GORDON LARSEN

“I didn’t talk about the war much. I spent most of my time trying to forget it.”

FOR LLOYD KILMER, the war and his experience as a POW was a central theme throughout his life, even if he didn’t share that with his family. Other veterans shoved their war experiences to the far corners of their lives and sealed them off as best they could. They could never completely erase the memories or the residual effects of their training, but they were determined to start an entirely new life once the war ended.

In 1953, when I was living in a small town constructed by the Army Corps of Engineers along the Missouri River in South Dakota, I was surrounded by the young veterans of World War II who were busy making up for lost time: raising families, earning a living by building the large hydroelectric dam across the Missouri on this isolated stretch of the Great Plains, trying to forget what they had been through just a few years earlier.

As a talkative kid, friendly to grown-ups, I heard lots of stories about their days during the Depression or their long-ago sports achievements or hunting and fishing lore, but I cannot recall any of the veterans sitting around telling war stories. It just wasn’t done.

I do remember one startling comment, however. It came from Gordon Larsen, a popular member of the community. He was a stocky, cheerful young man who worked on a crew that kept the electrical, heating, and plumbing systems going in the town. He had such a lively sense of humor that it was almost worth it to have your furnace break down. Gordon always kept up a lively chatter while he worked on it.

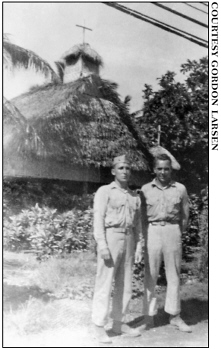

Gordon Larsen (right) at Guadalcanal, 1942

So it was surprising that the morning after Halloween he came into the post office, where my mother worked, and complained about the rowdiness of the high school teenagers the night before. My mother, trying to play to his good humor, said, “Oh, Gordon, what were you doing when you were seventeen?”

He looked at her for a moment and said, “I was landing on Guadalcanal.” Then he turned and left the post office.

It was a moment that made a deep impression on Mother. She shared it with me when she came home that evening, and we have talked about it often. It was so representative of how quickly times had changed for young people.

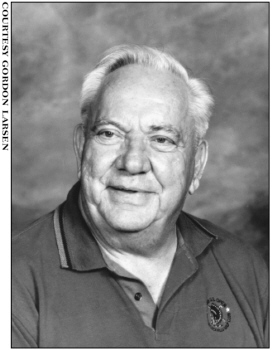

Gordon is now seventy-three. He’s retired from the Army Corps of Engineers after thirty-five years, having moved on from fixing furnaces to operating the sophisticated control systems in the powerhouses of dams in South Dakota, North Dakota, and Washington. He was surprised when I told him my mother and I remembered that moment in the post office. “I didn’t talk about the war much,” he said. “I spent most of my time trying to forget it.”

Gordon quit high school in Omaha to join the Marines in 1941, following the path of his older brother, Jim. He trained in San Diego with the 3rd Marine Division, 9th Regiment, and immediately shipped out for the Pacific, where he carried the heavy Browning automatic rifle ashore at Guadalcanal, Bougainville, Guam, and Okinawa, participating in some of the heaviest fighting of the war.

He hooked up with Jim, then nineteen, in the 3rd Marines, and they went ashore together at Bougainville. It was a bloody, unforgettable day for Gordon. His brother was hit almost instantly, severely wounded, on the beach. Gordon remembered it vividly. “He bounced around,” he said. “He was really hit.”

Jim was down in an exposed position, and every time a rescue effort was launched, the Japanese opened up. Gordon’s commander told him they couldn’t do anything until dark. Jim lay there all day, his life draining from him. Finally, once it was nighttime, they were able to get him back to their lines and transported to a waiting ship.

But too much damage had been done. Gordon’s brother died two weeks later in a Denver hospital.

As he told me this story, unprompted, on a telephone call across forty-five years, Gordon’s voice grew husky and more distant. “I haven’t”—he hesitated and then went on—“I haven’t talked about this hardly ever.”

He said he still has nightmares about his days in combat, and when I knew him, in the early fifties, when the memories were especially fresh, he said he thought about it all of the time, even when he was entertaining us while fixing our furnace.

There were no psychiatrists in our small community for him to see, even if he had been inclined, which he wasn’t. “I just wanted to forget,” he said, “I just wanted to get on with my life.” Gordon said that when he went into a bar in those days and heard guys talking about combat, it made him sick, so sick he’d just walk out rather than stick around and share the painful memories. Besides, he always figured those who were willing to talk about combat had never really experienced it.

After all the bloody fighting across the island chains leading to Japan, Gordon’s outfit was on Guam, preparing to board ships that would take them to the invasion of the mainland. Then word came of the surrender of the Japanese. Gordon’s shooting war was over.

He came home with his unit. There had been 240 men in it when he left San Diego three years earlier. Only eight returned alive and uninjured. Gordon says he’s never been in touch with any of them. He doesn’t want to revisit those days.

He does credit the Marines, however, and that awful experience during his formative years with giving direction to his life. He said he was a wild kid, and he didn’t know what would have happened without the discipline of the Marines and the sobering experiences of war.

He came home a man, went to school nights to get his high school diploma, and worked days learning the trade of a furnace-and-heating-system technician. “I was never out of work,” he proudly recalled. “I never had to take the 52–20 program”—a government subsidy for returning veterans who couldn’t get work—twenty dollars a week for fifty-two weeks.

Most returning veterans went to work or back to school as swiftly as possible. They were acutely aware of what they had lost in their training years. In fact many of them to this day just subtract three, four, or five years from their chronological age in good humor, laughingly explaining that those were the years they lost during the war.

Gordon Larsen

Gordon’s choice of furnace-and-heating work proved to be a good fit. It was a skill in demand, for America was in a building boom and home heating was changing over from coal to oil. After fixing furnaces on Army Corps of Engineers projects, he stepped up to powerhouse operator on the Corps’ big hydroelectric dams in the Midwest and West.

He met his wife, Emelia, on the job in Omaha and they raised six children, four boys and two girls. Gordon reveres his Marine Corps connection but he’s also grateful his sons never had to serve. As he said of his Marine days, “It was a million-dollar experience, but I wouldn’t give you a plugged nickel to go through it again.”

Part of that experience was learning the lessons of loyalty and family. As his Marine buddies had been his family in training and in combat, he carried that attitude into his civilian life. He said, “It’s hard to explain, but my friends are like my family. I found out in the Marines what that can mean in life, and I’m still that way today.”

Life didn’t always work out the way Gordon had hoped. When he already had six children of his own and was working two jobs to make ends meet, he took in a young Sioux Indian as a foster child. He just felt sorry for the tot, whose parents were both in jail. The boy lived with the Larsens for several years but grew increasingly difficult to control, at one point attempting to burn down their house. They were forced to send him back to the reservation and they’ve never heard from him since. This is not an unusual occurrence when white families try to raise young Indians. The cultural differences often become too great to be successfully managed, but Gordon still feels disappointed that it came to a bad end. It was not what he had learned in the Marine Corps, to lose a family member because there was no common ground.

When I talked to this ordinary man with such extraordinary experiences during his teenage years, I was sorry that he hadn’t shared them with the young people in our community during the fifties. I understood, of course, why he didn’t want to revisit those nightmare years, but I am confident we could have learned something from him.

World War II left another mark on Gordon Larsen—he’s an unabashed patriot. That’s a part of American life lost on younger generations, he believes. It’s a common refrain among World War II veterans, forged as they were on the anvil of military discipline and the call to duty to defend their country against real peril. “Whenever I hear Taps or see a flag go by, I get tears in my eyes. Even now,” he said, “and I’m seventy-three.”

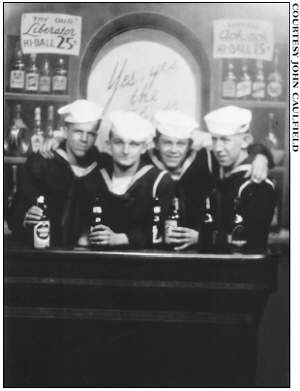

John Caulfield (far right) with buddies, Panama, 1945

The ROMEO Club—

Retired Old Men Eating Out