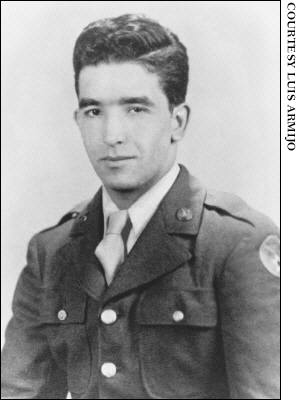

LUIS ARMIJO

“I live a good life. Not with riches or money. I love to teach. I love to help people.”

IN 1939, NEW YORK was the site of the World’s Fair, a glittering exposition in Queens, a half hour from midtown Manhattan, near where La Guardia Airport and Shea Stadium are now located. The theme was the future, and it was a dazzling exhibition of the fantastic possibilities about to be realized—including television, mass airline travel, and superhighways—spread out over 1,216 acres along a backwater of the East River. The industrial giants of the age, General Motors, Westinghouse, and General Electric, constructed elaborate exhibitions to demonstrate the possibilities of travel, electrical power, and communication. In his evocative book 1939: The Lost World of the Fair, David Gelernter makes the persuasive argument that the fair was a metaphor for a nation infused with the idea of a future full of grand possibilities. He wrote in his epilogue, “The future was a tangible, tasteable, nearly corporeal presence in your life.” For many Americans, precisely. Much of the country was living more in the past than in the future, however.

As a child in the forties I recall visiting farm families still living with kerosene lamps and outhouses. In our tiny home on the Army base the only heat came from a coal-burning stove in the front room. Many years later we went back to the now abandoned base with our children and my parents. My father found the foundation of our home and walked it off with our youngest daughter, Sarah. She was astonished to learn that her New York bedroom was larger than the small house that was home to five of us by war’s end. And, as my mother reminds me, we were living better than many families still struggling to escape the deprivations of the Great Depression and dealing with the acute housing shortage brought on by the war.

Luis Armijo, wartime portrait

In 1940 only about 54 percent of the homes in America had complete plumbing—running water, private bath, and flush toilet. Almost a quarter of the homes had no electrical power. Economists estimate that most American homes in 1940 had only 1,000 square feet of living space. In 1998, they estimate, new single-family homes have more than double that, a little more than 2,100 square feet of living space.

In the rural American Southwest in 1940 the past and the future were joined on the same desert landscape, rudimentary and surreal forces coexisting in the sagebrush and cactus. A new age of infinitely greater power and peril than anything history had known was about to begin in a remote corner of New Mexico—the development and the detonation of the first atomic bomb, the ultimate weapon of mass destruction. The manipulation of the atom was intended to produce nuclear power, first for war, then for peace, but always in reserve for war.

Not too far from where J. Robert Oppenheimer and America’s keenest scientific minds were racing to build and test a bomb so lethal not even they could imagine the full magnitude of its power, Luis Vittorio Armijo was growing up in the traditional fashion of his family. He was the son of a Spanish Basque father and an Apache mother. The family lived on a cattle ranch originally acquired by his Apache grandmother in a government land grant. It was located in the heart of the Apache reservation in southwestern New Mexico.

Armijo had an unusual childhood, even by the standards of that time and place. His parents and both sets of grandparents lived in the big house. The children—three boys and three girls—lived in a bunkhouse. Armijo recalls how the melding of the Apache and Basque cultures made it a lively household. “We spoke Spanish, French, and Apache,” he says. “We were self-sustaining—with the cattle herd and big gardens. We went to town only about once a month.”

Armijo didn’t get his first name until he was about ten years old because first he had to perform certain Apache rites. “Grandpa took me out to kill my first deer,” he says. “I had to drink some of the blood, then get the deer home, skin it, tan the hide, and make moccasins and other things.” A family friend suggested the name Luis and his grandmother said his middle name would be Vittorio, which Armijo was told was also the name used by Geronimo as a young man.

As a young man Luis spent a lot of time with his father, who, though Spanish, identified with his wife’s Apache ways. Luis remembers now, sixty years later, how his father taught him endurance. “He said, ‘If you can walk three miles, you can walk four.’ I learned how to track animals—how to tell a buck from a doe. I learned the medications from plants. White people take aspirin. We took the bark from the wala wala tree. I rode my horse three miles to the school bus and then took the bus ten more miles to school.

“I was just following the patterns of my parents. I thought I’d continue the same life. I knew nothing of the outside. On the maps in school, Colorado was in red and Arizona was in yellow, so I really thought when I got to those states they would be those colors. But when I got to high school and traveled with the basketball team to other towns, I realized I could do other things. I didn’t have to depend on the four winds like my grandfather—the ground that gives you nutrients, the air you breathe, the sky that goes from light to dark and back, and the rain.”

In 1942, his senior year in high school, Luis received his draft card and signed up for Army Air Force cadet training. A month later he was inducted and shipped to Fort Bliss, Texas, where he had an unexpected lesson in racial stereotyping. They said they wanted to use Southwestern Indians to speak their native language, as code talkers, to pass along vital military information.

“They called my name and I said, ‘I’m not a full-blooded Indian; I can talk the language but you can find better people—I’m supposed to be a pilot.’ The guy said to me, ‘Hey, Apaches don’t become pilots. They’re not smart enough.’ ” Armijo says people think that American Indians aren’t smart because they don’t talk a lot. But, he says, Indians are always thinking.

In the 1940s, Native Americans were an invisible population for most of the nation. It was thirty years before they began to demand—through AIM, the American Indian Movement—more autonomy from the federal government’s paternalistic system. When the war broke out, they were still largely confined to their reservations or the fringes of their native lands throughout the American West—but they were prepared to be warriors again. Moot Nelson, a Lakota Sioux, was working as a clerk in a western South Dakota draft board when the Japanese struck Pearl Harbor. Recalling the morning after, he said, “Here was a line of them already at eight A.M., Indian boys, twenty of them.” His supervisor told him, “Get ready, Moot, the boys are fighting mad.” That was true at reservations across the country.

Luis Armijo, wartime, in restored Japanese car

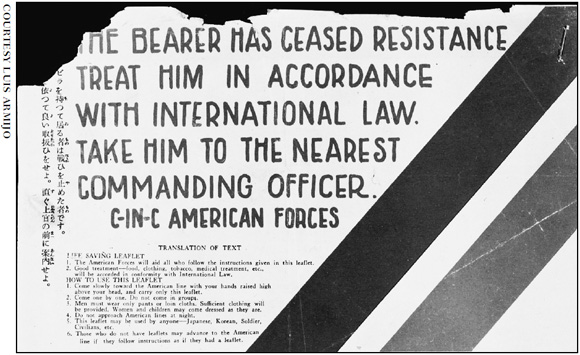

Life-saving leaflet dropped over Japan

In the Southwest, Armijo was sent to infantry basic training in California, but in the final week he heard about another test for the air cadet program and signed up again. He passed and was assigned to Truax Field, in Wisconsin, to train in ground communications. He wasn’t going to be a pilot, but he wasn’t disappointed. “I was just happy to be going places. I had never been on an elevator before, and here I had been in Texas, California, Wisconsin, and Illinois in a few months. I saw sailboats on a lake! I went to my first big basketball game. I couldn’t wait to go to the towns and see the people, the lawns, the churches. If I heard a siren, man, that was really something.”

At Chanute Field in Illinois, Armijo began an intense course in aviation electronics and communications. He learned navigation and, especially, how to guide a plane in when it was foggy. “We didn’t know it then,” he says, “but we were being trained to guide B-29s that would be landing on Pacific islands after bombing Japan.”

He became a member of General Curtis LeMay’s 20th Air Force, and early in 1945 he left San Francisco for a tiny island a little less than six hours by bomber from the heart of Japan. “We were a team of sixteen communications specialists. Our job was to tell the pilots how to land in the foggy conditions.”

As the summer wore on, Armijo and his friends began to suspect something big was up. A plane called the Enola Gay was practicing landings and takeoffs with two other planes following it. It finally took off with two other B-29s early in the morning of August 6, 1945, and arrived over Hiroshima at 31,600 feet at 8:15 A.M. Nuclear warfare was born in an enormous explosion that unleashed a towering mushroom cloud and triggered a firestorm that destroyed Japan’s eighth-largest city and killed more than eighty thousand of its residents. Back on Tinian Island, Armijo and his friends heard about the mission as Colonel Tibbets headed home. Armijo remembers, “As they were returning, the Enola Gay radioed it had been a success. Word quickly got around what they were talking about.”

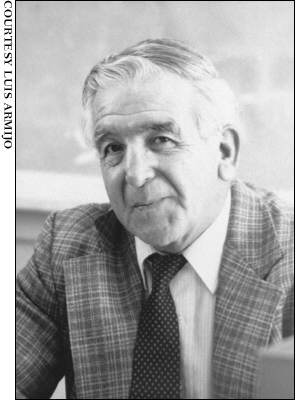

Luis Armijo

Luis Armijo, who three years earlier had been riding a horse to a school bus, was there for the beginning of this moment that, more than any other during the war, defined the perils of the future. He had no qualms about the attack on Japan, however, citing the ferocity with which Japan had waged war and the forecasts of hundreds of thousands of American dead, if not a million or more, if an invasion of the mainland became necessary.

For Armijo, the moment had a certain symmetry. His family was a little more than an hour’s drive north of the White Sands testing range where America’s newest weapons were exploded, some of them blowing out the windows in the family home.

About two weeks later a typhoon hit Tinian, taking Armijo’s tent and throwing him hard onto the ground. He cracked four vertebrae and had to be shipped home for treatment. The war was over, and Luis Armijo was eager to begin a new life.

Despite his service, however, when he returned it was “back to the same old thing.” Racism. “Before the war,” he says, “we were treated as bad as black southerners. We couldn’t have a business in town. The movie theater was segregated—minorities sat on one side, the whites on the other.

“During the war it was different. You signed papers and the Army didn’t say you were Hispanic or an Indian. The papers just said, ‘Hey, you’re an American soldier.’ If we got captured, we were just Americans. We were in a war.

“Once you got back,” he says, “you went back into the same old hole. I thought, ‘Hey, how can I make them understand me?’ ” A Veterans Administration counselor suggested a sitting job because of his back condition, so Armijo signed up for accounting courses at a New Mexico state teacher’s college. While there, the ways of his family awakened another interest: teaching. “Being the eldest in the family, whenever I learned something I was expected to teach my siblings. That was my grandfather’s way. So I got a degree in education with specialties in business and physical education.”

Armijo was hired immediately by the high school in Socorro, New Mexico, to teach typing, shorthand, business, and accounting. “I could see how eager these kids were to learn. To them, I knew more about the outside world than anyone. I said to them, ‘You don’t have to finish high school and go right back to the ranch. You can become a doctor, a nurse, a typist.’ ” That same message was heard in high schools across America. Returning veterans who went into the classroom brought a new worldliness and sense of adventure to the small-town kids they were standing before.

Armijo got a master’s degree and set out for California where, he heard, teaching jobs were plentiful. He was quickly hired at Fullerton Union High School in what was then rural Orange County, California. It was the beginning of a mutual love affair between teacher and kids.

“My philosophy,” he says, “is if you have a kid who leaves the house and comes to the school, that parent is saying, ‘Take care of my child as I would.’ I helped them make the right decisions. I kept money in my desk for those who didn’t have enough for lunch. They could just take their lunch money out of my petty cash and pay it back later. They didn’t have to leave their names. At the end of every year I always had more left over than what I started with. I made out a check to the company that provided the class rings. I wanted to be sure the kids who didn’t have the down payment at the time got to order theirs with everyone else. They always paid me back. You have to show them trust.”

The students, who liked Armijo, quickly came up with an affectionate twist on his name: Army Joe. They also knew that Army Joe didn’t miss much. If students were missing from class on a sunny day he’d drive to a popular beach and catch them there and administer a fatherly talk about the importance of education. He was a master at knowing when schoolyard fights were about to break out, and would step in at the last moment to offer mediation over Cokes or coffee. One time he forgot to duck, however, and one of two girls in a ferocious fistfight landed one on Army Joe—and he wound up with a black eye. Remarkably, one former student remembers, he didn’t lose his temper and the fighting coeds were filled with remorse.

A friend who has traveled with Armijo has been witness to his effect on his students. “Everywhere we’d go,” he says, “we’d run into one of his students. They’d run up to him, throw their arms around him, and say, ‘Mr. Armijo!’ And he always remembered them and told you all about them. It happened wherever we would go.”

There have been many changes in recent decades, however. “When I first started teaching,” Armijo says, “parents were behind you a hundred percent. When you called home they would take your advice. They’d come to school if there was a problem. When I was teaching you could always find one parent at home. Not anymore.”

Armijo likes the four-winds concept of his youth. He says a school has four sides: the students, the parents, the teachers, and the community. “And the parents are not holding up their part anymore. I think the home has gotten away from the parents.”

Armijo also thinks the new generation of teachers, however, has to share the blame. “When I retired in 1987 the superintendent said, ‘He always wore a coat and tie to school.’ Today’s teachers wear sports shirts. If their first class is at five past eight they arrive at eight. When I had an eight-thirty class I would be in the classroom at seven, opening the windows to get the air circulating, preparing the lessons. If you did an excellent job on a paper I’d make a small, complimentary remark, to be encouraging. Today so many teachers don’t take the time.”

Joe Yuddo remembers how Mr. Armijo, as he still calls him, always took the time. By his own description, Yuddo was a teenage rebel in the fifties, when he was a student in Armijo’s high school. Yuddo says, “I had a wonderful father, but in high school there’s always that conflict between parents and kids. Mr. Armijo was always the buffer that brought the kids back into line.”

Yuddo was seriously injured in a motorcycle accident as a teenager, and for nine months Armijo came to his home to keep him abreast of his Spanish studies. It was the beginning of a lifelong friendship. Yuddo says, “I lost both my parents, and Mr. Armijo is the closest thing I have to a mother and father.”

In his role as friend, Armijo takes a special interest in Yuddo’s son, who has cerebral palsy. Armijo accompanies the Yuddos to physical therapy, and lately he’s been helping them evaluate special-care facilities for the child in the event something happens to the parents. Yuddo says his counsel is always welcome because “sometimes you may not want to hear the truth, but you’re always going to hear it from Mr. Armijo.”

One of Armijo’s granddaughters, Shantelle Westbrook, has her own unique connection to his personal generosity. “I really needed money for college,” she says. Her father had abandoned the family so Shantelle went to her grandfather. He had a plan. He would begin selling Indian jewelry at swap meets on weekends. Shantelle was impressed. “He could have just retired, stayed inside, but instead he went out into the hot sun every Saturday to try to make money for my college fund.”

Armijo doesn’t see anything exceptional about his helping hand. “I buy from the various tribes,” he says, “and since I am part Indian I can get a license for resale. I go to the swap meets from six A.M. to five P.M. every Saturday and Sunday. I put the money in a bank account under her name. She’s starting her junior year in college and now I am doing the same thing for my younger granddaughter and grandson. I do it because I believe if you want to achieve a goal, you have to have an education.”

Armijo is a good Samaritan to those well beyond his circle of friends and his family. Once he retired from teaching, Armijo became an enthusiastic member of the local Lions Club. He immersed himself in the Lions’ many causes for the blind. “I collect glasses and turn them in. I organize drives to collect glasses. I organize raffles for the blind. We park a bus outside schools to screen kids for seeing problems. I’m in the bus, directing them to the different booths.” He was so dedicated and efficient in his work for the blind that Armijo won the Melvin Jones Award, the Lions’ highest honor, named after the club’s founder.

William Rosenberger, the Fullerton businessman who invited Armijo to join the Lions, said he did so only because his son pestered him so much. It turns out another member had considered inviting Armijo into the club, but he was afraid he couldn’t afford it on his schoolteacher’s salary. Rosenberger says, “The Lions almost missed a golden opportunity. He turned out to be a real asset.”

This humble man from another time and another place who went across the Pacific and was witness to the flight that changed warfare forever still rises every morning at five for a two-mile walk before attending Mass, every day, at a local church. Now in his late seventies, he says simply, “I live a good life. Not with riches or money. I love to teach. I love to help people.”

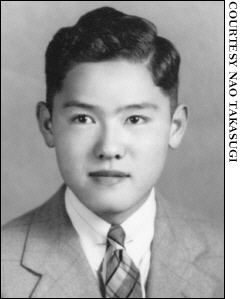

Nao Takasugi, June 1941

Norman Mineta