THE HOLOCAUST that so many of the Israelis had feared in 1967 never, of course, came to pass. On 5 June, the Israeli forces launched a preemptive strike against the United Arab Republic and destroyed almost the entire Egyptian air force on the ground. This inevitably drew Jordan into the war, though Jerusalem was inadequately defended by, perhaps, as few as five thousand troops. They did their best—two hundred died in the defense of the Holy City—but on Wednesday, 7 June, the Israel Defense Forces circled the Old City and entered it through the Lion Gate. Most Israeli civilians were still in their air-raid shelters, but news of the capture of Arab Jerusalem spread by word of mouth and a wondering crowd gathered at the Mandelbaum Gate.

Meanwhile, Israeli soldiers and officers had one objective: to get as quickly as possible to the Western Wall. The men ran through the narrow winding streets and rushed over the Ḥaram platform, scarcely giving the Muslim shrines a glance. It was not long before seven hundred soldiers with blackened faces and bloodstained uniforms had crowded into the small enclave that had been closed to Jews for almost twenty years. By 11:00 a.m., the generals began to arrive, bringing General Shlomo Goren, chief rabbi of the IDF, who had the honor of blowing the shofar at the wall for the first time since 1929. A platoon commander also sent a jeep to bring Rabbi Zvi Yehuda Kook to the wall. For all these men, whatever their theological beliefs, confronting the wall was a profound—even shocking—religious experience. Only a few days earlier they had faced the possibility of annihilation. Now they had unexpectedly made contact once again with what had become the most holy place in the Jewish world. Secular young paratroopers clung to the stones and wept: others were in shock, finding it impossible to move. When Rabbi Goren blew the shofar and began to intone the psalms, atheistic officers embraced one another, and one young soldier recalled that he became dizzy; his whole body burned. It was a dramatic and unlooked-for return that seemed an almost uncanny repetition of the old Jewish myths. Once again the Jewish people had struggled through the threat of extinction; once again they had come home. The event evoked all the usual experiences of sacred space. The wall was not merely a historical site but a symbol that reached right down to the core of each soldier’s Jewish identity. It was both Other—“something big and terrible and from another world”1—and profoundly familiar—“an old friend, impossible to mistake.”2 It was terrible but fascinans; holy, and at the same time a mirror image of the Jewish self. It stood for survival, for continuity, and promised that final reconciliation for which humanity yearns. When he kissed the stones, Avraham Davdevani felt that past, present, and future had come together: “There will be no more destruction and the wall will never again be deserted.”3 It presaged an end to violence, dereliction, and separation. It was what other generations might have called a return to paradise.

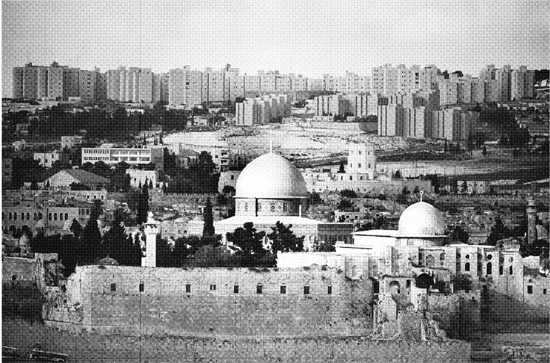

“This is how the conquering generation looks.” Exultant Jewish soldiers pose before the Dome of the Rock after their conquest of the Old City in 1967.

Religious Jews, especially the disciples of Rabbi Kook the Younger, were convinced that the Redemption had begun. They recalled their rabbi’s words only a few weeks earlier and became convinced that he had been divinely inspired. Standing before the wall on the day of the conquest, Rabbi Kook announced that “under heavenly command” the Jewish people “have just returned home in the elevations of holiness and our own holy city.”4 One of his students, Israel “Ariel” Stitieglitz, left the wall and walked on the Ḥaram platform, heedless of the purity laws and the forbidden areas, bloodstained and dirty as he was. “I stood there in the place where the High Priest would enter once a year, barefoot, after five plunges in the mikveh,” he remembered later. “But I was shod, armed, and helmeted. And I said to myself, This is how the conquering generation looks.’ ”5 The last battle had been fought, and Israel was now a nation of priests; all Jews could enter the Holy of Holies. The whole Israeli army, as Rabbi Kook repeatedly pointed out, was “holy” and its soldiers could step forward boldly into the Presence of God.6

The phrase “Never again!” now sprang instantly to Jewish lips in connection with the Nazi Holocaust. This tragedy had become inextricably fused with the identity of the new state. Many Jews saw the State of Israel as an attempt to create new life in the face of that darkness. Memories of the Holocaust had inevitably surfaced in the weeks before the Six-Day War, as Israelis listened to Nasser’s rhetoric of hatred. Now that they had returned to the Western Wall, the words “Never again!” were immediately heard in this new context. “We shall never move out of here,”7 Rabbi Kook had announced, hours after the victory. General Moshe Dayan, an avowed secularist, stood before the wall and proclaimed that the divided city of Jerusalem had been “reunited” by the IDF. “We have returned to our most holy places; we have returned and we shall never leave them.”8 He gave orders that all the city gates be opened and the barbed wire and mines of No Man’s Land be removed. There could be no going back.

Israel’s claim to the city was dubious. At the end of the Six-Day War, Israel had occupied not only Jerusalem but the West Bank, the Gaza Strip, the Sinai Peninsula, and the Golan Heights. (See map.) Neither the Hague Regulations of 1907 nor the Geneva Conventions of 1949 supported Israel’s claim. It was no longer permissible in international law permanently to annex land conquered militarily. Some Israelis, including Prime Minister Levi Eshkol, were willing to give back these Occupied Territories to Syria, Egypt, and Jordan in return for peace with the Arab world. But there was never any question in 1967 of returning the Old City of Jerusalem to the Arabs. With the conquest of the Western Wall, a transcendent element had entered Zionist discourse, once so defiantly secular. Even the most diehard atheists had experienced their Holy City as “sacred.” As Abba Eban, Israel’s delegate to the United Nations, expressed it, Jerusalem “lies beyond and above, before and after, all political and secular considerations.”9 It was impossible for Israelis to see the matter objectively, since at the wall they had encountered the Jewish soul.

On the evening of the conquest, Levi Eshkol announced that Jerusalem was “the eternal capital of Israel.”10 The conquest of the city had been such a profound experience that, to many Jewish people, it seemed essentially “right”: it was a startling evocation of myths and legends that had nurtured Jews for centuries in the countries of the Diaspora. As Kabbalists would put it, now that Israel was back in Zion, everything in the world and the entire cosmos had fallen back into its proper place. The Arabs of Jerusalem could scarcely share this view of the matter, however.11 The Israeli conquest was not a “reunification” of the city but its occupation by a hostile power. The bodies of about two hundred soldiers of the Arab Legion lay in the streets; Arab civilians had been killed. Israeli reserve units were searching the houses for weapons and arrested several hundred Palestinians whose names were on a prepared wanted list. The men were marched away from their families, convinced they were going to their deaths. When they were allowed to return that evening, they were greeted with tears as though they had escaped from Hades. Looters had followed behind the troops: some of the mosques had been robbed and the Dead Sea Scrolls had been removed from the Palestine Archaeological Museum. The Palestinian inhabitants of the Old City and East Jerusalem locked themselves fearfully in their houses until Mayor Rauhi al-Khatib walked through the streets with an Israeli officer persuading them to come out and reopen the shops so that people could buy food. On the morning of Friday, 9 June, half the Arab municipal workers reported for duty, and, under the direction of the mayor and his deputy, they began to bury the dead and repair the water systems. They were later joined by Israeli municipal workers in East Jerusalem.

But this cooperation did not last. On the very day of the conquest, Teddy Kollek approached Dayan and promised that he would personally supervise the clearing of No Man’s Land, a task of great danger and complexity. Like Dayan, he saw the importance of “creating facts” that would establish a permanent Jewish presence in the Holy City, so that there could be no question of vacating it at the behest of the international community. On the night of Saturday, TO June, after the armistice had been signed, the 619 inhabitants of the Maghribi Quarter were given three hours to evacuate their homes. Then the bulldozers came in and reduced this historic district—one of the earliest of the Jerusalem awqāf—to rubble. This act, which contravened the Geneva Conventions, was supervised by Kollek in order to create a plaza big enough to accommodate the thousands of Jewish pilgrims who were expected to flock to the Western Wall. This was only the first act in a long and continuing process of “urban renewal”—a renewal based on the dismantling of historic Arab Jerusalem—that would entirely transform the appearance and character of the city.

On 28 June, the Israeli Knesset formally annexed the Old City and East Jerusalem, declaring them to be part of the State of Israel. This directly contravened the Hague Convention, and there had already been demands from the Arab countries, the Soviet Union, and the Communist bloc for Israel to withdraw from occupied Arab Jerusalem. Britain had told the Israelis not to regard their conquest of the city as permanent. Even the United States, always kindly disposed toward Israel, had warned against any formal legislation to change the status of the city, since it could have no standing in international law. The Knesset’s new Law and Administration Ordinance of 28 June carefully avoided using the word “annexation.” Israelis preferred the more positive term “unification.” At the same time, the Knesset enlarged the boundaries of municipal Jerusalem, so that the city now covered a much wider area. The new borders skillfully zigzagged around areas that had a large Arab population and included plenty of vacant land for new Israeli settlements. (See map.) This ensured that the voting population of the city would remain predominantly Jewish. Finally, on the day after the annexation, Mayor al-Khatib and his council were dismissed in an insulting ceremony. They were driven by the military police from their homes to the Gloria Hotel near the Municipality Building. There Yaakov Salman, the deputy military governor, read a prepared statement that curtly informed the mayor and his council that their services were no longer required. When al-Khatib asked to have the statement in writing, Salman’s assistant, David Farhi, scribbled the Arabic translation on a paper napkin belonging to the hotel.12 The ceremony had been designed to bid a formal farewell to the mayor, who had cooperated so generously with the Israelis, and to explain the new legal status of Jerusalem to him in person. But this was not done. The bitterness of the former mayor and councillors was not due to their dismissal: that, they knew, was inevitable. What offended them was the humiliating and undignified form of the ceremony, which did not reflect the importance of the occasion. Some members of the Israeli government had thought that the Arab municipality should continue in some form to work side by side with—or under—the municipality of West Jerusalem. Teddy Kollek would have none of this. The Arabs, he said, would “get in the way of my work.” “Jerusalem is one city,” he told the press, “and it will have one municipality.”13

At midday on 29 June, the barriers dividing the city came down and Arabs and Israelis crossed No Man’s Land and visited the “other side.” The Israelis, the conquerors, rushed exuberantly into the Old City, buying everything in sight in the sūq, shocked to find that the Arabs had been enjoying luxury food and foreign imports that had been unavailable in West Jerusalem. The Arabs were more hesitant. Some took the keys of their old houses in Katamon and Bak a, which they had kept in the family since 1948, and stood staring at their former homes. Some Jews were embarrassed when Arabs knocked at the door and politely asked permission to look inside their family houses. Yet there was no violence, and at the end of the day the Israelis generally believed that the Arabs were beginning to accept the “reunification” of the city. In fact, as events would prove, they were simply in shock. There was no such acceptance. Al-Quds was a holy place to the Arabs too. The Palestinians had suffered their own annihilation in 1948, and now they were beginning to be eliminated from Jerusalem as well. Their former mayor, Rauhi al-Khatib, calculated that by 1967 there were about 106,000 Arab Jerusalemites in exile as a result of the wars with Israel.14 Now, because of the new gerrymandered boundaries, Arabs would account for only about 25 percent of the city’s population. Palestinians were suffering their own exile, homelessness, and separation. They could not share the Kabbalistic dream: as far as they were concerned, everything was in the wrong place. This experience of dislocation and loss would make Jerusalem more precious than ever to the Arabs.

a, which they had kept in the family since 1948, and stood staring at their former homes. Some Jews were embarrassed when Arabs knocked at the door and politely asked permission to look inside their family houses. Yet there was no violence, and at the end of the day the Israelis generally believed that the Arabs were beginning to accept the “reunification” of the city. In fact, as events would prove, they were simply in shock. There was no such acceptance. Al-Quds was a holy place to the Arabs too. The Palestinians had suffered their own annihilation in 1948, and now they were beginning to be eliminated from Jerusalem as well. Their former mayor, Rauhi al-Khatib, calculated that by 1967 there were about 106,000 Arab Jerusalemites in exile as a result of the wars with Israel.14 Now, because of the new gerrymandered boundaries, Arabs would account for only about 25 percent of the city’s population. Palestinians were suffering their own exile, homelessness, and separation. They could not share the Kabbalistic dream: as far as they were concerned, everything was in the wrong place. This experience of dislocation and loss would make Jerusalem more precious than ever to the Arabs.

The international community was also unwilling to accept Israel’s annexation of Jerusalem. In July 1967, the United Nations passed two resolutions calling upon Israel to rescind this “unification” and to desist from any action that would alter the status of Jerusalem. The war and its aftermath had at last drawn the attention of the world to the plight of the dispossessed Palestinian refugees; now thousands more had fled Israel’s Occupied Territories and languished in the camps in the surrounding Arab countries. Finally, on 22 November 1967, the United Nations Security Council passed Resolution 242: Israel must withdraw from the territories it had occupied during the Six-Day War. The sovereignty, territorial integrity, and political independence of all the states in the region must be acknowledged.

But most of the Israelis and many Jews in the Diaspora had been caught up in their new passion for sacred space and could not recognize the validity of these resolutions. Since the destruction of the Temple, Jews had gradually relinquished the notion of physically occupying Jerusalem. The sacred geography had been internalized, and many of the Orthodox still regarded the State of Israel as an impious human creation. But the dramatic events of 7 June were beginning to change this. The situation was not unlike the transformation of the Christian idea of Jerusalem in the time of Constantine. Like the Jews, the Christians had thought that they had outgrown the devotion to holy places, but the unexpected reunion with the tomb of Christ had almost immediately led to a new appreciation of Jerusalem as a sacred symbol. Like the Jews, the Christians of the fourth century had recently emerged from a period of savage persecution. Like the Jews again, they had just acquired an entirely new political standing in the world. The Nazi catastrophe had inflicted a wound that was too deep to be healed by more cerebral consolations. The old myths—an ancient form of psychology—could reach to a deeper, less rationally articulate level of the soul. This new Jewish passion for the holiness of Jerusalem could not be gainsaid by mere United Nations directives nor by logically discursive arguments. It was powerful not because it was legal or reasonable but precisely because it was a myth.

In Constantine’s time, the tomb of Christ had been discovered during one of the first-recorded archaeological excavations in history. The process of digging down beneath the surface to a buried and hitherto inaccessible sanctity was itself a powerful symbol of the quest for psychic healing. Fourth-century Christians, no longer a persecuted, helpless minority, were having to reevaluate their religion and find a source of strength as they struggled—often painfully—to build a fresh Christian identity. Freud had been quick to see the connection between archaeology and psychoanalysis. In Israel too, as the Israeli writer Amos Elon has so perceptively shown, archaeology became a quasi-religious passion. Like farming, it was a way for the settlers to reacquaint themselves with the Land. When they found physical evidence in the ground of Jewish life in Palestine in previous times, they gained a new faith in their right to the country. It helped to still their doubts about their Palestinian predecessors. As Moshe Dayan, the most famous of Israel’s amateur archaeologists, remarked in an interview, Israelis discovered their “religious values” in archaeology. “They learn that their forefathers were in this country three thousand years ago. This is a value.… By this they fight and by this they live.”15 In this pursuit of patriotic archaeology, Elon argues, “it is possible to observe, as of faith or of Freudian analysis, the achievement of a kind of cure; men overcome their doubts and fears and feel rejuvenated through the exposure of real, or assumed, but always hidden origins.”16

The exhibition hall built to house the Dead Sea Scrolls, which had been captured during the Six-Day War, shows how thoroughly the Israelis had adapted the old symbols of sacred geography to their own needs. Its white dome has become one of the most famous landmarks of Jewish Jerusalem, and, facing the Knesset, it challenges the Christian and Muslim domes that have in the past been built to embody rival claims to the Holy City. As Elon points out, Israelis tend to regard the scrolls as deeds of possession of this contested country. Their discovery in 1947, almost coinciding with the birth of the Jewish state, seemed perfectly timed to demonstrate the prior existence of Israel in Palestine. The building is known as the Shrine of the Book, a title that draws attention to its sacred significance. The womblike interior of the shrine, entered through a dark, narrow tunnel, is a graphic symbol of the return to the primal peace and harmony which, in the secular society of the twentieth century, has often been associated with the prenatal experience. The phallic, clublike sculpture in the center of the shrine demonstrates the national will to survive—but also, perhaps, the mating of male and female elements that has frequently characterized life in the lost paradise. The holy place had long been seen as a source of fertility, and in the shrine, says Elon, “archaeology and nationalism are united as in an ancient and rejuvenative fertility rite.”17

But, like the fierce theology of Qumran, this quest for healing and national identity had an aggressive edge. From the first, Moshe Dayan made it clear that Israel would respect the rights of Christians and Muslims to run their own shrines. Israelis would proudly compare their behavior with that of the Jordanians, who had denied Jews access to the Western Wall. On the day after the conquest, the military governor of the West Bank held a meeting to reassure all the Christian sects of Jerusalem, and on 17 June, Dayan told the Muslims that they would continue to control the Ḥaram. He made Rabbi Goren remove the Ark that he had placed on the southern end of the platform. Jews were forbidden by the Israeli government to pray or hold services on the Ḥaram, since it was now a Muslim holy place. The Israeli government has never retreated from this policy, which shows that the Zionist conquerors were not entirely without respect for the sacred rights of their predecessors in Jerusalem. But Dayan’s decision immediately enraged some Israelis. A group calling itself the Temple Mount Faithful was formed in Jerusalem. They were not especially religious. Gershom Solomon, one of their leaders, was a member of Begin’s right-wing Herut party and was moved more by nationalist than by religious aspirations. He argued that Dayan had no right to prohibit Jewish prayers on the Temple Mount, since the Holy Places Bill guaranteed freedom of access to all worshippers. On the contrary, since the Temple Mount had been the political as well as the religious center of ancient Israel, the Knesset, the President’s Residence, and government offices should move to the Ḥaram.18 On the major Jewish festivals, the Temple Mount Faithful have continued to pray on the Ḥaram and are regularly ejected by the police. A similar mechanism had inspired the demolition of the Maghribi Quarter: in the eyes of Israel’s right, the Jews’ return to their holy place involved the destruction of the Muslim presence there.

This became clear in August 1967, when Rabbi Goren and some yeshiva students marched onto the Ḥaram on the Ninth of Av and, after fighting off the Muslim guards and the Israeli police, held a service which ended with Rabbi Goren blowing the shofar. Prayer had become a weapon in a holy war against Islam. Dayan tried to reassure the Muslims and closed down the rabbinate offices that Goren had established in one of the Mamluk madāris. Just as the agitation was subsiding, however, Zerah Wahrhaftig, minister for religious affairs, published an interview in which he claimed that the Temple Mount had belonged to Israel ever since David had purchased the site from Araunah the Jebusite;19 Israel had, therefore, a legal right to demolish the Dome of the Rock and the Aqsā Mosque. The minister, however, did not actually recommend this course of action, since Jewish law stated that only the Messiah would be permitted to build the Third Temple. (It will be recalled that, even though any such new shrine would technically be the fourth Jewish temple, the services had never been interrupted during the construction of Herod’s building, so that it too was known as the Second Temple.)

On the day of the conquest, it had seemed to the soldiers who had crowded up to kiss the Western Wall that a new era of peace and harmony had begun. But in fact Zion, the city of peace, was once again the scene of hatred and discord. Not only had the return to the Jewish holy places led to a new conflict with Islam, it had also revealed the deep fissures within Israeli society. Almost immediately the new plaza created by the destruction of the Maghribi Quarter became the source of a fresh Jewish quarrel. Kollek’s hasty action appeared to have been not only inhumane but an aesthetic mistake. The confined space of the old narrow enclave had made the Western Wall look bigger than it was. Now it appeared little higher than the walls of the adjoining Tanziqiyya Madrasah or Suleiman’s city wall, which were now clearly visible. “Its gigantic stones seemed to have shrunk, their size diminished,” a disappointed visitor remarked on the day of the opening. The wall at first glance seemed to be “fusing with the stones of the houses to the left.” The intimacy of the narrow enclave had gone. The new plaza no longer “permitted the psychic affinity and the feeling that whoever comes here is, as it were, alone with his Maker.”20

Soon a most unholy row had erupted between the religious and the secular Jews about the management and conduct of the site.21 The wall was now a tourist attraction and visitors no longer came solely to pray. The ministry for religious affairs, therefore, wanted to fence off a new praying area directly in front of the wall. Secular Israelis were furious: how dare the ministry deny other Jews access to the wall? They were as bad as the Jordanians! Soon the rabbis were also in bitter conflict about the actual extent of this holy space. Some argued that the whole of the Western Wall was sacred, as well as the plaza in front of it. They started excavating the basements of the Tanziqiyya Madrasah, establishing a synagogue in one of the underground chambers and declaring every cellar or vault they cleared to be a holy place. Naturally Muslims feared that this religious archaeology was radically—and literally—undermining their own sacred precincts. But the rabbis were also trying to liberate Jerusalem from the Jewish secularists, pushing forward the frontiers of sanctity into the godless realm of the municipality. This struggle intensified when the Israeli archaeologist Benjamin Mazar started to excavate the southern end of the Ḥaram. This again alarmed the Muslims, who were afraid that he would damage the foundations of the Aqsā Mosque. Religious Jews were also enraged at this unholy penetration of sacred space, especially when Mazar edged around the foot of the Western Wall and inched his way up to Robinson’s Arch. Within a few months of the “unification” of the city, there was a new “partition” at the Western Wall. The southern end was now a historic, “secular” zone; the old praying area was the domain of the religious; and in between was a neutral zone—a new No Man’s Land—which consisted of a few remaining Arab houses. Once these had been demolished, each side looked covetously at the space between them. On two occasions in the summer of 1969, the worshippers actually charged through the barbed-wire fence in order to liberate this neutral area for God.

The Israeli government attempted to keep the peace at the holy places but was fighting its own war for the possession of Jerusalem, resorting to the time-honored weapon of building.22 Almost immediately, the Israelis began to plan new “facts” to bring more Jews into Jerusalem by constructing a security zone of high-rise apartment blocks around East Jerusalem. These were built at French Hill, Ramat Eshkol, Ramot, East Talpiot, Neve Yakov, and Gilo. (See map.) Several miles farther east, on the hills leading down to the Jordan Valley, an outer security belt was constructed at Ma’alot Adumin. Building proceeded at frantic speed, mostly on expropriated Arab land. Strategic roads linked one settlement to another. The result was not only an aesthetic disaster—the skyline of Jerusalem having been spoiled by these ugly blocks—but an effective destruction of long-established Arab districts. During the first ten years after the annexation, the Israeli government is estimated to have seized some 37,065 acres from the Arabs. It was an act of conquest and destruction. Today only 13.5 percent of East Jerusalem remains in Arab hands.23 The city had indeed been “united,” since there was no longer a clear distinction between Jewish and Arab Jerusalem, but this was not the united Zion for which the prophets had longed. As the Israeli geographers Michael Romann and Alex Weingrod have remarked, the militaristic terminology of the planners, when they speak of “engulfing,” “breaching,” “penetration,” “territorial domination,” and “control,” reveals their aggressive intentions toward the Arab population in the city.24

As they found themselves being squeezed out of al-Quds, the Arabs had to organize their own defense, and though they could do nothing to counter this building offensive, they managed to wrest some significant concessions from the government. In July 1967, for example, they refused to accept the qā˙ īs’ law which had been imposed on the Muslim officials in Israel proper. Nor would the qā˙

īs’ law which had been imposed on the Muslim officials in Israel proper. Nor would the qā˙ īs of Jerusalem change their rulings to fit Israeli law on such matters as marriage, divorce, the waqf, and the status of women. On 24 July 1967 the

īs of Jerusalem change their rulings to fit Israeli law on such matters as marriage, divorce, the waqf, and the status of women. On 24 July 1967 the  ulamā

ulamā announced that they were going to revive the Supreme Muslim Council, since it was against Islamic law for unbelievers to control Muslim religious affairs. The government responded by expelling some of its more radical Muslim opponents but in the end was forced to recognize, if only tacitly, the existence of the Supreme Muslim Council. Arabs also fought an effective campaign against the imposition of the Israeli educational system in Jerusalem, since it did not do justice to their own national aspirations, language, and history. Only thirty hours a year were devoted to the Qur

announced that they were going to revive the Supreme Muslim Council, since it was against Islamic law for unbelievers to control Muslim religious affairs. The government responded by expelling some of its more radical Muslim opponents but in the end was forced to recognize, if only tacitly, the existence of the Supreme Muslim Council. Arabs also fought an effective campaign against the imposition of the Israeli educational system in Jerusalem, since it did not do justice to their own national aspirations, language, and history. Only thirty hours a year were devoted to the Qur ān, for example, compared with 156 hours of Bible, Mishnah, and Haggadah. Students who matriculated from these Israeli schools would not be eligible to study at Arab universities. Eventually the government had to compromise and allow a parallel Jordanian curriculum in the city.

ān, for example, compared with 156 hours of Bible, Mishnah, and Haggadah. Students who matriculated from these Israeli schools would not be eligible to study at Arab universities. Eventually the government had to compromise and allow a parallel Jordanian curriculum in the city.

The Israelis were discovering that the Arabs of Jerusalem were not as malleable as the Arabs in Israel proper. In August they began a campaign of civil disobedience, calling for a general strike: on 7 August 1967 all shops, businesses, and restaurants closed for the day. Worse, extremist members of Yasir Arafat’s Fatah established cells in the city and began a terror campaign. On 8 October three of these cells tried to blow up the Zion Cinema. On 22 November 1968, the anniversary of UN Resolution 202, a car bomb in the Ma˙hane Yehudah market killed twelve people and injured fifty-four. In February and March 1969 there were more bomb attacks: one in the cafeteria of the National Library of the Hebrew University injured twenty-six people and did a great deal of damage. West Jerusalem suffered more terrorist attacks than any other city in Israel, and, perhaps inevitably, these led to Jewish reprisals. On 18 August 1968 when demolition charges exploded at several points in the city center, hundreds of young Jewish men burst into Arab neighborhoods, smashing shop windows and beating up Arabs they encountered on the streets.

The Israeli public was shocked by this anti-Arab pogrom. They were also dismayed by the depth of Arab hatred and suspicion that erupted on 21 August 1969 when a fire broke out in the Aqsā Mosque, destroying the famous pulpit of Nūr ad-Dīn and licking up the large wooden beams supporting the ceiling. Hundreds of Muslims rushed to the mosque, weeping and flinging themselves into the burning building. They screamed abuse at the Israeli firefighters, accusing them of spraying gasoline on the flames. Throughout the city, Arabs demonstrated and clashed with the police. Given the inflammatory behavior of some Israelis in the Ḥaram, it is hardly surprising that the Muslims immediately assumed that the arsonist had been a Zionist. Yet it had in fact been a disturbed young Christian tourist, David Rohan of Australia, who had set fire to the mosque in the hope that it would hasten Christ’s Second Coming. It took months before the government was able to allay Muslim fears and assure them that Rohan was indeed a Christian and not a Jewish agent and that Jews had no plans to destroy the shrines on the Ḥaram.

By 1974 the new Jewish settlements dominated the Jerusalem skyline, surrounding the city like the old Crusader castles. Once again, Jerusalem had become a fortress city, holding antagonistic neighbors at bay.

Yet during the next four years a sullen calm descended on Jerusalem. There were even signs that Israelis and Arabs were beginning to learn how to live with one another. After the death of Nasser in September 1970, the government gave permission for the Arabs of Jerusalem to hold a mourning procession for this enemy of the State of Israel. On Thursday, 1 October, the whole Arab population of the city assembled quietly and marched to the Ḥaram in perfect order. As agreed, there were no Israeli policemen on the streets, nor was there a single anti-Israeli placard in sight. Yet the Palestinians had not given up during these years of peace, as some Israelis hoped. They had adopted the policy of sumud (“steadfastness”), realizing that their physical presence in the city was their chief weapon. They would take advantage of the welfare and economic benefits that Israel was so keen to thrust upon them; they would continue to live in Jerusalem and beget children there. “We shall not give you the excuse to throw us out,” one of the Palestinian leaders said. “By the mere fact of being there, we shall remind you every day that the problem of Jerusalem has got to be solved.”25

In October 1973, Egypt and Syria launched a surprise attack on Israel on Yom Kippur, which changed the mood on both sides. This time the Arabs did much better, and, caught off guard, it took the IDF days to repel the attack. In Jerusalem the morale of the Palestinians improved, and they began to hope that the Israeli annexation of al-Quds might only be temporary. The Israelis had been shocked out of their complacency by this new revelation of their isolation in the Near East. This fear led to a new intransigence in Israel, especially among religious groups. Shortly after the war, disciples of Rabbi Kook founded the Gush Emunim (“Bloc of the Faithful”).26 Their love affair with the Israeli establishment was over: God had offered Israel a magnificent opportunity in 1967, but instead of colonizing the occupied territories and defying the international community, the government had merely tried to appease the goyim. The Yom Kippur War had been God’s punishment and a salutary reminder. Secular Zionism was dead: instead, the Gush offered a Zionism of Redemption and Torah. After the war, its members began to establish settlements in the occupied territories, convinced that this holy colonization would hasten the coming of the Messiah. The chief focus of Gush activity was not Jerusalem, however, but Hebron, where Rabbi Moshe Levinger, one of the founding members, managed by skillful lobbying to get the Israeli government to found a new town at Kiryat Arba next to Hebron. There the settlers began to agitate for more prayer time in the Cave of the Patriarchs, where Jews were allowed to worship only at certain times. But Levinger was also determined to establish a Jewish base in the city of Hebron itself and to avenge the massacre of Jews there during the riots of 1929. Soon the place where Abraham was said to have genially encountered his God in human form would become the most violent and hate-ridden city in Israel.

When Menachem Begin’s new Likud party ousted the Labor government and came to power in 1977, the hopes of the right soared, especially when the new government called for massive settlement on the West Bank. But then, to their horror, Begin, of all people, began to make peace with the Arab world. On 20 December, President Anwar al-Sadat of Egypt made his historic visit to Jerusalem, and the following year, he and Begin signed the Camp David Accords. Egypt recognized the State of Israel, and in return, Begin promised to withdraw from the Sinai Peninsula. This drew him into outright confrontation with the Israeli settlers, who had built the Jewish town of Yamit in the Sinai and fought to the last in an attempt to prevent its dismantling. New right-wing groups were formed to oppose the accords and to fight against the government.

In Jerusalem the new far-right activities centered increasingly on the Temple Mount. In 1978, Rabbi Shlomo Aviner founded the Yeshivat Ateret ha-Kohanim (“Crown of the Priests Yeshiva”), as an annex of Rabbi Kook’s Merkaz Harav. One of its objectives was to Judaize the Old City. After the 1967 conquest, the government had restored the old Jewish Quarter, which, during the Jordanian period, had been a refugee camp. The desecrated synagogues were restored, the old damaged houses pulled down, and new houses, shops, and galleries built. In the eyes of the Ateret ha-Kohanim, this was not enough. Funded largely by American Jews, the yeshiva began to buy Arab property in the Muslim Quarter, and within ten years it owned more than seventy buildings.27

The chief work of the new yeshiva, however, was to study the religious meaning of the Temple.28 Rabbi Aviner himself did not believe that Jews should build the Third Temple, a task reserved for the Messiah, but his deputy Rabbi Menachem Fruman wanted his students to be ready to undertake the Temple avodah when the Messiah did arrive—an eventuality he expected in the near future. He began to research the rules and techniques of sacrifice and instructed his students in this lore. Rabbi David Elboim began to weave the priests’ vestments, following the minute—and frequently obscure—directions of the Torah.

Others believed that more decisive action was necessary. Shortly after Sadat’s visit to Jerusalem, two Gush members, Yehuda Etzion and Menachem Livni, began to hold secret meetings with a Jerusalem Kabbalist called Yehoshua Ben-Shoshan. Gradually an underground movement was formed, whose chief object was to blow up the Dome of the Rock. This would certainly halt the peace process and would also shock Jews worldwide into an appreciation of their religious responsibilities. This spiritual revolution, they believed, would compel God to send the Messiah and the final Redemption. Livni, who was an explosives expert, calculated that they would need twenty-eight precision bombs to demolish the Dome of the Rock without damaging its surroundings. They amassed huge quantities of explosives from a military camp in the Golan Heights. But when the moment of decision arrived in 1982, the group could not find a rabbi to bless their enterprise, and since only Etzion and Ben-Shoshan were willing to go ahead without rabbinical sanction, the plan was shelved.

A religious spirit had emerged in Israel which fostered not compassion but murderous hatred. In 1980, Etzion’s group was responsible for the plot to mutilate five Arab mayors on the West Bank in order to avenge the murder of six yeshiva students in Hebron. The plot was not entirely successful, since only two of the mayors were horribly crippled. The most complete incarnation of this new Judaism of hatred was Rabbi Meir Kahane. He had begun his career in New York, where he had formed the Jewish Defense League to avenge attacks made on Jews by black youths. When he arrived in Israel, Kahane had organized street demonstrations in Jerusalem in protest against the activities of Christian missionaries: his activities, he believed, were sanctioned by certain rabbinical pronouncements about the presence of goyim in the Holy Land. Finally, in 1975, Kahane had moved to Kiryat Arba and changed the name of his organization to Kach (“Thus!”—i.e., by force). His main objective now was to drive Arabs from the State of Israel. In 1980 he was briefly imprisoned for plotting to destroy the Dome of the Rock with a long-range missile.

The people who joined these far-right groups were not primitive or uneducated. Yoel Lerner, who was sent to prison in 1982 for planting a bomb in the Aqsā Mosque, was a graduate of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and a professor of linguistics. After his release, Lerner began to campaign to restore the Sanhedrin to the Temple Mount. All these activities had a dangerously cumulative effect. More people were getting involved in nefarious activities, some of them holding official positions. At the end of March 1983, Rabbi Israel “Ariel” was arrested with thirty-eight yeshiva students on their way to the Ḥaram. Their intention was to reach the remains of the First Temple, under the Herodian platform, by means of an underground tunnel, to celebrate Passover there, and—perhaps—to establish a subterranean settlement. Their object was to force the Muslims to allow Jews to build a synagogue on the Ḥaram. Rabbi Meir Yehuda Getz, who was in charge of the Western Wall, also conducted secret investigations in the Ḥaram vaults and campaigned for a synagogue on the platform. Until 1984, when the Etzion plot to blow up the Dome of the Rock came to light, the idea of a Third Temple had been taboo. Like the Name of God, it was dangerous to speak of it or to give voice to plans for its rebuilding. But now that taboo was being eroded and people were becoming familiar with the idea as a plausible project. In 1984, “Ariel” founded the periodical Tzfia (“Looking Ahead”) to discuss the Third Temple publicly. In 1986 he opened the Museum of the Temple in the Old City, where visitors are shown the vessels, musical instruments, and priestly vestments that have already been made. Many come away with the impression that the Jews are waiting in the wings. As soon as the Muslim shrines on the Ḥaram have been destroyed, by fair means or foul, they are ready to step onto Mount Zion and inaugurate a full-blown ceremonial liturgy. The implications are frightening. American strategists calculated that, in terms of the Cold War, when Russia supported the Arabs and America backed the Israelis, had Etzion’s plot to blow up the Dome of the Rock succeeded, it could have sparked World War Three.

On 9 December 1987, exactly seventy years after Allenby’s conquest of Jerusalem, the popular Palestinian uprising known as the intifā˙dah broke out in Gaza. A few days later the hard-liner general Ariel Sharon moved into his new apartment in the Muslim Quarter of the Old City—a symbolic gesture that expressed the determination of the Israeli right-wing to remain in Arab Jerusalem. But by mid-January the intifā˙dah had also erupted in East Jerusalem: Israeli troops used tear gas on the Ḥaram to disperse demonstrators. Although the intifā˙dah was less intense in Jerusalem than in the rest of the Occupied Territories, there were disturbances and strikes in the city. The Israelis had to accept the fact that twenty years after the annexation of Jerusalem, the Palestinian inhabitants of al-Quds were in total accord with the rebels in the Territories. One practical consequence of the intifā˙dah was that Jerusalem became two cities once again. This time there was no barbed wire, no mined No Man’s Land between East and West Jerusalem. But Arab Jerusalem became a place that Israelis no longer felt able to enter with impunity. When they crossed the invisible partition line, there was now a possibility that they or their cars would be stoned by Palestinian youths and an incident ensue. East Jerusalem had become enemy territory.

The intifā˙dah also achieved striking results internationally. All around the world, the general public became aware of the aggressive nature of the Israeli occupation of Jerusalem and the territories in a new way when they saw armed Israeli soldiers chasing and gunning down stone-throwing children or breaking the bones of their hands. The uprising had been master-minded by the younger generation of Palestinians, who had grown up under the Israeli occupation and had no faith in the PLO’s policies, which had so signally failed to achieve results. The intifā˙dah also impressed the Arab world. On 31 July 1988, King Hussein made a dramatic declaration in which he relinquished Jordan’s claim to the West Bank and East Jerusalem—territory that he now acknowledged to belong to the Palestinian nation. This created a power vacuum which the PLO took advantage of. The leadership of the intifā˙dah urged the PLO to renounce its old unrealistic policies: whether the Palestinians liked it or not, Israel and the United States held the chief cards in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. The PLO must abandon its rejectionist stance and accept UN Resolution 242, recognize the existence of the State of Israel, and renounce terrorism. On 15 November 1988, the PLO took this path and recognized Israel’s right to exist and to security. It also issued the Palestinian Declaration of Independence. There would be a Palestinian state in the West Bank, beside the State of Israel, and the capital of the State of Palestine would be Jerusalem [al-Quds al-Sharif ].

The intifā˙dah also strengthened the hand of the Israeli peace movement. It demonstrated the Palestinians’ absolute insistence on achieving national independence and self-determination too eloquently for an increasing number of Israelis to deny. More significantly, perhaps, it also influenced the thinking of some of the more intransigent. Yitzhak Rabin, the minister of defense, had always taken a tough line on the Palestinian question, but the intifā˙dah finally convinced him that Israel could not continue to hold the Occupied Territories without losing its humanity. The might of the Israeli army could not be used indefinitely to batter into submission the mothers and children who took part in the intifā˙dah. When he became prime minister in 1992, Rabin was prepared to enter into peace negotiations with the PLO. The following year, Israel and the PLO signed the Oslo Agreement, turning over the Gaza Strip and parts of the West Bank (most immediately, the area around Jericho) to a Palestinian administration. Arafat and Rabin shook hands on the lawn of the White House in Washington, D.C.

The Oslo Agreement inspired much opposition. On both sides, people felt that their leaders had made too many concessions. The discussion of the future of Jerusalem was to be postponed until May 1996–a tacit acknowledgment that this would be the most difficult hurdle of all. Just how difficult was shown in the 1993 Jerusalem municipal elections, when Mayor Teddy Kollek was defeated by the conservative Likud candidate Ehud Olmert. Despite his role in the destruction of the Maghribi Quarter and the Arab municipality in 1967, Kollek was regarded as a liberal. He devoted a good deal of time to the Arabs of Jerusalem and sometimes even took their part. He insisted that everything must be done to preserve the Arab way of life in Jerusalem. Nonetheless Kollek was still firmly committed to the “reunification” of the city. All over the world, he fired audiences with his vision of a united city, haunted by the fear of “partition” and barbed-wire boundaries.

Yet the unity of Kollek’s Jerusalem had not meant equality. A recent survey shows that of the 64,880 housing units built in Jerusalem since 1967, only 8,800 were for the Palestinians. Of the city’s nine hundred sanitation workers, only fourteen were assigned to East Jerusalem. No new roads were built to link up the older Arab districts.29 Clearly, even an Israeli “liberal” was discriminating in his benevolence. Moreover, the legal planning procedures adopted by the Israeli government have prevented the Palestinians from using 86 percent of the land in East Jerusalem. A study recently commissioned by the municipality shows that, as a result, 21,000 Palestinian families are currently homeless or inadequately housed. Because of the lack of land legally zoned for housing, it is almost impossible for Palestinians to obtain building permits in East Jerusalem. A home built by a family without permission is subject to demolition. Figures obtained in 1994 indicated that since mid-1987, 222 Palestinian homes had been demolished in East Jerusalem, yet the annual report of the municipality showed that a further 31,413 new housing units for Jewish residents were planned to the north, south, and east of Jerusalem.30 Palestinians have been progressively excluded from al-Quds. Unlike Teddy Kollek, the new mayor, Ehud Olmert, has felt no need to make liberal noises. “I will expand Jerusalem to the east, not to the west,” he has declared. “I can make things happen on the ground to ensure the city will remain united under Israeli control for eternity.”31 It is an attitude that does not bode well for peace.

Olmert has no need to woo Israeli liberals. He came to power by making an alliance with the ultra-Orthodox Jews of Jerusalem, who have grown rapidly in number in recent years. No longer confined to the ghetto of Mea Shearim, they have taken over most of the northern districts of the city. In 1994, 52 percent of the Jewish children under ten in Jerusalem belonged to ultra-Orthodox families. They have no interest in seeking peace with the Arabs. Their concern is to make Jerusalem a more observant city and to keep the secular Jews in line. They want fewer nonkosher restaurants, fewer theaters and places of entertainment open on the Sabbath. Olmert’s supporters do not believe in any sharing of sovereignty with the Palestinians. For the ultra-Orthodox, as for the far-right groups, sharing means partition, and a divided Jerusalem is a dead Jerusalem.

Repeatedly, Israeli governments have insisted that Jerusalem is the eternal and indivisible capital of the Jewish state, and that there can be no question of sharing its sovereignty. The government continues its efforts to disabuse Palestinians of the idea that their capital will be al-Quds. Yet the mood is changing. Since the intifā˙dah, Jerusalem has in effect become a divided city: there are now few places where Arabs and Jews are likely to meet on a normal basis. The main commercial district in West Jerusalem is almost entirely Jewish, the Old City almost entirely Arab. The only point of contact is the belligerently planted ring of Israeli settlements in East Jerusalem. Increasingly, Israelis are coming to accept this as a fact of life. What is the point, some ask, of “controlling” an area that you cannot enter without an armed escort? An opinion poll conducted in May 1995 for the Israel-Palestine Centre for Research and Information revealed that a surprising 28 percent of Israeli Jewish adults were prepared to envisage some form of divided sovereignty in the Holy City, provided that Israel retains control over the Jewish districts.

On 13 May 1995, Feisal Husseini, the PLO representative in Jerusalem, made a speech during a demonstration protesting against the confiscation of Arab land. Standing beneath the walls of the Old City in what had once been No Man’s Land, Husseini said: “I dream of the day when a Palestinian will say ‘Our Jerusalem’ and will mean Palestinians and Israelis, and an Israeli will say ‘Our Jerusalem’ and will mean Israelis and Palestinians.”32 In response, seven hundred prominent Israelis, including writers, critics, artists, and former Knesset members, signed this joint statement:

Jerusalem is ours, Israelis and Palestinians—Muslims, Christians, and Jews.

Our Jerusalem is a mosaic of all the cultures, all the religions, and all the periods that enriched the city, from the earliest antiquity to this very day—Canaanites and Jebusites and Israelites, Jews and Hellenes, Romans and Byzantines, Christians and Muslims, Arabs and Mamelukes, Ottomans and Britons, Palestinians and Israelis. They and all the others who made their contribution to the city have a place in the spiritual and physical landscape of Jerusalem.

Our Jerusalem must be united, open to all and belonging to all its inhabitants, without borders and barbed wire in its midst.

Our Jerusalem must be the capital of the two states that will live side by side in this country—West Jerusalem the capital of the State of Israel and East Jerusalem the capital of the State of Palestine.

Our Jerusalem must be the Capital of Peace.33

If Zion is indeed to be a city of peace instead of a city of war and hatred, some form of condominium must be achieved. A number of solutions have been proposed. Should Jerusalem be an internationally ruled corpus separatum? Should there be Israeli sovereignty with special privileges for the Palestinian authority, a joint Israel-Palestine administration of an undivided city, two separate municipalities, or one, with two distinct governing bodies? Discussion rages fiercely. But unless the underlying principles are clear, all these solutions remain Utopian.

What can the history of Jerusalem teach us about the way forward? In the autumn of 1995, the Israelis opened a year-long festival to celebrate the three-thousandth anniversary of the conquest of the city by King David. The Palestinians objected, seeing the celebrations as propaganda for a wholly Jewish Jerusalem. Yet the story of David’s conquest is, perhaps, more expressive of their cause than the more conservative Israelis imagine. We have seen that all monotheistic conquerors have had to face the fact that Jerusalem was a holy city to other people before them. Since all three faiths insist on the absolute and sacred rights of the individual, the way that the victors treat their predecessors in the Holy City must test the sincerity of their ideals. In these terms King David, as far as we can ascertain from our admittedly imperfect records, stands up fairly well. He did not attempt to eject the Jebusite incumbents from Jerusalem; the Jebusite administration remained in place, and there was no expropriation of sacred sites. Under David, Jerusalem remained a largely Jebusite city. The State of Israel has not measured up to his example. In 1948, thirty thousand Palestinians lost their homes in West Jerusalem, and since the 1967 conquest there has been continual expropriation of Arab land and, increasingly, insulting and dangerous attacks on the Ḥaram al-Sharif. The Israelis have not been the worst conquerors of Jerusalem: they have not slaughtered their predecessors, as the Crusaders did, nor have they permanently excluded them, as the Byzantines banned the Jews from the city. On the other hand, they have not reached the same high standards as Caliph  Umar. As we reflect on the current unhappy situation, it becomes a sad irony that on two occasions in the past, it was an Islamic conquest of Jerusalem that made it possible for Jews to return to their holy city.

Umar. As we reflect on the current unhappy situation, it becomes a sad irony that on two occasions in the past, it was an Islamic conquest of Jerusalem that made it possible for Jews to return to their holy city.  Umar and Saladin both invited Jews to settle in Jerusalem when they replaced Christian rulers there.

Umar and Saladin both invited Jews to settle in Jerusalem when they replaced Christian rulers there.

The 1967 conquest was indeed a mythical occurrence, its symbolism overpowering. Jews had at last truly returned to Zion. Yet from the first, Zion was never merely a physical entity. It was also an ideal. From the Jebusite period, Zion was revered as a city of peace, an earthly paradise of harmony and integration. The Israelite psalmists and prophets also developed this vision. Yet Zionist Jerusalem today falls sadly short of the ideal. Ever since the Crusades, which permanently damaged relations between the three religions of Abraham, Jerusalem has been a nervous, defensive city. It has also, increasingly, been a contentious place. Not only have Jews, Christians, and Muslims fought and competed with one another there, but violent sectarian strife has divided the three main communities internally into bitterly warring factions. Nearly every development in nineteenth-century Jerusalem was either inspired by or led to increased communal rivalry. Today, the Christian sects still snarl at one another over the tomb of Christ, and not long after the emotional conquest of the city during the Six-Day War, religious and secular Israelis were at daggers drawn at the Western Wall. This is not Zion, the haven of rest established by King David.

Constantly Israel insists on the paramount importance of national security. Where the Palestinians want liberation, Israeli Jews want secure borders. Given the atrocities that have scarred Jewish history, this is hardly surprising. Security was one of the first things that people demanded of a city. One of the most important duties of a king in the ancient world was to build powerful fortifications to give people the safety for which they yearned. From its very earliest days, Zion was meant to be such a walled enclave of peace, though from the days of Abdi-Hepa it was also threatened by enemies within and without. Today Jerusalem is once again a beleaguered fortress city, its borders to the east marked by the huge new settlements which crouch around the city like the old Crusader fortifications. But walls are no good if there is deadly trouble within. Pessimistic observers believe that if some equitable solution is not found, Jerusalem is likely to become as violent and dangerous a place for all its inhabitants as Hebron.

Central to the sanctity of Zion from the earliest period was the ideal of social justice. This was one of the chief ways in which an ancient ruler believed that he was imposing the divine order on his city and enabling it to enjoy the peace and security of the gods. The ideal of social justice was crucial to the cult of Baal in Jebusite Jerusalem. The psalmists and prophets insisted that Zion must be a refuge for the poor: the prophets in particular were adamant that devotion to sacred space was pointless if Israelites neglected to care for the vulnerable people in their society. Embedded in the heart of P’s Holiness Code was concern and love for the “stranger” whom Israelites must welcome into their midst. Social justice is also at the core of the Qur ānic message, and in Ayyūbid and Mamluk times, practical compassion was an essential concomitant of the Islamization of Jerusalem. It was also at the root of the socialist Zionism of the veteran pioneers. But sadly the Palestinians have not been made welcome in Zion today, not even under Mayor Teddy Kollek. Israelis often reply that the Palestinians of Jerusalem are treated far better than they would be in an Arab state. This may well be true, but the Palestinians are not comparing themselves with other Arabs but with their Jewish fellow citizens. To insist that a city is “holy” without implementing the justice that is an inalienable part of Jerusalem’s sanctity is to embark upon a dangerous course.

ānic message, and in Ayyūbid and Mamluk times, practical compassion was an essential concomitant of the Islamization of Jerusalem. It was also at the root of the socialist Zionism of the veteran pioneers. But sadly the Palestinians have not been made welcome in Zion today, not even under Mayor Teddy Kollek. Israelis often reply that the Palestinians of Jerusalem are treated far better than they would be in an Arab state. This may well be true, but the Palestinians are not comparing themselves with other Arabs but with their Jewish fellow citizens. To insist that a city is “holy” without implementing the justice that is an inalienable part of Jerusalem’s sanctity is to embark upon a dangerous course.

We can see, perhaps, how dangerous if we look back on some previous regimes that have stressed the importance of possessing the city but have neglected the duty of compassion. There was little charity in Hasmonean Jerusalem: after a committed struggle to preserve the integrity of Jewish Jerusalem, the Hasmoneans became masters of a kingdom that differed little from the cruel Hellenistic despotisms they had been fighting. Their behavior was such that they alienated the Pharisees, who constantly stressed the primacy of charity and loving-kindness. Eventually the Pharisees on several different occasions asked the Romans to depose Jewish monarchs: foreign rule would be preferable to the regime of these bad Jews.

Christian Jerusalem offers a particularly striking instance of the dangers of leaving compassion and absolute respect for the rights of others out of the picture. The New Testament is clear that without charity, faith is worth nothing. Yet this ideal was never integrated with the Christian cult of Jerusalem, perhaps because devotion to the city came quite late and almost took Christians by surprise. Byzantine Jerusalem was capable of giving Christians a powerful experience of the divine, but it was a most uncharitable city. Not only were Christians at one another’s throats but they saw the dismantling and exclusion of paganism and Judaism as essential to the holiness and integrity of their New Jerusalem. Christians gloated over the fate of the Jews; some of the most ascetic monks who had settled in the Judaean desert precisely to be close to the Holy City were murderously anti-Semitic. Eventually the intolerant policies of the Christian emperors so alienated Jews and “heretics” that they became perilously disaffected. Jews greeted the Persian and Muslim invaders of Palestine with enthusiasm and gave them practical help.

Crusader Jerusalem was, of course, an even more cruel city. It was established on slaughter and dispossession. Like the Israelis today, the Crusaders had founded a kingdom that was a foreign enclave in the Near East, dependent upon overseas help and surrounded by hostile states. The entire history of the Crusader kingdom was a struggle for survival. We have seen that the Crusaders shared Israel’s passion for security—with good reason. As a result, there could be little true creativity in Crusader Jerusalem, since art and literature cannot really thrive in such an embattled atmosphere. There were Franks in Jerusalem who realized, like many Israelis today, that their kingdom could not survive as a Western ghetto in the Near East. They must establish normal relations with the surrounding Muslim world. But the Crusaders’ religion of hatred was ingrained: on one occasion they attacked their sole ally in the Islamic world and also turned venomously on one another. The religion of hatred does not work; it so easily becomes self-destructive. The Crusaders lost their state. The barrenness of a piety that sees the possession of a holy place as an end in itself, neglecting the more important duty of charity, is most graphically shown today in the interminable squabble of the Christian sects in the Holy Sepulcher.

In monotheistic terms, it is idolatry to see a shrine or a city as the ultimate goal of religion. Throughout, we have seen that they are symbols that point beyond themselves to a greater Reality. Jerusalem and its sacred sites have been experienced as numinous. They have introduced millions of Jews, Christians, and Muslims to the divine. Consequently they have for many monotheists been viewed as inseparable from the notion of God itself, as we have seen. And, because the divine is not simply a transcendent reality “out there” but something also sensed in the depths of the self, we have also seen that holy places have been regarded as part of a people’s inner world. Sometimes when confronting a shrine, Jews, Christians, and Muslims have felt that they have had a startling and moving encounter with themselves. This can make it very difficult for them to see Jerusalem and its problems objectively. Many of the difficulties arise when religion is seen primarily as a quest for identity. One of the functions of faith is to help us build up a sense of self: to explain where we have come from and why our traditions are distinctive and special. But that is not the sole purpose of religion. All the major world faiths have insisted on the importance of transcending the fragile and voracious ego, which so often denigrates others in its yearning for security. Leaving the self behind is not only a mystical objective; it is required also by the disciplines of compassion, which demand that we put the rights of others before our own selfish desires.

One of the inescapable messages of the history of Jerusalem is that, despite romantic myths to the contrary, suffering does not necessarily make us better, nobler people. All too often, quite the reverse. Jerusalem first became an exclusive city after the Babylonian exile, when the new Judaism was helping Jews to establish a distinct identity in a predominantly pagan world. Second Isaiah had proclaimed that the return to Zion would usher in a new era of peace, but the Golah simply made Jerusalem a bone of contention in Palestine when they excluded the Am ha-Aretz. The experience of persecution at the hands of Rome did not make the Christians more sympathetic to the suffering of others, and al-Quds became a much more aggressively Islamic city after the Muslims suffered at the hands of the Crusaders. It is not surprising, therefore, that the State of Israel, founded shortly after the catastrophe of the Holocaust, has not always implemented policies of sweetness and light. We have seen that the fear of destruction and extinction was one of the main motives that impelled the people of antiquity to build holy cities and temples. In their mythology the ancient Israelites told the story of their journey through the demonic realm of the wilderness—a non-place, where there was no-one and no-thing—to reach the haven of the Promised Land. The Jewish people had endured annihilation on an unprecedented scale in the death camps. It is not surprising that their return to Zion during the Six-Day War shook them to the core and led some of them to believe that there had been a new creation, a new beginning.

But today, increasingly, Israelis are beginning to contemplate the possibility of sharing the Holy City. Sadly, however, most of the committed people who are working for peace are seculars. On both sides of the conflict, religion is becoming increasingly belligerent. The apocalyptic spirituality of extremists who advocate suicide bombing, blowing up other people’s shrines, or driving them from their homes is pursued by only a small minority, but it engenders hatred on a wider scale. On both sides, attitudes harden after an atrocity, and peace becomes a more distant prospect. It was the Zealots who opposed the Peace Party in 66 CE who were chiefly responsible for the destruction of Jerusalem and its Temple, and it was Reynauld of Chatillon, convinced that any truce with the infidel was a sin, who brought down the Crusader kingdom. The religion of hatred can have an effect that is quite disproportionate to the numbers of people involved. Today religious extremists on both sides of the conflict have been responsible for atrocities committed in the name of “God.” On 25 February 1994, Baruch Goldstein gunned down at least forty-eight Palestinian worshippers in the Cave of the Patriarchs in Hebron: today he is revered as a martyr of Israel by the far right. Another martyr is the young woman member of the Islamic group Hamas, who died in a suicide bombing of a Jerusalem bus on 25 August 1995, killing five people and injuring 107. Such actions are a travesty of religion, but they have been frequent in the history of Jerusalem. Once the possession of a land or a city becomes an end in itself, there is no reason to refrain from murder. As soon as the prime duty to respect the divinity enshrined in other human beings is forgotten, “God” can be made to give a divine seal of absolute approval to our own prejudices and desires. Religion then becomes a breeding ground for violence and cruelty.

On 4 November 1995, Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin was murdered after speaking at a peace rally in Tel Aviv. To their horror, Israelis learned that the assassin was another Jew. Yigal Amir, the young student who fired the fatal shots, declared that he had acted under God’s direction and that it was permissible to kill anybody who was prepared to give the sacred land of Israel to the enemy. The religion of hatred seems to have a dynamic of its own. Murderous intransigence can become such a habit that it is directed not only against the enemy but also against co-religionists. Crusader Jerusalem, for example, was bitterly divided against itself, and the Franks were poised on the brink of a suicidal civil war at a time when Saladin was preparing to invade their territory. Their hatred of one another and their chronic feuding was a factor in their defeat at Saladin’s hands at the battle of Hattin.

The tragic murder of Rabin was a shocking revelation to many Israelis of the deep fissures in their own society—divisions which till then they had tried to ignore. The Zionists had come to Palestine to establish a homeland where Jews would be safe from the murderous goyim. Now Jews had begun to kill one another for the sake of that land. All over the world, Jews struggled with the painful realization that they were not merely victims but could also do harm and perpetrate atrocity. Rabin’s death was also a glaring demonstration of the abuse of religion. Since the time of Abraham, the most humane traditions of the religion of Israel had suggested that compassion to other human beings could lead to a divine encounter. So sacred was humanity that it was never right to sacrifice another human life. Yigal Amir, however, subscribed to the more violent ethic of the Book of Joshua. He could see the divine only in the Holy Land. His crime was a frightening demonstration of the dangers of such idolatry.

Kabbalistic myth taught that when the Jews returned to Zion, everything in the world would fall back into its proper place. The assassination of Rabin showed that the return of the Jews to Israel did not mean that everything was right with the world. But this mythology had never been meant to be interpreted literally. Since 1948 the gradual return of the Jewish people to Zion had resulted in the displacement of thousands of Palestinians from their homeland as well as from Jerusalem. We know from the history of Jerusalem that exile is experienced as the end of the world, as a mutilation and a spiritual dislocation. Everything becomes meaningless without a fixed point and the orientation of home. When cut off from the past, the present becomes a desert and the future unimaginable. Certainly the Jews experienced exile as demonic and destructive. Tragically, this burden of suffering has now been passed by the State of Israel to the Palestinians, whatever its original intentions. It is not surprising that Palestinians have not always behaved in an exemplary manner in the course of their own struggle for survival. But, again, there are Palestinians who recognize that compromise may be necessary if they are to regain at least part of their homeland. They have made their own hard journey to the Oslo Accords: that Palestinians should give official recognition to the State of Israel would once have seemed an impossible dream. In exile, Zion became an image of salvation and reconciliation to the Jews. Not surprisingly, al-Quds has become even more precious to the Palestinians in their exile. Two peoples, who have both endured an annihilation of sorts, now seek healing in the same Holy City.

Salvation—secular or religious—must mean more than the mere possession of a city. There must also be a measure of interior growth and liberation. One thing that the history of Jerusalem teaches is that nothing is irreversible. Not only have its inhabitants watched their city destroyed time and again, they have also seen it built up in ways that seemed abhorrent. When the Jews heard of the obliteration of their Holy City, first by Hadrian’s contractors and then by Constantine’s, they must have felt that they would never win their city back. Muslims had to see the desecration of their beloved Ḥaram by the Crusaders, who seemed invincible at the time. All these building projects had been intent on creating facts, but ultimately bricks and mortar were not enough. The Muslims got their city back because the Crusaders became trapped in a dream of hatred and intolerance. In our own day, against all odds, the Jews have returned to Zion and have created their own facts in the settlements around Jerusalem. But, as the long, tragic history of Jerusalem shows, nothing is permanent or guaranteed.

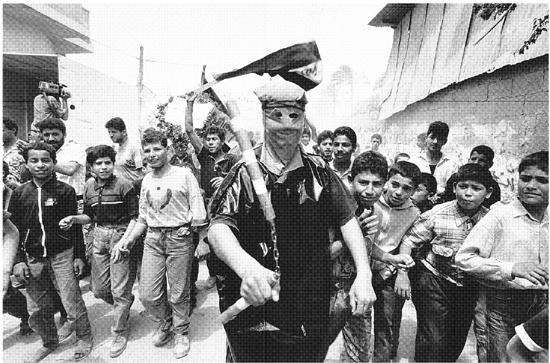

One example of belligerent religion today: members of Hamas, the militant Islamic group which is bitterly opposed to the Oslo Accords, march through Gaza, twirling clubs and chains.

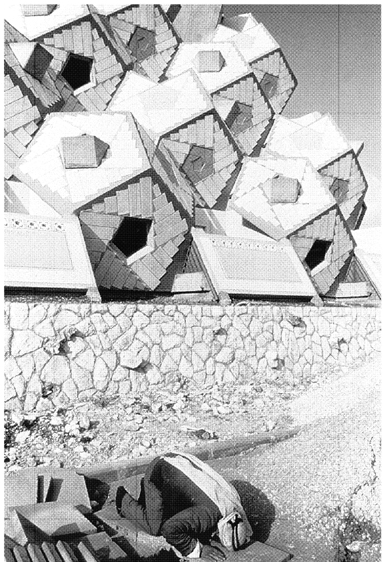

A Palestinian prays beneath a futuristic apartment block, inhabited by ultra-Orthodox Jews, in north Jerusalem. Will construction continue to be used as a weapon of exclusion, or can Jerusalem really become Zion, a city of peace, where Jews and Arabs can encounter the sacred together?

The impermanence and volatility of the affairs of Jerusalem have been dramatically shown in the year that has elapsed since the first edition of this book went to press in January 1996. At that time, hopes for peace were still high. But these hopes were shattered on 25 February 1996, the second anniversary of the Hebron massacre, when a wave of suicide bombings in Jerusalem, Ashkelon, and Tel Aviv killed fifty-seven Israelis. On 11 April, following the killing of six Israeli soldiers by the Islamic group Hizbollah in the Israeli security zone in Lebanon, Israel launched a massive counter-offensive: “Operation Grapes of Wrath,” which consisted of heavy bombardment and over fifteen hundred air-raids, resulting in the deaths of one hundred and sixty Lebanese civilians.

This new round of hostilities showed yet again the fragility of peace in this troubled region, where violence so often breeds more violence. Yet again, as so often in the past, religious extremists seemed to have destroyed all hope of peace. Many Israelis, feeling beset by Islamic militancy, lost confidence in the peace process. When they went to the polls for their general election on 29 May 1996, Binyamin Netanyahu, the hawkish leader of Likud, was elected prime minister of Israel by a narrow majority. Although he pledged to honor the Oslo Accords within reason, Netanyahu had long been critical of Labor’s willingness to cede territory to the Arabs in exchange for peace. Under the new regime, the Israeli withdrawal from the West Bank came to a halt, and eight new settlements were planned in Gaza and the West Bank to increase the settler population in these territories from 130,000 to about 500,000 by the year 2000. Netanyahu also made it clear that there would be no compromise about Jerusalem. The holy city would forever remain Israel’s capital, there would be no sharing of sovereignty, and Israel would not give up a single neighborhood or street in any sector of Jerusalem.

On 23 September, the sacred space of Jerusalem inspired a new wave of tragic violence, when Netanyahu announced his decision to open a tunnel, dating from the second century BCE, which ran alongside the Western Wall and the Ḥaram al-Sharif to exit onto the Via Dolorosa in the very heart of the Muslim Quarter of the Old City. For the Palestinians, already frustrated by the stalling of the peace process and the hardships resulting from the harsh closures imposed upon them in the Occupied Territories after the suicide bombings, this was a violation too far. Immediately there erupted some of the worst violence that Gaza and the West Bank had seen since Israel’s conquest of these territories in 1967. During the Friday prayers at the Aqsā Mosque on 27 September, three Palestinians died and one hundred twenty were injured during clashes with the Israeli police on the Ḥaram; Jewish worshippers were stoned by Palestinians at the Western Wall. When the violence eventually subsided, seventy-five people had been killed and fifteen hundred wounded.

That all this bloodshed should result from the opening of an archaeological site seemed bizarre to many bewildered observers. But to those acquainted with Jerusalem’s tragic history it was a sadly familiar scenario. Archaeology has never been experienced as an entirely neutral activity in Jerusalem. Ever since Constantine had given Bishop Makarios permission to dig up the Tomb of Christ in 325 CE (thereby destroying the pagan Temple of Aphrodite), archaeology has often been used to stake a claim to the sacred territory of the city. It was a discipline associated with acquisition and dispossession. The tunnel in question had been first excavated by the Israeli Ministry for Religious Affairs in 1968 as part of their archaeological explorations of the newly conquered city. Previous discussions about opening the tunnel’s new door into the Via Dolorosa had concluded that the project was too sensitive and potentially disruptive to be executed. Netanyahu, however, chose to reject the warnings of his security advisers in order to demonstrate his government’s determination to tighten its grasp on Jerusalem.

It is true that the offending tunnel did not in fact penetrate the Ḥaram itself. But at times of political tension, people in Jerusalem have not always been able to respond rationally when they have perceived a threat to their holy places. This had certainly been the experience of the Jewish people, ever since Antiochus Epiphanes had desecrated their Temple in 170 BCE. Later most Jews had been able to accept the rule of Rome, but not if there was any threat to the Temple’s sanctity. Pontius Pilate had discovered this when he had provocatively installed the standards bearing the bust of the Roman Emperor in the Antonia Fortress, even though these had remained outside the officially sacred area. This hardened Roman governor was, Josephus tells us, dismayed and shocked by the Jews’ apparently suicidal determination to defend the holiness of their Temple.