LLOYD KILMER

“My dad’s a piece of work. He’s the quintessential GI. What you see is what you get.”

NOTHING CAME TOO EASY for Lloyd Kilmer, the son of a Minnesota dairy farmer. When Lloyd was eight years old his father lost the farm to the bank and the family moved onto county assistance in the nearby small town of Stewartville. It was a common migration for farm families across the Midwest and it was a traumatic time in the lives of these proud, independent people.

Typically, everyone in the family went to work wherever they could. Young Lloyd sold newspapers, sacked groceries in the local market, and ran the projector at the movie theater. When he wanted to join the Boy Scouts, a county official lent him the fifty cents for the admission fee. He didn’t wear shoes in the summer so that he could have a decent pair in the winter.

He never had a bicycle as a kid, but it’s not a bitter memory. “That’s the way it was. There wasn’t much we could do about it.” What Kilmer remembers most about those years is that his father was humiliated when he had to apply to the WPA, the government relief program, for work so that he could feed his family. Kilmer says it left such a deep impression on him he made a pledge. “I never wanted to experience that sort of thing for my wife and family. I was driven toward never letting that happen.”

Goals in those difficult times were modest by modern standards.

Again and again I have heard from this generation, “We really didn’t have any expectations.” For too many of them, the idea of any real prosperity was simply too remote. Lloyd Kilmer was the first member of his family to graduate from high school, an achievement of considerable pride. He was working as a bellhop at a hotel in Rochester, Minnesota, home of the Mayo Clinic, when the war broke out.

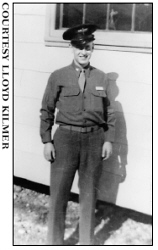

Kilmer, who had never been in an airplane in his life, knew immediately what he wanted to do. He wanted to become a combat pilot. He enlisted in the Army Air Corps on July 22, 1942, and was accepted for officer’s candidate school. Suddenly he went from being a bellhop in a comfortable hotel in a small, prosperous mid-western city to the rigors of pilot training in a succession of bases in Kansas, Oklahoma, and Texas.

Understandably, Kilmer is still very proud that he passed every test along the way and that within one year of the day that he first set foot in an airplane, he was a qualified pilot of a four-engine bomber, the B-24. His girlfriend pinned on him the silver wings and gold bar of a second lieutenant. In return, he gave her an engagement ring paid for by assigning to the jewelry store his ten-thousand-dollar military insurance policy. As he says, “My dreams had come true.”

He was assigned to the 448th Bomb Group, 712th Squadron, 2nd Air Division, 8th Air Force, based in England. He was flying combat missions on a regular basis, including D-Day, June 6, 1944. From the cockpit of his plane he could see the first wave of GIs going ashore on those murderous beaches. Kilmer says it is a day that “will live in my mind and heart forever.”

Twenty-three days later was another date fixed even more firmly in his memory. On June 29, 1944, his sixteenth mission, Kilmer was on a bombing run over a Nazi tank factory in Germany. He was taking heavy fire from antiaircraft guns on the ground.

“One shell went through the wing, rupturing the gas tanks, disabling an engine, and starting a fire. Another burst knocked the propeller off an engine. Other planes were exploding all around us. We could see parachutes coming out of some—and others with no parachutes. We were in big trouble.”

Still, Kilmer, who was just twenty-four years old, was confident they could make it back home or at least to the North Sea, where, if they ditched, they’d be picked up by an Allied sub or ship. “I didn’t have any real question,” he says. “I had a wonderful crew. They were superbly trained. There’s no doubt we could make it back. But it didn’t work out for us.”

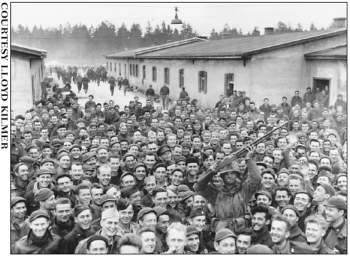

Liberation Day—Stalag 7A, April 29, 1945

Lloyd Kilmer, aviation cadet, 1943

Lloyd Kilmer’s plane, June 29, 1944, Beemster, Holland

They managed to put out the fires on the plane by going into a steep dive, but they were losing too much fuel to make it to safe territory. Kilmer was forced to crash-land in a potato field near Beemster, Holland. They all managed to survive the crash without serious injuries but the Germans had total control of the area, and within a short time Kilmer and his crew were all prisoners of war.

For the next ten months Kilmer was an inmate at two German POW camps. One interrogation was especially memorable for him. After days in solitary confinement, he was repeating only his name, rank, and serial number while being pressed at gunpoint for information about the 8th Air Force. Kilmer was taken to see a German officer.

Kilmer recalls, “The officer said to me, ‘Mr. Kilmer, you’ve been very stubborn. You haven’t told us what we want to know, so we’re going to tell you what we know about you.’ ” With that, Kilmer says, the officer pulled out a book describing the activities of Kilmer’s bomber squadron, its bombing reports, and biographies of the crews. Kilmer was stunned. Then the German officer said, “You think we’re pretty smart, don’t you? We know ninety-five percent of what’s going on in the American armed forces. However, your government knows ninety-seven percent of what’s going on in the German armed forces.”

That was the end of Kilmer’s solitary confinement and interrogation and it was the beginning of the long, cruel fight to survive, days of watching other inmates getting shot as they tried to escape, the same meals of watery cabbage or turnip soup, the cold nights with only a thin blanket for cover. When asked if he ever came close to just giving up the fight to live, Kilmer says, “Nope. I had a bride that I was going to marry. My mother and father, family, and great friends. No, I was going to go home.” Those same thoughts were in the minds of so many veterans I interviewed. In the worst of combat or other dangerous situations they were sure they were going to survive to return to the girl back home or to their families.

Kilmer was living in squalid conditions with 125,000 other prisoners at a German camp called Moosburg Stalag 7A in the spring of 1945. He had lost sixty pounds; his weight had dropped below one hundred. He was attending a POW church service on April 29 when the chaplain, a fellow American POW, paused to listen to the small-arms fire that had suddenly erupted around the camp and looked up to see low-flying aircraft. Kilmer chuckles as he remembers the chaplain saying, “Men, we’d better hit the deck.”

Not long after that, an American tank rolled through the German barbed wire. Lloyd Kilmer’s ordeal was over. To mark the liberation, the American rescuers went to a nearby church steeple where the Nazi swastika was prominently displayed on a flag. Kilmer says the men of Stalag 7A fell quiet as the swastika was lowered and an American flag was raised in its place. In a way he could not have fully appreciated at the time, that became a defining moment in Lloyd Kilmer’s life.

When Kilmer got back home he married Marie immediately and the Army arranged for medical and psychiatric treatment at a prisoner-of-war rehabilitation center in Miami Beach. He was eased back into a normal life in time to use the GI Bill and attend the fall term at Creighton University in Omaha in 1946. For a young man who was proud of his high school diploma just four years earlier, this was an unexpected opportunity.

He made the most of it, getting a degree in just three years while selling real estate part-time so successfully that, when he graduated, Omaha’s largest firm offered him a full-time job. Kilmer and Marie started a family. Their first son, Lloyd Jr., was born in 1950, and Frank followed four years later. Baby Boomers.

The boys remember Kilmer as a “God-and-country patriot,” a stern disciplinarian, and a driven businessman. Kilmer worked long hours in real estate and in a savings and loan company, where he became an officer. He was deeply involved with ex-POW organizations and the VFW. He was a scoutmaster for the local Boy Scout troop and active in his church. He organized a law-enforcement appreciation dinner during the sixties, when “law and order” were fighting words for a new generation.

For his sons, however, Kilmer was a distant figure. Lloyd Jr. and especially Frank had a difficult time relating to him. Lloyd Jr. says his father “always had a rigid set of ethics. He would say, ‘This is the way it’s going to be.’ Other parents threatened to send their kids to military school. My dad followed through.” Both boys went to Culver Military Academy in Indiana for a time, a point of pride for their father but far less so for them.

Frank and his father had some monumental arguments during the Vietnam War, when Frank dropped out of college. “It was a very difficult time in my family. And my father felt betrayed by his sons for not agreeing with his values and views about the war in Vietnam and about that era in general.”

Kilmer became such a well-known public figure in Omaha that he ran for county clerk and controller in Douglas County, and he won as a Republican at a time when the courthouse was a Democratic stronghold. But at home he was an intensely private man when it came to his past. He never talked to his sons about his war experiences. As Frank says, “His work habits and his devotion to work were typical of men of that generation who went through traumatic experience, and his relative emotional distance was also quite typical.”

The boys took their own paths in life. Lloyd Jr. recently received his PhD in education after a quarter century as a school principal. Lloyd Sr. was in the audience when his elder son received the degree. Frank left college and went into a Buddhist monastery for two years before becoming a plumber in California. Both have been married and divorced.

Their often strained relationship with their father was not unique for Baby Boomers, especially when their two worlds diverged so sharply during the sixties. The fathers were wholly unaccustomed to a permissive society. They were happy simply to be alive and, given all they had been through, they had this nagging fear it could all happen again. Their children came of age at a time when excess, not deprivation, was the rule, when their government lied about a new war, when the concepts of duty and honor were mocked.

Those were the two conflicting views of life and of the world in the Kilmer household. Now that both generations have aged and mellowed some, they’re slowly finding more common ground.

For Frank it began when his parents moved to Sun City West, a popular retirement community outside of Phoenix. His father noticed that the main boulevard had no flags displayed on the Fourth of July. Ever since that day, April 29, 1945, when the swastika went down and the American flag went up near his prisoner-of-war camp, Lloyd Kilmer has looked for the Stars and Stripes. He started a campaign to do something about R. H. Johnson Boulevard. “I devised a plan to attach an American flag to each of the hundred power poles along the boulevard,” Lloyd says. It’s now known as the Boulevard of Flags. Red, white, and blue American flags flutter every twenty yards or so along the thoroughfare that leads to the spacious retirement homes of so many World War II veterans.

They dedicated the Boulevard of Flags on Presidents Day 1989. Lloyd was honored for his role with the Patrick Henry Award for Patriotism, one of the highest awards of the American Legion.

Frank says of his dad, “He will brag about his involvement with the POWs and the VFW and the flag thing. But what I really appreciate about him is how he took care of my mother for ten years when she was really ill.”

Shortly after they retired in Arizona, Marie had a series of health problems—a broken hip, then a stroke followed by Alzheimer’s disease. The American dream for the Kilmers turned into a nightmare of emotional and physical pain. Lloyd never complained. He simply took care of the love of his life, hiring a nurse a few afternoons a week so he could go shopping. It went on for almost ten years before Marie died. Frank, who had continued following the Buddhist faith after his earlier feuds with his father, was deeply impressed and, for the first time, felt a real bond with him.

They grew even closer when Lloyd met a widow after Marie died. His new love, Ruth, had been married for half a century to another ex-POW. She was a former schoolteacher and the daughter of a small-town Iowa banker. It was a perfect match, but Frank remembers how his father was worried. “He needed affirmation it was okay,” Frank says. “What better person to get validation for something he perceived as unconventional than from his nonconformist son?”

Lloyd and Ruth are married and they think of their life in Sun City as paradise. Since her first husband was also a POW, Ruth knows never to serve anything containing turnips or cabbage. She also knows to say Lloyd’s name softly if she wants to awaken him from a nap; an unexpected touch or a loud “Wake up!” startles him still.

Lloyd remains active in the campaign to get a constitutional amendment to make it illegal to desecrate the flag, and he often attends reunions of his old bomber squadron held by the Ex-POW Association.

As his son Frank says, in a mixture of affection and admiration, “My dad’s a piece of work. He’s the quintessential GI. What you see is what you get.”