LEONARD “BUD” LOMELL

“We were trained so well I didn’t believe anything could kill us.”

LEONARD “BUD” LOMELL hasn’t been an active-duty U.S. Army Ranger in more than a half a century, but in his heart and in his mind he still wears the distinctive patch of the elite military unit that had the most dangerous assignment on D-Day. He led his men up the sheer cliffs at Pointe-du-Hoc while German forces dropped grenades on them, kept up a steady stream of fire, and even cut the ropes the Rangers were using to scale the precipice. We met when Lomell was one of the veterans featured in NBC News’s documentary on the fortieth anniversary of the invasion.

By then he was a sixty-four-year-old lawyer from Toms River, New Jersey, but as we rode together in a small motorized rubber raft just offshore from Pointe-du-Hoc, talking about that day decades earlier, I could almost see the tough, young First Sergeant Lomell directing his men as they landed under the withering fire of the German forces.

They had been getting ready for this mission for more than a year, undergoing training that was so grueling that many of the Rangers said they were looking forward to combat to escape the rigors of preparing for it. They had endured long speed marches with full packs, nighttime landing exercises in the cold waters of the Atlantic, hand-to-hand combat training, climbing slippery rock cliffs and rappelling down again. They were young men, between eighteen and twenty-four, and superb athletes, their bodies sinewy with muscle after months of the most demanding forms of physical exercise.

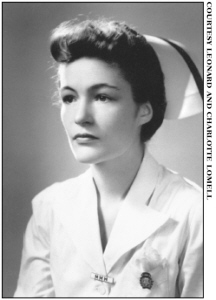

Leonard Lomell, wartime portrait

Charlotte Lomell

Bud Lomell had volunteered for the elite Ranger Corps after enlisting in the Army following college. He was the adopted son of Scandinavian immigrant parents who took him into their family when he was just an infant in Brooklyn. Later they moved to the Jersey shore, where Bud grew up, pampered by two older sisters and a big brother in the poor and hardworking family.

He remembers that the night he graduated from high school his father bought him some ice cream. As they sat at the family’s kitchen table, Bud was stunned when his dad burst into tears and said, “I am broke. I don’t have any money. I can’t help you go to college. I wish I could, but I can’t.” Bud had never seen his father cry. He recalls, “I went over to him, put my arms around him, and told him not to worry. I could make it on my own.”

Bud knew the family was poor. His dad was a housepainter, and at the height of the Depression no one in their working-class community was spending money to paint their home. Bud always had after-school and summer jobs to help pay the way, and he figured his athletic prowess would help him get a college education.

It did. He enrolled at Tennessee Wesleyan College on a combination athletic scholarship and work program, earning letters in football and participating in Golden Gloves boxing. He was also editor of the school newspaper and president of his fraternity before he graduated in 1941.

He returned to New Jersey, where he was able to get a job as a brakeman on a freight train, often working sixteen-hour shifts on the runs up and down the Atlantic seaboard. He knew, however, that before long he’d be in uniform, so he enlisted in the Army.

Three years later he was a first sergeant in charge of a platoon of Rangers as they ran their LCA ashore at the base of Pointe-du-Hoc. Lomell was commanding the platoon because his lieutenant had been reassigned just a few days before.

As they were landing, Lomell felt a sharp pain in his lower back. He was sure another Ranger with whom he had been arguing the day before had hit him. He turned and gave the guy a whack. Lomell still laughs when he recalls how the other Ranger was stunned, saying, “What’s that’s all about? I did nothing to you!” Lomell didn’t realize until later that, in fact, he’d been shot through the right side. He kept going despite the wound.

The 2nd Rangers had a specific mission on Pointe-du-Hoc. They were to knock out five 155mm German coastal guns Allied intelligence figured to be just atop the cliffs. When Lomell and his men got to the top, however, there were no major German guns on the emplacements. Lomell and another sergeant, Jack E. Kuhn, found a dirt road leading inland and they began to follow it.

By now their daring mission is well known to students of that chaotic and vitally important day. Stephen Ambrose and many others have recounted what the two sergeants accomplished. They found the five 155mm guns heavily camouflaged, well back from Pointe-du-Hoc and aimed at Utah Beach, another landing spot for the Allies on D-Day. The guns were not manned, but Lomell and Kuhn could see German troops about a hundred meters away, apparently forming up to get the guns operational.

Lomell instructed Kuhn to cover him, saying, “Give me your grenades. . . . I’m gonna fix ’em.” He ran to the guns and attached thermite grenades to critical parts and smashed the sights of all five guns with his rifle butt. The two sergeants withdrew to get more grenades and finished off the gun emplacement by disabling the remaining weapons. Mission accomplished.

It was just nine A.M. D-Day morning and Sergeants Lomell and Kuhn had already performed so heroically they would later be awarded the Distinguished Service Cross and Silver Star, respectively. It was also the beginning of a long war for both men, as they fought their way across Europe in all of the major campaigns, including the Battle of the Bulge.

That morning and in the days following the heavy fighting on and around Omaha Beach, First Sergeant Lomell came face-to-face with the worst of war. “When I saw my dead Ranger buddies laid out in rows,” he told me later, “their faces and uniforms caked with dirt and blood, I couldn’t believe it. I wanted to yell at them, ‘C’mon, get up!’ We were trained so well I didn’t believe anything could kill us.”

Before the war was over Lomell would be wounded twice more and would receive a battlefield promotion to second lieutenant. In 1945 he was ready to come home, and when he did, he led other uniformed veterans from his hometown in a victory parade down the main street of Point Pleasant, New Jersey.

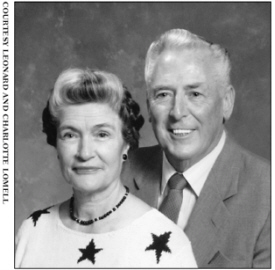

Charlotte and Leonard Lomell

Lomell family portrait, taken at the Lomells’ fiftieth wedding anniversary, June 6, 1996

He had not been home long when his mother began to talk to him about that nice girl he had been seeing before he enlisted, Charlotte Ewart. She had been training to be a nurse at a hospital in Long Branch, New Jersey, in the summer of 1941, right after Lomell’s college graduation. He was already working seven days and nights a week so there wasn’t much time for courting. When they were together, however, the mutual attraction was strong. Charlotte remembers, “I thought he was very handsome and very self-confident. That was important to me. He knew what he wanted.”

Before long, however, Lomell had enlisted in the Army and, typically for him, he then turned all his attention to his military training. He called Charlotte occasionally when he was home on leave but he didn’t write, and soon they drifted apart.

After the war, when he took his mother’s advice and called, Charlotte was enrolled in a public health nursing program at the College of Seton Hall. They arranged to have dinner and as Lomell says, “She was just the most impressive girl I had ever known. The rest didn’t have a chance. We just picked up where we left off.”

A year and a half later they were married, on June 6, 1946, two years to the day after Sergeant Lomell was fighting his way up the cliffs at Pointe-du-Hoc, a bullet wound in his side, determined to find and knock out a battery of German guns. As Charlotte says now, laughing, “Every wedding anniversary we share with the surviving Rangers, because it is also the anniversary of D-Day.”

The GI Bill was Lomell’s ticket to a career he could not have expected to have before the war. It allowed him to enroll in law school, at LaSalle University and Rutgers University. By 1951 he had passed the state bar exam and been admitted to the New Jersey bar.

The Lomells continued to make their home in southern New Jersey, and by 1957 Bud had founded his own law firm in the growing community of Toms River, about halfway between Philadelphia and New York. It quickly became one of the largest in Ocean County. As Bud likes to say, “I ran it with Ranger discipline.” As the father of three daughters he was especially sensitive to the idea of sexual harassment before it became a popular workplace issue. Over the years, “I had to fire a couple of young lawyers for violating the rules in that area,” he says. “Paid ’em off and got them out of there. I’m proud that my firm is known as the ‘league of nations.’ We’ve had several women and men of different ethnic backgrounds, sixteen lawyers in all and about thirty other employees.”

Charlotte and Bud were a team at home and in the law firm. She kept the books and looked after the maintenance in the law offices, and together they made family decisions. They were raising three daughters of their own when Charlotte’s sister died, leaving a teenage son and daughter. The Lomells simply brought them into their family as their own and sent all five children to college.

Through it all, Bud kept a close association with his Ranger buddies from the war. When they were younger, the Lomell daughters—Georgine, Pauline, and Renee—were so accustomed to Ranger veterans from Bud’s old outfit dropping by, they just considered them “uncles.” Renee—Bud and Charlotte’s youngest daughter—a schoolteacher, considers those visits to be an important part of her education. “You really didn’t see the military side,” she says. “It was just a bunch of good men from a variety of backgrounds who cared about each other a lot.”

They rarely talked about the worst of the war, she says. “They talked about the fun times during training or whatever, never about the fighting.”

Renee also remembers as a teenager in the sixties how her father adapted to the idea of young men with long hair and unusual wardrobes. “He worried a lot more about our safety than he did about the length of hair,” she says. He had essentially the same attitude toward the war in Vietnam. He supported it at the beginning, but when he saw it was poorly planned and executed, a terrible waste of young American lives, he turned against it.

Most of all, what the Lomell daughters remember is their parents as a perfect team. Bud, the energetic and outgoing lawyer with a soft touch for his daughters, always consulted Charlotte, who ran the family finances and preferred quiet evenings to large social gatherings. They were divided politically, Charlotte as a Democrat and Bud as a Republican, but that rarely caused any real rifts. “Our parents are a team,” one daughter said, “and they made the family a team.”

As a lawyer Bud did have certain rules to protect his feelings about his family. If he took on a divorce case he would never discuss it after three o’clock in the afternoon because he didn’t want to be upset by someone else’s family dispute when he went home to his own family. He often attended juvenile court on Fridays, and the girls remember that when he came home those nights his warnings about the dangers they could encounter took on new meaning.

Daughter Georgine is an Episcopal priest and chaplain at a long-term-care facility in Louisville, Kentucky. She says of her dad, “He walks his talk. He’s all about fairness and justice. When my sisters and I were teenagers we looked younger, so when we went to the movies we could have gotten in on the kids’ prices, but Dad would never do that. From him we learned how to be straight arrows.”

One of Bud’s protégés is Judge Robert Fall, who sits on the New Jersey state appellate court. Fall was in a local grammar school when Bud came to speak, and he made an indelible impression. Later, when Fall was in law school, Bud hired him, first as an intern and then as a member of the firm. “He was just the epitome of a leader in that firm,” Fall says. “The lines were drawn very clearly between right and wrong, and with Bud you just didn’t cross the line. I learned so much about integrity from him.”

Fall says Bud didn’t talk about his war experiences, but there were occasions when the old Ranger training spilled over into firm activities. “Every year we went as a firm—lawyers and spouses—to the Princeton–Rutgers football game,” the judge remembers, chuckling. “We’d have to meet at the offices at a fixed time, travel in a convoy of cars to the game, eat a tailgate lunch at a specific time, and meet for dinner at a fixed time and place later. Bud ran it all with military precision.”

As time went on, Bud Lomell became much better known in Toms River for his civic contributions than for his war record. He was a director of a local bank, president of the county bar association, a member of the local school board, president of the local philharmonic association, and, as a lawyer, always available to do pro bono work for local firemen, policemen, juveniles, and churches.

Judge Fall says that in his role on the bench, he thinks about Bud Lomell every day, and he is guided by the lessons he learned from him about right and wrong. Although Fall has known about Bud’s war record since he was a grade-school student, he remains in awe of the raw courage he demonstrated on D-Day and beyond. “You wonder,” Judge Fall asks, “could I reach down and do that? I guess I’ll never know.”

As for Bud, he still goes to his law offices a few times a week, even though he’s been retired since the mid-1980s. He’s survived two heart surgeries and he still has a military command style. As we were sitting in his comfortable waterfront home along the Jersey shore, preparing to do an interview on his reaction to the Steven Spielberg film Saving Private Ryan, a gardener started up a power mower outside. Bud turned to Charlotte and said firmly, “Tell that lawn mower to move out and come back later.”

Bud had been a special guest at the Hollywood premiere of Saving Private Ryan. He was impressed that Spielberg had been able to re-create the chaos and the bloody conditions of the D-Day landing so effectively, but he had lots of problems with the rest of the film. Tom Hanks as a Ranger captain, he said, “should never be walking around with his men, all talking loudly in broad daylight. That would only bring in German mortars.” Also, Bud noted that Hanks and his men were much older than the soldiers had actually been. “We were all eighteen or nineteen years old; I was one of the older ones at twenty-four,” he points out.

Bud Lomell is now in his late seventies and he counts his long, happy marriage to Charlotte and the lives of their three daughters as the most meaningful events in the lifetime that began in the poor, immigrant neighborhoods of Brooklyn and took him to the heights of military and professional success.

Charlotte and their daughters recognize that Bud will always have another family as well. The men of the 2nd Rangers who landed with him on D-Day and fought their way across those beaches and the rest of Europe, those who lived and those who died, are in Bud’s heart forever. Bud still leads Ranger tours back to those battlefields, but when they come to the American cemetery on the headland overlooking Omaha Beach in Normandy, he stays in the back of the bus. “To walk up to one of my Ranger graves there gets to me to the point I can’t do it anymore. I know he knows I’ve been by—so I’ll just go sit in the bus.”