who lined the roads when the bones of the prophet Samuel were carried from Palestine to the imperial capital; they felt as though the prophet himself were present.18 These expropriations of holy bones were an attempt to give the new Christian city of Constantinople a link with the sacred past that it would otherwise have lacked. Yet it was also an attempt to appropriate Jewish history: if the church was, as it claimed, the new Israel, it followed that these saints of the Old Covenant would be more truly at home in Christian territory than in cities frequented by the perfidious Jews. In 415 the Eastern emperor Theodosius II publicly reprimanded the Jewish patriarch Gamaliel II and stripped him of the rank of praefectus praetorio. The emperor thus set in motion a process that would bring the patriarchate to an end in 429, a step which, the ecclesiastical leaders believed, would hasten the inevitable demise of Judaism.19

In December 415, a parish priest made another archaeological discovery that seemed connected to the humiliation of the Jewish patriarch. Lucian, a presbyter of the village of Kfar Gamala on the coastal plain, had a dream in which Rabbi Gamaliel I, the teacher of St. Paul, appeared to him. The great Pharisee told Lucian that he had been secretly converted to Christianity but had kept this hidden out of fear of the Jews. When Stephen, the first Christian martyr, was killed outside the walls of Jerusalem for attacking the Torah and the Temple, Gamaliel had taken the body and buried it on his estate here at Gamala; later he himself was buried beside the martyr, together with Nicodemus, the young Jew who had once had a clandestine meeting with Jesus by night. The next day Lucian made some investigations and unearthed three tombs with Hebrew inscriptions, just as the rabbi had told him in his dream. Immediately he informed his bishop of this wonderful discovery.

Now it happened that Bishop John of Jerusalem was presiding at a church council at nearby Lydda, now called Diospolis. He had been deciding the fate of the British monk Pelagius, who had scandalized the Western Christians in Jerusalem by denying the doctrine of original sin, though John himself could see little harm in Pelagius’s theology. As soon as he heard Lucian’s news, however, he set off posthaste to Kfar Gamala, accompanied by the bishops of Sebaste and Jericho. When Stephen’s tomb was opened, the air was filled with such sweet scent, Lucian recalled, that “we thought we were in Paradise.”20 This was a common experience at the tombs of the martyrs. The body of the saint who was now in heaven had created a link between this world and the next. The place had thus become a new “center” of holiness that enabled the worshippers to enter the realm of the sacred and gave them an experience of the power and healing presence of God. At the martyrs’ tombs in Europe the faithful were healed by the tangible aura of holiness which filled the shrine when the story of the martyr’s passion was read aloud; a sweet fragrance filled the air, and people cried aloud as they experienced the divine impact.21 Now Christians started to arrive at Kfar Gamala from all over Palestine, and seventy-three sick people were cured.

John, however, had no intention of allowing Kfar Gamala to become a center of pilgrimage but was determined to use this miraculous find to enhance his own position. Like his predecessors, he wanted to improve the status of the see of Jerusalem and had recently rebuilt the basilica on Mount Sion, the Mother of all the churches. Now he decided that it was only right that Stephen should be buried in this new basilica, on the site of the church where he had served as a deacon, and on 26 December the bones were transferred to Mount Sion. Yet this discovery, which brought healing and holiness to Christians, was inherently inimical to Judaism. Stephen had died because he had attacked the Torah and the Temple; he had been a victim of the Jews. The revelation that the great Rabbi Gamaliel, the ancestor and namesake of the present patriarch, had been a closet Christian undermined the Jewish integrity of the patriarchate. Still, Christian growth was seen as inextricably involved with a rejection of the parent faith.

The court of Theodosius II was consumed by a passion for asceticism. Indeed, it resembled a monastery, and Pulcheria, the emperor’s sister, lived in its midst as a consecrated virgin. Inevitably this reign saw the resurgence of monasticism in and around Jerusalem. Jerome’s hostility had so poisoned the Holy City for Melania and Rufinus that they had returned to Europe in 399, though family considerations had also played a part in Melania’s decision to leave. But in 417 her granddaughter, usually known as Melania the Younger, arrived in Jerusalem with her husband, Pionius. Together they founded a new double monastery on the Mount of Olives for about 180 monks and nuns. Melania also built a martyrium, a shrine for relics, next to Poemenia’s church. Twenty years later, Peter, a prince of the Kingdom of Iberia,22 who had been living in the imperial court of Constantinople, arrived in Jerusalem to found a monastery at the so-called Tower of David, which was in fact part of the Herodian tower Hippicus. He also brought Melania a gift of relics for her martyrium on the Mount of Olives.

Monks had also started to come from all parts of the Christian world to colonize the Judaean desert, drawn to this beautiful but desolate region by the sanctity of Jerusalem. One of the earliest of these monastic pioneers was the Armenian monk Euthymius (d. 478), who founded about fifteen monasteries in spectacular locations between Masada and Bethlehem. He was regarded by his contemporaries as a second Adam: his career was thought to have launched a new era for humanity.23 In their monasteries, the monks planted gardens and fruit trees, making the desert bloom and reclaiming this demonic realm for God. Each settlement was thus a new Eden, a new beginning. There monks could live a paradisal life of intimacy with God, like the first Adam. The monasteries were thus a new kind of holy place, part of a Christian offensive against the powers of darkness, where people called to the monastic life could return to the primal harmony and wholeness for which human beings continue to yearn. Soon Latins, Persians, Indians, Ethiopians, and Armenians were flocking to the Judaean monasteries. One of Euthymius’s most influential disciples was Sabas (439–531), a Cappadocian who had deliberately chosen to settle in Judaea because of its proximity to the holy places. As with all true sacred space, the site of his monastery was revealed to him by God in a vision, and for five years Sabas lived alone, high up in a cliff, nine miles south of Jerusalem overlooking the Brook Kidron. Then disciples began to join him, each living in a separate cave until gradually the area became a new monastic city in the desert. Living alone, denying their natural need for sex, sleep, food, and social intercourse, the monks believed that they would discover for themselves human powers that God had given the first Adam; they would thus reverse the effects of the Fall and share in God’s own holiness. Yet Sabas also had another aim. “It was necessary for him to colonize [the desert],” explained his biographer, “to fulfill the prophecies about it of the sublime Isaiah.”24 Second Isaiah had promised that the desert would burst into flower and become a new Eden: now Sabas and his monks believed that these holy settlements would bring the final redemption foretold by the prophets one step nearer, except now the recipients would not be the Jewish people but Christians.

Like most of the institutions of Christian Jerusalem, therefore, the new monastic venture had an inbuilt hostility toward the Jews. This had become tragically apparent during the pilgrimage of Empress Eudokia, the wife of Theodosius II, in 438. Eudokia was a convert to Christianity: she was the daughter of a distinguished Athenian philosopher and was herself a learned woman. As an intelligent convert, she does not seem to have shared the apparently ingrained Christian aversion to Judaism and had given the Jews permission to pray on the Temple Mount on holy days other than the Ninth of Av. Naturally this must have appalled many of the Christians, though Eudokia’s high rank made it impossible to protest. Her astonishing edict gave some Jews hope of an impending redemption: it was said that a letter circulated to the Diaspora communities urging Jews to come to celebrate the festival of Sukkoth in Jerusalem so that the Kingdom could be established there.25 Sukkoth happened to coincide with the empress’s visit to Palestine. On the first day of the festival, while Eudokia was in Bethlehem, Jews began to congregate on the Temple Mount in large numbers.

They were not alone. The Syrian monk Bar Sauma, who was famous for his violence against Jewish communities, had also arrived in Jerusalem for Sukkoth. He was careful to stay innocently in a monastery, but other monks were also lurking on the Temple platform while the Jews were processing around its ruined courts waving their palm branches for the first time in centuries. Suddenly, Bar Sauma’s biographer tells us, they were attacked by a miraculous shower of stones which rained down upon them from heaven. Many Jews were killed on the mount; others died as they tried to escape, and their bodies filled the streets and courtyards of the city. But the survivors acted quickly, seized eighteen of Bar Sauma’s disciples, and marched them off to Bethlehem, still clutching their palm branches, to confront Eudokia with the evidence. The empress found herself in great danger. Monks rushed into the city from their desert monasteries, and soon the streets of Jerusalem and Bethlehem were packed with an angry monastic mob who made it clear that if Eudokia passed sentence on the prisoners they would burn her alive. When the imperial legate arrived from Caesarea, six days later, he was afraid to enter Jerusalem and was only permitted to examine the prisoners in Bar Sauma’s presence. A compromise was reached when the governor’s investigators arrived with the news that the Jews who had been killed on that fatal night had died of natural causes. Bar Sauma sent a herald through the streets proclaiming: “The cross has triumphed!” The mob took up the cry, and Bar Sauma was carried in a jubilant procession to Mount Sion, where he celebrated a victory mass in the basilica.

Eudokia’s visit ended on a more positive note. On 15 May 439, she dedicated a small shrine in honor of St. Stephen outside the northern gate of the city on the very spot where it was believed he had been executed. The next day she carried a relic of the saint to Melania’s martyrium on the Mount of Olives before returning to Constantinople. Despite her rather checkered experiences there, she had been happy in Palestine, and when she had a disagreement with the imperial family in 444, especially with the emperor’s pious sister Pulcheria, she was banished to Jerusalem. Because of her high rank she became the ruler of Palestine and built many new churches and hospices in and around Jerusalem: one at the Pool of Siloam, where Jesus had healed a blind man, one in honor of St. Peter on the site of Caiaphas’s supposed residence on Mount Sion, and one in honor of Holy Wisdom on what was mistakenly thought to have been the site of Pilate’s Praetorium in the Tyropoeon Valley, west of the Temple Mount. Eudokia also built a palace for herself at the southeast corner of the Temple Mount, beneath the “Pinnacle of the Temple”; later this residence would become a convent for six hundred nuns. She is also said to have built a new city wall for Jerusalem, which extended the city limits southward to include the old ’Ir David on the Ophel and Mount Sion.26

While she was ruling in Jerusalem, Eudokia became involved in the continuing doctrinal dispute about the person and nature of Christ. In 431 the Council of Ephesus had condemned the teachings of Nestorius, patriarch of Constantinople, who had declared that Jesus had two natures, human and divine: Mary had not been Theotokos, the God-Bearer, but only the mother of Jesus the man. After the council, Nestorius’s supporters in northern Syria founded their own breakaway church. Other Christians were unhappy with the official Nicene Orthodoxy for other reasons. Eutyches, an aged abbot of a monastery near Constantinople, went the other way, insisting that Jesus had only one nature (mone physis). It had been the divine Logos who had been born of the Virgin Mary and died on the cross. This offended the Orthodox, because the “Monophysites,” as they were called, seemed to have lost sight of Jesus’s humanity, which for them was apparently swallowed up by Christ’s overwhelming divinity. Many bishops and monks in Syria, Palestine, and Egypt espoused Monophysitism as a declaration of independence from Constantinople: they too formed separatist churches, represented in Jerusalem today by the Copts, Ethiopians, Armenians, and Syrian Jacobites. They were not simply supporting national independence, however, but were addressing the central religious question: how could the transcendent divinity establish a link with the world of human beings? In the old days, people had thought that temples established this connection with the sacred. Christians, however, had come to the astonishing conclusion that God had permanently allied himself to humanity in the person of Jesus, the god-man. The various Christological formulations were all stumbling attempts to see how this could have come to pass.

Eudokia, partly because of her quarrel with Pulcheria and the imperial family, supported the Monophysites in Jerusalem, as did Juvenal, the bishop of the city. He was rebuked by the bishop of Rome, Pope Leo the Great, who complained that it was outrageous that Juvenal, the custodian of the holy places, should teach a doctrine that virtually denied the humanity of Christ. As the successor of St. Peter, the chief disciple of Jesus, the bishop of Rome was widely regarded as the chief prelate in the church. Leo now put the weight of his authority behind the doctrine of the incarnation, writing an official “tome” which argued that the gospels constantly stressed the coexistence of humanity and divinity in Jesus. The holy places in Jerusalem, he claimed, were “unassailable proofs” that God had joined himself to the material world. For over a hundred years, Christians’ experience at these sacred sites had provided incontrovertible evidence that the physical objects with which the incarnate Logos had made contact had the power to introduce people to the sacred. They were an eloquent reminder of the physical reality of Jesus’s humanity. Leo’s Tome provided the text used at the new ecumenical council of the church which Pulcheria summoned to Chalcedon in Asia Minor in 451. At this council, Bishop Juvenal crossed the floor to join the Orthodox and was rewarded with the prize that had been sought by bishops of Jerusalem since the time of Makarios. The see of Jerusalem became a patriarchate that now took precedence over the sees of Caesarea, Beth Shan, and Petra.

When Eudokia and the Christians of Jerusalem heard of Juvenal’s defection, they not unnaturally felt betrayed, and they appointed Theodosius, a Monophysite, as their new bishop. Hordes of angry monks poured into Jerusalem from the Judaean monasteries, so that when Patriarch Juvenal arrived home with a guard of soldiers he was mobbed. He fled to the desert, where he lived in hiding in Rubra, to the west of Qumran. But the confusion of the church troubled Eudokia, and when Bishop Theodosius died in 457 she asked advice of the famous Syrian ascetic Simeon Stylites. He told her to consult Euthymius, the Armenian monastic leader, and Eudokia was so impressed by his teaching that she submitted to Orthodox doctrine. Anastasius, the Orthodox patriarch who had been appointed to replace Juvenal, took up residence in the new palace which Eudokia had built for him near the Anastasis. Her last project was to build a church and monastery for St. Stephen on the site of the modest shrine she had dedicated in 439. The bones of the martyr were carried there on 15 June 460, and four months later Eudokia herself died and was buried in the church.

Jerusalem was now a center of Nicene Orthodoxy, but the doctrinal conflict still raged in other churches, since many Eastern Christians regarded Chalcedon as an unworthy compromise. They also resented the doctrinal control exerted by the court. Future emperors, such as Zeno (474–91) and Anastasius (491–518), tried to appease these dissidents, fearing a split in the empire. Other groups also resented Byzantium. In 485 the Samaritans declared independence of Constantinople and crowned their own king: their revolt was cruelly put down by Emperor Zeno, who desecrated their place of sacrifice on Mount Gerizim, where he built a victory church in honor of Mary Theotokos.

The oppressive measures taken by the Christian emperors was beginning to alienate increasing numbers of their subjects, and this ultimately damaged the empire. The emperor Justinian (527–65), for example, was committed to Chalcedonian Orthodoxy. His efforts to suppress Monophysitism in some of the eastern provinces meant that whole sectors of the population were seriously disaffected. He also made it impossible for Jews to support the empire. Justinian’s Orthodoxy saw the destruction of Judaism as mandatory, and he published edicts that virtually deprived the Jewish faith of its status as religio licta in the imperial domains. Jews were forbidden to hold civil or military posts, even in such cities as Tiberias and Sepphoris where they were in a majority. The use of Hebrew was forbidden in the synagogues, and if Passover fell before Easter, Jews were not allowed to observe the festival on the correct date. Jews remained defiant. The Beth Alpha synagogue in Galilee, which may have been built at this time, could reflect a continued hope for the restoration of Jerusalem. The mosaic floor depicts the binding of Isaac, a tradition associated with the Temple Mount, and the cultic instruments used in the Temple, including the menorah and the palm branches and citrus fruits of Sukkoth, a festival which some Jews had come to associate with the Messiah.

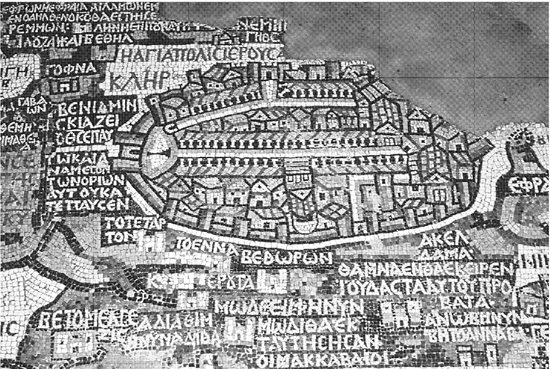

Part of Justinian’s offensive against dissident groups was his building program in and around Jerusalem. He restored Zeno’s victory church on Mount Gerizim and rebuilt Helena’s Nativity Basilica in Bethlehem, which had been badly damaged during the Samaritan revolt. His most impressive building in Jerusalem was the new Church of Mary Theotokos on the southern slope of the Western Hill. The church had been planned as a monument to Orthodoxy by the monk Sabas and Patriarch Elias during the reign of the Monophysite emperor Anastasius. The Nea, as the complex was known locally, was an impressive feat of engineering. Justinian had given very clear directions about its size and proportions, and since there was simply not enough room on the hill, the architects had to build huge vaults to support the church, monastery, and hospice with three thousand beds for the sick. The Nea was unique in Jerusalem, since it commemorated a doctrine and not an event in the life of Christ and the early church. It never quite won the hearts of the city’s Christians, and they made no move to restore it after its destruction in an earthquake of 746. It is, however, clearly visible on a mosaic map of Jerusalem during the reign of Justinian, which was discovered in a church at Madaba in present-day Jordan in 1884.

The Madaba mosaic map shows the two columned cardines and the western supporting wall of the city, as well as the Basilica of Holy Sion and Eudokia’s Church of Holy Wisdom28 in the supposed site of Pilate’s Praetorum. The map reflects the sacred geography of the Christian world which had developed since the time of Constantine. Palestine is depicted as the Holy Land: the map not only marks the biblical sites but also the new buildings, monuments, and monasteries by which the Christians had transformed the country into sacred space. Jerusalem, bearing the legend “The Holy City of Jerusalem,” is at the center of the map and had now been enshrined at the heart of the Christian world. Before the discovery of the tomb, Christians had been taught to discount the earthly city and concentrate on the heavenly Jerusalem. By the end of the fourth century, they had been fused in the Christian imagination, as we can see in the mosaic in the Church of St. Pudenziana in Rome, which shows Christ teaching his disciples in heaven: behind him Constantine’s new buildings at Golgotha are clearly visible. Jerusalem had thus become a holy Christian city, though not always a city of charity. All too often, the revelation of the city’s sacred character had been accompanied by internecine Christian struggles, power games, and the suppression of rival faiths.

When Justinian and Zeno wanted to make an emphatic statement about the power of Christian Orthodoxy, they had both built churches in honor of Mary Theotokos. The image of the Mother of God holding the infant Christ had become the rallying cry of Orthodoxy because it expressed the central paradox of the incarnation: it showed that the Logos had accepted the extreme vulnerability of infancy out of love for the world. The tenderness of the relationship between Mary and her son expressed God’s almost sensuous love for the human race:

Thou didst stretch out thy right arm, O Theotokos, thou didst take him and make him lie on thy left arm. Thou didst bend thy neck and let thy hair fall over him.… He stretched out his hand, he took thy breast, as he drew into his mouth the milk that is sweeter than manna.29

In a similar way, Christian pilgrims fondled and kissed the stones and wood that had once touched the incarnate Logos. This type of tactile spirituality shows how the incarnation and the Jerusalem cult could have enabled Christians to see sexual love as a means of transcendence, a development which, sadly, never came about in the Christian tradition. It is also tragic that this poignant vision of divine tenderness could not inspire Christians to a greater love and compassion for their fellow men. Unfortunately, the pathos of the Logos’s vulnerability does not seem to have helped some Christian inhabitants of Jerusalem to lay aside their own egotistic lust for power and control.

A fragment of the Madaba Mosaic Map, which precisely charts the main features of Christian Jerusalem at the time of Justinian. The two Cardines, built originally by Hadrian and clearly visible here, are still the main thoroughfares of the Old City.

Yet the physical approach to the spiritual gave many pilgrims a profound religious experience. It also made Jerusalem a natural center of Nicene Orthodoxy despite its earlier dalliance with Monophysitism. In 511 when Emperor Anastasius had been trying to impose a Monophysite patriarch upon the Jerusalem church, the monk Sabas had tried to explain that the experience of living in the holy city made it impossible for pilgrims and people to discount the humanity of Christ: “We, the inhabitants of Jerusalem, as it were, touch with our hands each day the truth through these holy places in which the mystery of our great God and Savior took place.”30 At some of the holy places Jesus was thought to have left a physical trace: he had literally impressed the stones indelibly with his presence. His footprint could be seen on the rock in the Ascension Church and on a stone in Eudokia’s Church of Holy Wisdom, where, it was said, Jesus had stood before Pilate.31 Theodosius, a Western pilgrim who visited Jerusalem in about 530, saw the print of Jesus’s body on the pillar on Mount Sion. He had

clung to it while he was being scourged, his hands, arms, and fingers sank into it, as if it were wax, and the marks appear to this day. Likewise his whole countenance, his chin, nose, and eyes, are impressed on it.32

Clinging to the stone, Jesus had in his extremity left a permanent impression of God’s perpetual embrace of humanity and the material world in his person. The earthly city of Jerusalem was now felt to be imbued with divine power, as a result of Jesus’s actions there. The very dew had healing properties, according to Antoninus, a pilgrim from Piacenza who visited Jerusalem in about 570. Christians bathed in the Pool of Siloam and the Pool of Beth-Hesda, the old site of the Asclepius cult, which had been replaced by a church in honor of the Virgin Mary’s nativity. Many cures were effected in these healing waters.33

The holy places were like the icons which were beginning to be seen as providing another link with the celestial world. The icon was not intended as a literal portrait of Jesus or the saints. Like any religious symbol, it was mysteriously one with the heavenly being it represented on earth. As the eighth-century monk Theodore of Studios remarked: “Every artificial image … exhibits in itself, by way of imitation, the form of its model.… the model [is] the image, the one in the other.”34 In rather the same way, the pilgrims who “imitated” Christ by following in his footsteps during the great processions around the city had become “living icons,” momentarily one with the Logos himself. So too, the holy places were not mere mementos but were experienced as earthly replicas of the divine. A pilgrim’s ampulla of this period shows the Rock of Golgotha, surmounted by a jeweled cross donated by Theodosius II, but the four rivers of Paradise are also depicted flowing from the rock. When they visited Golgotha, pilgrims were now shown the place where Adam had been created by God at the beginning of time. Golgotha was thought to be on the site of the Garden of Eden. It had become a symbol which gave pilgrims that experience of returning to Paradise which, as we have seen, has been such an important motif in the religious quest. Pilgrims did not visit Golgotha and the tomb as modern travelers visit a historical site: these earthly relics of Christ’s life on earth introduced them to a transcendence. This for a time assuaged that sense of separation and loss that lies at the root of so much human pain and gave them intimations of an integrity and wholeness which they felt to be their “real” state.

The creation of Christian Jerusalem had wholly shifted the sacred center of the city, which had formerly been Mount Zion and the Temple Mount. When the Bordeaux Pilgrim visited Jerusalem, he had started his tour there and then proceeded to the newer, Christian shrines. By the sixth century, Christians scarcely bothered to glance at the Temple platform. All the events that had once been thought to have occurred on Mount Zion were now located at Golgotha, the New Jerusalem. The Bordeaux Pilgrim had sited the murder of Zechariah at the Temple Mount and had seen the bloodstains on the pavement. Now pilgrims were shown the altar where Zechariah had been slain in Constantine’s Martyrium. The altar on which Abraham had bound Isaac and where Melchizedek had offered sacrifice—incidents formerly associated with Zion—were also displayed near Golgotha. There too was the horn which had contained the oil that had anointed David and Solomon, together with Solomon’s signet ring.35 This transition represented another Christian appropriation of Jewish tradition, but it also showed that the holiness of the New Jerusalem was so powerful that it pulled the tradition of the old Jerusalem into its orbit.

Yet the power of the holy city could not hold its earthly enemies at bay. The Byzantine empire was weak and internally divided, and its subjects were alienated from Constantinople. In 610, King Khosrow II of Persia judged the time right to invade Byzantine territory and began to dismember the empire. Antioch fell in 611, Damascus two years later, and in the spring of 614 the Persian general Shahrbaraz invaded Palestine, pillaging the countryside and burning its churches. The Jews of Palestine, who had happier memories of Persian than of Roman rule, came to their aid. On 15 April 614, the Persian army arrived outside the walls of Jerusalem. Patriarch Zacharias was ready to surrender the city but a group of young Christians refused to allow this, convinced that God would save them by a miracle. The siege lasted for nearly three weeks, while the Persians systematically destroyed all the churches and shrines outside the city, including St. Stephen’s church, the Eleona basilica, and the Ascension Church. At the end of May, Jerusalem fell amid scenes of horrific slaughter. In his eyewitness account, the monk Antiochus Strategos says that the Persians rushed into the city like wild boars, roaring, hissing, and killing everyone in sight: not even women and babies were spared. He estimated that 66,555 Christians died, and the city was vandalized, its churches, including the Martyrium, set aflame. Survivors were rounded up, and those who were skilled or of high rank were taken into exile, including Patriarch Zacharias.

When the deportees reached the summit of the Mount of Olives and looked back on the burning city, they began to weep, beat their breasts, and pour dust over their heads, like the Jews whose mourning rituals they had so thoroughly despised. When Zacharias sought to calm them, he uttered a lament for the Christian Holy City which had now become inseparable from the idea and experience of God:

O Zion, do not forget me, your servant, and may your Creator not forget you. For if I forget you, O Jerusalem, let my right hand wither. Let my tongue cleave to the roof of my mouth if I do not remember you.… I adore you, O Zion, and I adore him who dwelled in you.36

The Christians had sharply differentiated their experience in Jerusalem from that of the Jews. Now as they went into exile in their turn, they turned naturally to the gestures and psalms of their predecessors in the Holy City, and like the Jews they spoke of God and Zion in the same breath. With the exiles went the relic of the True Cross together with other implements of the Passion of Christ that had been kept in the Martyrium: the spear that had pierced his side, the sponge and the onyx cup that he was supposed to have used at the Last Supper. They passed into the possession of Queen Meryam of Persia, who was a Nestorian Christian.

When they left Jerusalem to continue their campaign, the Persians left the city in the charge of the Jews, their allies in Palestine. Messianic hopes soared: visionaries looked forward to the imminent purification of the land by the Messiah and to the rebuilding of the Temple. Some contemporaries even hint that sacrifice was resumed on the Mount during this period, that booths were built once again during Sukkoth and that prayers were recited at the ruined city gates.37 But in 616, when the Persians returned to Palestine, they took over control of the city. They had now realized that if they were to pacify the country, they had to make some concessions to the Christian majority. Withdrawal of Persian support spelled the end of any realistic hope for the restoration of Jerusalem to the Jewish nation.

In 622, Heraklius, Emperor of Byzantium, resumed the offensive against Persia, campaigning for six years in Persian territory until he arrived outside Ctesiphon, where Khosrow II was assassinated in a palace coup. Persia and Byzantium made peace and both powers evacuated each other’s territory, but they were both exhausted by the long years of destructive warfare and would never truly recover. Nevertheless, the Christians of Jerusalem were jubilant. On 21 March 629, Heraklius entered Jerusalem in a splendid procession, carrying the relic of the True Cross. The “Golden Gate” in the eastern supporting wall of the Temple Mount may have been built in honor of his triumphal entrance. The emperor marched through the city streets to the Anastasis and returned the cross to its rightful home. Both the Martyrium and the Rotunda shrine around the tomb had been damaged in 614, but the buildings were still standing. Modestos, a monk of the Judaean desert, had taken charge of the repairs, and since Zacharias had died in exile, Heraklius appointed Modestos patriarch of Jerusalem in recognition of his services. Heraklius had issued an official pardon to the Jews for their collaboration with Persia but found that he had to make some gestures to appease the Christians. A new edict banned the Jews from Jerusalem yet again; some Jews accused of killing Christians or burning churches during Persian rule were executed, while others fled to Persia, Egypt, or the desert. Those who remained in Galilee were forbidden to recite the Sh’ma in public or to hold services in the synagogue more than once a week. In 634, Heraklius commanded all the Jews of his empire to be baptized. Yet again a Christian emperor had totally alienated his Jewish subjects, and Heraklius would find it impossible to gain their support three years later, when the empire was again in deadly peril.

The Christians were exultant. Yet again, as after the reign of the apostate Julian, their Holy City had been restored to them. This time they would never let it go. The fervent Orthodox monk Sophronius, who became patriarch of Jerusalem in 633, wrote two poems describing his love of the city. He imagined himself running from one place to another, kissing the stones and weeping over the sites of the Passion. For Sophronius the tomb represented the earthly paradise:

O light-giving Tomb, thou art the ocean stream of eternal life and the true river of Lethe. I would lie at full length and kiss that stone, the sacred center of the world, wherein the tree was fixed which did away with the curse of [Adam’s] tree.… Hail to thee, Zion, splendid sun of the world, for whom I long and groan by day and by night.38

The experience of living in Jerusalem had impelled the Christians to develop a full-blown sacred geography, based on the kind of mythology they had once despised. They now saw Jerusalem as the center of the world, the source of life, fertility, salvation, and enlightenment. Now that they had died in such great numbers for their city, it was dearer to them than ever. The restoration of Jerusalem to the Christian emperor seemed an act of God. But in 632, the year before Sophronius became patriarch, a prophet who had followed the recent developments in Jerusalem with interest died in the Arabian settlement of Yathrib. Five years later, an army of his friends and followers arrived outside the walls of Jerusalem.