GENERATIONS

In the spring of 1984, I went to the northwest of France, to Normandy, to prepare an NBC documentary on the fortieth anniversary of D-Day, the massive and daring Allied invasion of Europe that marked the beginning of the end of Adolf Hitler’s Third Reich. I was well prepared with research on the planning for the invasion—the numbers of men, ships, airplanes, and other weapons involved; the tactical and strategic errors of the Germans; and the names of the Normandy villages that in the midst of battle provided critical support to the invaders. What I was not prepared for was how this experience would affect me emotionally.

The D-Day fortieth-anniversary project awakened my earliest memories. Between the ages of three and five I lived on an Army base in western South Dakota and spent a good deal of my time outdoors in a tiny helmet, shooting stick guns at imaginary German and Japanese soldiers. My father, Red Brokaw, then in his early thirties, was an all-purpose Mr. Fix-It and operator of snow-plows and construction machinery, part of a crew that kept the base functioning. When he was drafted, the base commander called him back, reasoning he was more valuable in the job he had. When Dad returned home, it was the first time I saw my mother cry. These were powerful images for an impressionable youngster.

The war effort was all around us. Ammunition was tested on the South Dakota sagebrush prairie before being shipped out to battlefront positions. I seem to remember that one Fourth of July the base commander staged a particularly large firing exercise as a wartime substitute for fireworks. Neighbors always seemed to be going to or coming home from the war. My grandfather Jim Conley followed the war’s progress in Time magazine and on his maps. There was even a stockade of Italian prisoners of war on the edge of the base. They were often free to wander around the base in their distinctive, baggy POW uniforms, chattering happily in Italian, a curious Mediterranean presence in that barren corner of the Great Plains.

At the same time, my future wife, Meredith Auld, was starting life in Yankton, South Dakota, the Missouri River community that later became the Brokaw family home as well. She saw her father only once during her first five years. He was a front-line doctor with the Army’s 34th Regiment and was in the thick of battle from North Africa all the way through Italy. When he returned home, he established a thriving medical practice and was a fixture at our high school sports games. He never spoke to any of us of the horrors he had seen. When one of his sons wore as a casual jacket one of Doc Auld’s Army coats with the major’s insignia still attached, I remember thinking, “God, Doc Auld was a big deal in the war.”

Yet when I arrived in Normandy, those memories had receded, replaced by days of innocence in the fifties, my life as a journalist covering the political turmoil brought on by Vietnam, the social upheaval of the sixties, and Watergate in the seventies. I was much more concerned about the prospects of the Cold War than the lessons of the war of my early years.

I was simply looking forward to what I thought would be an interesting assignment in a part of France celebrated for its hospitality, its seafood, and its Calvados, the local brandy made from apples.

Instead, I underwent a life-changing experience. As I walked the beaches with the American veterans who had landed there and now returned for this anniversary, men in their sixties and seventies, and listened to their stories in the cafés and inns, I was deeply moved and profoundly grateful for all they had done. I realized that they had been all around me as I was growing up and that I had failed to appreciate what they had been through and what they had accomplished. These men and women came of age in the Great Depression, when economic despair hovered over the land like a plague. They had watched their parents lose their businesses, their farms, their jobs, their hopes. They had learned to accept a future that played out one day at a time. Then, just as there was a glimmer of economic recovery, war exploded across Europe and Asia. When Pearl Harbor made it irrefutably clear that America was not a fortress, this generation was summoned to the parade ground and told to train for war. They left their ranches in Sully County, South Dakota, their jobs on the main street of Americus, Georgia, they gave up their place on the assembly lines in Detroit and in the ranks of Wall Street, they quit school or went from cap and gown directly into uniform.

They answered the call to help save the world from the two most powerful and ruthless military machines ever assembled, instruments of conquest in the hands of fascist maniacs.

They faced great odds and a late start, but they did not protest. At a time in their lives when their days and nights should have been filled with innocent adventure, love, and the lessons of the workaday world, they were fighting, often hand to hand, in the most primitive conditions possible, across the bloodied landscape of France, Belgium, Italy, Austria. They fought their way up a necklace of South Pacific islands few had ever heard of before and made them a fixed part of American history—islands with names like Iwo Jima, Guadalcanal, Okinawa. They were in the air every day, in skies filled with terror, and they went to sea on hostile waters far removed from the shores of their homeland.

New branches of the services were formed to get women into uniform, working at tasks that would free more men for combat. Other women went to work in the laboratories and in the factories, developing new medicines, building ships, planes, and tanks, and raising the families that had been left behind.

America’s preeminent physicists were engaged in a secret race to build a new bomb before Germany figured out how to harness the atom as a weapon. Without their efforts and sacrifices our world would be a far different place today.

When the war was over, the men and women who had been involved, in uniform and in civilian capacities, joined in joyous and short-lived celebrations, then immediately began the task of rebuilding their lives and the world they wanted. They were mature beyond their years, tempered by what they had been through, disciplined by their military training and sacrifices. They married in record numbers and gave birth to another distinctive generation, the Baby Boomers. They stayed true to their values of personal responsibility, duty, honor, and faith.

They became part of the greatest investment in higher education that any society ever made, a generous tribute from a grateful nation. The GI Bill, providing veterans tuition and spending money for education, was a brilliant and enduring commitment to the nation’s future. Campus classrooms and housing were overflowing with young men in their mid-twenties, many of whom had never expected to get a college education. They left those campuses with degrees and a determination to make up for lost time. They were a new kind of army now, moving onto the landscapes of industry, science, art, public policy, all the fields of American life, bringing to them the same passions and discipline that had served them so well during the war.

They helped convert a wartime economy into the most powerful peacetime economy in history. They made breakthroughs in medicine and other sciences. They gave the world new art and literature. They came to understand the need for federal civil rights legislation. They gave America Medicare.

They helped rebuild the economies and political institutions of their former enemies, and they stood fast against the totalitarianism of their former allies, the Russians. They were rocked by the social and political upheaval of the sixties. Many of them hated the long hair, the free love, and, especially, what they saw as the desecration of the flag. But they didn’t give up on the new generation.

They weren’t perfect. They made mistakes. They allowed McCarthyism and racism to go unchallenged for too long. Women of the World War II generation, who had demonstrated so convincingly that they had so much more to offer beyond their traditional work, were the underpinning for the liberation of their gender, even as many of their husbands resisted the idea. When a new war broke out, many of the veterans initially failed to recognize the differences between their war and the one in Vietnam.

There on the beaches of Normandy, I began to reflect on the wonders of these ordinary people whose lives are laced with the markings of greatness. At every stage of their lives they were part of historic challenges and achievements of a magnitude the world had never before witnessed.

Although they were transformed by their experiences and quietly proud of what they had done, their stories did not come easily. They didn’t volunteer them. I had to keep asking questions or learn to stay back a step or two as they walked the beaches themselves, quietly exchanging memories. NBC News had brought to Normandy several of those ordinary Americans, including Gino Merli, of Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, who landed on D-Day and later won the Congressional Medal of Honor for holding off an attacking wave of German soldiers. This quiet man had stayed at his machine gun, blazing away at the Germans, covering the withdrawal of his fellow Americans, until his position was overrun. He faked his own death twice as the Germans swept past, and then he went back to his machine gun to cut them down from behind. His cunning and courage saved his fellow soldiers, and in a night of battle he killed more than fifty attacking Germans.

We also brought Harry Garton of Bucks County, Pennsylvania, who lost both legs to a land mine later in the war. Merli and Garton had both been in the Army’s “Big Red One,” the 1st Division. This trip to Normandy was their first time meeting each other and their first journey back to those beaches since they’d landed under greatly different circumstances forty years earlier. Quite coincidentally, they realized they’d been in the same landing craft, so they had matching memories of the chaos and death all around them. Garton said, “I remember all the bodies and all the screaming.” Were they scared?, I asked them. Both men had the same answer: they felt alternating fear, rage, calm, and, most of all, an overpowering determination to survive.

As they made their way along Omaha Beach in 1984, they stopped and pointed to a low-lying bluff leading to higher ground. Merli said, “Remember that?” They both stared at a steep, sandy slope, an ordinary beach approach to my eye. “Remember what?” I asked. “Oh,” Merli said, “that hillside was loaded with mines, and a unit of sappers had gone first, to find where the mines were. A number of those guys were lying on the hillside, their legs shattered by the explosions. They’d shot themselves up with morphine and they were telling where it was now safe to step. They were about twenty-five yards apart, our guys, calmly telling us how to get up the hill. They were human markers.” Garton said, “When I got to the top of that hill, I thought I’d live at least until the next day.”

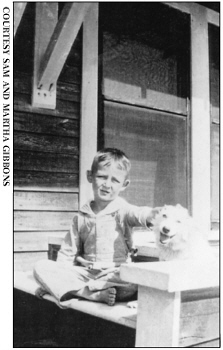

Sam Gibbons and Snow Ball at Grandparents Gibbonses’ house, Haven Beach, Florida, 1926

Sam Gibbons, 1927

They described the scene as calmly as if they were remembering an egg-toss at a Sunday social back home. It was an instructive moment for me, one of many, and so characteristic. The war stories come reluctantly, and they almost never reflect directly on the bravery of the storyteller. Almost always he or she is singling out someone else for praise.

On that trip to Normandy, I ducked into a small café for lunch on a rainy Sunday. A tall, familiar-looking American approached with a big grin and introduced himself: “Tom, Congressman Sam Gibbons of Florida.”

I knew of Gibbons, a veteran Democrat from central Florida, a member of the Ways and Means Committee, but I didn’t know much about him.

“Congressman,” I said, “what are you doing here?” “Oh, I was here forty years ago,” he said with a laugh, “but it was a little different then.” With that he clicked a small brass-and-steel cricket he was holding and laughed again.

I knew of the cricket. The paratroopers of the 101st and 82nd Airborne divisions were given the crickets to click if they were separated from their units. As it turned out, most of them were. When I asked Gibbons what had happened to him that day, he sat down and, staring at a far wall, told a harrowing tale that went on for half an hour. In the café, all of us listening were hypnotized by this gangly, jug-eared man in his sixties and the story he was sharing.

Gibbons, a captain in the 101st, was all alone when he landed in a French farm field in the predawn darkness. Using his cricket, he clicked until he got an answer, and then formed a squad of American paratroopers out of other units. They had no idea where they were, and for a time Gibbons thought the invasion had failed because there was no sign of American troops besides his small patched-up patrol.

Gibbons and the other paratroopers with him moved along the country roads between the hedgerows, getting ambushed and fighting back, moving on again, trying to figure out just where they were. Gibbons even tried to converse with the terrified French villagers, using his high school Spanish. It didn’t help. It was eighteen hours before they hooked up with other units.

His original objective, holding the bridges over the Douve River at a village called St. Côme-du-Mont, turned out to have been a far tougher assignment than the D-Day planners had realized. It took a whole division, fire support from U.S. cruisers offshore, and tanks to take control of the river crossings. By the third day, Gibbons was exhausted, he said, and he was one of only six hundred or so of the two thousand men in his battalion still on his feet. The others were all dead or wounded.

As he sat there on that rainy afternoon, describing these scenes from passing images of his memory, Gibbons’s tough-guy demeanor began to change. He softened and then began to weep. His wife touched his arm and said he didn’t have to go on. But he did, and those of us in his tiny audience were enthralled.

Later, Gibbons told me that he fought his way all across Europe and into Germany without a scratch. His brother, also in the Army, was badly wounded, and when the war was over they both enrolled at the University of Florida law school. They didn’t talk much about the war until one Saturday in the fall term when they decided to try to count up the young Floridians they had known who hadn’t made it back. Gibbons says, “When we got to a hundred we stopped counting and said, ‘To hell with this.’ ”

Gibbons went on to his career in politics, first in the Florida legislature and then seventeen terms in the U.S. House of Representatives, where he became a champion of free trade as a means of keeping international tensions under control, a lesson he learned from the politics of World War II. He was also a solid member of the ruling Democratic majorities. He initially supported the Vietnam War but says now, “The sorriest vote I ever cast was for the Tonkin Gulf resolution,” the congressional mandate engineered by President Johnson so he could step up the American efforts in Vietnam.

Gibbons’s personal war experience rarely came up publicly again, but it did one day in the fall of 1995, after the Republican Revolution of the year before, when a well-organized class of GOP Baby Boomers took control of the House, determined to deconstruct many of the policies put in place by Democrats during their long congressional rule.

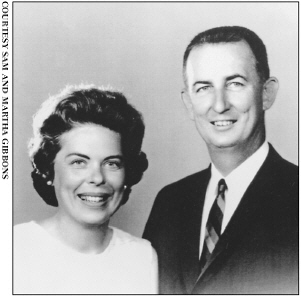

Martha and Sam Gibbons, 1962

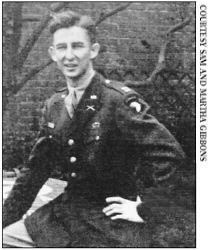

Sam Gibbons, U.S. Army

Gibbons, now in the minority on the Ways and Means Committee, was furious. The new Republican leadership had cut off debate on Medicare reforms without a hearing. Gibbons stormed from the room, shouting, “You’re a bunch of dictators, that’s all you are. . . . I had to fight you guys fifty years ago.” Gibbons then grabbed the tie of the startled Republican chairman, demanding, “Tell them what you did in there, tell them what you did.”

Watching this scene play out on CNN, many of my colleagues were puzzled by the eruption in the normally calm demeanor of Congressman Gibbons. I smiled to myself, thinking of that day in Normandy in 1944 when Gibbons, who was then just twenty-four, learned something about fighting for what you believe in.

When I returned to Normandy for the fiftieth anniversary of D-Day, my wife, Meredith, joined me. By 1994, I felt a kind of missionary zeal for the men and women of World War II, spreading the word of their remarkable lives. I was inspired by them but also by the work of my friend Stephen Ambrose, the plain-talking historian who had written an account of the invasion called D-Day June 6, 1944: The Climactic Battle of World War II.

From him I learned that the men told the stories best themselves. So I told Meredith, “Whenever one of these guys comes over to say hello, just ask, ‘Where were you that day?’ You’ll hear some unbelievable stories.” And so we did, wherever we went. What we did not know at the time was that an old family friend back in our hometown of Yankton, South Dakota, had played a critical role in D-Day planning.

In fact, we were only vaguely aware that Hod Nielsen had anything to do with World War II. To us, he was the keeper of the flame of high school athletics as a sportswriter and radio sports-caster. In his columns and on the air, he chronicled the individual and team achievements of our local high school, writing generously of the smallest victories, celebrating the stars but always finding some admirable trait to highlight in his descriptions of those of us who were known mostly for just showing up.

What I did not know—nor did any of my high school contemporaries—was that Hod Nielsen, who spent so many of the postwar years making sure our little triumphs received notice, had been a daring photo reconnaissance pilot during World War II. He was in the unit that flew lightly armored P-38s over Normandy just before the invasion, photographing the beaches and fields for the military planners. As soon as they returned from that mission, they were hustled back to Washington to report directly to the legendary commander of the Army Air Corps, General Henry “Hap” Arnold. It’s also likely they were spirited out of England quickly to diminish the chances that the identity of their reconnaissance targets would somehow leak.

President Bill Clinton’s presentation to Sam Gibbons,

recalling Gibbons’s participation in D-Day—

White House Family Dining Room, May 14, 1994

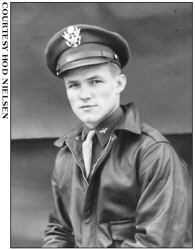

Hod Nielsen, England, 1942

Hod Nielsen, England, 1943, returning from a mission

Hod Nielsen, 1995

Hod was one of many in our midst who kept his war years to himself, preferring to concentrate on the generations that followed. He is so characteristic of that time and place in American life. One of four sons of hardworking Scandinavian immigrants, whom he remembers for their loving and frugal ways, Hod doesn’t recall a missed meal or a complaint about hard times during the height of the Great Depression.

All four boys in his family were in the service. One brother was killed in action when his bomber was shot down over Europe. The war had been a family trial but also an adventure. Hod had a lot of fun as a freewheeling young officer during pilot training. He managed to avoid getting shot down during numerous reconnaissance missions. He saw a lot of the United States and the world, but when the war was over Hod wanted to return to the familiar life he had known in South Dakota. He says now, “I thought then, If this is the fast track, I don’t want any part of it.”

Instead, he returned to a career in broadcasting and sportswriting. He’s been at it for more than half a century, and he can still get excited about the local high school team’s coming football season. He can tell you the whereabouts and the personal and professional fortunes of the athletes long gone from that small city along the Missouri River.

To get a favorable mention in a Hod Nielsen column requires more than a winning touchdown or all-state recognition. He is as likely to write about an athlete’s musical ability or scholastic standing or family. As a result, it’s always been a little special to read your name beneath his byline. Now that my contemporaries and those who followed us onto the playing fields of Yankton know more about his early life, I am confident they’ll feel even greater pride in recognition from this modest and decent man.

During NBC’s coverage of the fiftieth anniversary of D-Day, I was asked by Tim Russert on Meet the Press my thoughts on what we were witnessing. As I looked over the assembled crowd of veterans, which included everyone from Cabinet officers and captains of industry to retired schoolteachers and machinists, I said, “I think this is the greatest generation any society has ever produced.” I know that this was a bold statement and a sweeping judgment, but since then I have restated it on many occasions. While I am periodically challenged on this premise, I believe I have the facts on my side.

This book, I hope, will in some small way pay tribute to those men and women who have given us the lives we have today. It is not the defining history of their generation. Instead, I think of this as like a family portrait. Some of the names and faces you’ll recognize immediately. Others are more like your neighbors, the older couple who always fly the flag on the Fourth of July and Veterans Day and spend their vacation with friends they’ve had for fifty years at a reunion of his military outfit. They seem to have everything they need, but they still count their pennies as if the bottom may drop out tomorrow. Most of all, they love each other, love life and love their country, and they are not ashamed to say just that.

The sad reality is that they are dying at an ever faster pace. They’re in the mortality years now, in their seventies and eighties, and the Department of Veterans’ Affairs estimates that about thirty-two thousand World War II vets die every month. Not all of them were on the front lines, of course, or even in a critical rear-echelon position, but they were fused by a common mission and a common ethos.

I am in awe of them, and I feel privileged to have been a witness to their lives and their sacrifices. There were so many other people whose stories could have been in this book, who embodied the standards of greatness in the everyday that the people in this book represent, and that give this generation its special quality and distinction. As I came to know many of them, and their stories, I became more convinced of my judgment on that day marking the fiftieth anniversary of D-Day. This is the greatest generation any society has produced.