CHARLES O. VAN GORDER, MD

“If I had my life to do all over again, I’d do it the same way—go somewhere small where people have a need.”

IT IS NOT SURPRISING, I suppose, that the horrors of war give birth to a new generation of good Samaritans. Young men and women who have been so intensely exposed to such inhumanity often make a silent pledge that if they ever escape this dark world of death and injuries, this universe of cruelty, they will devote their lives to good works. Sometimes the pledge is a conscious thought. Sometimes it is a subconscious reaction to their experiences. This is the story of a good Samaritan who set out in life to heal, found his greatest personal and professional tests under fire, and returned home to his original calling with a renewed sense of mission.

There had never been a military operation remotely approaching the scale and the complexity of D-Day. It involved 176,000 troops, more than 12,000 airplanes, almost 10,000 ships, boats, landing craft, frigates, sloops, and other special combat vessels—all involved in a surprise attack on the heavily fortified north coast of France, to secure a beachhead in the heart of enemy-held territory so that the march to Germany and victory could begin. It was daring, risky, confusing, bloody, and ultimately glorious.

It will live forever as a stroke of enduring genius, a military maneuver that, even though it went awry and spilled ashore in chaos, succeeded. It was so risky that before he launched the invasion, gambling that the small break in the weather would hold, General Dwight Eisenhower personally wrote out a statement taking full responsibility for the failure if it occurred. He was grateful he never had to release it.

Dr. Charles Van Gorder, wartime portrait

A new generation of Americans has a greater appreciation of what was involved on D-Day as a result of Steven Spielberg’s stunning film Saving Private Ryan. For most younger Americans, D-Day has been a page or two in their history books, or some anniversary ceremony on television with a lot of white-haired men leaning into the winds coming off the English Channel as President Reagan or President Clinton praised their contributions. Saving Private Ryan, although a work of fiction, is true to the sound, the fury, the death, the terrible wounds of that day.

Charles O. Van Gorder was a special part of D-Day. He was a thirty-one-year-old captain in the U.S. Army Medical Corps in June 1944, a graduate of the University of Tennessee Medical School. He’d already served in North Africa when he volunteered to be part of a two-team surgical unit that would try something new for D-Day: it would be part of the 101st Airborne assault force, setting up medical facilities in the middle of the fighting instead of safely behind the Allied lines. They knew that casualties would be high and that saving lives would require immediate attention.

So Captain Van Gorder and his colleagues were loaded onto gliders for the flight across the English Channel and into Normandy. These were primitive aircraft, made of tubing, canvas, and plywood, with no engines, of course. They were silent—the element of surprise—and they could land in rough terrain.

Van Gorder remembers, “We landed in the field where we were supposed to, but they forgot one thing: when they put the brakes on, it made that glider just like an ice sled and it went zooming across the field. We hit a tree—which ended up right between the pilot and the copilot. Nobody in my glider was killed, but nearly all the other gliders had someone killed or injured.”

That was at four A.M. By nine that same day, June 6, 1944, Van Gorder and his fellow doctors had set up an operating facility, a precursor to the MASH units, the Mobile Army Surgical Hospitals that saved so many lives and, later on television, gave us so much intelligent entertainment.

They were located in a French château; they converted the milk storage room to an operating room, and by late that afternoon the château grounds were covered with hundreds of wounded young Americans. Van Gorder and the other surgeons operated around the clock for thirty-six hours, always wearing their helmets because the château was often in the line of fire. The Army had issued the medical team several cases of Scotch whiskey and Van Gorder later remembered, “The only thing that kept us going was sipping that Scotch. Finally, I got so tired my head fell down into an open abdomen.” He was ordered to go back to his tent for some rest. En route, a soldier offered him hot chocolate. When he decided to go back for the hot chocolate, a German bomb hit his tent, demolishing it. It was the first of many narrow escapes for Dr. Van, as he was called.

Altogether, it was a frantic and grisly scene that even now, more than fifty years later, Dr. Van Gorder cannot remove from his memory. “I have flashbacks every day,” he says. “All those boys being slaughtered, sometimes two hundred boys and only ten surgeons. The war made me a better doctor because I had to do all kinds of surgery. There were no trauma surgery books before the war to learn from.”

Van Gorder’s D-Day initiation wasn’t the end of his frontline experience; it was only the beginning. His unit stayed with the 101st over the next six months as it fought its way across Europe, headed for the heart of Germany. They were in the thick of the fighting during the long siege in Belgium, and during the Battle of the Bulge.

In December 1944, Dr. Van Gorder and his colleague and friend, Dr. John Rodda, were in the middle of surgery when their makeshift operating room came under heavy fire from German forces. “I was practically lying on my stomach operating on patients,” Van Gorder remembers, “because of the shooting coming right into the tent.

“I was the only one who spoke German, so I went to the end of the tent and waved a towel through the flap. I told the German commander we had more than fifty wounded, including German POWs. He told me to load them up. I had to leave one patient behind with his stomach open.” They were taken prisoner on December 19, 1944, Dr. Van Gorder’s thirty-second birthday.

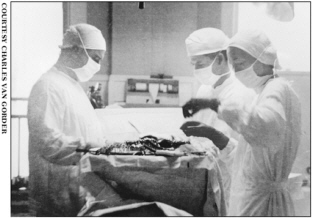

Dr. Charles Van Gorder in the Rodda–Van

Gorder Hospital and Clinic, Andrews, North Carolina

(left to right): Dr. Charles Van Gorder, Dr. John S. Rodda, nurse

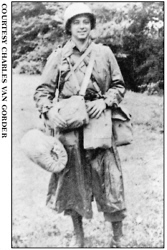

“Captain Charles Van Gorder demonstrates

what the well-dressed airborne surgeon wears on an

invasion,” June 13, 1944

Charles Van Gorder, MD, 1994

Van Gorder had suffered shrapnel wounds in his knees while the operating tent was under fire, so his friend Dr. Rodda supported him as they trekked through the snow under the watchful German guns. Van Gorder is convinced that without Rodda’s help the Germans would have shot him as a straggler.

He returned the favor when Rodda became ill. Two young American doctors, who had seen more death and suffering than most graduating classes of doctors were likely to see in a lifetime, were now trying just to keep each other alive. Nothing in medical school had prepared them for this primal struggle of being prisoners of war in a bleak winter landscape in the heart of enemy territory. Back home, their families had no idea of what they were going through, and it was just as well.

Van Gorder, Rodda, and the other prisoners were packed into boxcars, and the train moved them to the north of Germany, where they stayed on a siding for three days, locked inside. “Half of us would stand and half of us would sit in rotation because it was so crowded,” Van Gorder remembers.

Van Gorder got out of his confinement when the Germans needed a doctor to operate on a soldier needing an appendectomy. It was almost a fatal mission, however. American planes attacked the German train, not knowing there were Americans aboard. Van Gorder ducked beneath a car to avoid the heavy fire and then told the Germans, “I’m going to let the others out.” He risked his life to race into the line of fire and open the boxcar doors. The Americans poured out and immediately ran to a small hill and formed a human sign: USA POWS. The attacking American planes waggled their wings to indicate they understood, and broke off the attack.

The German army was fighting a losing battle, retreating deeper and deeper to the east, taking their prisoners with them. Van Gorder and Rodda were taken first to Poland and then to the Russian border. In the confusion, they escaped and started making their way back west, through Poland. Whenever they came upon a Polish hospital they’d stop to do what they could for the patients there, as most of the Polish doctors had been conscripted by the Germans. Finally they made their way back to American lines in the spring of 1945. Their war was over.

“When I was finally discharged, I had served five years in the war; I was overseas for thirty months straight,” Dr. Van Gorder says without a trace of bitterness. During that time his wife, Helen, a nurse from Nova Scotia he’d met in New Jersey during his residency before the war, gave birth to their first son, Rod. The infant died shortly after birth, a victim of sudden infant death syndrome. Dr. Van Gorder was in North Africa at the time, a long way from his wife’s side.

When the war was over, Dr. Van Gorder was headed for New York and a fellowship in reconstructive surgery. No doubt it would have been a high-income, prestigious practice. Before going to New York, however, Van Gorder visited his parents, who had relocated to the North Carolina mountain hamlet of Andrews. It’s tucked into the Smoky Mountains in that corner where North Carolina, Tennessee, and Georgia come together. It was a logging community, the very essence of backwoods.

After the turmoil of the war, however, it looked like a little piece of heaven to Dr. Van Gorder. The people were plain and friendly, the village was scenic and tranquil—and there were no doctors. It was the perfect match for a young physician who had experienced enough trauma, turmoil, and uncertainty in five years to last a lifetime. He decided to stay in Andrews and open a practice.

He called his wartime buddy and fellow surgeon John Rodda and invited him to become a partner. Dr. Rodda made one visit to Andrews and saw immediately what had attracted his friend. He agreed to sign on.

They opened a small clinic and mini-hospital above a department store. It consisted of an operating room, X-ray facilities, a blood lab, three examining rooms, and twenty-one beds. For the next ten years they were the only physicians in town. They really didn’t intend to stay forever but they quickly came to love their practices, their patients, and their adopted home.

Dr. Van Gorder’s son, Chuck, remembers his dad being very busy, and some evenings so exhausted he’d fall asleep at the dinner table. “When the clinic closed at five-thirty in the evening,” Chuck recalls, “my mother—who was the nurse—took the names of all the people who were too sick to come to town. We’d all get in the station wagon with our parents and they’d make their nightly rounds of house calls. They did this every night.

“I don’t think my dad ever left town the same time as Dr. Rodda. Andrews had a tough element and someone was always getting hurt in a fight or getting shot. Even so, some of the people in town at first didn’t trust Dad and Dr. Rodda because they were so young, and folks around here were used to older doctors. So Dad and Dr. Rodda brought in an older doctor from a nearby town to just be in the operating room when they did surgery. In return, they’d operate on that doctor’s patients without charging him.”

Chuck Van Gorder remains in awe of his father and what he meant to his neighbors. “Even after he retired,” he remembers, “people kept asking for him. A friend of mine was working for the power company when he blew his hands off in an accident. He was delirious. He kept screaming, ‘I want Dr. Van. Dr. Van will make this all right.’ ”

Other physicians returning from similar combat experiences made their contributions to postwar America in other ways. Dr. William McDermott—another combat surgeon who went ashore in Normandy and operated in frontline tents across France, at the Battle of the Bulge, and into Germany—was a product of Exeter, Harvard, and a one-year residency at Massachusetts General Hospital before the war. He says of his war experiences, “It was horrible, but the salvation was that you were doing something—you weren’t just sitting there and watching the horror. We were always so damn busy and so tired, but I got an enormous amount of experience. It was like running a full-time emergency room twenty-four hours a day.”

McDermott was involved in the liberation of one of the most notorious concentration camps, Ebensee. “You never in your life could imagine what it was like,” he says. “When I was treating kids in combat I didn’t have time to think, but the concentration camp was different. I went into a barracks and there were two men to every cot. They could barely move, but they got themselves up somehow and saluted me. I just about burst into tears. I stayed there for two weeks treating them, but two hundred died every day.”

It was an experience that stayed with Dr. McDermott when he returned to the Boston area and began a long, distinguished medical career at Massachusetts General Hospital, Yale, Harvard, and New England Deaconess Hospital. In his eighties, he remains the chairman of the department of surgery at Deaconess and he’s the Cheever Professor of Surgery Emeritus at Harvard Medical School, where he was on the faculty for many years.

Dr. McDermott has written several books, including a war memoir called A Surgeon in Combat, which recounts his experiences at Ebensee. That, in turn, led to a Boston meeting with a survivor of the camp, Morris Hollander, a Czech Jew. They may have met in the camp, although they couldn’t be sure. They did share the same lessons, however. One a Jewish inmate, the other a Roman Catholic doctor, they had both come to understand something about God and man in the barbarity of Ebensee.

In a Boston Globe account of their meeting, Dr. McDermott said, “God is a God of necessity. He sets the morals. If people break them, that’s their issue, not God’s.” Hollander responded, “Exactly. . . . Every nation has the ability to do as Germany did.”

Dr. McDermott says he remembers the horror of Ebensee to this day, but it remains for him primarily an intensely personal experience. “No,” he says, “I didn’t share this much with my medical students; I was a little restrained, but if the war came up during discussions, I would remind them of the levels to which humans can sink. It’s important for medical students to know those imperfections of the human race.”

He also isn’t interested in returning to Germany. On one occasion after the war, he had to change planes in the Frankfurt airport, and he got involved in a typical reservations foul-up. In exasperation he said, “Listen, fifteen years ago we had a helluva lot easier time taking Frankfurt than I’m having getting out of Frankfurt now.” Dr. McDermott remembers with a short laugh that he got a first-class ticket back to Boston almost immediately.

IN NORTH CAROLINA Dr. Van Gorder applied the lessons of his war experiences to his family of patients, and his philosophy was shared by his wife, Helen. After the death of their firstborn, Helen continued working as a nurse even as the family was wracked by the war. Her two brothers, Canadians, volunteered for the American forces and both were killed. Her husband was always in the thick of battle until he became a prisoner of war. Later the Van Gorders’son, Chuck, would be wounded in Vietnam while serving with his father’s old outfit, the 101st Airborne. When Chuck asked his mother how she managed all of that emotional turmoil she answered, “Since I was a little girl I’ve had trust in the Lord. I had faith it would all work out.”

It did work out for the Van Gorders because they did keep their faith in their God, in each other, and in the belief that life is about helping others. They passed that along to their two daughters and their surviving son. That’s another legacy of the World War II generation, the strong commitment to family values and community. They were mature beyond their years in their twenties, and when they married and began families it was not a matter of thinking “Well, let’s see how this works out . . .”

They applied the same values to their professional lives; they never stopped thinking about how they could improve health care for their community. While they were building their practice, Van Gorder and Rodda realized Andrews deserved more than their modest clinic, so they set out to build a hospital. Dr. Van Gorder became a regular visitor to the state capital in Raleigh, lobbying the governor to apply for federal Hill-Burton funds to build a hospital in Andrews. He succeeded. When the hospital was completed in 1956 it was a community triumph. Local residents working in the mills contributed through a payroll deduction program, sometimes as little as a nickel a week, or through bank contribution programs.

Today the hospital has sixty beds and a full range of medical services, from X rays to surgery. It is being expanded to accommodate sixteen more doctors, in a community that had none when the war ended.

As they steadily expanded the health care services available to the rural logging community, they kept up with the advances in medical technology and they were impressed with the progress in patient care. But Dr. Van Gorder laments the bureaucratic and commercial nature of modern medicine.

“The war taught me the importance of integrity in dealing with people,” he says. “I worked with some fine surgeons and we helped each other. Medicine was more altruistic. I just wanted to help people. Kids start out now thinking ‘How much money can I make?’ not ‘What can I do, how much can I help?’ ”

In the early days of his Andrews practice, his patients often paid with produce from their gardens or with freshly killed game. When that gave way to distant bureaucrats rejecting claims because a code was entered improperly or dictating care instructions, Dr. Van Gorder’s enthusiasm for what he loved began to fade. A man who began his medical career operating behind the lines and in the line of fire, a physician who learned more in a week of combat than an insurance clerk could know in a lifetime of paper shuffling, had little patience for the system that was overrunning his love of medicine.

In a small town, physicians are often more than the healers. They are the first citizens in every sense of the phrase. Dr. Van Gorder was a member of the Andrews board of education for twenty years; he was president of the Andrews Lions Club, and he was the grand potentate of the Shrine Temple in Charlotte, North Carolina. It was a life of service that hundreds of thousands of other World War II veterans were living in their hometowns across America.

In Dr. Van Gorder’s family, one daughter, Katherine, is a librarian in South Carolina; Suzanne is a nurse and a commander in the Naval Reserve in Florida; son Chuck, who when he returned from Vietnam worked for a time as a nurse, is in the real estate business near Andrews.

Van Gorder’s friend and partner, Dr. Rodda, died six years ago, and Van Gorder has been struggling with his own health problems—he suffered a small stroke in 1997—but he’s still cheerful and grateful for a full life.

His war experiences, however, now more than fifty years in his past, live on in his memory. “I have flashbacks of the war every day. You can’t get it out of your mind. D-Day, all those boys being slaughtered. When I was working in our hospital I thought about it a lot. I thought about how the war taught us to handle things. We learned a lot.

“The thing I am most proud of is that hospital,” he says. “If I had my life to do all over again, I’d do it the same way—go somewhere small where people have a need, contribute something to people who need it; help people.”