In Jerusalem, more than in any other place I have visited, history is a dimension of the present. Perhaps this is so in any disputed territory, but it struck me forcibly the first time I went to work in Jerusalem in 1983. First, I was surprised by the strength of my own reaction to the city. It was strange to be walking around a place that had been an imaginative reality in my life ever since I was a small child and had been told tales of King David or Jesus. As a young nun, I was taught to begin my morning meditation by picturing the biblical scene I was about to contemplate, and so conjured up my own image of the Garden of Gethsemane, the Mount of Olives, or the Via Dolorosa. Now that I was going about my daily business among these very sites, I discovered that the real city was a far more tumultuous and confusing place. I had, for example, to take in the fact that Jerusalem was clearly very important to Jews and Muslims too. When I saw caftaned Jews or tough Israeli soldiers kissing the stones of the Western Wall or watched the crowds of Muslim families surging through the streets in their best clothes for Friday prayers at the Ḥaram al-Sharif, I became aware for the first time of the challenge of religious pluralism. People could see the same symbol in entirely different ways. There was no doubting the attachment of any of these people to their holy city, yet they had been quite absent from my Jerusalem. Still, the city remained mine as well: my old images of biblical scenes were a constant counterpoint to my firsthand experience of twentieth-century Jerusalem. Associated with some of the most momentous events of my life, Jerusalem was somehow built into my own identity.

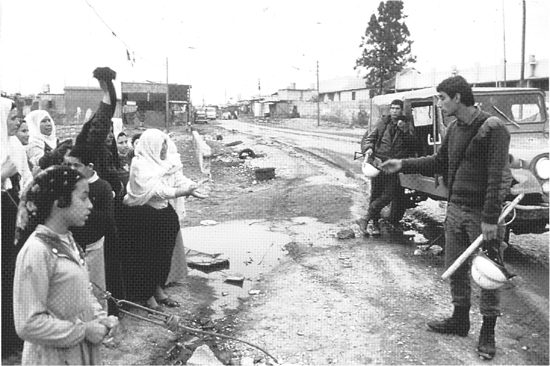

Yet as a British citizen, I had no political claim to the city, unlike my new colleagues and friends in Jerusalem. Here again, as Israelis and Palestinians presented their arguments to me, I was struck by the vivid immediacy of past events. All could cite, in sometimes minute detail, the events leading up to the creation of the State of Israel in 1948 or the Six-Day War in 1967. Frequently I noted how these depictions of the past centered on the question of who had done what first. Who had been the first to resort to violence, the Zionists or the Arabs? Who had first noticed the potential of Palestine and developed the country? Who had lived in Jerusalem first, the Jews or the Palestinians? When they discussed the troubled present, both Israelis and Palestinians turned instinctively to the past, their polemic coursing easily from the Bronze Age through the Middle Ages to the twentieth century. Again, when Israelis and Palestinians proudly showed me around their city, the very monuments were drawn into the conflict.

On my first morning in Jerusalem, I was instructed by my Israeli colleagues how to spot the stones used by King Herod, with their distinctively beveled edges. They seemed ubiquitous and a perpetual reminder of a Jewish commitment to Jerusalem that could be dated back (in this case) to the first century BCE—long before Islam appeared on the scene. Constantly, as we passed construction crews in the Old City, I was told how Jerusalem had been utterly neglected by the Ottomans when they had ruled the city. It had come to life again only in the nineteenth century, thanks, largely, to Jewish investment—look at the windmill built by Sir Moses Montefiore and the hospitals funded by the Rothschild family. It was due to Israel that the city was thriving as never before.

Separated by decades of hostility, Israelis and Palestinians both claim that Jerusalem belongs to them. The question could deepen the rift and make peace and coexistence impossible.

My Palestinian friends showed me a very different Jerusalem. They pointed out the splendors of the Ḥaram al-Sharif and the exquisite madāris, Muslim schools, built around its borders by the Mamluks as evidence of the Muslim commitment to Jerusalem. They took me to the shrine of Nebī Mūsā near Jericho, built to defend Jerusalem against the Christians, and the extraordinary Umayyad palaces nearby. When we drove through Bethlehem once, my Palestinian host stopped the car beside Rachel’s roadside tomb to point out passionately that the Palestinians had cared for this Jewish shrine for centuries—a pious devotion for which they had been ill rewarded.

One word kept recurring throughout. Even the most secular Israelis and Palestinians pointed out that Jerusalem was “holy” to their people. The Palestinians even called the city al-Quds, “the Holy,” though the Israelis scornfully waved this aside, pointing out that Jerusalem had been a holy city for Jews first, and that it had never been as important to the Muslims as Mecca and Medina. But what did the word “holy” mean in this context? How could a mere city, full of fallible human beings and teeming with the most unholy activities, be sacred? Why did those Jews who professed a militant atheism care about the holy city and feel so possessive about the Western Wall? Why should an unbelieving Arab be moved to tears the first time he stood in the Mosque of al-Aqsā? I could see why the city was holy to Christians, since Jerusalem had been the scene of Jesus’s death and resurrection: it had witnessed the birth of the faith. But the formative events of both Judaism and Islam had happened far away from Jerusalem, in the Sinai Peninsula or the Arabian Hijaz. Why, for example, was Mount Zion in Jerusalem a holy place for Jews instead of Mount Sinai, where God had given the Law to Moses and made his covenant with Israel? Clearly, I had been wrong to assume that the holiness of a city depended upon its associations with the events of salvation history, the mythical account of God’s intervention in the affairs of humanity. It was to find out what a holy city was that I decided to write this book.

What I have discovered is that even though the word “holy” is bandied around freely in connection with Jerusalem, as though its meaning were self-evident, it is in fact quite complex. Each one of the three monotheistic religions has developed traditions about the city that are remarkably similar. Furthermore, the devotion to a holy place or a holy city is a near-universal phenomenon. Historians of religion believe that it is one of the earliest manifestations of faith in all cultures. People have developed what has been called a sacred geography that has nothing to do with a scientific map of the world but which charts their interior life. Earthly cities, groves, and mountains have become symbols of this spirituality, which is so omnipresent that it seems to answer a profound human need, whatever our beliefs about “God” or the supernatural. Jerusalem has—for different reasons—become central to the sacred geography of Jews, Christians, and Muslims. This makes it very difficult for them to see the city objectively, because it has become bound up with their conception of themselves and the ultimate reality—sometimes called “God” or the sacred—that gives our mundane life meaning and value.

There are three interconnected concepts that will recur in the following pages. First is the whole notion of God or the sacred. In the Western world, we have tended to view God in a rather anthropomorphic and personalized manner, and as a result, the whole notion of the divine frequently appears incoherent and incredible. Since the word “God” has become discredited to many people because of the naïve and often unacceptable things that have been asserted and done in “his” name, it may be easier to use the term “sacred” instead. When they have contemplated the world, human beings have always experienced a transcendence and mystery at the heart of existence. They have felt that it is deeply connected with themselves and with the natural world, but that it also goes beyond. However we choose to define it—it has been called God, Brahman, or Nirvana—this transcendence has been a fact of human life. We have all experienced something similar, whatever our theological opinions, when we listen to a great piece of music or hear a beautiful poem and feel touched within and lifted, momentarily, beyond ourselves. We tend to seek out this experience, and if we do not find it in one setting—in a church or synagogue, for example—we will look elsewhere. The sacred has been experienced in many ways: it has inspired fear, awe, exuberance, peace, dread, and compelling moral activity. It represents a fuller, enhanced existence that will complete us. It is not merely felt as a force “out there” but can also be sensed in the depths of our own being. But like any aesthetic experience, the sense of the sacred needs to be cultivated. In our modern secular society, this has not always been a priority, and so, like any unused capacity, it has tended to wither away. In more traditional societies, the ability to apprehend the sacred has been regarded as of crucial importance. Indeed, without this sense of the divine, people often felt that life was not worth living.

This is partly because human beings have always experienced the world as such a painful place. We are the victims of natural disasters, of mortality, extinction, and human injustice and cruelty. The religious quest has usually begun with the perception that something has gone wrong, that, as the Buddha put it, “Existence is awry.” Besides the common shocks that flesh is heir to, we all suffer personal distress that makes apparently unimportant setbacks overwhelmingly upsetting. There is a sense of abandonment that makes such experiences as bereavement, divorce, broken friendship, or even losing a beloved object seem, sometimes, part of an underlying and universal ill. Often this interior dis-ease is characterized by a sense of separation. There appears to be something missing from our lives; our existence seems fragmented and incomplete. We have an inchoate feeling that life was not meant to be thus and that we have lost something essential to our well-being—even though we would be hard put to explain this rationally. This sense of loss has surfaced in many ways. It is apparent in the Platonic image of the twin soul from which we have been separated at birth and in the universal myth of the lost paradise. In previous centuries, men and women turned to religion to assuage this pain, finding healing in the experience of the sacred. Today in the West, people sometimes have recourse to psychoanalysis, which has articulated this sense of a primal separation in a more scientific idiom. Thus it is associated with memories of the womb and the traumatic shock of birth. However we choose to see it, this notion of separation and a yearning for some kind of reconciliation lies at the heart of the devotion to a holy place.

The second concept we must discuss is the question of myth. When people have tried to speak about the sacred or about the pain of human existence, they have not been able to express their experience in logical, discursive terms but have had recourse to mythology. Even Freud and Jung, who were the first to chart the so-called scientific quest for the soul, turned to the myths of the classical world or of religion when they tried to describe these interior events, and they made up some new myths of their own. Today the word “myth” has been rather debased in our culture; it is generally used to mean something that is not true. Events are dismissed because they are “only” myths. This is certainly true in the debate about Jerusalem. Palestinians claim that there is absolutely no archaeological evidence for the Jewish kingdom founded by King David and that no trace of Solomon’s Temple has been found. The Kingdom of Israel is not mentioned in any contemporary text but only in the Bible. It is quite likely, therefore, that it is merely a “myth.” Israelis have also discounted the story of the Prophet Muhammad’s ascent to heaven from the Ḥaram al-Sharif in Jerusalem—a myth that lies at the heart of the Muslim devotion to al-Quds—as demonstrably absurd. But this, I have come to believe, is to miss the point. Mythology was never designed to describe historically verifiable events that actually happened. It was an attempt to express their inner significance or to draw attention to realities that were too elusive to be discussed in a logically coherent way. Mythology has been well defined as an ancient form of psychology, because it describes the inner reaches of the self which are so mysterious and yet so fascinating to us. Thus the myths of “sacred geography” express truths about the interior life. They touch on the obscure sources of human pain and desire and can thus unleash very powerful emotions. Stories about Jerusalem should not be dismissed because they are “only” myths: they are important precisely because they are myths.

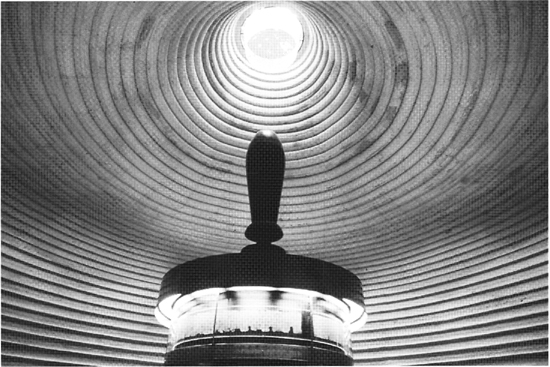

The Jerusalem question is explosive because the city has acquired mythical status. Not surprisingly, people on both sides of the present conflict and in the international community frequently call for a rationalized debate about rights and sovereignty, divorced from all this emotive fiction. It would be nice if this were possible. But it is never safe to say that we have risen above our need for mythology. People have often tried to eradicate myth from religion in the past. Prophets and reformers in ancient Israel, for example, were extremely concerned to separate their faith from the mythology of the indigenous Canaanites. They did not succeed, however. The old stories and legends surfaced again powerfully in the mysticism of Kabbalah, a process that has been described as the triumph of myth over the more rational forms of religion. In the history of Jerusalem we shall see that people turned instinctively toward myth when their lives became particularly troubled and they could find no consolation in a more cerebral ideology. Sometimes outer events seemed so perfectly to express a people’s inner reality that they immediately assumed mythical status and inspired a burst of mythologized enthusiasm. Two such events have been the discovery of the Tomb of Christ in the fourth century and the Israeli conquest of Jerusalem in 1967. In both cases, the people concerned thought they had left this primitive way of thinking far behind, but the course of events proved too strong for them. The catastrophes which have befallen the Jewish and the Palestinian people in our own century have been of such magnitude that it has not been surprising that myth has once again come to the fore. For good or ill, therefore, a consideration of the mythology of Jerusalem is essential, if only to illuminate the desires and behavior of people who are affected by this type of spirituality.

The Shrine of the Book in West Jerusalem houses the Dead Sea Scrolls. The sexual imagery embodied in the shrine shows how deeply the secular State of Israel has assimilated the ancient myths of sacred geography.

The last term that we must consider before embarking on the history of Jerusalem is symbolism. In our scientifically oriented society, we no longer think naturally in terms of images and symbols. We have developed a more logical and discursive mode of thought. Instead of looking at physical phenomena imaginatively, we strip an object of all its emotive associations and concentrate on the thing itself. This has changed the religious experience for many people in the West, a process that, as we shall see, began in the sixteenth century. We tend to say that something is only a symbol, essentially separate from the more mysterious reality that it represents. This was not so in the premodern world, however. A symbol was seen as partaking in the reality to which it pointed; a religious symbol thus had the power of introducing worshippers to the sacred realm. Throughout history, the sacred has never been experienced directly—except, perhaps, by a very few extraordinary human beings. It has always been felt in something other than itself. Thus the divine has been experienced in a human being—male or female—who becomes an avatar or incarnation of the sacred; it has also been found in a holy text, a law code, or a doctrine. One of the earliest and most ubiquitous symbols of the divine has been a place. People have sensed the sacred in mountains, groves, cities, and temples. When they have walked into these places, they have felt that they have entered a different dimension, separate from but compatible with the physical world they normally inhabit. For Jews, Christians, and Muslims, Jerusalem has been such a symbol of the divine.

This is not something that happens automatically Once a place has been experienced as sacred in some way and has proved capable of giving people access to the divine, worshippers have devoted a great deal of creative energy to helping others to cultivate this sense of transcendence. We shall see that the architecture of temples, churches, and mosques has been symbolically important, often mapping out the inner journey that a pilgrim must take to reach God. Liturgy and ritual have also heightened this sense of sacred space. In the Protestant West, people have often inherited a mistrust of religious ceremonial, seeing it as so much mumbo-jumbo. But it is probably more accurate to see liturgy as a form of theater, which can provide a powerful experience of the transcendent even in a wholly secular context. In the West, drama had its origins in religion: in the sacred festivals of ancient Greece and the Easter celebrations in the churches and cathedrals of medieval Europe. Myths have also been devised to express the inner meaning of Jerusalem and its various shrines.

One of these myths is what the late Romanian-American scholar Mircea Eliade has called the myth of eternal return, which he found in almost all cultures. According to this mode of thought, all objects that we encounter here on earth have their counterpart in the divine sphere. One can see this myth as an attempt to express the sense that our life here below is somehow incomplete and separated from a fuller and more satisfactory existence elsewhere. All human activities and skills also have a divine prototype: by copying the actions of the gods, people can share in their divine life. This imitatio dei is still observed today. People continue to rest on the Sabbath or eat bread and drink wine in church—actions which are meaningless in themselves—because they believe that in some sense God once did the same. The rituals at a holy place are another symbolic way of imitating the gods and entering their fuller and more potent mode of existence. The same myth is also crucial to the cult of the holy city, which can be seen as the replica of the home of the gods in heaven; a temple is regarded as the reproduction of a particular deity’s celestial palace. By copying its heavenly archetype as minutely as possible, a temple could also house the god here on earth.

In the cold light of rational modernity, such myths appear ridiculous. But these ideas were not worked out first and then applied to a particular “holy” location. They were an attempt to explain an experience. In religion, experience always comes before the theological explanation. People first felt that they had apprehended the sacred in a grove or on a mountain peak. They were sometimes helped to do so by the aesthetic devices of architecture, music, and liturgy, which lifted them beyond themselves. They then sought to explain this experience in the poetic language of mythology or in the symbols of sacred geography. Jerusalem turned out to be one of those locations that “worked” for Jews, Christians, and Muslims because it did seem to introduce them to the divine.

One further remark is necessary. The practices of religion are closely akin to those of art. Both art and religion try to make some ultimate sense of a flawed and tragic world. But religion is different from art because it must have an ethical dimension. Religion can perhaps be described as a moral aesthetic. It is not enough to experience the divine or the transcendent; the experience must then be incarnated in our behavior towards others. All the great religions insist that the test of true spirituality is practical compassion. The Buddha once said that after experiencing enlightenment, a man must leave the mountaintop and return to the marketplace and there practice compassion for all living beings. This also applies to the spirituality of a holy place. Crucial to the cult of Jerusalem from the very first was the importance of practical charity and social justice. The city cannot be holy unless it is also just and compassionate to the weak and vulnerable. But sadly, this moral imperative has often been overlooked. Some of the worst atrocities have occurred when people have put the purity of Jerusalem and the desire to gain access to its great sanctity before the quest for justice and charity.

All these underlying currents have played their part in Jerusalem’s long and turbulent history. This book will not attempt to lay down the law about the future of Jerusalem. That would be a presumption. It is merely an attempt to find out what Jews, Christians, and Muslims have meant when they have said that the city is “holy” to them and to point out some of the implications of Jerusalem’s sanctity in each tradition. This seems just as important as deciding who was in the city first and who, therefore, should own it, especially since the origins of Jerusalem are shrouded in such obscurity.